Qualitative In-Depth Analysis of GDPR Data Subject Access Requests

and Responses from Major Online Services

Daniela P

¨

ohn

1 a

and Nils Gruschka

2 b

1

University of the Bundeswehr Munich, Research Institute CODE, Munich, Germany

2

Department of Informatics, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

fi

Keywords:

GDPR, Data Protection, Data Subject Access Request.

Abstract:

The European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) grants European users the right to access their

data processed and stored by organizations. Although the GDPR contains requirements for data processing

organizations (e. g., understandable data provided within a month), it leaves much flexibility. In-depth research

on how online services handle data subject access request is sparse. Specifically, it is unclear whether online

services comply with the individual GDPR requirements, if the privacy policies and the data subject access

responses are coherent, and how the responses change over time. To answer these questions, we perform a

qualitative structured review of the processes and data exports of significant online services to (1) analyze the

data received in 2023 in detail, (2) compare the data exports with the privacy policies, and (3) compare the

data exports from November 2018 and November 2023. The study concludes that the quality of data subject

access responses varies among the analyzed services, and none fulfills all requirements completely.

1 INTRODUCTION

The modern world has become data-centric and dom-

inated by large enterprises that provide digital ser-

vices and collect large amounts of personal data. Fol-

lowing this, data has become a commodity exploited

and traded for commercial advantage, giving behav-

ioral insights for advertisements. To re-balance the

power over personal data, the European Union’s (EU)

General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (Euro-

pean Parliament, 2016) came into force on May 25,

2018. Among others, the GDPR grants individuals

(i. e., data subjects) rights to access their data and ex-

plain its usage in an electronic and understandable

form. Since then, similar regulations, such as the

California Consumer Privacy Act, have been intro-

duced worldwide. Research has mainly concentrated

on other GDPR-related topics, such as cookie ban-

ners and their effects on ad networks. Research on

data subject access request (DSAReq; short: request)

and data subject access response (DSARes; short: re-

sponse) is still rare. However, research concerning

data subject access with actual account data may pro-

vide insights into their compliance with the GDPR,

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6373-3637

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7360-8314

among other things. Hence, a qualitative in-depth

analysis of leading online services is essential.

Therefore, we initiated requests at Amazon,

Google, Facebook, Microsoft, LinkedIn, Apple, and

WhatsApp as the leading online services and retrieved

and analyzed the responses. This paper makes the fol-

lowing contributions: a qualitative analysis of the data

request process of leading online services in detail; a

matching of the responses with the corresponding pri-

vacy policies; a comparison of the responses from the

beginning of the GDPR and today. With these con-

tributions, we are addressing the following research

questions: Do the selected online services comply

with the GDPR concerning DSAReq and DSARes?

To what extent do the privacy policies match the data

responses? How do the responses from November

2018 and 2023 differ for the selected online services?

We summarize the background in Section 2 and

contrast the related work with our approach. In Sec-

tion 3, we outline our qualitative method. Section 4

comprises the study of the DSAReq workflows, the

DSARes, a comparison of 2018 and 2023, and an

evaluation of the privacy policies. Based on the re-

sults, we discuss our findings (see Section 5) and con-

clude the paper.

Pöhn, D. and Gruschka, N.

Qualitative In-Depth Analysis of GDPR Data Subject Access Requests and Responses from Major Online Services.

DOI: 10.5220/0013093000003899

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2025) - Volume 1, pages 149-156

ISBN: 978-989-758-735-1; ISSN: 2184-4356

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

149

2 RELATED WORK

The GDPR is the primary legal framework for data

protection within the European Union, including Nor-

way, Iceland, and Liechtenstein. The regulation de-

fines, among other things, fundamental principles and

definitions, obligations for organizations that process

personal data (“data controllers”), and rights of indi-

viduals whose data is processed (“data subjects”).

The main research topics in the area of GDPR

are tracking, cookies, and consent, dark patterns, and

compliance and enforcement. Fewer approaches ad-

dress the topic of DSAReq and DSARes. (Bowyer

et al., 2022) conducted a user study with ten par-

ticipants, in which each participant filed four to

five data access requests. The authors notice non-

compliance and low-quality responses. Similarly,

(Alizadeh et al., 2020) present a user study with 13

households who request DSARes from their loyalty

program providers. The authors conclude that the re-

sponses should deliver detailed information to prevent

mistrust. DSARes donations by users can be applied

in research (Boeschoten et al., 2021a; Boeschoten

et al., 2022; Boeschoten et al., 2021b; van Driel et al.,

2022). However, the data has to be cleaned from pri-

vate data. (Leschke et al., 2024) introduce a method

to create synthetic DSAR datasets, whereas (Peters

et al., 2023) outline the different variants of DSAReqs

at Instagram. In contrast, (P

¨

ohn et al., 2023) analyze

DSARes concerning conformity, finding differences

in the type of service and request method. (Leschke

et al., 2023) automate performing DSAReqs.

