A Serious Game for Early Detection and Assessment of Social Apathy: A

Pilot Study

Cristina D

´

ıez Bort

1,2 a

, Razeen Hussain

1 b

, Valeria Manera

3 c

, Manuela Chessa

1 d

and Fabio Solari

1 e

1

DIBRIS, University of Genoa, Genoa, Italy

2

School of Aerospace Engineering and Industrial Design, Universitat Polit

`

ecnica de Val

`

encia, Valencia, Spain

3

CoBTeK Laboratory, Universit

´

e C

ˆ

ote d’Azur, Nice, France

Keywords:

Apathy, Serious Games, Mild Cognitive Impairment, Human Computer Interaction.

Abstract:

With increasing life expectancy, the prevalence of age-related disorders such as dementia, often preceded by

mild cognitive impairment (MCI), has risen significantly. Among the early signs of cognitive decline, social

apathy stands out as a key indicator, associated with an increased risk of progression to dementia. In this

context, we present ApathySEED, a serious game developed to assess social apathy in individuals with MCI.

The game uses decision-making in social scenarios to evaluate apathy across initiative, interest, and emotion

subdomains. A pilot study involving 33 healthy participants was conducted to validate the game’s usability and

effectiveness as a tool for assessing social apathy. Standardized questionnaires, including SUS, NASA-TLX,

and AMI, were used to measure game performance, cognitive load, and apathy levels. Results suggest that

ApathySEED is a promising tool for apathy assessment, with low cognitive load and high usability, making it

suitable for future clinical utilization.

1 INTRODUCTION

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a common con-

dition among the elderly, bridging normal aging and

more severe cognitive decline, such as Alzheimer’s

disease (AD). It involves memory and attention

deficits without major impact on daily life. With no

cure for AD or dementia, early detection is vital (Et-

gen et al., 2011). Social apathy, marked by reduced

interest and engagement in interactions, is a key MCI

indicator and linked to a higher risk of progression

to AD (Kazui et al., 2017). Early detection of social

apathy could help delay or prevent severe cognitive

decline.

Traditional methods for assessing apathy, like

clinical interviews and paper-based questionnaires,

often struggle to capture real-life social engagement

and can introduce bias through subjective reporting.

Digital and gamified approaches offer a more inter-

active and objective alternative, allowing for scalable,

user-driven assessments without needing trained per-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3631-3458

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7579-5069

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4490-4485

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3098-5894

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8111-0409

sonnel. This improves accessibility and engagement,

leading to more accurate and ecologically valid re-

sults compared to traditional methods (Tong et al.,

2014).

In this work, we introduce ApathySEED (SErious

game for Early Detection), a novel serious game de-

veloped to assess social apathy in patients with MCI.

Serious games, designed for purposes beyond enter-

tainment, have gained traction in healthcare for diag-

nosis, rehabilitation, and cognitive training (Chessa

et al., 2024). Effective serious games in health-

care must integrate more than just biomedical con-

tent—they must also prioritize usability, accessibil-

ity, and aesthetic appeal to engage users, particularly

older adults (Khalili-Mahani et al., 2019).

The contributions of our study are multi-faceted.

First, ApathySEED provides an innovative alterna-

tive to paper-based assessments for social apathy in

MCI, with a design tailored for elderly users. A pi-

lot study demonstrated its effectiveness and correla-

tion with traditional tools, showcasing its potential

for reliable, complementary data. The game also en-

ables early detection, supporting timely interventions

to prevent further cognitive decline. Finally, its intu-

itive design and visually appealing elements enhance

user engagement, improving both the user experience

and the efficacy of cognitive evaluations in healthcare.

Bort, C. D., Hussain, R., Manera, V., Chessa, M. and Solar i, F.

A Serious Game for Early Detection and Assessment of Social Apathy: A Pilot Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0013119700003912

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 20th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications (VISIGRAPP 2025) - Volume 1: GRAPP, HUCAPP

and IVAPP, pages 543-550

ISBN: 978-989-758-728-3; ISSN: 2184-4321

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

543

2 RELATED WORKS

Currently, there are several tests available for screen-

ing MCI (Tsoi et al., 2015), with the choice of test

largely depending on various factors such as the ad-

ministering expert’s familiarity with the tool, time

constraints, or the test’s perceived accuracy. Despite

this variety, there is a notable lack of standardization

in terms of accepted tests and scoring criteria, which

can affect the reliability of the results.

