Design and Evaluation of Microteaching: Emergent Learning for

Acquiring Classroom Management Skill in Teacher Education

Dai Sakuma

1a

, Keitaro Tokutake

2b

and Masao Murota

3c

1

Faculty of Teacher Education, Shumei University, 1-1 Daigaku-cho, Yachiyo-shi, Chiba, Japan

2

School of Environment and Society, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Japan, 2-12-1, Ookayama, Meguro-ku, Tokyo, Japan

3

Institute for Liberal Arts, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Japan, 2-12-1, Ookayama, Meguro-ku, Tokyo, Japan

Keywords: Emergent Learning, Classroom Management, Microteaching, Teacher’s Knowledge, Adaptive Teaching.

Abstract: Schools in countries struggling with academic achievement gaps need to improve the teaching and support

skills for students who facilitate classes in these gaps. This study focused on methods for acquiring complex

classroom management skills for pre-service teachers. The aim of the study was to design and validate a

method for teacher candidates to learn these behaviors. To achieve this, microteaching sessions in which

unexpected behaviors occur were designed and carried out. A video recording of the microteaching was used

in the evaluation experiment. Evaluators were five expert teachers in Japan. Statistical tests using the results

of the questionnaire responses revealed that the simulated situations by student roles were close to actual

situations with real students. It was also confirmed that the teaching candidates experienced situations that

required various management behaviors. These results indicate that the microteaching sessions designed by

the authors are useful as a method for emergent learning to achieve management skills in the classroom to

control unexpected behaviors.

1 INTRODUCTION

Many countries have recognized inclusive education,

but its definitions and implementations vary widely

(Haug, 2017). In countries with large achievement

gaps, students who struggle to follow teachers’

instructions are often labeled as exhibiting

“unexpected behavior”.

Emergent learning, where preservice teachers

respond flexibly to students’ needs, is crucial for

effective classroom management and enhances

educational quality. It requires not only planned

lessons but also improvisation to engage students.

Microteaching has been a method to train

prospective teachers by allowing them to practice

teaching skills in a controlled environment (Allen

1966; Sakamoto 1981; Sakuma et al. 2019). This

technique helps improve skills such as attention

management, questioning, and class control (Gower

et al., 1995; Capel et al., 1998; Kilic, 2010). The

Learner-Centred Microteaching (LCMT) model

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-3638-8229

b

https://orcid.org/0009-0002-1099-5518

c

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-9727-3096

involves decision-making, planning, application,

evaluation, and reflection, and is used to help teachers

learn emergent management skills (Kilic, 2010).

However, there are limited examples of emergent

learning in microteaching, especially regarding

management procedures and behaviors for

unexpected behavior. Microteaching can teach

emergent behaviors that prevent unexpected

classroom disruptions. Research on teachers’

decision-making and information processing is

important in this context (Pittman, 1985; Yoshizaki,

1988).

To design learning in a simulated classroom, it’s

important to consider teachers’ information

processing and decision-making models. Pittman

(1985) identified three strategies teachers use for

management: training, corrective, and push-in.

Yoshizaki (1988) viewed teachers as information

processors who explore routines and adapt to

classroom situations. Some studies have attempted to

approximate the environment of microteaching to that

222

Sakuma, D., Tokutake, K. and Murota, M.

Design and Evaluation of Microteaching: Emergent Learning for Acquiring Classroom Management Skill in Teacher Education.

DOI: 10.5220/0012942200003838

In Proceedings of the 16th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2024) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 222-229

