Electrical Properties of Filled PVA-C for Bioelectrical Impedance

Spectroscopy Phantoms

Anna Bublex, Amalric Montalibet, Bertrand Massot and Claudine Gehin

INSA Lyon, Ecole Centrale de Lyon, CNRS, Universite Claude Bernard Lyon 1,

CPE Lyon, INL, UMR5270, 69621 Villeurbanne, France

Keywords: PVA Phantom, Hydrogel, Bioelectrical Impedance Spectroscopy, Conductivity, Permittivity,

Living Tissue, Electrical Properties.

Abstract: This paper investigates the electrical properties of polyvinyl alcohol cryogel (PVA-C) filled with various

materials to develop biological phantoms for bioelectrical impedance spectroscopy (BIS) applications.

PVA-C is a hydrogel that undergoes cross-linking through freeze-thaw cycling, known for its long-term

stability and mechanical properties, which closely mimic those of living tissue, making it a superior alternative

to traditional gelling agents such as agar. To assess the impact of different fillers, samples with varying filler

proportions were prepared, and their electrical properties were analysed using BIS across a low-frequency

range (1 kHz to 1 MHz). The study was divided into two parts: the first one focused on the effects of PVA

concentration, the number of freeze-thaw cycles, molecular weight, and time-dependent behaviour on

PVA-C’s electrical properties. The second part compared the electrical properties of PVA-C combined with

various fillers, including particles, polymers, and ceramics. Finally, the results were compared with existing

published data on the electrical properties of living muscle and fat.

1 INTRODUCTION

Bioelectrical impedance spectroscopy (BIS) is a

valuable technique for assessing the composition,

structure, and functional properties of living tissues.

This is achieved by passing an alternating current

through a body part and measuring the resulting

voltage at low frequencies. To ensure the accuracy

and reliability of BIS sensors used in body

composition analysis, thorough validation is

essential. This involves conducting precise

measurements to compare the sensor outputs against

known standards or reference methods. However, the

inherent variability of human physiology poses

challenges to obtaining consistent in vivo data, as

short-term fluctuations within individuals

(intra-individual) and differences between

individuals (inter-individual) can influence results.

To address these challenges, researchers utilise

phantoms (artificial physical models) designed to

replicate the properties of biological tissues.

Phantoms provide a stable and repeatable

environment for testing and enable precise control

over tissue parameters during validation studies.

Phantoms have been extensively developed using

biological materials such as vegetable-based

substances or gelling agents filled with conductive

particles (Anand et al., 2019; Hess et al., 2022;

Mobashsher & Abbosh, 2014). While these materials

effectively replicate the electrical properties of living

tissues, they often suffer from short-term stability and

inadequate mechanical strength. To overcome these

limitations, researchers have explored alternative

materials such as silicones, elastomers, and filled

polymers (Dunne et al., 2018; Goyal et al., 2022).

Among these polymers, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) has

attracted significant research interest. PVA is soluble

in hot water and can be cross-linked through

freeze-thaw cycles to form polyvinyl alcohol cryogel

(PVA-C), a hydrogel with mechanical properties and

texture similar to those of human tissue (Chen et al.,

2012; Goyal et al., 2022). While PVA-C exhibits

excellent mechanical properties, its electrical

properties are not inherently comparable to those of

living tissue. To address this, fillers are incorporated

into the hydrogel to achieve appropriate conductivity.

This paper investigates the electrical properties of

PVA-C samples loaded with various fillers.

Conductivity and permittivity measurements were

26

Bublex, A., Montalibet, A., Massot, B. and Gehin, C.

Electrical Properties of Filled PVA-C for Bioelectrical Impedance Spectroscopy Phantoms.

DOI: 10.5220/0013103800003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 1, pages 26-34

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

performed to evaluate their potential application in

the development of electrical phantoms.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Materials

The materials used in this study are summarised in

Table 1.

Table 1: Materials used in this study.

Material Descri

p

tion Su

pp

lier

PVA

145 kDa

Fully hydrolysed Sigma-Aldrich

PVA

60 kDa

Fully hydrolysed Sigma-Aldrich

Li

g

nin Alkali Si

g

ma-Aldrich

1,2-propanediol

ACS reagent,

≥99.5%

Sigma-Aldrich

Barium titanate

Powder, <3 µm,

99%,

M=233.19 g/mol

Sigma-Aldrich

Agar

Industrial agar,

CONDALAB

Dutscher

NaCl

M=58.44 g/mol,

APPLICHEM

Dutscher

Graphite

Purity 99.9%,

particle size

5-10

µ

m

NanoGrafi

Plaste

r

Parexlanko Local market

Glycerine Coope

r

Local market

Corn flou

r

Maïzena Local market

“Sommières” earth

‘’La fée du logis

vert’’

Local market

Diatomaceous earth Novatera Local market

Glass beads

5-20 µm and

150-200 µm

Local market

2.2 PVA-Cryogel: A Brief Overview

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) is a versatile synthetic

polymer widely used in medical applications such as

cartilage replacement and the fabrication of

cardiovascular devices (Kobayashi & Hyu, 2010;

Wan et al., 2014). Its ability to form stable hydrogels

through freeze-thaw cross-linking has made it a

material of significant interest for tissue engineering

and biomedical research. This process results in the

formation of polyvinyl alcohol cryogel (PVA-C),

which closely mimics the texture and mechanical

properties of human tissues, as confirmed in multiple

studies (Chen et al., 2012; Duboeuf et al., 2009;

Fromageau et al., 2007; Gautam et al., 2021; Goyal

et al., 2022; Khaled et al., 2007).

