Emotions-Based Training: Enhancing Aviation Performance

Through Self-Awareness and Mental Preparation,

Coping with Stress and Emotions

Frederic Beltran

Independent Consultant, France

Keywords: Evidence-Based Training (EBT), Crew Ressource Management (CRM), Competencies, Self-Awareness,

Emotion, Stress, Performance, Cognition, Mental Preparation, Coping, Aviation, Sport, Imagery, Breathing,

Self-Talk, Relaxation, Resilience, Mind-Body Relation.

Abstract: Commercial aviation has achieved remarkable levels of reliability, evidenced by the exceptionally safe year

recorded in 2023. However, the rarity of incidents means that unexpected events can have significant conse-

quences for crew capacities and competencies. Evidence-Based Training (EBT) and Crew Resource Mana-

gement (CRM) programs have long been instrumental in fostering effective teamwork and technical profi-

ciency among flight crews. However, an emerging area of focus within aviation training pertains to the psy-

chological aspects of pilot performance, particularly in managing stress, resilience and enhancing self-awa-

reness. High-level sports have developed a range of mental preparation and sports psychology tools to equip

athletes to manage unforeseen situations and adapt accordingly. Pilots, akin to high-level athletes, must per-

form under pressure, adapt to the unexpected, and maintain cognitive and analytical capabilities. These tools

are equally applicable to pilots facing unconventional scenarios. Drawing inspiration from the field of sports

psychology, this article explores how mental conditioning techniques can be integrated into Competencies

frameworks to optimize pilot training methodologies.

1 INTRODUCTION

This article aims to explore the potential contribution,

in terms of flight safety, of Mental Preparation tools

commonly used in high-level sports and their applica-

bility to the aviation industry. Specifically, it empha-

sizes the significance of "Self-Awareness" as a pre-

requisite to both technical and non-technical compe-

tencies outlined in the Manual of Evidence-Based

Training (EBT) ICAO doc9995AN/4.

In high-level sports, athletes undergo physical and

technical training to excel during competition, but

many also cultivate their mental skills to handle pres-

sure and adapt to the unknown, crucial prerequisites

for delivering the expected performance.

Similarly, commercial airline pilots must main-

tain a high level of proficiency to respond effectively

when unforeseen events jeopardize flight safety. They

must be capable of analyzing, making informed deci-

sions, and maintaining a safe flight path under ad-

verse conditions.

Unlike high-level athletes, however, pilots do not

typically receive individualized training on psycho-

logical states and stress management as part of their

initial training nor during their career. Instead, such

topics are covered at the crew level through Crew

Ressources Management (CRM) courses and simula-

tor training, focusing on predetermined competencies

within Evidence-based Training (EBT) programs.

Yet, from a human perspective, cognitive abilities

are only fully accessible when individuals are in a fa-

vorable psychological and physiological state, mean-

ing they may be unavailable in high-stress situations.

(Arnsten, 2009)

Modern-generation aircraft and complex systems

demand, in abnormal situations, not only procedural

adherence and piloting skills but also nuanced analy-

sis for understanding and adaptation.

To date, neither training programs nor regulations

adequately address this individual-level challenge.

Beltran, F.

Emotions-Based Training: Enhancing Aviation Performance Through Self-Awareness and Mental Preparation, Coping with Stress and Emotions.

DOI: 10.5220/0012924000004562

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Cognitive Aircraft Systems (ICCAS 2024), pages 21-28

ISBN: 978-989-758-724-5

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

21

2 EVIDENCE-BASED TRAINING

2.1 Background of Evidence-Based

Training (EBT)

The development of Evidence-Based Training (EBT)

stemmed from the need to address aircraft hull loss

and fatal accident rates by revising recurrent and

type-rating training for airline pilots. Traditional

training, based on early jet hull loss data, relied on

repeating events without addressing evolving risks.

With improved aircraft design and reliability, acci-

dents sometimes occurred in well-functioning aircraft

due to factors like inadequate situation awareness, as

seen in controlled flight into terrain incidents. This

shift necessitated a move away from a "tick box"

training approach towards a more evidence-based and

adaptive training methodology.

EBT prioritizes the development and evaluation of

key competencies, resulting in improved training out-

comes. Mastering a set of competencies enables pilots

to handle unforeseen flight situations not covered by

industry training.

Over the past two decades, data availability from

flight operations and training activities has greatly

improved. Sources like flight data analysis and air

safety reports offer detailed insights into risks en-

countered in flight operations. This data has under-

scored the necessity for Evidence-based Training

(EBT) initiatives. Additionally, it has helped define

the training concepts by highlighting variations in

training needs across different maneuvers and aircraft

generations.

