Decentralizing Democracy with Semantic Information Technology: The

D-CENT Retrospective

Harry Halpin

a

Center Leo Apostel, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium

Keywords:

Ontologies, Direct Democracy, Governance, Standards.

Abstract:

One of the central questions facing democracy is the lack of engagement from ordinary citi zens. D-CENT (De-

centralized Citizens ENgagement Technologies) used cross-platform and decentralized technologies, ranging

from Semantic Web ontologies to W3C federated social web standards, helps communities to autonomously

share data, collaborate and organize their operations as a decentralized network. With the benefit of hindsight,

we can analyze why this decentralized and standardized approach, whil e successful in the short-term, did not

succeed in sustaining engagement in the long-term and why blockchain systems may be the next step f orward.

1 INTRODUCTION

While Web-based technologies have been remark-

able in attracting engagem ent, even a ddictive en-

gagement in social media, there has been declining

engagement in democr atic political p rocesses. The

central research question is then: How can we use

Web-technologies to enable increased engagement in

democratic processes? One hypothesis is the Web

help rebuild democra tic en gagemen t by relying on the

same principles that drive engagement on commercial

platforms, such as notification s.

Traditional democratic institutions were built in

a pre-Web era, and so relied on representatives due

to the latency req uired for face-to-face d ecision-

making and de liberation. A kind of radical democ-

racy, direct democracy, differs from traditional rep-

resentative democracy insofar as the entir e comm u-

nity is considered to engage in democratic deliber-

ation and decision-making, rather than a few rep-

resentatives (Kling et al., 2015). With increasingly

ubiquitous connectivity, co uld the entire paradigm be

changed to one of digital direct democracy where

people deliberate and even make collective d ecisions

over the internet? Across Europe, attempts to en-

gage citizens and so cial movements in democratic

decision-making for the social good using digital plat-

forms have not yet scaled or reached wide usage.

Thus, a secondary hypothesis is that Web technolo-

gies can enable new forms of wider radical demo-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2143-6965

cratic engagement beyon d traditional representative

politics.

There has been many platforms built for increased

democra tic engageme nt, but many of them have not

been successful. Most of these platforms lack fea-

tures and have complex user-interfaces, which might

leave many people unable to meaningfully partici-

pate in their democr atic pro cess via the Internet. A

few existing platform s, such a s LiquidFeedback used

by th e Pirate Party, have been specifically designed

to engage users into large-scale Interne t-based d emo-

cratic process that goes beyond the limits of tradi-

tional social media (Kling et al., 2015). In general,

collective deliberation is shown to increase the collec-

tive intelligence of groups beyond its individual mem-

bers (Woolley et al., 2010). There is some evidence

that this pro c ess can reliably be done via online delib-

eration (Klein, 2007 ). Still, most of th ese initiatives

did not succeed in scaling the p rocess of large-scale

collective action and participation outside relatively

small commun ities. It is unclear if this is a limit of

direct democratic structures or if digital tools could

scale social innovation across society w ith the right

set of digital tools (Halpin and Bria, 2015).

One central insight fro m the Web is that open stan-

dards and interoperability led to the initial take-up o f

the Web, even though currently the Web is becom-

ing a series of closed platforms. On the other hand,

most e-government services for democratic engage-

ment are closed platforms. Thus, our final hypoth-

esis is that lack of engagement is due to the inability

of these platforms to meaningfully intero perate across

342

Halpin, H.

Decentralizing Democracy with Semantic Information Technology: The D-CENT Retrospective.

DOI: 10.5220/0013019800003825

In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST 2024), pages 342-349

ISBN: 978-989-758-718-4; ISSN: 2184-3252

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

community boundaries, and Semantic Web ontologies

combined with W3C Social Web standards could ad-

dress these scaling issues across loc al and national

boundaries.

Developing a common fo rmal vocabulary - an ‘on-

tology’ - is one solution to the issue of interoperabil-

ity in e-government (Obrst, 2003 ), and this study at-

tempts to build software to decentralize e-governm ent

using open standards. The software, c alled D-CENT

(Decentralized Citizen EmpowermeNT)

1

condu c te d

multi-year pilots across Europe from 2015-2019

2

to

accelerate the development o f distributed alternatives

for on line de liberation and data governance. The

goal was to develop a framework for the deploy-

ment of decen tralized networks for community-driven

democra cy wh ich are b oth easy to use and properly

aligned with fun damental righ ts. Some of the fea-

tures were specifically designed to link into existing

formal structures of de mocratic power; others pur-

ported to build the capacity for the deployment of

new democratic institutions that could h arness the

network effects of digital tools and real-time collabo-

ration to solve social problems. To our knowledge,

our effort was the first time ontologies have been

used to strengthen democratic politics in a bottom-

up manner while engaging institutions, in contrast

to the top-down traditional uses of ontologies in e-

Governance (Mampilli and Meenakumari, 2012) and

newer efforts in blockcha in-based Decentra lized Au-

tonomous Organizatio n (DAOs) that seek to replace

institutions but lack common stand a rds (Sims, 2019).

