Does Competition Affect Shareholder Activism and Institutional

Investors Used as Moderators?

Dr. Rahul Sharma

1a

, Dr. Rahul Singh Gautam

2b

, Bhakti Agarwal

2c

, Dr. Soma Sharma

2d

,

Sangeeta Paliwal

3

and Dr. Shailesh Rastogi

2e

1

School of Management, University of Engineering and Management, Jaipur, India

2

Symbiosis Institute of Business Management, Nagpur, Symbiosis International (Deemed University) Pune, India

3

University Librarian, Central Library, Symbiosis International (Deemed University) Pune, India

Keywords: Shareholder Activism, Competition, Python, Econometric, Regression.

Abstract: The primary objective of this paper is to evaluate the influence of compensation (comp.) on Shareholder

Activism (SHA), with institutional investors (II) serving as a moderating factor. This study uses a sample of

78 non-financial firms and employs regression by using Python to understand the outcome. Two distinct

models were employed in the analysis: a base model and an interaction model. The base model revealed a

negative correlation between compensation and SHA, suggesting that higher compensation levels coincide

with increased shareholder activism. In the second model, the impact of the moderator, II, was examined,

revealing no statistically significant effect on the relationship between SHA and compensation. From a

practical perspective, this study contributes uniquely to the literature by addressing a gap in research

concerning the relationship between SHA and compensation. Consequently, the findings hold potential

implications for policymakers, offering insights into how compensation levels may influence shareholder

activism.

1 INTRODUCTION

Investor confrontations with managers, regarding

dissatisfaction about some of the actions of the

corporates (David et al., 2007) and interventions in

the form of suggestions or feedback to modify the

corporate strategy for the improvement in the

performance of the company are a few of the signals,

indicating the increased shareholder activism (SHA).

According to sources Judge et al. (2010) and Rose

and Sharfman, (2014) the utilization of ownership

position to influence company policy and practices is

characterized as shareholder activism. As delineated

in references Wahal (1996) and Karpoff et al. (1996),

shareholder activism has transitioned the corporate

governance (CG) paradigm from a market-based

model to a political-based model. This transition can

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3990-2952

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4035-9638

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1956-4538

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9919-165X

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6766-8708

be attributed to a shift in mindset, wherein activism is

no longer perceived as a disruption of annual

meetings and a squandering of corporate resources

but rather as a legitimate avenue for stakeholder

engagement and influence (Goranova and Ryan,

2014)

SHA has changed the center of power in the

corporates and symbolized the fact that corporate

managers are accountable to the shareholders

(Thomas & Cotter, 2007); (Bebchuk, 2005) and

stakeholders of the firm (Reid & Toffel, 2009;

Rehbein et al., 2004). Although individual activists

have been successful in removing the board of

underperforming corporations (Rosenberg, 1999) the

change in the relationship between companies and

investors was not that significant. Even after many

significant changes and developments in the field of

68

Sharma, R., Gautam, R. S., Agarwal, B., Sharma, S., Paliwal, S. and Rastogi, S.

Does Competition Affect Shareholder Activism and Institutional Investors Used as Moderators?.

DOI: 10.5220/0013237900004646

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Cognitive & Cloud Computing (IC3Com 2024), pages 68-75

ISBN: 978-989-758-739-9

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

SHA (Anabtawi and Stout, 2007) there are pieces of

literature that highlight the need for greater

managerial accountability to the firm shareholders to

improve the performance of the firm (Dimitrov &

Jain, 2011; Bebchuk, 2007; Lan & Heracleous, 2010)

have supported the fact that increasing SHA will lead

to shareholder empowerment, which may result in the

compounding of managerial self-serving with

shareholder self-serving. Exercising management

control may also be negatively affected by the

presence of large shareholders (Cornelli & Li, 1997).

Many of the other studies, Artiga González and

Calluzzo (2019) and Bebchuk and Jackson Jr (2012),

have highlighted the concerns of the private benefit

of the shareholder groups on the cost of other

shareholders. There are twofold opinions on SHA,

one states that director nomination done through the

involvement of large investors will benefit all

investors, and the other one states that it will benefit

some of the shareholders at the cost of others (Ranova

& Ryan, 2015). Lack of skills and experience to

improve upon the manager’s decision and myopic

focus on the short-term earnings inimical to the firm’s

financial health in the long term (Wohlstetter, 1993).