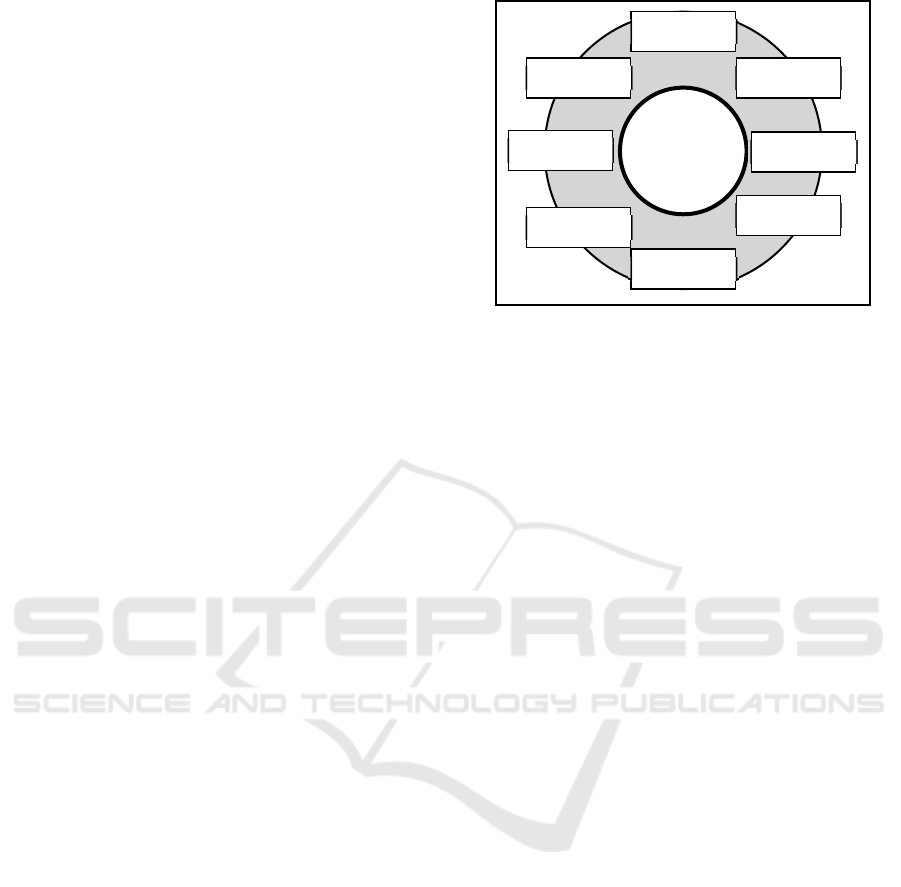

2.2 Competencies

EBT identifies core competencies that combine tech-

nical and non-technical knowledge, skills, and atti-

tudes, aligning training content with the requirements

of modern aviation (fig 1):

-

Technical competencies:

•

Application of procedures;

•

Aircraft Flight Path Management, automation;

•

Aircraft Flight Path Management, manual con-

trol.

-

Non-Technical competencies:

•

Communication;

•

Leadership and Teamwork;

•

Problem Solving and Decision Making;

•

Situation Awareness;

•

Workload Management.

Figure 1: Technical and non-technical competencies.

3 EMOTIONS, STRESS,

COGNITION

3.1 Emotions

While numerous theories and models have been pro-

posed to explain emotions, there is no consensus on a

single definition.

We can consider the neurobiological, cognitive,

psychological, behavioral, and even social dimen-

sions of emotions. (Van Kleef, 2022)

Emotions play a crucial role in decision-making

(Damasio, 2006), attention, motivation, memory (La-

chaux, 2011), social interactions, and of course,

enable a rapid response to events involving survival

by influencing behavior.

3.2 Stress

Stress (American Psychological Association APA

2018; Valencia-Florez, 2023) is a significant area of

study in our Western society currently. It has been the

subject of constant research, and our understanding of

it has evolved over time. Stress will be addressed be-

low by limiting the discussion to the topic that con-

cerns us: cognitive performance in dynamic situa-

tions.

3.2.1 Acute Stress

Necessary for survival, acute stress is an adaptive

reaction. Faced with a stressor, considered subjecti-

vely as such by the individual, a cascade of reactions

occurs, ranging from neurobiological, physiological,

psychological to behavioral aspects. Acute stress is li-

mited in time and requires recovery time. The conse-

PROCEDURES

AUTOMATION

COMMUNICATION

MANUAL

DECISION

MAKING

LEADERSHIP

TEAM

WO

R

K

SITUATION

AWARENESS

WORKLOAD

MANAGEMENT

ICCAS 2024 - International Conference on Cognitive Aircraft Systems

22

quences can be difficulties in attention, analysis, com-

munication, decision-making, degradation of coordi-

nation, and sometimes inappropriate responses to the

context (Staal, 2004).

3.2.2 Chronic Stress

Chronic stress is a disruption of the stress circuit with

multiple consequences (Marin, 2011). It develops

over time either by the constant presence of the

stressor or by an emotional marking that prevents the

organism from returning to balance. The effects of

chronic stress are deleterious and have consequences

on attention, memory, sleep, the immune system,

which tends to maintain or even further feed it.

3.2.3 Emotion, Stress and Cognition

Executive control is a set of cognitive processes that

enables the control and regulation of thoughts, emo-

tions, and behaviors. It allows for situational analysis,

perspective shifting, and decision-making, making it

indispensable in managing complex systems. It com-

plements automatic cognitive processes, which are

responses to familiar stimuli that do not require cons-

cious attention, yet are energetically economical.

