Airline Pilots’ Perceived Operational Benefit of a Startle and Surprise

Management Method: A Qualitative Study

D. M. L. Vlaskamp

1

, A. Landman

2a

, J. M. van Rooij

3

, W-C. Li

4b

and J. Blundell

4c

1

Coventry University, Coventry, U.K.

2

Delft University, Delft, The Netherlands

3

Netherlands Aerospace Centre, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

4

Cranfield University, Bedfordshire, U.K.

Keywords: Pilot Decision Making, Stress, Crew Resource Management, Pilot / Crew Behaviour.

Abstract: Startle and surprise can impair pilot performance and jeopardize flight safety. Self-management methods have

been developed by the industry to address this acute source of stress, however, qualitative insights from pilots

describing the quality of these methods are lacking. Ten semi-structured interviews with airline pilots, who

had been taught a self-management method, were analyzed using thematic analysis). Pilots considered the

method useful and reported positive effects (e.g., decrease in stress) when applying the method during

operations. Pilots reported that the method was not often performed in full; specific steps were employed

based on perceived benefit. Establishing fellow pilot status and situation awareness was considered most

important, addressing own physical startle symptoms (e.g., muscle tension) were deemed less important.

Pilots reported an urge to “act” rather than use the method, which is expected as the method aims to induce a

pause and mitigate erroneous impulsive decisions. Barriers to applying the method included the difficult

recognition of startle and surprise, and situational context. Suggested improvements for training dealt with

recognition and sharing experiences from peers. The findings of the research provide directions for pilot

training for startle and surprise. Future research will explore these pilot perceptions in a larger representative

sample.

1 INTRODUCTION

Startle or surprise reactions have been implicated as a

contributing factor in several high-profile loss-of-

control aviation accidents, such as Air France 447 in

2009 (Landman, 2017a). The increased level of safety

in aviation has created an “unconscious expectation

of normalcy amongst pilots” (Martin et al.,2015). In

the rare cases where things do go wrong, they often

go wrong unexpectedly, and this can lead to a startle

or surprise reaction in the pilot.

Startle is defined as a sudden involuntary reaction

to an intense stimulus, such as a sudden loud noise

(Rivera et al., 2014). The initial startle reflex occurs

very fast, and is characterized by eye-lid closure,

contraction of the face, neck and skeletal muscles, an

increase in heart rate and arrest of ongoing behaviour

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3678-9210

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8825-3701

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4029-0773

(Rivera et al., 2014,). Attentional resources are

directed towards the stimulus as a mechanism of

threat appraisal (Martin et al., 2015). If the stimulus

is perceived to be a real threat, the general stress

response will remain, or even increase in intensity

(Landman et al., 2017a, Martin et al., 2015). An

example of a startling situation in aviation is a

lightning strike, which is accompanied by a loud

bang.

Surprise is defined as “a cognitive-emotional

response to something unexpected, which results

from a mismatch between one’s mental expectations

and perceptions of one’s environment” (Rivera et al.,

2014). It is of longer duration than startle. If this

mismatch cannot be resolved, a feeling of stress and

loss of control of the situation can arise, leading to a

loss of situation awareness and ultimately cognitive

Vlaskamp, D., Landman, A., van Rooij, J., Li, W. and Blundell, J.

Airline Pilots’ Perceived Operational Benefit of a Startle and Surprise Management Method: A Qualitative Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0012927800004562

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Cognitive Aircraft Systems (ICCAS 2024), pages 29-34

ISBN: 978-989-758-724-5

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

29

lockup (Landman, 2017a). Attentional narrowing

takes place, as attention is focused on trying to

confirm the (incorrect) cognitive “frame”, instead of

seeking out additional information (Landman et al.,

2017a)). Surprises are common in aviation, but often

inconsequential (Kochan et al., 2005). Surprise in

aviation often occurs in the presence of conflicting or

ambiguous cues that impede successful reframing.

For example, in situations where the automation does

not function as expected (automation surprise) or

where complicated failures occur without a clear

cause.