Based on the related work, only a few authors fo-

cus on data subject access requests and responses. A

qualitative in-depth analysis of actively used accounts

related to Art. 5 GDPR is missing. To notice changes

in the DSARes between years and users, comparing

the responses from several years and users could help

shed light on the practices of online services.

3 METHOD

We select the big five tech companies for our anal-

ysis: Google, Amazon, Apple, Meta (i. e., Facebook

and WhatsApp), and Microsoft. They are leading in e-

commerce, consumer electronics, online advertising,

online searches, and social media. Consequently, we

assume that they potentially collect a large amount of

data. We also select (LinkedIn, 2024) as a business-

focused social media platform with over 850 million

registered members from over 200 countries. We

utilize two actively used accounts for each service.

The accounts were created and used primarily in Eu-

rope. User A (female) is privacy-concerned with non-

standard operating systems, script blockers, and sim-

ilar, but shares some work-related data and regularly

buys items at Amazon. User B (male) uses standard

devices and no additional measures. They have used

their accounts for several years, as shown in Table 1.

We expect realistic results using these inartificial and

long-lived accounts and can analyze minimization,

retention time, and other requirements. Both users

consented to the analysis. As the DSARes contain

personal identifiable information, the users analyzed

their own data. This procedure is in line with the

ethical boards of the universities. To document the

Table 1: Account creation year for both main users.

Online service User A User B

Amazon 2006 2008

Apple 2007 2015

Facebook 2007 2009

Google 2009 2012

LinkedIn 2012 2009

WhatsApp 2013 2015

DSAReqs, we establish a template based on the re-

sults published by (P

¨

ohn et al., 2023; Leschke et al.,

2024). Next, the data is evaluated. We chose a man-

ual step-by-step process since automatic tools do not

provide the required detail.

4 RESULTS

In the following, we present the results per online ser-

vice. The summarized results are presented in Ta-

bles 3 and 4 in the Appendix. A comparison between

these online services is being made in Section 5.

4.1 Amazon

The user receives a DSARes with at least 47 folders,

including those for account settings, advertisements,

Alexa, app store, Audible, devices, digital content,

Prime Video, Kindle, notifications, payments, and

retail. One DSARes had 212 folders and 15,906 files.

Receiving an overview of the data might be difficult

without a primary HyperText Markup Language

(HTML) page. We found old email addresses in

several files that the users had changed. At several

locations, such as Amazon-Music or retail (i. e.,

their web store), searches requests (incl. search

terms and timestamps) are stored for the whole

lifetime of the account. The amount of data generally

is high, including old data from 2012 to 2015.

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

150

However, the data is, at least in parts, incomplete.

In the second step, we highlight specific files and

folders. The Alexa folder includes audio files and

transcriptions, though the user did not use Alexa but

an early version of a FireTV. The Smart Home folder

contains Alexa voice-enabled devices, including all

smartphones. Devices.Registration contains

all devices – multiple times, partly with the wrong

status. Digital.Content.Whispersync lists all

actions and states while reading, such as marked

text, started and stopped reading, reading speed, and

comments. Digital.PrimeVideo.LocationData

consists of various locations the users have been

to. One user with infrequent app usage could find

around 20 entries per day. This implies that Amazon

apps may collect data during non-usage phases.

OutboundNotification.AmazonApplicationUp

dateHistory shows all updates of Amazon

apps since 2020, with active debugging status.

Retail.AuthenticationTokens includes authen-

tication records with several old sessions that seem

to be still active. The shopping profile is some-

what amusing for both users (notice that User B is

male), as the shopping profile contains ‘female’ and

‘shoes’. Amazon’s privacy policy provides detailed

information about the data it collects, processes,

stores, and uses without informing users about

the duration or retention. The policy is coherent

with the in-depth analysis. However, the content is

relatively condensed (approximately 4,000 words

in English at the time of the study), so it may not

be easily understandable for non-technical users.

