Assessing Sweden’s Current Cybersecurity Landscape: Implications of

NATO Membership

Nike Henriks

´

en

1

, Isak Lexert

2

, Jakob Bergquist Dahn

2

and Simon Hacks

1 a

1

Department of Computer and System Sciences, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden

2

Halmstad University, Halmstad, Sweden

Keywords:

Cybersecurity, Sweden, NATO Membership, Cyber Defense, Cyber Threats.

Abstract:

Sweden’s recent NATO membership marks a significant shift in the country’s national security strategy, par-

ticularly concerning cybersecurity. This study has assessed the current cybersecurity landscape in Sweden by

conducting interviews with experts within the public sector and through document analysis. The interviewees

included academics, researchers, and government officials from the municipal level to parliament. The study

concludes how the threat environment has evolved following Sweden’s NATO membership. The study has

identified key cyber threats facing Sweden, primarily from state-sponsored actors such as Advanced Persis-

tent Threat (APT) groups and cybercriminal organizations targeting critical infrastructure. The study has also

found disparities in cybersecurity preparedness between Sweden’s military and civilian sectors. The study em-

phasizes the need to strengthen civilian cybersecurity to reach a similar preparedness as the military to adapt

to NATO’s requirements and standards.

1 INTRODUCTION

The geopolitical landscape has shifted since Russia

annexed Crimea in 2014, an event that not only in-

volved traditional military actions but also sophisti-

cated cyber-attacks (Gunawan and Pane, 2024). This

hybrid warfare strategy highlighted the vulnerabilities

of digital infrastructure (Lika et al., 2018). The full-

scale invasion of Ukraine by Russia in 2022 has fur-

ther underlined the importance for Western countries

to improve their cyber defenses (Bran, 2024).

In an increasingly digitized world, societies have

become more vulnerable to cyber-attacks, which can

be orchestrated remotely without breaching physi-

cal borders, thus avoiding declaring war (Springer,

2024). The reliance on digital technology for essen-

tial services creates substantial vulnerabilities. Cyber

adversaries can exploit these weaknesses to conduct

espionage, sabotage, and other malicious activities,

destabilize economies, and compromise national se-

curity (Achterberg, 2022).

Sweden has abandoned its neutrality and joined

NATO in response to growing threats from Russia.

This strategic shift aims to enhance Sweden’s security

but also places it in the crosshairs of cyber attackers.

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0478-9347

The experiences of Finland, which faced increased

cyber threats following joining NATO (Helin and Hi-

manen, 2023; Orange Cyberdefense, 2023), provide

a relevant parallel, suggesting that Sweden could en-

counter similar challenges.

Given Sweden’s new status as a NATO member, it

is crucial to assess the state of its cybersecurity. Un-

derstanding the potential threat actors and their ca-

pabilities is essential for developing defense strate-

gies (Tzu, 2003). This assessment helps identify gaps

in the existing cybersecurity framework and ensures

that governmental and private sectors are prepared to

counter sophisticated cyber threats. To address this

issue, the research questions posed by this study are:

1. What are the current cybersecurity threats facing

Sweden?

2. How has the threat landscape changed following

its NATO membership?

3. What are the implications of the NATO member-

ship on Swedish cybersecurity?

The rest of the article is structured as follows.

Next, the background provides a historical overview

of Sweden’s cybersecurity evolution and NATO’s role

in the cyber domain. Then, the research methodol-

ogy is presented. The results are subdivided to discuss

the current state of cybersecurity in Sweden, identify

Henriksén, N., Lexert, I., Dahn, J. B. and Hacks, S.

Assessing Sweden’s Current Cybersecurity Landscape: Implications of NATO Membership.

DOI: 10.5220/0013117800003899

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2025) - Volume 1, pages 209-216

ISBN: 978-989-758-735-1; ISSN: 2184-4356

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

209

the key threat actors, and analyze how NATO mem-

bership might influence these dynamics. The paper

summarizes the implications of NATO membership

on Sweden’s cybersecurity, highlighting the opportu-

nities and gaps that must be addressed.

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Historical Context of Sweden’s

Cybersecurity

Sweden’s cybersecurity landscape has evolved signif-

icantly, shaped by historical events and a progressive

approach to technology and national security. As one

of the most digitized countries in the world (European

Commission, 2022), robust cybersecurity strategies

are important. In the 1990s, Sweden began develop-

ing its initial cybersecurity policies, which were pri-

marily reactive and focused on safeguarding govern-

ment and military networks (Zieni

¯

ut

˙

e, 2022). How-

ever, the global surge in cyber threats during the

2000s prompted Sweden to broaden its cybersecu-

rity efforts. Commercial security solutions were in-

troduced to protect customers navigating the internet,

where hackers had discovered numerous new attack

methods (Zieni

¯

ut

˙

e, 2022). A significant milestone

in Sweden’s cybersecurity strategy was the estab-

lishment of the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency

(MSB) in 2009. MSB and other agencies were

tasked with coordinating and strengthening national

preparedness against various threats, including those

in cyberspace (Wennerstr

¨

om et al., 2015).

