Raising the Confidence of Mothers in Preterm Birth Care:

Exploring the Secondary Role of the Internet

Jamale S. El-Eid

1a

, Nabil Georges Badr

1b

, Salim M. Adib

1c

and Bernard Gerbaka

2d

1

Higher Institute of Public Health - Faculty of Medicine, Saint Joseph University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon

2

Department of Epidemiology and Population Studies, American University of Beirut, Lebanon

Keywords: Preterm Birth, NICU Training, Knowledge Acquisition, Role of Internet.

Abstract: Adequate family education and knowledge regarding basic preterm baby care is essential to enhance parents’

experience and alleviate the quality of life with preterm babies. Our study looks at the extent to which

knowledge affects the confidence of new mothers. It explores other potential factors, sources of knowledge,

and the role of technology and online content. The research model for our empirical investigation takes the

foundations of the knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) theory as the central survey framework of the

theory of planned behaviour. The study results showed that NICU training has a significant impact on mothers'

knowledge levels regarding the care of preterm babies after their discharge from the NICU. Findings revealed

a prevalent reliance on unofficial online sources such as Google, social media, and other informal websites,

rather than official resources like the WHO, CDC, or similar trusted platforms. Knowledge level emerged as

a significant predictor of the dependent variable, maternal confidence, with a predictability score of 43.6%.

This suggests that improved knowledge fosters greater confidence, particularly among first-time mothers who

often rely on secondary internet sources to bridge their knowledge gaps and boost their confidence. These

findings highlight opportunities for healthcare providers and health authorities to improve information

generation and dissemination and foster support systems for parents.

1 INTRODUCTION

Every year more than 15 million tiny creatures are

born prematurely or earlier than their expected

arrival. Pre-term birth or Premature birth (PB) refers

to births that occur earlier than 37 weeks or equivalent

to 259 days of gestation. It accounts for more than one

million neonatal deaths per year at the global level

1

And presents a major challenge to perinatal health as

it significantly contributes to various morbidities that

may extend to adulthood (Pinto F.a, 2019). PB may

drastically affect the little bundles of joy, their

mothers, and family members caring for them

(O'Donovan & Nixon, 2019).

Adequate family education and knowledge

regarding the basic preterm baby care is essential to

enhance parents’ experience and alleviate the quality

of life with the preemie (Sedigheh Khanjari, 2022).

This is when parents become the primary caregivers

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2698-5269

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7110-3718

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8831-2954

who provide the basic and sometimes more

complicated care that may require a certain level of

training and monitoring (José Granero-Molina,

2019). Understanding parents’ challenges and the

support they need would help achieve optimal

outcomes for babies (Ma RH, 2021; Amorim, 2018).

In 2012, the prevalence of preterm births in

Lebanon was around 9.6% as per the National

Collaborative Perinatal Neonatal Network (NCPNN)

which analysed 35% of the national birth data. This

accounts for around 8656 neonates per year of the

total 90,167 births reported by the Ministry of Public

Health.

We are interested to learn about the extent to

which knowledge affects the confidence of the new

mothers attitude and explore the relevant indicators

for that. We aim to explore the sources of knowledge

parents seek for care of their preterm babies in a

context of a Low-or Middle-Income Country (LMIC)

d

https://orcid.org/0009-0002-5755-6862

1

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/

preterm-birth

372

Badr, N. G., El-Eid, J. S., Adib, S. M., Gerbaka and B.

Raising the Confidence of Mothers in Preterm Birth Care: Exploring the Secondary Role of the Internet.

DOI: 10.5220/0013099300003911

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 2: HEALTHINF, pages 372-381

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

like Lebanon, where resources are scarce and

research is limited. Furthermore, as Information and

Communication Technology (ICT) modalities, also

known as digital tools, are becoming more popular,

employing them to educate and support parents of

preterm babies would be a way forward to address

those needs. Preterm birth disproportionately affects

minority and low-income groups and is associated

with high infant morbidity and mortality rates. In the

neonatal intensive care unit and elsewhere in the

postpartum period, healthcare teams can use digital

solutions to fulfil the needs of mothers and infants

(Jani, et al, 2021). Solutions like e-health,

telemedicine, and digital education can also be

substantial to secure support to health centres and

patients in rural areas and maybe less developed

countries who have little access to advanced facilities

(Ruxwana NL, 2010). Our research question explores

the extent that new mothers rely on the use of

information and communication technology ICT,

digital resources, and how they are combined with

direct training of parents caring for their preterm

babies after they are discharged from the NICU.

2 BACKGROUND

We are interested to explore the extent to which

knowledge affects attitude and explore the relevant

indicators for that. We set the stage for our empirical

investigation through a research model that takes the

foundations of the theory of knowledge, attitudes, and

practices (KAP) theory as the central survey

framework of the theory of planned behaviour

(Ajzen, I. 2011), Fig 1.

Figure 1: KAP Conceptual Model from Ajzen, I. (2011).

The theory postulates that knowledge acquisition

modifies human health-related behaviors in preterm

postnatal care (Herzog-Petropaki et al, 2022; Parker

et al, 2020; McMillan et al, 2009). We follow the

example of other research in this context to

understand mother’s confidence and competency in

preterm infant care (Kusumaningrum et al, 2019;

Bajoulvand et al, 2019; Hwang et al, 2023). Our

choice of KAP theory and model offers a deeper dive

into antecedents of knowledge and attitudes and

investigate knowledge levels acquired from online

information sources, NICU training and other factors

would influence the confidence of preterm infants’

mothers, especially testing for the impact of the ICT

use and online information sources that these new

mothers find relevant.