Amidst a contentious and multifaceted discourse,

shareholder activism (SHA) emerges as a burgeoning

concern for economies in development. Within the

context of an emerging economy such as India, SHA

is observed to be in its formative phase (Shingade &

Rastogi, 2020). The significance and repercussions of

SHA exhibit variance across nations due to divergent

legal frameworks and levels of income inequality

(

Judge et al., 2010). Consequently, the effects of SHA

vary among firms operating within different national

jurisdictions.

Extensive literature is available, highlighting the

involvement of social issues (

King & Gish, 2015)

political connotations (Goranova & Ryan, 2014), and

environmental issues (

Perrault & Clark, 2016; Yang et

al., 2018) in the context of SHA. Instead of providing

financial benefits, SHA shows concerns related to

these issues, which puts an extra burden of cost to the

firm, as firms have to react to these issues raised

through SHA. A firm operating in the market will

always aim to increase the firm’s performance year

by year. These efforts of the firm indirectly lead to

shareholder wealth maximization (Denis, 2016;

Dobson, 1999). Striving towards reaching a position

where the shareholder wealth is maximized

optimally, leads a firm or bank to achieve the edge

over its competitors.

Market comp. is something that a firm should always

look forward to, and in the era of SHA, it becomes of

utmost importance for firms to keep both eyes on their

competitors. Thus, the primary purpose of the

research is to discover the impact of comp, on the

SHA. Putting all the best efforts into delivering the

offerings (goods/services) to the customers is the best

way through which the firm can do good for

themselves as well as for everybody else (Parmar et

al., 2010; Wright, 2001). The phenomenon this paper

is exploring is in the direction of further development

in the field of established SHA and putting light on its

relation with the comp. This paper explores this

relationship in the moderation effect of Institutional

Investors (ii).

2 REVIEW OF LITERATURE

AND HYPOTHESIS

DEVELOPMENT

The research aims to assess the effect of comp. on

the SHA, the literature on the topic deals with the

impact of comp. on the different domains of SHA.

The first opportunity to submit the shareholder

resolution in 1942 (Reid & Toffel, 2009) and the

naming of individual investors as “corporate

gadflies” in 1970 were the two main foundations of

the SHA stage (Gillan and Starks, 2007). Financial

activism, because of its more prominent impact on the

firm’s performance Thomas and Cotter (2007); Gillan

and Starks (2007). has got a big push through the rise

of institutional ownership.

In the 1990s, labor union funds became more

prominent sponsors of governance proposals by

replacing the public pension funds (Agrawal, 2012),

and at the same time, traditionally subtle mutual funds

joined the stage of activism (Brandes et al., 2008).

The prime focus of these activists is to render the

managers more accountable to shareholders and

promote governance-based financial activism (Gillan

and Starks, 2007); (Gillan & Starks, 2000). In

developed nations SHA has come in the spotlight

through the activities of the ii (Gillan & Starks, 2000;

Proffitt Jr and Spicer, 2006) especially the hedge

funds (Cheffins and Armour, 2011)

Managerial labor in the firm is exposed to many

monitoring mechanisms managers are expected to

direct the company in a way that maximizes firm

value. Several literatures are available that highlight

the connection between managers' efficiency in

dealing with threats and its impact on shareholder

wealth (Gompers et al., 2003). Second, the insights

these studies give are further extended by the degree

of comp. among industries, complementing the CG

mechanism in motivating and aligning the managers

Does Competition Affect Shareholder Activism and Institutional Investors Used as Moderators?

69

to put on their best efforts (Giroud & Mueller, 2010).

The operating performance of a firm has a significant

association with the SHA (Goranova & Ryan, 2014).

There is literature evidence available that shows that

there is a positive (Hadani et al., 2011) and negative

(Prevost and Rao, 2000) impact of SHA on the

operating performance of the firms. Just like the

association with operating performance, SHA’s

association with firm value also has twofold evidence

from the literature. Studies like (Alexander et al.,

2010; Cai & Walkling, 2011) show that SHA paves

the path for a better firm value, whereas (Clifford,

2008; Edmans, 2014) showed the other side of the

story and concluded that SHA cut back the firm’s

value. Comp. among industries helps in reducing

managerial slack and promotes opportunistic

behavior, because of these positive impacts, business

comp. as a governance maneuver has its significance

in the economic market. SHA is more likely to occur

in industries in which companies compete with very

few companies for market share because of industry

comp. is a kind of mechanism that cannot be altered

by the shareholders (Bauer et al., 2010)