Several tests specifically designed for MCI diag-

nosis, such as the Memory Alteration Test (M@T)

(Rami et al., 2007) and Montreal Cognitive Assess-

ment (MoCA) (Nasreddine et al., 2005), are widely

used in psycho-geriatric settings for initial cognitive

evaluations (Chen et al., 2021b). While they as-

sess broad cognitive domains, they require profes-

sional administration and may not fully capture spe-

cific deficits like social apathy.

Apathy often coexists with other clinical syn-

dromes, such as depression, fatigue, and anhedonia.

Recently, the diagnostic criteria for apathy in brain

disorders have been updated (Robert et al., 2018;

Miller et al., 2021). These new criteria refine the do-

mains of apathy, indicating that a reduction in goal-

directed activity can manifest in behavioral, cognitive,

emotional, or social dimensions. Furthermore, apathy

is also observed to varying degrees in healthy individ-

uals (Ang et al., 2017), making its assessment impor-

tant for early identification and prevention of future

cognitive decline.

Integrating information and communication tech-

nologies into medical evaluation can offer valuable

diagnostic insights (Zeghari et al., 2020). However,

developing serious games for users with cognitive

impairments is challenging, as it requires addressing

their needs, emotional responses, and overall com-

fort. Since most affected individuals are elderly and

may have limited technological familiarity, usability

adaptations and a well-designed interface are crucial

for maintaining focus and immersion (Chen et al.,

2021a).

Several serious games for MCI assessment have

been developed. Kitchen and Cooking (Manera et al.,

2015) evaluates planning, attention, and object recog-

nition through cooking tasks, tracking performance

over time to monitor cognitive decline. In (Chessa

et al., 2019), a non-immersive exergame and an im-

mersive VR environment were tested, showing strong

correlation with standard clinical tests. SynapseTo-

Life (Costa et al., 2017) assesses problem-solving

skills through virtual real-life scenarios, while Skil-

lLab (Pedersen et al., 2023) uses six mini-games to

assess cognitive abilities like reaction time and mem-

ory. Despite these advancements, there remains a sig-

nificant gap in games designed specifically to assess

apathy in MCI populations.

3 THE PROPOSED SERIOUS

GAME

The ApathySEED serious game for social apathy as-

sessment has been designed in alignment with the di-

agnostic criteria for apathy outlined by (Robert et al.,

2018), ensuring the game’s relevance for clinical eval-

uation. The game’s narrative centers on decision-

making within social contexts. Participants are scored

based on their choices, which are mapped to the ap-

athy dimensions specified in the updated diagnostic

criteria. Figure 1 illustrates the various elements of

the developed game, including the avatars, 3D envi-

ronments, and user interface.

3.1 Narrative/Storytelling

The development of the narrative was closely super-

vised by an expert in the field, who is among the

authors, ensuring that both the storyline and deci-

sion points are clinically relevant and effectively con-

tribute to the evaluation of apathy. The storyline was

designed as a linear structure to enhance immersion

and to provide a smooth and continuous progression.

This seamless flow supports accurate assessments by

reflecting the patient’s social engagement or detach-

ment through their decision-making. To accommo-

date older adults’ limited tech experience, a brief tu-

torial was incorporated at the beginning of the game

to introduce the game mechanics.

The narrative unfolds across three distinct scenar-

ios (see below) and involves three characters: the

protagonist, representing the player; the protagonist’s

neighbor; and the protagonist’s daughter. User deci-

sions guide the player through various narrative paths

that intertwine and diverge throughout the game, en-

suring a coherent evaluation regardless of the chosen

route.

3.1.1 First Scenario: Living Room

The narrative begins with the player relaxing at home

when the doorbell rings amidst heavy rainfall. Upon

opening the door, the player encounters their neigh-

bor, who is soaked and distressed. The neighbor ex-

plains they’ve forgotten their keys and asks to stay un-

til the storm passes or their spouse arrives. The evalu-

ation in this scene focuses on the player’s willingness

to let the neighbor in and engage in conversation.

HUCAPP 2025 - 9th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

544

Figure 1: Various elements of the ApathySEED game.

3.1.2 Second Scenario: Neighbor’s Garden

After the storm subsides, the neighbor, express-

ing gratitude for the hospitality extended, offers the

player fresh vegetables from their garden. This of-

fer leads to two potential narrative pathways: accept-

ing or declining the offer, which assesses the player’s

willingness to leave the house.

• Accepting the Offer. The scene transitions to the

neighbor’s garden, where a conversation ensues.

