Analysing Online Communities for Health Promotion:

Characteristics of Digital Platforms Supporting Physical Activity

Jennifer Hachiya

a

Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, The Open University, Milton Keynes, England

Keywords: Digital Platforms, Physical Activity, Health Communities, Health Promotion, Behavior Change Techniques.

Abstract: The objective of this study was to analyse existing digital platform (DP) characteristics of online communities

(OC) to promote physical activity (PA). Previously DP identified in our previous scoping review were

matched against our inclusion criteria. DP were included if mainly used to promote PA and were free of

access. In addition to the general attributes of each DP, data was retrieved on user engagement strategies,

BCT, and platform credibility. A total of 50 DP were found in our Google search. Fourteen OC from the

Google search and 3 OC from our previous scoping review (n=17) were included in this study. Most DP (13;

64.70%) use an activity tracker—either external or internal—to support users on PA self-monitoring, almost

all DP (16; 94.12%) included GPS connectivity features, and about half of selected DP (9; 52.94%) had a

forum for community interaction. We found references to 26 (92.86%) of the 28 strategies used for analysis.

While research on OC to promote PA and DP characteristics has been growing, existing DP does not provide

detailed information on its attributes, nor comprehensive, specific data on engagement strategies and BCT.

1 INTRODUCTION

While digital platforms (DP) have gained significant

attention in recent years for promoting physical

activity (PA), online communities (OC) within these

platforms provide a dynamic and cost-effective way

to engage wider audiences. Moreover, the features of

DP that host OC play a critical role in determining the

extent and duration of user engagement, which

directly influences the success of these communities

in increasing members’ PA levels (Manzoor et al.,

2016; Resnick et al., 2010).

User engagement encompasses participation

dynamics and collaboration within online

environments, where individuals can interact, express

themselves, and challenge their personal goals and

mental models. Strategies to promote engagement in

DP are varied and can include storytelling, calls-to-

action, involving celebrities, using emotionally-

triggering content, photos of program-related

activities, collaboration with users for post imagery,

or user-tagging in posts (Andrade et al., 2018);

exclusive access to registered users (Ba & Wang,

2013); dashboard personalisation (Boratto et al.,

2017); open-ended questions to users, rewards for

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1991-6580

posting, responsive DP manager communication, or

facilitating self-introductions between users and DP

managers (Richardson et al., 2010); prohibition of

commercial messages, no toleration for disrespectful

language, enforcement of organised, fragmented

discussions, or DP conversation thread style adapted

to public audience (Lopez-Gonzalez et al., 2014);

comment section, user reaction in posts, consistent

forum content postings, prearranged 3-5 weekly

tasks, or interactive podcast content (Mailey et al.,

2019); or reward users for showing skills and

expertise, notifications, custom usernames, custom

avatar, in-person meetings, consent of privacy limits,

or possibility to open camera directly in the DP

(Malinen & Ojala, 2011).

In addition to strategies aiming to keep the user

engaged with the OC hosted in a specific DP, there is

a need to also consider the use of behaviour change

techniques (BCT) as the aim is to promote PA, i.e., to

change behaviour. BCT are observable and repeatable

elements of behaviour change interventions that,

when employed alone or in combination, can

contribute to behaviour change (Abraham & Michie,

2008; Cane et al., 2015). The relevance of BCT

originates from their value in raising collaborative

Hachiya, J.

Analysing Digital Platforms and Online Communities for Promoting Physical Activity.

DOI: 10.5220/0013121500003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 2: HEALTHINF, pages 433-440

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

433

responsiveness to change behaviour (Lopez-

Gonzalez et al., 2014).

There are two indicators in BCT that studies have

acknowledged so far—the relevance of the number of

BCT to apply, and the importance of self-regulation

strategies (Bondaronek et al., 2018).

Existing reports do not provide thorough

discussions on BCT or user engagement strategies. In

fact, when it comes to deciding what type of content

to share in OC to promote PA, and what user

engagement strategies to use, a set of guidelines is yet

to be established. This explains the pertinence of

exploring characteristics of PA-related OC’s

supporting DP.

However, despite the potential benefits of using

OC in DP and the importance of DP characteristics to

support OC in promoting PA, specific barriers must

be overcome. One of the most critical ones is the

long-term maintenance of user engagement (Kolt et

al., 2020; Tague et al., 2014; Toscos et al., 2010).

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our main research question is: “What are the main

characteristics of DP aiming to promote PA?”. This

question was operationalized in specific research

questions:

1) What are the attributes of these DP?

2) Which BCT are currently used in these DP?

3) What strategies are implemented to keep

user engagement in these DP?

