Safe or Scam? An Empirical Simulation Study on Trust Indicators in

Online Shopping

Sebastian Schrittwieser

1 a

, Andreas Ekelhart

2 b

, Esther Seidl

1 c

and Edgar Weippl

1 d

1

Research Group Security and Privacy, Faculty of Computer Science, University of Vienna, Austria

2

SBA Research, Vienna, Austria

Keywords:

e-Commerce, User Perception, Scam Shops, Trust Indicators.

Abstract:

Complaints from Internet users about online shopping scams have increased significantly in recent years.

An indication of the trustworthiness of a store can be obtained by a user on the basis of a number of trust

indicators, such as available payment methods or availability and correctness of contact information. In this

paper, we analyzed the behavior of 646 participants during online shopping with regards to non-technical trust

indicators. Our work is based on an online shopping simulation study including one trustworthy and two scam

store imitations. By automatically tracking the participants’ behavior, we found that only a minority of users

pay attention to trust indicators and most participants of the study purchased in an obvious scam store (28%)

– most likely due to its lower prices. Personal (age, gender, educational level, frequency of online purchase or

Internet usage at work) and contextual (time pressure) factors did not significantly influence the choice.

1 INTRODUCTION

Worldwide more than 5 billion people use the Inter-

net with numbers rising every year. At the same time,

it is estimated that up to 20% of all websites may

be fake and market forecasts predict that the finan-

cial cost of scam e-commerce will rise to $25 bil-

lion worldwide within the next years (Beltzung et al.,

2020). E-commerce scam in general means that crim-

inals use digital platforms to sell counterfeit products

or lure consumers into paying for services and goods

without receiving them. More specifically, scam on-

line stores (also known as fake stores or fraud online

stores) “involve scammers pretending to be legitimate

online sellers, either with a fake website or a fake ad

on a genuine retailer” (Competition and Commission,

2023). Preventing Internet users from falling victim

to fraud has become even more important with the in-

crease in online shopping due to the COVID-19 pan-

demic

1

.

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2115-2022

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3682-1364

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1072-2907

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0665-6126

1

https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/crime/300417542/

online-fraud-spikes-during-covid19-lockdown-buyers-

warned-of-social-media-scams

Our study targets these challenges by observing

user behavior with regard to trust indicators in an on-

line shopping simulation study. In the past, the term

trust indicators was used to describe warnings or sta-

tus indicators (e.g., the presentation of the validity of

HTTPS certificates in a web browser) (Cranor, 2006).

In our study, we define the term broader for all charac-

teristics of an online store that can give a customer an

indication of its trustworthiness. We examine to what

extend individuals pay attention to those trust indica-

tors to identify trustworthy (or scam) websites in their

online shopping experience and analyze factors pos-

sibly making individuals vulnerable to scam online

shopping (e.g., age, online purchase frequency). We

therefore aim to answer the following research ques-

tions:

• RQ1: Do people recognize and consider trust

indicators while shopping online and therefore

choose trustworthy online stores?

• RQ2: Which personal variables (e.g. age, on-

line purchase frequency) or context variables (e.g.

time pressure) influence the consideration of trust

indicators and the choice of online stores?

The main contributions in this paper can be sum-

marized as follows: (i) We provide an overview and

classification of properties typically present in scam

online stores. (ii) We implemented an online shop-

560

Schrittwieser, S., Ekelhart, A., Seidl, E. and Weippl, E.

Safe or Scam? An Empirical Simulation Study on Trust Indicators in Online Shopping.

DOI: 10.5220/0012852600003767

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Security and Cryptography (SECRYPT 2024), pages 560-567

ISBN: 978-989-758-709-2; ISSN: 2184-7711

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

ping simulation framework to study user behavior in

a naturalistic design. (iii) We conducted a study with

646 participants and present the results by describing

user variables as well as context variables.

2 RELATED WORK

Studies on User Shopping Behavior and Risks.

Previous studies examining online shopping behavior

have mainly focused on the relationship between per-

ceived risk and user behavior. In general, perceived

risk in online shopping was shown to negatively in-

fluence the intention to purchase products online (Al-

mousa, 2011). Other studies found that increased

trust can reduce perceived risk (Ganguly et al., 2010).

Egelman et al. conducted a laboratory study in

which they presented privacy information at alternat-

ing places and times and found that these influenced

the subjects’ purchase decisions significantly (Egel-

man et al., 2009). Also, increased trust will result

in increases purchase intention (Ganguly et al., 2010;

Hao Suan Samuel et al., 2015), as well as it increases

loyalty (

¨

Ozg

¨

uven, 2011). In turn, trust has been

shown to be influenced by security measures provided

by online shopping websites (

¨

Ozg

¨

uven, 2011). In

addition, in 2005 Rattanawicha and Esichaikul (Rat-

tanawicha and Esichaikul, 2005) identified factors

that are mandatory for an online store to be evaluated

as trustworthy by users. Another study conducted in

Austria examining characteristics of victims of scam

stores found men, individuals with higher educational

level, as well as individuals who are more willing to

take a risk are more prone to be victims of online scam

stores (Georgiev, 2021). In 2019, Frik et al. (Frik

and Mittone, 2019) conducted an online survey of 117

participants and concluded that security, privacy, and

reputation have strong effects on perceived trustwor-

thiness of stores while the quality of the website of an

online store plays a minor role only.

