Simulation and Evaluation of Thermal Effects Under MRI for

Cochlear Implants

Yuanling Ma

1

, Dian Yang

2

, Liping Qin

3

, Xuesong Ye

4a

and Congcong Zhou

5b

1

Biosensor National Special Laboratory, Key Laboratory of Biomedical Engineering of Ministry of Education,

College of Biomedical Engineering and Instrument Science, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, 310027, China

2

Zhe Jiang Key Laboratory of Intelligent Rehabilitation and Translational Neuroelectronics, China

3

Zhejiang Institute of Medical Device Supervision and Testing, China

4

National Engineering Research Center for Innovation And Application of Minimally Invasive Instruments,

College of Biomedical Engineering and Instrument Science, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, 310027, China

5

National Engineering Research Center for Innovation And Application of Minimally Invasive Instruments

,

Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, China

Keywords: RF-Induced Heating, Finite Element Method, Cochlear, Electromagnetic Safety.

Abstract: Cochlear implantation is a widely used rehabilitation method for severe sensorineural deafness, but MRI scans

can induce RF heating in implants, posing safety risks to patients. In this study, a novel finite-element-based

electromagnetic and thermal coupled simulation method to obtain the temperature distribution and maximum

temperature rise due to RF-induced heating is studied. This method allows for a quick analysis of the worst-

case implant configurations and an evaluation of RF heating effects. Additionally, for cochlear implants, we

propose a refined model parameters setting method which using a localized cochlear phantom in simulations

to analyse key factors affecting RF-induced heating include electrode length, lead trajectory, and phantom

model. In this paper, RF heating was evaluated using two phantoms, three electrode lengths, and three typical

lead trajectories, with the highest temperature rise observed at 1.922°C in the cochlear phantom. The results

show that small variations in electrode length have less impact compared to wire trajectory and phantom

model, indicating the need for greater focus on these factors when assessing RF heating in active implants.

1 INTRODUCTION

Deafness is one of the most prevalent disabling

conditions worldwide. The World Health

Organization (WHO) estimates that hearing

impairment costs the global economy approximately

$750 billion annually. Among the primary causes of

deafness is severe to profound hearing impairment,

which leads to disabling hearing loss (Chadha et al.,

2021). For patients with severe or profound

sensorineural deafness, cochlear implantation

remains the only effective method of

rehabilitation(Buchman et al., 2020). The increasing

necessity for MRI in cochlear implant users demands

rigorous safety assessments(Alberalar et al., 2023),

with RF-induced heating being a pivotal area of

focus.

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3439-3733

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8397-1491

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a widely

used diagnostic tool in clinical practice due to its

numerous advantages. It is non-invasive, free of

ionizing radiation, and can visualize internal

structures like the heart and blood vessels without the

use of contrast agents. MRI also offers high-

resolution imaging of soft tissues, minimal

interference from bone artifacts, and multidirectional

and multiparametric imaging capabilities(Koptyug et

al., 2023). However, the increasing strength of MRI

magnetic fields, combined with the advancement of

new MRI technologies, has raised concerns regarding

the biological effects and safety of MRI, particularly

for patients with medical implants. The high-power

radiofrequency (RF) coils used in MRI systems can

induce electromagnetic resonance in conductive

implants, leading to RF-induced heating, which may

Ma, Y., Yang, D., Qin, L., Ye, X. and Zhou, C.

Simulation and Evaluation of Thermal Effects Under MRI for Cochlear Implants.

DOI: 10.5220/0013113400003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 1, pages 119-125

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

119

cause irreversible tissue damage, such as burns. This

is especially concerning for patients with implants

located near sensitive areas, like the brain(Rezai et al.,

2002). Cochlear implants, positioned subcutaneously

behind the ear and close to the brain, are particularly

susceptible to this risk, making RF-induced heating a

critical safety issue that requires thorough testing.