ISBN: 978-989-758-716-0; ISSN: 2184-3228

Copyright © 2024 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

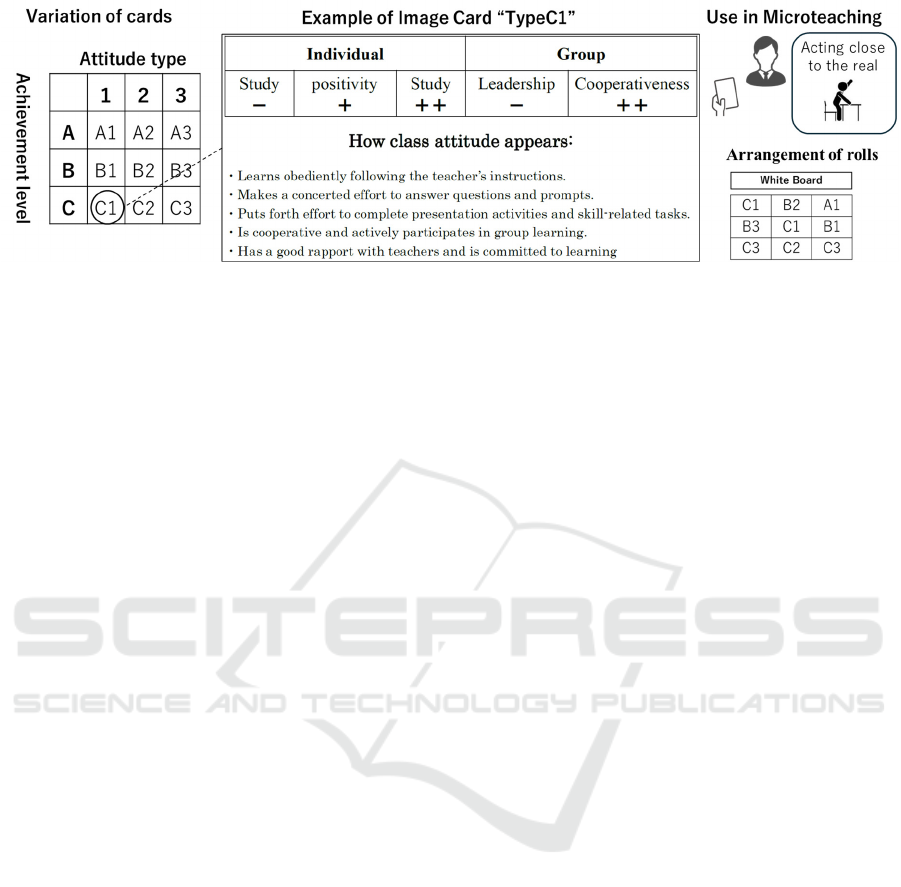

Figure 1: Overview of Microteaching Design and Simulation.

of an actual class, enhancing its effectiveness.

Sakuma et al. (2019) developed image cards to assist

pupil roles’ acts in microteaching for this purpose.

This study provides insights into the design and

implementation of microteaching sessions that

incorporate unexpected student behaviors.

2 PURPOSE OF STUDY

2.1 Design of Microteaching

In this study, we developed and evaluated a

microteaching method for prospective teachers to

manage unexpected student behaviors in classroom

settings using Image-cards (Sakuma et al. 2019).

In the microteaching which we designed, teacher-

role extracts the situations of attitudes and behaviors

of the student-role from the classroom situation and

recognizes and discriminates between expected and

non-expected behaviors. The teacher roles

experienced situations by the student role’s behaviors

include delay in learning, interruption of learning,

withdrawal from learning, disturbance to others and

disturbance to the teacher. These categories were

developed by classifying examples of attitudes and

behaviors from Sakuma et al. (2019) image cards. It

is assumed that, depending on the perceived

attitude/behavior situation. The teacher roles then

recognise the discrepancies between the lesson plan

and the actual situation and the factors.

In addition, the teacher role has a learning

opportunity to invoke or create management actions

to resolve the discrepancy between the plan and the

actual situation. Through this learning opportunity,

the teacher role learns management behaviors to

control the unexpected behavior.

Thus, we assume emergent learning, in which the

number of perceived unexpected behaviors, including

disruptive behaviors to the lesson, decision-making

activities related to management are activated, and

the teacher role invokes management behaviors and

creates alternative solutions.

Figure 1 shows that the overview of the student

image cards used in designing the microteaching

(Sakuma et al. 2019). They consisted of three types

based on the degree of 'learning achievement' (A:

high - C: low) and three types based on the degree of

'difficulty in following instruction' (1: easy to follow

- 3: difficult to follow): A1, A2, A3, B1, B2, B3, C1,

C2, C3. Figure 1 shows the types of image cards used

and the seating arrangements of the student roles

when a microteaching is conducted with nine student

roles.

The microteaching which we designed has system

to make it easy for situations to occur in which student

roles in C1, C2, and C3 are more than half of the total

number of students in the class, and in which they

become noisy and cannot follow instructions.

Specifically, the roles and their number were set up

with reference to the characteristics of a disrupted

class in which more than half of the student roles are

dissatisfied with class life or are unable to comply

with class rules, and in which the roles of student C1,

C2 and C3 are more than half of the total number of

student roles in the class, which can lead to a situation

of withdrawal from class and a situation of general

noisiness and lack of following instructions.