3 MATERIALS AND METHODS

The main goal of our study is to investigate if online

shopping customers recognize signs of online shop-

ping scam and if it influences their buying behav-

ior. In this section, we present a short background

on scam features, the study design, its procedure, and

recruitment of participants.

3.1 Online Scam Features

In the past a large number of features of websites

were identified which can be used to detect scam

stores (Carpineto and Romano, 2017; Wadleigh et

al., 2015). These can be roughly divided into two

categories. On the one hand, there are features that

are easily recognizable for end users such as avail-

able payment methods, standard information (im-

print, shipping information, etc.), and trustmarks from

independent issuers.

In contrast to these features, which can be evalu-

ated by end users without additional technical knowl-

edge or tools, there are also more opaque features.

These types of features include website hosting loca-

tion, age of the domain, and if the domain is in the

Alexa Top 1M/100K list.

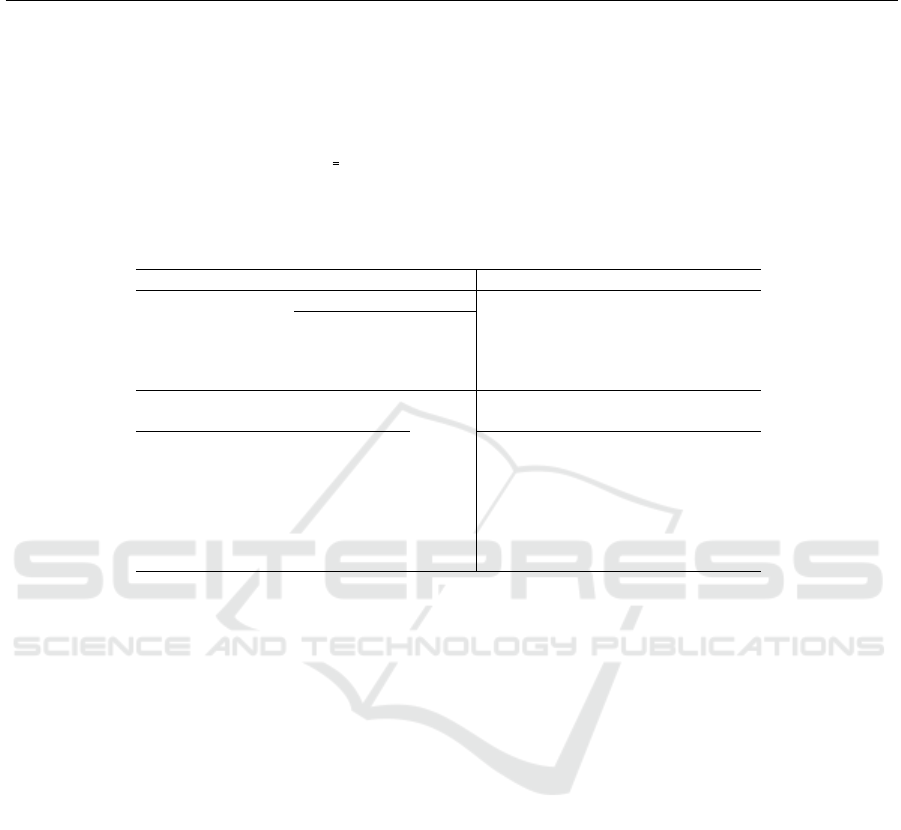

For our study, we aggregated all features of the

first category (user facing properties) from past liter-

ature and then removed those for which a possible in-

teraction of the user cannot be captured by our track-

ing (see Table 1). This primarily concerns browser

features outside of the actual web page such as view-

ing details on HTTPS certificates or the title of a web

page which is displayed in the tab or title bar of the

browser.

3.2 Study Design and Procedure

To capture a broad sample an online study design was

used with a cross sectional combination of observa-

tional and survey design to assess quantitative obser-

vational data (Barker et al., 2015), as well as a survey

to assess sociodemographic data and subjective expe-

rience of the participants regarding factors influencing

their online store choice at the end of the study.