A shareholder proposal can be seen as a catalyst

to the process of strengthening the control over

corporations or pressuring the management for

beneficial changes [46]. This sort of proposal

increases an activist investor’s influence on important

corporate issues and firm policies indirectly. The time

between 1997 and 2006 has witnessed an increasing

trend in shareholder proposals. Companies belonging

to the less competitive industry and with poor

governance are among the highest recipients of

shareholder proposals (Bauer et al., 2010). Apart

from being a shareholder, institutional investors play

a vital role as proposal sponsor (Gillan & Starks,

2000). These investors have more power to influence

other shareholders to use their rights and vote with

them. This is the reason that the proposals which are

sponsored by institutional investors, get strong voting

support from the shareholders. Institutional investors

seem to be more active in the issues related to the

change in management, corporate policies, and

governance structure of the firm (Chidambaran &

Woidtke, 1999). As compared to other developed

nations, SHA is in its early stage in India (Shingade

et al., 2022). The slow pace of development at SHA

can be attributed to the fact that in the past, hostile

takeover attempts and the division of ownership and

management were almost unheard of in India. Apart

from these two, scattered or inactive institutional

investors as shareholder was also one of the major

reasons (Sridhar, 2016)

The last few years have been marked as watershed

years in the context of SHA in India because of the

changes in the regulation and legislation regarding

SHA, international investors are entering the

shareholder's arena of Indian firms (Sarkar & Sarkar,

2000; Varottil, 2009). and the major milestone is the

introduction of The Companies Act, 2013 (Aggarwal

et al., 2022). The steps taken by the regulatory body

SEBI (Security Exchange Board of India) have also

polished the horn of the shareholders, allowing ballet

voting, and allowing intermediation by international

institutional shareholder groups are some of the major

reforms among them (Sridhar, 2016; Sarkar & Sarkar,

2000; Varottil, 2009). The majority of the research

that has already been written about shareholder

activism (SHA) has focused on making deductions

about the variables that affect the probability of

receiving proposals and the results of the subsequent

votes (Gillan & Starks, 2000; John & Klein, 1995;

Gordon and Pound, 1993). To the best of our

knowledge, though, no earlier studies have looked

closely at how pay (comp.) affects SHA, especially

when institutional investors are acting as a

moderating force.

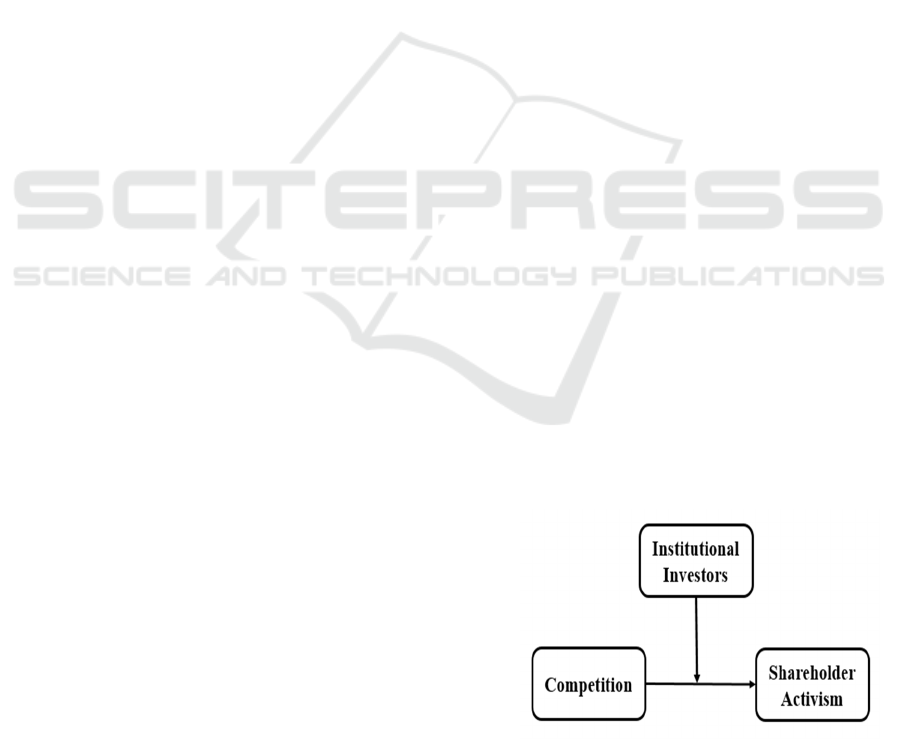

Based on the above discourse, it can be inferred

that remuneration exerts a noteworthy influence on

the direction of shareholder activism. Interestingly,

no research has been done to date on how

compensation affects SHA. In order to set itself apart,

this study analyses how remuneration affects SHA

while accounting for institutional investors'

moderating influence. As a result, the subsequent

theory is proposed for the study.