The player’s responses to the neighbor’s emotions

and life events are assessed, alongside their initia-

tive to participate in activities like helping with the

vegetable harvest. Afterwards, the player returns

home and receives a phone call from their daugh-

ter, who reminds them of a dinner reservation at

a restaurant. The decisions made during this call

set the stage for the third part of the narrative.

• Declining the Offer. The player remains in the

living room, resting, and receives a phone call

from their daughter, reminding them of the din-

ner reservation at the restaurant. On the way to

the restaurant, the player encounters the neigh-

bor again in their garden, leading to a conversa-

tion that follows a similar pattern to that of the

“accepting the offer” narrative pathway, providing

another opportunity for assessing social engage-

ment.

3.1.3 Third Scenario: Restaurant

The final scene takes place in a restaurant where the

daughter had made a reservation for dinner. In this

setting, the player and their daughter reconnect after a

period of separation. This conversation serves to eval-

uate the player’s interest in their daughter’s life and

concerns, as well as their willingness to discuss per-

sonal matters. This scene is used to assess emotional

engagement and social apathy, as it involves intimate

family interaction.

To conclude the narrative, the player returns home

and is presented with a final decision that summarizes

their overall experience and engagement throughout

the game.

3.2 Scoring System

The final narrative framework encompasses twenty

key decisions, each offering three distinct options.

Depending on the player’s choice, a scoring sys-

tem is applied, awarding 0, 1, or 2 points per deci-

sion, resulting in a maximum achievable score of 40

points. These decisions are structured within social

dimension of apathy outlined in the diagnostic crite-

ria (Robert et al., 2018). In particular, 6 decisions cor-

respond to the emotion subdomain, 6 to the initiative

subdomain, and 6 to the interest subdomain, while the

remaining 2 decisions are intentionally left ambigu-

ous. To ensure a focused and reliable evaluation, the

five most definitive decisions from each subdomain

were selected for scoring, with each subdomain car-

rying a maximum potential score of 10 points. Higher

scores indicate lower levels of social apathy, reflect-

ing greater emotional engagement, initiative, and in-

terest in social interactions, while lower scores sug-

gest higher levels of apathy.

A Serious Game for Early Detection and Assessment of Social Apathy: A Pilot Study

545

3.3 Game Design

The game’s style and interface were designed to en-

sure accessibility for older users while meeting the

game’s needs. A stylized approach was chosen,

blending cartoonish and realistic elements to leverage

the benefits of both styles (Korre, 2023) while user-

centered guidelines informed the creation of simpli-

fied, high-contrast interface elements for intuitive and

accessible navigation (Gerling et al., 2012).

Character design was developed using the Ready-

PlayerMe

1

platform. Each character was crafted with

specific aesthetic and color criteria in mind, ensur-

ing alignment with the narrative requirements of the

characters. Simultaneously, Blender

2

was utilized for

the development of various 3D scenarios, combin-

ing internally created materials and models with pre-

existing elements sourced from BlenderKit

3

, Sketch-

fab

4

, and the Unity Asset Store

5

.

The user interface design was inspired by visual

concepts commonly found in existing video games,

aiming to create an engaging 3D background. To en-

hance immersion and narrative flow, dialogue boxes

featuring character portraits were integrated. Graphic

elements were developed using Illustrator

6

and Pho-

toshop

7

, while Figma

8

facilitated the integration and

overall design of the user interfaces. The design pro-

cess involved selecting a color palette and typography

that aligned with established design guidelines.

The game was developed using the Unity

9

game

engine. Three distinct scenes were created, utilizing

Blender models imported in FBX format with textures

and UV maps. A lighting system combining real-time

and pre-computed techniques was implemented, us-

ing directional, spot, and point lights, along with sky-

boxes, to create an immersive atmosphere.

Game mechanics were managed with custom

scripts and the Fungus

10

tool to streamline interactive

storytelling. Cameras were strategically positioned to

support the narrative, and characters were animated

using Mixamo

11

animations and custom ones from

Blender. Sound, visual effects, and post-processing

techniques were added to enhance immersion.

1

https://readyplayer.me/

2

https://www.blender.org/

3

https://www.blenderkit.com/

4

https://sketchfab.com/

5

https://assetstore.unity.com/

6

https://www.adobe.com/products/illustrator.html

7

https://www.adobe.com/products/photoshop.html

8

https://www.figma.com/

9

https://unity.com/

10

https://fungusgames.com/

11

https://www.mixamo.com/

Figure 2 shows gameplay screenshots high-

lighting key user interactions, including dialogues,

decision-making, and the user interface. These im-

ages illustrate how players engage with the narrative

and make choices that assess social apathy by simu-

lating real-life interactions, reflecting their social ini-

tiative and emotional connection.