Comparing the folders and files from 2018 and

2023 reveals many changes. Several files were

introduced in 2023, such as Advertising, Audible,

and AccountSettings.PrivacyPreferences.Con

sents. These can partly be derived from changes

in the offered services. However, several files

are newly added that contain data from 2018 and

before, such as Digital.Borrows.2 (data from

2014), Digital-Ordering.2 (data from 2012), and

PrimeVideo.Viewing-History (data from 2014).

In total, we find 44 such new files with old content.

4.2 Apple

The DSAReq from Apple has 3 to 11 ZIP files. These

include about 40 to 75 files in 20 to 40 directories

of up to 5 levels nested. The file formats are well-

suited to automatic processing. However, the read-

ability for humans, especially non-technical persons,

is extremely poor. The received data suggests that

Apple stores only necessary data and retains it for a

reasonable duration. Changes to the account infor-

mation (Apple ID Account Information) or App-

Store transactions (Store Transaction History)

seem to be kept infinitely, but this is probably appro-

priate. Remarkably, certain information, like email

addresses, phone numbers, and credit card numbers,

are shown partly redacted, like j***d**@gmail.com.

Apple’s privacy policy is approximately 4,000 words

long and contains detailed information about the col-

lected data, e. g., account information, devices, and

usage information, which seems to follow our data

analysis. The policy also mentions that Apple re-

ceives data from and shares data with other parties,

but it is phrased very vaguely (“Apple may ...”). Our

DSARes did not include any information regarding

shared data. The retention time is not noted, which

makes a comparison difficult. The main structure of

the responses has not changed from 2018 to 2023.

However, new data has been included in the 2023 ver-

sion. For example, recovery devices and devices with

Apple messaging are added to the folder related to

other data. The AppleID account and device informa-

tion folder includes the latest files Apple ID Device

Information.csv and Data & Privacy Request

History.csv containing data from 2018. Similarly,

the folders Game Center and Information about

Apple Media Services are newly introduced, con-

taining data from, for example, 2011.

4.3 Facebook

If the HTML format is chosen during the request,

the main HTML page is similar to Facebook. The

number of folders depends on conversions and me-

dia uploads, with a minimum of 58 folders for in-

formation about ads, apps and websites, connections,

files, logged information, personal information, pref-

erences, security and login information, and activities.

Information about ads comprises data on advertisers

based on activities or information, though partly not

fitting to the user, a deleted blog page, and connected

websites and apps that were removed in 2018. The

timing (GDPR coming into effect) is also notable, as

the users did not use these online services and apps

then. The logged information contains the location

with postal code and timezone, though not intention-

ally added, and interactions starting in 2013, among

others. We again recognize the location in security

and login information, however, less accurate than

in the location data. Logins, sessions, types of ses-

sions, terminated sessions, geolocation, browser fin-

gerprints, known devices, and browser cookies since

2012 or 2011 are logged. Meta’s privacy policy

concerns Facebook, as well as several other Meta

services that may have additional privacy policies.

Qualitative In-Depth Analysis of GDPR Data Subject Access Requests and Responses from Major Online Services

151

The overall structure is user-friendly, explaining ev-

ery item, even with videos (around 13,000 words in

English). We notice that Facebook/Meta claims to

log much data, including the name of the network

carrier, language, timezone, mobile number, IP ad-

dress, download speed, network capacity, informa-

tion about nearby devices, WiFi hotspots, and mouse

movements. This could partly not be verified with

our responses. Information about cookies is rather

generic, and the usage of shadow profiles is hinted at.

However, we could not find information related to the

retention time. Many files and folders have been re-

named, while new files, for example, supervision,

files, preferences (*), logged information (*),

and your-problem-reports, have been included.

Both (*) files seem interesting, as these probably were

stored already in 2018.

4.4 Google

The DSARes of Google (excluding the content of

Google Drive and the uploaded YouTube videos) con-

tains approx. 100 files in approx. 75 directories. For

browsing the DSARes, an HTML page is included

that groups the files into approx. 50 categories. All

files contain a short explanation of their content. Like

Apple, the overall impression is that the amount of

data and storage time are appropriate for most cate-

gories. For example, the recent logins (which also

contain IP addresses and user agent information) are

only stored for approx. half a year while the history

of installation and purchases from the Google Play

Store are stored infinitely. Also, activities like search

history or a list of watched YouTube videos are stored

infinitely. This behavior can be configured in the ac-

count dashboards to no storage of activities or dele-

tion after 18 months for instance. Google’s privacy

policy is similar in length to Meta’s (approximately

14,000 words). It is nicely presented with illustra-

tions, videos, and links to the aforementioned dash-

boards for configuring information access and dele-

tion. However, regarding retention duration, the pol-

icy remains rather vague. Comparing the responses

from 2018 and 2023, we notice that several folders

and files have been renamed.

