Values and Enablers of Lessons Learned Practices: Investigating

Construction Industry Context

Jeffrey Boon Hui Yap

a

Lee Kong Chian Faculty of Engineering and Science, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR), Kajang, Selangor,

Malaysia

Keywords: Knowledge Management, Lessons Learned, Values, Enablers, Construction Industry, Project Management.

Abstract: In the realm of construction project management, the value of "lessons learned (LL)" cannot be overstated.

LL, as an important approach for effective project management and continuous improvement, is analysed in

this study, with the aim to advance the impact of LL by determining the values of LL practices and examining

the enablers that positively influence LL practices in the construction industry. A detailed literature review

has revealed nine (9) values and seven (7) enablers of LL practices relevant to the construction industry’s

context. Using a questionnaire survey involving 129 Malaysian construction professionals selected based on

non-probability techniques, the significance of the values and enablers is prioritised based on mean scores.

Findings reveal that LL practices help to avoid making similar past mistakes, optimize project performance

and engender collaborative learning in the project team. Individual-related enablers are perceived to be more

influential than organisational-related enablers in implementing LL in construction projects. Collective and

conscious efforts in fostering a learning culture are crucial to encourage the construction industry to embrace

LL practices and help individuals and organisations thrive.

1 INTRODUCTION

The construction industry acts as a catalyst for

economic growth in a developing country such as

Malaysia - increasing the country's income, work

opportunities, and infrastructure. However, the

industry is under ever-increasing pressure to deliver

projects faster, with better quality and with lower

costs. Good management practices are crucial in

achieving these demands. As Disterer (2002, p. 519)

advocates, “success of projects depends heavily on

the right combination of knowledge and experience”.

Correspondingly, Meredith et al. (2017, p.302)

accentuate, “past knowledge...should be built into

estimates of future project performance”. In

advocating knowledge representation for efficient re-

use of project memory, (Bekhti et al., 2011)

underscore the need for designers to learn from past

project experiences to deal with new design

problems. Construction companies are project-based

organisations since much of their knowledge is

generated on-site, from projects they carry out. As

such, the development of knowledge and expertise

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4332-0031

from project learning practices is critical in

construction.

Knowledge is critical for construction companies

to succeed and maximization of value through

enhancing competencies, confidence, effectiveness,

competitiveness, and sustainability. Knowledge

management (KM) processes can prevent re-

invention of the wheel, facilitate innovation; and lead

to increased agility, efficiency, flexibility, quality,

learning, better decision making, better teamwork and

supply chain integration, improved project

performance, higher client satisfaction, and

organisational growth (Eken et al., 2015; KPMG

Consulting, 2000; Yap & Lock, 2017). A recent

Malaysian study in the construction industry reveals

the most important benefits of KM are to improve

quality, enhance decision-making, raise quality,

circumvent the repeat of past mistakes and enable

knowledge exchange (Yap et al., 2022). Likewise in

Portugal, the practitioners acknowledged the most

significant aspects of KM in the management of

construction projects are associated with the

exchange of experiences between project team

38

Yap, J.

Values and Enablers of Lessons Learned Practices: Investigating Construction Industry Context.

DOI: 10.5220/0012929000003838

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 16th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2024) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 38-47

ISBN: 978-989-758-716-0; ISSN: 2184-3228

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

members, the sharing of information among

stakeholders and continuous improvements (Marinho

& Couto, 2022).KM practices can positively enhance

the effectiveness, efficiency and efficacy of project

personnel. The construction industry is project-based

but very much knowledge-intensive. Multi-

disciplinary teams (i.e. architect, engineer, quantity

surveyor and contractor) are involved and project

delivery relies heavily on previous

experience/heuristics. Thus, lessons learned (LL) in

construction projects should be captured and reused

in future projects.

Effective management of LL is vital for the

generation of project knowledge and supports

continuous learning in project-based industries such

as construction. In this vein, decision-making

processes are further enhanced by gaining insights

from the “know-what”, “know-how” and “know-

why”. The value-addedness of learning is directly

linked to project performance. This being the case, it

is necessary to determine how LL can add value to

construction project delivery and examine the

enablers that positively influence LL practices in the

construction industry. The research questions in the

present study are:

Q1: Why do we need to capture LL in construction

projects?

Q2: What are the enablers that positively influence

LL practices in construction?

2 LESSONS LEARNED (LL)

PRACTICES AND THE

CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY

LL is a critical variable for success (Kerzner, 2017) -

providing a platform for reflection, growth, and

development by extracting knowledge from past

experiences. The four dimensions of LL are: When?

What about? How know? and What is included? In

the construction industry’s context, LL is the

intellectual asset used to create value based on

previous projects and contribute to the organisation’s

learning agenda (Carrillo et al., 2013). Likewise, the

Project Management Institute’s PMBOK Guide

(Project Management Institute, 2017) underscores the

need for using existing knowledge and creating new

knowledge to achieve the project’s objectives and

contribute to organisational learning. Considering

this, the positive and negative aspects of projects are

needed to learn from past experiences, particularly in

avoiding the repetition of costly mistakes that can

jeopardise project performance and damage a

company’s reputation as well as increasing the

likelihood of attaining success that proved to be

effective and profitable. Thus, LL is very beneficial

for similar future work and improves the company’s

competitiveness, such as improved decision-making,

problem-solving and innovation. LL is particularly

vital for improving future performance (Love et al.,

2016) and for organisations to realise a competitive

edge if used properly (Hlupic et al., 2002).

Extensive knowledge is generated throughout the

construction project delivery from start to finish.