4 GAME VALIDATION

To prepare for clinical use, it was essential to eval-

uate the game’s effectiveness, usability, and overall

feasibility as a tool for assessing social apathy. This

validation process was necessary to ensure the game

not only aligns with clinical diagnostic standards but

also remains functional, engaging, and accessible for

diverse user groups.

Therefore, a pilot study was conducted aimed to

gather data on technical performance and user inter-

action, focusing on ease of use, narrative immersion,

and clarity in decision-making. The study also pro-

vided preliminary insights into the game’s potential

for detecting social apathy by simulating real-world

interactions. The user study was conducted after ap-

proval from the university ethics research committee

of the University of Genoa (n. 2024/59).

4.1 Study Participants

A total of 33 participants were recruited from the stu-

dents and researchers community. The overall demo-

graphics of the participants can be found in Table 1.

All participants were volunteers and received no com-

pensation.

Table 1: Demographics of the participants. Gaming and

serious games experience is self-rated out of 10.

Total Participants 33

Male Participants 18

Female Participants 15

Age 26 ± 8.2

Video Gaming Experience 6.4 ± 2.6

Serious Games Experience 4.2 ± 2.7

All participants were presumed to be healthy, as

the primary objective of this pilot study was to evalu-

ate the game’s usability, user experience, and general

acceptance, rather than to assess its diagnostic accu-

racy in clinical populations. This approach allowed

the study to focus on refining the game mechanics and

interface, ensuring that the design would be intuitive

and engaging for a broader audience, including indi-

viduals with cognitive impairments in future studies.

HUCAPP 2025 - 9th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

546

Figure 2: Examples of various dialogues and decision making scenarios from the game.

4.2 Experimental Procedure

The game was installed on an Android tablet, specifi-

cally the Samsung Galaxy Tab S7 FE, which features

a 12.4-inch display with a resolution of 2560x1600

and runs on Android 13. This device was selected for

its large screen and high resolution, which facilitated

a more immersive and accessible gaming experience.

The experiments were conducted in a controlled

room at our institute, designed to provide a neutral,

distraction-free environment conducive to consistent

testing conditions for all participants. Each session

lasted approximately 20 minutes.

Prior to commencing the study, participants re-

ceived a thorough briefing on the project’s objectives,

including the ethical handling and confidentiality of

their personal data. After reviewing this information,

participants voluntarily signed a consent form, con-

firming their willingness to take part in the study. The

participants were further informed of their right to

withdraw from the study at any time without prej-

udice. A thorough explanation of the experimental

tasks and procedures was also provided to them.

At the start of each session, participants com-

pleted a brief demographic questionnaire, which in-

cluded questions about their prior experience with

video games and serious games. They then engaged

with the ApathySEED game, navigating the narrative

and making decisions independently. Upon complet-

ing the game, participants were asked to complete

several post-interaction questionnaires, which served

to assess their experience and evaluate key aspects of

the game’s usability, workload, and alignment with

its apathy detection objectives. These questionnaires

included:

• System Usability Scale (SUS). The SUS

(Brooke, 1996) consists of 10 items, each rated

on a five-point Likert scale. It provides a global

usability score out of 100, reflecting the game’s

user-friendliness.

• NASA Task Load Index (NASA-TLX). The

NASA-TLX (Hart and Staveland, 1988) measures

perceived workload across six dimensions: men-

tal demand, physical demand, temporal demand,

performance, effort, and frustration. Participants

rated each dimension on a scale from 0 to 20. The

raw version of the questionnaire was used and the

scores are scaled out of 100.

• Apathy Motivation Index (AMI). The AMI

(Ang et al., 2017) evaluates apathy across three di-

mensions (behavioral, social, and emotional) us-

ing 18 items, rated from 0 to 4. A standardized

range from 0 to 4 is used, where 0 represents no

apathy, and 4 indicates high apathy levels for each

dimension as well as the total score.

Throughout the process, participants were encour-

aged to respond honestly and were given the oppor-

tunity to ask questions for clarification at any point,

ensuring they fully understood the tasks and question-

naires.