Additionally, place student roles who are difficult

to reach for instruction in seats that are closest to the

teacher and within the teacher’s sight. The student

roles whose guidance is easy to follow are put in the

role of supporting the learning of the student roles.

Therefore, to create unexpected behavior, C3 was

placed in the seat farthest away from the teacher,

contrary to the considerations. In addition, A1 was

placed in the seat farthest away from C3.

Design and Evaluation of Microteaching: Emergent Learning for Acquiring Classroom Management Skill in Teacher Education

223

Table 1: Examples of situations which confirmed in Microteaching authors designed.

2.2 Application

Microteaching designs were incorporated into a

practice-based class for second-year university

students aspiring to become primary school teachers.

The implementation date was December 12, 2015.

The participants in each group consisted of one

teacher, nine students, and an extra observer. The

microteaching took approximately 30 minutes. The

scope of study covered the third grade of primary

schools. The learning objectives for both Design1 and

Design2 were "to understand how to add and subtract

decimals to and from one decimal place, and to be

able to perform these calculations".

The learning task for the class, designed by the

teacher role in Design1, was to line up A4-sized

sheets of colored paper, which were regarded as 1,

with thin sheets of colored paper, which were

regarded as 0.1, and ask students to think about how

many 0.1s could be placed in the sheet ”1”. One set

of these materials was prepared for each group of

three. The lesson learning task designed by the

teacher of Design2 was to ask the students to think

about how many 0.5L and 0.3L together would be,

through the juxtaposition of 'colored paper with a

picture of two beakers' and 'thin colored paper that is

0.1L.

The learning task for the lesson designed by the

Design1 teacher was to line up A4-sized colored

paper regarded as 1 with thin colored paper regarded

as 0.1 and ask the students to think about how many

0.1s could be put into 1. One set of these materials

was prepared for each group of three.

The learning task of the lesson designed by the

teacher in Design2 is to have the students think about

how many pieces of paper 0.5L and 0.3L add up to

through the arrangement of "colored paper with a

picture of two beakers" and "thin colored paper that

is considered to be 0.1L".

In addition, the teacher role of Design1 facilitated

the class with the student roles sitting on the floor,

without using a desk. On the other hand, the teacher

of the Design2 conducted the class with the student

roles sitting on chairs, in the seating order shown in

Figure.1 (right side). The reasons for the differences

in the teaching materials prepared by the teachers of

the Design1 discussed below. The characteristics of

the students played by the pre-service teachers in the

microteaching were known from the lesson design

stage for Design1. Therefore, the teacher had the

original idea of having the students sit on the floor for

the class and tried to attract the students' interest. In

addition, it can be said that the teacher tried to avoid

unexpected behavior by giving the student a specific

task to do in groups of three, namely 'laying out the

cards (0.1) on A4 paper (1)', so that the student role

could concentrate on their learning.

2.3 Management Behavior

Hereafter, the unexpected behavior that occurred in

the microteaching designed in this study will be

Design2Design1

SituationNo.SituationNo.

Sleeping situation from the beginning of the class

1

Situations where instructions are not followed and the

class is held up

1

Situations where they turn their back

2

Messing with other children

2

Playing with stationery or misbehaving

3

Playing with stationery or teaching aids

3

Hitting another friend to wake them up

4

Throwing things

4

Messing with a friend

5

Threatening or provoking other children

5

Dropping things

6

Going outside without permission

6

Walking around situation

7

Inviting other children to play

7

Going outside

8

Shouting or shouting

8

Hitting another friend to wake them up

9

Playing with stationery or teaching aids

9

Turns his/her back

10

Pointing out minor mistakes by the teacher

10

A situation where the child starts reading a book

11

Situations where children start to play

11

Situations where the whole place becomes noisy

12

Talking about topics unrelated to the lesson

12

Situations where the child does not want to cooperate in

a cooperative learning situation

13

Drawing on the blackboard

13

Throwing erasers or scraps of paper

14

Singing a song when bored with learning

14

A situation in which the whole class becomes

increasingly noisy while writing on the board

15

Situations where the pupil's gaze is not looking in the

direction of anyone other than the teacher

15

A situation in which greetings are not coordinated

16

KMIS 2024 - 16th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

224

referred to as the simulated situation. The events and

situations that occur in the actual classroom are

referred to as actual situations.

Examples of simulated situations that occurred in

the microteaching designed by the authors are shown,

based on a series of utterances obtained by

transcription from the video recordings. For reasons

of space limitation, approximately one minute of each

lesson is shown for both Design1 and Design2. The

simulated situations are single underlined. The

management behaviors created by the respective

teacher roles are underlined with a chain line.