H

1

: comp. significantly affects the SHA

H

2

: Institutional Investors significantly affects the

Comp. and SHA

Fig. 1. Conceptual Model.

Source: Authors' own creation

IC3Com 2024 - International Conference on Cognitive & Cloud Computing

70

3 DATA AND METHODOLOGY

This section explains the source of data and

methodology used to understand the effect of

competition on the SHA using ii as a moderator.

3.1 Sample and data

The S&P BSE 100 Index includes 78 non-financial

Indian companies that make up the study sample. The

time frame of the study is from 2016 to 2020. In this

work, panel data regression which is defined as a

blend of cross-sectional and time-series data is

utilised to improve the overall comprehension of the

dataset. This study's use of panel data regression

makes it possible to estimate results and findings

more precisely, enhancing the analysis and making it

more perceptive using Python. The dataset includes

390 company-year data points that cover the

performance of 78 companies over the course of five

years from the perspective of econometric analysis.

Remarkably, just 78 of the 100 S&P BSE-listed

businesses were considered the best candidates for

this study's inclusion. The Centre for Monitoring

Indian Economy (CMIE) prowess and the annual

reports of these corporations provided further data for

this study.

3.2 Methodology

This study used two models (base and interaction

model) represented by equations (eq) 1 and 2.

SHA

it

= β0 + β1ln_comp + β2ln_mcap + u

it

(1)

SHA

it

= β0 + β1 ln_comp+ β2 ln_ii + β3

i_ln_Comp*ln_ii + β3 ln_mcap + u

it

(2)

Where SHA stands for shareholder activism, this is

the independent variable in the present study.

Furthermore, β0 is the constant term, and ln_comp

stands for comp. and represents the comp. level

between the company, this is the independent

variable. Ln_ii denotes the institutional investor.

i_ln_Comp*ln_ii represents the interacting term.

ln__mcap is the log of market capitalization. It is used

as the control variable in the calculation. Lastly, u

it

considered to be an incorrect term. Within the Table.

In this study, the variables are defined and employed.

Table 1: Variable.

Variable

s

Ty

p

e

Definition Citation

SHA DV

The use of an

ownership position to

effect business policies and

practices is known as

shareholder activism.

Judge et

al. (2010)

and Rose

and

Sharfman

(2014)

ln_comp EV

The customer-focused

approach of banks is

always analyzed in terms of

comp..

Karpoff et

al. (1996)

ln_ii

M

V

It signifies the

investment made by the

institutional investo

r

Anabtawi

and Stout,

(2007)

ln_mcap CV

It is determined by

multiplying the share's

current market value by the

number of the corporation's

outstandin

g

shares.

Shingade

&

Rastogi,

(2020)