3 RESEARCH MODEL

3.1 Antecedents and Hypotheses

3.1.1 Confidence/ Attitude

The confidence of new mothers in caring for their

preterm baby has a significant impact on their ability

to handle their preemie at home. Maternal confidence

alleviates self-empowerment and capability in

handling the caretaking tasks with less stress and

anxiety (Premji, 2018). Mothers’ attitude and

confidence in taking control over caring for their

preterm baby at home is highly affected by the level

of knowledge and education they have (Parhiz Z,

2016). As such, mothers of preterm infants rather feel

unprepared to assume the full responsibility for their

babies after their discharge from the NICU because

they lack the proper education and confidence

(Kadiroğlu, 2021). Hence, inadequate knowledge of

mothers about caring for their preterm babies would

in turn associate with post-discharge complications

and sometimes readmission (Aldirawi, 2019). Our

inquiry into the confidence level of the new mothers

is modelled after Rinehimer, M. A. (2017), we

attempt to detect the new mother’s comfort

interacting with their infant at home, their reliance on

the information received and their understanding of

the baby’s developmental milestones.

We build a model (Fig. 2) where Confidence is the

dependent variable (CONF 4.1 – 4.10).

Figure 2: Our Model.

We consider the following variables as latent

independent variables:

(KNOW_LVL) - Scored knowledge level as

reported by the survey instrument (See Appendix)

(NICU_T1 – T10) - Represents the training

provided by NICU staff to preterm mothers

(INFO_SOURCE) – designates the source of

information on caring for preterm infant and whether

Raising the Confidence of Mothers in Preterm Birth Care: Exploring the Secondary Role of the Internet

373

it is official online sources/websites like the World

Health Organization, Center for Disease Control, and

other scientific societies (ONLINE_1); or unofficial

online sources like Google and other websites and

mobile applications (ONLINE_2) and finally (F&F) -

Family and friends.

(ICT_USE) is the variable that represents the use

of electronic platforms or mobile applications by new

mothers to get care information. Finally,

(EXT_FACTORS), include factors such as Maternal

age (AGE); Education level (EDU); length of the

infant stays in the NICU (NICU_DAYS) and whether

this was the mother’s first pregnancy (1ST_PREG).

3.1.2 NICU Training

Patient and family education is a core practice in

health care to improve health outcomes and foster

self-efficacy and confidence. When empowered with

knowledge about their health situation, treatment and

preventive alternatives, patients and their families

become more engaged in their care plan, which

positively affects their adherence (Paterick TE,

2017). Structured family-centred education of the

mothers and fathers not only improves the health

outcomes of the baby but also enhances the quality of

life of parents (Sedigheh Khanjari, 2022). Patient and

Family Education in general, and care for babies on

specific is highly recognized as a basic requirement

in Lebanon's Hospital national accreditation

standards under the Patient and Family Rights

domain. Hospitals are required to establish policies,

procedures, and mechanisms to realize this

requirement and put in place measures to assess its

effectiveness. Discharge education for NICU

graduates constitutes fundamental care aspects like

basic care, feeding, follow-up care among others

(Sedigheh Khanjari E. F., 2022). Our first (H1)

hypothesis states that NICU training, as a

fundamental knowledge base, is an important

antecedent to increasing the knowledge level of new

mothers in the care of their preterm infant.

3.1.3 Sources of Information

Upon the transition of the preterm baby home after

spending days or weeks in the NICU, parents

experience a significant level of anxiety and stress to

face the responsibility of being the primary caregivers

to the baby (Abiuty Omwenga Omweri, 2024). After

being passive recipients of information while at the

NICU, they become active seekers of various types of

information as they move home. Parents explore a

wide range of information from various sources

including computer-based or digital resources to fulfil

their needs in caring for the preterm baby at home

(Brazy, 2001). For instance, social media platforms,

like Google Search (Dol et al, 2019) and Facebook,

are reported as frequently utilized resources to look

out medical information and seek advice (Taylor K,

2023; Erika Frey, 2022). We are also interested in

exploring the interest in information available from

official health authority websites like the World

Health Organization (WHO), Centre for Disease

Control (CDC), National Health Authorities, Medical

Societies, which might be seen as a triangulated

source that might have a certain degree of reliability

and usefulness.

For our model, we therefore hypothesize (H2),

that, information sources on caring for preterm

infants are antecedents to increasing the knowledge

level of new mothers in the care of their preterm

infant. These sources could be either official online

sources/websites like the World Health Organization,

Center for Disease Control, and other scientific

societies, or unofficial online sources like Google and

other websites and mobile applications. They also

could be information offered by friends and family

members.

3.1.4 Knowledge Acquisition

For the third hypothesis, H3, we postulate the

knowledge level of new mothers is an important

antecedent to their confidence level in caring for their

preterm infants.

Parents of preterm babies need a wide range of

support services, among which education and

information prevail. The results of a systematic

review published in 2011 by Brett et al reflected that

parents of preterm babies need accessible,

individualized, and up-to-date education programs to

help them cater to their baby’s needs and support their

development (Brett J, 2011). Traditional education

and training programs that include physical presence

and face-to-face meetings may help parents to some

extent however, they also incur several logistical

challenges that affect the level of attendance and

response (Valérie Lebel, 2021). In addition,

educational resources that include verbal education

and/or printed pamphlets may not account for the

factors of interaction, individualization, and parents’

stress and well-being (Valérie Lebel, 2021).