4.5 LinkedIn

The DSARes from LinkedIn consist only of a set of

CSV files. No human-readable data format or nav-

igation help is provided. The number of files de-

pends upon the features used (e. g., job search), but

it is much smaller than the other services discussed

above. After analyzing the content, we found the fol-

lowing noticeable aspects: Per device/browser, only

the last login is stored by LinkedIn and presumably

only for two years. The file Ads clicked contains

a long (up to 300 entries in our cases) list of times-

tamps (from the last two years) and “ad ids”. The

DSARes contains “facts” that the users have not ex-

plicitly provided but have been inferred by LinkedIn,

e. g., gender or date of birth. LinkedIn’s privacy pol-

icy is approximately 6,000 words long, a mean size

compared to the other services analyzed. The policy

is nicely written, with explanations and links to fur-

ther information. Information on the storage of logins

complies with the data found in the DSARes. The

policy does not mention the two years observed for

login information. The comparison of the responses

does not show many changes.

4.6 Microsoft

We observed severe issues with requesting the

data exports. This included finding the request

form, different paths to requests depending on

the account type (private or business), and au-

thentication codes sent via email that never ar-

rived. The one received DSARes consists of the file

ProductAndServiceUsage.csv with date, end-date,

aggregation, app name, and app publisher. Further

data can be requested separately for Skype, OneDrive,

Microsoft 365, and Microsoft Teams. Data about the

account, usage, and additional services, such as email,

is not included. Therefore, we conclude that Mi-

crosoft is not compliant concerning the request’s pos-

sibility and completeness. Microsoft’s privacy policy

is the longest, with around 44,000 words. This can

partly be explained as it includes the policies of var-

ious products. According to the privacy policy, Mi-

crosoft stores data about interactions, such as device

and usage data, interests, content consumption data,

searches and commands, voice data, texts, images,

contacts and relationships, social data, location data,

and other input. However, we could not find that in

the responses. The cookie information seems incom-

plete, as the third-party cookie information contains

only two generic sentences. Furthermore, we noticed

broken links in the policy. Finally, information related

to retention is missing. In 2018, the only data received

was a short extract about the Skype service. No data

about the account or activities was included. How-

ever, the data in 2023 is not much more. Although

OneDrive is not used, it appears twice. However, no

information about emails or other similar information

can be found.

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

152

4.7 WhatsApp

The DSARes from WhatsApp contains only six

HTML files (plus an index.html file), making it very

easy to browse the information. The included data is

limited to a minimum. The privacy policy for Whats-

App is rather lengthy (approx. 16,000 words). It lists

detailed data types that are collected and stored. This

includes data types not being part of our DSARes,

e. g., battery level and signal strength. The com-

parison between both responses reveals only a few

changes. The most significant difference is that the

data is now shown in a more user-friendly way by us-

ing HTML. Also, more data on the account registra-

tion is provided.

5 EVALUATION

Based on the results, presented in Section 4 and sum-

marized in Tables 3 and 4 in the Appendix, we com-

pare the online services. Table 2 shows an overview

of the results.

DSAReq and DSARes: DSA requests and re-

sponses were possible at most services, although

utilizing desktop browsers was mandatory within

LinkedIn. We observed several issues at Microsoft

that led to only one DSARes being available.

Completeness: Completeness is never given, as

we cannot proof that the online service has provided

us with all the data. We are only sure that Microsoft

did not provide all the data as, for example, the regis-

tration data is missing.

Correctness: Although we evaluate correctness,

we did not use controlled data (P

¨

ohn et al., 2023;

Leschke et al., 2024), but historical data to receive

realistic results. Thereby, we cannot strictly compare

input and output. However, we found suspicious data

at Amazon (outdated addresses deleted previously)

and Facebook (data about a page that seems to be ac-

tive, although deleted previously).

Understandable: Concerning understandable

data, we rate JSON as machine-readable and HTML

as understandable. WhatsApp, LinkedIn, and Face-

book fulfill this criterion, while Amazon, Apple, and

Microsoft are considered incomprehensible.

