Preliminary Technical Test of Different Physiological

Modalities to Detect Workload in Humans in Microgravity

Judith Bütefür

1

and Elsa Andrea Kirchner

1,2 a

1

Institute of Medical Technology Systems, University of Duisburg-Essen, Duisburg, Germany

2

Robotics Innovation Center, German Research Center for Artificial Intelligence (DFKI GmbH), Bremen, Germany

Keywords: Workload, Multimodal, EEG, ET, ECG, RESP, Microgravity, Parabolic Flight, ZeroG.

Abstract: In this work we aim to investigate whether eye tracking, electrocardiogram and respiration are good measures

to detect workload (WL) of humans in microgravity. To this end, an auditory N-back study was performed

during a parabolic flight in microgravity and during a control condition in the lab under Earth gravity by 3

operators of the experiment. The data were analysed regarding their predictive nature to estimate WL. The

results show that none of the parameters are suitable for WL detection in humans due to the very short

microgravity phases (~22s) and due to scopolamine intake. Nevertheless, some parameters are potentially

suitable for longer stay in microgravity. In addition, the results of this study were compared with the results

of a previously published electroencephalogram (EEG) analysis on the same data set. This comparison shows

that EEG is a more promising predictor modality for WL. In future work, we will conduct another study to

extend the number of operators. Different conditions than short term parabolic flights and measurement with

longer duration are needed to investigate the stability of WL prediction.

1 INTRODUCTION

To be aware of the overall workload (WL) level of a

person during a given task is helpful in different

areas. It is an advantage to know the overall WL level

of a person to prevent mental disorders as, for

example, burnout due to permanent stress and

overload (Greif & Bertino, 2022). The tendency

towards mental disorders increased in the past (World

Health Organization, 2024) and this must be avoided

as much as possible. To protect people working in

safety-critical environments, they must be better

monitored in terms of WL. In space it is important to

know the WL level of each astronaut, since a higher

level of WL is related to a higher risk to make

mistakes (Morris & Leung, 2006). For astronauts it is

important not to make mistakes during complex tasks

outside the ISS, as this can quickly end fatally. During

space missions people experience microgravity, so

gravitational conditions are different from those on

Earth. As people are used to perform their tasks in

Earth gravity, microgravity will likely have an impact

on the overall WL since astronauts are not used to it

in general. The Multiple Resource Model by Wickens

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5370-7443

(2008) shows that many different dimensions have an

influence on the overall WL of a person. The model

shows that spatial activities and visual processing

have an influence on the WL, which can be

transferred to objects in microgravity that behave

significantly differently from those in Earth gravity.

As a result, the astronauts need more resources to

analyse how the objects behave, which implies a

higher WL. Because of all these aspects, the effect of

changing gravitational conditions on the WL is

important. To introduce different gravitational

conditions for short periods of time, especially

microgravity, without going in space, it is possible to

carry out parabolic flights. However, these flights are

very expensive and the time available in microgravity

is comparatively short. For this, an airplane (A310

Zero-G) based at Mérignac International Airport in

Bordeaux, France follows a given flight protocol,

which is shown in Figure 1. Each flight begins with a

test parabola after launch, followed by 30 parabolas

that can be used to conduct experiments. Each

parabola lasts about 70s, starting with about 20-25s

hyper-gravity (1.8G), followed by 21-22 seconds

microgravity (0G), which is highlighted in grey in

Bütefür, J. and Kirchner, E. A.

Preliminary Technical Test of Different Physiological Modalities to Detect Workload in Humans in Microgravity.

DOI: 10.5220/0013092600003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 1, pages 837-845

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

837

Figure 1, and ends up with again 20-25s hyper-gravity

(1.8G). Before the next parabola begins, there is a

break of 90s under Earth gravity (1G). After each set

of 5 parabolas there is a longer break of 5 or 8 minutes

after 15 parabolas. (Novespace, 2011).

Figure 1: Experimental design (Bütefür, Trampler, &

Kirchner, 2024).

The literature shows that WL can be determined

based on different physiological signals.

In this work we will investigate, if the prediction

of changes in WL in microgravity is possible using

the following modalities:

• Eye Tracking (ET),

• Electrocardiogram (ECG) and

• Respiration (RESP)

ET is a very common modality for WL estimation

in Earth gravity. ECG and RESP are very interesting

to compare for Earth gravity and microgravity, since

different gravity conditions have an impact to the

cardiovascular system of a person (Schlegel, et al.,

1998) as well.