This paper provides a retrospective on the ambi-

tions, successes, and ultimate failure of decentraliz-

ing democracy using open standard s. The D-CENT

project ran from 2014-201 6, and parts of the system

in op eration till 2018 across Finland and Iceland in

2019. The primary c a se-studies are in Spain, Ice-

land, and Finland, and we u sed a lean user experi-

ence methodology to un derstand the distinct problems

each of these co mmunities experienced and how tech-

nology could help address these issues as described

in Section 2. Although there is not enoug h space to

discuss the fascinating results of these user-interview,

the technical architecture is overviewed in Section 3,

with a focus on the delibera tion platform Objective8

and the notifications tool Mooncake, as well as how

we use the federated W3C Soc ia l Web stack to com-

municate between the various tools. Lastly in Sec-

tion 4, we give reasons for the succe ss and failures of

D-CENT itself to scale .

1

https://dcentproject.eu/

2

The software was completed at the end of the project

in 2016, but the actual attempted usage of the software con-

tinued after the project until 2019.

2 LEAN USER EXPERIENCE

These case-studies were done using the qua litative

interview-based ‘lean user experience’ methodology

in order to develop usable ontology-based software.

The main tenet of the lean user experience method-

ology is technology should prioritize human needs,

and the first step in building technology is to un-

derstand the concrete human needs via detailed case

studies (Ries, 2011). A series of wh at are called ‘ le a n

inception’ events were done in Finland, Iceland and

Spain to gather information about their pr oblems, and

how currently existing software did or did not address

these issues. The goal is to create the minimal, i.e.

‘lean,’ amount of software to address the problem that

people actually have, rather than the problem that the

software developers and ontology engineers thought

their users have.

The rea son why these ca se-studies were chosen to

inform - and later, pilot - the D-CENT design was

because they were all organically usin g technology

to build direct democracy, although without intero p-

erable components. Also, each of these case stud-

ies is on a different scale: Finland on the scale of

an entire nation-state via a ‘top down’ model based

on sharing open data and influencing the Parliament,

while in Iceland the focus was on th e making city

government mor e democ ratic. The last case-study,

Barcelona, was focused on direct democracy at the

neighborhoo d level.

2.1 Finland

One of the more successful efforts in crowd-sour cing

policy proposals on the nation-level is Open Ministry

in Finland.

3

Since a constitutional amendment made

it possible in 2012, Open Ministry crowd-sources pro-

posals from citizen campaigns and puts them in front

of Finnish Parliament. On November 28th 2014 the

first initiative launch e d by the Open Ministry was ac-

cepted by the Parliament when the Finnish Parliament

voted 105 ‘in favor’ and 92 ‘against’ for the equal

marriage law proposal giving gays and lesbians eq ual

marriage rights.

At the same time, Finland has become one of

the world-leadin g nations in terms of th e produ ction

of open data. Under the leadership of mayor Jussi

Pajunen, th e City of Helsinki has adopted a m ore

open and citizen-centric approach to data, where it

opened its interna l document management system,

called ‘Ahjo,’ and released all the agendas a nd deci-

sion items of the city cou ncil and the city’s subcom-

mittees as Open Data available through a JSON API

3

https://openministry.info/

Decentralizing Democracy with Semantic Information Technology: The D-CENT Retrospective

343

called ‘OpenAhjo’ so that developers could build ap-

plications on it.

4

After this, the rest of Finland has

been following suit, with in 2020 OpenAhjo still be-

ing used as a part of larger open government APIs

around Linked Events and Geoserver mapping.

2.2 Iceland

Better Reykjavik

5

was launched in 20 10, a week be -

fore the municipal elections in Reykjavik using the

Your Priorities codebase,

6

and became a major suc-

cess in direct demo c racy. All parties received the

capability to crowd-source ideas for their campaigns

like the Pirate Party. The ‘Best Party’ used the sys-

tem extensively, and won 6 of the 15 seats of Reyk-

javik City Council in the 2010 election. Thus, when

J´on Gnarr became mayor of the capital of Iceland, he

called on Reykjavik citizens to use the Better Reyk-

javik online platform also during the coalition talks

that happened after the election. During the elec tions,

40% of Reykjavik’s voters u sed the platform and

almost 2,000 political policies were crowd-sourced.