Most professionals acquire knowledge mostly

through meetings with more experienced personnel as

well as lessons learned from completed projects

(Marinho & Couto, 2022). Knowledge gained from

past projects can be leveraged to improve the

capability and productivity of construction

companies (Dave & Koskela, 2009). For example,

knowledge reuse can significantly contribute to better

expert judgment and improved time-cost

performance (Yap & Skitmore, 2020). In a Spanish

study, Forcada et al. (2013) observed the top KM

benefits being: employee experience exchange, group

work improvement and efficiency improvement.

They further explained that effective management of

project knowledge is vital in enhancing continuous

improvements from LL. For example, the project

team can better excel in project management via

sharing LL and advanced practices, which can be

transferred within and between projects (Terzieva,

2014). However, knowledge dissemination remains a

challenge and the value of LL has yet to be fully

capitalised (Debs & Hubbard, 2023).

To develop the competency of project personnel,

Yap & Shavarebi (2022) proposed sharing past

project experiences which lead to the expansion of

cognitive ability, expert judgement and better-

informed decision-making; ultimately resulting in

better project results. Tacit knowledge is developed

from experience and is hard to formalise but it is

considered to be more important than explicit

knowledge (Forcada et al., 2013; Teerajetgul &

Chareonngam, 2008). Tacit knowledge can be

captured by talking to experts and reflecting on the

LL from others. For example, using storytelling

learning to communicate LL (Duffield & Whitty,

2016). However, some construction companies fail to

recognise the value of LL and perceive LL to be

project-specific (Carrillo et al., 2013). Some

construction professionals, on the other hand, do not

want to share their problems or are not willing to learn

from other people’s mistakes (Carrillo et al., 2013).

Knowledge sharing behaviour among construction

project members are influenced by two driving

Values and Enablers of Lessons Learned Practices: Investigating Construction Industry Context

39

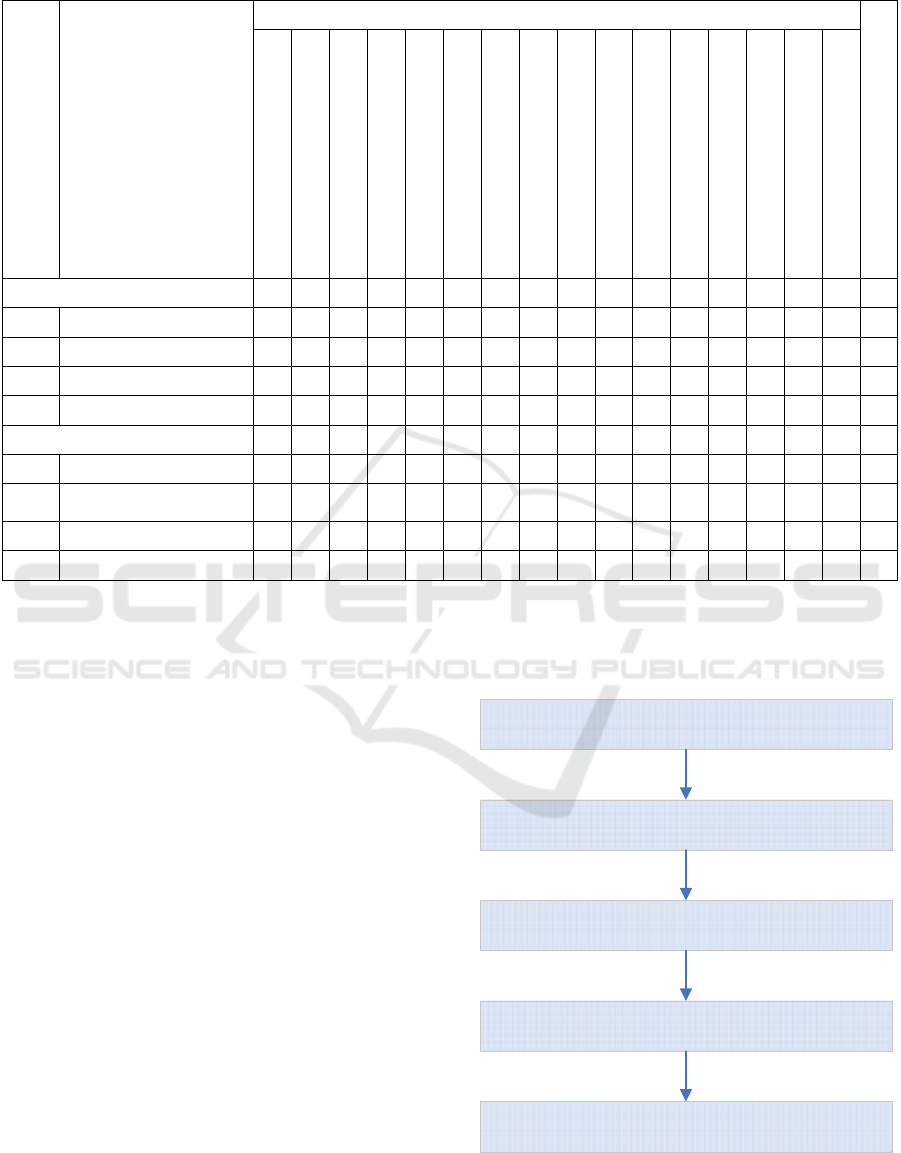

Table 1: Summary of enablers of LL practices.