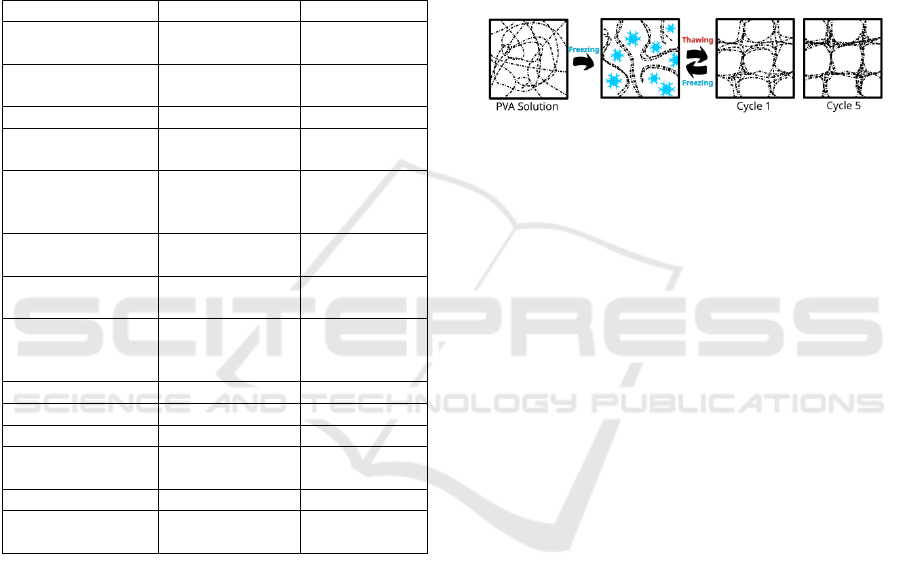

The process of crosslinking PVA to form PVA-C

is illustrated in Figure 1. During the freezing process,

the formation of ice crystals forces the PVA chains

into a more compact configuration, resulting in the

creation of a PVA-rich phase. The PVA regions

become increasingly concentrated, and the formation

of hydrogel bonds is facilitated by an increase in the

number of freeze-thaw cycles. Given the slow

movement of macromolecules, multiple cycles are

required to achieve a robust hydrogel. The strength of

the resulting hydrogel also depends on the molecular

weight and concentration of PVA in solution (Adelnia

et al., 2022; Wan et al., 2014).

Figure 1: Effect of cycling on the microstructure of PVA-C.

The mechanical and electrical properties of

PVA-C are influenced by several factors, including

the degree of hydrolysis, molecular weight,

concentration, and the freeze-thaw process. These

properties change during the course of the cycles

(Adelnia et al., 2022; Getangama et al., 2020; Wan et

al., 2014). Notably, below a concentration of 5% w/w

of PVA, the hydrogel will not form. Furthermore, the

mechanical strength of the hydrogel significantly

decreases when the concentration is below 10% w/w,

whereas concentrations above 30% w/w make the

mixture difficult to manipulate (Adelnia et al., 2022).

The long-term stability of PVA-C is particularly

noteworthy, making it a preferred option over

traditional gelling agents such as agar or gelatine

(Hess et al., 2022). Additionally, PVA is considered

an environmentally friendly material due to its

biocompatibility, biodegradability, and non-toxicity

during both the manufacturing and cross-linking

processes (Belay, 2023).

2.3 Preparation of the Samples

This paper presents an analysis of two distinct sample

types. Both sample types were placed in a standard

measuring cell (refer to section 2.4.2) to compare the

conductivity and permittivity values of the materials

with those of muscle reported in the literature.

The first set of samples enables the investigation

of the electrical properties of PVA-C based on

various parameters, including the PVA concentration

in solution, the number of freeze-thaw cycles, the

molecular weight of PVA and the evolution of

Electrical Properties of Filled PVA-C for Bioelectrical Impedance Spectroscopy Phantoms

27

PVA-C properties over time. This investigation was

conducted on three distinct samples.

The first PVA-C sample was cross-linked from a

10% w/w PVA solution and underwent a single

freeze-thaw cycle. The remaining two samples were

of considerable size, from which smaller sub-samples

were extracted for bioimpedance measurements

across varying cycles. One sub-sample was

specifically examined to assess its stability over time.

During the intervals between measurements, the

sample was stored in a plastic film at room

temperature. In the case of the 60 kDa sample, the

first freeze-thaw cycle resulted in the formation of a

hydrogel that lacked the required robustness for

handling and measurement. Table 2 summarises the

characteristics of the studied PVA-C samples. In this

study, weight proportions (% w/w) are expressed in

relation to the weight of the material relative to the

weight of the solvent (deionised water).

Table 2: Summary of characteristics for the studied PVA-C

samples.