These concepts are often described as "System 1; Sys-

tem 2" or "Automatic mode/Adaptive mode" (La-

chaux, 2011; Kahneman, 2011)

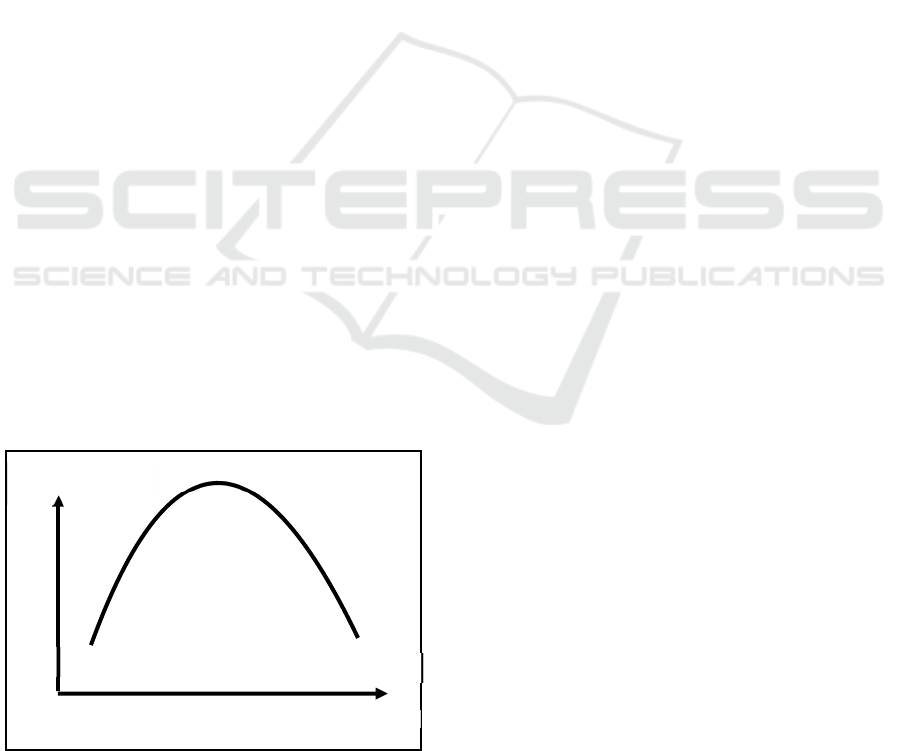

3.2.4 Stress and Performance

During abnormal or unknown events, where the out-

come is uncertain, acute stress adds to chronic stress

(Knauft, 2021), altering the functioning of the execu-

tive mode, which enables adaptation. Cognitive re-

gression under stress is well-documented in psycho-

logical and neuroscientific literature (Staal, 2004).

Figure 2: PreFrontal Cortex performance and dopamine/no-

radrenaline level.

In moments perceived as "stressful," the chemical

balance between noradrenaline and dopamine in the

prefrontal cortex (PFC), which houses a large part of

the executive system, no longer allows for nominal

synaptic functioning, influencing attention and

working memory (Oberauer, 2019), and consequently

affecting all functions that require analysis, perspec-

tive-taking, and reasoning.

This alteration can range from difficulty in regu-

lating attention to total cognitive paralysis, as in the

case of startle responses (Arnsten, 2009).

This leads to a tendency to operate more automa-

tically, with deeper brain areas (limbic system) where

old knowledge is stored continuing to function under

stress. The drawback is that responses may be de-

coupled from the context, and individuals may rely on

heuristics and be subject to biases in information pro-

cessing and reasoning.

Tools to restore balance exist and will be des-

cribed in the following sections.

3.2.5 Emotion and Stress

Emotion and stress mutually influence each other,

with each being able to fuel and amplify the other

(Epel, 2018). Strong emotion can generate significant

stress, which in turn can amplify emotion. It is not

possible to suppress emotions, but it is possible to

work on managing these emotions.

Furthermore, studies on mirror neurons also ex-

plain the contagion of emotions and therefore stress

(Gallese, 2001; Dimitroff, 2017). It may therefore

also be interesting to work on emotion regulation in

training in connection with visible negative conse-

quences to avoid contaminating a team or crew.

4 HUMANS AND COMPLEX

SYSTEMS

4.1 System Evolutions in Commercial

Aviation

The latest generation of airliners is simpler to use but

much more complex in design than older aircraft.

Automations are ubiquitous, and their use is strongly

recommended or mandated. Many systems and com-

puters allow the aircraft to be kept within a flight en-

velope that respects limitations without requiring si-

gnificant resources from the crew, even in degraded

conditions. Among other things, there are electric

controls, automatic engine and speed management,

multiple protections, simplified approach procedures,

Level of Do

p

amine o

r

Noradrenaline

Too low

(hypovigilance)

Too high

(Stress)

Optimal

Executif System

Performance

Emotions-Based Training: Enhancing Aviation Performance Through Self-Awareness and Mental Preparation, Coping with Stress and

Emotions

23

and some fully automatic maneuvers such as emer-

gency descent or TCAS trajectories to resolve trajec-

tory conflicts between two aircraft. The systematic

application of procedures contributes to safety and al-

lows crews to remain in a familiar environment.