Ref Enablers

Authors

Total

(Kululanga & Mccaffer, 2001)

(Levin & Cross, 2002)

(Tsai, 2002)

(MacNeil, 2003)

(Carrillo et al., 2004)

(Van Den Hooff & Ridder, 2004)

(Rego et al., 2009)

(Theriou et al., 2011)

(Javernick-Will, 2012)

(Tan et al., 2012)

(Carrillo et al., 2013)

(Duffield & Whitty, 2016)

(Longwe et al., 2015)

(Dang & Le-Hoai, 2019)

(Dang et al., 2019)

(Yang et al., 2019)

Individual

B1 Sharing culture √ √ √ √ √ √ 6

B2 Honouring of commitment √ √ √ 3

B3 Peer recognition √ √ √ √ 4

B4 Reciprocity and trust √ √ √ √ 4

Organisational

B5 Perceived value √ √ √ 3

B6

Financial/ social

motivation

√ √ √ √ √ √ 6

B7 Workplace culture √ √ √ √ √ √ √ 7

B5 Perceived value √ √ √ 3

modes, namely trust-driven and incentive-driven

(Cheng & Yin, 2024). According to the Construction

Industry Institute (CII) (2012), best practice is “a

process or method that, when executed effectively,

leads to enhanced project performance”. In the

construction project management context, best

practices or rather proven practices can be defined as

something that works well on a repetitive basis that

leads to a competitive advantage (Kerzner, 2017).

Some of the learning in projects can evolve into best

practices that can be standardized.

Table 1 presents a list of the most frequently cited

enablers of LL practices from previous literature.

There enablers are divided into individual- and

organisational-related.

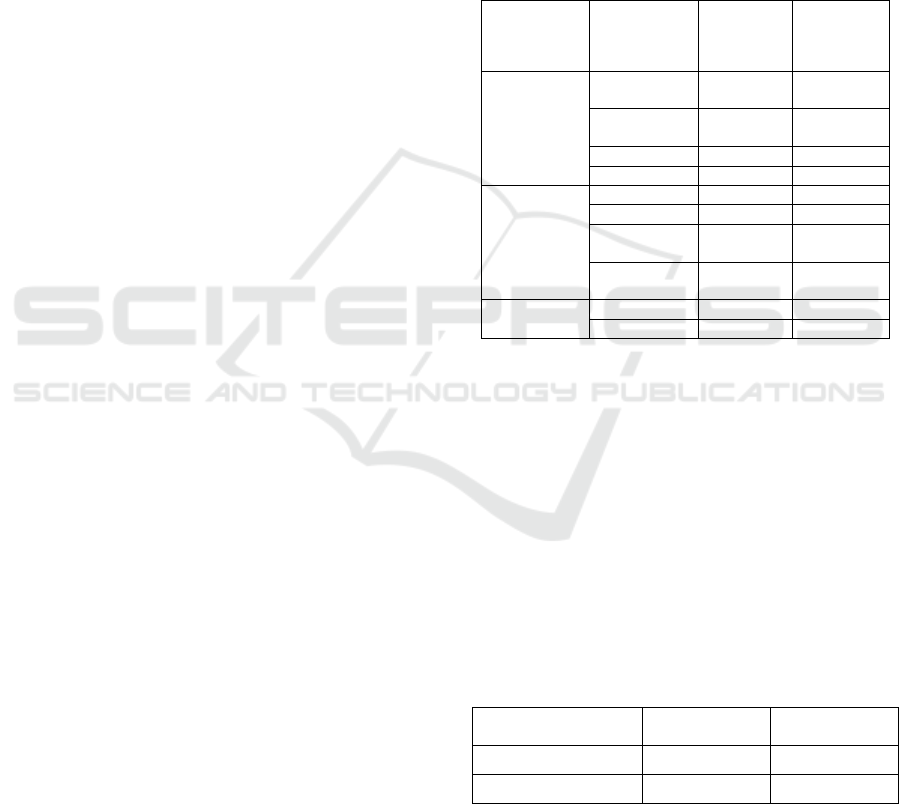

3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

A positivist paradigm employing the deductive

approach is adopted to objectively examine the

practice of capturing LL in the construction industry.

A quantitative research design with a cross-sectional

field survey was employed, as it provides an efficient

and economical means to gather feedback from a

large number of professionals currently working in

the construction industry for statistical analyses. The

methodological flowchart for the study is presented in

Figure 1.

Literature review to identify relevant values of LL and

the associated enablers

Questionnaire survey

Reliability analysis for internal consistency

Descriptive statistics to rank the variables surveyed

Most significant variables identified for discussion

Figure 1: Methodological flowchart for the study.

KMIS 2024 - 16th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

40

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences

(SPSS) version 23 was used to analyse the data

collected. The analyses were done to prioritise the

value of LL and the associated enablers/inhibitors

according to their descriptive statistics (mean scores

and standard deviations).

3.1 Questionnaire Design

The questionnaire was designed based on the

literature review and consultation with industry

subject matter experts. The questions were drafted

clearly and concisely to create easy-to-understand

materials and limited to a 15-minute completion time

to prevent survey fatigue. The questionnaire contains

three parts. Part I deals with the respondents’

demographic information, in terms of their

educational background, years of industry experience

and the type of projects involved. Part II contains the

question; Do you agree with the following value of

lessons learned in construction projects? on a five-

point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree)

to 5 (strongly agree). Part III provided a list of

enablers identified through the detailed literature

review (Table 1). For each enabler, the respondents

were requested to indicate their level of agreement on

a similar five-point Likert scale as in Part II.

3.2 Survey Respondents and

Demographics

The sampling frame consisted of professionals from

the three key parties in construction, namely clients,

consultants and contractors in Malaysia. Non-

probability techniques of purposive and convenience

with snowball sampling are used to select respondents

to yield reasonable responses. In this study, the unit

of analysis is construction professionals, as they are

the actors directly involved in project delivery. The

reason for engaging a variety of professions (i.e.

clients, consultants and contractors) was to ensure

different perspectives pertaining to LL practices in

construction are represented.