The following are the classroom situations

observed at the beginning of the Design2 practice and

the simulated situations.

[Teacher]: Good morning, everyone, I'd like to start

the first period, Tom (C1), please wake up.

[C3 role]: wake up - Tom (C1 role)!

[Any roles]: 'Wake up, first period is starting'.

[Teacher]: Tom, you must be sleepy.

[C1 role]:I want to sleep, and going to home.

[Teacher]: George, what are you doing? Well, It's

time to start first period, Bob, what are

you doing?

[C3 role]: (turning back, looking restless)

[Teacher]: Bob, I'm going to start, but I thought I'd

check one rule, Bob, face forward.

[C3 role]: eh.

[Teacher]: Look forward, yes, please. And everyone,

I'm going to go over the rules that we've

been going over all this time, and if, while

we're teaching, you get an itch and you

feel like you want to stand up, please raise

your hand immediately. The reason is that

if you stand up, the teacher will be worried,

so if you make a signal before that, you

can do it, so do you remember the rules?

Bob, are you okay?

From the utterance, it can be said that the teacher

role created the management behavior of 'taking up

stationery'. Similarly, it can be said that the teacher

role of the Design2 implemented the management

behavior of 'checking the rules of the class during the

lesson.

2.4 Teacher Role's Reflections

Immediately after the practice of the microteaching,

the teacher roles were asked to reflect on their own

classes. The parts of transcripts of their utterances are

shown below. The transcripts of the teacher role of

Design2’s utterances are shown below.

[Teacher]: Well, for the time being, since I was in the

lower ranks...[omission]...my goal was to

do 1.0, 1 and up to what we did today on

the assumption that I couldn't go to the

problem areas, but it still took a lot of time

to deal with the student roles who were

doing something or not doing something. I

realized that it really takes a lot of time to

deal with every student role who is doing

something or not doing something, or who

is standing up and walking around, and I

thought I still don't know where to switch

and ignore them. ...[omission]...I also

thought that it was very difficult to know

where to switch from caution to scolding,

and I was thinking about this as I tried to

deal with the student roles who were

moving around. I was also thinking about

how to deal with the student roles who

didn't write a lot, and there were a lot of

student roles who didn't write a lot this time,

and whether to adapt to the role of the

student roles who wrote a lot or the

majority who didn't write a lot, so I adapted

to that role.

The teacher role of the Design2 was searching for

a teaching method that could achieve the goal in a

simulated situation where unexpected student role

behavior was observed. As a result, it can be said that,

as the authors intended, they created their own

management behavior of 'changing the form of the

learning activity' during the lesson.

3 EXPERT ASSESSMENT

3.1 Method of Evaluation

An Expert evaluation experiment was conducted on

the environment and learning of a microteaching

designed by the authors. The following three

evaluations of the simulated classroom environment

were obtained.

・Whether the simulated situation as a whole is close

to the actual situation

・Whether each simulated situation is close to the

actual situation

・Whether each simulated situation is an opportunity

to learn management behaviors

Is it close to the individual situation that causes it

(assessment of similarity)?

・Whether it is an opportunity for the teacher role to

learn management behaviors (evaluation as a

learning opportunity).

Design and Evaluation of Microteaching: Emergent Learning for Acquiring Classroom Management Skill in Teacher Education

225

For evaluating learning effects, the teacher roles

experienced creating management strategies that

mitigate unexpected behaviors during microteaching

sessions

The implementation periods were 16, 23, and 30

April and 9 and 14 May 2016. On each date, one

evaluator was invited to the laboratory to carry out the

evaluation experiment. The total experimental time

spent per person was around 120 minutes. Evaluators

were expert teachers with an average of 29.8 years of

experience (S.D: 10.8 years).

The procedure for the evaluation experiment is as

follows.

1. Experimental teaching

2. Viewing of video recordings of the microteaching

and interviews

3. Evaluation of the simulated situation from five

perspectives through a questionnaire survey.

For (1), the purpose and flow of the experiment were

explained to the evaluators. For (2), the evaluators

were asked to randomly select and watch one of the

two designs and one of the designed children that

were practiced in this study. During the viewing of

the video, the stop-and-motion method of Fujioka

(1991) was used to obtain the evaluators’ learning of

the microteachings designed by the authors and their

evaluative utterances of the situations that the

students’ roles caused.

The following questions were set for the class

evaluation and semi-structured interviews were

conducted.