3.2.1 Simulation Study

When studying human behavior there needs to be a

trade off between 1) a laboratory setting with little

experimental noise and 2) a design in the natural en-

vironment of participants, bearing the chance of high

experimental noise which makes it more challenging

to draw clear conclusions (Farnsworth, 2019). One

possible compromise between noise and an environ-

ment that feels natural to the participants are simula-

tion studies (Farnsworth, 2019). Observational meth-

ods are beneficial for assessing human behavior as

they can represent real behavior in the situation when

it occurs. Furthermore, observational assessments

have greater reliability and objectivity (Gesellschaft,

2023). In the present study we therefore opted for

a simulation to examine user behavior and further

implemented a naturalistic study design to increase

Safe or Scam? An Empirical Simulation Study on Trust Indicators in Online Shopping

561

ecological validity. Naturalistic designs are used to

mimic real-life as closely as possible, therefore being

characterized by a minimum of lifestyle rules for par-

ticipants and no interference of the investigators with

participants’ activities (Verster et al., 2019). We fol-

lowed the principles suggested when studying secu-

rity and privacy with regard to user behavior (Krol et

al., 2016). However, due to ethical concerns we did

not let participants pay with their money to purchase a

product, instead we provided fake payment informa-

tion for each participant.

For the observational part we implemented three

different versions of an online store, only varying

in their trust indicators (one “trustworthy store”, one

“veiled scam store” and one “obvious scam store”;

see Table 1). The implemented trust indicators in

the three online stores were selected based on an ini-

tial list derived from literature, followed by a discus-

sion and selection process with stakeholders (orga-

nizations dealing with e-commerce, including scam

stores) considering relevance and practicability. In

addition, we varied minor visual aspects of the dif-

ferent online stores (e.g., banner images, footer style,

and color) to make them more distinct for the partici-

pants and to make the changes in trust indicators less

obvious. Invited participants first visited the study

landing page including a description of the study pur-

pose, privacy statement, and the task they had to per-

form, namely to buy a backpack in any of the three

available stores for an upcoming trip. For each partic-

ipant we randomly selected if the instruction text in-

cluded time pressure or not. The time pressure manip-

ulation was implemented by informing participants

that they only have limited time to purchase the prod-

uct and that a hidden timer is running which would

end the study. However, no timer was implemented in

the study, the instruction was only formulated to in-

crease time pressure for the participants. Participants

were informed that the study investigates their online

shopping behavior, without naming online shopping

scam/trust as the primary focus of the study. This pro-

cedure was chosen to prevent participants from being

primed about the trust indicators of the study. Partic-

ipants were instructed to use their desktop computer

rather than their mobile phone or tablet to minimize

contextual factors impacting data quality.

Participants navigated through the online stores at

their own discretion. Nine different products (back-

packs) with picture, name and price were shown on

each shop’s main page.

For each product a details page existed, compris-

ing two or three pictures of the backpack, a short

product description, and stock/delivery time. In the

footer of each store, links to various subpages such

as the imprint and the terms and conditions, trust-

marks (one e-commerce trustmark and one trustmark

by a technical inspection agency) and payment logos

were presented. After participants added a product to

the basket and started the checkout process, a page

summarized the products in the basket and the total

sum of their order. On the next page participants had

to choose between different payment methods before

being redirected to a page presenting pre-filled fictive

shipping and billing address as well as payment infor-

mation. Upon confirming their simulated order and

payment, they were redirected to the survey page de-

scribed in the following section.

3.2.2 Survey

Immediately after the final order confirmation, par-

ticipants were asked to fill in a survey collecting

sociodemographic information (gender, age, educa-

tional level, profession) and behavioral variables (fre-

quency of private Internet usage and Internet usage

at work, purchase behavior, frequency of online pur-

chase). Furthermore, participants were asked to an-

swer if they felt time pressure during the task and if

it had an impact on their purchase behavior, as well

as to rate several impact factors (price, website de-

sign, name of the online store, product design, prod-

uct description, banner, payment methods, subjective

experienced seriousness of the website, general terms

and conditions, cancellation terms, shipping terms,

imprint, trustmarks) on their purchase decision on a

Likert scale of one (no impact) to five (big impact).

All items within the survey were mandatory.