The questionnaire pilot involved 30 targeted

construction professionals to ensure clarity and

unambiguity. Following a successful pilot test, the

questionnaire remained unaltered for the main survey

whereby another 170 questionnaires were

electronically distributed. Overall, 129 valid

responses were collected after follow-up reminders,

attaining a response rate of 64.50%. The sample size

(> 100) is adequate for meaningful statistical analyses

(Roscoe, 1975; Yap & Skitmore, 2018). Additionally,

the Yamane sampling approach led to the

determination of 100 samples at a 90% confidence

level for a population size over 100,000 (Israel, 1992;

Yap et al., 2022).

Table 3 indicates the demographic profile of the

respondents, with 90 questionnaires (70%) from

respondents with at least a bachelor’s degree. Nearly

50% had more than 10 years of working experience

in construction. 57.4% of respondents are involved in

building projects. These are considered sufficient to

obtain sound judgment from qualified respondents for

this perception-based study.

Table 2: Demographic profile of respondents.

Profile Description Frequency

Percentage

(%)

Academic

qualification

Master’s

degree

33 25.6

Bachelor’s

degree

57 44.2

Diploma 37 28.7

Certificate 2 1.6

Working

experience

0 to 5 years 41 31.8

6 to 10 years 26 20.2

11 to 15

years

23 17.8

16 years and

above

39 30.2

Type of

project

Building 74 57.4

Infrastructure 55 42.6

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

4.1 Questionnaire Reliability

Table 3 summarises the α values for the two

categories of variables, viz. values and enablers of

LL, which is greater than which is higher than the

threshold of 0.70 needed to establish the internal

reliability of the scale used (Yap, Lim, et al., 2021).

This denotes that good overall reliability was

obtained on the research instrument used.

Table 3: Measurement of internal consistency.

Category

Number of

items

Cronbach’s

alpha, α

Values of LL 9 0.867

Enablers of LL 7 0.759

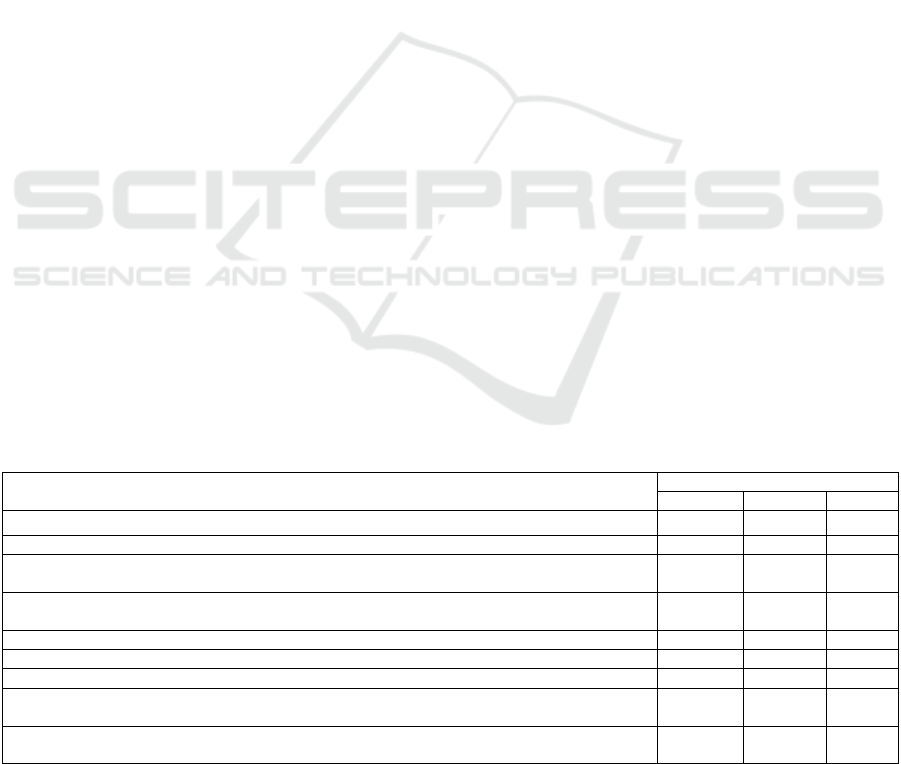

4.2 Mean Scores and Ranking LL

Values

Table 4 presents the mean scores and standard

deviations (SDs) of each value surveyed. A close

Values and Enablers of Lessons Learned Practices: Investigating Construction Industry Context

41

examination of Table 5 reveals that all 8 values have

mean scores higher than 4.0, which is regarded as

very significant in the rating scale. This implied that

the majority of the respondents either agreed or

strongly agreed with the evaluated values. The five

most significant values of capturing LL in

construction projects are:

1. A2: Avoiding the same mistakes from

happening in upcoming projects (mean =

4.519, SD = 0.574);

1. A5: Better performance or procedure by

adopting lessons learned from other projects

(mean = 4.519, SD = 0.574);

3. A9: Promote a collective environment to

attain the project team’s shared goals

through the sharing of personal experiences

(mean = 4.519, SD = 0.651);

4. A1: Ensuring good practices in previous

projects that are successful are being re-used

in upcoming projects (mean = 4512, SD =

0.626); and

5. A3: Developing new ideas or methods

through lessons learned (mean = 4.496, SD

= 0.697).

The data indicates that there is a consistent

emphasis on the value of integrating lessons learned

from previous projects across several dimensions,

with very similar mean scores suggesting a high level

of agreement among respondents. The most valuable

aspect of capturing LL for construction projects is to

avoid the recurrence of similar mistakes. The

interview participants from Yap & Skitmore’s (2020)

study specifically emphasized that “past experiences

will tell you what you can do and enrich one’s expert

judgment” and “individual needs to learn from his/her

mistakes and not repeat the same mistake twice”.