The aim of this paper is to see, if measuring the

three mentioned modalities is possible in

microgravity during a parabolic flight and compare

the results to the results of electroencephalogram

(EEG) measurements recorded in the same study,

which are already analysed (Bütefür, Trampler, &

Kirchner, 2024). Therefore, the data from the

parabolic flight will be analysed in terms of WL and

compared to the analysed data from the control

condition in the lab. A comparison to the results from

the EEG analysis will also be done. It was already

shown in Bütefür et al. (2024) that it is possible to

analyse EEG data to determine WL in microgravity.

Therefore, the change in frequency bands was

analysed.

2 WORKLOAD DETECTION

BASED ON DIFFERENT

MODALITIES

This section provides information about the

modalities ET, ECG and RESP with respect to the

expected changes due to changing levels of WL.

In the following section the levels of WL are

divided into “lower” and “higher” WL. This always

means the distinction between the same task (auditory

N-back) with a lower and higher WL condition.

2.1 Eye Tracking

ET measures the eye movements during an

experiment with use of infrared light. For WL

detection in humans, it is a common modality, if the

experimental setup is designed carefully. If too many

eye movements are caused by the experimental setup,

the ET data can be distorted. Because it is not clear

whether the eye movements are caused by the change

of WL or the experimental setup. The same applies to

changing lightning conditions. Some of the parameters

that can be extracted from ET data to analyse WL are,

for example, the fixation duration, pupil dilation or the

blink frequency in a certain time window (Singh,

Ponzoni Carvalho Chanel, & Roy, 2021; Volden,

Alwis, de Viveka, & Fostervold, 2018).

Some groups reported an increase of the pupil

dilation if the WL is higher in comparison to lower

WL conditions (Grimmer, Simon, & Ehlers, 2021;

Singh, Ponzoni Carvalho Chanel, & Roy, 2021;

Volden, Alwis, de Viveka, & Fostervold, 2018).

Other changes of parameters in higher WL condi-

tions are a higher blink frequency (more eye blinks in

a certain amount of time) and an increase of the peak

blink duration as well as the number of eye blinks

(Volden, Alwis, de Viveka, & Fostervold, 2018).

2.2 Electrocardiogram

The ECG is a modality that is often measured in the

context of physical demanding tasks, as these have a

strong influence on the cardiovascular system.

However, there are also some parameters that change

when the subject performs cognitively demanding

tasks.

Volden et al. (2018) reported a significant higher

ratio of low frequency (LF) parts to high frequency

(HF) parts of the heart rate (HR) for higher WL in

comparison to lower WL conditions.

Singh et al. (2021) reported a significant increase

in the HR and a significant decrease in the heart rate

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

838

variability (HRV). Ding et al. (2020) reported an

almost significant increase in the HR for high WL in

comparison to low WL, whereas there was no

significant change in HR between low and medium

WL level.

2.3 Respiration

RESP is also a modality which is often used in the

context of physical demanding tasks as it changes

significantly, in this case, as does the ECG. But there

is also one parameter of respiration reported, that

changes due to changing cognitive WL. Ding et al.

(2020) reported a significant lower respiration rate

(RR) for lower WL in comparison to higher WL.

3 METHODS

In this section the dataset will be presented in general

as well as the experimental setup and procedure. A

detailed description can be found in the main study of

Bütefür et al. (2024). The section also contains

information about the data recording of ET, ECG and

RESP, as well as pre-processing and the data analysis.

3.1 Dataset

The dataset consists of two studies. The first study

took place during a parabolic flight campaign (flight

environment) organized by DLR Space Agency and

Novespace. The experimental setup during the flight

is shown in Figure 2. The second study was used as a

control condition and took place in the laboratories of

the University of Duisburg-Essen (lab environment).

The experimental setup in the lab is similar to the

setup in flight (cf. Figure 2), except the operator is

sitting on a chair and not on the ground and the

response button was a key on the keyboard in front of

the operator.

3.2 Participants

EEG, ECG, RESP and ET data for both studies were

measured from three healthy, native German speaking

team members who were operators of the experiment

(1 male, average age = 43 ± 12,7). The study was a

purely technical test, which is why no ethic statement

was required under French law. For the parabolic flight

all operators took scopolamine (a medication to

prevent motion sickness) on a voluntary basis.

Operator AE41D had to be excluded for the

analysis, as the measurement took place on two days

due to technical problems with the aircraft during the

first flight and was therefore not comparable to the

analysis of the other operators who did the whole

study in one session.