Previous studies primarily focused on in vivo

testing, a method involving the implantation of

devices into animals or human subjects, followed by

the monitoring of physiological parameters in an MRI

environment. Crane et al. conducted a retrospective

analysis of the safety and diagnostic validity of

cochlear implants in patients undergoing MRI

scans(Crane et al., 2010). However, their study was

limited by the absence of quantitative measurements

and a lengthy experimental timeline. Additionally,

Luechinger et al. evaluated the RF safety of cochlear

implants in experimental pigs (Long White breed),

while Roger et al. assessed the radiofrequency safety

of pacemaker leads in Danish Long White

pigs(Luechinger et al., 2005). Despite these efforts,

the in vivo approach was constrained by the

limitations of measuring locations and difficulties in

obtaining precise data.

To ensure standardization, avoid potential

medical ethical issues, and improve experimental

convenience, the ASTM F2182 standard outlines a

test procedure in which the implant is embedded in a

gelatinized saline-filled body phantom, exposed to an

RF field with a whole-body average specific

absorption rate (SAR) of 2 W/kg using a benchtop

system. The temperature is monitored for 15 minutes,

and the local SAR is determined using a calorimetric

method(ASTM_International, 2019). Yang et al.

found that, for devices implanted in or near bone

tissue, the assessment of RF-EMF energy deposition

using an ASTM model that incorporates bone

provided a better correlation with human models

compared to the standard ASTM model(Yang et al.,

2024). However, despite the widespread use and

study of in vitro body models for RF heating

evaluations, significant limitations remain. The

human body is a complex, heterogeneous

environment composed of various tissues, and the

homogeneous gel-saline models used cannot

sufficiently mimic the diverse properties of human

tissues to accurately reflect the heating effects of

implants in such a complex biological

environment(Ran et al., 2017).

The ISO/TS 10974:2018 standard outlines a four-

layer test methodology designed to account for the

wide range of configurations and applications of

active implantable medical devices (AIMDs), aiming

to provide a conservative estimate of energy

deposition in controlled in vitro test systems

(Standardization, 2018). Numerous studies have also

employed the Finite-Difference Time-Domain

(FDTD) method and transfer function approach to

assess RF-induced heating. For example, Zeng et al.

evaluated RF heating in a cochlear implant within a

1.5T MRI coil using the FDTD method, alongside a

virtual human body model for electromagnetic

simulation, and employed the transfer function

approach to estimate temperature rise. They also

explored variables such as lead type, trajectory, and

MRI parameters on RF heating effects(Zeng et al.,

2018). Similarly, Islam et al. investigated RF-induced

heating in partially inserted electrodes in 1.5T MRI

systems, revealing that heating was significantly

influenced by factors such as contact size, spacing,

lead length, and clinically relevant trajectories(Islam

et al., 2023). While this approach has become widely

adopted due to its ability to maintain the complexity

of the implant system’s microstructure, it has some

limitations. The accuracy of FDTD EM simulations

is moderate, and the measurement of transfer

functions requires physical prototypes, making

repeated testing time-consuming and less suitable for

implants with complex and variable wire geometries,

such as cochlear implants. In such cases, alternative

methodologies may offer better efficiency and

precision(Winter et al., 2021).

The assessment of RF-EMF safety requires

consideration of curved components such as birdcage

coils and implant electrodes. In this context, the Finite

Element Method (FEM) emerges as an optimal

approach, offering enhanced precision in analyzing

complex, curved geometries compared to other

techniques(Winter et al., 2021). This paper introduces

a combined electromagnetic and temperature field

simulation method, based on the FEM approach, to

evaluate RF-EMF-induced heating in a cochlear

implant system within a 1.5T MRI coil. The method

facilitates the assessment of heating effects on the

cochlear implant system and investigates the key

factors influencing these thermal effects.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Cochlear Implants

The contemporary generation of cochlear implants

consists of two principal components: the implant and

an external sound processor. The electrode array in

modern cochlear implants typically contains 12 to 22

electrodes, although the exact number may vary

BIODEVICES 2025 - 18th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

120

depending on device design and specific clinical

requirements. This array, approximately 2 cm in

length, is connected to one or more internal current

sources, which are activated based on commands

from the external device(Macherey & Carlyon, 2014).

