A Value-Driven Approach to the Online Consent Conundrum: A Study

with the Unemployed

Paul van Schaik and Karen Renaud

Teesside University, University of Strathclyde, U.K.

Keywords:

Values, Value Creators, Consent Forms, Unemployed.

Abstract:

Online services are required to gain informed consent from users to collect, store and analyse their personal

data, both intentionally divulged and derived during their use of the service. There are many issues with these

forms: they are too long, too complex and demand the user’s attention too frequently. Many users consent

without reading so do not know what they are agreeing to. As such, granted consent is effectively uninformed.

In this paper, we report on two studies we carried out to arrive at a value-driven approach to inform efforts

to reduce the length of consent forms. The first study interviewed unemployed users to identify the values

they want these forms to satisfy. The second survey study helped us to quantify the values and value creators.

To ensure that we understood the particular valuation of the unemployed, we compared their responses to

those of an employed demographic and observed no significant differences between their prioritisation on any

of the values. However, we did find substantial differences between values and value creators, with effort

minimisation being most valued by our participants.

1 INTRODUCTION

The requirement for mandating informed consent to

permit online data gathering and processing inherits

the paradigm from the fields of medicine and research

(Beauchamp, 2011). Legislation such as the European

Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

forces online service providers to ask users to con-

sent to collection, storage and processing of their data.

There are, unfortunately, many reasons for the failure

of this mechanism to obtain truly informed consent.

Solove (2012, p. 1888) writes that “consent is not

meaningful in many contexts involving privacy” be-

cause “(1) people do not read privacy policies; (2) if

people read them, they do not understand them; (3)

if people read and understand them, they often lack

enough background knowledge to make an informed

choice; and (4) if people read them, understand them,

and can make an informed choice, their choice might

be skewed by various decision making difficulties”.

Solove is suggesting that people are not granting in-

formed consent. Users cope with the frequent unus-

able consent forms they encounter by dismissing them

(without reading them) (Parfenova et al., 2024). This

means that consent forms, in general, do not fulfil

their core purpose (Chomanski and Lauwaert, 2023).

The length of privacy policies deters online users from

engaging with them (McDonald and Cranor (2008)),

given the effort required. If the length can be reduced,

it would likely mitigate the situation, but such short-

ening must be done mindfully. One way to do so is

to ensure that the forms provide only the information

that satisfies users’ values. As yet, we do not know

what these values are, and in the absence of this, con-

sent forms strive towards comprehensive coverage of

all information. We identified these values by inter-

viewing unemployed users. Having derived a set of

values from a qualitative analysis, we carried out a

second study to determine how users (specifically our

target users, the unemployed) would comparatively

rate the derived values (Section 2). Section 3 reports

on our findings.

2 METHOD

2.1 Research Questions and Study

Design

We conducted two studies, with the following re-

search questions and designs. Study 1: What are the

informed consent-related values and value creators

for the unemployed? A laddering interview design

van Schaik, P. and Renaud, K.

A Value-Driven Approach to the Online Consent Conundrum: A Study with the Unemployed.

DOI: 10.5220/0013083300003899

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2025) - Volume 1, pages 133-140

ISBN: 978-989-758-735-1; ISSN: 2184-4356

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

133

(Dolan, 1989) was used to elicit values and value cre-

ators that contribute to informed consent in the con-

text of online services. The output of the study was a

hierarchical set of values and value creators. We also

measured privacy literacy (Trepte et al., 2015).

Study 2: How do unemployed people weight the val-

ues and value creators in the informed consent con-

text, and how do these differ from the way the em-

ployed rank these?

A two-group independent measures design was

used. The groups were unemployed and employed

people. The output of the study was a quantified hi-

erarchical structure of values and value creators with

value and value-creator weightings separate for em-

ployed vs unemployed participants.