The 2010s and the beginning of the 2020s have

been a pivotal time for Sweden’s cybersecurity. In

2016, the Swedish government launched the ”Na-

tional Cybersecurity Strategy,” reflecting a compre-

hensive and proactive approach to cybersecurity,

which aimed to enhance national resilience, protect

critical infrastructure, and foster a culture of cy-

bersecurity awareness among citizens and organiza-

tions (Justitiedepartementet, 2017).

The increased need for international cooperation

and the growing threat of cyberattacks led MSB

to survey how effectively Swedish public organi-

zations implement systematic information and cy-

bersecurity practices (Swedish Civil Contingencies

Agency (Myndigheten f

¨

or samh

¨

allsskydd och bered-

skap, MSB), 2023). The survey results indicated that

only 31 % of public organizations met basic require-

ments (Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency (Myn-

digheten f

¨

or samh

¨

allsskydd och beredskap, MSB),

2023). The absence of basic cyber security portrayed

by MSB lays the foundation for a governmental ini-

tiative to develop an updated national strategy, which

is currently an ongoing effort orchestrated by the

Swedish government (Swedish Government, 2024a).

Despite these challenges, Sweden is highly ranked in-

ternationally in the Global Cybersecurity Index 2024

(ITU)

1

.

2.2 Cybersecurity in NATO

Recently, NATO has confronted new challenges, in-

cluding hybrid warfare and cybersecurity threats. To

address these issues, NATO has undertaken initiatives

to adapt and modernize its capabilities and enhance its

resilience to emerging threats. At the Warsaw Sum-

mit in 2016, NATO declared cyberspace a military do-

main for the first time, marking the start of extensive

efforts to foster cooperation within the alliance on cy-

ber security (Jacobsen, 2021).

In 2021, during the Brussels Summit, NATO

approved a comprehensive cyber defense policy,

committing to deter, defend against, and ac-

tively counter cyber threats (Swedish Government,

2024b). Allied members also acknowledged the

potential to invoke Article 5 in response to sig-

nificant cyberattacks (Swedish Government, 2024b).

The 2023 Vilnius Summit approved a new con-

cept to amplify NATO’s commitment to deterrence

in cyberspace (North Atlantic Treaty Organization

(NATO), 2024). During the summit, NATO launched

the Virtual Cyber Incident Support Capability (North

Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), 2024), de-

signed to assist efforts in deterring cyberattacks.

NATO operates additional entities within the cy-

ber domain with various functions. These include the

NATO Communications and Information Agency Cy-

ber Security Centre (NCSC) in Belgium, the NATO

Cyberspace Operations Centre in Belgium, focus-

ing on military operations, and the NATO Coop-

erative Cyber defense Centre of Excellence (CCD-

COE), which is dedicated to training, development,

and research in the field of cybersecurity (North At-

lantic Treaty Organization (NATO), 2024). Swe-

den has a history of active and successful participa-

tion in NATO’s cyber defense initiatives, particularly

through the CCDCOE collaborative exercises

2

.

2.3 Related Work

Previous research indicated that Finland’s ascension

into NATO brought about more cybersecurity oppor-

tunities, even as it identified the cyber domain as an

1

https://shorturl.at/AlnZ8

2

https://shorturl.at/BwqqF

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

210

unpredictable environment with potential threats (He-

lin and Himanen, 2023). Building on the compari-

son with Finland, the current study shifted focus to

Sweden, aiming to assess the impact of its entry into

NATO on Swedish cybersecurity.

Joe Burton investigated NATO’s strategic chal-

lenges concerning cyber defense capabilities and

emphasized how the alliance should address these

threats (Burton, 2015). Burton’s research underscored

the significant unity within NATO on key cybersecu-

rity issues. Nevertheless, Burton’s study did not delve

into the specific threat landscape concerning individ-

ual member states or how national cybersecurity ef-

forts aligned with NATO’s broader structures. By ad-

dressing these gaps through interviews with experts

in Swedish cybersecurity, our study aims to generate

valuable insights into the implications of NATO mem-

bership for Sweden’s cybersecurity.

Further research had documented trends of con-

tradictory cyberattacks and hybrid warfare targeting

NATO and EU member states (Poptchev, 2020). This

study also analyzed the conceptual frameworks and

policy guidelines of NATO, the European Union, and

the United States, highlighting that transatlantic co-

operation in the cyber domain was crucial for the se-

curity and stability of involved nations. Our work

echoes these findings, emphasizing Sweden’s expe-

riences upon joining NATO. Another study (L

´

et

´

e and

Pernik, 2024) asserted that the EU and NATO shared

a common threat landscape and should address these

challenges through joint exercises and collaborative

efforts. However, their research did not examine the

role of third-party nations. By navigating the com-

plex cybersecurity frameworks of both NATO and the

EU, our work aims to conclude Sweden’s cybersecu-

rity posture following its NATO membership.