Data Minimization: For data minimization, we

rate the historical data found during the analysis that

is detailed in Section 5. We noticed that none of the

online services fulfill all the criteria. Microsoft per-

forms worst (only one fulfilled), while WhatsApp per-

forms best (four fulfilled).

The amount of historical data indicates if a ser-

vice complies with the data minimization and stor-

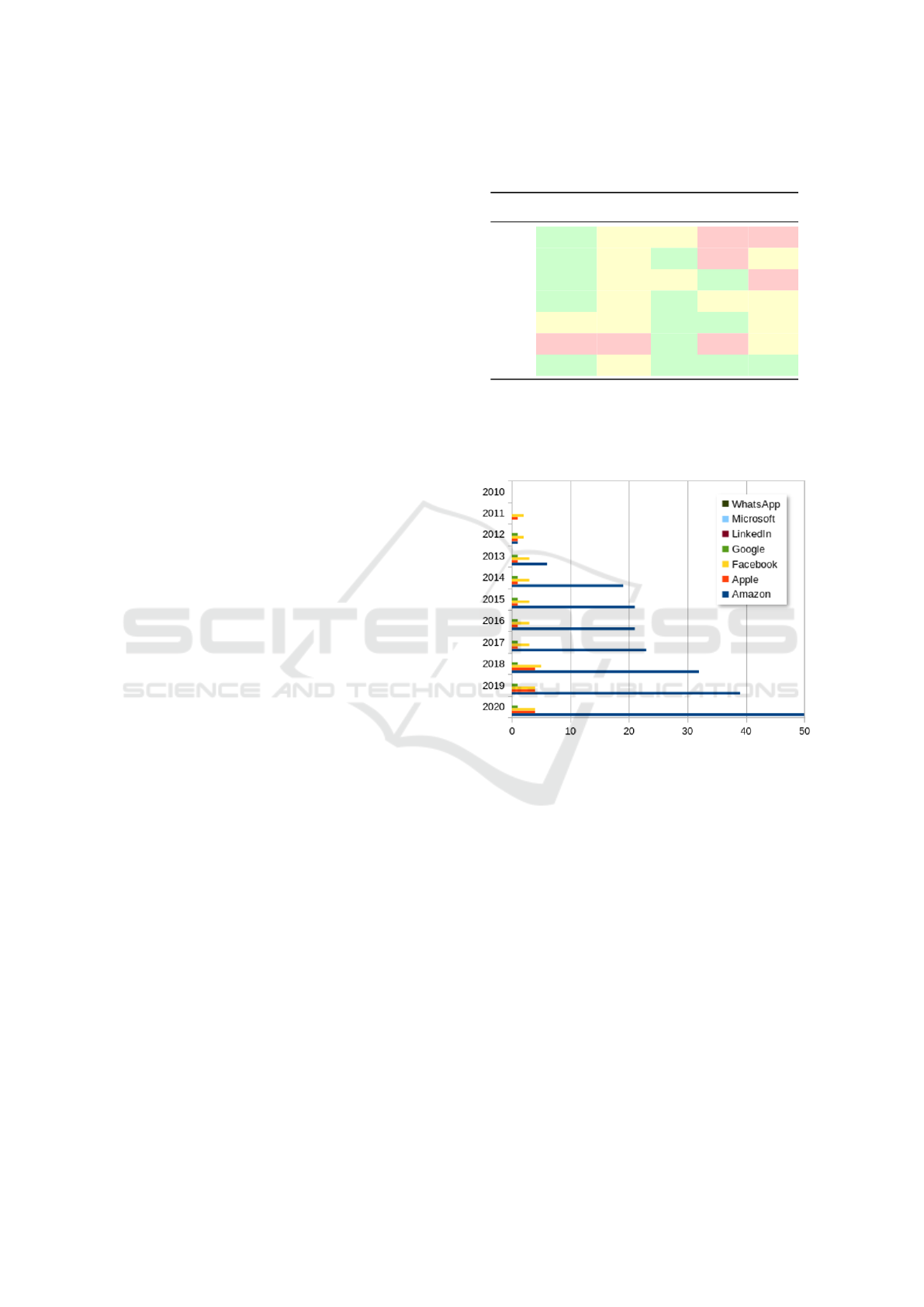

Table 2: Comparison of the online services based on the

evaluation criteria.

DSAR Com. Cor. Und. Min.