Figure 2: Experimental setup (adapted from (Bütefür,

Trampler, & Kirchner, 2024)).

3.3 Experimental Setting

The operators had to perform an auditory N-back task

during the microgravity phases in the plane (see Figure

1 depicting microgravity phases and experimental

design). The operator must listen to numbers (0, 3, 4,

7, and 9 spoken in German) presented as stimuli via

headphones. During the first 15 parabolas

(15*22sec=5.5min) the operators had to perform an

N=1 or N=2 task, which corresponds to low WL

condition. During the second half of the flight

(parabolas 16-30) operators had to perform an N=3

task to increase the difficulty of the task and

corresponds to high WL condition. The relation of

targets to standards was 1:6 for 135 stimuli in total

under each condition. The stimulus interval was 600ms

and the inter-stimulus interval 1800ms. Each run was

followed by a ~90s break. Each set consisted of 5 runs

followed by a longer break of 5 or 8 minutes, where the

operator had to fill out the NASA-TLX questionnaire.

The operators had to perform 3 sets for each condition.

Each set consists of 5 runs (parabolas).

The flight procedure was replicated for the control

conditions in the lab, but the breaks were shortened

from 90 seconds to 20 seconds and from 5 or 8

minutes to 90 seconds.

3.4 Data Recording and Pre-Processing

In the following paragraphs the data recording of the

different modalities is described as well as the pre-

processing.

ECG and RESP data were recorded synchronously

to EEG data with the same system. Therefore, each

Preliminary Technical Test of Different Physiological Modalities to Detect Workload in Humans in Microgravity

839

operator was prepared with the ANT eego mini

(https://www.ant-neuro.com/products/ eego_24),

which measured ECG and RESP with a sampling

frequency of 500 Hz. ECG was measured with 3

channel lead and RESP with a respiration belt. All

operators were prepared with a 24-channel dry

electrode headset as well. EEG data recording is

described more detailed in Bütefür et al. (2024).

During the experiment the operator was sitting in front

of the Tobii Pro Fusion Eye Tracker

(https://www.tobii.com/products/eye-trackers/screen -

based/tobii-pro-fusion) with a sampling frequency of

250 Hz during the parabolic flight and 120 Hz in the

lab and an accuracy of 0.3°. Data recording took place

using the Tobii Pro SDK (Tobii AB, 2024). During the

parabolic flight a synchronized inertial measurement

unit (IMU) measured the acceleration data.

Pre-processing for ECG and RESP data was done

with the python-library MNE. A bandpass filter

between 0.1 and 45 Hz was applied. Microgravity

phases during the parabolic flight were detected using

an IMU. This was used to mark the microgravity

phases within ECG, RESP, and ET data for evaluation.

3.5 ET Analysis

For ET analysis the data were segmented into single

runs (1 run = 1 parabola). The analysis was done in

python based on the eye position data recorded from

the eye tracker. The validity of the ET data was

checked before the analysis could start. The validity

was calculated based on the detection percentage of

pupil images for each eye during microgravity

phases.

The number of blinks, blink frequency and

maximum blink duration was also calculated from the

validity parameters, as no eye image could

recognized when blinking. A blink was recognized if

the no eye images could be detected for the left and

the right eye for 100-500ms and anything above

500ms was considered as drowsiness (Aksu, Cakit, &

Dagdeviren, 2024). The blink frequency was

calculated using the time between the first and last

blink and the number of blinks. The pupil diameter

was also analysed. This parameter is calculated by the

Tobii Pro SDK (Tobii AB, 2024) during

measurement and can be extracted and analysed from

the data for each eye individually. To analyse the

parameters the median of each run was calculated for

each parameter individually with respect to the

different WL conditions. Also, the median over all

runs for lower and higher WL condition was

calculated for each operator in both environments.

3.6 ECG and RESP Analysis

For ECG and RESP analysis the NeuroKit2 toolbox

(Makowski, et al., 2021) was used.

To analyze the ECG data, the N-back task data

were segmented into epochs of 15s with 10s overlap.

Afterwards, HR was interpolated between R-Peaks

and HRV was calculated using the standard deviation

of RR intervals. LF/HF ratio was also calculated. All

calculations were done using the NeuroKit2 toolbox

(Makowski, et al., 2021).

The median of each parameter and run for lower

WL condition was calculated as well as the median of

each parameter and run for higher WL condition.

Also, the median over all runs for lower and higher

WL condition was calculated for each operator in

both environments.