Molecular

weight

Cycle

Concentration

(% w/w)

Study

of

stabilit

y

1

145 kDa

1

10

2

15

x

2 15

3 15

4 15

3 60 kDa

2 15

3 15

4 15

The second set of samples was prepared to

investigate the electrical properties of PVA-C filled

with different types of particles, polymers, and other

materials. The objective was to examine the effect of

varying the proportions of fillers in a solution of

PVA, with a molecular weight of 145 kDa and a

concentration of 10% w/w, on its electrical

properties. All samples were subjected to a single

freeze-thaw cycle.

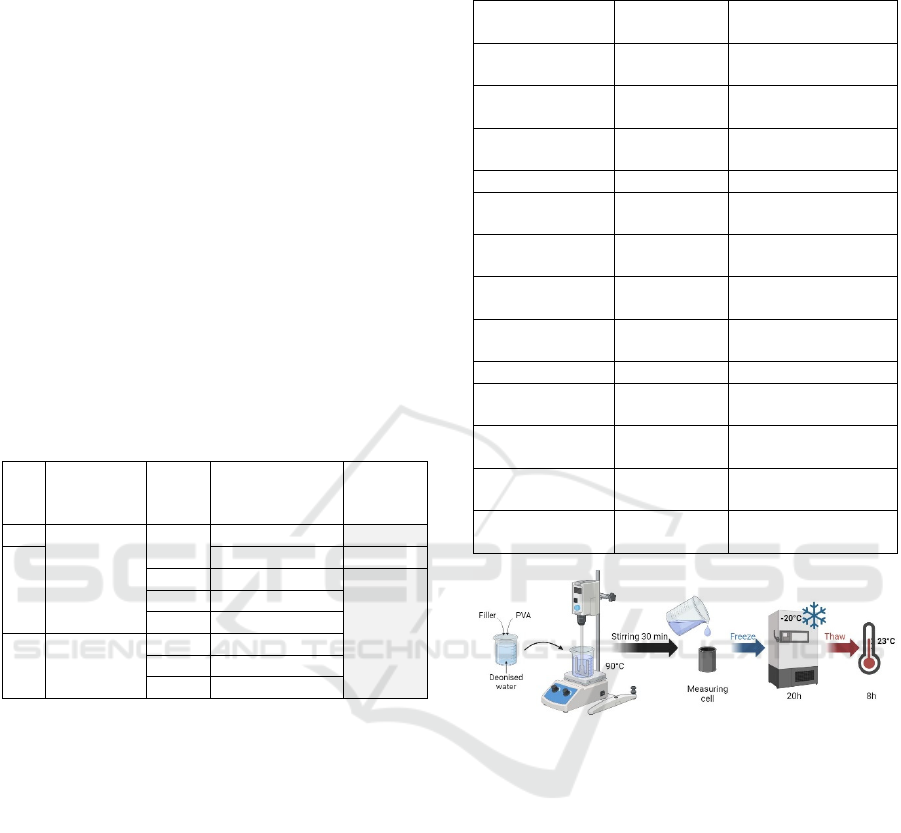

Samples were prepared according to the material

proportions detailed in Table 3.

For each sample, the materials were mixed with

deionised water in a beaker and mechanically agitated

for 30 minutes at 90°C. The resulting mixture was

then transferred into the standard measuring cell for a

single freeze-thaw cycle, consisting of freezing

at -20°C for 20 hours, followed by thawing at room

temperature (23°C) for 8 hours (see Figure 2).

Table 3: Summary of sample composition based on PVA

(145 kDa, 10% w/w, one freeze-thaw cycle).

Materials

Proportions

(% w/w)

Remarks

Lignin

1-5-10-

20% w/w

-

1,2-propanediol

5-10-

20% w/w

Also known as

p

ro

py

lene

g

l

y

col

Barium titanate 5-15% w/w

Must be handled

with

p

rotection

A

g

a

r

1-2-3% w/w Gellin

g

a

g

ent

NaCl

0.1-0.5-

1% w/w

Enhance ionic

conductivit

y

Graphite

0.1-0.5-1-2-

5% w/w

Plaster

0.1-0.5-2-5-

10% w/w

Glycerine 1-2-5% w/w

Also known as

g

l

y

cerol

Corn flou

r

1-2-5% w/w

“Sommières”

earth

2-5-10-

20% w/w

Clay known for its

absorbent properties

Diatomaceous

earth

2-5-10-

20% w/w

Fossilized remains

of diatoms (algae)

Glass beads

5-20

µ

m

2-5-10-

20% w/w

Glass beads

150-200

µ

m

2-5-10-

20% w/w

Figure 2: Sample preparation steps. Created in BioRender.

Bublex, A. (2025) https://BioRender.com/u47q709.