Am. + ◦ ◦ – –

Ap. + ◦ + – ◦

FB + ◦ ◦ + –

Go. + ◦ + ◦ ◦

LI ◦ ◦ + + ◦

Mi. – – + – ◦

WA + ◦ + + +

DSAR = DSAReq and DSARes, Com. = Completeness,

Cor. = Correctness, Und. = Understandable, Min. = Data minimization.

Am. = Amazon, Ap. = Apple, FB = Facebook, Go = Google,

LI = LinkedIn, Mi. = Microsoft, WA = WhatsApp.

+ = fulfilled, ◦ = partly fulfilled or unknown, − = not fulfilled.

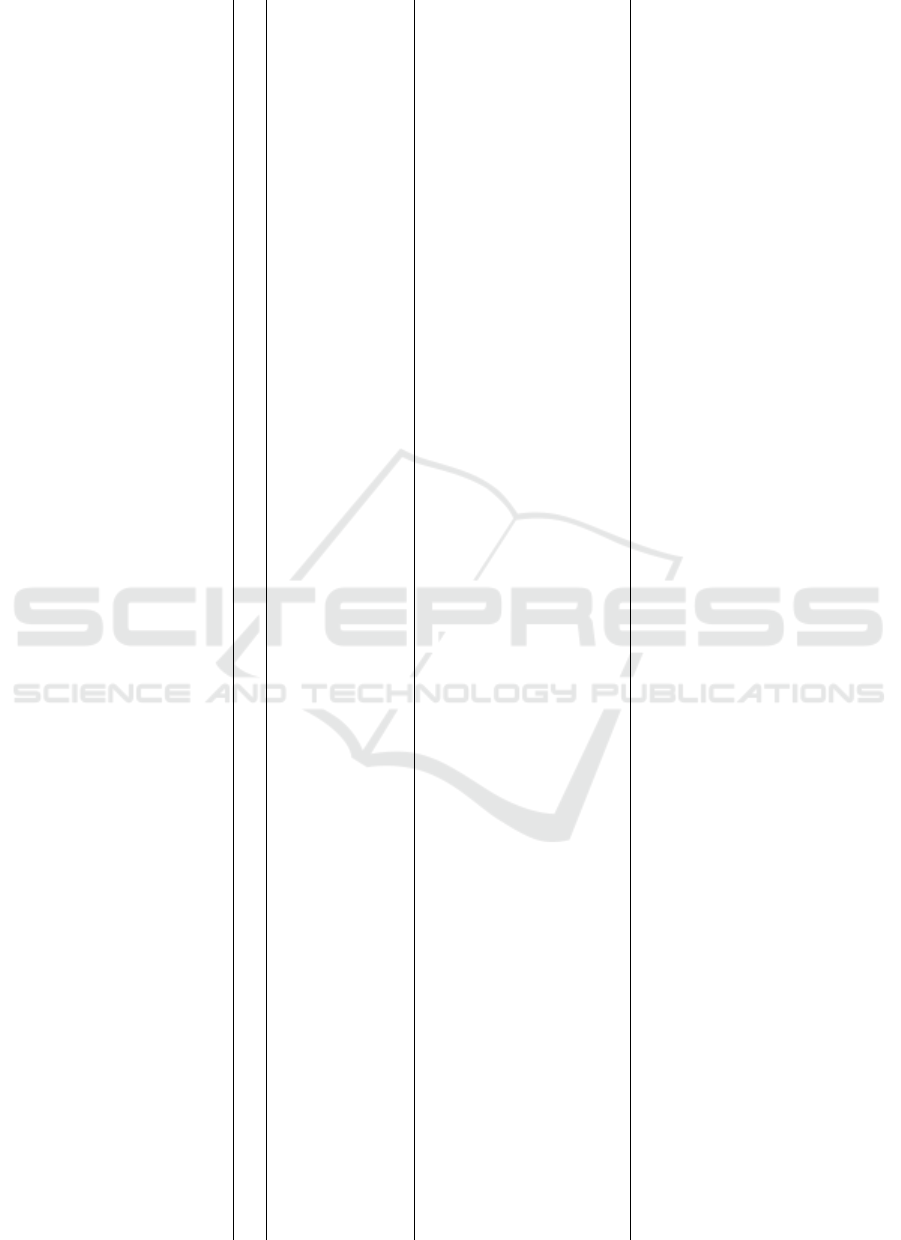

Figure 1: Data with history data by year and online service.

age limitation principles (see Art. 5 GDPR). The re-

sults of the data until 2020 (note that newer data is

not seen as historical) can be seen in Figure 1. We

have found no historical data from 2010 or before,

though some services were used at that time (see Ta-

ble 1). However, data, like cookies and searches, is

included from 2011 and 2012. Generally, most online

services presented us with more data in 2023 due to

newly launched services. Based on the talk by (Letty

and Nocun, 2018), we were not surprised to find more

data in the DSARes of Amazon that should have been

in the one from 2018. We had the same issue with

Apple. For Facebook, we assume the same.