The external sound processor, worn behind the ear, is

removable and can be detached during magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) examinations. As a result,

this study focuses exclusively on the radiofrequency

electromagnetic field RF-induced heating of the

implant portion.

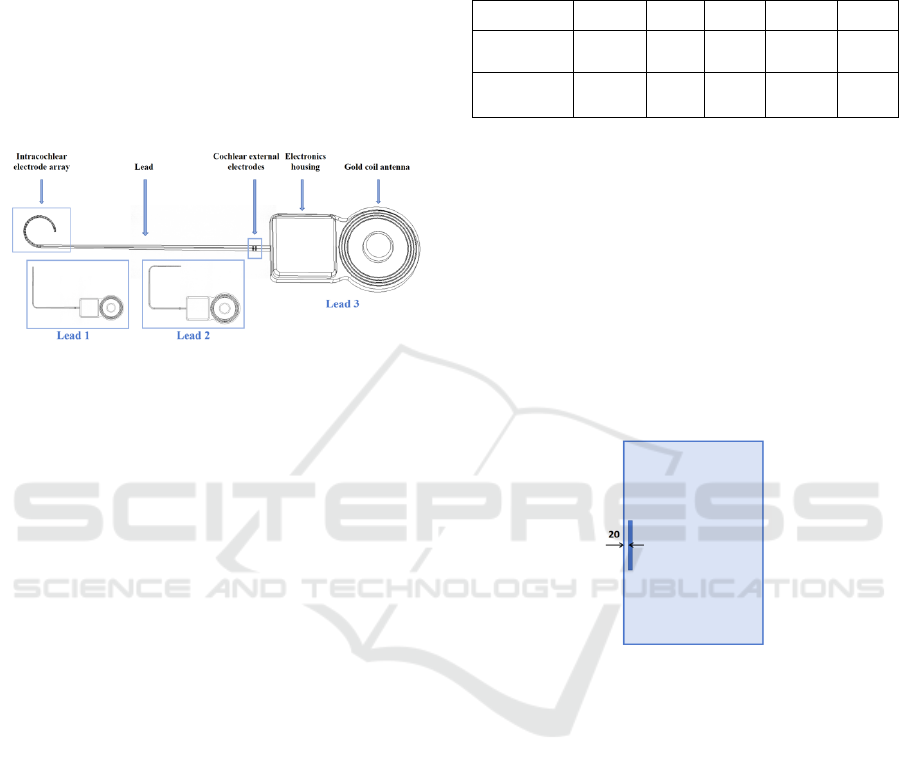

Figure 1: Representative configurations of cochlear

implant.

As illustrated in Figure 1, a typical cochlear

implant designed by Nurotron comprises consists of

several key components, including the intracochlear

electrode array, lead, extracochlear electrodes,

electronic housing, and gold coil antenna. The

intracochlear electrode array is depicted as a 24-

electrode cylinder with radii of 0.4 mm, 0.5 mm, and

0.6 mm, respectively, tapering towards the tip of the

lead. To accommodate the anatomical variation of the

patient’s cochlea and case-specific requirements, the

length of the electrode array can be selected from 17.5

mm, 22.0 mm, or 25.5 mm. Additionally, two

extracochlear electrodes are also implemented in the

system.

2.2 Phantom for Cochlear Implants

The ASTM phantom was used in place of the human

body for the simulation. Since the cochlear implant is

typically implanted in the human cochlea, and the

main components of the cochlear environment

include the cochlear canal as well as internal and

external lymphatic fluids(Fatani et al., 2024), a

configuration simulating the cochlear environment

was incorporated. The specific parameters of this

configuration are presented in Table 1

(Hasgall PA, 2024), where

r

ε is the relative dielectric

constant,

(unit : S / m)σ is the conductivity,

2

k(unit : W / (m K))⋅

is the coefficient of thermal

conductivity,

c(unit : J / (kg K))⋅ is the heat capacity,

3

(unit : kg / m )ρ

is the density.

Table 1: Material parameters.