For our inquiry, we conducted a desktop review

of available guidelines and resources for the basic

care information that parents should know about

caring for their preterm baby after discharge from the

NICU. We compiled references of publications by

(Furtak, 2021; WHO, 2022), and triangulated our

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

374

information by articles of the American Academy of

Paediatrics parenting website

2

, Canadian Paediatric

Society, Foetus and Newborn Committee, Alberta

Health Services

3

, and the Center for Disease

Prevention and Control

4

. We use these references to

build a questionnaire that would explicitly assess the

level of knowledge parents acquire on basic preterm

baby care. We run our questionnaire by 30 preterm

babies’ parents and neonatal care practitioners to

obtain a relative validation or the relevance of the

questions (Appendix).

3.1.5 Use of Technology Tools

Digital tools may offer comfort, adaptability and

autonomy in providing care and the effectiveness of

care. The literature advocates including parents or

primary caregivers of infants requiring care in a

neonatal intensive care unit, when assessing the

relevance of exploiting technology in the circle of

care (Dol et al, 2017; Gibson, 2020). These

technologies include means of education (e.g. web-

based platforms, mobile applications);

communication (e.g. videos, SMS or text messaging),

or a combination of both.

The design and implementation of perinatal

eHealth programs are emerging as the availability of

new eHealth systems (i.e. applications and machine

learning-based tailored feedback), and ubiquitous

devices (i.e. smartphones and wearables) increases

(Auxier et al, 2023). Parents are open to using

technology as part of their neonatal intensive care;

videoconferencing for instance, is sought after

discharge as a means of providing post-departure

family assistance. We then propose the hypothesis

(H4), that the use of electronic platforms or mobile

applications by the new mothers to get care

information is an important antecedent to their

confidence level in caring for their preterm infants.

3.1.6 External Factors

Our last latent variable summarizes potential external

factors of determinants of health, namely age and

education that may have an influence on the

confidence of mothers to care for caring for a preterm

baby after discharge from the hospital (Taraban and

Shaw, 2018). The length of the NICU stay would

affect the parents' confidence given the exposure that

the parents get while shadowing the health care

practitioners in the NICU and whether the preterm

baby is their first-born (Pinar & Erbaba, 2020). That

2

HealthyChildren.org, 2023

3

www.albertahealthservices.ca/scns/page10303.aspx

said, our last hypothesis (H5) is that external factors

such as maternal age, education, length of the infant

stay in the NICU and whether this was the mother’s

first pregnancy are important antecedents to their

confidence level in caring for their preterm infants.

3.2 Approach and Study Design

We follow a convenience sampling using data on 26

public and private hospitals that offered NICU

services in two of the largest districts in Lebanon,

Mount Lebanon (suburb to the capital) and Beirut.

The target population included Lebanese parents with

preterm babies born earlier 37 weeks of gestation.

After securing the required ethical approvals, we

conducted the study between December 2023 and

September 2024. We approached all mothers who fit

the inclusion criteria in coordination with the NICU

health doctors or nurses within the discharge week.

We enrolled preterm mothers immediately after

delivery and contacted again 6-8 weeks after

discharge to partake the survey.

Our survey instrument comprises seven sections

(Appendix). In the first section, we collect 37 answers

to questions and summarize the score into three

knowledge levels as preliminary level (scores of

<50%), average (Scores 50% - 75%) and advanced

(scoring 75% - 100%). Upon data collection we

normalize our answers to produce our KNOW_LVL

variable values of (0, 1, and 2) respectively (Peterson

and & Cavanaugh, 2020). Section 2 explores the pre-

discharge training that parents were offered in the

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). Section 3 asks

the participants to identify the sources they found

helpful to preterm baby care. Next, section 4

investigates new mothers’ attitudes and confidence

level regarding caring for preterm baby. Participants

were able to report whether they use electronic

platforms or mobile applications to get information

about caring for their baby in section 5. Finally,

sections six and seven attempt to capture external

factors such as maternal age, education, whether it

was a case of first pregnancy and the length of stay of

preterm baby in the NICU.

4 STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The participants were mothers fitting the below

profile (Table 1). In an interestingly symmetrical

normal distribution, our sample show that mothers

4

www.cdc.gov/maternal-infant-health/about/index.html

Raising the Confidence of Mothers in Preterm Birth Care: Exploring the Secondary Role of the Internet

375

(N=78) with an average age of 32, 68% on their first

pregnancy, gave birth to their preterm baby within the

first 2 weeks of gestation.

Table 1: Sample Profile.

N=78 Avera

g

e Median Mode

Maternal a

g

e in

y

ears 32 32 32

Gestational age

(completed weeks) 31 32 33

First Pre

g

nanc

y

68%

4.1 Measurement Model Analysis

We loaded our model in SmartPLS3.0 and ran the

PLS algorithm. We then reduced the indicator

variables in order to reach convergent validity and

reliability. We accepted only the indicators with

loadings ≥ 0.708 as significant (Hair et al, 2019).