3 RESEARCH METHOD

To assess Sweden’s cybersecurity threats in light of

its recent NATO membership, this study employs a

qualitative research methodology involving indepen-

dent investigations by two researcher groups. Each

group planned and conducted their interviews inde-

pendently to minimize bias and enhance the validity

of the findings. The results presented later in this

study are the consolidated and validated outcomes de-

rived from both independent investigations.

3.1 Data Collection

The first research group utilized a qualitative ethno-

graphic approach (Hammersley and Atkinson, 1992),

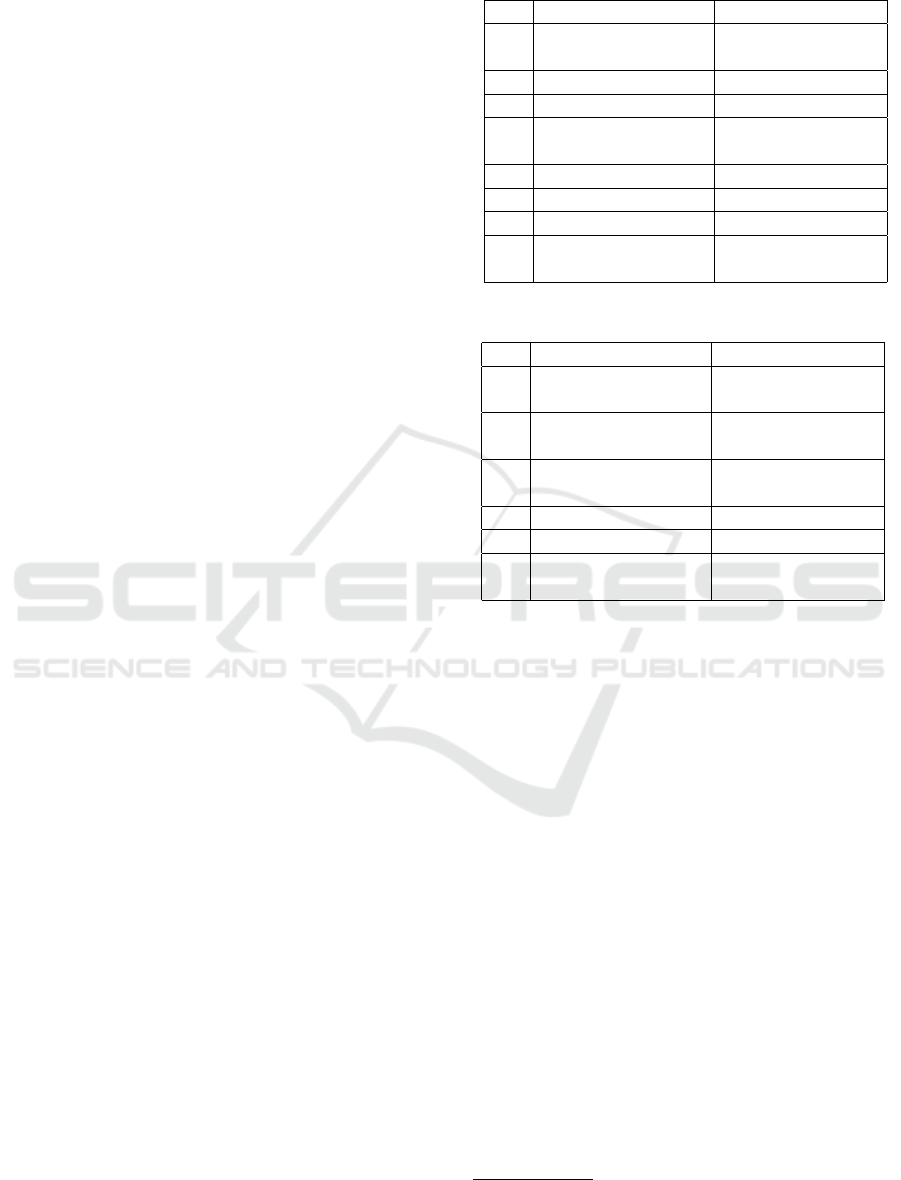

Table 1: Participants of Research Group 1.

ID Organization Professional Role

1.1 Academia and Se-

curity Authority

PhD Student, Offi-

cer

1.2 Security Authority Officer

1.3 Academia Professor

1.4 Academia Postdoc, Cyber

Security Consult

1.5 Academia Postdoc

1.6 Academia PhD Student

1.7 Security Authority Anonym

1.8 Private Company Cyber Security

Consult

Table 2: Participants of Research Group 2.