Phantom

r

ε

σ

k c ρ

ASTM

p

hanto

m

80 0.47 0.57 4150 1050

Cochlear

p

hanto

m

57.75 0.32 0.46 3226 1089

The location and trajectory of the cochlear

implant within the ASTM phantom are illustrated in

Figure 2. The implant is positioned at the center of the

ASTM phantom, 45 mm from both the top and

bottom of the gel, aligned with the aperture direction,

and 2 cm from the sidewalls, where a relatively high

and evenly distributed electric field exists. Given that

RF-induced heating of partially inserted electrodes is

closely correlated with clinically relevant

trajectories(Islam et al., 2023), and cochlear

implantation often involves electrode bending, this

paper discusses several typical simplified cochlear

bending trajectories.

Figure 2: The position and dimension of inserted bone

structure. Unit: mm.

2.3 Coupled EM and Thermal

Simulations

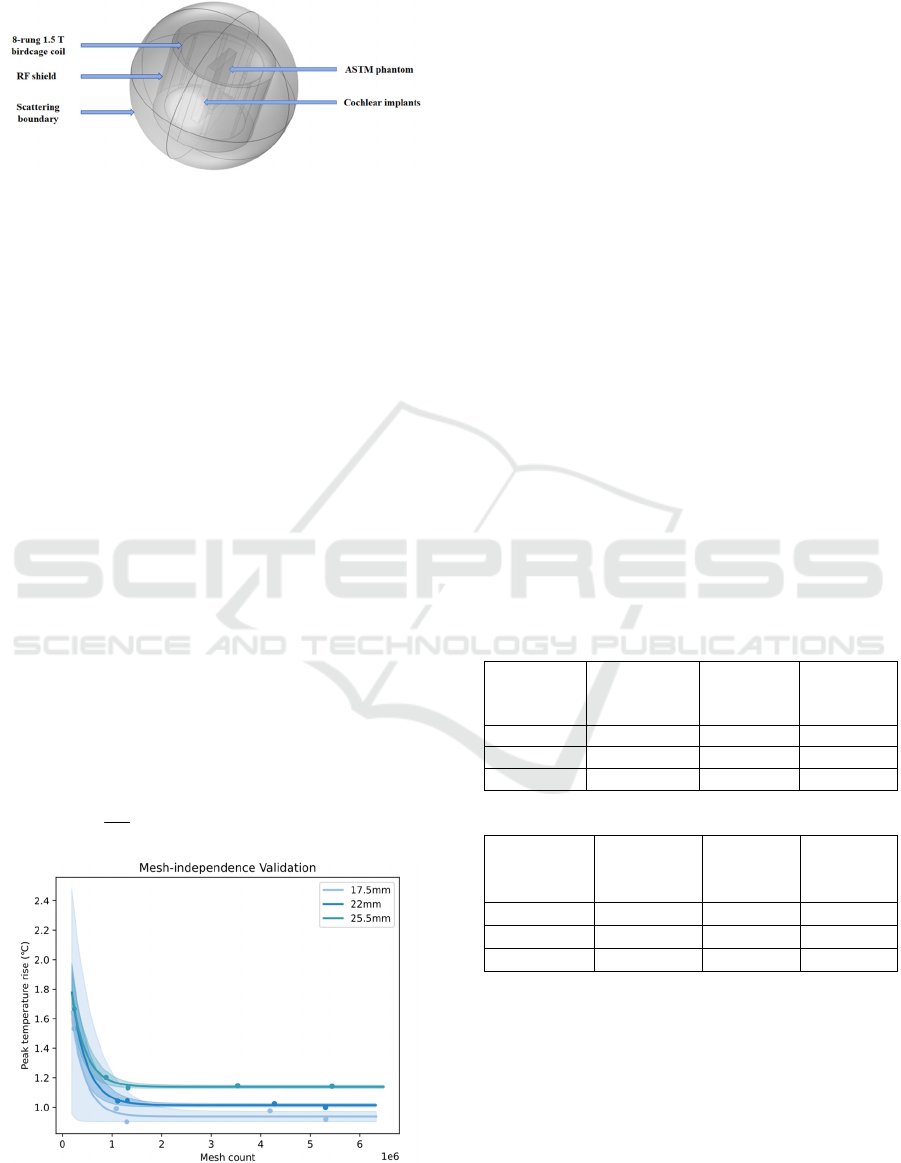

An 8-rung 1.5T low-pass birdcage coil (diameter: 800

mm, length: 700 mm) was used to generate a

circularly polarized electromagnetic field, driven in

quadrature mode at 64 MHz. The ASTM phantom

with the implant was positioned such that the center

of the phantom aligned with the isocenter of the RF

coil. To ensure proper electromagnetic isolation and

stable tuning, an RF shield was integrated around the

exterior of the birdcage coil. Scattering boundary

conditions were applied to truncate the computational

region, effectively simulating real-world conditions.

The initial value of the capacitance was estimated

using the Birdcage Builder Software developed by

Penn State University(Chin et al., 2002). A

subsequent scanning search was conducted in the

Simulation and Evaluation of Thermal Effects Under MRI for Cochlear Implants

121

vicinity of this value to determine the optimal

capacitance, which was approximately 12.3 pF.

Figure 3: Illustration of simulation setup, the position of

various components.

A sequential coupled electromagnetic and thermal

analysis was performed using the Finite Element

Method (FEM) simulation software COMSOL

Multiphysics to calculate the electric and temperature

fields for the ASTM phantom cochlear implant model.

Maxwell's equations were employed to solve the

fluctuating electromagnetic fields at specific points

within the model, influenced by the electromagnetic

field under investigation, in the steady-state

frequency domain. The steady-state electromagnetic

solution of Maxwell's equations provided the heat

source for the transient thermal analysis, which

yielded the electromagnetic solution for all domains

and the heat transfer solution within the ASTM body

model and the implant. Using the SAR as the heat