Since 2010 12,00 0 registered users have submitted

over 5,000 ideas an d 8,000 priorities, with 257 prior-

ities have been formally reviewed with 165 accepted

since 20 10. The 10-15 top priorities are being pro-

cessed by Reykjavik City Council and voted upon at

meetings every month. Therefo re, it functions very

similarly to Open Ministry but on a city-wide rather

than local level. The Icelandic government started in

2018 to use the Your Priorities platform on an Iceland-

wide basis as Better Iceland.

7

As of 2020, the Your

Priorities platform hosts 114 different communities

outside Iceland, ranging from NHSCitizen in the UK

to Forza Nazzjo nali in Malta.

2.3 Spain

In Spain, D-CENT primarily worked with Guanyem

in Barcelona, a coalition of neighborhood assem-

blies demanding a more democratic use of data. The

rise of ‘15M’ m ovement as part of the ‘movement

of the sq uares’ in 2011, produced an unprecedented

politicization of pe ople in Spain, cutting across the

whole society, including even the traditiona lly con-

servative and apolitical secto rs. This n ew politics

are characterized by a prioritization of direct democ-

racy that led to the eme rgence of new c itizens’ coali-

tions such as Guanyem (“Let’s Win” in Catalan).

4

https://dev.hel.fi/apis/openahjo/

5

https://betrireykjavik.is/

6

https://www.yrpri.org/

7

https://betraisland.is/

Guanyem h as also been very interested in technol-

ogy, with ma ny of its pa rticipants wanting some form

of ‘ope n sou rce’ municipalism to increase participa-

tion and transpa rency of more centra lize d governmen-

tal decision-making. At the time of the experiments,

the Guanyem coalition was made up o f 13 thematic

axes, 6 working committees and around 15 -20 neigh-

borhood assemblies, with more than 1000 volunteers

that are participating o n a daily basis. It began an af-

filiation with the new Spain-wide Podemos party.

Reddit was the actual core of the participation in

Podemos, through the space called ‘Plaza Po demos’

(Podemos Square).

8

The daily average attendance

is 15, 000 unique visitors, with more than 270,000

unique visitors and more than 2,625,000 page view

during October 2014.

9

This is of interest, as Podemos

had at the time 220,000 registered people. However,

Reddit did not allow sophisticated po lling and voting

on actu a l decisions. This led to a centralization of

decision-making by the party hierarchy by Podemos.

In contr ast, local groups affiliated (but distinct

from) with Podemos such as Guanyem had experi-

mented with software such as Agora Voting,

10

but this

software was proprietary and so could not be modi-

fied. Further more, each of the neighborho od coun-

cils would like to have their own polls and votes, but

would like to be able to optionally send the results

of th ose polling and voting activities to other politi-

cal groups: So a single neighborhood like Las Ram-

blas could have their poll on a policy proposal sent to

the Barcelona-wide Guanyem in ord er to determine if

the policy proposal was a cceptable. However, what

was needed was a new kind of intero perable tool that

could interoperate and fed e rate between the various

neighborhoo d assemblies in Barcelona, and eventu-

ally across all of Spain and even Europe. Ther e fore,

based on this vision, the D-CENT software was built

as a tool for ‘dual power’ by a federation of demo-

cratic assemblies.

3 ARCHITECTURE

The overarching vision of the D-CENT architecture

is that each group will maintain its own data, delib-

erations, and polling using its own autonomous on-

line presence, a D-CENT node, but that the differ-

ent nodes will be able to communicate and take ac-

tions in a decentralized manner over a network of

8

http://plaza.podemos.info

9

Note usage has been in steady decline since the insti-

tutionalization of t he party after 2015 and its decline in the

polls since 2019.

10

https://www.agora.vote/

WEBIST 2024 - 20th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

344

Figure 1: D-CENT case studies and users.

D-CENT nodes. Using D-CENT, assemblies could

distribute polls across different jurisdictions and dis-

cuss common actions over global issues such as cli-

mate change. The node s should start with the ex-

isting D -CENT-affiliated projects in Finland, Ic eland,

and Spain, but allow exten sio n to new neighborhoo ds,

cities, and even countries. Therefore, this project

could be considered similar to architecture to Tim

Berners-Lee’s Solid project, but based on a collective

community da ta store rather than an individual store

of personal data for each person .