Given that project mistakes are the major contributing

factor to rework and time-cost overruns, capturing

and sharing critical LL can help construction

professionals avoid repeating the same mistakes and

reinventing the wheel in future projects. The other

highly perceived importance of LL is to enhance

productivity, efficiency and smarter working. LL is

needed to build absorptive capacity and drive towards

performance improvement in the construction

industry (Love et al., 2016).

Third, LL practices are a collaborative technique

to encourage project team members to share their

personal experiences, which will then contribute to a

collective environment in attaining shared goals.

Sharing knowledge between team members is crucial

to achieving organisational learning and collective

competence (Yap, Shavarebi and Skitmore, 2021). It

is worth noting that trust and collaboration are

significant knowledge factors for construction

projects (Teerajetgul & Charoenngam, 2006). The

fourth value of LL is related to the reuse of some best

practices from other successful projects. LL is handy

project knowledge that can be reused and employed

as best practices to increase the likelihood

of repeating project delivery success (Yap &

Shavarebi, 2022). The fifth value is making LL the

base to foster innovation and developing new

ideas/methods/solutions from long ‘trial and error’

ending with successes and failures in the construction

projects. According to Kolb & Kolb (2009), people

learn best in situations such as brainstorming sessions

that call for the generation of ideas. The recent

developments in information and communications

technology (ICT) tools have further advanced the way

people share knowledge and ideas – for improvement

and innovation (Carrillo, 2005; Yap et al., 2022).

Table 4: Ranking the values of LL.

The values of capturing LL in the construction industry context

Overall (N=129)

Mean SD Rank

A2: Avoiding the same mistakes from happening in upcoming projects. 4.519 0.574 1

A5: Better performance or procedure by adopting lessons learned from other projects. 4.519 0.574 1

A9: Promote a collective environment to attain the project team’s shared goals through the

sharing of personal experiences.

4.519 0.651 3

A1: Ensuring good practices in previous projects that are successful are being re-used in

upcoming projects.

4.512 0.626 4

A3: Developing new ideas or methods through lessons learned. 4.496 0.697 5

A4: Transforming individual knowledge to organisational knowledge by sharing lessons learned. 4.481 0.663 6

A6: Facilitate project planning (forecasting ability) using lessons learned from previous projects. 4.450 0.637 7

A7: Improvise project monitoring and control processes using lessons learned from previous

projects.

4.326 0.709 8

A8: The quality and quantity of lessons learned in the construction industry are influenced by the

size and difficulty of the project.

4.326 0.752 9

KMIS 2024 - 16th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

42

4.3 Mean Scores and Ranking LL

Enablers

Table 5 presents the enablers of LL in the

construction industry according to their significance.

All the enablers have a mean value above 4.00 and

are therefore considered relevant and very significant.

The topmost five enablers are:

1. B3: Peer recognition (mean = 4.450, SD =

0.661);

2. B1: Sharing culture (mean = 4.434, SD =

0.705);

3. B2: Honouring of commitment (mean =

4.411, SD = 0.645);

4. B4: Reciprocity and trust (mean = 4.403, SD

= 0.724); and

5. B7: Workplace culture (mean = 4.364, SD =

0.706);

Four of the five enablers are related to individual

aspects.

Table 5: Ranking of enablers.

Enablers

Overall (N=129)

Mean SD Rank

B3 4.450 0.661 1

B1 4.434 0.705 2

B2 4.411 0.645 3

B4 4.403 0.724 4

B7 4.364 0.706 5

B6 4.333 0.654 6

B5 4.248 0.729 7

4.3.1 Peer Recognition (Individual)

A construction project team involve various experts

from different skills, knowledge, experience and

professional background. All the parties work as a

team to complete a project, although there is a

hierarchical structure. Every stakeholder is allowed to

share their perception or knowledge while carrying

out a knowledge-sharing (KS) session. People like the

feeling of being recognised and thankful when they

share their knowledge, and information and

contribute to the project team, especially agreement

from seniors (MacNeil, 2003). Some people just need

a “thank you” to get affirmation from colleagues,

which in turn, helps to improve the workplace culture

(Javernick-Will, 2012).

In addition, peer recognition from colleagues,

employees or seniors encourages a person to be more

self-confident and willing to share their knowledge

with others (Rahman et al., 2018). It also encourages

self-development as well as engenders innovative and

new knowledge or ideas because they have self-

confidence and allows them to feel and look like an

expert. (Carrillo et al., 2004) believe that peer

recognition is more significant than financial

incentives because it only provides tiny opportunities

for success. According to Tan et al. (2012), peer

recognition also assists others in finding the solutions

to problems, as a result of self-confidence in sharing

knowledge with others.

4.3.2 Sharing Culture (Individual)

When individuals interact with each other in a team,

it creates a learning environment and sharing culture

in the organisation that brings benefits to the

organisation (Longwe et al., 2015). People are

actually learning by sharing tacit knowledge or their

own experience with others and hence become

explicit knowledge (Rego et al., 2009). Nonetheless,

knowledge gained from LL is difficult to transform

from tacit to explicit knowledge and be shared with

others in a team. Communication is key to sharing

knowledge. For example, breakfast or lunch

gatherings are useful platforms for exchanging

previous experiences (Fong, 2005). However, if an

individual is capable of gathering, recreating,

utilising and sharing knowledge, will bring

advantages to an organisation (MacNeil, 2003).

Moreover, knowledge sharing (KS) with competitors

by an individual is a type of coopetition. Coopetition

creates common interests between individuals and

competitors. The knowledge gained from competitors

allows individuals to benefit themselves and also

benefits an organisation. In this circumstance, an

organisation allows the development of new ideas,

skills, information, knowledge and technology from

others (Tsai, 2002).