2.4 Impedance Spectroscopy

Measurement

2.4.1 Bioelectrical Impedance Spectroscopy

Bioelectrical impedance spectroscopy (BIS) is a

non-invasive technology used to measure the

volumes of various body compartments, including

total body water and extracellular water. BIS

measures impedance at multiple frequencies to

analyse cellular membrane integrity and fluid

distribution, thereby offering insights into cellular

health and hydration status. Impedance, a

generalisation of Ohm's law to alternating current, is

a complex quantity and is expressed as: (Bera, 2014;

Grimnes & Martinsen, 2015)

BIODEVICES 2025 - 18th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

28

𝑍 𝑅 𝑗𝑋 (1)

where 𝑍: impedance

𝑅: resistance

𝑋: reactance

2.4.2 Measurement Tools

In this study, the Multifrequency Impedance

Analyzer (MFIA 5 MHz model) from Zurich

Instrument served as the reference standard for

bioimpedance measurements. The device is capable

of performing bioimpedance measurements across a

frequency range of 1 mHz to 5 MHz and within a

measurement range of 1 mΩ to 1 TΩ. In the present

investigation, measurements were conducted over a

frequency range of 1 kHz to 1 MHz, with 100 data

points acquired at logarithmic intervals. Standard

measuring cells were developed based on the model

established by Suga (Suga et al., 2013). The cells

consist of transparent, extruded polycarbonate

cylinders with a length of 50 mm and an inner

diameter of 24 mm. Measurements were performed

using these standard measuring cells, as illustrated in

Figure 3.

Figure 3: Schematic of a standard measuring cell. Length

d = 50 mm, inner surface area A = 4.52 cm².

The electrodes were 30 mm diameter, gold-plated

discs, manufactured by JLCPCB, China. The gold

coating was specified as ENIG 2U (Electroless Nickel

Immersion Gold) with a thickness of 2 µm. The

support structure was designed using Autodesk

Fusion 360 and 3D printed using polylactic acid

(PLA). A spring mechanism was incorporated into

the design to ensure a constant force applied to the

sample.

2.4.3 Two-Electrode Measurements: Model

Extraction of Conductivity and

Permittivity

The conductivity and relative permittivity of a sample

were evaluated through impedance measurements

conducted in a controlled geometry. These data were

compared with existing literature values for living

tissue (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Electrical properties of 4 living tissue - Adapted

from Gabriel et al. 1996 (Gabriel, 1996).

To extract the values of conductivity (σ) and

relative permittivity (ε

r

) from bioimpedance

measurements (Z), admittance ( Y ) was calculated

according to the methodology proposed by A. Ivorra

(A.Ivorra, 2002):

𝑌

1

𝑍

and 𝑌𝐺𝑖𝐵 (2)

where G is conductance and B is susceptance. The

values of conductivity and relative permittivity are

expressed as follows:

𝜎

𝐺

𝐾

and 𝜀

𝐵

𝐾2𝜋𝑓𝜀

(3)

with the cell coefficient 𝐾𝐴/𝑑, 𝐴 is the cross-

sectional area and 𝑑 is the cylinder length (see Figure

3). In this document, the term “relative permittivity”

will be used interchangeably with “permittivity”.

3 RESULTS

3.1 PVA-C Electrical Properties as a

Function of Number of Cycles and

Molecular Weight

The evolution of the electrical properties of two

PVA-C samples with different molecular weights

over multiple cycles is shown in Figure 5. In the case

of the 60 kDa sample, the first cycle produced a

hydrogel that lacked sufficient robustness for

handling and measurement.

Figure 5: Electrical properties of PVA-C samples over

multiple cycles.

Electrical Properties of Filled PVA-C for Bioelectrical Impedance Spectroscopy Phantoms

29

The molecular weight significantly influences the

conductivity of the samples and the permittivity at

low frequencies. Conductivity increases with the

number of freeze-thaw cycles, but higher molecular

weight correlates with lower conductivity. For both

PVA-C samples, permittivity tends to converge at

high frequencies.

3.2 PVA-C Electrical Properties as a

Function of Concentration

Figure 6 illustrates the electrical properties of two

PVA-C samples with varying concentrations of PVA

in solution.

Figure 6: Electrical properties of PVA-C samples with

different concentrations of PVA – 10% w/w and 15% w/w.

As the concentration of PVA in solution

increases, both conductivity and permittivity show a

corresponding rise for samples of a given molecular

weight.

3.3 PVA-C Electrical Properties over

Time

Figure 7 illustrates the stability of the electrical

properties of a PVA-C sample stored in a plastic film

at room temperature over a four-day period.

Figure 7: Electrical properties of PVA-C over time.

Both conductivity and permittivity show a notable

daily increase. This increase is likely due to water loss

from samples that are not completely hermetically

sealed.

3.4 Hydrogel Based on Filled PVA-C

This section examines the impact of varying the

proportion of fillers in a solution of PVA, with a

molecular weight of 145 kDa and a concentration of

10% w/w, on the electrical properties. All samples

were subjected to a single freeze-thaw cycle.

3.4.1 Agar

The comparative electrical properties of PVA-C filled

with different proportions of agar, along with a pure

PVA-C sample, are presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Electrical properties of PVA-C filled with various

proportions of agar.

The addition of agar increases both conductivity

and permittivity, aligning with its ionic nature, which

enhances ion mobility within the hydrogel matrix.

This behaviour suggests that agar is a promising

candidate for mimicking the electrical properties of

biological tissues.