11

The problem was that each of these communities

had not only linguistic differences, but vast differ-

ences in scale and process in how they went about

deliberating on policy proposals, and the D-CENT ar-

chitecture had to be general purpose enough to handle

all of these case-studie s. Therefore, a Semantic Web

deployment approach was chosen for the architec-

ture. No te blockcha in technologie s do not have open

standards to communicate structured data by default

and were very immature when the D-CENT architec-

ture was be ing created. The approach chosen by D-

CENT was to fo cus on an extensible ontology-based

approa c h to stru cture the data in the communication

between nodes. ActivityStreams 2.0, a W3C Seman-

tic Web stan dard by the W3C Social Web Working

Group,

12

was chosen as the basis of the ontologies to

be used by eac h community. As this stan dard a lso

allowed serialization into JSON, it could be easily

added to existing platform s by virtue of customiz-

ing the ActivityStreams ontology without changing

the existing platform. The use of ActivityStreams

would then let existing directly democratic platforms

send out notifications of events to other platforms, i.e.

other D-CENT nodes.

A number of othe r compone nts had to be built

for real-world deployment. First, users themselves

needed to be able to be identified for purposes of po-

11

https://solidproject.org

12

http://www.w3.org/TR/activitystreams-core/

litical delibera tion, in order to prevent spam and other

sybil attacks. Although the exact method for connect-

ing an ‘online’ identity to physical ide ntity was le ft

to the political community using D-CENT (ranging

from checking passports in-person to allowing anony-

mous usage), an identity sy stem of some type was

needed. Also, users would need a way to authenticate

securely to the system in order to subscribe to and

receive notifications to these feeds. Therefore, cryp-

tography needed to be deployed. Each node should

control locally for its users or let their users control

their own private key such that the cryptographic key

material needed to validate every user would be reg-

istered with a node via the user’s public key.

Each decen tralized compon ent was specified us-

ing open standards would allow pre-existing direct

democra cy tools like OpenAhjo and Better Reykjavik

to become compliant with the D-CENT architectur e

rather than for ce these pre-existing systems to use

new systems using Semantic Web techn ology. In-

stead, pre-existing systems would simply need to add

support for a finite number of open standards and

Semantic Web ontologies (using th e D-CENT ontol-

ogy extensions to ActivityStreams) via open-sourc e

libraries. This would allow existing direct democratic

software to easily commun ic a te , for new applications

to be built on top of open standards that could be used

with any D-CENT node, and for data portability for

users between D-CENT nodes. So, each D-CENT

node should have the following minimal components,

with each of the components commu nicates via Ac-

tivityStreams with the D-CENT ontology, as explored

in each of the following subsections:

1. Identity: The personal data store of each user that

is part of a D-CENT nod e, with a sample applica-

tion (Stonecutter). It is b ased on the OAuth 2.0

standard and an extensible version on the W3C

VCard ontology.

2. Notifications: The notification en gine that lets

D-CENT nodes notify users of new events (dis-

cussions, policy proposals, polls, votes, etc.) via

the W3C ActivityStreams ontology. The sample

application Mooncake provides the se functions to

users who subscribe to ActivityStreams from D-

CENT nodes, and developers via the Coracle ap-

plication.

3. Deliberation: The deliberation platfo rm that lets

users pro pose new policy proposals and discuss

them, using Objective8, and so sends out notifica-

tions to users.

Existing applications would need to implement these

functions via open standards on top of their exist-

ing code-base using open standards, and for new D-

Decentralizing Democracy with Semantic Information Technology: The D-CENT Retrospective

345

Figure 2: D-CENT architecture.

CENT nodes, example software that has been compli-

ant with the standards has been written. As shown in

Figure 2, a particular API (Helsinki Decisions API) is

made compatible with the Semantic Web-based Ac-

tivityStreams via extending the standard ActivityS-

treams classes. This use of ActivityStreams allows

the Decision API to dynamically display on a map,

where a third-party party developer can make their

own custom vocabulary. User s can then access and

receive notifications via Mooncake afte r authenticat-

ing via Stonecutter - and other third party systems,

including other D-CENT nodes, can access the Activ-

ityStreams.

3.1 Identity: Stonecutter

Stonecutter is a privacy-enhanced single sign-on

(SSO) tool that also provides identity man agement

for D-CENT nodes, allowing a user to easily authen-

ticate and access their notification s an d other appli-

cations across D-CENT nod e s without having to use

centralized third-party platforms like Facebook and

Google tha t may invade their privacy. This SSO ser-

vice can be easily integra ted with other tools hosted

by D- CENT nodes via the use of the OpenID Con-

nect, a profile of the IETF standard OAuth 2.0.