Note: Define the variable of stud

y

4 RESULTS

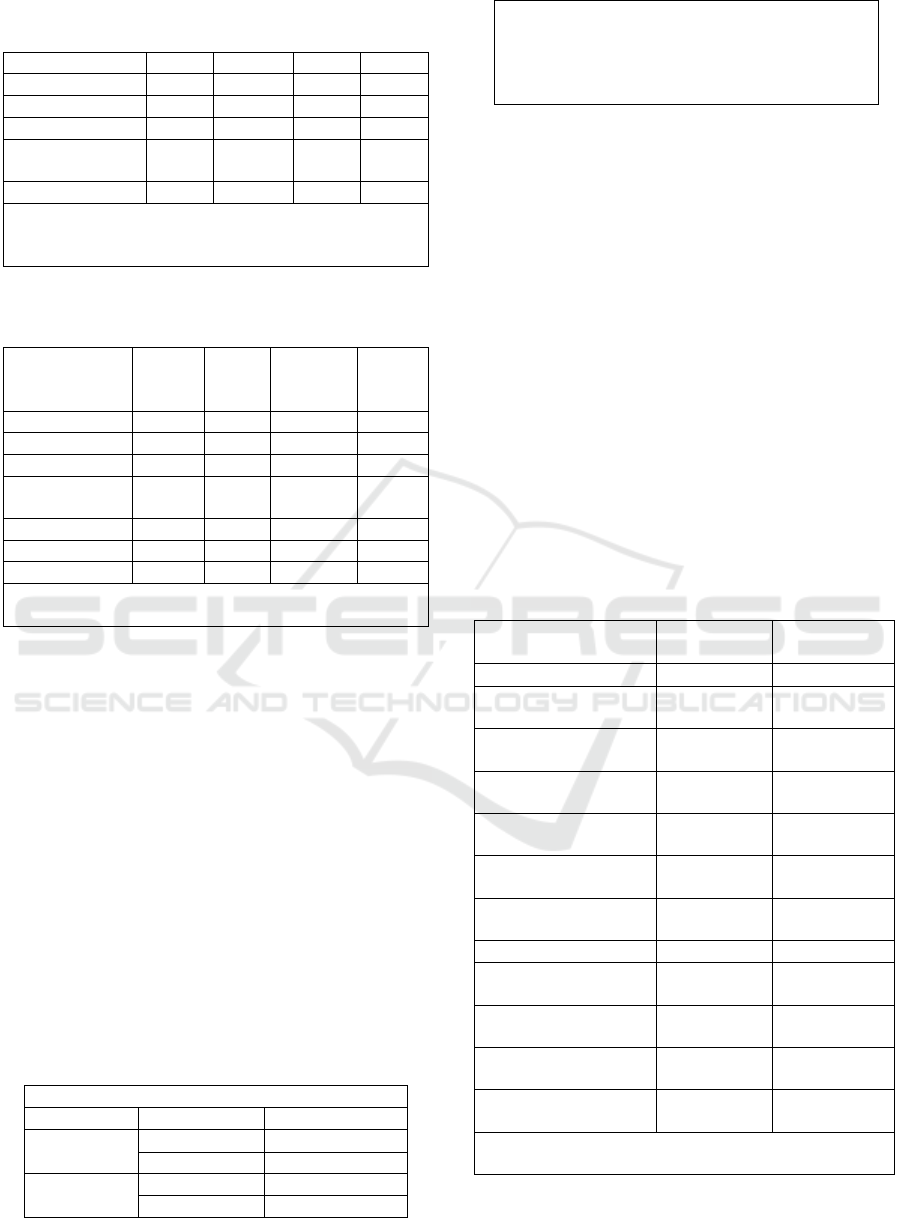

This section explains the descriptive statistics and

multicollinearity issue of the variables. Additionally,

the regression result is explained to understand the

relationship between them.

4.1 Descriptive Statistics and

Correlation

Table 2 represents the descriptive statistics of the

study. The mean value of SHA is 0.675, which

somewhere lies between the min and max values. It

implies a moderate level of shareholders are active in

the company. The standard deviation is 0.066 implies

that the variation in SHA-level activities between

companies is very low. ln_comp average value is -

1.571 lies more toward the max level implying a

higher level of comp. between companies. The

variation of comp. between companies is at a

moderate level as the standard deviation of ln_comp

is 1.442. the ln_ii mean value is 3.473 lies more

toward the max level.

Table 3 comprehensive relationships between the

independent and control variables are outlined in the

correlation matrix. Interestingly, it is apparent that

there are no examples of statistically insignificant

correlations larger than 0.8. This discovery strongly

implies that there are no problems with

multicollinearity in the dataset.

Does Competition Affect Shareholder Activism and Institutional Investors Used as Moderators?

71

Table 2: Descriptive Statistics.

Source: Python Outcome

Table 3: Correlation Matrix.

Variables ln_com

p

lnii i_ln_Com

p

*ln_ii

ln_mca

p

ln

_

com

p

1.000

ln

_

ii -0.093 1.000

(

0.066

)

i_ln_Comp*ln

_

ii

0.989* -0.202* 1.000

(

0.000

)

(

0.000

)

ln

_

mca

p

0.138* -0.123* 0.137* 1.000

(0.006) (0.015) (0.006)

Note: A significant correlation coefficient at 0.05 is

indicated b

y

the s

y

mbol *

Source: Python Outcome

4.2 Endogeneity Results

The endogeneity test results are shown in Table 4.

The base model the Durbin Chi-2 p-value is 0.7469,

and the Wu-Hausman test produces a p-value of

0.7504. Both values are greater than the traditional

significance level of 0.05, which suggests that

endogeneity problems have been resolved and

indicates that there are no statistically significant

results. In the same way, the interaction term's Durbin

Chi-2 p-value is 0.3789, and the Wu-Hausman test

produces a p-value of 0.3884, both of which are

higher than 0.05, confirming the results' lack of

significance and proving there are no endogeneity

issues.

Table 4: Endogeneity Results.

DV: SHA

lnComp lnComp_lnii

Durbin Chi-2 .104191 .774415

(0.7469) (0.3789)

Wu-Hausman

Test

.101587 .748176

(0.7504) (0.3884)

Note: An asterisk (*) denotes a statistically

significant value at a significance level of 5%. The

value enclosed in parentheses represents the p-

value. In this context, SHA represents the

endogenous variable.