・What teacher skills and knowledge were learned

through experiencing the focused event?

The stop-and-motion method of Fujioka (1991)

was used when the evaluator spoke about the

simulated situation, to implement the same format as

in a classroom review meeting in a school setting.

In addition, the evaluators were asked to watch a

simulated situation randomly selected by the authors

beforehand, and to rate whether the simulated

situation was close to the actual situation or not using

a five-point scale (1: does not apply - 5: applies). At

the same time, using Asada and Sako's (1991)

classification of eight types of management behaviors,

the teachers were asked to choose which of the

simulated situations they were asked to watch

corresponded to a learning opportunity for creating

management behavior. Multiple answers were

allowed. The eight options were A. Inserting teaching

materials, B. Changing the form of children's

activities, C. Changing the order of nomination, D.

Changing the sequence of questions, E. Changing the

nomination-response rule, F. Changi ng the form of

communication, G. Changing the response method,

and H. Attention and instruction.

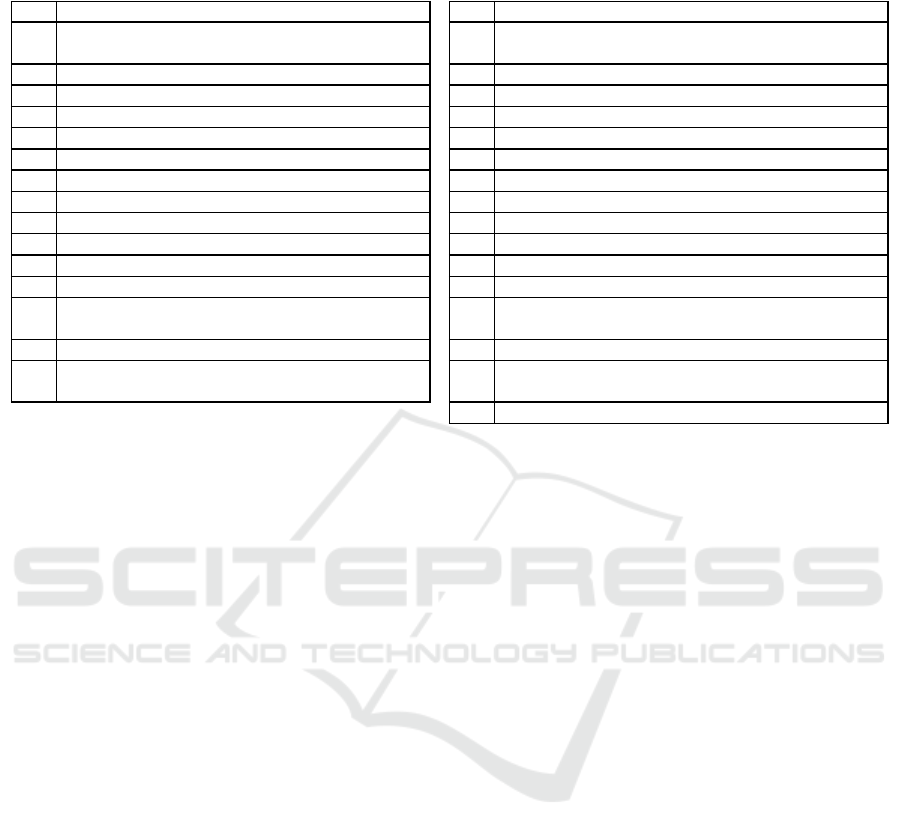

Table 1 shows the extracted simulated situations.

Regarding (3), the authors clarified from five

perspectives whether the situations in the student role

that occurred within the microteaching designed by

the authors were closer to the actual classes compared

to the traditional microteaching.

In the present study, this questionnaire item was

also used, and the evaluators were asked to answer the

questions using a five-point scale (1: does not apply -

5: applies). The five question items used by Sakuma

et al. (2019) were:

(i). Diverse situations,

(ii). Individual child situations

(iii). Overall child situations

(iv). Impact and change on other children

(v). Events that test the trust relationship with the

teacher.

3.2 Results of Analysis

To determine whether the five simulated situations -

(1) various situations, (2) individual child situations,

(3) overall child situations, (4) effects and changes on

other children, and (5) events that test the trust

relationship with the teacher - approximated the

actual situations, a one-sample t-test was conducted

with the population mean considered to be 3. The

results of the analysis showed a significant trend and

a significant difference in the results of all the

responses of the rater groups. The test results are

shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Results of t-tests for similarity (N=5).