To analyze the RESP data, the N-back task data

were segmented into epochs of 20s without any

overlap. The inhalation onsets were calculated using

the NeuroKit2 toolbox (Makowski, et al., 2021). The

RR was calculated and the median for each set was

built. An outlier removal was performed, whereby the

90

th

percentile of data was used. Also, the median

over all runs was built for the lower as well as the

higher WL condition.

4 RESULTS

In the following section the results for all modalities

and the different parameters are presented.

4.1 ET Results

The ET data were evaluated with respect to the

validity, number of blinks, blink frequency and the

maximum blink duration.

In Table 1 the percentage of validity is shown for

each operator and for lower and higher WL condition

in both environments (flight and lab).

Table 1: Validity of left and right eye for each operator and

condition in both environments.

Sub

j

ect AC07D BU87D

Validity (%) Left Right Left Right

Lab

Low

WL

81.88 82.44 97.06 96.62

High

WL

82.15 83.94 96.60 96.26

Flight

Low

WL

74.73 71.35 84.46 79.82

High

WL

57.96 52.71 76.00 71.00

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

840

The results show an overall validity over 50% for

each WL condition in both environments. The highest

difference between left and right pupil validity is

5.25% for BU87D in flight environment. The smallest

difference is 0.34% for BU87D in lab environment.

The average validity in lab environment is

89.62% ± 7.53%. In flight environment the average

validity is 71.00% ± 10.71%.

The average validity for both eyes for Operator

AC07D is 73.39% ± 12.03% and for BU87D

87.23% ± 10.73%.

For lower WL condition the average validity is

83.55% ± 9.25% and for higher WL condition

77.08% ± 16.12%.

4.1.1 Eye Blinks

In this section the results of all parameters regarding

eye blinks will pe presented. In Figure 4A the

boxplots for the number of eye blinks for all runs and

WL conditions in both environments are shown,

while Figure 4B presents the blink frequency for all

conditions and Figure 4C the maximum blink

duration. The median is marked with a red line. The

absolute number of eye blinks increased for higher

WL condition for each operator in both environments

except for BU87D in the lab environment.

On the contrary the blink frequency decreases for

higher WL condition for each operator in both

condition except for BU87D in the lab environment.

These results are inverted to the number of eye blinks.

Furthermore, for BU87D, the blink frequency in lab

environment for higher WL condition could only be

calculated for one run, as the number of blinks was less

than 2 in all other runs. For this one run the frequency

was higher for higher WL condition in comparison to

lower WL condition. For lower WL condition the

frequency could be calculated for 2 runs.

The pattern of the maximum peak blink duration

is the same as for the number of eye blinks, which

means that the maximum peak blink duration

decreases for higher WL condition in comparison to

lower WL condition for both operators in each

condition except for Operator BU87D in lab

environment, there it remains the same.

4.1.2 Pupil Diameter

The boxplots of the median of pupil diameter per run

for the right eye are illustrated in Figure 4D represent-

tative for both eyes. The median pupil diameter

decreases for higher WL condition in comparison to

lower WL condition for both operators in the flight

environment and increase from lower to higher WL

condition for both operators in the lab environment.

For the right eye the changes were similar.

A)

B)

C)

D)

Figure 3: Eye blink parameters for both operators under

each condition; A) Number of eye blinks; B) Blink

frequency; C) Maximum blink duration.

Preliminary Technical Test of Different Physiological Modalities to Detect Workload in Humans in Microgravity