13

The

use of OAuth 2.0 across D-CENT nodes allows or-

ganization s to share their users, with user permis-

sion, with other organization s and allows users to

have a single consistent identity across multiple D-

CENT n odes. This is u seful as a user m ay have a

single identity across loca l (neighborhood), munici-

pal ( city), national, and even transnational (Europe a n

Union) dire ctly democratic applications, and a user

may also want to move between lo cations (such as

from Barcelona to Rome) without having to create a

13

https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc6749

new identity. Stonecutter stores user data as VCard,

14

but is extensible in a customizable manner via the us-

age of the Semantic Web W3C VCard ontology.

15

The exportation of VCards and the self-hosting of

data securely a llows D-CENT nodes to be compliant

with the General Data Protection Directive. Further-

more, Stonecutter uses Docker so it is easy for orga-

nizations that wish to host D-CENT nodes can easily

install the software on local servers, so that valuable

and private user data is not hosted in foreign juris-

diction that may not comply with the General Data

Protection Directive.

3.2 Notifications: Mooncake

Notifications are the hear t of D-CENT. Mooncake

is a notifications tool that securely notifies mem-

bers of a D-CENT node of activity in the wider D-

CENT ecosystem, including on other D-CENT nodes.

Mooncake is fundamentally an ActivityStream en-

gine built in Cloju re (a functional langu age compat-

ible with Java and so having acce ss to commonly-

needed Java libraries) that supports OAuth 2.0 for

sharing data a bout ActivityStreams.

16

As Mooncake

focuses on users, a complementary program called

Coracle was developed that serves as a notifications

server which stores activities in orde r to the activity

stream at an endpoint for third-par ty applications to

access.

17

Mooncake (and other D-CENT enabled ap-

plications like Objective8) request these tokens, and

use the m to perm it access to restricted actio ns within

the applications themselves. Through Coracle, appli-

cations (like Better Reykjavik, Objective8, Democra-

cyOS, etc.) can produce Ac tivityStreams 2.0 JSON

docume nts which c an be consumed by any other ap-

plication that queries the relevant endpoint. Moon-

cake. Mooncake queries the endpoint of any Activi-

tyStream producer and consumes the r esult, combin-

ing the results into a single feed that can then be dis-

played to the user as shown in Figure 3. A user can

freely use ( a nd a developer can free ly implement) an-

other a pplication that consumes ActivityStreams data

and use it in conjunction with Moonca ke or instead

of it. The application simply has to be aware of any

extensions to the ActivityStreams vocabulary made

by the application, which should be straight-forward

as lon g as the ontology is published and discover-

able due to using Linked Data gu idelines (Bizer et al.,

2011). This fulfills the D-CENT goal of simple de-

14

https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc6350

15

https://www.w3.org/2006/vcard/ns-2006.html

16

The open source code is available at https://github.c

om/d-cent/mooncake

17

https://github.com/d-cent/coracle

WEBIST 2024 - 20th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

346

Figure 3: Mooncake Notifications Display.

Figure 4: Example usage of D-CENT ontology for deliber-

ation.

centralized integration between both new and old ap-

plications with in the sam e eco system should be mad e

possible.

Notifications can be added to an existing D-CENT

node so that users ca n stay up to date with multiple

other D-CENT node through a single interface. These

activities could include actions newly created policy

proposals, in the case of Objective8, database activ-

ity in open databases, an d so on. All notifications use

the the open standard Activity Streams 2.0 (AS2) with

class extensio ns to the ActivityStream ontolo gy to

support direct democracy via the D-CENT o ntology.

Currently, Objective8, OpenAhjo (City of Helsinki’s

Decision API) and Better Reykjavik (Your Priorities),

publishes ActivityStreams using the D-CENT ontol-

ogy that can be consumed by Mooncake. ActivityS-

treams features a simple ontological model based on

a RDF triple (as defined by the W3C Semantic Web

standard semantics f or RDF

18

), where an actor that

takes an action on a object. The action may also have

a seco ndary effect on a target. All of these are defined

as RDF classes. For example, in the Decision API, the

actor is a group that makes a decision, such as Finnish

Parliament. The action could be to add the decision

to those ratified on an issue given by an issue-url. Ev-

ery n otification is given a timestamp via the predicate

published. This is illustra te d in Figure 4.

18

https://www.w3.org/TR/rdf11-mt/

3.3 Deliberation: Objective8

Objective8 is a policy drafting tool that allows organi-

zations to work with their members to produce crowd-

sourced policy p roposals. Objective8 was also pro-

grammed in Closure with a Docker instance for easy

installation.