source for the temperature rise, the temperature field

distribution within the model is obtained by solving

the heat conduction equation through the Finite

Element Method (FEM), as shown in Eq. (1), where

ρ

is the density of the phantom, c is the specific heat

capacity of the phantom,

k is the thermal diffusivity,

T

is the temperature at a point in space,

t

is time and

Q

is the heat source.

22

∂

ρ=∇+=∇+

∂

T

ckTQkTSAR

t

(1)

Figure 4: Illustration of mesh-independence validation.

A non-uniform mesh was utilized in the simulation,

with the mesh density near critical inflection points

selected as the final simulation mesh based on mesh-

independence validation. This approach reduced

computational costs while maintaining accurate

modelling.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

All results were obtained through numerical

simulations using the methodology described above,

with the input power of RF coil normalized to a

whole-body average SAR of 2 W/kg, in accordance

with the IEC 60601-2-33 power limitation criterion

for the MR normal mode of operation(Commission,

2022). This study evaluates RF-induced heating in

two phantoms with three different electrode lengths

and three typical simplified cochlear implant bending

trajectory scenarios. This study will analyze the RF-

induced heating by examining the spatial and

temporal distribution and variation of temperature. It

will focus on potential factors affecting maximum

temperature rise, including electrode length, lead

trajectory, and phantom models.

Table 2: Statistical analysis of temperature rises in phantom

around the lead tip under all the studied exposure

conditions. (Unit:℃)

(a) ASTM phantom

Bending

trajectories

17.5mm

electrode

length

22mm

electrode

length

25.5mm

electrode

length

Lead 1 1.458 1.459 1.461

Lead 2 1.589 1.629 1.746

Lead 3 1.592 1.592 1.597

(b) cochlear phantom

Bending

trajectories

17.5mm

electrode

length

22mm

electrode

length

25.5mm

electrode

length

Lead 1 1.456 1.479 1.518

Lead 2 1.736 1.793 1.898

Lead 3 1.906 1.921 1.922

The statistical results of all simulations are

presented in Table 2. In the ASTM phantom, the

maximum temperature rises for Lead 1, Lead 2, and

Lead 3 were 1.461°C, 1.746°C, and 1.594°C,

respectively. A similar trend was observed in the

cochlear model, where the maximum temperature

rises were 1.518°C, 1.898°C, and 1.956°C for Lead 1,

Lead 2, and Lead 3, respectively. For a given

trajectory, the maximum temperature rise was

BIODEVICES 2025 - 18th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

122

consistently higher in the cochlear phantom

compared to the ASTM phantom.