People who contribute and share the tacit

knowledge that is stored in their brains and minds

create a sharing and learning environment (Chugh et

al., 2015; Yap et al., 2022). It encourages other

members of the organisation to share their knowledge

because everyone knows that “knowledge is power”

(Theriou et al., 2011). A workplace culture that

encourages knowledge sharing and learning allows

individuals to improve, which in turn, improves

productivity and increases the competitive advantage

of an organisation (Javernick-Will, 2012).

4.3.3 Honouring of Commitment

(Individual)

A construction project involves a lot of professionals

from different backgrounds/departments such as

architecture, engineering, cost consulting and project

management. During the management and delivery of

Values and Enablers of Lessons Learned Practices: Investigating Construction Industry Context

43

construction projects, the project team members want

to appear consistent with the project objectives and

have made their intentions to share their knowledge

explicit – they will want to live up to these intentions

and honour their commitment (Leal et al., 2017).

Once team members are involved in a problem or

issue, they would like to remain involved in it to give

advice, information, knowledge or solutions until the

problem or issue is eventually solved (Javernick-Will,

2012). This is because people like to show self-worth

and be respected by others. Another way to explain is

that people want to be compatible with others. After

their purpose of sharing knowledge is made clear, the

individuals want to stay up with these promises and

respect their pledge or even to be a leader. In

investigating knowledge exchange behaviours among

virtual communities in China, Luo et al.

(2021)observed that affective and normative

commitment can significantly influence the

knowledge contributors’ sharing intention.

Leaders play an important role in an organisation,

as a leader can inspire the team members to commit

to the project (Kululanga & Mccaffer, 2001). An

individual who wants to build a group should draft a

sanction and attend a series of meetings on

preparedness judgement or evaluation, to show that

they are well-connected, leadership and management

support. People ensure that they keep up to date and

remain active in the society. All of the above is to

ensure leaders of the teams or organisation merit their

commitment and ensure they perform their own best.

(MacNeil, 2003b).

4.3.4 Reciprocity and Trust (Individual)

The environment and relationships within a group of

people are very important, as they also influence the

success or failure of a project. To facilitate LL

practices in the construction industry, people must

learn to reciprocate (Dang et al., 2019). Some people

are more willing to share knowledge with those

people who helped and supported them before when

those people faced some issues or problems. People

will think that it is the way to pay back as they helped

them before. It is a mutual benefit relationship

(Javernick-Will, 2012). This can be understood by the

adage that “people treat you like the way you treat

them”. It is a two-way relationship.

The norm of reciprocity also indirectly creates

trust relationships among people. People are also

more willing to share knowledge when trust exists.

Trust is also a two-way relationship same as

reciprocity, to tighten the relationship within a team

(Rego et al., 2009). Thus, knowledge exchange is

better and faster if people in the organisation trust

each other. When trust exists, people provide and

share useful knowledge willingly. Therefore, people

are also likely to hear, consume and learn the

knowledge shared by other people (Levin & Cross,

2002). It reduces conflicts between the people in the

organisation by the existence of reciprocity and trust.

4.3.5 Workplace Culture (Organisational)

In a successful KM system, organisational culture is

the most crucial facilitating factor. An organisation

should share their vision and mission with all the

employees or team members (Yang et al., 2019).

“Work as a team is better than one”, because

teamwork increases collaboration and allows

brainstorming to develop or create more ideas and

thus improve productivity (Theriou et al., 2011).

When every party have the same vision and the same

target as the organisation, they are more likely to

contribute and complete the project efficiently and

effectively (Kululanga & Mccaffer, 2001). The

culture of the workplace highly affects a person’s

behaviour and attitude, therefore affecting the

performance of an organisation (Rego et al., 2009b).

A person who works in a positive workplace culture

will be influenced by the environment of the

organisation and participate in any activities actively.

When working in a negative workplace culture, the

person will have the same feelings and will not want

to contribute to the organisation (Tan et al., 2012).

For example, a student would perform better in a

good class, because they are studying under positive

influence, although the student does not have a good

basic.

Furthermore, practitioner shares their visions,

committed leadership and reward creativity and

innovation depending on the culture of the workplace

(Dang et al., 2019). Therefore, a workplace culture

influences the success of LL practices and also affects

the success of an organisation (Duffield & Whitty,

2016).

5 CONCLUDING REMARKS

From a detailed literature review nine (9) values and

seven (7) enablers of LL practices in the construction

industry were identified. The opinions of construction

professionals currently working in Malaysia were

obtained through a cross-sectional self-administered

questionnaire survey. The underlying aim of ranking

the values and enablers is towards recognizing and

embracing the importance of LL practices in the

KMIS 2024 - 16th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

44

complex construction environment to increase the

chances of project success as well as cultivate a

culture of learning and improvement that can benefit

construction organisations in all aspects of their

operations. Findings reveal that avoiding the same

mistakes from happening in upcoming projects, better

performance or procedure by adopting lessons

learned from other projects and promoting a

collective environment to attain the project team’s

shared goals through the sharing of personal

experiences are the leading values of performing LL.

Construction organisations that prioritise LL

practices not only can take advantage of lessons from

previous successes and failures but also enhance

project outcomes with improved ability to plan,

schedule and estimate their future projects. The most

influential enablers are peer recognition, sharing

culture and honouring of commitment. Collective and

conscious efforts in fostering a learning culture are

crucial to encourage the construction industry to

embrace LL practices – help individuals and

organisations thrive.

While the study makes several contributions to

LL practices in construction project management, it

is limited by the single data collection method using

field survey possibly causing mono-method bias.