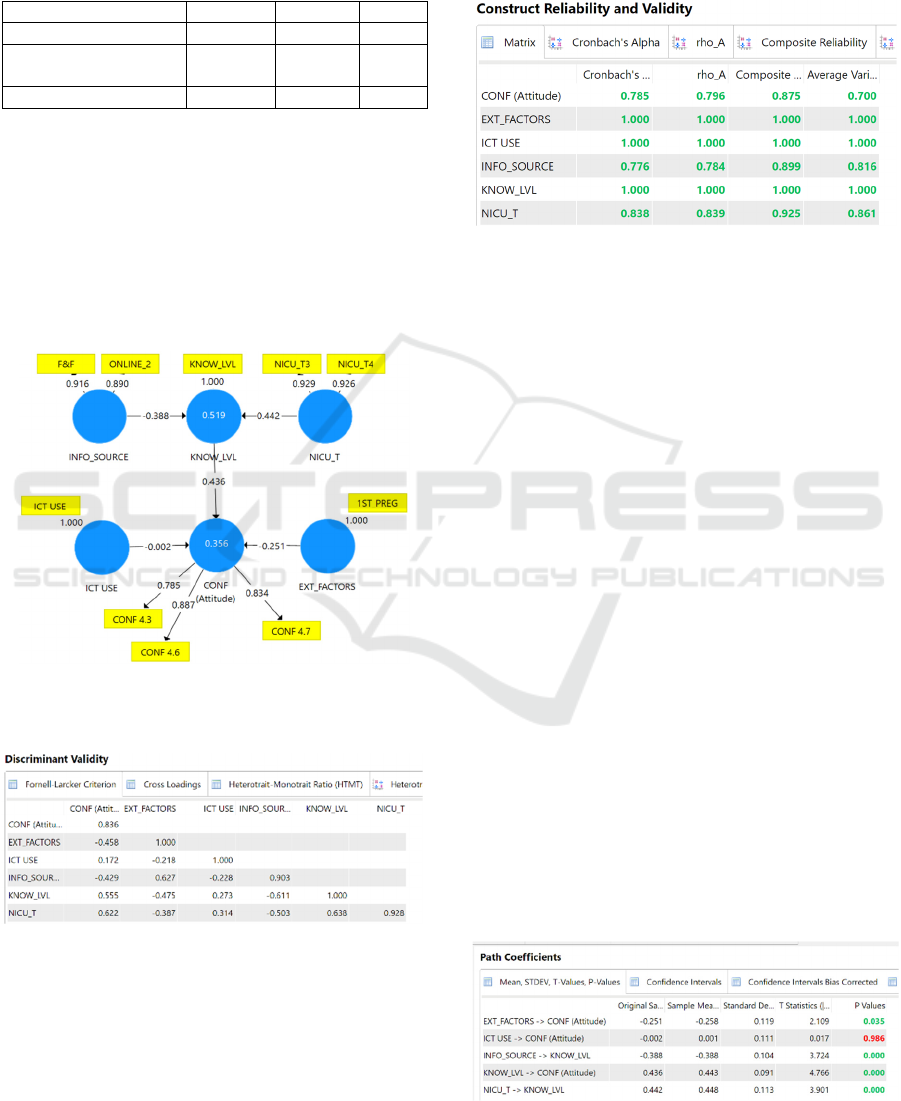

Figure 3 shows our valid model - with outer loading

factors.

Figure 3: Valid Model - with outer loading factors.

Table 2: Discriminant Validity.

The model is of a reflective construct; therefore,

construct validation can be obtained through

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) (i.e. convergent

and discriminant validity) and reliability testing (i.e.

Cronbach's Alpha) (Hair et al, 2019). We find that the

model has good discriminant validity since the AVE

squared value of each exogenous construct (the value

on the diagonal) exceeds the correlation between this

construct and other constructs - see Fornell-Larcker

Criterion Values in Table 2 (values below the

diagonal).

Table 3: Construct Reliability and Validity.

Subsequently, following Hair et al (2019), we

perform a convergent validity test by looking at the

loading factor value of each indicator against the

construct. We accept the indicators with loadings of

≥ 0.708 as significant with an AVE value for each

construct > 0.5. Subsequently, we assess the construct

reliability. The reliability test results in table 3 show

that all constructs have composite reliability and

Cronbach's alpha values greater than 0.7 (Hair et al,

2019). In conclusion, all constructs have met the

required validity and reliability.

Further, our model produced R2 values of .519

and .356 for Knowledge level and Confidence. These

moderate to substantial values reinforce the value of

our study and the findings (Hair et al, 2019). They

indicate that 51.9% of the variability in the outcome

in Knowledge Level and 35.6 % of the variability in

the confidence latent variable may be explained by

this study.

4.2 Supported Hypotheses

We found that two significant indicators inform the

NICU Training latent variable in our model. These

indicators relate to training on how to interact with

the preterm baby (NICU_T4) and how to position the

preterm baby in bed (NICU_T3). NICU training as a

fundamental knowledge base is an important

Table 4: Bootstrapping results.

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

376

antecedent to increasing the knowledge level of new

mothers in the care of their preterm infant (H1).

Table 4 provides evidence of the statistical

findings to support hypothesis H1, H2, H3 and H5.

Information sources on caring for preterm infants

are antecedents to increasing the knowledge level of

new mothers in the care of their preterm infant (H2).

Mothers of preterm babies found information on

caring for their preterm baby from unofficial online

sources like Google and other websites and mobile

applications. Some have received information from

family and friends. What is interesting is that

information sources from official bodies such as

WHO or CDC did not seem as relevant.