Aircraft have reached remarkable levels of reliabi-

lity: "the commercial aviation sector recorded an ex-

ceptionally safe year in 2023" (IATA Annual Safety

Report 2023). The downside of these aircraft deve-

lopments is the delicate integration of humans, who

find themselves in a situation of monitoring an ultra-

reliable system but may experience significant sur-

prise effects when automation does not act correctly,

and this unexpectedly.

4.2 Simple Failure Handling

During failures, pilots are trained to use procedures,

often repeated in simulation, to deal with a large num-

ber of abnormal situations. These situations do not ge-

nerate particular stress, and the reliability of the latest

generation of aircraft means that failures are relati-

vely rare.

The aircraft will present the faulty system and dis-

play the corresponding checklist (C/L) on a dedicated

screen, with the items being few and sequenced in a

simple manner to normalize the situation quickly (an-

nunciated C/L).

System redundancy means that these simple fai-

lures will not lead to fundamental changes in flight

conduct or excessive workload.

4.3 Complex Failure Handling

More complex failures such as a fire or smoke in the

aircraft, inconsistent speed measurements, can gener-

ate a higher level of engagement than simple failures.

These failures will also be handled using announced

electronic checklists, which may include choices de-

pending on the situation analysis. Some of these

checklists will not be announced and will be at the

discretion of the crew after analysis (non-annunciated

C/L).

It may also be the case that a complex failure in-

duces multiple checklists and requires flight adapta-

tion due to degraded aircraft performance or the ur-

gency to land at the nearest accessible airport, and a

renunciation of the initial plan.

4.4 The Need of Advanced Analytical

Capabilities

During multiple failures or failures outside the scope

of procedures, the aircraft may have characteristics

completely different from the initial aircraft. The pilot

finds himself in an unknown situation and under high

workload, thereby limiting his resources. The case of

Quantas 032 in November 2010 is the most well-

known example, with a multitude of failures that did

not allow understanding the actual state of the aircraft

without lengthy analysis, which took more than 45

minutes on that day.

The need for adaptation is crucial, and the cogni-

tive resources of pilots must be available despite sur-

prise or significant stress.

5 COPING WITH EFFECT OF

STRESS IN HIGH-LEVEL

SPORT

There is relevance in focusing on mental preparation

in athletes since the issues faced by athletes/pilots are

similar. In both cases, performing at a specific mo-

ment and under pressure is required.

5.1 Mental Conditioning (Sport

Psychology)

"Mental preparation is the set of steps, methods, and

techniques allowing for the development and optimi-

zation of the athlete's psychological resources in or-

der to improve performance and/or well-being."

(Sève, & Poizat).

5.2 Tools Used

Optimizing performance means that the level

achieved in training should at least be reached in com-

petition.

To do this, many tools aim to manage stress, whether

chronic or acute, and work on adaptability during un-

expected events.

5.2.1 Mental Imagery

The process by which a person generates, manipu-

lates, and uses mental representations to understand

the world around them, solve problems, plan actions,

or recall past experiences (Et, 2021).

This mental capacity plays an essential role in var-

ious domains, such as learning, memory, creativity,

and sports performance. It also allows for preparing

for an action and mentally rehearsing it.

Aviation: Visualizing an approach before executing

it; practicing procedures, correcting sequences...

ICCAS 2024 - International Conference on Cognitive Aircraft Systems

24

5.2.2 Breathing

Voluntary abdominal breathing helps direct attention

away from the pressure field and regulate the auto-

nomic nervous system (Laborde, S, 2022). It is an es-

sential tool in mental preparation because it provides

space between the perception of stress and the re-

sponse to be made (Haynes et al., 2024).

Aviation: Being able to focus on breathing during un-

expected events. Knowing how to regulate oneself to

regain cognitive abilities.

5.2.3 Temporization

Manipulation of slow and simple motor movements

may be an effective means to attenuate autonomic

arousal (Stearns, 2017) and also allows for analysis

and adaptive mode, a step back similar to breathing.

Aviation: Physically stepping back from the situation.

"Sit on your hands." Knowing how to slow down

one's colleague by regulating their speech pace, for

example, to bring them to a compatible activation

level with the situation.

5.2.4 Relaxation (Mind-Body Connection)

Relaxation allows for tension release and induces

"mental" relaxation as well (Meissner, 2006). The re-

verse is also true: energizing the body in case of

hypovigilance allows for regaining cognitive abilities

(Jazaieri and al. 2012; Morone and al. 2007).

Aviation: Identifying tensions. Knowing how to re-

lease them to gain both physical and mental fluidity.

5.2.5 Acceptance and Commitment

Inspired by Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

(ACT), accepting the situation allows for committing

to a solution (Hayes, Wilson, Strosahl, 1980; Mon-

estes, Villatte 2017). This movement towards a solu-

tion reduces stress and enables quicker adaptation to

the situation.

Aviation: Accepting the situation at hand to quickly

initiate a solution, adapting accordingly.