4) How credible are these DP?

2.1 Identification of Relevant DP

First, we checked if the DP identified in our previous

scoping review (Hachiya, 2023) met this study’s

inclusion and exclusion criteria. Additionally, we

used Google's related searches (i.e., ''People also

searched for'') to find additional DP related to the

promotion of PA. The search was performed on

December 16th, 2021.

The website search results from Google search

were exported into Microsoft Excel (Microsoft,

16.56) and duplicates were removed. DP were

screened against inclusion criteria by one author and

discrepancies were discussed with a second reviewer.

DP were included if they supported an OC that: is

used mainly to promote PA; targets the general

public; is free of access or has a free version available.

DP were excluded if they: mention PA but its main

aim is not to promote PA; are used exclusively for

research purposes; are in other languages besides

English, Portuguese, French and/or Spanish; and are

no longer active or currently under development.

2.2 Data Collection

In addition to the general attributes of each DP (Table

1, Appendix A), data was retrieved on user

engagement strategies, BCT, and platform credibility.

The first two DP were analysed by the author and two

reviewers and results were discussed to clarify doubts

and fine-tune the methodology.

To be able to collect the necessary data, the author

registered in the DP as a regular user. To analyse

more specific elements of the DP—such as activity

upload options, activity interactions among users, the

existence of leaderboards, GPS connectivity, activity

import features, number of PA available, and types of

PA available—we created specific activities and

uploaded them in the DP. For this, we used the

Garmin Vivoactive 4S, an activity tracker with

Global Positioning System (GPS), then performed

and recorded two different activities: an approximate

1 km walk and two 60-minute dance classes. These

activities were uploaded in each DP which allowed

for the upload of data regarding PA.

When DP were available in multiple formats,

desktop websites were prioritised in this analysis due

to their broad advantages over apps. In DP in which

the app format is the only option for analysis, we

downloaded and evaluated the app using a mobile

device with iOS. In cases where DP have both a free

and a premium version, we only evaluated the free

version. We based all data on the information

available in each DP after login.

To gather missing or outdated DP attribute

information, we contacted each DP through their

contact email or the help form. All table categories

were identified with corresponding DP attributes.

When the information could not be determined, the

attributes were labelled as inconclusive.

2.3 Data Analysis and Reporting

We checked the app download page or desktop

website to find data such as DP support, type, device

compatibility, languages available, registered

category, subscription type, subscription fee and

other DP history information (i.e., year of inception,

partner accounts). The extracted information can be

found in Table 1 (Appendix A).

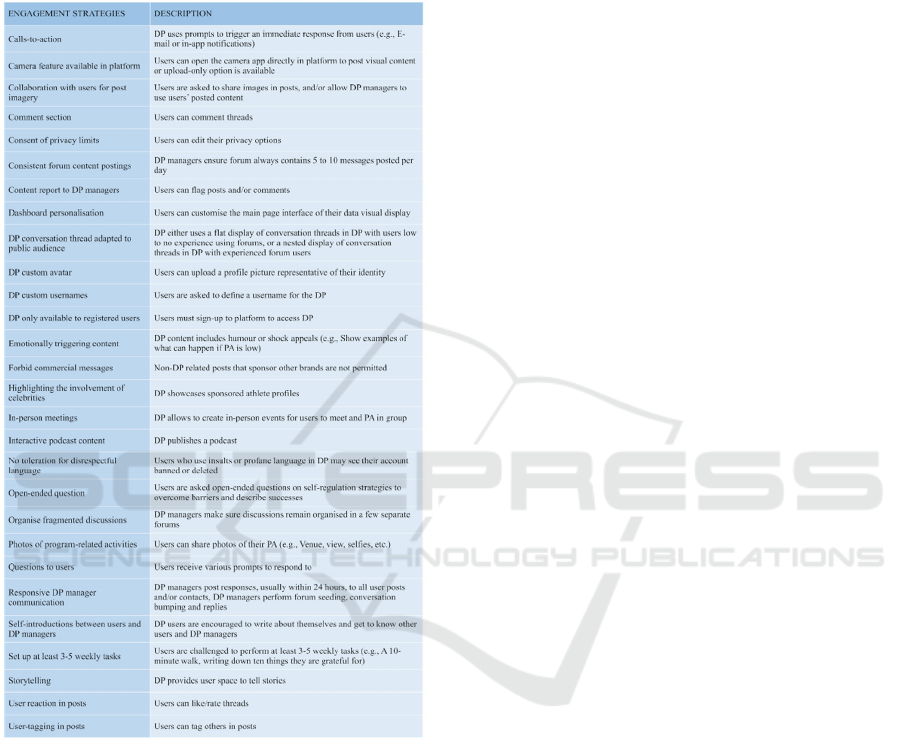

User engagement strategies were characterised

against the 28 specific actions detailed in Table 2 and

were developed based on the work of several authors

(Andrade et al., 2018; Ba & Wang, 2013; Boratto et

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

434

al., 2017; Kolt et al., 2020; Lopez-Gonzalez et al.,

2014; Mailey et al., 2019; Malinen, 2015; Resnick et

al., 2010; Richardson et al., 2010).