The knowledge level of mothers with preterm

infants emerged as a significant predictor of maternal

confidence, with a predictability score of 43.6%.

Improved knowledge fosters greater confidence,

particularly among first-time mothers who often rely

on secondary internet sources to bridge their

knowledge gaps and boost their confidence.

To that effect, the knowledge level of new

mothers is an important antecedent to their

confidence level in caring for their preterm infants

(H3). They believe that the information and

instructions they received from the NICU are

sufficient to meet their needs to care for their preterm

baby (CONF 4.3), the general knowledge they

acquired through the varied sources have increased

their understanding of their baby’s developmental

milestones (CONF 4.6). They are confident that they

know how to care for their newborn and the details of

follow-up assessments needed following discharge.

Our model analysis supports this hypothesis with a

predictability of 43.6 % (path coefficient = 0.436) and

high level of confidence (t= 4.766).

The maternal age, education, length of the infant

stay in the NICU, are not significant indicators.

However, the fact whether this was the mother’s first

pregnancy was important antecedent to their

confidence level in caring for their preterm infants

with a predictability of 25.1 % (path coefficient = -

0.255) and high level of confidence (t= 2.109).

Finally, there was no support for the hypothesis

that the use of electronic platforms or mobile

applications by the new mothers to get care

information is an important antecedent to their

confidence level in caring for their preterm infants.

5 RESULTS AND CONCLUSION

In summary, our effort identified support for four

hypotheses (H1, H2, H3 and H5) while H4, that states

the use of electronic platforms or mobile applications

by the new mothers to get care information is an

important antecedent to their confidence level in

caring for their preterm infants, was not supported.

We find our results surprising. Information sources

from official bodies, such as WHO or CDC were not

found as relevant. Additionally, using formal

electronic platforms was not an important factor

affecting new mothers’ confidence in caring for their

preterm infants. While, an essential source of

knowledge is still the support of friends and family,

mothers of preterm babies found information on

caring for their preterm baby from unofficial online

sources like Google and other websites and mobile

applications. Nevertheless, the study demonstrates

that NICU training has a significant impact on

mothers' knowledge levels regarding the care of

preterm babies after their discharge from the NICU.

This aligns with the knowledge, attitudes, and

practice (KAP) framework, where knowledge serves

as a critical foundation for shaping positive attitudes

and informed practices.

5.1 Emerging Crowdsourcing Platform

The internet promises to be an effective

crowdsourcing platform among preterm baby

mothers. By exploring the dynamics of how mothers

seek and utilize knowledge for the care of their

preterm baby(ies), the study provides valuable

insights into the complexities of knowledge

acquisition in terms of how mothers of preterm

infants acquire and use knowledge, particularly

highlighting the unexpected prominence of unofficial

online sources like google and social media. Mothers'

attitudes toward credible sources and the accessibility

or perceived relevance of the preference to seek non-

official information underscore the mothers'

information-navigation habits and the importance of

fostering effective management of crowdsourced

online information. Our findings highlight

opportunities for healthcare providers and health

authorities to improve information generation and

dissemination and eventually fostering support

systems for parents. One could propose forums and

open-source blogs that collect, disseminate, and

connect information from preterm baby mothers, and

help shape better support systems. Such a

sociotechnical approach could integrate unofficial

experiences, sourced from preterm mothers for the

support of their peers focused on the specific needs of

these parents.

What was not surprising, was the finding that

women on their first pregnancy have found a source

Raising the Confidence of Mothers in Preterm Birth Care: Exploring the Secondary Role of the Internet

377

of confidence boost in searching secondary sources

on the Internet. The internet is rich with informal sites

on neonatal care (Alderdice, et al, 2018). Albeit, the

quality of information in these sources may not be

verified, they seem to offer a confidence level boost

to mothers. For the setting of our study, we issue a

genuine invitation to the Lebanese National Health

Authority in collaboration with the health care

organizations to enhance their online presence and

support parents with the consistent information and

advice in terms of handling preterm babies after

discharge from the NICU.

5.2 Limitations and Further Research

The sample size used is narrow. Nonetheless, it is

effective in supporting our study. A retrospective

sample size verification using the minimum R

squared method showed that our sample size was

satisfactory (Kock, and Hadaya, 2018).

Still, the use of convenient sampling, in terms of

choosing two of the most populous districts among

the other districts of Lebanon to conduct the study,

may bring forth a form of bias. The study was

conducted in Beirut and Mount Lebanon only which

may not represent all regions of Lebanon, especially

the rural ones. However, Mount Lebanon, which is

the largest district, includes some rural areas,

especially in the mountain villages that are relatively

far from the capital cities. Nevertheless, our sampling

was inclusive to all hospitals who offer NICU

services in these two districts and were invited to take

part in the study and while exhaustive sampling was

used to reach out to every potential candidate who is

eligible to participate.

As such, our study captures insights from parents

of preterm babies residing in these rural areas.

Simultaneously, parents seeking neonatal services at

the referral hospitals in Beirut and Mount Lebanon

come from diverse regions in Lebanon including

areas outside these two big districts.

Acknowledging that the empirical part of this

effort was still in progress at the time of writing this

paper, we were motivated by interesting findings

from the questionnaire section of this study that

mothers' reliance on informal online sources to seek

information regarding their preterm babies, we

decided to disclose these findings early as they could

provide valuable insights and prompt timely

discussions on this critical aspect of information-

navigation or seeking behaviors.