5.2.6 Perspective Shifting

Working on psychological flexibility (Monestes, Vil-

latte, 2017). Considering a situation from a different

angle than the one naturally presented allows for new

interpretations and considering other solutions. This

tool contributes to enhancing individual resilience.

Aviation: Being able to change the point of view, con-

sider multiple options. Listening to other suggestions.

5.2.7 Self Talk

Internal discourse can be motivational or instructional

(Latinjak and al, 2023), helpful, or detrimental. Iden-

tifying words that serve performance is a way to re-

main effective and perseverant. It is noteworthy for

trainers or instructors that a significant portion of the

words used by the athlete (the pilot) often comes from

the words used by the coach (Boudreault, Trottier,

Provencher 2016).

Aviation: Understanding the quality of one's internal

discourse, knowing if it is helpful or detrimental. Act-

ing accordingly.

5.3.8 Athlete Ecology, Goal Setting,

Motivation

These approaches help work on chronic stress. We

have seen the importance of considering chronic

stress in the general regulation of emotions and stress,

allowing for a functionally optimal brain. (Sagy,

2002).

Aviation: Understanding that accumulated stress re-

duces the margin before cognitive tipping. Knowing

how to recognize one's state. Sharing as needed.

6 SELF AWARENESS IN THE

MIDDLE OF THE

COMPETENCY MODEL?

6.1 Example of Accidents Where Stress

Has Led to Overreactions or

Cognitive Incapacitation

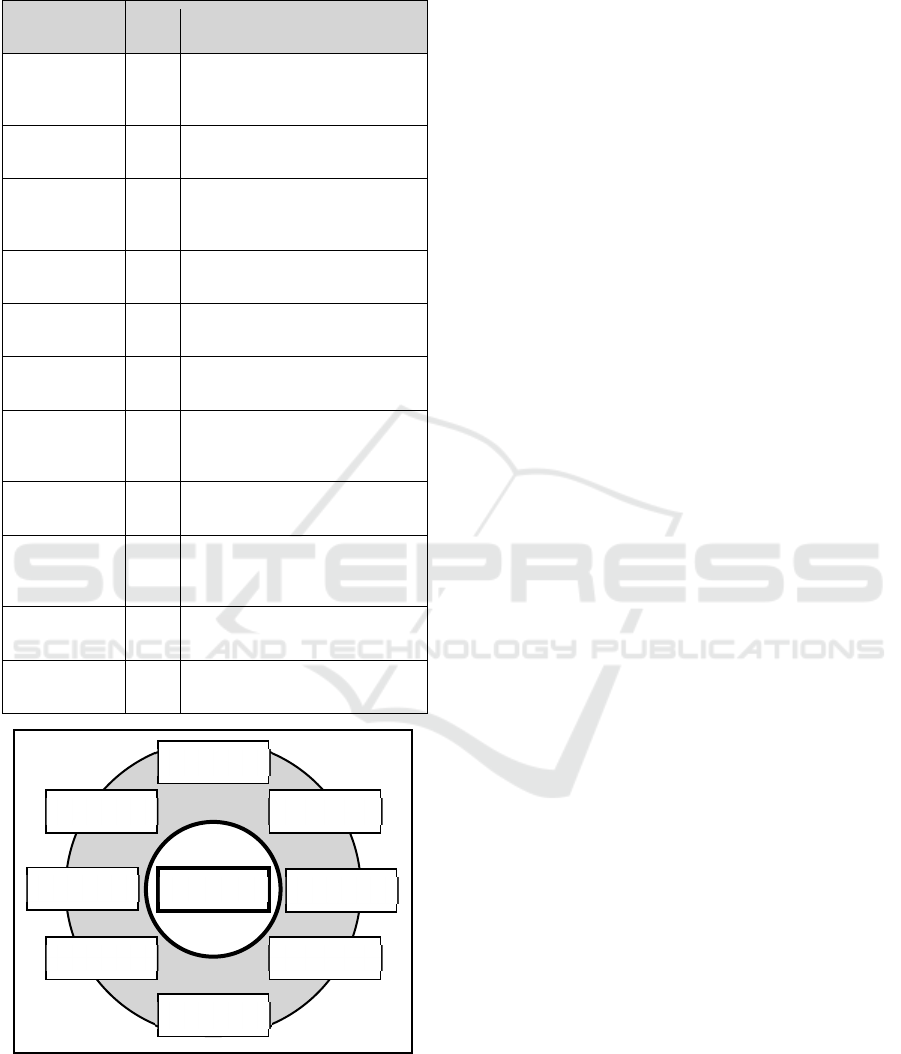

In all these events (see table 1), incapacitation due to

stress, whether cognitive or physical, was noted. All

competencies and CRM skills were affected, leading

to the accident.

6.2 The Need to Place Self-Awareness

at the Core of the Skills Model

As mentioned earlier, emotions and stress can have

detrimental effects on analytical abilities, communi-

cation, decision-making, and motor skills. All skills

can be impaired under stress (McClernon and al,

2011; Cahill, and al, 2021; Sadovnikova and al,

2023).

Emotions-Based Training: Enhancing Aviation Performance Through Self-Awareness and Mental Preparation, Coping with Stress and

Emotions

25

Table 1: Example of accidents where stress led to to over-

reactions or cognitive incapacitations.