2.2 Participants

Studied Demographic. We chose to focus on values

of the unemployed, and their experiences in engag-

ing with online consent forms. Seabright (2010) ex-

plains that the unemployed inhabit ‘information is-

lands’. Unlike the employed who benefit from regular

security awareness training, there are no bridges for

the unemployed to gain up-to-date information. This

means that it is easy for misunderstandings to gain

traction because people are out of touch with the latest

security advice. Seabright says that society does not

construct bridges to increasingly isolated unemployed

communities. The cyber security field is dynamic and

fluid due to the sustained and inventive efforts of cy-

ber criminals. This demographic is thus more vulner-

able to losing their privacy. Moreover, declining to

give consent might be infeasible if monetary rewards

are dependent on consent, perhaps more likely a pres-

sure point for the unemployed.

Study 1. Thirteen unemployed participants re-

sponded to an invitation from a previous study

(Van Schaik et al. (2024)). They were compensated

for their time through a voucher or a SIM card 30 gi-

gabytes of free data to use on their smartphone.

Study 2. One hundred and two unemployed par-

ticipants and the same number of employed partic-

ipants, 115 female (68 unemployed, 47 employed)

and 89 male (34 unemployed, 55 employed), were re-

cruited through via an online survey panel and com-

pensated for their time according to the panel’s rate.

Their mean age was 52 (SD = 15).

2.3 Materials

Study 1. A laddering interview guide was created and

used. Two scales were used: the Online Privacy Lit-

eracy Scale (OPLIS) (Trepte et al., 2015) was used to

measure specific privacy knowledge. (Details of our

OPLIS scoring scheme are presented under Study 2,

as the development of this scheme required a larger

sample than that of Study 1.) In this sample the mean

was 12.92 (SD =3.12), which corresponds to approx-

imately a 57 percentile rank according to Masur et al.

(2017).

Study 2. An AHP survey was created according to

guidelines for survey construction (Dolan et al., 1989;

Dolan, 2008), using the output of Study 1 (a hierarchy

of values and value creators) as input. All the possi-

ble pairs of values underlying the higher-order goal

of informed consent were formed as well as all the

possible pairs of value creators underlying each value.

The collective pairs were presented sequentially (first

the value pairs [randomised] and then the value cre-

ator pairs for each value [values randomised; value

creator pairs randomised within values]). Participants

had to evaluate the relative importance within each

pair (for example, the importance of the value of con-

trol relative to that of fairness). As in Study 1, OPLIS

measured privacy literacy. The Affinity for Technol-

ogy Interaction scale (ATI) measured “the tendency to

actively engage in intensive technology interaction”

(Franke et al., 2019, p. 456).

2.4 Procedure

Study 1. Because of pandemic restrictions and to

reach a geographically UK-wide audience, interviews

were conducted remotely by VoIP or by telephone,

recorded and automatically transcribed. Afterwards,

the recordings were played back and any corrections

were made to the transcripts. In each interview, the

participant was asked to identify value creators (what

an online consent form should provide) and subse-

quently for each value creator one or more values

(why the value creator is important). Interviews lasted

from 14 to 34 minutes. After each interview, the par-

ticipant was directed to an online survey to complete

OPLIS.

Study 2. Participants were directed to an online

survey that administered demographic questions, a se-

ries of AHP pairwise comparisons, OPLIS and the

ATI scale.

Ethics. Research ethics approval was ob-

tained from the University of Strathclyde and from

REPHRAIN, National Research Centre on Privacy,

Harm Reduction and Adversarial Influence Online.

2.5 Data Analysis

Study 1. We used the framework of means-ends chain

analysis to identify people’s needs (value) and how

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

134

these could be achieved (value creators) (Kilwinger

and van Dam, 2021). Both researchers coded an ini-

tial set of five transcripts. Their individual coding

schemes were discussed and a final coding scheme

was agreed. One of the authors then coded all the

transcripts.

Study 2. AHP analysis of response consistency

and weightings was conducted (Dolan et al., 1989).

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) techniques were used

to analyse differences between unemployed and em-

ployed participants on the AHP weightings.