We are proceeding with an extension of the

sample to other geographies of the country, while

adding a qualitative extension for the inquiry, to

deepen the understanding of the matter. Once

complete, we will share the expanded findings, as we

are positive, will shed more light on the complex

subject of preterm birth care.

REFERENCES

Abiuty Omwenga Omweri, M. L. (2024, January).

Caregivers’ Experiences in Providing Home Care for

Preterm Infants during the Initial Six Months Post-

Discharge from the Neonatal Care Unit. JCMA.

Ajzen, I. (2011). The theory of planned behaviour:

Reactions and reflections. Psychology & Health, 26(9),

1113–1127.

Alderdice, F., Gargan, P., McCall, E., & Franck, L. (2018).

Online information for parents caring for their

premature baby at home: a focus group study and

systematic web search. Health Expectations, 21(4),

741-751.

Aldirawi, A.,. -K. (2019). Mothers’ Knowledge of Health

Caring for Premature Infants after Discharge from

Neonatal Intensive Care Units in the Gaza Strip,

Palestine. Open Journal of Pediatrics, 9, 9(3), 239-252.

Amorim, M. S.-I. (2018). Quality of life among parents of

preterm infants: a scoping review. Qual Life Res, 1119–

1131.

Auxier, J., Savolainen, K. T., Bender, M., Rahmani, A. M.,

Sarhaddi, F., Azimi, I., & Axelin, A. M. (2023).

Exploring access as a process of adaptation in a self-

monitoring perinatal ehealth system: Mixed methods

study from a sociomaterial perspective. JMIR

Formative Research, 7, e44385.

Bajoulvand, R., González-Jiménez, E., Imani-Nasab, M.

H., & Ebrahimzadeh, F. (2019). Predicting exclusive

breastfeeding among Iranian mothers: application of

the theory of planned behavior using structural equation

modeling. IJNMR, 24(5), 323-329.

Brazy, J.,. (2001). How Parents of Premature Infants Gather

Information and Obtain Support. Neonatal Network,

20(2).

Brett J, S. S. (2011). A systematic mapping review of

effective interventions for communicating with,

supporting and providing information to parents of

preterm infants. BMJ Open.

Callander, E. A. (2021, July). The healthcare needs of

preterm and extremely premature babies in Australia—

assessing the long-term health service use and costs

with a data linkage cohort study. Eur J Pediatr, 2229–

223.

Dol J, R. B.-Y. (2019). Learning to parent from Google?

Evaluation of available online health evidence for

parents of preterm infants requiring neonatal intensive

care. Health Informatics Journal, 25(4), 1265-1277.

Erika Frey, C. B. (2022). Parents’ Use of Social Media as a

Health Information Source for Their Children: A

Scoping Review. Academic Pediatrics, 22(4), 526-539.

Furtak, S. L., Gay, C. L., Kriz, R. M., Bisgaard, R., Bolick,

S. C., Lothe, B., ... & Franck, L. S. (2021). What parents

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

378

want to know about caring for their preterm infant: a

longitudinal descriptive study. Patient education and

counseling, 104(11), 2732-2739.

Gibson, C., Ross, K., Williams, M., & de Vries, N. (2021).

The experiences of mothers in a neonatal unit and their

use of the babble app. Sage Open, 11(2),

21582440211023170.

Guo, J. L., Wang, T. F., Liao, J. Y., & Huang, C. M. (2016).

Efficacy of the theory of planned behavior in predicting

breastfeeding: Meta-analysis and structural equation

modeling. Applied Nursing Research, 29, 37-42.

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M.

(2019). When to use and how to report the results of

PLS-SEM. European business review, 31(1), 2-24.

Herzog-Petropaki, N., Derksen, C., & Lippke, S. (2022).

Health behaviors and behavior change during

pregnancy: Theory-based investigation of predictors

and interrelations. Sexes, 3(3), 351-366.

Hwang, S. S., Parker, M. G., Colvin, B. N., Forbes, E. S.,

Brown, K., & Colson, E. R. (2021). Understanding the

barriers and facilitators to safe infant sleep for mothers

of preterm infants. J Perinatol., 41(8), 1992-1999.

Jani SG, Nguyen AD, Abraham Z, Scala M, Blumenfeld

YJ, Morton J, Nguyen M, Ma J, Hsing JC, Moiwa-

Grant M, Profit J, Wang CJ. PretermConnect:

Leveraging mobile technology to mitigate social

disadvantage in the NICU and beyond. Semin Perinatol.

2021 Jun; 45(4):151413.

José Granero-Molina, I. M.-S.-P. (2019). Experiences of

Mothers of Extremely Preterm Infants after Hospital

Discharge. Journal of Pediatric Nursing.

Kadiroğlu, T. G. (2021). Effect of Infant Care Training on

Maternal Bonding, Motherhood Self-Efficacy, and

Self-Confidence in Mothers of Preterm Newborns.

Matern Child Health J, 40(4), E18–E37.

Kock, N. & Hadaya, P. (2018). Minimum samples size

estimation in PLS-SEM: The inverse square root and

gamma exponential methods. Inf. Syst. J, 28(1), 227-261.

Kusumaningrum, T., Kurnia, I. D., & Doka, Y. P. (2019,

March). Factors Related to Mother’s Competency In

Caring For Low Birth Weight Baby Based on Theory

of Planned Behavior. In IOP Conference Series: Earth

and Environmental Science (Vol. 246, No. 1, p.