Startle and surprise (S&S) can occur together or

on their own (Field et al., 2018). The terms are often

used interchangeably in aviation (Rivera et al., 2014,

Landman et al., 2017a). The resultant stress response

impairs flight deck communication and decision

making (Martin et al., 2016, Landman et al., 2017b)

– compromising operational safety. Approaches to

mitigating S&S effects include startle exposure

through unpredictable and variable scenario

simulator training (Landman, et al., 2018). S&S

recovery techniques, alternatively, center around a

breathing technique and the timely reacquisition of

situation awareness (Field et al., 2018). Simulator

evaluations have revealed such methods to improve

pilot decision making (Field et al., 2018; Landman et

al., 2020). Though, anecdotal pilot feedback suggests

that methods are not used in full during relevant flight

operations (Field et al., 2018).

The current study evaluates pilot perceptions of a

S&S management technique that has been introduced

to the operational environment since 2017. The

method, from now on referred to as the “reset

method”, is an adapted version of the EASA S&S

management method (Field et al., 2018) and consists

of five steps, which can be selectively used as desired:

1) Announce that a “reset” will take place; 2) Take

physical distance (press back into the back of the seat,

to prevent fixation on one cue); 3) Breathe: inhale,

using abdominal breathing, and exhale slowly.

Repeat if necessary; 4) Tense and relax shoulder and

arm muscles, and; 5) Check the mental state of the

fellow crewmember(s). After completing the “reset”,

emphasis is placed on rebuilding situational

awareness carefully and methodically (by calling out

all observations before drawing conclusions).

To date no research has formally evaluated a S&S

management method in the operational environment.

This is critical as it is expected that the degree of S&S

is far greater in actual, possibly life-threatening,

situations (Field et al., 2018), which could make

pilots forget they can use the reset method. Hence,

research describing how pilots use these methods in

different operational contexts will demonstrate their

actual worth and explain how future method

optimization adaptations could be realized. This

research intends to address this current gap in

knowledge, through a series of interviews with pilots

from a major European airline where the “reset”

method has been in use for some time. The following

research objectives were established:

• Examine pilot perceptions of the operational

impact of S&S.

• Understand pilot views of the benefit of a S&S

management method.

• Explore possible inhibiting factors of a S&S

management method.

• Discover relevant training options / adjustments

to S&S management methods.

2 METHOD

2.1 Participants

Ten pilots from the same airline, trained in the same

method, participated (5 captains, 4 first officers, 1

second officer; 7/10 instructors, 3/10 female). Mean

flight experience was 7950 hours (SD = 3676.2),

predominantly on Boeing aircraft types (6 B737, 2

B777/787, 1 A330 and 1 Embraer pilot).

2.2 Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews were carried out in Dutch

and recorded via Teams. Interviews aimed to get

participants to talk about their S&S experiences.

After gathering demographic data and establishing

whether they had experienced S&S, questions were

asked about the effects of startle and surprise and the

perceived effectiveness of the method. Possible

inhibiting factors were discussed. For those that had

not experienced S&S, questions about the method’s

use in the simulator were asked. Approximately 600

minutes of audio data was collected and transcribed.

2.3 Thematic Analysis

Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis

(2016) was used, as it is suitable for providing

analyses of people’s experiences in relation to an

issue and for analysing factors that influence a

particular phenomenon. The transcripts were coded

immediately after each interview, and data grouped

into themes. In this way, data saturation was

determined using the method by Guest et.al. (2020)

ICCAS 2024 - International Conference on Cognitive Aircraft Systems

30

whereby interview data was collected until the point

that emergent thematic insights no longer occurred.

In the current study, saturation – the absence of

emergent (sub)themes - occurred by the eighth

interview. Coding reliability was determined using

triangulation - carried out by the project supervisor.

The coded quotes were divided into 5 main themes

and 20 subthemes. Initial agreement was at 80.2

percent, coding inconsistencies were discussed until

agreement between coders was met.