3.4.2 Corn Flour

Figure 9 illustrates the comparative electrical

properties of PVA-C filled with varying proportions

of corn flour, alongside a pure PVA-C sample.

Figure 9: Electrical properties of PVA-C filled with various

proportions of corn flour.

The addition of corn flour reduces conductivity

without significantly affecting permittivity,

suggesting that its primary effect is to obstruct ion

flow rather than alter dielectric properties. This

characteristic makes it suitable for applications where

reduced conductivity is desired.

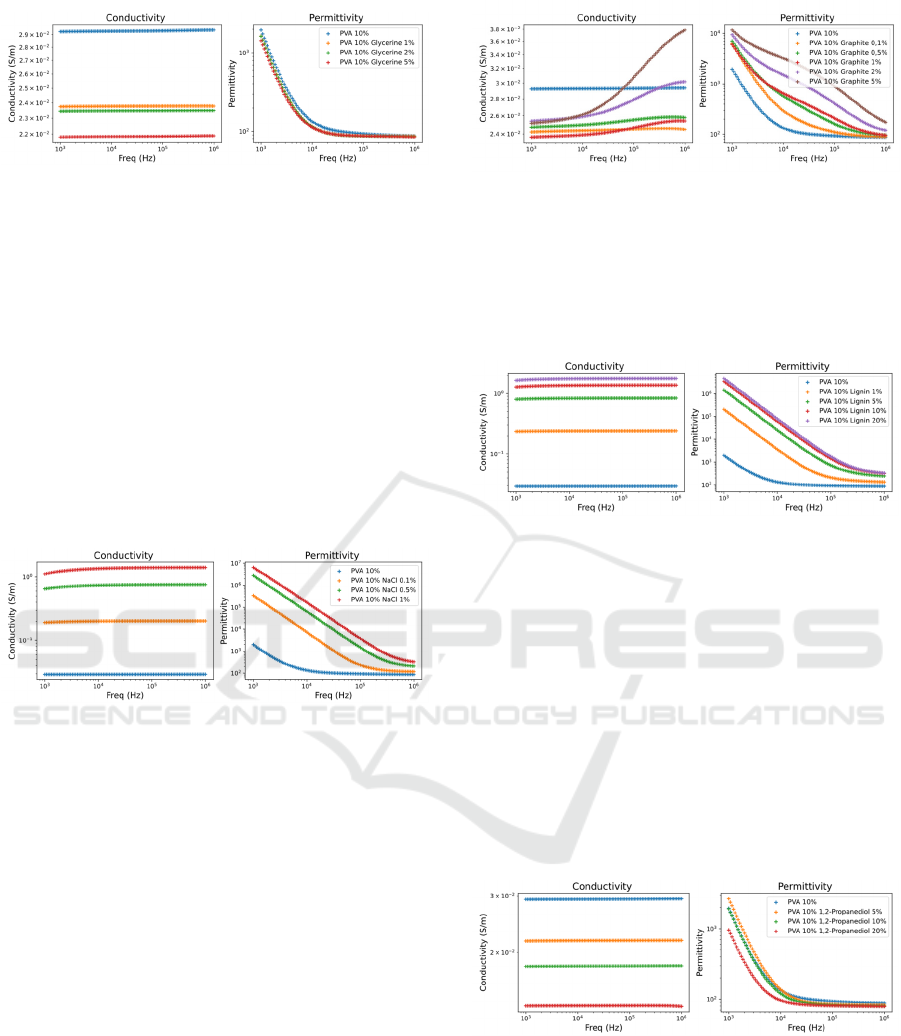

3.4.3 Glycerine

Figure 10 shows the electrical properties of PVA-C

filled with various amounts of glycerine, compared to

a pure PVA-C sample.

BIODEVICES 2025 - 18th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

30

Figure 10: Electrical properties of PVA-C filled with

various proportions of glycerine.

Glycerine notably decreases conductivity while

leaving permittivity relatively unchanged. This may

be due to its insulating properties and ability to reduce

free ion concentration. Its inclusion could be

beneficial for simulating tissues with low

conductivity, but it may require reinforcement to

maintain mechanical strength.

3.4.4 NaCl

Figure 11 illustrates the comparative electrical

properties of PVA-C filled with varying proportions

of NaCl, compared to a pure PVA-C sample.

Figure 11: Electrical properties of PVA-C filled with

various proportions of NaCl.

NaCl significantly increases both conductivity

and permittivity, consistent with its role as an ionic

conductor. This makes it highly effective for

muscle-mimicking phantoms. The observed linear

relationship between NaCl concentration and

conductivity supports its controlled application.

3.4.5 Graphite

The comparative electrical properties of PVA-C filled

with different proportions of graphite, compared to a

pure PVA-C sample, are presented in Figure 12.

The conductivity and permittivity curves exhibit

significant changes. When the graphite proportion is

less than 1%, conductivity remains lower than that of

the pure PVA-C sample. In contrast, for proportions

above 2%, the conductivity curve increases beyond

that of PVA-C alone at higher frequencies. The

permittivity curve is primarily affected at

concentrations above 0.5%.

Figure 12: Electrical properties of PVA-C filled with

various proportions of graphite.