ID Organization Professional Role

2.1 Local Government

Organization

Cyber Security

Consult

2.2 Municipality Cyber Security

Consult

2.3 Municipality Head of Software

Development

2.4 Parliament Politician

2.5 Academia Postdoc

2.6 Government Cyber Security

Political Advisor

focusing on semi-structured interviews with cyberse-

curity experts from various sectors. Each interview

lasted 60 to 90 minutes and was conducted in April or

May 2024. The second research group also adopted

a qualitative approach. The interviews conducted by

this group also ranged from 60 to 90 minutes and were

conducted in March or April 2024

3

.

3.2 Participants

The participants for both sets of interviews were se-

lected based on their expertise and roles in cyberse-

curity. The groups interviewed eight, respectively,

six experts, ensuring a diverse representation of per-

spectives and experiences. The participants were con-

nected throughout their intensive network. However,

we cannot go into more detail about the organizations

included due to secrecy issues. The details of the par-

ticipants are summarized in the tables 1 and 2.

3.3 Data Analysis

Both groups employed thematic analysis (Braun and

Clarke, 2006) to interpret the data from their inter-

3

All interview questions can be found at https://shorturl.

at/DlBiY.

Assessing Sweden’s Current Cybersecurity Landscape: Implications of NATO Membership

211

views. This involved coding the interview transcripts

to identify recurring themes and patterns related to

cybersecurity threats and NATO membership, using

mind maps and a systematic categorization of themes

that allowed for a structured and detailed analysis.

To ensure the findings’ robustness, the two sets

of results were compared and validated against each

other. Any discrepancies were discussed between the

two groups guided by the senior authors and resolved

through a consensus process. The independent nature

of the research groups, combined with the rigorous

data collection and analysis methods, provides a high

confidence level in the validity and reliability of the

study’s findings. The subsequent sections will present

the consolidated results, highlighting the key themes

and insights from the interviews.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Current State

The Swedish government has delegated the responsi-

bility for national cybersecurity to the Swedish Na-

tional defense Radio Establishment (FRA) alongside

the Swedish Armed Forces, MSB, and the Swedish

Security Service (S

¨

APO), which together have estab-

lished a National Cybersecurity Center (NCSC) (Na-

tional Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), 2024). This

center collaborates with the Swedish Post and Tele-

com Authority (PTS), the Swedish Police Author-

ity, and the Swedish defense Materiel Administration

(FMV). The primary mission of NCSC is to coordi-

nate efforts against cyberattacks and other IT inci-

dents, promote communication regarding vulnerabil-

ities and risks, and serve as a national platform for

information exchange with private and public stake-

holders in the cybersecurity domain (National Cy-

ber Security Centre (NCSC), 2024). In addition

to the NCSC, there is also the Swedish Computer

Emergency Response Team (CERT-SE), which serves

as Sweden’s national computer security incident re-

sponse team (CSIRT) (Swedish Government, 2024a).

Their main task is to manage and prevent IT security

incidents, covering both the public and private sec-

tors, focusing on critical societal functions (CERT-

SE, 2024). CERT-SE collaborates with the NCSC

and is crucial in sharing information regarding current

vulnerabilities and threats, which can prevent attacks

on Swedish entities (CERT-SE, 2024).

Another critical factor to consider in the current

state of Swedish cyber defense is the concept of to-

tal defense. As interview participant 2.4 states: “...it

is important for Sweden as a nation to understand

that it is not solely the Swedish Armed Forces who

becomes a member in NATO, it is the society as

a whole and therefore every organization must take

their responsibility for cybersecurity.” Each civil de-

fense organization must consider its role and whether

it is prepared for it. This is important consider-

ing the results from MSB’s study “Infos

¨

akkollen”

4

which shows that almost 7 out of 10 public or-

ganizations in Sweden do not reach level 1 on a

scale of 0 through 4 (Swedish Civil Contingencies

Agency (Myndigheten f

¨

or samh

¨

allsskydd och bered-

skap, MSB), 2023). The results indicate a gap be-

tween military defense and civil defense in the current

state of preparedness regarding joining NATO.

When considering the current state of Swedish cy-

bersecurity, one must also consider NATO’s cyber ca-

pabilities since they directly impact national cyberse-

curity. Beyond cyber concepts and policies, NATO

operates several entities within the cyber domain that

could serve alongside Swedish cyber capabilities if

needed. However, the new context of being a member

of NATO does not come without expectations. Article

3 in the NATO treaty expects allied members to fulfill

the “Seven Baseline Requirements,” which is focused

on providing a resilient society and covers cyber se-

curity (North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO),

1949). This could challenge Swedish Cyber Security

since organizations must adapt to NATO standards.

4.2 Threat Landscape and Threat

Actors

Our interviewees indicate that numerous countries

can conduct cyberattacks. This includes attacks that

can be categorized as armed attacks—actions permis-

sible within peacetime and not subject to laws of war.

Thus, it remains crucial to underscore the importance

of preparatory information gathering conducted by

entities during periods of peace (Swedish Civil Con-

tingencies Agency (Myndigheten f

¨

or samh

¨

allsskydd

och beredskap, MSB), 2020).