841

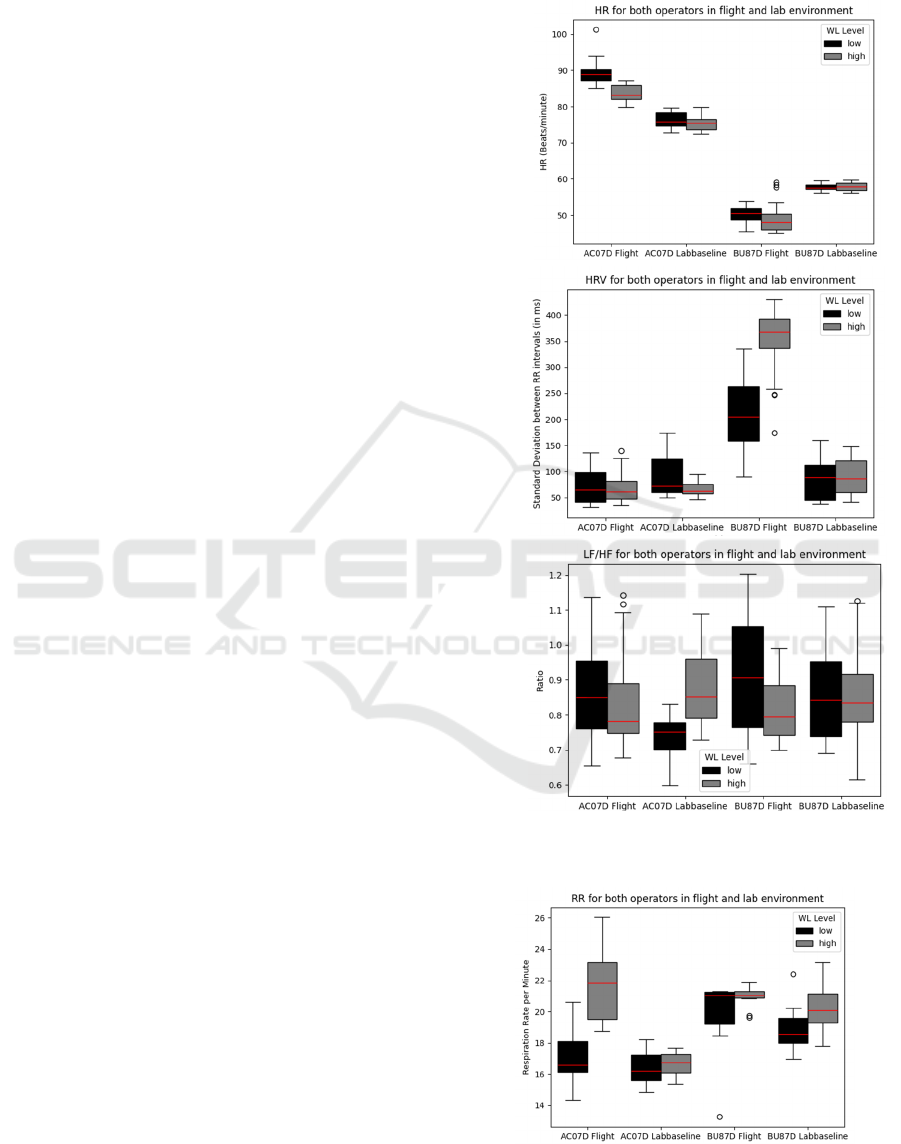

4.2 ECG Results

In the following section the results of the ECG

analysis will be presented.

Figure 4 shows the results for both operators in

each environment. In Figure 4A the boxplots of the

median HR for each run and operator under lower and

higher WL condition is shown. The HR decreases for

both operators in the flight environment and for

AC07D in the lab environment for higher WL

condition in comparison to lower WL condition. For

Operator BU87D in the lab environment the median

HR decreases for higher WL condition in comparison

to lower WL condition (cf. Fig. 4A).

Figure 5B shows the boxplots of the median HRV

of each run for lower and higher WL condition for

each operator in both environments. The median

HRV over all runs decreases for higher WL condition

in comparison to lower WL condition for both

operators in lab environment and for AC07D in flight

environment. For BU87D in flight environment the

median HRV over all sets increased for higher WL

condition in comparison to lower WL condition.

The boxplots of the median of the LF/HF ratio for

each run and operator under lower and higher WL

condition are depicted in Figure 4C. It decreases for

both operators in the flight environment and for

BU87D in the lab environment for higher WL

condition in comparison to lower WL condition. For

Operator AC07D in the lab environment the median

LF/HF ratio decreases for the higher WL condition in

comparison to the lower WL condition.

4.3 RESP Results

In the following section the results of the RESP

analysis will be presented.

The boxplots of the median RR for each run and

operator in both environments are illustrated in Figure

5. The median RR increases for both operators in both

environments for higher in comparison to lower WL

condition.

5 DISCUSSIONS

The main objective of this paper was to investigate, if

measuring the modalities ET, ECG and RESP is

technically possible in microgravity during a parabolic

flight in a quality that it allows to predict WL levels.

Therefore, the data from the parabolic flight were

analysed in terms of WL and compared to the analysed

data from the control condition in the lab. As a subgoal

the results for ET, ECG and RESP will be compared

with the results from the EEG analysis, which are

already published in Bütefür et al. (2024).

A)

B)

C)

Figure 4: ECG parameter for both operators in each

environment; A) HR; B) HRV; C) LF/HF ratio.

Figure 5: Median RR for each run and operator under both

conditions.