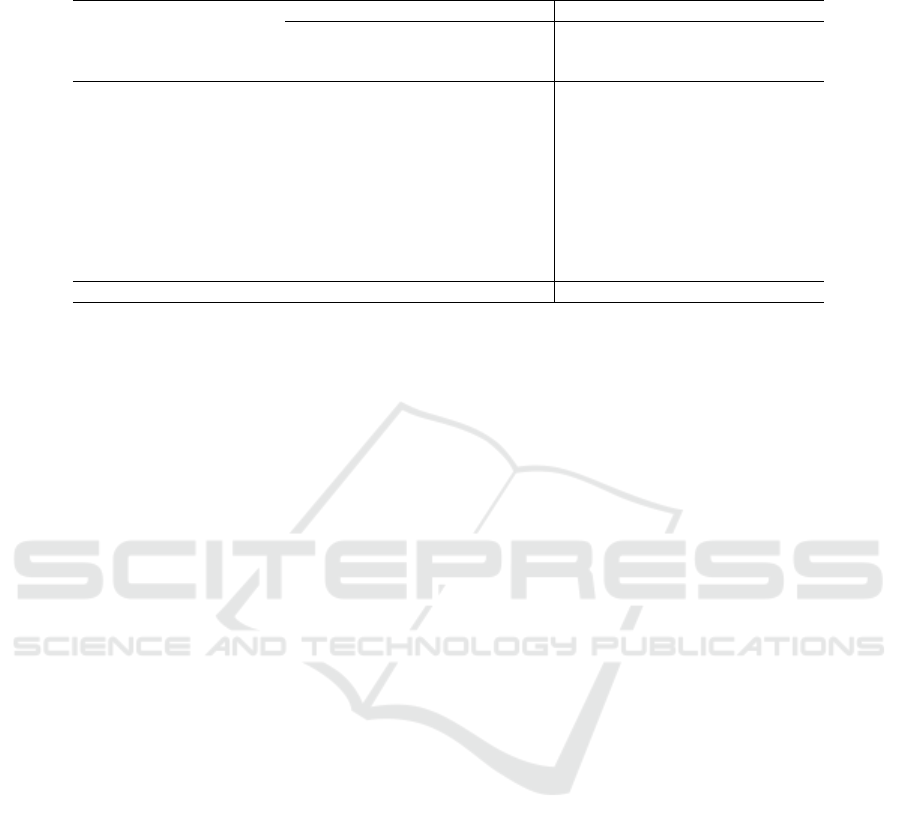

3.3 Recruitment and Sample

To recruit participants, companies and institutions in

Austria were contacted via email including the study

link and a short description. German-speaking partic-

ipants with and without experience in online shopping

above the age of 18 were included. Sample character-

istics can be found in Table 2.

3.4 Data Analysis

All analyses were run with Stata 14.2. For as-

sociations between variables we used Chi-squared

test, Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Kruskal–Wallis one-

way analysis of variance, regression analysis or analy-

sis of variances (ANOVA) depending on their level of

measurement and the number of group comparisons.

We accept a 5% type 1 error rate for each single test as

a feature of our study. Of 651 participants who com-

pleted the study, five had to be excluded due to ques-

tionable validity of the data (e.g., started in one store

SECRYPT 2024 - 21st International Conference on Security and Cryptography

562

Table 1: Online shopping scam features used in our study.

Security Feature Trustworthy shop Veiled scam shop Obvious scam shop

Online store title Taschenstore Rucksack-welt Sportverein-Bergnatur

Online store title (translation) bag store backpack-world sports-club mountain nature

Imprint complete and correct incorrect/incomplete none, contact form instead

General terms and conditions complete and correct incorrect return information error code

Trustmarks real trustmark logo of trustmark none

Payment options credit card (selected), prepayment, invoice prepayment (selected), error otherwise credit card

Return information voluntary for 30 days 14 days no information

Warranty information complete and correct complete and correct no information

Shipping free from 70 C, 3-5 days no shipping costs, 1-3 days product in stock info

European Union Cookie Banner yes no no

Spelling correct correct spelling & special characters errors

Table 2: Sociodemographic and behavioral sample description.

Age and gender Internet use at work n %

male female diverse

18-29 27 77 1 Daily 490 75.85

30-44 87 106 1 Several times per week 102 15.79

45-54 92 86 0 About once a week 18 2.79

55+ 95 74 0 Less than once per week 36 5.57

Educational level n % Online purchase frequency n %

No high school diploma 162 25.08 Weekly 62 9.60

High school diploma 194 30.03 1x/2 weeks 134 20.74

Academics 235 36.38 1x/ month 196 30.34

Other 55 8.51 1x/every two months 139 21.55

1x/ every six months 68 10.53

Less than every six months 41 6.35

Never 6 0.93

and continued two days later in another store, exces-

sive long pause within the study participation, switch

of store after a longer pause of inactivity). There-

fore, the final sample consisted of 646 participants.

For analyses including sociodemographic and behav-

ioral variables, we decided to include age, gender, ed-

ucational level, frequency of online purchase and fre-

quency of Internet usage at work. We did not include

the other assessed variables (profession, purchase be-

havior, frequency of private Internet use), as they cor-

relate with some of the selected factors and therefore

would not reveal additional results.

4 RESULTS

In the following we will describe the results of our

study with regards to the research questions. An in-

terpretation of the presented results can be found in

the discussion section.

4.1 User Behavior

We found that the obvious scam store was visited

most frequently (n=503), followed by the veiled scam

store (n=479) and last the trustworthy store (n=471).