3 RESULTS

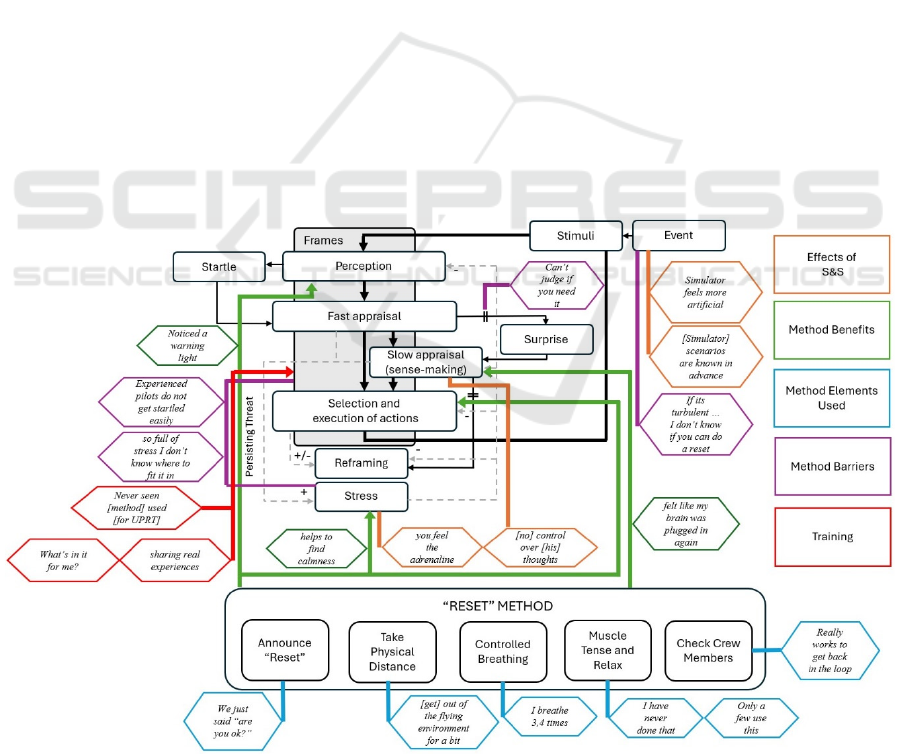

Five themes were identified. To increase the

theoretical and application clarity of the analysis,

themes were mapped onto both Landman’s S&S

model and onto the method’s procedure (Figure 1).

The Effects of S&S theme represents participants’

physical and cognitive experiences of S&S. Method

Benefits is associated with participants’ views of the

applicability and effects of the method, whilst

Method Elements Used describes how the method

was used by participants. Method Barriers represents

the perceived factors which participants reported to

hinder the methods application. Training

encompasses comments from participants that

included approaches to improving the adoption and

implementation of the method. Themes are discussed

in more detail in the following sub-sections. A

selection of participant quotes is included that best

exemplify thematic content. The 10 participants

contributions can be identified with a “P” denotation

(i.e., P1, P2…P10).

3.1 Effects of Startle and Surprise

Physical (e.g., increased heart rate) and psychological

effects (e.g., tunnel vision) of startle were reported

(Figure 1 orange boxes / paths); “you feel the

adrenaline” (P4) and “…a noose being tightened

around your neck” (P9). Some of the described

surprise experiences were associated with significant

distraction: “having [no] control over [his] thoughts

and the stress that caused”. Participant 5 described

surprise in his colleague: “he felt a bit stuck” and “I

had to pry the information out of him”.

Some respondents reported not getting easily

startled or surprised in the simulator, as non-normal

situations are expected, sometimes “scenarios are

known in advance” (P2), and the simulator feels more

“artificial” (P2). During a proficiency check “you

know what to expect” (P10) and “feeling of stress to

be a lot stronger in real life” (P1) was expected.

Figure 1: Mapping five themes (Effects of S&S, Method Benefits, Method Elements Used, Method Barriers and Training)

onto Landman’s S&S model (top) and “Reset” method (bottom). Colour coding represents thematic mapping. Selected

participant quotes included clarify mapping.

Airline Pilots’ Perceived Operational Benefit of a Startle and Surprise Management Method: A Qualitative Study

31

3.2 Benefits of Using the Reset Method

All interviewed participants were positive about the

S&S reset method (Figure 1 green boxes / paths);

Participants found it to be “effective” (P1) and that it

“helps to find calmness” (P4). Perception and

comprehension situation awareness benefits of the

method were reported. Respectively, these included:

“we noticed a warning light that we didn’t notice

before” (P6) and “…it felt like my brain was plugged

in again.” (P4) For automation surprise the

participants did not see any real benefits: “I think in

90% of the automation surprise cases…[pilots] are

fully aware but just expected something else...” (P8).