3.1 Temperature Rise Distribution

By analyzing the spatial distribution of temperature

rise, based on the model's exposure to RF

electromagnetic fields for 15 minutes, as shown in Fig.

5, it can be concluded that in several scenarios

examined in this study, the areas with the highest

temperature increases are concentrated at the ends of

the gold coil, the outer cochlear electrode, and the tip

of the inner cochlear electrode. The hotspot is

primarily located at the tip of the inner cochlear

electrode, which warrants focused attention in further

research. Theoretically, the implant can be considered

an RF antenna that captures energy along its length

and dissipates the maximum energy density near its

end(Pozar, 2021), which aligns with the observed

hotspot at the tip of the intracochlear electrode.

Figure 5: Distribution of temperature rise around the

implant after 15 minutes of exposure.

Figure 6: Temperature rise curves for the maximum

temperature rise case for three bending trajectories.

In the time domain, the temperature rise curve

shown in Fig. 6 exhibits a rapid, near-linear increase,

followed by a gradual leveling off. The rate of

temperature change over time depends on the balance

between the power density absorbed from the RF

source and heat conduction within the phantom

material. As the temperature rise becomes significant,

heat conduction begins transferring heat from the

implant to the surrounding material, which slows the

rate of further temperature increase.

3.2 Electrode Length

Temperature rises were calculated for three electrode

lengths in both ASTM and cochlear phantoms to

investigate the effect of electrode length on RF-

induced heating. The electrode lengths, chosen based

on recommendations from implant surgeons, were

17.5 mm, 22.0 mm, and 25.5 mm to accommodate

different cochlear anatomical structures and case

variations. The type and number of electrodes

remained consistent across lengths, with the primary

difference being the spacing between electrodes. The

mean RF-induced temperature rises for electrode

lengths of 17.5 mm, 22.0 mm, and 25.5 mm were

1.546°C, 1.560°C, and 1.600°C in the ASTM

phantom, and 1.699°C, 1.743°C, and 1.779°C in the

cochlear phantom. As illustrated in Figure 7(a), the

maximum temperature rise tended to increase with

longer electrode lengths in both phantoms.

Figure 7: (a) Line graph showing the average maximum

temperature rise for different electrode lengths in both the

ASTM and cochlear phantoms, (b) line graph showing the

maximum temperature rise for different bending

trajectories in both the ASTM and cochlear phantoms.

When the implant's size is approximately half the

wavelength, a significant temperature rise occurs due

to the resonance effect(Konings et al., 2000). This

resonance phenomenon is heavily influenced by the

electrical properties and the operating frequency of

the medium surrounding the implant. Neglecting

magnetic permeability, the wavelength of an

electromagnetic wave

λ

m

in a given material can be

calculated using Eq. (2), where

0

λ

is the wavelength

of the electromagnetic wave in vacuum and

ε

r is the

relative dielectric constant.

0

λ

λ

ε

=

m

r

(2)

Simulation and Evaluation of Thermal Effects Under MRI for Cochlear Implants

123

The wavelength of an electromagnetic wave in a

vacuum

0

λ

is related to the RF frequency. In this

study, the research focuses on the 1.5T case.

According to Eq. (3), the wavelength can be

calculated as approximately 4.6875m.

0

λ

=

c

f

(3)

The relative permittivity of the ASTM phantom is

80, while that of the cochlear phantom is 57.75. Using

these values and applying Eq. (2), the theoretical half-

wavelengths are calculated as 26.20 and 30.84mm,

respectively, for ASTM and cochlear phantom. The

cochlear implant leads tested thus far have not

reached this length, so, theoretically, the temperature

rise is expected to increase as the lead length

increases. The conclusion that the maximum

temperature rise increases with longer electrode

length aligns with theoretical expectations.