Company Year Keys words

American Air-

lines 965

1995

… desire to hurry the arrival; crew

appeared to be confused, unaware

of thei

r

location…

AeroPeru 604 1996

…mental confusion… confusion in

assessmen

t

…

Korean Air 801 1997

failure to execute the non-precision

approach; failure to effectively

monitor; fatigue; inhibition

AtlasJet 4203 2007

Loss of situational awareness; spa-

tial disorientation;

Spanair 5022 2008

inability to identify and solve the

situation ; confusion.

SantaBarbara

Airline 518

2008

crew (…) became disoriented…

Air France 447 2009

…deterioration of the crew coope-

ration leading to total loss of cogni-

tive control of the situation.

Colgan Air

3407

2009

…monitoring failures, pilot profes-

sionalism, fatigue.

Air India

Express 812

2010

…persistence in continuing with

the landing; sleep inertia; impaired

judgment.

Air Asia 8501 2014

…Inappropriate reactions; Miscom-

munication

TransAsia

Airways 235

2015 … impaired judgment. Confusion.

Figure 3: Self awareness at the core of the skill model.

We have seen that a significant number of acci-

dents are due to inappropriate reactions to a situation

that could have been controllable. These accidents are

more numerous than those following an engine fail-

ure. Although the relationship between emotion, cog-

nition, and decision-making is well established (Lev-

ine, 2022), the engine failure is over-trained, while

"Self-Knowledge" is not. Yet, it seems indispensable

(fig 3).

6.3 Reasons Why Self-Awareness Is

Still not Trained

There are several reasons why this approach is not

taught in aviation training:

-

A cultural bias that believes that following

procedures alone is sufficient for safety.

-

The problem is not fully understood, which is sur-

prising since it is experienced in other high-risk ac-

tivities, especially in military aviation.

-

Difficulty for an organization to control or quantify

teachings, as Self-Knowledge is difficult to eva-

luate in the short term and can only be assessed in

the face of exposure to the unexpected. The use of

Human Factors-oriented Experience Feedback

(EFB) is not yet developed in this direction.

-

Instructional problem from the start of training. A

young pilot will only hear about these topics when

joining a major airline.

-

The time devoted to integrating the effects of stress

or emotions is almost nonexistent in initial trai-

ning, no tools are provided, as the focus is on tech-

nical learning and aircraft handling. In this sense,

this "Self-Knowledge," even if known, is not per-

ceived as important.

-

Flight School instructors are often pilots who are

removed from these considerations due to their

own training and are neither trained nor convinced

of the relevance of this aspect of training. Many

provide a technical response to an emotional pro-

blem.

-

Regulation does not address individual perfor-

mance, which should be integrated as a prerequi-

site for accessing skills. This topic may then be

considered secondary by operators.

6.4 Instructors Training

As with the transition from traditional instruction to

Evidence-Based Training (EBT), Self-Knowledge

training is necessary (Soundara Pandian and al, 2023).

By understanding basic human functioning and

the importance of being able to access one's full cog-

nitive and physical capabilities in the event of unex-

pected situations, instructors can provide tailored and

SELF

AWARENESS

PROCEDURES

AUTOMATION

COMMUNICATION

MANUAL

DECISION

MAKING

LEADERSHIP

TEAMWOR

K

SITUATION

AWARENESS

WORKLOAD

MA

N

A

G

EME

N

T

ICCAS 2024 - International Conference on Cognitive Aircraft Systems

26

personalized tools that will be a prerequisite and com-

plement to CRM skills.

Self-Knowledge should be integrated into simula-

tor sessions, practiced, and debriefed afterward. It

should be an integral part of training.

Without turning instructors into Mental Prepara-

tion Specialists, it is easy to provide them with suffi-

cient knowledge to move beyond the descriptive and

deliver tools adapted to pilots' issues during training.

7 ENHANCING PILOT

TRAINING

Crew Resource Management (CRM) courses are de-

livered annually to crews. They are covered by a pro-

gram established by the regulatory authority and must

address CRM topics on a triennial basis. To date,

there is no formal demand for Self-Knowledge trai-

ning. It is also not integrated into simulator sessions.

It would be essential to teach the techniques men-

tioned earlier from the beginning of aviation activity

so that the tools are naturally used when needed.

A young pilot must recognize their stress (Lupien

et al., 2022), be able to express their emotions from

their first hours of flight, and understand their stress.

It's a matter of safety. They should be offered means

to address it. However, there is often still a barrier to

sharing doubts, fears, or problems that have solutions.

Pilots empirically build solutions that likely already

exist as they gain experience and skills.

Recognizing emotions and stress should be syste-

matic in high-risk systems, given the importance of

maintaining cognitive abilities under stress.

Paradoxically, some airlines have entities that ad-

dress the well-being and stress of flight crews:

- The CIRP (Critical Incident Response Plan) in-

tervenes after an incident during a flight, poten-

tially impacting chronic stress or even causing

post-traumatic syndrome.