4.3 Data Analysis

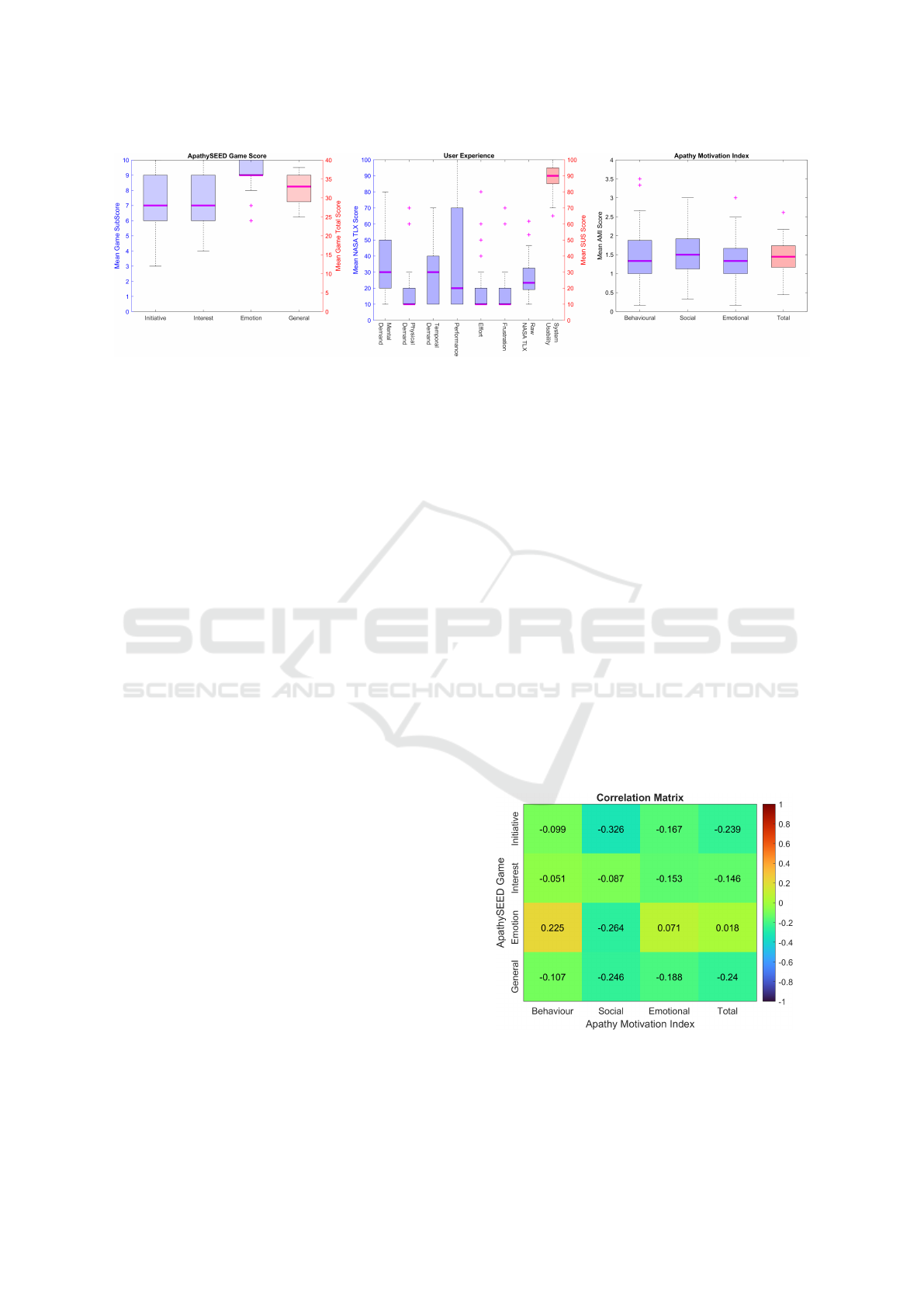

A boxplot for the mean game scores can be seen in

the left image in Figure 3. The mean scores (General:

32.58; Initiative: 7.55; Interest: 7.45; Emotion: 9.18)

suggest that participants displayed low levels of social

apathy, which aligns with expectations given that all

participants were presumably healthy individuals.

A Serious Game for Early Detection and Assessment of Social Apathy: A Pilot Study

547

Figure 3: Questionnaire responses. (left) ApathySEED game scores. (middle) User experience questionnaires, i.e., NASA

Task Load Index and System Usability Scale (rightmost column). (right) Apathy Motivation Index.