3.3 Bending Trajectory

Cochlear implantation often involves lead bending,

and three typical simplified bending trajectories, as

shown in Fig. 1, were investigated for both the ASTM

and cochlear phantoms. Figure 7(b) illustrates the

surrounding temperature rise for different

implantation trajectories in the two phantoms, with

maximum temperature rises of 1.518°C, 1.898°C, and

1.922°C for trajectories 1, 2, and 3, respectively. It

can be tentatively estimated that trajectories with a

greater degree of curvature and a smaller bending

range will concentrate more heat and cause a larger

temperature rise.

3.4 Phantom Model

The RF-induced thermogenesis of the same implant

differs between the ASTM and cochlear phantoms.

Table 2 and Figure 7 presents histograms of the

maximum temperature rise in both phantoms,

showing that the mean maximum temperature rise in

the ASTM phantom is 1.569°C, which is lower than

the 1.737°C observed in the cochlear phantom. In all

cases, the maximum temperature rise in the ASTM

phantom is lower than that in the cochlear phantom.

Similar to Yang et al.'s study, relying solely on the

ASTM phantom for localized areas may result in

temperature rise deviations(Yang et al., 2024). In this

paper, it is shown as an underestimation of the

maximum temperature rise. Therefore, when

assessing the RF thermogenic safety of cochlear

implants more localized scenarios should be

considered.

4 CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we introduce a model that simulates the

cochlear environment to improve the assessment of

RF-induced heating near cochlear implants. This

model provides results that more accurately reflect

the intracochlear conditions compared to the ASTM

model, verifying that the ASTM model may have

underestimated the maximum temperature rise.

Additionally, we propose a finite element-based

electromagnetic and thermal co-simulation method to

obtain the temperature distribution and maximum

temperature rise from RF thermogenesis. This

approach enables rapid analysis of worst-case implant

configurations and predicts RF thermogenesis

outcomes, helping to guide future experiments and

implant design. Using this method, we examine

factors such as electrode length and wire trajectory,

highlighting the importance of focusing on the

hotspot at the tip of the electrode and emphasizing the

need to control electrode length where possible.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the Key Research and

Development Plan of Zhejiang Province (Grant Nos.

2023C03094) and Zhejiang Provincial Natural

Science Foundation of China under Grant No.

LY22H180006.

REFERENCES

Alberalar, N. D., Reis, J., Piechotta, P. L., Beetz, N. L.,

Fehrenbach, U., Geisel, D., Thomas, A., Busse, H., &

Denecke, T. (2023). Complications of cochlear

implants with MRI scans in different body regions: type,

frequency and impact. Insights into imaging, 14(1), 9.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-022-01353-x

ASTM_International. (2019). Standard Test Method for

Measurement of Radio Frequency Induced Heating On

or Near Passive Implants During Magnetic Resonance

Imaging(F2182‐19e2).

Buchman, C. A., Gifford, R. H., Haynes, D. S., Lenarz, T.,

O'Donoghue, G., . . . Zwolan, T. (2020). Unilateral

Cochlear Implants for Severe, Profound, or Moderate

Sloping to Profound Bilateral Sensorineural Hearing

Loss: A Systematic Review and Consensus Statements.

JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 146(10), 942-953.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0998

Chadha, S., Kamenov, K., & Cieza, A. (2021). The world

report on hearing, 2021. Bull World Health Organ,

99(4), 242-242a. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.21.285643

BIODEVICES 2025 - 18th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

124

Chin, C. L., Collins, C. M., Li, S., Dardzinski, B. J., &

Smith, M. B. (2002). BirdcageBuilder: Design of

Specified-Geometry Birdcage Coils with Desired

Current Pattern and Resonant Frequency. Concepts

Magn Reson, 15(2), 156-163. https://doi.org/10.

1002/cmr.10030

Commission, I. E. (2022). Particular requirements for the

basic safety and essential performance of magnetic

resonance equipment for medical diagnosis.(IEC

60601-2-33 ED4.0).