012029). IOP Publishing.

Ma RH, Z. Q. (2021, Nov). Transitional care experiences of

caregivers of preterm infants hospitalized in a neonatal

intensive care unit: A qualitative descriptive study.

Nurs Open, 8(6), 3484-3494.

McMillan, B., Conner, M., Green, J., Dyson, L., Renfrew,

M., & Woolridge, M. (2009). Using an extended theory

of planned behaviour to inform interventions aimed at

increasing breastfeeding uptake in primiparas

experiencing material deprivation. British Journal of

Health Psychology, 14(2), 379-403.

Parhiz, Z., Birjandi, M. H., Khazaie, T., & Sharifzadeh, G.

(2016). The effects of an empowerment program on the

knowledge, self-efficacy, self-esteem, and attitudes of

mothers of preterm neonates. Modern Care Journal,

13(3).

Parker, M. G., Hwang, S. S., Forbes, E. S., Colvin, B. N.,

Brown, K. R., & Colson, E. R. (2020). Use of the theory

of planned behavior framework to understand

breastfeeding decision-making among mothers of

preterm infants. Breastfeeding Medicine, 15(10), 608-

615.

Paterick TE, P. N. (2017). Improving health outcomes

through patient education and partnerships with patient.

Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent, 30, pp. 112-113.

Peterson, R. A., & Cavanaugh, J. E. (2020). Ordered quantile

normalization: a semiparametric transformation built for

the cross-validation era. Journal of applied statistics.

Pinar & Erbaba, (2020). Experiences of new mothers with

premature babies in neonatal care units: A qualitative

study. J Nurs Pract, 3(1), 179-185.).

Pinto F.a, c. ·. (2019). Born Preterm: A Public Health Issue.

Portuguese Journal of Public Health.

Premji, S. S. (2018). Mother’s level of confidence in caring

for her late preterm infant: A mixed methods study.

Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27, e1120–e1133.

Rinehimer, M. A. (2017). Investigating the Needs of

Parents of Premature Infants’ Interaction in the

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Seton Hall University

Hall Dissertations and Thesis.

Ruxwana NL, H. M. (2010). ICT applications as e-health

solutions in rural healthcare in the Eastern Cape Province

of South Africa. Health Inf Manag, 39(1), 17-26.

Sedigheh Khanjari, E. F. (2022). The effect of family-

centered education on the quality of life of the parents

of premature infants. J Neonatal Nurs, 26(6), 407-412.

Taraban, L., & Shaw, D. S. (2018). Parenting in context:

Revisiting Belsky’s classic process of parenting model

in early childhood. Developmental Review, 48, 55-81.

Taylor K, H. J. (2023). Social Media as a Source of Medical

Information for Parents of Premature Infants: A

Content Analysis of Prematurity-Related Facebook

Groups. American Journal of Perinatology, 1629-1637.

Valérie Lebel, M. H. (2021). The development of a digital

educational program with parents of preterm infants

and neonatal nurses to meet parents educational needs.

Journal of Neonatal Nursing, 27(1), 52-57.

WHO (2022), Recommendations for Care of the Preterm or

Low Birth Weight Infant ISBN: 978-92-4-005826-2

Wong, K. K. K. (2013). Partial least squares structural

equation modeling (PLS-SEM) techniques using

SmartPLS. Marketing Bulletin, 24(1), 1-32.

Yang M, C. H.-A. (2023, May). Neonatal health care costs of

very preterm babies in England: a retrospective analysis

of a national birth cohort. BMJ Paediatr Open, 7(1).

APPENDIX

Section 1. Knowledge Level Score (KNOW_LVL):

Possible answers: Agree=1 Disagree=0

2.1- The preterm baby has a corrected age that

accounts for the weeks born earlier than 37 weeks.

Raising the Confidence of Mothers in Preterm Birth Care: Exploring the Secondary Role of the Internet

379

2.2- My preterm baby needs to visit his/her

doctor one to 2 weeks following discharge from the

NICU.

2.3- The mother’s milk is the recommended

feeding for preterm babies.

2.4- In case breast-feeding is not possible, the

preterm baby should be fed only formula milk for the

first 4 to 6 months.

2.5- The preterm baby should be fed at least

every three to four hours day and night.

2.6- Refrigerated milk must be placed on the

counter to warm to room temperature before being

given to the baby.

2.7- If the preterm baby is fed formula milk,

bottled water should be used to prepare the milk.

2.8- Adding more water to the bottle than

required might be dangerous to my preterm baby.

2.9- Extra milk that remains in the bottle can be

used for the next feed.

2.10-Prepared formula milk should be stored in

the refrigerator and used within 24-48 hours.

2.11-Milk bottles need to be cleaned with hot and

soapy water (or on the top rack of the dishwasher).

2.12-I know if my preterm baby is getting enough

breast milk or formula milk through the daily number

of wet.

2.13-Preterm babies do not need to be bathed

every day.

2.14-The preterm baby should be bathed either

before feeding or at least one hour after feeding.

2.15-A baby should always be transported in a

rear-facing infant-only car safety seat.

2.16-My preterm baby should have routine

monthly or bimonthly visits to the doctor up till the

age of 12 months.

2.17-My preterm baby needs to be assessed by a

pediatric neurologist.