3 FINDINGS

3.1 OPLIS & ATI

The original OPLIS has four dimensions to mea-

sure online privacy literacy: institutional practices,

technical aspects of data protection, data protection

law, and data protection strategies. As explained by

Edelsbrunner (2022), knowledge in different domains

are often best assessed with formative measurement.

Therefore, we created a measure consisting of items

from each of these four dimensions. From each di-

mension, we selected two items, based on the percent-

age of the sample that answered correctly: between 25

pct and 50 pct, the item with the minimum correct-

ness and, between 50 pct and 75 pct, the item with

the maximum correctness. This procedure ensured an

equal mix of more difficult and easier items. A t test

showed that online privacy literacy did not differ be-

tween employed (M = 56.86; SD = 23.57) and unem-

ployed (M = 53.19; SD = 20.79) participants, t = 1.18,

df = 198.89, p = 0.24, d = 0.17.

Factor analysis of the Study 2 data was conducted

on the ATI and produced a one-factor solution, with

56 pct of variance explained. Factor scores were cal-

culated and used in subsequent analysis. A t test

showed that affinity for technology interaction was

higher in employed (M = 0.14; SD = 1.02) than in

unemployed (M = -0.18; SD = 0.91) participants, t =

2.84, df = 199.31, p = 0.005, d = 0.40.

3.2 Study 1

Study 1 sought to identify a hierarchical means-end

structure of informed consent for online services (Fig-

ure 1).

Five values were identified: (1) control, (2) un-

certainty avoidance, (3) loss aversion, (4) effort min-

imisation and (5) fairness. Under each value, two or

more value creators were identified. The value cre-

ators (means) underlying each value (end) would con-

tribute to the value. In turn, the values would con-

tribute to the higher-order goal of informed online

consent decision-making. The values and underly-

ing value creators are presented here, with illustrative

quotations, where P<number> represents a quoted

numbered participant.

3.2.1 Control

Control was defined as a user’s feeling that they have

control. Three value creators contributing to the value

of control were identified.

(1) Payment for Data (being paid for giving

data/having one’s data captured by an online service).

Participants expected to be paid for the data they

provided, but this was not often not the case: “I’m a

big fan, by the way, of this idea that they pay me for

it ... If they’re making money off it, I should get my

cut.” (P55)

(2) Access to Services (not having to sign up for cer-

tain services in order to be able to read the pages) (see

Fairness [value], Should consent be required[value

creator])

(3) Range of Choice Options (having a range

of choice options in responding to an online consent

form, for example, only the options of accept all or

reject all, or a larger set of more fine-grained options

that offers more choice).

Participants expected they would be able to select

which data will be shared: “What I want to see in

these forms is ... can I selectively choose? Alright,

you can have my location, but you can’t have some-

thing else. You can’t track me for example, as I’m

using the website.” (P26) “You see particulars, my lo-

cation or something, but I don’t remember consenting

to that.” (P26)

3.2.2 Uncertainty Avoidance

Uncertainty avoidance was defined as a user’s desire

to gain information to reduce or remove uncertainty.

Eight value creators contributing to the value of

uncertainty avoidance were identified. agree to it and

otherwise they would not offer the service.(P29)

(1) Consumers’ Rights (information about con-

sumers’ rights when they use the specific online

service that is provided).

Consumers’ rights in consent documents were

seen as beneficial for both users and service compa-

nies: “I suppose it should provide what they expect of

me and what I can expect of them.” (P56) “I would

A Value-Driven Approach to the Online Consent Conundrum: A Study with the Unemployed

135

EFFORT

MINIMISATION

Conciseness

Summary

Information

How Long

Consent Lasts

Ease of Reading

Information Clarity

UNCERTAINTY

AVOIDANCE

Attracting

Attention

Standardisation

Certification

Summary

Information

Consequences

Information

Processing

Clarity

Consumer

Rights

LOSS

AVERSION

Consequences

Risk

Information

FAIRNESS

Functionality

Legal

Protection

Should it be

Required?