For the most part, the analyzed privacy policies

are easy to understand and sometimes even include

explanatory videos (see Google and Facebook). How-

ever, they do not provide the details to compare them

stepwise with the DSARes, such as the exact data

type. Microsoft is the only online service that clearly

Qualitative In-Depth Analysis of GDPR Data Subject Access Requests and Responses from Major Online Services

153

does not give enough data based on its privacy policy.

The retention time (see Arts. 13 and 15) is typically

not given in the privacy policies. As outlined by (Mo-

han et al., 2019), the GDPR is vague in its interpreta-

tion of deletions (for example, concerning timeliness

and deletion method). We notice the results in the

DSARes, as visualized in Figure 1 (see Section 5).

6 CONCLUSION

The EU’s GDPR grants individuals rights to access

their data and have its usage explained in an elec-

tronic and understandable form. This paper provides

the first qualitative in-depth analysis of the requests

and responses from major online services by analyz-

ing their current data subject access requests and re-

sponses, comparing 2018 and 2023, and comparing

their privacy policies. Overall, the data subject access

process is satisfactory for nearly all services, but the

amount of data varies greatly between the different

services. Also, regarding the accessibility and under-

standability of responses, we experienced large differ-

ences between the services. Further, comparing the

responses from 2018 and 2023 revealed that Amazon

and Apple did not provide all the data in their earlier

responses. Finally, vague information made mapping

the responses with the privacy policies impossible.

REFERENCES

Alizadeh, F., Jakobi, T., Boden, A., Stevens, G., and

Boldt, J. (2020). GDPR Reality Check - Claiming

and Investigating Personally Identifiable Data from

Companies. In Proceedings of the IEEE European

Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (Eu-

roS&PW), Genoa, Italy, September 7–11, 2020, pages

120–129, New York, NY, USA.

Boeschoten, L., Ausloos, J., M

¨

oller, J. E., Araujo, T., and

Oberski, D. L. (2022). A framework for privacy

preserving digital trace data collection through data

donation. Computational Communication Research,

4(2):388–423.

Boeschoten, L., van den Goorbergh, R., and Oberski, D.

(2021a). A set of generated Instagram Data Down-

load Packages (DDPs) to investigate their structure

and content.

Boeschoten, L., Voorvaart, R., Van Den Goorbergh, R.,

Kaandorp, C., and De Vos, M. (2021b). Automatic

de-identification of data download packages. Data

Science, 4:101–120. 2.

Bowyer, A., Holt, J., Go Jefferies, J., Wilson, R., Kirk,

D., and David Smeddinck, J. (2022). Human-GDPR

Interaction: Practical Experiences of Accessing Per-

sonal Data. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference

on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI), New

Orleans, LA, USA, April 29 – May 5, 2022, New York,

NY, USA.

European Parliament (2016). Regulation 71, General Data

Protection Regulation (EU) 2016/679. https://eur-lex.

europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj. Accessed January 6,

2025.

Leschke, N., Kirsten, F., Pallas, F., and Gr

¨

unewald, E.

(2023). Streamlining Personal Data Access Re-

quests: From Obstructive Procedures to Automated

Web Workflows. In Garrig

´

os, I., Murillo Rodr

´

ıguez,

J. M., and Wimmer, M., editors, Web Engineering,

pages 111–125, Cham. Springer Nature Switzerland.

Leschke, N., P

¨

ohn, D., and Pallas, F. (2024). How to Drill

into Silos: Creating a Free-to-Use Dataset of Data

Subject Access Packages. In Jensen, M., Lauradoux,

C., and Rannenberg, K., editors, Privacy Technologies

and Policy, pages 132–155, Cham. Springer Nature

Switzerland.