In a report on cyber threats against Sweden, RISE

highlighted that the greatest threat is believed to come

from other states, particularly in light of the dete-

riorating security situation and the expanding threat

landscape. This is mainly due to the means and re-

sources available to state-supported actors, which can

have severe consequences and cause significant dam-

age. These attacks not only target critical infrastruc-

ture but can also harm Sweden’s reputation both inter-

nationally and domestically. Such impacts can lead to

4

Infos

¨

akkollen is an initiative by MSB to help organi-

zations improve their information security practices.

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

212

public concern and diminished confidence in Swedish

authorities, the government, and societal division (Re-

search Institutes of Sweden (RISE), 2022).

Even though the threat landscape, resources, and

the number of threat actors are increasing, ”...Swe-

den ranks second, after Denmark, as the most cyber-

secure country to live in.” (Liljeberg and Oksanen,

2022). Nevertheless, it is highlighted that Sweden’s

security situation has evolved and worsened. More-

over, Swedish citizens are, according to our partici-

pants, generally naive and need more security aware-

ness despite being informed about the current global

situation. This lack of security awareness and how

individuals manage information can significantly im-

pact security facets and overall defense.

Our results indicate that cyber threats and attacks

have increased, which interview participant 1.6 em-

phasizes: ”the threats and attacks will increase. We

are now part of an alliance where members share

and store data and information.” and thereby gain-

ing greater access to information. Considering that

Sweden is one of the world’s most digitized coun-

tries, it is natural for cyberattacks to increase along-

side digitization. Among these, technical intelligence

gathering within the cyber domain seriously threat-

ens Swedish interests, including intelligence collec-

tion by foreign powers. In this context, it has be-

come a trend in the cyber sphere to identify, map,

and exploit system vulnerabilities to access critical

information stored digitally. These cyber intrusions

can impact and restrict Sweden’s political maneuver-

ability, posing a severe threat to the Armed Forces

and the country as a whole (Swedish Armed Forces

(F

¨

orsvarsmakten), 2024). However, while member-

ship may expand the threat landscape, it also enhances

cyber security, notably since cyberspace is recognized

as an operational domain within NATO. Interview

participant 2.4 emphasized this enhanced cybersecu-

rity: “[...] but it also affects us in that we have better

protection against it [cyber threats], as it falls under

one of NATO’s operational domains. It is paradoxical

that in terms of security politics, [...] the threat level

is increasing, but at the same time, it has also become

more secure.”

The most prominent threat actors consist of ad-

vanced, state-sponsored groups, known as Advanced

Persistent Threat (APT) groups, as well as crimi-

nal actors and networks. In its 2022 annual review,

the Swedish Military Intelligence and Security Ser-

vice (MUST) substantiates that cyber threat actors

are predominantly associated with foreign state enti-

ties or are motivated by financial incentives. MUST

also underscores the increasing sophistication and

success of cybercriminal activities (Swedish Armed

Forces (F

¨

orsvarsmakten), 2023). APT groups pos-

sess substantial resources and technical expertise, fre-

quently conducting attacks with targeted objectives

such as espionage, sabotage, or the exfiltration of

sensitive information. MUST’s annual report and

our participants emphasize the advanced and sophisti-

cated cyber capabilities and threats from foreign pow-

ers, particularly the prominent and well-resourced

actors Russia and China. In contrast, criminal ac-

tors are predominantly motivated by financial gain.

This cyber threat category is increasingly prevalent,

driven by a profitable business model for ransomware

alongside activities motivated by extortion and sabo-

tage (Swedish Armed Forces (F

¨

orsvarsmakten), 2023;

Swedish Armed Forces (F

¨

orsvarsmakten), 2024).

Our interviews highlight significant concerns

about the accessibility and leakage of personal in-

formation, notably the potential exposure of medi-

cal data of Swedish citizens. This includes sensi-

tive information such as medical prescriptions, health

records, mental health statuses, and other confidential

data that could be misappropriated. Such information

could then be utilized as a substantial tool for extor-

tion, particularly by state-sponsored actors, targeting

individuals across different sectors of society.

4.3 Indication for Sweden’s

Cybersecurity

4.3.1 The Distinction Between Cyber Defense

and Cybersecurity

According to participants 2.4 and 2.6, there is a dis-

tinction between cyber defense and cybersecurity in

Sweden. Cyber defense is the responsibility of the

Swedish armed forces, including both offensive and

defensive operations in the cyber domain. Each plays

a distinct role within the national security framework.

Participant 2.6 further stated that this distinction is as

pronounced within NATO: “In NATO, the umbrella

term ‘cyber defense’ is used to cover several differ-

ent areas, including resilience, offensive capabilities,

political dialogue, and the protection of the alliance’s

networks.” The participant expressed concern that this

terminology might lose important nuances, especially

compared to the Swedish context, where cyber de-

fense and cybersecurity are often viewed as separate

yet complementary areas.