Nevertheless, this is substantiated by triangulating the

findings by cross-referencing the research literature

for theoretical validation. Although the use of a self-

completion questionnaire form is widely used to

gather quantitative data from a large and diverse

sample for statistical analyses, it does not allow

researchers to probe or clarify participants’ responses.

An interpretative approach using in-depth interviews

and/or case studies could be further employed to

collect rich real-world project experiences from

construction professionals, as well as to validate the

statistical results. The rating of the values and

enablers of LL practices on a five-point Likert scale

may not be completely reliable as different

respondents may perceive the scale differently when

they attach their interpretation of the different scale

points. It is worth noting that the Likert scale is

commonly used to measure people’s opinions,

perceptions and attitudes in behavioural sciences and

construction project management studies. Further

studies would benefit by investigating some of the

formal and informal best practices for capturing LL at

various phases of construction project delivery,

particularly on how emerging digital technologies

have revolutionized KM practices in the construction

context.

REFERENCES

Bekhti, S., Matta, N., & Djaiz, C. (2011). Knowledge

representation for an efficient re-use of project

memory. Applied Computing and Informatics, 9(2),

119–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aci.2011.05.004

Carrillo, P. (2005). Lessons learned practices in the

engineering, procurement and construction sector.

Engineering, Construction and Architectural

Management, 12(3), 236–250.

Carrillo, P., Robinson, H., Al-Ghassani, A., & Anumba, C.

(2004). Knowledge management in UK construction:

Strategies, resources and barriers. Project Management

Journal, 35(2), 46–56.

Carrillo, P., Ruikar, K., & Fuller, P. (2013). When will we

learn? Improving lessons learned practice in

construction. International Journal of Project

Management, 31(4), 567–578.

Cheng, F., & Yin, Y. (2024). Organizational antecedents

and multiple paths of knowledge-sharing behavior of

construction project members: evidence from Chinese

construction enterprises. Engineering, Construction

and Architectural Management, 31(3), 957–975.

https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-07-2022-0614

Chugh, R., Wibowo, S., & Grandhi, S. (2015). Mandating

the transfer of tacit knowledge in Australian

universities. Journal of Organizational Knowledge

Management, 2015, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.5171/2015

Construction Industry Institute. (2012). CII best practices

guide: Improving project performance. In Construction

Industry Institute.

Dang, C. N., & Le-Hoai, L. (2019). Relating knowledge

creation factors to construction organizations’

effectiveness: Empirical study. Journal of Engineering,

Design and Technology, 17(3), 515–536.

Dang, C. N., Le-Hoai, L., & Peansupap, V. (2019). Linking

knowledge enabling factors to organizational

performance: Empirical study of project-based firms.

International Journal of Construction Management.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2019.1637097

Dave, B., & Koskela, L. (2009). Collaborative knowledge

management: A construction case study. Automation in

Construction, 18(7), 894–902.

Debs, L., & Hubbard, B. (2023). Gathering and

disseminating lessons learned in construction

companies to support knowledge management.

Construction Economics and Building, 23(1/2), 56–76.

Disterer, G. (2002). Management of project knowledge and

experiences. Journal of Knowledge Management, 6(5),

512–520.

Duffield, S. M., & Whitty, S. J. (2016). Developing a

systemic lessons learned knowledge model for

organisational learning through projects. International

Journal of Project Management, 33(2), 1280–1293.

Duffield, S., & Whitty, S. J. (2016). How to apply the

systemic lessons learned knowledge model to wire an

organisation for the capability of storytelling.

International Journal of Project Management, 34(3),

429–443.

Values and Enablers of Lessons Learned Practices: Investigating Construction Industry Context

45

Eken, G., Bilgin, G., Dikmen, I., & Birgonul, M. T. (2015).

A lessons learned database structure for construction

companies. Procedia Engineering, 123, 135–144.

Fong, P. S. (2005). Building a knowledge sharing culture in

construction project teams. In C. J. Anumba, C. Egbu,

& P. M. Carrillo (Eds.), Knowledge Management in

Construction (pp. 195–212). Wiley-Blackwell.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283256545

Forcada, N., Fuertes, A., Gangolells, M., Casals, M., &

MacArulla, M. (2013). Knowledge management

perceptions in construction and design companies.

Automation in Construction, 29(January), 83–91.

Hlupic, V., Pouloudi, A., & Rzevski, G. (2002). Towards

an integrated approach to knowledge management:

“Hard”, “soft” and “abstract” issues. Knowledge and

Process Management, 9(2), 90–102.

Israel, G. D. (1992). Determining sample size. University of

Florida, IFAS Extension, PE0D6(April 2009), 1–5.

https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/PD/PD00600.pdf

Javernick-Will, A. (2012). Motivating knowledge sharing

in engineering and construction organizations: Power

of social motivations. Journal of Management in

Engineering, 28(2), 93–202.

Kerzner, H. R. (2017). Project management: A systems

approach to planning, scheduling, and controlling.

(12th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2009). Experiential learning

theory: A Dynamic, holistic approach to management

learning, education and development. In S. Armstrong

& C. Fukami (Eds.), The Sage handbook of

management learning, education and development.

KPMG Consulting. (2000). Knowledge management:

Research report 2000.

Kululanga, G. K., & Mccaffer, R. (2001). Measuring

knowledge management for construction organizations.

Engineering, Construction and Architectural

Management, 8(5–6), 346–354.

Leal, C., Cunha, S., & Couto, I. (2017). Knowledge sharing

at the construction sector - Facilitators and inhibitors.