Also the number of participants buying were high-

est in the obvious scam store (n=318), followed by

the trustworthy (n=178) and the veiled scam store

(n=149). Most participants visited all three stores

(n=385), but also a high amount of participants vis-

ited only one store without comparing it to the oth-

ers (n=224). Participants visiting two stores were rare

(n=37).

Amount of Trust-Related Actions. Participants

who bought in the trustworthy online store were found

to show about six more trust-related actions com-

pared to participants who bought in the obvious scam

store (b=6.41, p<.001), and four more trust-related

actions compared to individuals completing in the

veiled scam store (b=4.04, p<.001). Individuals com-

pleting in the veiled scam store were shown to execute

two more trust-related actions compared to obvious

scam store buyers (b=2.37, p<.001). Furthermore,

in the group of participants visiting only one store,

only a small number of individuals executed trust-

related actions, compared to the number of partici-

pants executing trust-related actions in the group of

participants visiting two or three stores (see Table 3).

Also, a very low number of participants payed atten-

tion to trustmarks (n=118) or clicked to check them

Safe or Scam? An Empirical Simulation Study on Trust Indicators in Online Shopping

563

(n=36). However, those who did bought most often in

the trustworthy online store.

4.1.1 Associations of User Behavior and Time

Pressure

Individuals within the time pressure condition re-

ported significant more subjective time pressure

(b=0.26, p<.001) and spent about 1.5 minutes less

in the study (b=-89.13, p<.001) compared to partic-

ipants in the non-time pressure condition. In gen-

eral, participants spent about 310 seconds (median;

= 5.2 minutes) in the study but showed a big varia-

tion in their duration (25 seconds up to 3110 seconds

= 51.8 minutes). Participants in the no-time pres-

sure condition executed two more trust-related actions

compared to participants in the time pressure condi-

tion (b=2.08, p<.001). However, no significant as-

sociation was found between the condition with and

without time pressure and choice of the online store

(d=0.06, p=.400).

4.1.2 Associations of User Behavior and

Behavioral Variables

Frequency of Internet usage at work, as well as the

frequency of online purchase did not show to have

a significant impact, neither on the amount of trust-

related actions (Internet usage at work: χ²(1)=1.72,

p=.189; online purchase frequency: χ²(6)=6.72,

p=.348), nor on the choice of the online store (Internet

usage at work: χ²(1)=3.606, p=.058; online purchase

frequency: χ²(6)=3.425, p=0.754).

4.1.3 Associations of User Behavior and

Sociodemographic Variables

The amount of trust-related actions was significantly

different between individuals with different educa-

tional levels, with academics showing the most and

participants without high school diploma showing

the least amount of trust-related actions (χ²(3)=13.93,

p=.003). However, no significant difference was

found between individuals with different educational

level and their choice of the online store in which

they bought (χ²(3)=2.22, p=.528) or the interaction

of educational level x amount of trust-related action

on the choice of the online store (F(49,559)=0.81,

p=.821).

Gender-Specific Analyses. For gender-specific

analyses participants with diverse gender were

excluded (n=2)

2

resulting in a sample of n=644 for

the following findings. In male participants, results

2

No analysis possible with n=2

were similar to the total sample, with most visits

in the obvious scam store (n=240; 80%), followed

by the veiled scam store (n=218; 72%) and last

the trustworthy store (n=193; 64%). In contrast, in

female participants, the trustworthy store was visited

most frequently (n=277; 81%)), followed by the

obvious scam store (n=262; 76%) and the veiled

scam store (n=259; 76%). However, the number of

participants buying in the obvious scam store were

highest in male (n=155; 51%) and female (n=162;

47%) participants. While male participants bought

least often in the trustworthy store (n=70; 23%; veiled

scam shop: n=76, 25%), female participants bought

more frequently in the trustworthy store compared

to the veiled scam store (n=108, 31%; veiled scam

shop: n=72, 20%). Amount of trust-related actions

were similar in both genders in the two scam stores

(male: veiled scam store n=2.672; obvious scam store

n=2.567; female: veiled scam store n=2.731; obvious

scam store n=2.639) and way less pronounced in the

trustworthy store (male: n=1.686; female: n=2.384).

No significant difference regarding the number

of trust-related actions was found between male and

female participants (d=0.13, p=.174;). We did find a

significant difference in the choice of the online store,

with female participants showing to have a decreased

risk to buy in the fake stores compared to the risk

of buying in the trustworthy store (trustworthy store

versus veiled scam shop: RRR=0.61, p=.030; trust-

worthy store versus obvious scam shop: RRR=0.68,

p=.041). A significant difference was found for

educational level between the gender groups (d=-

0.31, p<.001; female participants showing higher

educational levels), but no significant effect was

found for gender when considering educational level

on the choice of the online store (F(3,635)=0.14,

p=.938).