CONTROL

Payment for

Data

Range Choice

Options

Access to

Services

Figure 1: Means-end hierarchy of user values and value creators contributing to informed consent decision making.

like to know what my rights are as a consumer so

if there was just a sheet of main bullet points that

probably would be better.” (P73)

(2) Information Processing (information about

what happens to the user’s personal data).

Participants expected that a consent document

would explain how their data would be stored and

be processed, and why: “Information in such a con-

sent form would include how they handle data and

privacy [and] whether they hold data on computers

in the USA.” (P33) “When information is stored or

where it is stored ” (P57)

(3) Attracting your Attention (highlighting important

information to attract a your attention). Participants

expected that critical information in a consent docu-

ment would be highlighted in order to attract users’

attention before they decided to consent: “I’m always

very of the idea that it should be clear, and if it is

very important, it should have something like a red

box around it ... should be highlighted ... the abil-

ity to follow you to other websites ... The ability to

sell the information to unknown and any third party

without either compensating me for it or asking my

permission. ” (P55)

(4) Information Clarity (how easy it is to understand

the online consent text (simplicity and comprehensi-

bility of text) [see effort minimisation].

(5) Consequences (information linked to impor-

tant consequences for the online-service user) [see

loss aversion].

(6) Standardisation (standardisation of forms

according to relevant information categories for

users).

Standardisation, together with shortening consent

documents, would also facilitate users’ reading and

understanding as a basis for making a consent deci-

sion: “If it was shorter; I think if it if it was standard-

ised so you knew what certain sentences meant and so

it was just more bullet points and you knew what that

referred to instead of it being a long complex thing all

the time.” (P77)

(7) Certification (a sign presented on the consent

form to show certification by a trusted party). Certi-

fication with icon visualization could communicate

consent information quickly and clear. “[If] it was

icons that you got used to know what they mean, like

the Facebook icons. Yes, [if] there was an icon ’we

sell your data’. [It] would just be quick when you get

used to seeing [the icon], when you know instantly

what we were signing up to.” (P77)

(8) Summary Information (summary consent

information, with links to further details, for exam-

ple, clickable icons that link to detailed information).

The expectation was that providing summary in-

formation with links to detailed information would re-

duce the required reading time to make a consent de-

cision, make it more likely that users would read the

information and cater for users with different needs in

terms of information detail: “[A] bit more streamlined

so you’ve got four options, so you don’t have to click

through. You might have the option to go through and

read more information, but you shouldn’t have to. It

should give you a brief summary of each thing that

can select.” (P83)

3.2.3 Effort Minimisation

Effort minimisation was defined as a reduction in

the effort required to process the information that

is presented. Five value creators contributing to the

value of effort minimisation were identified.

(1) Conciseness (conciseness of text, for exam-

ple, using bullet points). Concise writing in consent

documents could facilitate reading and understand-

ing: “Should follow guidance from the Plain English

Campaign. Online consent forms should be brief and

concise ... [The] benefit should be easily read and

understood in 2 to 3 minutes.” (P33)

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

136

(2) Ease of Reading (how easy it is to read the on-

line consent text, for example in terms of font size).

Text should facilitate reading, for example by use of

the sufficiently large font, but participants’ experience

was the opposite: “Should also make the type (font)

bigger. Should use normal print.” (P33)

(3) How Long Consent Lasts (one-time consent

process or consent required each time the online

service is accessed). Participants experienced the

same consent process on repeat use of the same

application, which was seen as inefficient: “I always

find it quite strange when they have to ask again.”

(P55)

(4) Information Clarity (how easy it is to un-

derstand the online consent text). Participants felt

that online consent text should be understandable

also by non-specialist users in technology and data

protection. “Someone like me who is not very techy

doesn’t really understand ... any information.” (P26)

“A bit more simple, a lot less kind of like jargon and

lingo”. (P57)

(5) Summary Information (summary consent

information, with links to further detail (for example,

clickable icons that link to detailed information) [see

Uncertainty Avoidance]

3.2.4 Fairness

Fairness was defined as a user’s feeling that their

personal rewards and costs and those of another party

are in balance with each other. Three value creators

contributing to the value of fairness were identified.