Table 2: List of 28 actions related to user engagement strat-

egies.

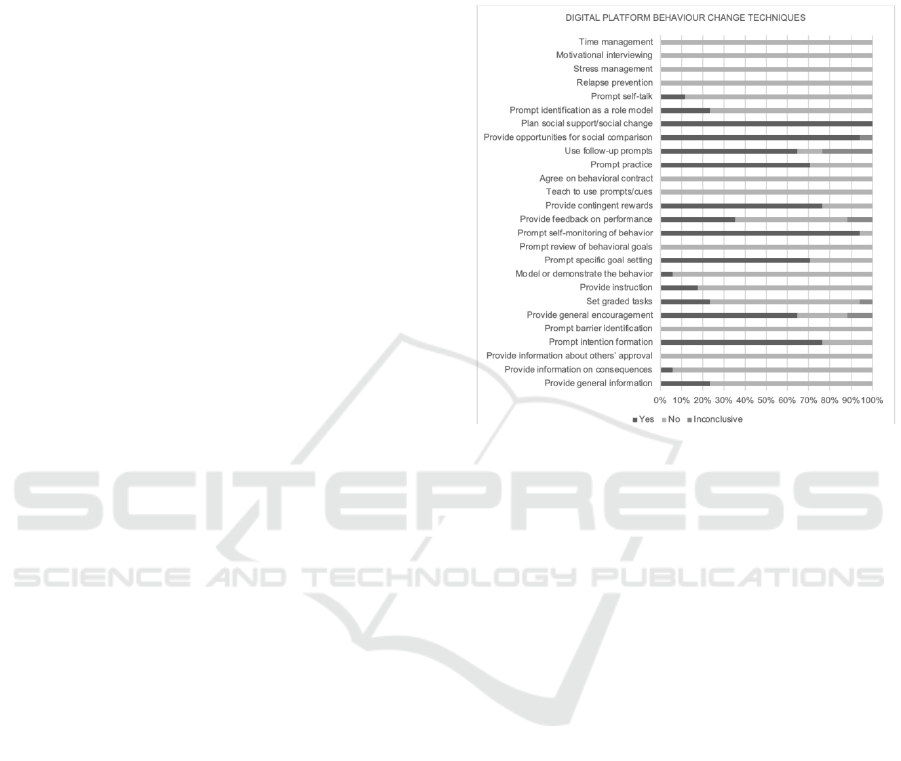

BCT were matched against the BCT Taxonomy

developed by Abraham and Michie (2008), which

includes 40 hierarchically clustered BCT that were

categorised as being present or absent. The BCT

Taxonomy can be found in Table 3 (Appendix A).

To analyse DP credibility, we collected the shared

content sources, the existence of monitoring of shared

information within these DP, and contribution and/or

content quality check from specialists associated with

the shared information (e.g., contribution of health

professionals). We classified 17 documental quality

indicators as present or absent using Bagrichevsky

and Vasconcellos-Silva's (2019) Checklist (see Table

4, Appendix A). However, as there was not enough

DP data for a full evaluation, five indicators—contact

validity (10), usability (14), certification (15),

conflicts of interest (16), and objectivity (17)—were

not assessed. Nevertheless, we evaluated the key

aspects of digital platform usability, including

authorship, link coherence, help accessibility, and

information management options.

Finally, we coded each option individually as

being present or absent and performed a quantitative

analysis method of frequencies for all research

questions. Moreover, we also used the DP number of

users to perform a cross-tabulation analysis.

3 RESULTS

After checking the 22 DP identified in our previous

study against the current study inclusion and

exclusion criteria, 18 were excluded because they

were no longer active (n=4), were used exclusively

for research purposes (n=7), we were unable to find

them (n=3), were in language outside of the inclusion

criteria scope (n=1), promoting PA was not its main

aim (n=1), required paid membership (n=1), and were

still under development (n=1). Details on each

excluded DP can be found in Table 5 (Appendix A).

Only three DP from our scoping review were

included in the current study: Movescount, Strava,

and RunKeeper. Details on each included DP can be

found in Table 6 (Appendix A).