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

842

The results of the validity of the ET in Table 1

show that the validity of the data measured in lab

environment was higher with an average validity of

89.62% ± 7.53% than in flight environment with

71.00% ± 10.71%. This is due to the fact, that during

microgravity phases in flight environment the

operator starts floating around. With the given

experimental design, it was not possible to fixate the

operator fully on the plane ground, so the operator

floated out of the region of measurement from the ET.

In lab environment, however, it was not the case since

the operator was sitting on a chair in Earth gravity.

The validity was also not expected to have 100%

because for each eye blink pupil images cannot be

detected. If the validity is compared to the number of

eye blinks (Fig. 4A), the validity is lower for

conditions with a higher number of eye blinks and is

also proportional related to the maximum blink

duration (Fig. 4C), which was expected.

The analysis of the number of eye blinks (cf. Sec.

4.1.1) shows an increase of the number of eye blinks

with an increase of WL condition in both

environments except for BU87D in lab environment

(cf. Fig. 4A). An increase of the number of eye blinks

for increasing WL condition was also expected from

literature (Volden, Alwis, de Viveka, & Fostervold,

2018) and is supported in this study by the higher

validity percentage for lower WL condition (see Tab.

1). However, these results must be viewed with

caution, as the duration of each run was only 22s and

the standard number of blinks per minute are between

2 and 50 (Monster, Chan, & O'Connor, 1978). This

means that if the operator blinks less in general, the

number of blinks over a short period of time is not

representative. As a conclusion, it seems like this

parameter is technically measurable in microgravity,

but within this experimental setup it is very limited

due to the short period of time where it is measured.

The blink frequency was analysed as well (cf. Sec.

4.1.1) and results were contrary to the results of the

number of eye blinks. From literature it was expected

that the blink frequency is increasing with increasing

WL condition (Volden, Alwis, de Viveka, &

Fostervold, 2018), but Figure 4B shows a decrease in

three out of four cases. For the fourth case, BU87D in

lab environment, the median blink frequency

increases, but in most of the runs there were less than

two eye blinks, so it was not possible to calculate the

frequency of eye blinks within these runs, which

means that this result is not representative. As already

discussed before, 22s for each run within this

experiment is not sufficient for analysing changes in

the WL levels of the operators based on ET

parameters. Furthermore, the calculation of the blink

frequency is another limiting factor. Due to long

phases of closed eyes at the beginning of single runs,

as well as inaccuracies of measures due to the onset

of hyper-gravity at the end of each run, the blink

frequency was only calculated in the time between the

first and the last recognised blink. This leads to a low

robustness of the calculation for a small sample size,

which becomes clear due to the large variation of the

calculated frequencies, e.g., for Operator BU87D in

the lab environment (cf. Fig. 4B). Operator AC07D

also shows many outliers in the flight environment,

which indicate this. It seems like this parameter is not

suitable for experimental setups with short-term

measurements independent of the prevailing

gravitational conditions.

The results of the maximum blink duration are

shown in Figure 4C, which illustrates an increase of

the overall median of the maximum blink duration for

higher WL condition in comparison to lower WL

condition in all environments except for BU87D in

lab environment. For BU87D in lab environment the

maximum blink duration decreases. The results are

inhomogeneous which could be due to the small

sample size of only two operators within this study.

Volden et al. (2018) had 21 subjects and removed

four outliers to obtain normal distribution. Also, the

definition of the maximum length of a blink varies. In

this work a blink was defined between 100ms and

500ms (cf. Sec. 3.4) regarding the work of Aksu et al.

(2024), because a typical blink lasts between

100ms – 300ms and blinks about 500ms are

considered as drowsiness (Johns, 2003). Volden et al.

(2018) did not define time limits for eye blinks and

had a mean maximum blink duration of

973.21ms ± 637.66ms, which would be drowsiness

instead of eye blinks regarding the definition within

our work. Therefore, this parameter needs to be more

investigated in Earth gravity as well as in

microgravity with longer periods of measurements

and the given limitations.

The last parameter analysed for ET data was the

pupil diameter for both eyes (Sec. 4.1.2). Figure 4D

depicts that the median pupil diameter over all runs of

the right eye decreases for higher WL condition in

comparison to lower WL condition for both operators

in both environments. For flight environment the

decrease seems higher and could be explained by the

use of scopolamine since ophthalmic adverse effects

are expected with that (Merck & Co., Inc., 2024). The

pupil diameter seems also not to be a suitable

parameter in microgravity with scopolamine intake

and also need further tests for Earth gravity.