19

Traditionally policy documents have

been written by a single person or small team, and

only distributed on ce com plete. Objective8 has been

designed to help directly democratic organizations

create policy in a more open, tran sparent and collabo-

rative way. It allows a wider community to shape and

inform the policy drafts via proposin g an d deliberat-

ing on policy proposals. The tool a llows members of

a community to r eview, comment and annotate draf ts

of a policy. The feedback provided by the community

is then made accessible to the policy writers so that

it can be assessed and included in the next version of

the draft. Members of the D-CENT node are also able

to become policy writers them selves if they choose

to. Through the too l, users can gather community

opinion, generate ide as, share, discuss, and collabo-

rate with experts to draft the new policy. This could

include spe cific policie s, manifesto pa ges, and so on.

The policy writers are able to view an aggregation of

their feedback for all their objectives on a dashboard

using ActivityStreams 2.0 , similar to Mooncake for

users.

Objective8 is used to integrate and aggregate data

in different contexts to cr eate a multi-channel multi-

organization participation experience where parties

contribute to the cyclic creation, use, reuse, and en-

riching of the policy p roposal. Objective8 in cludes a

Mongo D B datastore in order to store JSON (includ-

ing RDF data formatted as JSON) as well as links

to a native RDF triple-store for integration of RDF

data. These data bases allow new kinds of open data

to be added to policy proposals beyond simple written

comments and annotations via crowd-sourcing. For

example, the integration of geosp atial data allows Ob-

jective8 to have map visualization to print items in the

ActivityStream on a map to enable local real-life in-

teraction in betwe en users. Th e exten sib le RDF D-

CENT ontolog y is the backbone of Objective8.

20

It

extends the ActivityStreams 2.0 RDF vocabulary as

given below:

21

19

The open source code is available at https://github.c

om/d-cent/objective8

20

The D-CE N T ontology as RDF Schema is available at

https://github.com/d-cent/activitystreams-spec

21

The table uses

as

as the prefix for the ActivityStreams

2.0 and

dcent

for the D-CENT ontology.

Decentralizing Democracy with Semantic Information Technology: The D-CENT Retrospective