Source: Python Outcome

4.3 Regression Results

Table 5. represent the base and interaction model. In

the base model, the association between comp. and

shareholder activism is seen. The robustness of the

result is measured as the problem of

heteroscedasticity is found as the Wald test is

significant, having a p-value of 0.000. the problem of

autocorrelation is insignificant as the p-value of the

Woolridge test is 0.5745. the coefficient of ln_comp

is -0.004 having a p-value (<0.05) is statistically

significant implying that the comp. is negatively

associated with the SHA as an increase in the comp.

leads to a rise in the SHA of the company. In the

Interaction model, the coefficient of i_ln_Comp*ln_ii

is 0.001, and having a p-value more than 0.05, it

implies that there is no impact of moderator ii on the

comp. and SHA of the company.

Table 5: Results of Regression.

DV: SHA Base model

Interaction

model

Coef. Coef.

ln_comp

-.004*

(

.001

)

-.010

(

.022

)

ln_ii

.105*

(.016)

i_ln_Comp*ln_ii

.001

(.006)

ln_mcap

.018*

(

.005

)

.012**

(

.005

)

Cons

.469*

(.059)

.165**

(.079)

BP-test (Random

effect)

472.56

(0.000)

442.26

(0.000)

Hausman Test

0.53 (0.765) 30.46 (0.000)

F- test

22.53*

(0.000)

Chi- square

18.82*

(0.000)

Wald test chi2

25689.01*

(

0.000

)

35298.56*

(

0.000

)

Wooldridge test

0.318

(0.574)

0.023

(0.880)

Notes: * and ** indicates a significant value at a 5%

and 10% respectively.

Source: Python Outcome

Variable Mean Std.Dev. Min Max

SHA 0.675 0.066 0.459 0.810

ln

_

com

p

-1.571 1.442 -7.844 1.456

ln

_

ii 3.473 0.390 1.964 4.374

i_ln_Comp*ln_i

i -5.514 5.218 -28.636 5.157

ln

_

mca

p

10.933 0.935 8.890 13.832

Note: The terms mean, SD, Min, and Max refer to the

mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum

values, in that order.

IC3Com 2024 - International Conference on Cognitive & Cloud Computing

72

4.4 Robustness of the Result

The results shown in Table 5 show that the outcomes

from the two models are consistent with one another.

Robustness tests were carried out to verify these

findings.

The underlying model's autocorrelation turned out to

be a problem, thus robustness tests were conducted to

solve it. Furthermore, the interaction model

demonstrated signs of heteroscedasticity and

autocorrelation, requiring additional robustness

testing to address these issues.

5 DISCUSSION

This study's main goal is to find out how

comp. affects SHA. The foundational model's results

are consistent with the first hypothesis (HI), which

states that comp. and SHA are negatively correlated.

This implies that increased shareholder action follows

a rise in comp. On the other hand, the findings of the

succeeding model show that moderator ii has no

discernible impact on the association between

SHA and comp., hence refuting the second

hypothesis (H2). The findings are inconsistent with

those of (Bauer et al., 2010)whose findings state that

in the absence of fierce comp. in the industry,

companies are more likely to be targeted by

shareholders. This difference may be attributed to the

studies being done in different nations, one being the

developed and other being developing. The results of

the study are consistent with the (Allen et al. 2007),

which states that shareholders-driven firms benefit

from the comp. This shows that the level of comp. not

only increases the SHA but also positively affects the

firm's value.

6 CONCLUSION

The prime objective of this paper is to evaluate the

effect of comp. on SHA, which can highlight the

dependence of SHA on comp. The study's two-

dimensional goal has been achieved by adding ii as a

moderating element. The study demonstrates how

SHA, ii, and comp. are related. The limitation of the

study is that the ii are used only as a single moderator,

the impact of other moderators remains unobserved.

Based on the study's findings we recommend more

efforts be taken to strengthen the SHA in developing

economies like India. Companies’ management may

not appreciate SHA, as they consider this as an

additional waste of time and money, but to implement

CG in its true sense, SHA can play an important role.

REFERENCES

David, P., Bloom, M., & Hillman, A. J. (2007). Investor

activism, managerial responsiveness, and corporate

social performance. Strategic Management Journal,

28(1), 91–100.

Judge, W. Q., Gaur, A., & Muller‐Kahle, M. I. (2010).

Antecedents of shareholder activism in target firms:

Evidence from a multi‐country study. Corporate

Governance: An International Review, 18(4), 258–273.