Among the subdomains, the emotion subdomain

exhibited both a higher mean score and a lower stan-

dard deviation compared to the interest and initia-

tive subdomains. This could imply that participants

demonstrated greater emotional responsiveness. Al-

ternatively, this result may reflect limitations in how

the emotional content of the game is currently framed,

as the narrative and decision-making process might be

influenced by socially acceptable norms rather than

authentic emotional engagement.

The middle image in Figure 3 illustrates partic-

ipants’ responses to the user experience question-

naires. In terms of system usability, low variability

was observed in participant responses, indicating a

general consensus regarding the ease of use and func-

tionality of the game. Users found the system in-

tuitive, accessible, and easy to learn, even without

prior experience, reflecting well on the design’s ef-

fectiveness. Most participants felt confident in using

the game, and the overall SUS score of 88.64 reflects

a strong perception of the system’s usability, though

some variation in individual user experiences was ob-

served.

Cognitive load responses showed low to moderate

variability, with the performance sub-scale exhibiting

the highest variability, indicating mixed perceptions

of success. The physical demand, effort, and frustra-

tion sub-scales were rated consistently low, suggest-

ing minimal strain. Mental and temporal demands

were seen as low to moderate, indicating some cog-

nitive challenge and time pressure, but not excessive.

The highest perceived workload was related to per-

formance, reflecting differing views on success. The

average NASA-TLX score of 26.16 suggests moder-

ate cognitive engagement without significant burden.

The right image in Figure 3 presents the scores for

the apathy questionnaire. The average scores across

the various dimensions (Behavioural: 1.49; Social:

1.53, Emotional: 1.39; Total: 1.47) are notably simi-

lar, suggesting that participants exhibited a generally

low level of apathy across all dimensions. This find-

ing aligns with expectations, given the healthy status

of the participants. Furthermore, the standard devia-

tions for each dimension demonstrate moderate vari-

ability in participants’ responses, which reinforces the

overall perception of low levels of apathy.

An analysis was conducted to explore the rela-

tionship between participants’ scores in the game

and their scores in the social dimension of the

AMI. The Shapiro-Wilk test revealed non-normal

data distribution(p < 0.05). Consequently, Spearman

correlation coefficients were computed to examine the

associations (see Figure 4). The results showed a neg-

ative trend due to inverse scoring scales. The initiative

dimension had the strongest correlation, highlighting

its reliability as an indicator of social apathy, while

the interest dimension showed the weakest correla-

tion. In general, the consistent trend across the AMI

scores mirrors the game scores, providing additional

validation for the effectiveness of the serious game in

assessing social apathy.

Figure 4: Spearman correlation coefficients between game

scores and AMI scores.

To further investigate this relationship, partici-

pants were divided into two groups based on their so-

HUCAPP 2025 - 9th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

548

cial apathy levels: low social apathy and high social

apathy. This classification facilitated a comparative

analysis of game performance in relation to the par-

ticipants’ social apathy levels. A cutoff of 1.5, corre-

sponding to the median AMI social dimension score,

was used, i.e., scores below 1.5 were categorized as

low, and scores above 1.5 as high. A Mann-Whitney

U-test assessed statistical differences between groups,

with results summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Mann-Whitney U-test.

Statistics p-value

Initiative 76.5 0.038

Interest 110.0 0.405

Emotion 86.5 0.070

General 93.5 0.153

The comparison between the low and high social

apathy groups revealed no statistically significant dif-

ferences in the general score or in the dimension of

interest, indicating a lack of clear distinction between

the groups in these areas. Although the dimension of

emotion did not achieve statistical significance, the p-

value was close to the conventional threshold of 0.05,

suggesting a potential trend towards a difference be-

tween the groups. Notably, the dimension of initiative

displayed statistically significant differences between

the groups. This suggests that variations in partici-

pants’ willingness to take initiative in social situations

are closely associated with their levels of social apa-

thy, making this dimension a valuable focus for future

assessments and interventions.

4.4 Discussion

This pilot study aimed to evaluate the usability and

effectiveness of the ApathySEED serious game in as-

sessing social apathy. The high SUS score suggests

that participants found the game user-friendly and in-

tuitive, meeting the design goal of easy adoption for a

wide audience, including potential clinical users. The

NASA-TLX results reflected a low to moderate cog-

nitive load, indicating the game was challenging yet

manageable for participants, with minimal frustration

or physical demand.