An unexpected benefit was the method’s general

stress management application. It was reported to be

useful during: “a busy day with lots of disturbances

on the ground” (P4) and a “dense fog situation at

home base” (P6).

3.3 Elements of the Method Used

This theme contained 5 subthemes representing the

steps of the method: announce reset, take physical

distance, breathe, relax muscles and check colleague

(Figure 1 blue boxes / paths). Pilots did not always

use the full method. “We didn’t call it startle and

surprise, just asked “are you ok?”” said participant 3.

The element that was reportedly least used was the

“tense/relax muscles” step - “No, I have never done

that” (P6) and “only few use the muscle tense/relax

step” (P4, instructor). The other steps were mainly

regarded positively, especially the step “check

colleague”. Corroborating Field et al. (2018), this

element is valuable in several cases where a colleague

is startled or surprised: “I asked how are you? And

then I realized this event startled him a lot…. He

thought this was all [his] fault” (P6) and “If I hadn’t

asked this question we would have remained [a] “split

cockpit” … He was still too focused on what was

going on” (P7). An additional theme about partial

application of the method was added when it became

clear that pilots did not always use the full method. "

3.4 Barrier to Method Use

Pilots stated that it can be difficult to admit one is

startled, surprised, or stressed, for fear of being seen

as incompetent (Figure 1 purple boxes / paths): “It is

a bit of a tough-guy culture” (P6). Experience, age

and level of exposure were mentioned; “experienced

pilots do not get startled that easily” (P2).

Assumptions about the application and value of the

method, hence mapping onto Frames in Landman’s

model, were evident barriers. For example,

instructors reported long-haul pilots, who are

generally older and more experienced, perceived the

value of the method to be lower than pilots flying

medium haul. Participant 1 described colleagues:

“People say hey, I’m 55, only 3 or 4 years to go [until

pension age], I don’t care [to learn new things].”

A desire to take quick action in S&S situations,

rather than employ the method, was a recurring

comment: “It feels that valuable time is lost” (P1), “I

acted immediately and forgot to think” (P7) and “you

are so full of adrenaline and stress that I don’t see

where to fit it in” (P8).

Environmental factors which interfered with the

application of the method were commented by 2

participants. In one case there was a loud noise,

making it difficult to communicate, and in the other

case there was strong turbulence at low altitude: “if

it’s so turbulent that you can’t read the instruments, I

don’t know if you can do a reset” (P6). This aspect

mapped to the Event component of Landman’s

model.

The opinion that the method was associated startle

more than surprise was voiced. With doubt

concerning its usefulness in surprise-situations

raised: “Perhaps it’s overkill for surprise” (P5) and

“perhaps it is a misconception from my side that it is

more useful in startle” (P5). This is perhaps due to the

insidious nature of surprise (that it has no clear

“trigger”) which makes it hard to recognize: “You

can’t judge if you need it because you don’t realize

it” (P3). Comments characterise the surprise

threshold element in Landman’s model, which

encompasses the large degree of inter-individual and

inter-scenario variation associated with surprise

events.

3.5 Training Improvements

Method training comments mapped onto Frames

within Landman’s model (Figure 1 red boxes / paths),

simulator training involves the establishment and

refinement of pilot schemas and scripts to be

deployed in response to given circumstances – such

as S&S. Accordingly, simulator upset recovery and

emergency descent training were voiced as being

situations where exercising the method was difficult

due to not being sufficiently addressed: “never seen it

used” (P1, instructor) and “you fly the manoeuvre and

continue to the next one” (P2).

Similarly, based on simulator experiences, the

procedures following decompression (emergency

descent) were felt to leave little room for performing

a reset: “In case of a decompression, it is fine to be

ICCAS 2024 - International Conference on Cognitive Aircraft Systems

32

startled, but you really have to go down as quickly as

possible, especially when at FL410” (P2). It is a

complicated procedure for a situation which usually

occurs suddenly, unexpectedly and with a startling

and/or surprising stimulus (such as a cabin warning

horn and/or a bang), where several memory items must

be performed and where communication is hampered

by oxygen mask use and the potential of hypoxia.