(1) Should Consent be Required? (feeling that

the user’s need for consent is in balance with the

extent of the functionality that the online service or

website provides to the user).

Participants felt that consent procedures should be

proportionate int that users’ effort should be in bal-

ance with the functionality that consent gives access

to: “But you know if all I really want to do is look at

a picture or read a very brief article, I don’t want to

read 30 pages of terms and conditions.” (P55)

(2) Functionality (feeling that the nature or volume

of personal data the user provides is in balance with

the functionality they receive from the online service

or website)

Users realised that online services often operate

a business where, as a condition for using an online

service for free of monetary change, users give their

personal data. Users consented although they did not

(fully) agree: “You make a deal with the devil. You’ve

got to pay the price. So, yeah, I’m kind of one of those

where if I want to use a service, I have to accept that

I give them my data and they use it the way they see

fit.” (P55)

(3) Legal Protection (feeling that the user’s diffi-

culty of understanding the complexity of the text is in

balance with protection that the text gives the online

service provider against legal action).

The use of specialist legal language that was chal-

lenging for users to understand was seen as unfair: “I

think it should be clear enough that you don’t have

to have done a law course at university to understand

the basics.” (P55) “It would be important to avoid

legalese in the phrasing of these standardised forms.”

(P64)

3.2.5 Loss Aversion

Loss aversion was defined as a user’s preference to

avoid losses. Two value creators contributing to the

value of loss aversion were identified.

(1) Risk Information (risk-related data and commu-

nication of potential risk). A strategy for users to

reduce risk was to stay with trusted major companies

rather than rely on consent documents: “I don’t even

look if I know a company’s name ... I tend to just

trust it anyway. So that’s why I tend to stick with the

big names of the brand.” (P57)

(2) Information about Consequences (information

linked to important risky consequences for the user).

Participants believed that about information risky

consequences of consent for online services was not

always available to or not read by users, with serious

potential consequences. In response, a strategy was

for users to reduce the personal information they gave

away: “I mean you sign up to one site and you didn’t

know but probably ... access to God knows how many

countries ... data being sold to Russia and China or

whatever exactly that they would be doing on a daily

basis without [you] knowing.” (P77)

3.3 Study 2

Study 2 sought to quantify the perceived relative im-

portance of the values and value creators identified in

Study 1.

Consistency. Consistency (of comparative judg-

ment) ratios were calculated for the top-level goal of

informed online consent from the pairwise compared

values and for each of four of the five values from the

pairwise compared values. (Consistency did not ap-

ply to the value of loss aversion, as there were two

value creators.) According to the standard cut-off for

A Value-Driven Approach to the Online Consent Conundrum: A Study with the Unemployed

137

consistency (consistency ratio, CR < 0.10) 27 pct to

36 pct of cases was consistent, and 63 pct to 69 pct

was consistent with a cut-off of 0.20.

Weightings, sensitivity analysis. Sensitivity anal-

ysis was conducted in the subsequent analysis of

weightings for values and value creators to establish

the robustness of the findings. The pattern of results

of means and confidence intervals for informed on-

line consent and each of the five values was the same

for the two cut-offs; the pattern of inferential statistics

was the same for the two cut-offs (see results below).