The game scores were consistent with AMI

scores, reflecting similar patterns across self-reported

and game-based measures. The game scores indi-

cated low levels of apathy among healthy partici-

pants, reinforcing the game’s validity as an apathy as-

sessment tool. The initiative subdomain, in particu-

lar, demonstrated the strongest correlation with AMI

scores, suggesting that this aspect of the game aligns

well with traditional measures of social apathy. This

dimension also revealed statistically significant differ-

ences between participants with low and high social

apathy, underscoring its sensitivity in detecting vary-

ing levels of initiative in social contexts.

Although the study yielded promising results, sev-

eral limitations should be acknowledged. First, the

sample consisted exclusively of healthy participants,

limiting the generalizability of the findings to clini-

cal populations with cognitive impairments or apathy-

related disorders. Future studies will involve patients

with known apathy or cognitive impairment to evalu-

ate the game’s effectiveness in a more clinically rele-

vant context.

Moreover, the emotional domain of the developed

game showed potential for improvement, as the cur-

rent narrative may not fully engage or evaluate emo-

tional apathy as intended. Revisiting the design and

content of the emotional scenarios could enhance the

game’s ability to assess this dimension more accu-

rately.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This work introduced ApathySEED, a serious game

designed for the assessment of social apathy, particu-

larly targeting individuals with cognitive impairment.

The game design focused on simulating decision-

making in social contexts to evaluate apathy across

various dimensions by paying attention to the effec-

tiveness and easiness of interactions. A pilot user

study was conducted with 33 healthy participants to

evaluate the game’s validity, usability, and cognitive

demand using standardized tools such as the SUS,

NASA-TLX, and AMI questionnaires. The findings

show the game’s potential as an effective tool for as-

sessing apathy, with promising usability and low cog-

nitive load. Future work will expand the study to clin-

ical environments, involving patients with mild cog-

nitive impairment to further validate the game’s effec-

tiveness in clinical settings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The work was supported by the Interreg Alcotra

project INTEVIDI (n. 20178). The authors would

like to thank all the volunteers who took part in the

user study.

A Serious Game for Early Detection and Assessment of Social Apathy: A Pilot Study

549

REFERENCES

Ang, Y.-S., Lockwood, P., Apps, M. A., Muhammed, K.,

and Husain, M. (2017). Distinct subtypes of apathy

revealed by the apathy motivation index. PloS one,

12(1):e0169938.

Brooke, J. (1996). SUS - a quick and dirty usability scale.

Usability evaluation in industry, 189(194):4–7.

Chen, Y.-T., Hou, C.-J., Derek, N., Huang, S.-B., Huang,

M.-W., and Wang, Y.-Y. (2021a). Evaluation of the re-

action time and accuracy rate in normal subjects, mci,

and dementia using serious games. Applied Sciences,

11(2):628.

Chen, Y.-X., Liang, N., Li, X.-L., Yang, S.-H., Wang, Y.-

P., and Shi, N.-N. (2021b). Diagnosis and treatment

for mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review of

clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements.

Frontiers in Neurology, 12:719849.

Chessa, M., Bassano, C., Gusai, E., Martis, A. E., and

Solari, F. (2019). Human-computer interaction ap-

proaches for the assessment and the practice of the

cognitive capabilities of elderly people. In Leal-Taix

´

e,

L. and Roth, S., editors, Computer Vision – ECCV

2018 Workshops, pages 66–81, Cham. Springer Inter-

national Publishing.

Chessa, M., Gerini, L., Hussain, R., Martini, M., Pizzo,

M., Solari, F., and Viola, E. (2024). Extended reality

and artificial intelligence for exergaming: Opportuni-

ties and open challenges for rehabilitation and cogni-

tive training. In 2024 IEEE 8th Forum on Research

and Technologies for Society and Industry Innovation

(RTSI), pages 357–362.

Costa, J., Neto, J., Alves, R., Escudeiro, P., and Escudeiro,

N. (2017). Neurocognitive stimulation game: Seri-

ous game for neurocognitive stimulation and assess-

ment. In Serious Games, Interaction and Simulation:

6th International Conference, SGAMES 2016, Porto,

Portugal, June 16-17, 2016, Revised Selected Papers

6, pages 74–81. Springer.

Etgen, T., Sander, D., Bickel, H., and F

¨

orstl, H. (2011).

Mild cognitive impairment and dementia: the impor-

tance of modifiable risk factors. Deutsches

¨

Arzteblatt

International, 108(44):743.