Rose, P., & Sharfman, B. S. (2014). Shareholder activism

as a corrective mechanism in corporate governance.

BYU Law Review, 1015.

Wahal, S. (1996). Pension fund activism and firm

performance. Journal of Financial and Quantitative

Analysis, 31(1), 1–23.

Karpoff, J. M., Malatesta, P. H., & Walkling, R. A. (1996).

Corporate governance and shareholder initiatives:

Empirical evidence. Journal of Financial Economics,

42(3), 365–395.

Goranova, M., & Ryan, L. V. (2014). Shareholder activism:

A multidisciplinary review. Journal of Management,

40(5), 1230–1268.

Thomas, R. S., & Cotter, J. F. (2007). Shareholder

proposals in the new millennium: Shareholder support,

board response, and market reaction. Journal of

Corporate Finance, 13(2–3), 368–391.

Bebchuk, L. A. (2005). The case for increasing shareholder

power. Harvard Law Review, 118(833), 880–884.

Reid, E. M., & Toffel, M. W. (2009). Responding to public

and private politics: Corporate disclosure of climate

change strategies. Strategic Management Journal,

30(11), 1157–1178.

Rehbein, K., Waddock, S., & Graves, S. B. (2004).

Understanding shareholder activism: Which

corporations are targeted? Business & Society, 43(3),

239–267.

Rosenberg, H. (1999). A traitor to his class: Robert AG

Monks and the battle to change corporate America.

John Wiley & Sons.

Anabtawi, I., & Stout, L. (2007). Fiduciary duties for

activist shareholders. Stanford Law Review, 60, 1255.

Dimitrov, V., & Jain, P. C. (2011). It’s showtime: Do

managers report better news before annual shareholder

meetings? Journal of Accounting Research, 49(5),

1193–1221.

Bebchuk, L. (2007). The myth of the shareholder franchise.

Virginia Law Review, 93, 833–835.

Lan, L. L., & Heracleous, L. (2010). Rethinking agency

theory: The view from law. Academy of Management

Review, 35(2), 294–314.

Cornelli, F., & Li, D. D. (1997). Large shareholders, private

benefits of control, and optimal schemes of

privatization. Rand Journal of Economics, 28(4), 585–

604.

Does Competition Affect Shareholder Activism and Institutional Investors Used as Moderators?

73

González, T. A., & Calluzzo, P. (2019). Clustered

shareholder activism. Corporate Governance: An

International Review, 27(3), 210–225.

Bebchuk, L. A., & Jackson, R. J. Jr. (2012). The law and

economics of blockholder disclosure. Harvard

Business Law Review, 2, 39.

Goranova, M., & Ryan, L. V. (2015). Shareholder

empowerment: An introduction. In Shareholder

empowerment: A new era in corporate governance (pp.

1–32). Springer.

Wohlstetter, C. (1993). Pension fund socialism: Can

bureaucrats run the blue chips? Harvard Business

Review, 71(1), 78.

Shingade, S. S., & Rastogi, S. (2020). Issues raised by

activist shareholders: A review of literature. Test

Engineering and Management, 83(May-June), 9891–

9897.

King, L., & Gish, E. (2015). Marketizing social change:

Social shareholder activism and responsible investing.

Sociological Perspectives, 58(4), 711–730.

Perrault, E., & Clark, C. (2016). Environmental shareholder

activism: Considering status and reputation in firm

responsiveness. Organization & Environment, 29(2),

194–211.

Yang, A., Uysal, N., & Taylor, M. (2018). Unleashing the

power of networks: Shareholder activism, sustainable

development, and corporate environmental policy.

Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(6), 712–

727.

Denis, D. (2016). Corporate governance and the goal of the

firm: In defense of shareholder wealth maximization.

Financial Review, 51(4), 467–480.

Dobson, J. (1999). Is shareholder wealth maximization

immoral? Financial Analysts Journal, 55(5), 69–75.

Parmar, B. L., Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., Wicks, A. C.,

Purnell, L., & De Colle, S. (2010). Stakeholder theory:

The state of the art. Academy of Management Annals,

4(1), 403–445.

Wright, P. (2001). Do you know your stakeholders?

Fostering good company stakeholder relationships is a

great way to nurture a positive corporate reputation.

Strategic Communication Management, 5(5), 14–19.

Reid, E. M., & Toffel, M. W. (2009). Responding to public

and private politics: Corporate disclosure of climate

change strategies. Strategic Management Journal,

30(11), 1157–1178.

Gillan, S., & Starks, L. T. (2007). The evolution of

shareholder activism in the United States. Journal of

Applied Corporate Finance, 19(1), 55–73.