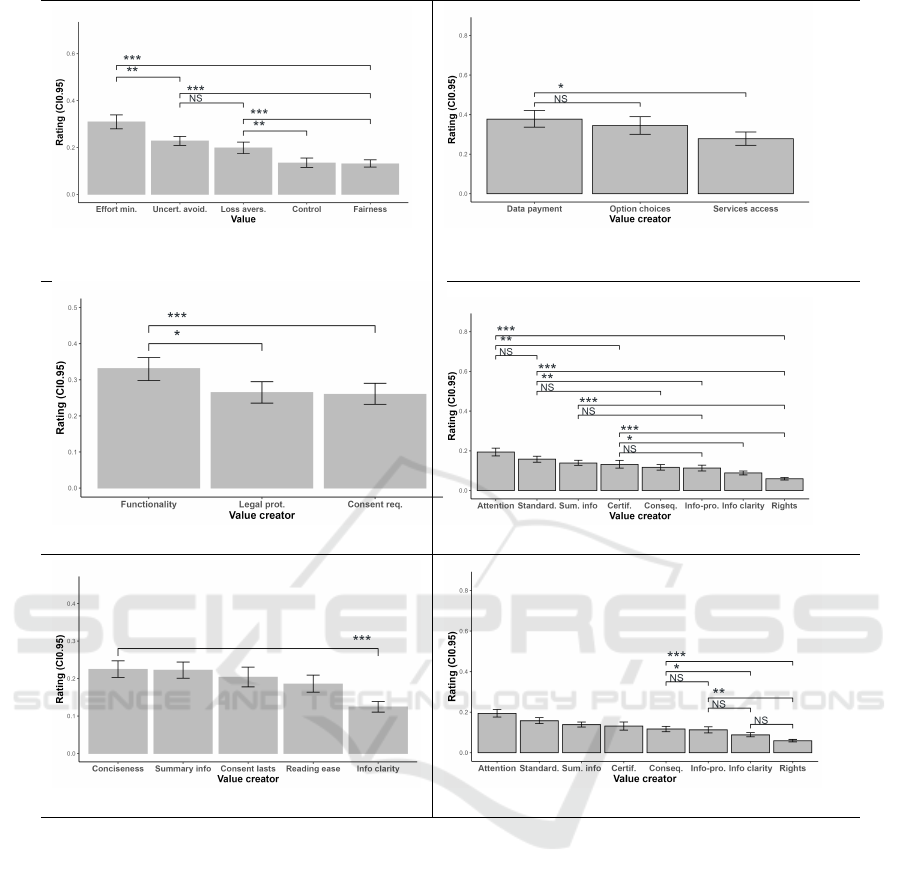

Weightings. The means with confidence inter-

vals (Diagrams in Figure 2 ) show substantial vari-

ability among the values for informed online consent

and among the value creators for each value (except

for loss aversion). t-tests showed no effect of em-

ployment status on any of the weightings. Two-way

mixed ANOVA, with Greenhouse-Geisser correction

for sphericity, showed no main effect of employment

status and no interaction effect of status with value or

value creator on any of the measures, for informed

online consent or any of the four values. Two-way

mixed ANCOVA showed that neither were ATI and

OPLIS significant covariates. Therefore, the results

of one-way repeated-measures ANOVA with value or

value creator as the independent variable, corrected

for sphericity, are reported here. The results for CR

< 0.10 are reported here (the results for CR < 0.20

[available on request] follow the same pattern). The

main effects of value (for informed online consent)

and value creator (for each of the values) are reported

here as well as pairwise comparisons.

For informed online consent, the effect of value

was significant, F (3.12, 227.75) = 33.67, p < 0.001,

pes = 0.32. Effort minimisation was the dominant

value (greater mean than that of the other values), fol-

lowed by uncertainty avoidance and loss aversion. For

the value of control, the effect of value creator was

significant, F (1.85, 105.62) = 3.74, p = 0.03, pes =

0.06. The mean for payment for data was greater than

that for access to services. For the value of fairness,

the effect of value creator was significant, F (1.97,

140.14) = 8.08, p < 0.001, pes = 0.10. Functional-

ity was the dominant value (greater mean than that of

the other value creators). For the value of uncertainty

avoidance, the effect of value creator was significant,

F (4.89, 246.89) = 20.20, p < 0.001, pes = 0.32. At-

tracting your attention was the most dominant value

creator (higher mean than that of the other value cre-

ators, except for Standardisation), followed by Stan-

dardisation, and summary information and certifica-

tion. For the value of effort minimisation, the effect

of value creator was significant, F (3.26, 205.53) =

10.29, p < 0.001, pes = 0.14. Information clarity had

the lowest weighting (mean smaller than that of the

other value creators); the other value creators were

not significantly different. For the value of loss aver-

sion, the effect of value creator was not significant, F

(1, 203) = 2.61, p = 0.11, pes = 0.01.