Age-Specific Analyses. Looking at different

age categories, we found that in all categories partic-

ipants most often bought in the obvious scam store

(18-29: n=49, 47%; 30-44: n=92, 47%; 45-54: n=89,

50%; 55+: n=88, 53%) and except for the youngest

age group, least often in the veiled scam store (18-29:

n=34, 32%; 30-44: n=43, 22%; 45-54: n=40, 22%;

55+: n=32, 19%). The youngest age group bought

least often in the trustworthy store (18-29: n=22,

21%). The lowest number of trust-related actions

was executed in the trustworthy store by all groups

(18-29: n=624; 30-44: n=1.195; 45-54: n=1.174;

55+: n=1.079), and with exception for the group

of the 30-44 year old participants followed by the

obvious scam store (18-29: n=802; 30-44: n=1.604;

45-54: n=1.412; 55+: n=1.397). Details on the

SECRYPT 2024 - 21st International Conference on Security and Cryptography

564

Table 3: Number of participants executing trust-related actions and number of participants who bought in stores by individuals

who visited only one store versus participants who visited two or three stores.

Visited one online shop Visited two or three online stores

Trustworthy

shop

Veiled

scam shop

Obvious

scam shop

Trustworthy

shop

Veiled

scam shop

Obvious

scam shop

n % n % n % n % n % n %

General terms and conditions 6 3 5 2 3 1 48 12 40 10 55 13

Impress / Contact 3 1 1 0 5 2 90 22 79 19 104 25

Shipping terms 4 2 2 1 3 1 50 12 66 16 73 18

Cancellation terms 4 2 1 0 4 2 54 13 68 16 78 19

Data security 4 2 4 2 - - 20 5 18 4 - -

Help / FAQ 1 0 0 0 2 1 15 4 22 5 44 11

mouseover trustmark (e-com) 5 2 5 2 - - 81 20 80 19 - -

click on trustmark (e-com) 0 0 0 0 - - 29 7 22 5 - -

mouseover trustmark (tech. insp.) - - 4 2 - - - - 89 22 - -

click on trustmark (tech. insp.) - - 0 0 - - - - 18 4 - -

n of participants bought in store 68 30 65 29 91 40 110 26 84 20 227 54

amount of individuals executing trust-related actions

by age category are presented in Table 4.

We did not find a significant difference between

the age categories with regard to the number of trust-

related actions (p=.838; χ²(3)=0.849) or the choice of

the online stores (p=.896; χ²(3)=0.60).

4.1.4 Ratings of Trust Indicators

Participants who performed trust-related actions rated

the indicators to have significantly more impact on

their purchase decision than those who did not per-

form the respective trust-related action (trustmark:

b=0.73, p<.001; imprint: b=2.04, p<.001; gen-

eral terms and conditions: b=1.05, p<.001; shipping

terms: b=0.43, p<.001; cancellation terms: b=0.82,

p<.001). However, ratings in the not-executing group

were still quite high for the different trust indicators

(between 2.2 and 3.6 on a scale of 1-5).

5 DISCUSSION

In our study we found that participants visited and

bought most often in the obvious scam store. Fur-

thermore, participants who bought in the trustworthy

store showed more trust-related actions compared to

those who bought in scam stores. Those who bought

in the obvious scam store executed the least trust-

related actions. In addition, about one third of the

sample visited only one online store and did not com-

pare different store versions. These results cannot be

explained by the order in which the online stores were

presented on the landing page of the study as the pre-

sentation was randomized for each participant. A pos-

sible explanation for the higher number of visits of the

obvious scam store could be provided by the pictures

and names of the stores, which might be most attrac-

tive for the obvious scam store. Also, the high visitor

rate of the obvious scam store impacts the number of

purchases in this store. Finally, the low pricing in the

obvious scam store seems to be a major reason for

participants to decide to buy in this store.

The least trust-related actions were executed in the

trustworthy store. It has been shown that in the group

of participants visiting only one store only a small

number of participants executed trust-related actions.

However, all groups showed highest purchasing rates

in the obvious scam store, with even higher numbers

in the group of participants visiting two or three stores

(54% versus 40%). Looking at the mouse activity we

found, that a very low number of participants tend to

check the authenticity of trustmarks by clicking the

displayed trustmark icons. Those who did click on

trustmark icons most often bought in the trustwor-

thy store and bought least often in the obvious scam

store. This might suggest, that those who are aware

of trustmarks and how to check them are able to dis-

tinguish between trustworthy and scam stores. How-

ever, with the small number of participants checking

for trustmarks this has to be interpreted carefully. We

also found that participants who did not execute trust-

related actions, rated the impact of the trust-indicators

quite high (between 2.2-3.6 on a scale of 1 to 5). This

might indicate, that participants are aware of possible

trust indicators for (non-)trustworthy stores, however,

they fail to transform this knowledge into actions.