The HR was analysed from ECG data with respect

to the WL conditions (Fig. 5A). The HR decreased for

Preliminary Technical Test of Different Physiological Modalities to Detect Workload in Humans in Microgravity

843

both operators for higher WL condition in

comparison to lower WL condition, which was not

expected from literature (Ding, Cao, Duffy, Wang, &

Thang, 2020; Singh, Ponzoni Carvalho Chanel, &

Roy, 2021). Due to these results, it is not possible to

decide if the HR is a suitable parameter for WL

detection in microgravity since with the sample size

of two operators it was not even possible to reproduce

the results from Ding et al. (2020) in Earth gravity.

For the HRV the results are very similar to those

for HR. Figure 5B shows that only for Operator

AC07D in the lab environment the HRV slightly

decreases for higher WL condition in comparison to

lower WL condition as it was expected from literature

(Singh, Ponzoni Carvalho Chanel, & Roy, 2021). For

Operator BU87D in the flight environment the HRV

increased for higher in comparison to lower WL

condition, which was not expected. Figure 5B also

illustrates that the median HRV over all runs for

Operator BU87D in flight environment is

unexpectedly high. Therefore, the signal was visually

checked and the calculation was correct. The

unexpected high HRV for BU87D in flight

environment could be affected by use of scopolamine

since one of the adverse reactions are also cardiac

arrhythmias (Merck & Co., Inc., 2024). Due to this

fact, HRV seems not to be suitable for WL detection

in microgravity by use of scopolamine.

The results of the LF/HF ratio analysis, which are

presented in Figure 5C, show also similar results to

HR and HRV. Only for Operator AC07D in the lab

environment the LF/HF ratio is increasing from lower

to higher WL as expected in literature (Volden,

Alwis, de Viveka, & Fostervold, 2018). As already

mentioned before, because of scopolamine intake and

adverse reactions the LF/HF ratio also seems not to

be a suitable parameter for WL detection under

scopolamine.

Figure 5 shows that the RR increases for both

operators in both environments for higher in

comparison to lower WL condition as expected in

literature (Ding, Cao, Duffy, Wang, & Thang, 2020).

But only for Operator AC07D in flight environment

the increase seems relevant, as for the other

conditions the overall median remains almost the

same. Data from a longer period of time is required to

analyse the RR because the frequency of RESP is low

in comparison to the length of one run. It seems like

that RR is not a suitable parameter for short term

measurement in microgravity. Nevertheless, it should

be analysed for longer measurement durations.

After analysing all mentioned parameters, it can

be summarised that none of the parameters would be

suitable for WL detection in humans in the very short

microgravity phases (~22s) and using scopolamine

for the described experimental setting. For the HR

and RR more data would be needed to reproduce the

results from literature also in Earth gravity.

As a subgoal we wanted to compare the results of

this work to the results of the EEG analysis. In the

work of Bütefür et al. (2024) the EEG data of the

study were analysed in the frequency domain. To this

end, the single frequency bands were compared

regarding increasing or decreasing power spectral

density for changing WL conditions. The conclusion

of the analysis was that dry electrode headsets could

be a promising alternative for the detection of WL in

microgravity if the headset fits the subject.

In this work we could not show a suitable

parameter for analysing WL for the mentioned

experimental setup.

In summary, comparing the results of this work

with former results, EEG frequency bands for the

detection of WL in microgravity with scopolamine

intake and short-term measurements is the most

promising approach, as it brings the only reliable

results.

For future work another experimental setting

should be set up where longer measuring durations

are possible so that the HR and RR, as well as the ET

parameter could be analysed more detailed, and the

state of the art could be reproduced to verify the

parameters in microgravity. The measurement period

during parabolic flights is pretty fixed so that another

possibility to introduce microgravity needs to be

found. Also, more operators should be included to

minimize the effect of individuality in humans and a

statistical analysis could be performed. Scopolamine

intake should be avoided as well.

6 CONCLUSIONS

In this study we investigated whether the use of the

modalities ET, ECG and RESP could be a viable way

to detect WL of humans in microgravity. Our results

suggests that under scopolamine and for short-term

measurements only EEG data brings results

comparable to the control condition in Earth gravity.

Therefore, we would suggest using EEG

measurements for WL detection as they bring the

most stable results as shown in an earlier published

work (Bütefür, Trampler, & Kirchner, 2024). As a

next step a larger sample size of operators is needed.

Also, the experimental setup needs to be adapted to

get data from a longer period to investigate ET, ECG

and RESP data more detailed.