- GAIN (Gestion et Accompagnement Individuel

des Navigants) assists pilots lacking confidence

or facing specific problems in their professional

lives. These two entities are not involved in trai-

ning.

8 CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the findings of this study underscore

the critical role of self-awareness in the context of air-

line pilot training. Through an examination of stress

and emotion management tools drawn from the do-

main of high-level sports, this research elucidates the

potential for enhancing pilots' resilience and, conse-

quently, the safety of commercial flights. The discus-

sion has highlighted the inherent parallels between

the demands faced by high-level athletes and airline

pilots, emphasizing the need for a holistic approach to

pilot training that encompasses both technical profi-

ciency and psychological preparedness.

By incorporating principles of self-awareness,

mental imagery, breathing techniques, temporal ma-

nipulation, relaxation, acceptance, perspective shif-

ting, and self-talk into pilot training curricula, avia-

tion training institutions can better equip pilots to na-

vigate the complexities of the aviation environ-

ment.Moreover, the identification of barriers to the

integration of such strategies, as outlined in this

study, underscores the necessity for systemic changes

within aviation training programs and regulatory fra-

meworks.

Looking ahead, it is imperative for aviation stake-

holders to prioritize the development and implemen-

tation of evidence-based training programs that ad-

dress the psychological dimensions of pilot perfor-

mance. By doing so, the aviation industry can foster

a culture of continuous improvement, resilience, and

safety, ensuring that pilots are equipped with the

necessary tools to confront the challenges of modern

aviation. A step to Emotion-Based Training?

REFERENCES

Accident Quantas 032 (2010), https://www.faa.gov/les-

sons_learned/transport_airplane/accidents/VH-OQA

Accident American Airlines 965, (1995)

https://www.faa.gov/lessons_learned/transport_air-

plane/accidents/N651AA

Accident aeroperu604, https://skybrary.aero/sites/de-

fault/files/bookshelf/1719.pdf

Accident KoreanAir801 https://www.ntsb.gov/investiga-

tions/accidentreports/reports/aar0001.pdf

Accident AtlasJet 4203 https://aviation-safety.net/asndb/32

1830

Accident SpanAir 5022 https://reports.aviation-safety.net/

2008/20080820-0_MD82_EC-HFP.pdf

Accident AF447 2009 https://bea.aero/docspa/2009/f-

cp090601/pdf/f-cp090601.pdf

Accident ColganAir 3407 https://www.ntsb.gov/investiga-

tions/accidentreports/reports/aar1001.pdf

Accident TransAsia airway 812 https://www.ttsb.gov.tw/

english/16051/16113/16114/16531/post

Antonio Damasio (2006) L’erreur de Descartes.

Arnsten, A. F. T. (2009). Stress signalling pathways that im-

pair prefrontal cortex structure and function. In Nature

Reviews Neuroscience (Vol. 10, Issue 6).

Emotions-Based Training: Enhancing Aviation Performance Through Self-Awareness and Mental Preparation, Coping with Stress and

Emotions

27

Ban, Y., Karasawa, H., Fukui, R., & Warisawa, S. (2022).

Development of a Cushion-Shaped Device to Induce Res-

piratory Rhythm and Depth for Enhanced Relaxation and

Improved Cognition. Frontiers in Computer Science, 4.

Cahill, J., Cullen, P., Anwer, S., Wilson, S., & Gaynor, K.

(2021). Pilot Work Related Stress (WRS), Effects on

Wellbeing and Mental Health, and Coping Methods. In-

ternational Journal of Aerospace Psychology, 31(2).

Daniel Kahneman, (2011), « Thinking, Fast and slow »

De Boeck Supérieur.Accident Quantas 032 (2010),

Dimitroff, S. J., Kardan, O., Necka, E. A., Decety, J., Ber-

man, M. G., & Norman, G. J. (2017). Physiological dy-

namics of stress contagion. Scientific Reports, 7(1).

EBT ICAO Manual Doc 9995 Manual of Evidence Based

Training

Epel, E. S., Crosswell, A. D., Mayer, S. E., Prather, A. A.,

Slavich, G. M., Puterman, E., & Mendes, W. B. (2018).

More than a feeling: A unified view of stress measure-

ment for population science. Frontiers in Neuroendocri-

nology, 49, 146–169.

Et.al, F. F. K. (2021). Mental Imagery And Performance Im-

provement Of Basketball Athletes In The 16-18 Year

Age Group. Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathema-

tics Education (TURCOMAT), 12(3)

Guillot, A., & Debarnot, U. (2019). Benefits of motor im-

agery for human space flight: A brief review of current

knowledge and future applications. In Frontiers in Phys-

iology (Vol. 10, Issue APR).

Haynes, A. C., Kent, C., & Rossiter, J. (2024). Just a Breath

Away: Investigating Interactions with and Perceptions of

Mediated Breath via a Haptic Cushion. Proceedings of

the Eighteenth International Conference on Tangible,

Embedded, and Embodied Interaction.

Jazaier H, Goldin PR, WernerK, Ziv M, Gross JJ (2012) «

Effect of progressive muscle relaxation on attentional

performance. »

Jean-Louis Monestes, Matthieu Villatte, (2017), La thérapie

d’acceptation et d’engagement ACT. Flexibilité psycho-

logique.