Furthermore, analyses of variables possibly identify-

ing individuals at risk, namely gender, age, frequency

of Internet use at work, and frequency of online pur-

chase did not show significant effects with regards

to the amount of trust-related actions. There was a

significant effect of educational level on the number

of trust-related actions, this association, however, did

not show to have an effect on the choice of the online

store in which participants bought the product. Also,

Safe or Scam? An Empirical Simulation Study on Trust Indicators in Online Shopping

565

Table 4: Numbers of participants executing trust-related actions by age categories.

Total Trustworthy shop

Age categories 18-29 30-44 45-54 55+ 18-29 30-44 45-54 55+

n % n % n % n % n % n % n % n %

General terms and conditions 14 13 45 23 25 14 22 13 5 6 21 14 16 13 12 10

Impress / Contact 15 14 44 23 41 23 28 17 9 11 31 21 32 27 21 18

Shipping terms 19 18 41 21 31 17 26 15 8 10 13 9 23 19 10 9

Cancellation terms 21 20 40 21 35 20 24 14 10 12 18 12 20 17 10 9

Data security 3 3 13 7 9 5 14 8 1 1 6 4 9 8 8 7

Help / FAQ 7 7 21 11 18 10 10 6 3 4 7 5 3 3 3 3

Mouseover event on trustmark (e-com) 18 17 31 16 33 19 36 21 11 13 25 17 23 19 27 23

Mouse click on trustmark (e-com) 5 5 9 5 11 6 11 7 3 4 7 5 9 8 10 9

Mouseover event on trustmark (tech. insp.) 14 13 24 12 25 14 30 18 -* -* -* -* -* -* -* -*

Mouse click on trustmark (tech. insp.) 3 3 2 1 8 4 5 3 -* -* -* -* -* -* -* -*

Veiled scam shop Obvious scam shop

Age categories 18-29 30-44 45-54 55+ 18-29 30-44 45-54 55+

n % n % n % n % n % n % n % n %

General terms and conditions 5 6 22 15 9 7 9 8 5 6 27 18 14 10 12 9

Impress / Contact 8 9 26 17 25 20 21 18 12 13 40 26 33 24 24 19

Shipping terms 11 13 23 15 17 14 17 14 13 15 27 18 19 14 17 13

Cancellation terms 10 12 23 15 19 15 17 14 15 17 29 19 24 18 14 11

Data security 3 3 7 5 4 3 8 7 -* -* -* -* -* -* -* -*

Help / FAQ 3 3 7 5 6 5 6 5 6 7 18 12 15 11 7 5

Mouseover event on trustmark (e-com) 13 15 23 15 22 18 27 23 -* -* -* -* -* -* -* -*

Mouse click on trustmark (e-com) 4 5 6 4 7 6 30 25 -* -* -* -* -* -* -* -*

Mouseover event on trustmark (tech. insp.) 14 16 24 16 25 20 5 4 -* -* -* -* -* -* -* -*

Mouse click on trustmark (tech. insp.) 3 3 2 1 8 7 5 4 -* -* -* -* -* -* -* -*

no significant effects were found for age, frequency of

Internet use at work and frequency of online purchase

on the choice of the online store.

Significant differences in the visits and choice

of online stores were found between male and fe-

male participants, with female participants visiting

and buying more often in the trustworthy store. How-

ever, this difference might be explained by the name

of the trustworthy online store, which might be more

attractive to female participants. We therefore do

not want to interpret this result as a causal effect of

gender. Furthermore, while female participants com-

pared stores more often, both genders bought most

often in the obvious scam store. These findings are

in stark contrast to prior research finding men and

individuals with higher educational level to have a

higher risk of visiting non-trustworthy online stores

and therefore are at risk of being victims of online

scam stores (Georgiev, 2021). However, the previous

study used telephone interviews to examine risky be-

havior with regard to online shopping, therefore, male

being more pronounced to become victims in this

study might also be due to social desirable response

behavior. Our study minimized the impact of social

desirable behavior by veiling the purpose of the study

and observing behavior directly. Participants in the

condition including time pressure reported more sub-

jective feelings of time pressure and spent less time in

the study. However, it did not have a significant effect

on the choice of the online store for the purchase.

To answer the research questions, participants

seemed to have some knowledge of or interest in

trust indicators, however, other factors such as pric-

ing seem to exceed these. Also, the present study did

not find any personal or contextual factors to have sig-

nificant impact on the decision in which online store

participants would buy. An association was found

between the amount of trust-related actions and the

choice of the online store, such as participants who

bought in the trustworthy online store executed more

trust-related actions than participants who bought in

scam stores. As the tested factors, such as age, gen-

der, educational level, frequency of online purchase

behavior, frequency of Internet usage at work, or time

pressure did not show significant impact, it remains

unclear what characterizes individuals who are able

to distinguish between trustworthy and scam stores.