Gerling, K. M., Schulte, F. P., Smeddinck, J., and Ma-

such, M. (2012). Game design for older adults: ef-

fects of age-related changes on structural elements

of digital games. In 11th International Conference

on Entertainment Computing (ICEC), pages 235–242.

Springer.

Hart, S. G. and Staveland, L. E. (1988). Development

of NASA-TLX (task load index): Results of empiri-

cal and theoretical research. In Hancock, P. A. and

Meshkati, N., editors, Human Mental Workload, vol-

ume 52 of Advances in Psychology, pages 139–183.

North-Holland.

Kazui, H., Takahashi, R., Yamamoto, Y., Yoshiyama, K.,

Kanemoto, H., Suzuki, Y., Sato, S., Azuma, S., Sue-

hiro, T., Shimosegawa, E., et al. (2017). Neural

basis of apathy in patients with amnestic mild cog-

nitive impairment. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease,

55(4):1403–1416.

Khalili-Mahani, N., De Schutter, B., et al. (2019). Affec-

tive game planning for health applications: quanti-

tative extension of gerontoludic design based on the

appraisal theory of stress and coping. JMIR serious

games, 7(2):e13303.

Korre, D. (2023). Comparing photorealistic and animated

embodied conversational agents in serious games: An

empirical study on user experience. In International

Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, pages

317–335. Springer.

Manera, V., Petit, P.-D., Derreumaux, A., Orvieto, I., Ro-

magnoli, M., Lyttle, G., David, R., and Robert, P. H.

(2015). ‘kitchen and cooking,’a serious game for mild

cognitive impairment and alzheimer’s disease: a pilot

study. Frontiers in aging neuroscience, 7:24.

Miller, D. S., Robert, P., Ereshefsky, L., Adler, L., Bateman,

D., Cummings, J., DeKosky, S. T., Fischer, C. E., Hu-

sain, M., Ismail, Z., et al. (2021). Diagnostic criteria

for apathy in neurocognitive disorders. Alzheimer’s &

Dementia, 17(12):1892–1904.

Nasreddine, Z. S., Phillips, N. A., B

´

edirian, V., Charbon-

neau, S., Whitehead, V., Collin, I., Cummings, J. L.,

and Chertkow, H. (2005). The montreal cognitive as-

sessment, moca: a brief screening tool for mild cogni-

tive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics

Society, 53(4):695–699.

Pedersen, M. K., D

´

ıaz, C. M. C., Wang, Q. J., Alba-

Marrugo, M. A., Amidi, A., Basaiawmoit, R. V.,

Bergenholtz, C., Christiansen, M. H., Gajdacz, M.,

Hertwig, R., et al. (2023). Measuring cognitive

abilities in the wild: Validating a population-scale

game-based cognitive assessment. Cognitive Science,

47(6):e13308.

Rami, L., Molinuevo, J. L., Sanchez-Valle, R., Bosch, B.,

and Villar, A. (2007). Screening for amnestic mild

cognitive impairment and early alzheimer’s disease

with m@ t (memory alteration test) in the primary care

population. International Journal of Geriatric Psychi-

atry: A journal of the psychiatry of late life and allied

sciences, 22(4):294–304.

Robert, P., Lanct

ˆ

ot, K., Ag

¨

uera-Ortiz, L., Aalten, P., Bre-

mond, F., Defrancesco, M., Hanon, C., David, R.,

Dubois, B., Dujardin, K., et al. (2018). Is it time to

revise the diagnostic criteria for apathy in brain disor-

ders? the 2018 international consensus group. Euro-

pean Psychiatry, 54:71–76.

Tong, T., Chignell, M., Lam, P., Tierney, M. C., and Lee,

J. (2014). Designing serious games for cognitive as-

sessment of the elderly. In Proceedings of the Interna-

tional Symposium on Human Factors and Ergonomics

in Health Care, volume 3, pages 28–35. Sage Publi-

cations Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA.

Tsoi, K. K., Chan, J. Y., Hirai, H. W., Wong, S. Y., and

Kwok, T. C. (2015). Cognitive tests to detect demen-

tia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA in-

ternal medicine, 175(9):1450–1458.

Zeghari, R., Manera, V., Fabre, R., Guerchouche, R., K

¨

onig,

A., Phan Tran, M. K., and Robert, P. (2020). The “in-

terest game”: A ludic application to improve apathy

assessment in patients with neurocognitive disorders.

Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 74(2):669–677.

HUCAPP 2025 - 9th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

550