Letty and Nocun, K. (2018). Arch

¨

aologische Stu-

dien im Datenm

¨

ull – Welche Daten spe-

ichert Amazon

¨

uber uns? https://media.ccc.

de/v/35c3-9858-archaologische\ studien\ im\

datenmull. accessed January 6, 2025.

LinkedIn (2024). About LinkedIn. https://about.linkedin.

com. Accessed January 6, 2025.

Mohan, J., Wasserman, M., and Chidambaram, V. (2019).

Analyzing gdpr compliance through the lens of pri-

vacy policy. In Gadepally, V., Mattson, T., Stone-

braker, M., Wang, F., Luo, G., Laing, Y., and Dubovit-

skaya, A., editors, Heterogeneous Data Management,

Polystores, and Analytics for Healthcare, pages 82–

95, Cham. Springer International Publishing.

Peters, Y., Nehls, P., and Thimm, C. (2023). Plat-

tformforschung mit Instagram-Daten – Eine

¨

Ubersicht

¨

uber analytische Zug

¨

ange, digitale Erhebungsver-

fahren und forschungsethische Perspektiven in Zeiten

der APIcalypse. Publizistik, 68(2):225–239.

P

¨

ohn, D., M

¨

orsdorf, N., and Hommel, W. (2023). Nee-

dle in the Haystack: Analyzing the Right of Access

According to GDPR Article 15 Five Years after the

Implementation. In Proceedings of the 18th Interna-

tional Conference on Availability, Reliability and Se-

curity, ARES ’23, New York, NY, USA. Association

for Computing Machinery.

van Driel, I. I., Giachanou, A., Pouwels, J. L., Boeschoten,

L., Beyens, I., and Valkenburg, P. M. (2022). Promises

and Pitfalls of Social Media Data Donations. Commu-

nication Methods and Measures, 16(4):266–282.

APPENDIX

Table 3 describes the path to the request and the re-

quest itself, while Table 4 contains the notification,

download, and data (without date and time).

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

154

Table 3: Template 1/2 containing data about the path to the request and the request itself.

Categories Amazon Apple Facebook Google LinkedIn Microsoft WhatsApp

(a) Path to request

Starting point Web + App Web + App Web + App Web + App Web + App Web + App App

Steps to request 5 6 7–10 7 5 n 4

Further help required No No No No Partly Yes No

Observations User-friendly Easier in

browser

User-friendly Easier in browser Not possible

within the app

Not intuitive User-friendly

(b) Request

Form of request Form Form Form Form Button Multiple Button

Authentication for

request (*)

L + 2FA L + 2FA L L + Pwd L + MFA L + MFA L

Selection options Categories Categories Categories and

notification

Categories, file

type, frequency

& destination

none services none

Observations User-friendly User-friendly User-friendly User-friendly User-friendly Partly not

possible

User-friendly

(*) L: Logged into account; 2FA: Second-factor authentication; MFA: Multi-factor authentication (at least 3 authentication factors);

Pwd: Additional password.

Qualitative In-Depth Analysis of GDPR Data Subject Access Requests and Responses from Major Online Services

155

Table 4: Template 2/2 containing data about the notification and data.

Categories Amazon Apple Facebook Google LinkedIn Microsoft WhatsApp

(c) Notification and download

Form of information

about data

Email Email Email/In-App Email Email Download In-App

Time between

request and data

available

<3 days <1 week <3 days <1 day <2 days <5 min <3 days

Steps to data 4 5 3 4 4 1 2

Authentication for

data (*)

L + 2FA L + 2FA L L + Pwd L + MFA L L

Observations User-friendly User-friendly Email might

be sent

User-friendly User-friendly Not intuitive User-friendly

(d) Data

Data formats CSV, EML,

JPEG, JSON,

PDF, TXT,

WAV,

README

CSV, ICS,

JSON

JSON or

HTML, TXT,

JPG, PNG,

GIF

HTML, CSV, JSON,

TXT, PDF, MBOX,

VCF, ICS, README,

JPG, PNG, atom, DIC,

DOCX, FRC, GIF, ICO,

MP4, PPTX, XLSX,

XML

CSV CSV HTML,

JSON, PNG

Data type Machine-

readable

Machine-

readable

Both Both Machine-

readable

None Both

Folders/Categories 212 24 296 133 1 0 14

Number of files 15906 51 616 5414 33 1 5

Observations not complete

(*) L: Logged into account; 2FA: Second-factor authentication; MFA: Multi-factor authentication (at least 3 authentication factors);

Pwd: Additional password.

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

156