In contrast, cybersecurity protects Sweden’s civil-

ian digital infrastructure, covering governmental, in-

dustrial, and public networks. Participant 1.2 explains

the importance of distinguishing between civilian and

military cyber defense, referring to it as a relatively

new concept. The participant also emphasizes that

Assessing Sweden’s Current Cybersecurity Landscape: Implications of NATO Membership

213

the development of cyber defense will continue to

evolve for a long time. While the military’s cyber de-

fense is well-developed, the civilian sector faces chal-

lenges, particularly in coordinating cybersecurity ef-

forts across various agencies and sectors. This dis-

tinction is crucial in light of Sweden’s recent NATO

membership, which introduces new threats and neces-

sitates further development of civilian cybersecurity

measures to align with NATO standards.

4.3.2 Sweden’s Cyber Defense Capabilities

Within NATO

Sweden’s cyber defense, managed by the Armed

Forces, has been developed through years of close

cooperation and joint exercises with NATO (Swedish

Government, 2024c). This collaboration has allowed

the Swedish military to align its cyber defense prac-

tices with the alliance’s, ensuring compatible oper-

ations, tactics, and communication protocols. As a

result, Sweden’s military cyber units are prepared to

integrate into NATO’s cyber defense framework. As

a member of the alliance, Sweden will benefit from

shared resources, expertise, and technical capabili-

ties to strengthen its cyber defense. Interview par-

ticipant 1.1 emphasizes that “if something impacts a

NATO country, NATO has cyber defense capabilities

that can be rapidly deployed to provide on-site assis-

tance. This concrete situation could happen if Swe-

den faced issues that affected its defense or critical

societal functions.” Member states will be even bet-

ter equipped to respond to and manage various cy-

ber threats by accessing a broader and more diver-

sified pool of resources and expertise. Additionally,

MUST assesses that a Swedish and Finnish NATO

membership enhances the conditions for military de-

fense across all Nordic and Baltic countries (Swedish

Armed Forces (F

¨

orsvarsmakten), 2023).

Sweden’s transition into full NATO membership

will not require significant changes in its military

cyber defense structure. The interoperability be-

tween Sweden’s cyber defense forces and NATO has

been established through collaborations, proving the

Swedish Armed Forces are experienced in NATO’s

operational standards in contradiction to civil cyber

security. This readiness enables Sweden to contribute

to collective defense initiatives.

4.3.3 Challenges for Civil Cybersecurity

Post-NATO Membership

The civilian cybersecurity sector in Sweden faces

significant challenges following NATO membership.

Unlike the military sector, which has been actively

involved in international defense collaborations, the

civilian side lacks the same level of experience and

preparedness. This is particularly evident in the di-

verse cybersecurity maturity levels among civil-sector

organizations. Interview participant 2.3 emphasized

that “public sector organizations might have to meet

higher cybersecurity standards than private ones to

join NATO, due to their roles in national security or

critical services”. According to Participant 2.1, some

agencies have implemented cybersecurity measures,

while others, especially at the municipal level, are still

working to establish basic security protocols.

Another challenge pointed out by Participant 2.1

is the dependency on directives and guidelines from

higher government levels, which has led to delays in

the implementation of cybersecurity measures within

the civilian sector. Public sector organizations await

further instructions on adapting to the new security

demands imposed by NATO membership due to the

nature of public administration management (Partici-

pant 2.6). Interviews with public sector officials (par-

ticipants 2.1, 2.2, and 2.3) reveal that few organiza-

tions are actively aligning their cybersecurity strate-

gies with the requirements of NATO membership.

To meet these challenges, there is a need for a

more comprehensive national cybersecurity strategy

that can be uniformly applied across all civilian sec-

tors, according to Participant 2.1. Participant 2.6 ac-

knowledged that this is currently being worked on.

This could include improving incident response ca-

pabilities and establishing better coordination mecha-

nisms between public sector entities. However, neces-

sary cybersecurity improvements are not consistently

implemented across the public sector. Some agencies

have started to review their cybersecurity protocols

and are considering necessary adaptations, but these

efforts are not widespread across the sector.

4.4 Discussion

Sweden encounters an increasingly complex and dy-

namic landscape of cybersecurity threats. This shift is

attributed to several factors, most notably the global

increase in cyber threats driven by digitalization, im-

pacting the threat landscape in Sweden. The cyber-

security threat in Sweden has also been significantly

influenced by the more challenging security environ-

ment and the growing threat landscape both interna-

tionally and domestically. In light of these circum-

stances, it is plausible that the most significant threat

originates from other states, which possess substantial

resources to carry out significant attacks. Given the

challenging security situation, these targeted cyberat-

tacks could affect critical infrastructure and have far-

reaching consequences on Sweden’s reputation and

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

214

citizens. Such incidents could severely damage Swe-

den’s international and domestic reputation, which,

in turn, could profoundly impact the public, leading

to widespread concern, diminished trust, and societal

fragmentation within Sweden.