5.1 Implications

Personal and contextual factors of the present study

were not able to differentiate between individuals at

risk for scam. This raises the question of whether

there are factors that characterize a target group for

intervention, or whether measures should be defined

for the population as a whole. While the security com-

munity already provides extensive information about

online scams, there still seems to be a gap between the

SECRYPT 2024 - 21st International Conference on Security and Cryptography

566

information available and the information that ends up

with the customer. Therefore, education about scam

stores and how to identify them might need even more

attention or it might need to be provided in a different

way. One indicator the present study seems to reveal

is trustmarks. Therefore, it might be useful to educate

individuals about trustmarks and how to check them,

as well as to encourage online stores to implement

trustmarks on their websites. Trainings could also be

an effective way to educate individuals about the risks

of scam stores and how to avoid them.

5.2 Conclusion

In this paper we used an online simulation study de-

sign to examine user behavior during online shopping

with regard to trust indicators. We found that only a

minority of the participants executed trust-related ac-

tions and most participants bought in the obvious fake

store – probably due to its low pricing or its name and

visual appearance. The study did not reveal any per-

sonal or contextual factors significantly influencing

the decision for buying in a specific store. While there

were significant gender-related differences in the ini-

tial selection of a store, the majority of the purchases

were still made in the obvious scam store. These find-

ings can provide a foundation for future research on

user perception of trust in online shopping scenarios.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

SBA Research (SBA-K1) is a COMET Centre within

the COMET – Competence Centers for Excel-

lent Technologies Programme and funded by BMK,

BMAW, and the federal state of Vienna. COMET is

managed by FFG.

REFERENCES

Almousa, M. (2011). Perceived risk in apparel online shop-

ping: a multi dimensional perspective. Canadian So-

cial Science, 7(2):23–31.

Barker, C., Pistrang, N., and Elliott, R. (2015). Research

methods in clinical psychology: An introduction for

students and practitioners. John Wiley & Sons.

Beltzung, L., Lindley, A., Dinica, O., Hermann, N., and

Lindner, R. (2020). Real-time detection of fake-shops

through machine learning. In 2020 IEEE International

Conference on Big Data.

Carpineto, C. and Romano, G. (2017). Learning to

detect and measure fake ecommerce websites in

searchengine results. In Proceedings of the Interna-

tional Conference on Web Intelligence, WI ’17. ACM.

Competition, A. and Commission, C. (2023). Online shop-

ping scams.

Cranor, L. F. (2006). What do they” indicate?” evalu-

ating security and privacy indicators. Interactions,

13(3):45–47.

Egelman, S., Tsai, J., Cranor, L. F., and Acquisti, A. (2009).

Timing is everything? The effects of timing and place-

ment of online privacy indicators. In Proceedings of

the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Com-

puting Systems.

Farnsworth, B. (2019). How are simulations used in human

behavior research?

Frik, A. and Mittone, L. (2019). Factors influencing the per-

ception of website privacy trustworthiness and users’

purchasing intentions: The behavioral economics per-

spective. Journal of theoretical and applied electronic

commerce research, 14(3):89–125.

Ganguly, B., Dash, S. B., Cyr, D., and Head, M. (2010).

The effects of website design on purchase intention in

online shopping: the mediating role of trust and the

moderating role of culture. International Journal of

Electronic Business, 8(4-5):302–330.

Georgiev (2021). Fake shop in internet.

Gesellschaft,W. (2023). Erhebungsmethode richtig

w¨ahlen: Befragung oder beobachtung?

Hao Suan Samuel, L., Balaji, M., and Kok Wei, K. (2015).

An investigation of online shopping experience on

trust and behavioral intentions. Journal of Internet

Commerce, 14(2):233–254.

Krol, K., Spring, J. M., Parkin, S., and Sasse, M. A. (2016).

Towards robust experimental design for user studies in

security and privacy. In The LASERWorkshop: Learn-

ing from Authoritative Security Experiment Results.

¨

Ozg

¨

uven, N. (2011). Analysis of the relationship between

perceived security and customer trust and loyalty in

online shopping. Chinese Business Review, 10(11).

Rattanawicha, P. and Esichaikul, V. (2005). What makes

websites trustworthy? A two-phase empirical study.

International journal of electronic business, 3(2):110–

136.

Verster, J. C., van de Loo, A. J., Adams, S., Stock, A.-

K., Benson, S., Scholey, A., Alford, C., and Bruce,

G. (2019). Advantages and limitations of naturalis-

tic study designs and their implementation in alco-

hol hangover research. Journal of clinical medicine,

8(12):2160.

Wadleigh, J., Drew, J., and Moore, T. (2015). The ecom-

merce market for ”lemons”: Identification and analy-

sis of websites selling counterfeit goods. In Proceed-

ings of the 24th International Conference on World

Wide Web.

Safe or Scam? An Empirical Simulation Study on Trust Indicators in Online Shopping

567