Design2Design1

Degree of approximationDegree of approximation

P-valueS.D.MeanP-valueS.D.Mean

Quetion

0.024 *0.554.600.032 *0.554.60(ⅰ) Diverse situations

0.003 **0.454.200.002 **0.844.20(ⅱ) Individual pupil situation

0.002 **0.454.200.004 **0.554.40(ⅲ)Overall situation of the pupil

0.003 **0.454.200.004 **0.894.40(ⅳ)Impact and change on other pupils.

0.099 +1.004.000.032 *0.454.20(ⅴ)Test the trust relationship with teachers.

not significant: n.s. p<.10: + p<.05: * p<.01: ** p<.001: ***

KMIS 2024 - 16th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

226

Table 3: Results of t-tests for degree of similarity.

Table 4: Percentage of similar simulated situations.

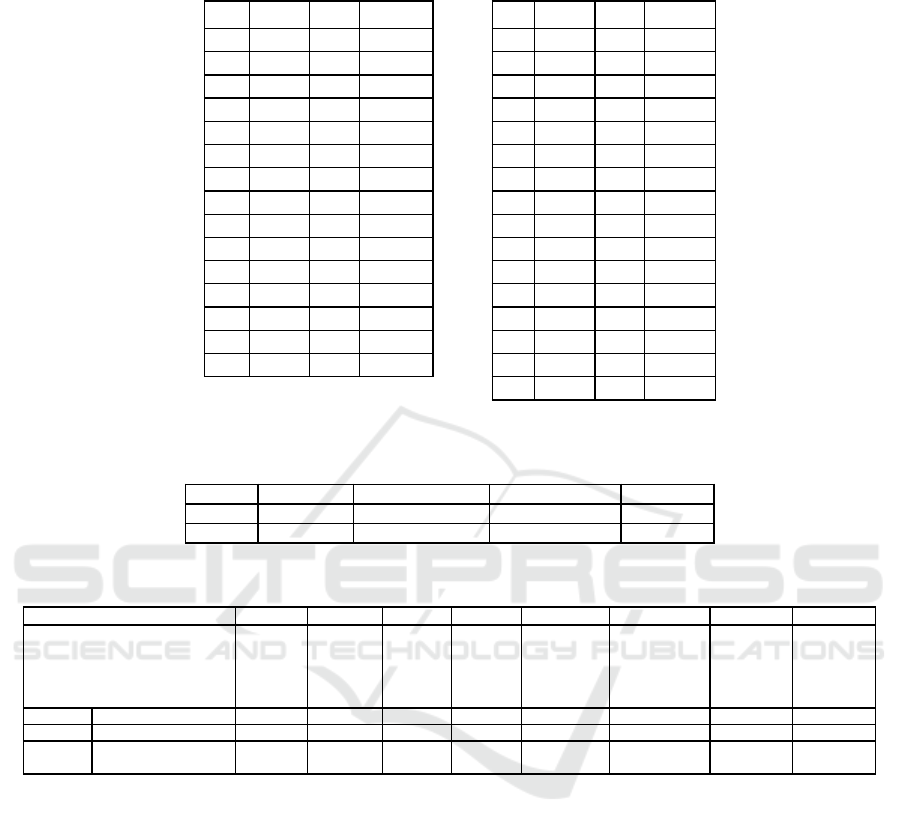

Table 5: Frequency of simulated situations that create the management skills confirmed in the experiment.

The results presented in Tables 3 highlight the

significant differences in the degree of similarity and

frequency of management behaviors that were

confirmed in the experiment. A one-sample t-test was

conducted to determine whether the mean similarity

scores for the simulated situations significantly

differed from the expected mean score of 3. To

determine the proportion of simulated situations that

occur in the microteaching designed by the authors

that are close to the actual situations experienced by

the group of evaluators, a one-sample t-test was

conducted using the results of five responses to a total

of 31 simulated situations, 15 from Design1 and 16

from the Design2.

Table 4 presents the percentage of similar

simulated situations by using scores of Tables 3.

From these analyses, key findings from the

statistical analysis indicate that the microteaching

sessions designed in this study approximate real

classroom scenarios in approximately 60% of cases,

providing useful insights for future study.

In addition, a chi-square test was used to compare

the frequency of different types of management

behaviors observed in the two designs, revealing

significant differences in specific behaviors from

Table 5. A chi-square test revealed no significant

difference between the two designs in terms of overall

learning opportunities for management behaviors.