3.4.6 Lignin

Figure 13 illustrates the comparative electrical

properties of PVA-C filled with varying proportions

of lignin, compared to a pure PVA-C sample.

Figure 13: Electrical properties of PVA-C filled with

various proportions of lignin.

The incorporation of lignin into the hydrogel

leads to a notable enhancement in both conductivity

and permittivity, reaching levels comparable to those

observed with NaCl. The electrical properties show a

rapid increase at low lignin concentrations and appear

to plateau at concentrations above 10% lignin.

3.4.7 1,2-Propanediol

Figure 14 shows the electrical properties of PVA-C

filled with various amounts of 1,2-propanediol,

compared to a pure PVA-C sample.

Figure 14: Electrical properties of PVA-C filled with

various proportions of 1,2-propanediol.

The reduction in both conductivity and

permittivity suggests its use as a dielectric filler for

applications requiring a low electrical response.

However, its concentration must be carefully

controlled to prevent adverse effects on mechanical

properties.

Electrical Properties of Filled PVA-C for Bioelectrical Impedance Spectroscopy Phantoms

31

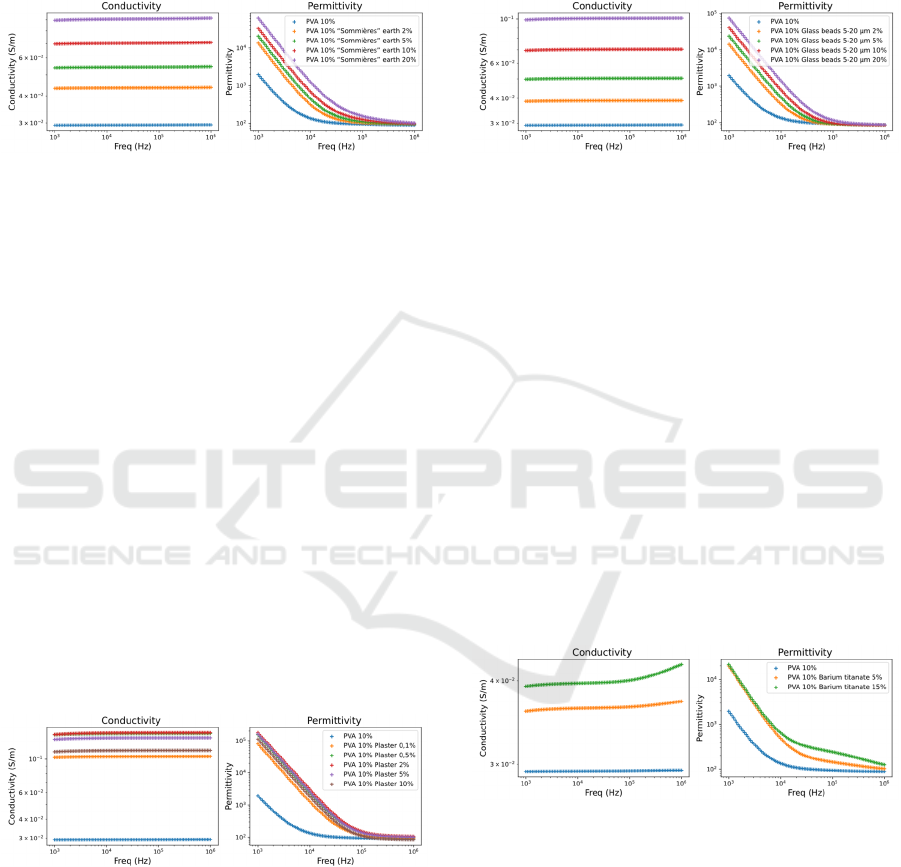

3.4.8 “Sommières” Earth

The comparative electrical properties of PVA-C filled

with different proportions of “Sommières” earth,

compared to a pure PVA-C sample, are presented in

Figure 15.

Figure 15: Electrical properties of PVA-C filled with

various proportions of “Sommières” earth.

The addition of “Sommières” resulted in a

moderate enhancement in conductivity and

permittivity relative to NaCl or lignin. This

improvement is likely due to its high surface area and

ionic exchange capacity. Its effect on mechanical

properties should be further explored to determine its

practical applicability.

3.4.9 Diatomaceous Earth

Diatomaceous earth is too dense to remain suspended

in the PVA mixture during freezing, causing it to

settle at the bottom of the sample due to gravity. As a

result, the samples exhibit inhomogeneity, and their

electrical properties have not been characterised.

3.4.10 Plaster

Figure 16 shows the electrical properties of PVA-C

filled with various amounts of plaster, compared to a

pure PVA-C sample.

Figure 16: Electrical properties of PVA-C filled with

various proportions of plaster.

Plaster exhibited a marked increase in both

conductivity and permittivity. Its ease of handling and

low cost make it a strong candidate for large-scale

phantom development.

3.4.11 5-20 µm Glass Beads

The comparative electrical properties of PVA-C filled

with different proportions of 5-20 µM glass beads,

compared to a pure PVA-C sample, are presented in

Figure 17.

Figure 17: Electrical properties of PVA-C filled with

various proportions of 5-20 µm glass beads.