Training improvements derived from the

interviews concern better S&S recognition in oneself

and, importantly, in the other pilot. Notably, a

sentiment prevailed that the method was more

applicable to startle than surprise. Also, “sharing real

experiences” (P7) and having fellow pilots recount

the benefits of using the method in actual emergency

situations were suggested as approaches to addressing

possible machoistic culture barriers. This involves

“addressing what’s in it for me” and “providing an

incentive for behavioural change” according to

participant 10.

4 DISCUSSION

The current research presents qualitative results that

consecutively demonstrate the benefit of emerging

S&S theory and its application within the training

environment. From a theoretical viewpoint, this

research is the first to provide evidence of support for

Landman’s S&S model based on pilot experiences in

operational practice. Previous support has been based

on simulation-based research (Field et al., 2018;

Landman et al. (2020). Equally important, from an

application perspective, the research confirmed that

the S&S reset method is a much-appreciated tool for

pilots, which was perceived to reduce stress and

improve situational awareness. Furthermore, pilots

had not experienced negative effects from using the

method. The parts of the method considered to be

most useful were checking on the colleague and the

breathing technique, whilst the least used was the

tense/relax muscles technique. However, some

respondents remarked that they would prefer a shorter

method.

Some pilots indicated that they found the method

less useful for surprise. This should be interpreted

with caution, as the terms are often used

interchangeably. A survey-based follow-up research

(Vlaskamp et al., under review) did not show

significant difference between the two.

The main barrier to employing the method during

actual flight operations was the urge to engage in

immediate problem-solving. Unfortunately, problems

that are not expediently resolved will likely result in

a spiralling accumulation of stress, which in turn

impairs perceptual processes, facilitating cognitive

tunnelling, and increases the likelihood of incorrect

intuitive decisions (Field et al., 2018). Similarly,

attention to a threatening stimulus takes priority over

performing the reset method. This leads to the

hypothesis of the existence of the “startle paradox”: the

higher the stress level the more the reset method is

needed, but conversely, the more difficult the method

becomes to initiate as the overriding stress response

demotes its priority in favour of tackling the threat

“head-on”. The reported difficulty in recognizing the

effects of S&S might also be a consequence of this

effect. This reinforces the importance of the step of

checking the fellow crew member’s mental state.

Explaining the startle paradox in training should make

pilots more aware and better able to recognize and

resist the tendency to act too quickly.

In the interviews pilots reported that they find

application of the method difficult in certain

situations such as upsets and the emergency descent.

Incident reports show these to be situations with high

degrees of S&S (emergency descent (BFU, 2018).

These are also situations where memory actions must

be performed. In addition, UPRT simulator training

consists of improving upset recognition cues and

developing skills to enhance the automaticity of

recovery manoeuvres. Consequently, training

exercises are usually explained in advance,

effectively eliminating S&S effects. Restoring the

flightpath is an urgent priority and training a reflexive

response conforms to the existing recommendations

(Gillen, 2016). However, as recent loss of control

incidents show, the benefits of implementing a post-

recovery reset could be emphasized since this may

better prepared pilots for possible subsequent events

by diminishing the detrimental effects of accumulated

stress (Landman et al., 2020).

4.1 Limitations and Future Research

Limitations included the nature of its qualitative

design. For instance, hindsight bias may reduce the

retrospective “surprisingness” of a situation and

creates a tendency to turn negative feedback into

positive (Fischhoff and Beyth, 1975). This effect was

clear in several instances where participants

described negative effects of being surprised, whilst

simultaneously claiming that the reset method had not

been used “because we weren’t really surprised”.

This could be partly explained by the fact that many

reflected events will have taken place a while ago,

thus changing participants’ perception of S&S.

Finally, as is common for interview based qualitative

Airline Pilots’ Perceived Operational Benefit of a Startle and Surprise Management Method: A Qualitative Study

33

research, a small sample was included that

subsequently interferes with the generalisability of the

findings.

Future research should include a wider

investigation of the use of S&S methods within a larger

representative sample to improve understanding of

method application and benefit. A quantitative survey

could build upon this current operational validation of

the Landman model using structural evaluation

modelling (or similar methods) to add to or refine

current S&S models in order to enhance the basis for

future S&S experimental work. Research in this area is

currently in progress (Vlaskamp et al., under review).