Despite Sweden’s high ranking as a cyber-secure

country, its citizens have poor security awareness, af-

fecting other aspects of its security. The primary

threat within Sweden stems from advanced, state-

sponsored groups and cybercriminal groups with

varying motives. Another significant threat is gath-

ering technical intelligence within the cyber domain,

which poses a considerable risk to Swedish interests,

mainly through foreign espionage—primarily from

Russia and China. Identifying and exploiting sys-

tem vulnerabilities to access critical digital informa-

tion undermines Sweden’s political maneuverability

and threatens the security of its Armed Forces.

When Finland joined NATO, an increased fre-

quency of cyberattacks by politically motivated ac-

tors against the country was observed, which can be

linked to its membership. A clear trend is the height-

ened frequency and complexity of these cyber threats,

which increases the vulnerability of organizations that

do not adhere to the necessary cybersecurity standards

and measures. A significant difference might be that

Sweden is now part of an alliance where data and in-

formation are stored and shared among its members,

thereby gaining greater access to valuable informa-

tion. This information could become an appealing

target for groups such as APT actors. This, in turn,

means that the threat level has, in a sense, increased.

However, by joining NATO, Sweden has gained a dif-

ferent type of protection and may be considered more

secure due to its membership. As Participant 2.4 ex-

pressed, there has been something of a ”countercycli-

cal escalation” in these challenging times of security

politics, which, through the membership, can be sum-

marized as an increase in the threat level, but also a

heightened sense of security.

The change and increase in cyber threats against

Finland have captured Sweden’s attention, suggesting

that Sweden could face similar challenges and thus

serve as a reference point for assessing how the threat

landscape might evolve following its NATO member-

ship. Although NATO membership is still recent for

Sweden, the country will closely monitor the develop-

ment of cyber threats and attacks over the long term.

As a full member of NATO, the national cyber-

security landscape changes. Sweden must align its

security strategy with NATO’s security framework

while maintaining digital sovereignty. The results in-

dicate a discrepancy between military cyber defense

and cybersecurity strategies within public entities. It

is reasonable to assume that the discrepancy between

military cyber defense and civilian cybersecurity is

due to differences in historical experience working

within NATO structures, with the former having sig-

nificantly more history with NATO. However, the dis-

crepancy within public entities is more ambiguous

and likely more multifaceted. Part of it could be ex-

plained by complex requirements in various directives

and frameworks organizations must adhere to.

These directives and frameworks could contribute

to a better understanding of which measures need

to be prioritized and implemented for fundamental

cybersecurity, thereby reducing the discrepancy be-

tween organizations. Despite this, most public enti-

ties need more basic cybersecurity. However, NATO

membership can create conditions to strengthen na-

tional unity and reduce the discrepancy by, on a po-

litical level, setting clearer requirements for which

cybersecurity-related components must be in place.

Another perspective is how the Swedish total de-

fense and public-private partnerships can enhance

national cybersecurity. As Sweden integrates into

NATO’s cybersecurity framework, collaboration be-

tween public entities and private sector companies be-

comes increasingly crucial. Private companies may

possess advanced technological capabilities and inno-

vative solutions that complement public sector prac-

tices. By fostering strong partnerships, Sweden could

leverage the expertise and resources of the private sec-

tor to address cybersecurity gaps and enhance overall

resilience. Additionally, these partnerships can facili-

tate sharing threat intelligence and best cybersecurity

practices, ensuring a more coordinated and compre-

hensive approach to national cybersecurity. This col-

laborative approach can help close the gap between

military and civilian cybersecurity.

5 CONCLUSION

This study aimed to investigate the current cyberse-

curity landscape in Sweden within the context of its

NATO membership, focusing on three principal re-

search questions: (1) What are the current cyberse-

curity threats facing Sweden? (2) How has the threat

landscape evolved following Sweden’s NATO mem-

bership? (3) What are the implications of NATO

membership for Swedish cybersecurity?

(1) the research identified several threats, includ-

ing state-sponsored cyberattacks on critical infras-

tructure, ransomware incidents, and increased disin-

formation campaigns. Additionally, vulnerabilities in

outdated systems were highlighted as a notable risk.

(2) Sweden’s NATO membership has transformed

Assessing Sweden’s Current Cybersecurity Landscape: Implications of NATO Membership

215

the threat landscape, making Sweden a more promi-

nent target for cyberattacks. This transformation is

primarily attributed to enhanced data sharing within

NATO, which introduces new risks and potential ad-

vantages. State-sponsored actors, particularly from

nations such as Russia and China, pose significant

risks by targeting Sweden’s critical infrastructure and

exploiting vulnerabilities in its digital defense.

(3) the findings suggest that NATO membership

brings benefits and obstacles to Sweden’s cyberse-

curity posture. While Sweden’s military cyber de-

fense capabilities are well-positioned to integrate into

NATO frameworks, the civilian sector faces consid-

erable difficulties, particularly at local and municipal

levels. The integration into NATO has emphasized the

need for updated cybersecurity strategies to address

deficiencies within the civilian sector.