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

844

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to express our gratitude to all the

operators of the study, as well as Marc Tabie and

Mathias Trampler, who setup the experiment. We

would also like to thank DLR Space Agency for

funding our experiments during the 42

nd

parabolic

flight campaign in Bordeaux, France. The work was

supported by the German Federal Ministry for

Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK)

under the grant number FKZ 50RP2270A (UDE) and

FKZ 50RP2270B (DFKI) in the project GraviMoKo.

REFERENCES

Aksu, S., Cakit, E., & Dagdeviren, M. (2024). Mental

Workload Assessment Using Machine Learning

Techniques Based on EEG and Eye Tracking Data.

Applied Sciences, pp. 2282, doi: https://doi.org/10.33

90/app14062282.

Bütefür, J., Trampler, M., & Kirchner, E. (2024,

Decemeber). Technical Test of a Dry Electrode Headset

for EEG Measurement in Microgravity. In M. Guarino,

Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies.

BIOSTEC 2024. Communications in Computer and

Information Science. Springer (to be published).

Ding, Y., Cao, Y., Duffy, V. G., Wang, Y., & Thang, X.

(2020). Measurement and identification of mental

workload during simulated computer tasks with

multimodal methods ans machine learning. Ergonomics

63 (7), pp. 896-908, doi: 10.1080/00140139.2020.17

59699.

Greif, S., & Bertino, M. (2022). Burnout: Characteristics

and Prevention in Coaching. In S. Greif, H. Möller, W.

Scholl, J. Passmore, & F. Müller, International

Handbook of Evidence-Based Coaching. Springer,

Cham. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-1938-5_9.

Grimmer, J., Simon, L., & Ehlers, J. (2021). The Cognitive

Eye: Indexing Oculomotor Functions for Mental

Workload Assessment in Cognition-Aware Systems.

Extended Abstracts of the 2021 CHI Conference on

Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 1-6.

Johns, M. (2003). The amplitude velocity ratio of blinks: A

new method for monitoring drowsiness. Sleep .

Makowski, D., Pham, T., Lau, Z., Brammer JC, Lespinasse

, F., Pham, H., . . . Chen, S. (2021). Neurokit2: A Python

toolbox for neurophysiological signal processing.

Behavior Research Methods, 53(4), pp. 1689-1696,

https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-020-01516-y.

Merck & Co., Inc. (2024). Merck Manual Professional

Version. Retrieved from https://www.merckmanuals.

com/professional/injuries-poisoning/motion-sickness/

motion-sickness?query=scopolamine#Diagnosis_v111

5169

Monster, A., Chan, H., & O'Connor, D. (1978). Long-term

trends in human eye blink rate. Biotelemetry and

Patient Monitoring, 5(4), pp. 206-222, PMID: 754827.

Morris, C. H., & Leung, Y. K. (2006). Pilot mental

workload: how well do pilots really perform?

Ergonomics 49 (15), pp. 1581-1596, doi: 10.1080/0014

01306008579787.

Novespace. (2011). 42nd DLR parabolic flight campaign

(VP179) - Practical and technical information.

Schlegel, T. T., Benavides, E. W., Barker, D. C., Brown, T.

E., Harm, D. L., DeSilva, S. J., & Low, P. A. (1998).

Cardiovascular and Valsalva responses during

parabolic flight. Journal of applied physiology, pp.

1957-1965, doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.5.1957.

Singh, G., Ponzoni Carvalho Chanel, C., & Roy, R. N.

(2021). Mental Workload Estimation Based on

Physiological Features for Pilot-UAV Teaming

Applications. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, pp.

22-28, doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2021.692878.

Tobii AB. (2024). Tobii Pro Toolkit tobii_research V2.0.

Retrieved from http://www.tobii.com/

Volden, F., Alwis, E., de Viveka, & Fostervold, K.-I.

(2018). Human Gaze-Parameters as an Indicator of

Mental Workload. Proceedings of the 20th Congress of

the International Ergonomics Association (IEA 2018).

Volume X: Auditory and Vocal Ergonomics, Visual

Erfonomics, Psychophysiology in Ergonomics,

Ergonomics in Advanced Imaging, pp. 209-215.

Wickens, C. D. (2008). Multiple resources and mental

workload.

Human Factors 50 (3), pp. 449-455, doi:

10.1518/001872008X288394.

World Health Organization. (2024, September 26). Mental

disorders. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-

room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders

Preliminary Technical Test of Different Physiological Modalities to Detect Workload in Humans in Microgravity

845