Procedia Computer Science, 121, 998–1005.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2017.11.129

Levin, D. Z., & Cross, R. (2002). The strength of weak ties

you can trust: The mediating role of trust in effective

knowledge transfer. Management Science, 50(11),

1477–1490.

Longwe, T., Lord, W., & Carrillo, P. (2015). The impact of

employee experience in uptake of company

collaborative tool. Proceedings of the 31st Annual

ARCOM Conference Lincoln, UK, 621–629.

Love, P. E. D., Teo, P., Davidson, M., Cumming, S., &

Morrison, J. (2016). Building absorptive capacity in an

alliance: Process improvement through lessons learned.

International Journal of Project Management, 34(7),

1123–1137.

Luo, C., Lan, Y., (Robert) Luo, X., & Li, H. (2021). The

effect of commitment on knowledge sharing: An

empirical study of virtual communities. Technological

Forecasting and Social Change, 163. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120438

MacNeil, C. M. (2003). Line managers: Facilitators of

knowledge sharing in teams. Employee Relations,

25(3), 294–307.

Marinho, A. J. C., & Couto, J. (2022). Contribution to

improvement of knowledge management in the

construction industry - Stakeholders’ perspective on

implementation in the largest construction companies.

Cogent Engineering, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/

23311916.2022.2132652

Meredith, J. R., Shafer, S. M., & Mantel, S. J. (2017).

Project management: A managerial approach (10th

ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Project Management Institute. (2017). A guide to the

project management body of knowledge (PMBOK

Guide) (6th ed.). Project Management Institute, Inc.

Rahman, M. S., Mannan, M., Hossain, M. A., Zaman, M.

H., & Hassan, H. (2018). Tacit knowledge-sharing

behavior among the academic staff: Trust, self-efficacy,

motivation and Big Five personality traits embedded

model. International Journal of Educational

Management, 32(5), 761–782. https://doi.org/10.1108/

IJEM-08-2017-0193

Rego, A., Pinho, I., Pedrosa, J., & Pina E. Cunha, M.

(2009). Barriers and facilitators to knowledge

management in university research centers. Journal of

the Iberoamerican Academy of Management, 7(1), 33–

47.

Roscoe, J. T. (1975). Fundamental research statistics for

the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Holt, Rinehart and

Winston.

Tan, H. C., Carrillo, P. M., & Anumba, C. J. (2012). Case

study of knowledge management implementation in a

medium-sized construction sector firm. Journal of

Management in Engineering, 28(3), 338–347.

https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.00001

09

Teerajetgul, W., & Chareonngam, C. (2008). Tacit

knowledge utilization in Thai construction projects.

Journal of Knowledge Management, 12(1), 164–174.

Teerajetgul, W., & Charoenngam, C. (2006). Factors

inducing knowledge creation: Empirical evidence from

Thai construction projects. Engineering, Construction

and Architectural Management, 13(6), 584–599.

Terzieva, M. (2014). Project knowledge management: How

organizations learn from experience. Procedia

Technology, 16

, 1086–1095.

Theriou, N., Maditinos, D., & Theriou, G. (2011).

Knowledge management enabler factors and firm

performance: An empirical research of the Greek

medium and large firms. European Research Studies

Journal, 14(2), 97–134.

Tsai, W. (2002a). Social structure of “coopetition” within a

multiunit organization: Coordination, competition, and

intraorganizational knowledge sharing. Organization

Science, 13(2), 179–190.

Tsai, W. (2002b). Social structure of “coopetition” within a

multiunit organization: Coordination, competition, and

intraorganizational knowledge sharing. Organization

Science, 13(2), 179–190.

KMIS 2024 - 16th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

46

Van Den Hooff, B., & Ridder, J. A. (2004). Knowledge

sharing in context: The influence of organizational

commitment, communication climate and CMC use on

knowledge sharing. Journal of Knowledge

Management, 8(6), 117–130.

Yang, Y., Brosch, G., Yang, B., & Cadden, T. (2019).

Dissemination and communication of lessons learned

for a project-based business with the application of

information technology: a case study with Siemens.

Production Planning & Control. https://doi.org/

10.1080/09537287.2019.1630682

Yap, J. B. H., Lim, B. L., & Skitmore, M. (2022).

Capitalising knowledge management ( KM ) for

improving project delivery in construction. Ain Shams

Engineering Journal, 13(6), 101790. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.asej.2022.101790

Yap, J. B. H., Lim, B. L., Skitmore, M., & Gray, J. (2021).

Criticality of project knowledge and experience in the

delivery of construction projects. Journal of

Engineering, Design and Technology. https://doi.org/

10.1108/JEDT-10-2020-0413

Yap, J. B. H., & Lock, A. (2017). Analysing the benefits,

techniques, tools and challenges of knowledge

management practices in the Malaysian construction

SMEs. Journal of Engineering, Design and

Technology, 15(6), 803–825.

Yap, J. B. H., & Shavarebi, K. (2022). Enhancing project

delivery performances in construction through

experiential learning and personal constructs:

competency development. International Journal of

Construction Management, 22(3), 436–452.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2019.1629864

Yap, J. B. H., Shavarebi, K., & Skitmore, M. (2021).

Capturing and reusing knowledge: analysing the what ,

how and why for construction planning and control.

Production Planning & Control, 32(11), 875–888.

Yap, J. B. H., & Skitmore, M. (2018). Investigating design

changes in Malaysian building projects. Architectural

Engineering and Design Management, 14(3), 218–238.

Yap, J. B. H., & Skitmore, M. (2020). Ameliorating time

and cost control with project learning and

communication management Leveraging on reusable

knowledge assets. International Journal of Managing

Projects in Business, 13(4), 767–792.

Values and Enablers of Lessons Learned Practices: Investigating Construction Industry Context

47