Research examining the optimisation of S&S training,

based on pilot-informed training design, is required. In

particular, research evidencing the benefit of training

for manoeuvre specific and non-specific scenarios

would be valuable to support pilots’ judgment

regarding appropriateness of the method’s application.

For upset recovery training this is especially important,

as IATA (2019) mentions loss of control in flight

(LOC-I) as one of the main causes of aircraft accidents,

and specifically mentions startle as a factor affecting

recovery.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The effect of the “startle paradox” during pilot

training of S&S management methods should be

emphasized: the more stressful a situation is, the

stronger the urge to skip these methods. Even when

these methods feel counterintuitive, they are likely to

be useful. Methods should be trained in a variety of

difficult situations, to train appropriate timing,

especially in situations that require urgent action.

When introducing S&S management methods, the

method should be kept simple and short. For the

evaluated method this may be achieved by skipping

the “physical distance” and “tense/relax muscles”

steps.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to the pilots who volunteered their

valuable time to support this research project.

REFERENCES

Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Weate, P. (2016). Using thematic

analysis in sport and exercise research. In Routledge

handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise

(pp. 213-227). Routledge.

BFU, German Federal Bureau of Aircraft Accident

Investigation. (2018). Investigation Report BFU18-

0975-EX. http://www.aaiu.ie/sites/default/files/18-0975-

EX-efr_B737_GrostenquinVOR.pdf

Field, J. N., Boland, E. J., Van Rooij, J. M., Mohrmann, J. F.

W., & Smeltink, J. W. (2018). Startle Effect

Management. (report nr. NLR-CR-2018-242). European

Aviation Safety Agency.

Fischhoff, B., & Beyth, R. (1975). I knew it would happen:

Remembered probabilities of once—future things.

Organizational Behavior and Human Performance,

13(1), 1-16.999

Gillen, M. W. (2016). A study evaluating if targeted training

for startle effect can improve pilot reactions in handling

unexpected situations in a flight simulator. The

University of North Dakota.

Guest, G., Namey, E., & Chen, M. (2020). A simple method

to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative

research. PloS one, 15(5), e0232076.

Kochan, J., Breiter, E., & Jentsch, F. (2005). Surprise and

unexpectedness in flying: Factors and features. In 2005

International Symposium on Aviation Psychology (p.

398).

Landman, A., Groen, E. L., Van Paassen, M. M., Bronkhorst,

A. W., & Mulder, M. (2017a). Dealing with unexpected

events on the flight deck: A conceptual model of startle

and surprise. Human factors, 59(8), 1161-1172.

Landman, A., Groen, E. L., Van Paassen, M. M., Bronkhorst,

A. W., & Mulder, M. (2017b). The influence of surprise

on upset recovery performance in airline pilots. The

International Journal of Aerospace Psychology, 27(1-2),

2-14.

Landman, H.M., van Oorschot, P., van Paassen, M.M.,

Groen, E.L., Bronkhorst, A.W., Mulder, M. (2018).

Training Pilots for Unexpected Events: A Simulator

Study on the Advantage of Unpredictable and Variable

Scenarios, Human Factors, vol. 60, no. 6, p. 793-805,

2018. DOI: 10.1177/0018720818779928

Landman, A., van Middelaar, S. H., Groen, E. L., van

Paassen, M. M., Bronkhorst, A. W., & Mulder, M.

(2020). The effectiveness of a mnemonic-type startle and

surprise management procedure for pilots. The

International Journal of Aerospace Psychology, 30(3-4),

104-118.

Martin, W. L., Murray, P. S., Bates, P. R., & Lee, P. S.

(2015). Fear-potentiated startle: A review from an

aviation perspective. The International Journal of

Aviation Psychology, 25(2), 97-107.

Martin, W. L., Murray, P. S., Bates, P. R., & Lee, P. S.

(2016). A flight simulator study of the impairment effects

of startle on pilots during unexpected critical events.

Aviation Psychology and Applied Human Factors.

Rivera, J., Talone, A. B., Boesser, C. T., Jentsch, F., & Yeh,

M. (2014, September). Startle and surprise on the flight

deck: Similarities, differences, and prevalence. In

Proceedings of the human factors and ergonomics

society annual meeting (Vol. 58, No. 1, pp. 1047-1051).

Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

ICCAS 2024 - International Conference on Cognitive Aircraft Systems

34