The incorporation of glass beads into the hydrogel

matrix results in a significant increase in both

electrical conductivity and permittivity.

3.4.12 Glass Beads 150-200 µm

The 150-200 µM glass beads are too dense for the

viscosity of the PVA mixture, causing them to settle

at the bottom of the sample due to gravity. As a result,

the samples lack homogeneity, and their electrical

properties have not been measured.

3.4.13 Barium Titanate

Figure 18 illustrates the comparative electrical

properties of PVA-C filled with varying proportions

of barium titanate, compared to a pure PVA-C

sample.

Figure 18: Electrical properties of PVA-C filled with

various proportions of barium titanate.

The incorporation of barium titanate into the

hydrogel resulted in an increase in both electrical

conductivity and permittivity. The addition of 15%

barium titanate led to a significant increase in

permittivity, with a notable rise observed in the

frequency range 10

4

to 10

6

Hz compared to the 5%

barium titanate sample. The significant enhancement

in permittivity at higher concentrations highlights

barium titanate's suitability for applications requiring

high dielectric constants.

BIODEVICES 2025 - 18th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

32

3.5 Comparison with Literature Data

A comparative graph of the conductivity and

permittivity of the samples is presented in Figure 19,

alongside literature data from living muscle and fat

tissue for reference.

Figure 19: Electrical properties of samples compared with

literature data for muscle and fat tissue.

The comparison with literature data confirms the

effectiveness of the fillers in replicating the electrical

properties of muscle and fat. For instance, NaCl and

lignin closely mimic the high conductivity and

permittivity of muscle tissue, while agar and glass

beads align more closely with the lower values typical

of fat tissue. The study highlights the importance of

selecting appropriate filler combinations to fine-tune

phantoms for specific tissues.

4 DISCUSSION

The influence of fillers on the electrical properties of

PVA-C hydrogel are summarised in Table 4.

Table 4: Summary of the principal effects of fillers on the

electrical properties of PVA-C hydrogel.

Increase in both conductivity

and permittivity

Agar, NaCl, lignin,

“Sommières” earth,

plaster, glass beads,

b

arium titanate

Decrease in both conductivity

and

p

ermittivit

y

1,2-propanediol

Decrease in conductivity

Corn flour,

glycerine

Change in conductivity and

increase in

p

ermittivit

y

Graphite

It is observed that certain fillers are more effective

in modifying the electrical properties of hydrogels.

Depending on the objectives of the developed

phantom, a combination of different fillers can be

used to efficiently mimic the electrical properties of

living tissues (see Figure 19). In previous works, the

authors developed a muscle phantom by

incorporating fillers such as agar, graphite, and NaCl

into a PVA-C matrix. This formulation was

specifically designed to mimic the electrical

properties of living muscle tissue while exhibiting

excellent mechanical properties. As a result, it

provides a reliable model for bioimpedance studies

(Bublex et al., 2024).

The measurements performed on all samples

demonstrated a plateau in permittivity at high

frequencies (1 MHz). This plateau correlates with the

relative permittivity of water (ε

r

= 80), which can be

attributed to the water-based composition of the

samples. This behaviour is consistent with the

expected properties of hydrogels and confirms the

significant influence of water content on their

electrical response.

PVA-C-based phantoms are predominantly

investigated for their mechanical properties.

However, it is essential to recognise that the

incorporation of any filler inevitably impacts the

hydrogel’s mechanical properties. For instance, while

1,2-propanediol effectively reduce conductivity,

concentrations exceeding 10% result in a notable

decline in mechanical strength, rendering the

hydrogel difficult to handle.

The study of PVA-C revealed shrinkage and

alterations in mechanical properties across

freeze-thaw cycles. Further investigations are needed

to assess these properties. Additionally, storage

remains a significant concern; plastic film is not a

viable option for maintaining electrical properties

over an extended period. Vacuum packing should be

investigated to prevent water loss.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study comprehensively examined the impact of

various fillers on the electrical properties of PVA-C

hydrogels to enhance their suitability for

bioimpedance spectroscopy (BIS) applications.

Through systematic experimentation, the effects of

fillers on electrical conductivity and permittivity were

quantified and compared with the electrical properties

of living tissues such as muscle and fat.

The results underscore the potential of specific

fillers, such as NaCl and lignin, to closely mimic the

electrical properties of muscle, while other fillers, like

agar and glass beads, show promise for developing fat

phantoms.

Furthermore, the study revealed that while fillers

are essential for achieving the desired electrical

characteristics, their incorporation also affects the

mechanical properties of the hydrogel. This

highlights the importance of optimizing filler

Electrical Properties of Filled PVA-C for Bioelectrical Impedance Spectroscopy Phantoms

33

composition to balance both electrical and

mechanical performance. The observed correlation

between water content and permittivity emphasizes

the need for improved storage solutions, such as

vacuum packing, to maintain the long-term stability

of electrical properties.

In conclusion, the findings of this research

provide a robust foundation for developing advanced

PVA-C-based electrical phantoms, offering reliable

and stable alternatives for BIS studies and other

biomedical applications.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is part of the Symphonies project,

receiving funding from BPI France for the France

2030 program, supported by the French government.