4 DISCUSSION & REFLECTION

The relative quantification of values and value cre-

ators shown in Figure 2 is instructive. In particular,

the results show that effort minimisation is most im-

portant. This justifies our proposal of reducing length

of policies so as to reduce effort. However, the sec-

ond most important one is uncertainty avoidance, so

it is important to ensure that in reducing length we

ensure that the information people want is easily ac-

cessed. We can use the value creators as a steer in

terms of what information people want to see in a con-

sent form.

The surprising finding is related to the relatively

low ranking of control. This is interesting because the

very consent form mechanism is based on the assump-

tion that users want to control their privacy, in other

words have control over who has their data and how

these are used (Human Rights Watch, 2018). The rel-

atively low ranking of control, accompanied by the

low ranking of consumer rights as a value creator,

by both unemployed and employed participants, calls

this assumption into question. This apparent indif-

ference might be due to the issues mentioned earlier,

namely the frequency with which users are presented

with these forms, and the effort that is required to pro-

cess them. It might be that they are making a perfectly

reasonable trade-off in order to be able to get anything

done at all.

The other surprising low-ranked value is fairness,

because we know that humans have a deep need to be

treated fairly (Folger et al., 1998; Folger and Cropan-

zano, 2001; Nicklin et al., 2011; Folger and Cropan-

zano, 2011; Ganegoda and Folger, 2015; Folger and

Shukla, 2019). Even so, our participants indicated

that this value did not mean as much to them as the

other values. It might be that people have come to ex-

pect to be treated unfairly in this domain, or that effort

minimisation and uncertainty avoidance are just that

much more important in this context.

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

138

Informed Consent Control

Fairness Uncertainty Avoidance 1/2

Effort Minimisation Uncertainty Avoidance 2/2

* p <0.05; ** p <0.01; *** p <0.001; NS: not significant.

Figure 2: Value Creator Weightings for Informed Online Consent Means with Confidence Intervals.

5 CONCLUSION & FUTURE

WORK

To address problems associated with online consent

from a user’s perspective, we suggest a value-driven

approach which can be used to remove information

(and shorten the policy) by providing information that

users value rather than all possible information in the

consent form. To apply this approach, we needed to

understand what users value. We decided to focus on

the values of unemployed users given the particular

challenges they face in protecting their privacy online.

The raison d’

ˆ

etre for this research was thus to in-

form a value-driven approach in reducing the length

of consent forms, with a specific focus on unem-

ployed users. We carried out two studies which, to-

gether, delivered a quantified hierarchy of values and

value creators. This will inform the next stage of our

study where we will carry out an empirical study to

compare user preference and comprehension of a tra-

ditional consent form versus a value-driven consent

form.

As future work, it would be very interesting and

important to explore the reasons behind these rank-

ings so that we understand users’ thought processes

when contemplating and dealing with online consent

forms.

A Value-Driven Approach to the Online Consent Conundrum: A Study with the Unemployed

139

REFERENCES

Beauchamp, T. L. (2011). Informed consent: its history,

meaning, and present challenges. Cambridge Quar-

terly of Healthcare Ethics, 20(4):515–523.

Chomanski, B. and Lauwaert, L. (2023). Online con-

sent: how much do we need to know? AI & SO-

CIETY, pages 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-

023-01790-2.

Dolan, J. G. (1989). Medical decision making using the ana-

lytic hierarchy process: choice of initial antimicrobial

therapy for acute pyelonephritis. Medical Decision

Making, 9(1):51–56.