Agrawal, A. K. (2012). Corporate governance objectives of

labor union shareholders: Evidence from proxy voting.

Review of Financial Studies, 25(1), 187–226.

Brandes, P., Goranova, M., & Hall, S. (2008). Navigating

shareholder influence: Compensation plans and the

shareholder approval process. Academy of Management

Perspectives, 22(1), 41–57.

Gillan, S. L., & Starks, L. T. (2000). Corporate governance

proposals and shareholder activism: The role of

institutional investors. Journal of Financial Economics,

57(2), 275–305.

Proffitt, W. T., Jr., & Spicer, A. (2006). Shaping the

shareholder activism agenda: Institutional investors and

global social issues. Strategic Organization, 4(2), 165–

190.

Cheffins, B. R., & Armour, J. (2011). The past, present, and

future of shareholder activism by hedge funds. Journal

of Corporate Law, 37, 51.

Gompers, P., Ishii, J., & Metrick, A. (2003). Corporate

governance and equity prices. Quarterly Journal of

Economics, 118(1), 107–156.

Giroud, X., & Mueller, H. M. (2010). Does corporate

governance matter in competitive industries? Journal of

Financial Economics, 95(3), 312–331.

Hadani, M., Goranova, M., & Khan, R. (2011). Institutional

investors, shareholder activism, and earnings

management. Journal of Business Research, 64(12),

1352–1360.

Prevost, A. K., & Rao, R. P. (2000). Of what value are

shareholder proposals sponsored by public pension

funds? The Journal of Business, 73(2), 177–204.

Alexander, C. R., Chen, M. A., Seppi, D. J., & Spatt, C. S.

(2010). Interim news and the role of proxy voting

advice. Review of Financial Studies, 23(12), 4419–

4454.

Cai, J., & Walkling, R. A. (2011). Shareholders’ say on pay:

Does it create value? Journal of Financial and

Quantitative Analysis, 46(2), 299–339.

Clifford, C. P. (2008). Value creation or destruction? Hedge

funds as shareholder activists. Journal of Corporate

Finance, 14(4), 323–336.

Edmans, A. (2014). Blockholders and corporate

governance. Annual Review of Financial Economics,

6(1), 23–50.

Bauer, R., Braun, R., & Viehs, M. (2010). Industry

competition, ownership structure, and shareholder

activism. Ownership Structure and Shareholder

Activism (September 16, 2010).

Karpoff, J. M. (2001). The impact of shareholder activism

on target companies: A survey of empirical findings.

Available at SSRN 885365.

Chidambaran, N. K., & Woidtke, T. (1999). The role of

negotiations in corporate governance: Evidence from

withdrawn shareholder-initiated proposals. European

Finance Association, 458, 12–99.

Shingade, S., Rastogi, S., & Panse, C. (2022).

Shareholders’ activism in India: Understanding

characteristics of companies targeted by activist

shareholders using discriminant analysis. In 2022 IEEE

Technology and Engineering Management Conference

(TEMSCON EUROPE) (pp. 94–99). IEEE.

Sridhar, I. (2016). Corporate governance and shareholder

activism in India—Theoretical perspective. Theoretical

Economics Letters, 6(4), 731.

Sarkar, J., & Sarkar, S. (2000). Large shareholder activism

in corporate governance in developing countries:

Evidence from India. International Review of Finance,

1(3), 161–194.

Varottil, U. (2009). The advent of shareholder activism in

India. Journal on Governance, 1, 582.

IC3Com 2024 - International Conference on Cognitive & Cloud Computing

74

Aggarwal, M., Chakrabarti, A. S., & Dev, P. (2020).

Breaking ‘bad’ links: Impact of Companies Act 2013

on the Indian corporate network. Social Networks, 62,

12–23.

John, K., & Klein, A. (1995). Shareholder proposals and

corporate governance.

Gordon, L. A., & Pound, J. (1993). Information, ownership

structure, and shareholder voting: Evidence from

shareholder‐sponsored corporate governance

proposals. Journal of Finance, 48(2), 697–718.

Bauer, R., Braun, R., & Viehs, M. (2010). Industry

competition, ownership structure, and shareholder

activism. Ownership Structure and Shareholder

Activism (September 16, 2010).

Allen, F., Carletti, E., & Marquez, R. (2007). Stakeholder

capitalism, corporate governance and firm value.

Corporate Governance and Firm Value (September 16,

2009). EFA, 09-28.

Does Competition Affect Shareholder Activism and Institutional Investors Used as Moderators?

75