REFERENCES

Adelnia, H., Ensandoost, R., Shebbrin Moonshi, S., Gavgani,

J. N., Vasafi, E. I., & Ta, H. T. (2022). Freeze/thawed

polyvinyl alcohol hydrogels : Present, past and future.

European Polymer Journal, 164, 110974.

A.Ivorra. (2002). Bioimpedance Monitoring for

physicians : An overview.

Anand, G., Lowe, A., & Al-Jumaily, A. (2019). Tissue

phantoms to mimic the dielectric properties of human

forearm section for multi-frequency bioimpedance

analysis at low frequencies. Materials Science and

Engineering: C, 96, 496‑508.

Belay, M. (2023). Review on Physicochemical Modification

of Biodegradable Plastic : Focus on Agar and

Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA). Advances in Materials

Science and Engineering, 2023, 1‑11.

Bera, T. K. (2014). Bioelectrical Impedance Methods for

Noninvasive Health Monitoring : A Review. Journal of

Medical Engineering, 2014, 1‑28.

Bublex, A., Montalibet, A., Massot, B., & Gehin, C. (2024).

Eco-Friendly Bioimpedance Muscle Phantom : PVA-

Agar Hydrogel Mimicking Living Tissue at Low

Frequencies. 2024 46th Annual International

Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and

Biology Society (EMBC), Orlando, Florida.

Chen, S. J.-S., Hellier, P., Marchal, M., Gauvrit, J.-Y.,

Carpentier, R., Morandi, X., & Collins, D. L. (2012).

An anthropomorphic polyvinyl alcohol brain phantom

based on Colin27 for use in multimodal imaging.

Medical Physics, 39(1), 554‑561.

Duboeuf, F., Basarab, A., Liebgott, H., Brusseau, E.,

Delachartre, P., & Vray, D. (2009). Investigation of

PVA cryogel Young’s modulus stability with time,

controlled by a simple reliable technique. Medical

Physics, 36(2), 656‑661.

Dunne, E., McGinley, B., O’Halloran, M., & Porter, E.

(2018). A realistic pelvic phantom for electrical

impedance measurement. Physiological Measurement,

39(3), 034001.

Fromageau, J., Gennisson, J.-L., Schmitt, C., Maurice, R.

L., Mongrain, R., & Cloutier, G. (2007). Estimation of

polyvinyl alcohol cryogel mechanical properties with

four ultrasound elastography methods and comparison

with gold standard testings. IEEE Transactions on

Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics and Frequency Control,

54(3), 498‑509.

Gabriel, C. (1996). Compilation of the Dielectric Properties

of Body Tissues at RF and Microwave Frequencies.:

Defense Technical Information Center.

Gautam, U. C., Pydi, Y. S., Selladurai, S., Das, C. J., Thittai,

A. K., Roy, S., & Datla, N. V. (2021). A Poly-vinyl

Alcohol (PVA)-based phantom and training tool for use

in simulated Transrectal Ultrasound (TRUS) guided

prostate needle biopsy procedures. Medical

Engineering & Physics, 96, 46‑52.

Getangama, N. N., de Bruyn, J. R., & Hutter, J. L. (2020).

Dielectric properties of PVA cryogels prepared by

freeze–thaw cycling. The Journal of Chemical Physics,

153(4), 044901.

Goyal, K., Borkholder, D. A., & Day, S. W. (2022). A

biomimetic skin phantom for characterizing wearable

electrodes in the low-frequency regime. Sensors and

Actuators A: Physical, 340, 113513.

Grimnes, S., & Martinsen, O. (2015). Bioimpedance and

bioelectricity basics. Academic Press.

Hess, A., Liu, J., & Pott, P. P. (2022). Analysis of Dielectric

Properties of Gelatin-based Tissue Phantoms. Current

Directions in Biomedical Engineering, 8(2), 340‑343.

Khaled, W., Neumann, T., Ermert, H., Reichling, S.,

Arnold, A., & Bruhns, O. T. (2007). P1C-1 Evaluation

of Material Parameters of PVA Phantoms for

Reconstructive Ultrasound Elastography. 2007 IEEE

Ultrasonics Symposium Proceedings, 1329‑1332.

Kobayashi, M., & Hyu, H. S. (2010). Development and

Evaluation of Polyvinyl Alcohol-Hydrogels as an

Artificial Atrticular Cartilage for Orthopedic Implants.

Materials, 3(4), 2753‑2771.

Mobashsher, A. T., & Abbosh, A. M. (2014). Three-

Dimensional Human Head Phantom With Realistic

Electrical Properties and Anatomy. IEEE Antennas and

Wireless Propagation Letters, 13, 1401‑1404.

Suga, R., Inoue, M., Saito, K., Takahashi, M., & Ito, K.

(2013). Development of multi-layered biological tissue-

equivalent phantom for HF band. IEICE

Communications Express, 2(12), 507‑511.

Wan, W., Bannerman, A. D., Yang, L., & Mak, H. (2014).

Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) Cryogels for Biomedical

Applications. In O. Okay (Éd.), Polymeric Cryogels

(Vol. 263, p. 283‑321). Springer International

Publishing.

BIODEVICES 2025 - 18th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

34