347

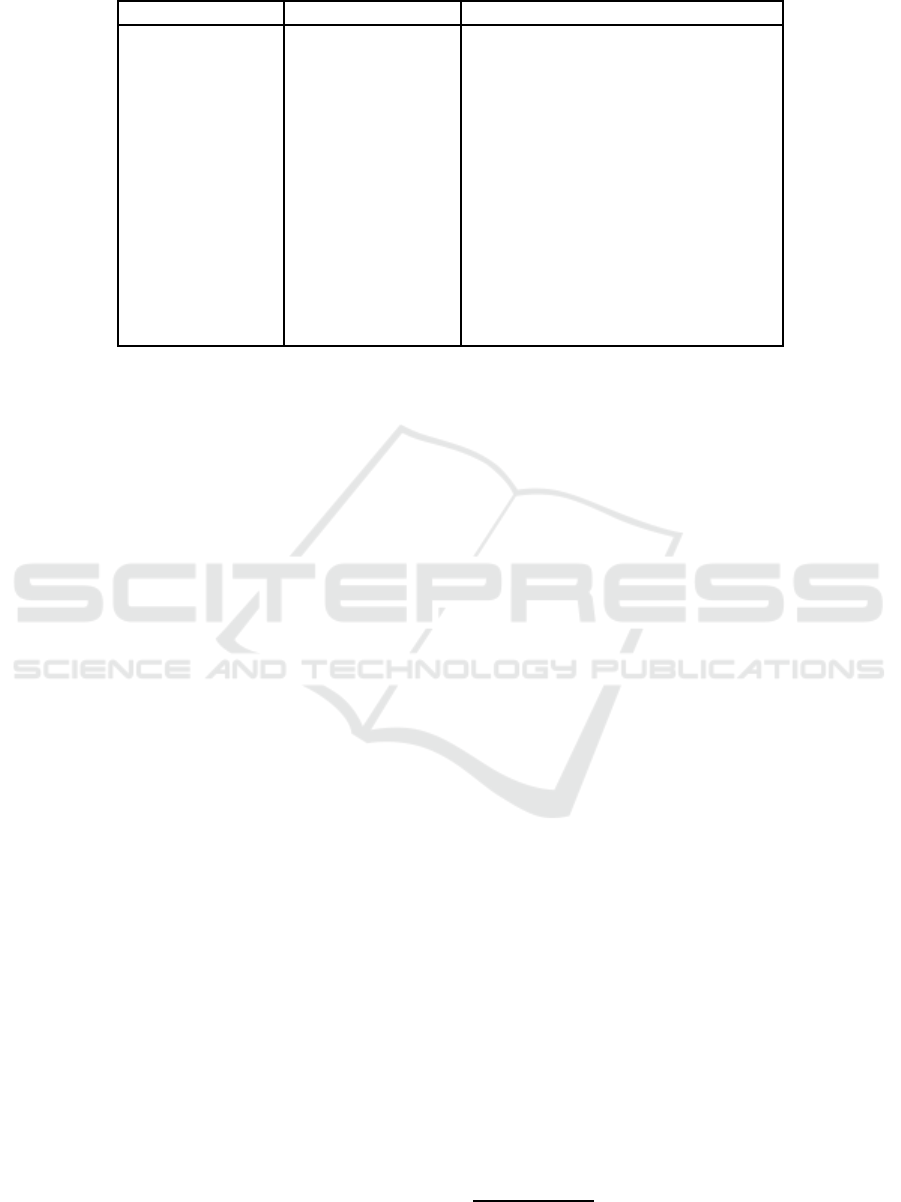

Table 1: D-CENT Ontology.

Class name

rdfs:SubclassOf

Description

Group

as:Actor

The group making the decision.

Issue

as: Content

An issue that needs a policy decision.

Proposal

dcent:Issue

A prop osal to address an issue.

Decision

dcent:Proposal

A prop osal that has been accepted.

create

as:Activity

Creation of a new issue.

add

as:Activity

Addition of a new proposal.

accept

as:Activity

Suppor t for a proposal.

reject

as:Activity

Rejection of a proposal.

abstain

as:Activity

Abstention from a proposal.

Comment

as:Content

Textual co mment of comment.

Annotation

dcent:Comment

Annotation of content.

Argument

dcent:Argument

Argumentation point over proposal.

ArgumentAgainst

dcent:Argument

Argument again st a prop osal.

ArgumentFor

dcent:Argument

Argument for a proposal.

4 CONCLUSIONS

D-CENT was an ambitious attempt to build a n decen -

tralized infrastructure for direct democ racy that would

be interoperable across multip le social movements

and scales of democr atic governance. In its ea rly

stages from 2014 to 201 6, D-CENT shows promise

as a tool for autonomous and decentralized decision-

making and voting in assemblies. The hope was that

after testing, multiple assemblies and municipalities

each with their own D-CENT nodes, would federate

across Eur ope, leading to large-scale dec e ntralized di-

rect democracy via assemblies. However, ultimately

the system launched with m uch fanfare in from 2014-

2016 but by the time of COVID in 2020, D-CENT

ultimately did not take root. Although federation re-

mains a powerful potential capacity of still popular

platforms like Better Reykjavik via their use of the D-

CENT ontology and ActivityStream s, the actual fed-

eration capabilities were rarely used in practice.

The reasons for this lack of increased democratic

engagement are multiple. First, developers found it

difficult to understand and use, much less extend the

Semantic Web ontologies used by ActivityStreams,

preferring traditional APIs to RDF-based ontologies.

Therefore, D-CENT was not widely integrated into

existing platforms with real users. Second, although

we aimed to allow users to use D-CENT without in-

teracting with tr aditional tools like Facebook, Google,

Twitter, and Reddit, this may have backfired: Users

simply did not want to set-up their own account on

Stonecutter even if D-CENT allowed custo mized ca-

pabilities fo r communication within an assembly or

other political group, instead preferring to stay with a

small number of centralized commer c ia l providers. It

was simply too much hassle to use a personal data-

store and receive a separate stream of notifications

other than those already sent by Instagram.

Lastly, there also may need to be a change of ar-

chitecture: At the present mom ent, ther e is interest in

blockch ain-based systems that feature more a dvanced

cryptography a nd a more decentralized peer-to-peer

architecture tha n offered by the D-CENT f ederated

architecture . While there was interest in blockchain

technologies inside of D-CENT, in pa rticular commu-

nity currencies, these were never integrated into the

actual software. The same issues of scalability, lack

of developer familiarity, and users inability to migrate

to new systems a lso are challenges for bloc kchain

software. These were tackled within the DECODE

project,

22

which continued the work of D-CENT us-

ing blockchain technology. The advanced crypto gra-

phy of blockchain technology could offer a number

of features that could critically improve over th e D-

CENT approach. For example, u ser key-material was

unwieldy in Stonecutter, and a blockchain-based wal-

let approach would have likely been more successful

in terms of incentivizing particip a tion than just noti-

fications. From a security and trust perspective, it is

also better to have a blockch ain that keeps a reco rd of

the polls, deliberatio ns, and decisions rather than a set

of local if corruptible databa ses as used in D-CENT.

While users were notified of new events for demo-

cratic participation, they lacked any incentives to par-

ticipate, like tokenized reputation points or awards.