2.18-My preterm baby may need neuro-

developmental therapy like physical therapy,

psychomotor therapy, feeding therapy...

2.19-My preterm baby may need eye

screening/exam

2.20-Rectal temperature 38ₒC or above is an

alarming sign of illness that requires doctor

consultation.

2.21-The decreased activity is an alarming sign of

illness that requires doctor’s consultation.

2.22-At 1 to 2 months, taking less than 6 feeds of

milk per day is an alarming sign that requires doctor’s

consultation.

2.23-The absence of wet diapers for more than 6

hours is an alarming sign that requires doctor’s

consultation.

2.24-Diarrhea (more stools than the baby’s usual)

for more than one day is an alarming sign that requires

doctor’s consultation.

2.25-Unusual (more than the usual spitting)

vomiting is an alarming sign that requires doctor’s

consultation.

2.26-Yellowish eyes or skin is an alarming sign

that requires doctor’s consultation.

2.27-Fast or difficult breathing is an alarming sign

that requires doctor’s consultation.

2.28-Common cold can cause severe respiratory

illness in preterm babies.

2.29-Preterm babies are vulnerable and more

prone to infections.

2.30-Preterm babies’ vaccination schedule is

different from that of term babies.

2.31-Crowded places and visits increase preterm

babies’ exposure to infections.

2.32-The number of people who provide

care/interact with my preterm baby at home should be

limited.

2.33- Baby should be placed on the back and not

on the stomach while sleeping to avoid the risk of

sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS)

2.34-I should log my baby’ (temperature, milk

intake, daily wet diaper…) to share with the doctor

during the follow-up visits.

2.35-Mother and father skin-to-skin contact with

the preterm baby is beneficial for the baby’s well-

being and development.

2.36-Play has an important role in the

development of my preterm baby.

2.37-Tummy time is essential for the baby’s

development, provided that it is supervised.

Section 2. NICU training and post-discharge

services (NICU_T1-T10 ): Possible answers: 1: Yes

2: No 3: Not Applicable .

NICU_T1: 1.1-I was given instructions about

caring for my preterm baby at home by the NICU

team before discharge.

NICU_T2: 1.2-The NICU staff taught me how to

hold my preterm baby

NICU_T3: 1.3-The NICU staff taught me how to

position (place) my preterm baby in bed.

NICU_T4: 1.4- The NICU staff prepared me to

interact with my preterm baby

NICU_T5: 1.5- The NICU staff taught me how to

feed my preterm baby

NICU_T6: 1.6- The NICU staff taught me how to

identify early signs of illness in my preterm baby

NICU_T7: 1.7- The NICU staff taught me how to

identify signs of discomfort (like colic pain, hunger,

diaper rash) in my preterm baby

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

380

NICU_T8: 1.8-The NICU team guided me to who

to call if I have questions after discharge

Section3. Source of Knowledge: Possible

answers: Never, 2: Rarely, 3: Sometimes, 4: Often, 5:

Always.

NICU_T9 3.1- I seek information on caring for

my preterm baby from the NICU nurses

NICU_T10 3.2- I seek information on caring

for my preterm baby from my baby’s doctor

ONLINE_1 3.3- I seek information on caring

for my preterm baby from official online

sources/websites like the World Health Organization

(WHO), Center for Disease Control (CDC), and other

scientific societies.

ONLINE_2 3.4- I seek information on caring

for my baby from online sources like Google and

other websites and mobile applications …

F&F 3.5- I seek information on caring for my

preterm baby from family and friends.

Section 4. Attitudes (Confidence) Possible

answers: 5 Point Likert Scale

Scale: 1: Strongly Disagree – 2: Disagree- 3:

Neither disagree nor agree - 4: Agree – 5: Strongly

Agree

CONF 4.1: 4.1- Given the information I received

from the NICU, I feel comfortable interacting with

my infant at home

CONF 4.2: 4.2- I understand the information that

healthcare professionals gave me about my baby’s

general health condition.

CONF 4.3: 4.3- I believe that the information and

instructions I received from the NICU are sufficient

for care for my preterm baby.

CONF 4.4 4.4- I believe I need additional

information to feel more comfortable

interacting/caring for my infant at home.

CONF 4.5 4.5- I am afraid to touch my baby

because I may hurt or upset the baby.

CONF 4.6 4.6- I am confident in my

understanding of my baby’s developmental

milestones.

CONF 4.7 4.7- I am confident that I know

the screening and follow-up assessments needed

following discharge.

CONF 4.8 4.8- I am confident that I know

about the early signs of illness when my baby needs

medical follow-up.

CONF 4.9 4.9- I am confident I know what

to do when I detect early signs of illness.

CONF 4.10 4.10- Overall, I am confident

handling and caring for my infant at home

Section 5. Technology Use. Possible answers:

Agree=1 Disagree=0

ICT_USE I use electronic platforms or mobile

applications to get information about caring for my

baby to help me care for my baby.

Section 6. External factors

AGE 6.1- Maternal age in years: ________

EDU 6.2- Highest education/degree: < Pre-

High School; High School+; Higher Education>

NICU_DAYS 6.4- How many days did your

preterm baby spend in the NICU? ------

1ST_PREG 6.5- Is this your first

pregnancy? 1: Yes – 2: No; if no, please go to

question 6.5.

Raising the Confidence of Mothers in Preterm Birth Care: Exploring the Secondary Role of the Internet

381