Crane, B. T., Gottschalk, B., Kraut, M., Aygun, N., &

Niparko, J. K. (2010). Magnetic resonance imaging at

1.5 T after cochlear implantation. Otol Neurotol, 31(8),

1215-1220. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0b013e31

81ec1d61

Fatani, N., Abdelsamad, Y., & Alsanosi, A. (2024).

Influence of Cochlear Anatomy on Intraoperative

Electrically Evoked Compound Action Potentials. J

Clin Med, 13(16). https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm

13164716

Hasgall PA, D. G. F., Baumgartner C, Neufeld E, Lloyd B,

Gosselin MC, Payne D, Klingenböck A and Kuster N.

(2024). IT’IS Database for Thermal and

Electromagnetic Parameters of Biological Tissues,

Version 4.2. https://doi.org/10.13099/VIP21000-04-2.

Islam, M. Z., Hu, W., Guo, R., & Chen, J. (2023). Factors

Affecting the RF-Induced Heating for the Electrodes

Partially Inserted Inside Human Body at 1.5T MRI

2023 IEEE International Symposium on Antennas and

Propagation and USNC-URSI Radio Science Meeting

(USNC-URSI).

Konings, M. K., Bartels, L. W., Smits, H. F., & Bakker, C.

J. (2000). Heating around intravascular guidewires by

resonating RF waves. Journal of Magnetic Resonance

Imaging, 12(1), 79-85.

Koptyug, I., Kovtunov, K., & Svyatova, A. (2023).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). In I. E. Wachs &

M. A. Bañares (Eds.), Springer Handbook of Advanced

Catalyst Characterization (pp. 849-867). Springer

International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-

3-031-07125-6_37

Luechinger, R., Zeijlemaker, V. A., Pedersen, E. M.,

Mortensen, P., Falk, E., . . . Boesiger, P. (2005). In vivo

heating of pacemaker leads during magnetic resonance

imaging. Eur Heart J, 26(4), 376-383; discussion 325-

377. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehi009

Macherey, O., & Carlyon, R. P. (2014). Cochlear implants.

Current Biology, 24(18), R878-R884. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.cub.2014.06.053

Pozar, D. M. (2021). Microwave engineering: theory and

techniques. John wiley & sons.

Ran, G., Jianfeng, Z., & Ji, C. (2017). MRI RF-Induced

Heating in Heterogeneous Human Body with

Implantable Medical Device. In H. Ahmet Mesrur

(Ed.), High-Resolution Neuroimaging. IntechOpen.

https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.71384

Rezai, A. R., Finelli, D., Nyenhuis, J. A., Hrdlicka, G.,

Tkach, J., . . . Shellock, F. G. (2002). Neurostimulation

systems for deep brain stimulation: in vitro evaluation

of magnetic resonance imaging-related heating at 1.5

tesla. J Magn Reson Imaging, 15(3), 241-250.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.10069

Standardization, I. O. f. (2018). Assessment of the safety of

magnetic resonance imaging for patients with an active

implantable medical device(Tech Specif ISOTS 10974

2018, second edition).

Winter, L., Seifert, F., Zilberti, L., Murbach, M., &

Ittermann, B. (2021). MRI-Related Heating of Implants

and Devices: A Review. J Magn Reson Imaging, 53(6),

1646-1665. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.27194

Yang, X., Guo, R., Zheng, J., Long, S. A., Chen, X.,

& Chen, J. (2024). Improved assessment of

radiofrequency electromagnetic field power deposition

near orthopaedic device using a bone-inclusive ASTM

phantom under 1.5 T and 3T MRI. Physics in Medicine

& Biology, 69(16), 165024.

Zeng, Q., Wang, Q., Zheng, J., Kainz, W., & Chen, J.

(2018). Evaluation of MRI RF electromagnetic field

induced heating near leads of cochlear implants. Phys

Med Biol, 63(13), 135020. https://doi.org/10.

1088/1361-6560/aacbf2

Simulation and Evaluation of Thermal Effects Under MRI for Cochlear Implants

125