Dolan, J. G. (2008). Shared decision-making - transferring

research into practice: The analytic hierarchy process

(ahp). Patient Education and Counseling, 73(3):418 –

425. 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.032.

Dolan, J. G., Isselhardt, B. J., and Cappuccio, J. D.

(1989). The analytic hierarchy process in medi-

cal decision making: a tutorial. Medical Deci-

sion Making, 9(1):40–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/

0272989X8900900108.

Edelsbrunner, P. A. (2022). A model and its fit lie in the eye

of the beholder: Long live the sum score. Frontiers

in Psychology, 13:986767. https://doi.org/10.3389/

fpsyg.2022.986767.

Folger, R. and Cropanzano, R. (2001). Fairness theory: Jus-

tice as accountability. In Greenberg, J. and Cropan-

zano, R., editors, Advances in Organizational Justice,

volume 1, pages 1–55. Stanford University Press.

Folger, R. and Cropanzano, R. (2011). Social hierarchies

and the evolution of moral emotions. In Schminke,

M., editor, Managerial Ethics, pages 225–252. Rout-

ledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203852460.

Folger, R. and Shukla, J. (2019). A fairness theory up-

date. In Lind, E. A., editor, Social Psychology and

Justice, pages 110–133. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.

4324/9780203852460.

Folger, R. G., Folger, R., and Cropanzano, R. (1998). Orga-

nizational Justice and Human Resource Management,

volume 7. Sage.

Franke, T., Attig, C., and Wessel, D. (2019). A Per-

sonal Resource for Technology Interaction: Devel-

opment and Validation of the Affinity for Technol-

ogy Interaction (ATI) Scale. International Journal

of Human-Computer Interaction, 35(6):456 – 467.

10.1080/10447318.2018.1456150.

Ganegoda, D. B. and Folger, R. (2015). Framing effects

in justice perceptions: Prospect theory and counter-

factuals. Organizational Behavior and Human Deci-

sion Processes, 126:27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

obhdp.2014.10.002.

Human Rights Watch (2018). The eu general data protec-

tion regulation. https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/06/

06/eu-general-data-protection-regulation.

Kilwinger, F. B. and van Dam, Y. K. (2021). Methodolog-

ical considerations on the means-end chain analysis

revisited. Psychology & Marketing, 38(9):1513–1524.

https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21521.

Masur, P. K., Teutsch, D., and Trepte, S. (2017).

Entwicklung und validierung der online-

privatheitskompetenzskala (OPLIS). Diagnostica.

McDonald, A. M. and Cranor, L. F. (2008). The cost of

reading privacy policies. Isjlp, 4:543.

Nicklin, J. M., Greenbaum, R., McNall, L. A., Folger, R.,

and Williams, K. J. (2011). The importance of con-

textual variables when judging fairness: An exam-

ination of counterfactual thoughts and fairness the-

ory. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision

Processes, 114(2):127–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

obhdp.2010.10.007.

Parfenova, D., Niftulaeva, A., and Carr, C. T. (2024).

Words, words, words: participants do not read con-

sent forms in communication research. Communica-

tion Research Reports, pages 1–11.

Seabright, P. (2010). The company of strangers. Princeton

University Press.

Solove, D. J. (2012). Introduction: Privacy self-

management and the consent dilemma. Harv. L. Rev.,

126:1880.

Trepte, S., Teutsch, D., Masur, P. K., Eicher, C., Fischer,

M., Hennh

¨

ofer, A., and Lind, F. (2015). Do peo-

ple know about privacy and data protection strate-

gies? Towards the “Online Privacy Literacy Scale”

(OPLIS). In Gutwirth, S., Leenes, R., and de Hert,

P., editors, Reforming European data protection law,

pages 333–365. Springer.

Van Schaik, P., Irons, A., and Renaud, K. (2024). Privacy in

uk police digital forensics investigations. In HICSS,

pages 1901–1910.

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

140