This study focused on the public sector; there-

fore, future research should explore how these impli-

cations and security measures affect individuals per-

sonally. Another potential area could involve investi-

gating how future collaborations might be conducted

and how to enhance civilian cybersecurity to keep

pace with military cyber defense. Additionally, mon-

itoring the evolution of cyber threats and their future

trajectory within the context of NATO is important.

REFERENCES

Achterberg, B. (2022). Blackout in germany: What happens

when millions lose power for days. Accessed: 2024-

08-28.

Bran, A.-C. (2024). Trends in the political economy of mili-

tary expenditure. the case of europe. In Proceedings of

the International Conference on Business Excellence.

Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis

in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology,

3(2):77–101.

Burton, J. (2015). NATO’s cyber defence: strategic chal-

lenges and institutional adaptation. Defence Studies,

15(4):297–319.

CERT-SE (2024). Om cert-se. Accessed: 2024-08-28.

European Commission (2022). Digital economy and society

index (desi) 2022. Accessed: 2024-08-28.

Gunawan, Y. and Pane, M. E. R. (2024). Responsibility for

excessive infrastructure damage in attacks: Analyzing

russia’s attack in ukraine. Petita: Jurnal Kajian Ilmu

Hukum dan Syariah, 9(1):–.

Hammersley, M. and Atkinson, P. (1992). Ethnography:

Principles in practice. Journal of Qualitative Re-

search, 3:1–19.

Helin, A. and Himanen, P. (2023). Joining NATO: Effects

on finland’s cyber security. Technical report, Laurea

University of Applied Sciences.

Jacobsen, J. T. (2021). Cyber offense in NATO: challenges

and opportunities. International Affairs, 97(3):703–

720.

Justitiedepartementet (2017). Nationell strategi f

¨

or

samh

¨

allets informations- och cybers

¨

akerhet. Ac-

cessed: 2024-08-28.

Lika, R. A., Murugiah, D., Brohi, S. N., and Ramasamy, D.

(2018). NotPetya: Cyber attack prevention through

awareness via gamification. In Proceedings of the

International Conference on Smart Computing and

Electronic Enterprise (ICSCEE).

Liljeberg, J. and Oksanen, P. (2022). Cybers

¨

akerhet. Ac-

cessed: 2024-08-28.

L

´

et

´

e, B. and Pernik, P. (2024). EU-NATO cybersecurity

and defense cooperation: Common threats, common

solutions. Accessed: 2024-08-28.

National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) (2024). V

˚

art upp-

drag. Accessed: 2024-08-28.

North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) (1949). The

north atlantic treaty, article 3. Accessed: 2024-08-28.

North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) (2024). Cyber

defence. Accessed: 2024-08-28.

Orange Cyberdefense (2023). Ett NATO-medlemskap kan

generera cybers

¨

akerhetsattacker mot svenska verk-

samheter. Accessed: 2024-08-28.

Poptchev, P. (2020). NATO-EU cooperation in cybersecu-

rity and cyber defence offers unrivalled advantages.

Information & Security: An International Journal,

45:35–55.

Research Institutes of Sweden (RISE) (2022). Cy-

bers

¨

akerhet: Rapport. Accessed: 2024-08-28.

Springer, P. J. (2024). Cyber Warfare. Contemporary World

Issues.

Swedish Armed Forces (F

¨

orsvarsmakten) (2023). MUST

˚

ars

¨

oversikt 2022. Accessed: 2024-08-28.

Swedish Armed Forces (F

¨

orsvarsmakten) (2024). MUST

˚

ars

¨

oversikt 2023. Accessed: 2024-08-28.

Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency (Myndigheten f

¨

or

samh

¨

allsskydd och beredskap, MSB) (2020). Cy-

bers

¨

akerhet i sverige 2020: Hot, metoder, brister och

beroenden. Accessed: 2024-08-28.

Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency (Myndigheten f

¨

or

samh

¨

allsskydd och beredskap, MSB) (2023). In-

fos

¨

akkollen 2023.

Swedish Government (2024a). Nationell strategi f

¨

or

samh

¨

allets informations- och cybers

¨

akerhet. Ac-

cessed: 2024-08-28.

Swedish Government (2024b). St

¨

arkt f

¨

orsvarsf

¨

orm

˚

aga.

Swedish Government (2024c). Sveriges och NATOs histo-

ria. Accessed: 2024-08-28.

Tzu, S. (2003). The Art of War. Penguin Books, New York,

NY.

Wennerstr

¨

om, E. O., Sand

´

en, M., and Arrland, P. (2015).

Informations- och cybers

¨

akerhet i sverige: Strategi

och

˚

atg

¨

arder f

¨

or s

¨

aker information i staten. Accessed:

2024-08-28.

Zieni

¯

ut

˙

e, U. (2022). Cybers

¨

akerhetens historia. Accessed:

2024-08-28.

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

216