However, a subsequent analysis using the data in

Table 5 found significant differences in the specific

types of management behavior opportunities

experienced by the teacher role (χ² (7) = 110.894, p <

.01).

Desi

g

n2Desi

g

n 1

P-valueS.D.MeanNo.P-valueS.D.MeanNo.

n.s.1.33.8

1

***0.454.8

1

***0.454.8

2

***0.454.8

2

**0.584.5

3

**0.554.6

3

n.s.0.713.0

4

***0.454.8

4

**0.454.2

5

n.s.1.34.2

5

*0.453.8

6

n.s.1.673.6

6

**0.554.4

7

n.s.1.793.6

7

n.s.1.34.2

8

**0.844.2

8

n.s.0.553.4

9

**0.454.2

9

**0.454.2

10

*0.844.2

10

n.s.1.224.0

11

**0.554.6

11

***0.454.8

12

***0.454.8

12

*0.844.2

13

n.s.1.953.6

13

n.s.14.0

14

n.s.1.523.6

14

**0.554.4

15

*0.894.6

15

n.s.1.33.8

16

not significant: n.s. p<.10: + p<.05: * p<.01: ** p<.001: ***

Percentage Similarity (X-Y)No similarity (Y)Event(X)

0.6710515Design1

0.6310616Design2

HGFEDCBA

Give

cautions

and

warnings

for pupil

Give

formative

feedback

to pupils

Change

how to

communicate

with pupils

Encourage

pupil to

learn

together

Change

how to

learn

Change

notable

pupil

Change

how to

teach

Add new

tasks for

pupil

3151011511222Measured valueDesign1

306131541716Measured valueDesign2

61

(23.63)

11

(23.63)

23

(23.63)

2

(23.63)

20

(23.63)

5

(23.63)

29

(23.63)

38

(23.63)

Measured value

Expected value

Total

Design and Evaluation of Microteaching: Emergent Learning for Acquiring Classroom Management Skill in Teacher Education

227

Multiple comparisons using Ryan's nominal

levels revealed significant differences among

management behaviors. Inserting teaching materials

was more effective than changing the nomination

order, nomination-response rules, or response

methods. Changing the children's activities was more

effective than changing the nomination order or rules

but less effective than attention and instruction.

Additionally, changing the order of nomination was

less effective than changing the sequence of

questions, communication, or attention and

instruction.

Additionally, changing the order of nomination

was less effective than changing the sequence of

questions, communication, or attention and

instruction. Changing the sequence of questions was

less effective than attention and instruction. Finally,

changing the nomination-response rule was less

effective than changing the form of communication

or attention and instruction. Furthermore, it was

observed that F: changing the form of communication

<H: the way of attention/direction (critical ratio = 4.0,

p = 0.0002). Finally, it was found that G: changing

the method of response < H: the way of

attention/direction (critical ratio = 5.8, p = 0.0002).

These results indicate that through the practice of

the microteaching designed in this study, the teacher

roles had the opportunity to learn the management

behavior of inserting teaching materials rather than

changing the order of nomination, nomination-

response rules and response methods to establish a

lesson. It was evident that the students had the

experience. Similarly, it can be said that the teacher

role experienced the opportunity to learn the

management behavior of changing the form of the

children's activity rather than changing the order of

nomination or changing the nomination-response rule.

4 DISCUSSIONS

4.1 Environmental Assessment

It was found that the microteaching designed by the

authors could be practiced to enable learning in a

situation close to the actual unexpected behavior.

Furthermore, the similarity between the simulated

situation and the actual situation was approximately

60%, which means that more than half of all

situations in the microteaching designed by the

authors were inevitable situations in which the

teacher role had to invoke and create management

behaviors.

In other words, a certain quality is guaranteed as a

method for learning management behaviors to control

unexpected behavior.

4.2 Causes of Low Similarity

The following reasons can be given as to why a total

of 11 simulated situations that did not show

statistically significant differences were not close to

the actual situations.

One possible reason for the low similarity

between simulated and actual situations is the over-

exaggeration of certain student roles based on the

image cards. For example, a student role labeled C3

may have been overly disruptive due to a lack of

nuanced understanding of the behavior expectations,

leading to a deviation from realistic classroom

dynamics. Future research could involve more

detailed role-playing instructions to mitigate such

discrepancies. This indicated that, to have the

opportunity to learn in a context close to the actual

classroom, the children acting out C3 needed to be

given prior instruction to avoid overacting. However,

no differences were found in the proportion of

simulated situations that occurred within each

microteaching. In other words, there was no

difference in the type and number of simulated

situations occurring between the different designs.