Lastly, the system is not anonymous, so users are

linked to their votes via their public key. For exam-

ple, mix-networking sy stems could unlink a vote from

a user via mixing, and so let systems like D-CENT

eventually engage in private and secure verifiable vot-

22

https://decodeproject.eu

WEBIST 2024 - 20th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

348

ing (Jakobsson et al., 2002) .

The underlying need for a radically more d emo-

cratic and cross-border politics are more clear in 2024

than in 2014, and – as it is clear such functional-

ity is not in the business interests of p rivate compa -

nies such as Facebook – software should rise to the

occasion. However, democratic e ngageme nt requires

meeting users where they a re, which is on a few large

platforms, not on the Semantic Web or blockchains.

Furthermore, the techno-centric approach put forward

by D-CENT did not succeed insofar as despite their

shared interest in digital direct democracy, the coun-

tries of Iceland, Spain, and Finland had vastly differ-

ent languag es and problems. What is needed more

than technology is a common political project and

political ideology that works across borders and lan-

guage barrier s. Software for democratic assemblies is

only useful if such assemb lies already exist and are

growing in popularity, an d there has n ot been a resur-

gence of democratic assemblies in Europe since 2011.

Yet as a perennial form of politics in revolutionary

moments from the early Soviets in Russia to the co-

operatives of the Spanish Civil War to the assemblies

in Arab Spring and Occupy, directly democratic as-

semblies will hopefully return due to the social unrest

brought about by climate change.

What D-CENT did was create the interoperab le

software that prefigured such a movement before it

even existed. Thus, it should be surprise the software

was not widely used, even if the pr oblems that it trie d

to solve were real. One should remember one cannot

create software ‘in media res’ of a revolutionary situ-

ation. Technology can only co me to the aid of radical

democra cy, but technical notions suc h as decentral-

ization and interoperability cannot by themselves call

democra cy into being.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The D-CENT project was co-o rdinated by Francesca

Bria, and numerous people took part in the project.

In particular, Pablo Aragon, Primavera Di Fillippi,

Jaako Korhonen, David Laniado, Smari McCarthy,

Javier Toret Medina, Sander van der Waal, Pia

Mancini, Robert Bjarnason, Mig uel Arana Caatania,

Evan Henshaw-Plath, Linda Roy, John Cowie, Felic-

ity Moon, Amy Welch, and Natalie Eskinazi. This

work is theirs and based on their deliverables for D-

CENT,

23

but any errors and opinions intr oduced are

mine alone.

23

https://dcentproject.eu/resource

category/publi cations/

REFERENCES

Bizer, C., Heath, T., and Berners-Lee, T. (2011). Linked

data: The story so far. In Semantic services, inter-

operability and web applications: emerging concepts,

pages 205–227. IGI Global.

Halpin, H. and Bria, F. (2015). Crowdmapping digital social

innovation with linked data. In European Semantic

Web Conference, pages 606–620. Springer.

Jakobsson, M., Juels, A., and Rivest, R. L. (2002). Mak-

ing mix nets robust for electronic voting by r andom-

ized partial checking. In USENIX security symposium,

pages 339–353. San Francisco, USA.

Klein, M. (2007). Achieving collective intelligence via

large-scale on-line argumentation. In Second Interna-

tional Conference on Internet and Web Applications

and Services (ICIW’07), pages 58–58. IEEE .

Kling, C. C., Kunegis, J., Hartmann, H., S trohmaier, M.,

and Staab, S. (2015). Voting behaviour and power

in online democracy: A study of LiquidFeedback in

Germany’s Pirate Party. In Ninth International AAAI

Conference on Web and Social Media.

Mampilli, B. and Meenakumari, J. (2012). A study on en-

hancing e-governance applications through semantic

web technologies. International Journal of Web Tech-

nology, 1(02).

Obrst, L. (2003). Ontologies for semantically interopera-

ble systems. In Proceedings of the international con-

ference on Information and Knowledge Management.

ACM.

Ries, E. (2011). The lean startup: How today’s en-

trepreneurs use continuous innovation to create rad-

ically successful businesses. Crown Currency.

Sims, A. (2019). Blockchain and decentralised autonomous

organisations (DAOs): The evolution of companies?

New Zealand Universities Law Review, 28(3):423–

458.

Woolley, A. W., Chabris, C. F., Pentland, A., Hashmi, N.,

and Malone, T. W. (2010). Evidence for a collec-

tive intelligence factor in the performance of human

groups. Science, 330(6004):686–688.

Decentralizing Democracy with Semantic Information Technology: The D-CENT Retrospective

349