Jean-Philippe LACHAUX, (2011) « Le cerveau attentif ».

Joëls, M., & Baram, T. Z. (2009). The neuro-symphony of

stress. In Nature Reviews Neuroscience (Vol. 10, Issue 6).

Kavanagh, D. J. (1986). Stress, Appraisal and Coping. Laza-

rus and S. Folkman, New York: Springer, 1984, pp. 444.

Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 14(4).

Knauft, K., Waldron, A., Mathur, M., & Kalia, V. (2021).

Perceived chronic stress influences the effect of acute

stress on cognitive flexibility. Scientific Reports, 11(1).

Laborde, S., Zammit, N., Iskra, M., Mosley, E., Borges, U.,

Allen, M. S., & Javelle, F. (2022). The influence of

breathing techniques on physical sport performance: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. International Re-

view of Sport and Exercise Psychology.

Latinjak, A. T., Morin, A., Brinthaupt, T. M., Hardy, J., Hat-

zigeorgiadis, A., Kendall, P. C., Neck, C., Oliver, E. J.,

Puchalska-Wasyl, M. M., Tovares, A. v., & Winsler, A.

(2023). Self-Talk: An Interdisciplinary Review and

Transdisciplinary Model. Review of General Psychol-

ogy, 27(4).

Levine, D. (2022). Neuroscience of Emotion, Cognition, and

Decision Making: A Review. Medical Research Ar-

chives, 10(7).

Lupien, S. J., Leclaire, S., Majeur, D., Raymond, C., Jean

Baptiste, F., & Giguère, C. E. (2022). ‘Doctor, I am so

stressed out!’ A descriptive study of biological, psycho-

logical, and socioemotional markers of stress in indivi-

duals who self-identify as being ‘very stressed out’ or

‘zen.’ Neurobiology of Stress, 18.

Marin, M. F., Lord, C., Andrews, J., Juster, R. P., Sindi, S.,

Arsenault-Lapierre, G., Fiocco, A. J., & Lupien, S. J.

(2011). Chronic stress, cognitive functioning and mental

health. In Neurobiology of Learning and Memory (Vol.

96, Issue 4).

McClernon, C. K., McCauley, M. E., O’Connor, P. E., &

Warm, J. S. (2011). Stress training improves perfor-

mance during a stressful flight. Human Factors, 53(3).

Meissner, W. W. (2006). Psychoanalysis and the mind-body

relation: Psychosomatic perspectives. In Bulletin of the

Menninger Clinic (Vol. 70, Issue 4).

Moisan, M. P., & le Moal, M. (2012). Overview of acute and

chronic stress responses. In Medecine/Sciences (Vol. 28,

Issues 6–7).

Morone, N. E., & Greco, C. M. (2007). Mind-body interven-

tions for chronic pain in older adults: A structured re-

view. In Pain Medicine (Vol. 8, Issue 4).

Oberauer, K. (2019). Working memory and attention - A con-

ceptual analysis and review. In Journal of Cognition

(Vol. 2, Issue 1).

Sadovnikova, N. O., Pomelova, T. A., & Ustyantseva, O. M.

(2023). the relationship of occupational stress and coping

strategies in civil aviation pilots. Russian Journal of Ed-

ucation and Psychology, 14(6).

Sagy, S. (2002). Moderating factors explaining stress reac-

tions: Comparing chronic-without-acute-stress and

chronic-with-acute-stress situations. Journal of Psychol-

ogy: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 136(4).

Sève, C., & Poizat, G. (2009). « Préparation mentale en sport:

Fondements et outils ».

Soundara Pandian, P. R., Balaji Kumar, V., Kannan, M., Gu-

rusamy, G., & Lakshmi, B. (2023). Impact of mental

toughness on athlete’s performance and interventions to

improve. In Journal of Basic and Clinical Physiology and

Pharmacology (Vol. 34, Issue 4).

Staal, M. a. (2004). Stress, cognition, and human perfor-

mance: A literature review and conceptual framework.

NASA Technical Memorandum (p. 168).

Stearns, S.S., Fleming, R. & Fero, L.J. (2017) Attenuating

Physiological Arousal Through the Manipulation of Sim-

ple Hand Movements. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback

42, 39–50

Valencia-Florez, K. B., Sánchez-Castillo, H., Vázquez, P.,

Zarate, P., & Paz, D. B. (2023). Stress, a Brief Update. In

International Journal of Psychological Research (Vol.

16, Issue 2).

Van Kleef, G. A., & Côté, S. (2022). The Social Effects of

Emotions. In Annual Review of Psychology (Vol. 73).

Véronique Boudreault, Christiane Trottier, Martin D. Pro-

vencher; (2016) « Discours interne en contexte sportif :

synthèse critique des connaissances », Dans Staps/1

(n° 111), pages 43 à 64

Vittorio Gallese, Giacomo Rizzolatti, Luciano Fadiga (2001)

The “shared manifold” hypothesis: From mirror neurons

to empathy. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 8(6–7).

ICCAS 2024 - International Conference on Cognitive Aircraft Systems

28