4.3 Evaluation of Learning

Effectiveness

The teacher roles in both Design1 and Design2

experienced various management behaviors,

including attention, instruction, material insertion,

question sequencing, communication, and activity

changes. They found that unexpected behavior

triggered management behaviors like cautioning,

scolding, and interrupting the class. While students

were confused, the teacher roles learned to identify

key student roles, adjust their lesson plans, and

implement appropriate management actions. This

suggests the method's effectiveness as an emergent

learning approach for invoking and creating

management behaviors.

4.4 Comparison with Previous Studies

This study proposed a method to cultivate classroom

management skills in pre-service teachers using

microteaching.

Previous studies have highlighted the potential

importance of emergent learning in classroom

management. Haug (2017) noted the varying

KMIS 2024 - 16th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

228

definitions and implementations of inclusive

education across countries, emphasizing the need for

flexible responses to students’ needs. This aligns with

our findings, suggesting that emergent learning,

where preservice teachers adapt to unexpected

behaviors, may be beneficial for effective classroom

management.

Additionally, this study supports the potential

effectiveness of microteaching in improving teaching

skills such as attention management, questioning, and

class control (Gower et al., 1995; Capel et al., 1998;

Kilic, 2010). Our findings indicate that microteaching

could help in teaching emergent behaviors to handle

unexpected classroom disruptions.

Furthermore, Sakuma et al. (2019) developed

image cards to assist student roles in microteaching,

enhancing its effectiveness. Our study builds on this

by incorporating unexpected behaviors into

microteaching sessions, suggesting that this approach

may provide a more realistic and comprehensive

training experience for preservice teachers.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study provides insights into the design and

implementation of microteaching sessions that

incorporate unexpected student behaviors. While the

findings suggest potential benefits, further research is

needed to establish more robust scientific validation.

The microteaching sessions provided valuable

insights into the challenges faced by teachers in

managing unexpected behaviors. However, more

comprehensive studies are needed to validate these

findings across different contexts and sample sizes.

By refining the pre-teaching preparation of student

roles and considering more diverse simulated

situations, future studies can better assess the

effectiveness of emergent learning strategies in

classroom management training.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant

Numbers JP24K00423. This work utilized OpenAI's

ChatGPT for initial drafting, which was thoroughly

reviewed, edited, and supplemented by the authors.

We therefore assume full responsibility for the final

content of this publication.

REFERENCES

Allen, D. W. (1967). Microteaching: A description.

Stanford Teacher Education Program.

Asada, T., & Sako, H. (1991). Identification of and a model

for classroom management behaviour in instructional

situations: Introducing a managerial point of view in

analysis of classroom instruction. Japan Journal of

Educational Technology, 9(1), 12-26. https://doi.org/

10.15077/jmet.15.3_105

Capel, S., Leask, M., & Turner, T. (1998). Learning to

teach in the secondary school. Routledge.

Gower, R., Phillips, D., & Walters, S. (1995). Teaching

practice handbook. Heinemann.

Fujioka, N. (1991). Methods of classroom research using

stop-motion technique. Japan Journal of Classroom

Research, 4(2), 102-115.

Haug, P. (2017). Understanding inclusive education: Ideals

and reality. Scandinavian Journal of Disability

Research, 19(3), 206-217. https://doi.org/10.1080/

15017419.2016.1224778

Kilic, A. (2010). Learner-centered microteaching in teacher

education. International Journal of Instruction, 3(1).

Pittman, S. I. (1985). A cognitive ethnography and

quantification of a first-grade teacher’s selection

routines for classroom management. The School

Journal, 85(4), 541-557.

Sakamoto, T. (1981). The effects of simplified

microteaching for pre-service teacher training.

Educational Technology Research, 5, 1-13.

Sakuma, D., Takaishi, T., Imai, T., Hasegawa, K., &

Murota, M. (2019). Designing microteaching using

imagination-cards of pupil’s actual condition. Japan

Journal of Educational Technology, 43(2), 91-103.

https://doi.org/10.15077/jjet.42163

Yoshizaki, S. (1988). Development of a model for teachers’

decision making. Japan Journal of Educational

Technology, 12(2), 51-59. https://doi.org/10.15077/

etr.KJ00003899067

Design and Evaluation of Microteaching: Emergent Learning for Acquiring Classroom Management Skill in Teacher Education

229