In the Google search, we found 24 DP in searches

related to the Movescount DP, 18 related to the

RunKeeper and 21 related to Strava. Of these 63 DP,

13 were repeated, and 50 DP were checked against

inclusion and exclusion criteria. To explore the

details. The full results for ''People also searched for''

related searches can be accessed in Table 7

(Appendix A).

After checking each 50 of the DP against the

inclusion and exclusion criteria, 30 were excluded

because they mentioned PA, but their main aim was

not to promote PA, 2 were DP with paid

memberships, and 2 because they were not a DP (1

was a PA log-only app, and 1 was a running plan in

podcast format). Consequently, 14 DP from the

Google search and 3 DP from the scoping review

(n=17) were included in this study for further

analysis. For more details on this, see Table 8

(Appendix A).

3.1 Existent DP Attributes

Only 9 (52.94%) of 17 DP have a specific forum for

the community to interact and/or ask community

support questions. Of the 17 selected DP, none were

supported in website-only format, 6 (35.29%) DP

Analysing Digital Platforms and Online Communities for Promoting Physical Activity

435

were supported in app-only format and 11 DP were

supported in both website and app format. Most DP

(13; 64.70%) use an activity tracker—either external

or internal—to support users on PA self-monitoring,

almost all DP (16 out of 17; 94.12%) included GPS

connectivity features and roughly half of selected DP

(9 out of 17; 52.94%) had a forum within their OC for

users to interact with each other—either by accessing

and sharing their own PA or to request peer-to-peer

user support. When it comes to DP subscription types,

5 (29.41%) were completely available free of access

and 12 (70.59%) comprised two versions—a free and

a premium one.

On what refers to language availability of DP,

Garmin Connect TM took over with 35 languages.

That is almost double the number of languages

available in the second DP with the most language

availability, Sports Tracker (n=19). As for the DP

with the least number of languages available, there

were two: Charity Miles and Zombies, Run!, which

were only available in English. The data frequency of

language availability is presented in Table 9

(Appendix A).

Regarding the number of PA types available in

the DP, both Garmin Connect TM (n=95) and Sports

Tracker (n=91) take the lead with a significantly

greater amount of PA available than their

counterparts. The DP with the least number of PA are

RunKeeper, Strava, Adidas Running App Run

Tracker, Nike Run Club, Map My Run by Under

Armour, Map My Ride GPS Cycling Riding, and

Fitbit with only one PA type available. Data on the

number of PA types available in each DP, the current

number of users in DP and the year of launch are

presented in Table 10 (Appendix A).

3.2 Behaviour Change Techniques in

DP

We found reference to at least one BCT in the 17

selected DP. Only one BCT was reported in all 17 DP

(i.e., Plan social support or social change).

The most reported BCT (with a reporting

frequency between 50 and 100%) were: prompt

intention formation, provide general encouragement,

prompt specific goal setting, prompt self-monitoring

of behaviour, provide contingent rewards, prompt

practice, and use follow-up prompts.

Nine BCT were not reported at all in any of the

DP considered: provide information about others'

approval, prompt barrier identification, prompt

review of behavioural goals, teach to use

prompts/cues, agree on behavioural contract, relapse

prevention, stress management, motivational

interviewing, and time management. Table 12

presents the BCT and their respective frequency of

reporting in the selected DP.

Table 12: Presence of BCT.

3.3 User Engagement Strategies

We found references to 26 (92.86%) of the 28

strategies used for analysis. The two user engagement

strategies “Set up at least 3-5 weekly tasks” and

“consistent forum content postings” were not found

at all. Table 13 presents the 28 actions related to user

engagement strategies and their respective frequency

of reporting in the selected DP.

The most reported actions related to user

engagement (with a reporting frequency between 50

and 100%) were: photos of program-related activities,

DP only available to registered users, forbid

commercial messages, no toleration for disrespectful

language, DP conversation thread adapted to public

audience, calls-to-action, comment section, user

reaction in posts, DP custom avatar, and consent of

privacy limits.

The least reported actions related to user

engagement (with a reporting frequency between 0

and 49%) were: storytelling, highlighting the

involvement of celebrities, in-person meetings,

organise fragmented discussions, responsive DP

manager communication, questions to users,

emotionally triggering content, open-ended

questions, self-introductions between users and DP

managers, interactive podcast content, collaboration

with users for post imagery, user-tagging in posts,

camera feature available in the platform, DP custom

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

436

usernames, dashboard personalization, and content

report to DP managers.

Table 13: Frequency of user engagement strategies.

3.4 DP Credibility

We found reference to at least one indicator in the 17

selected DP of the 12 indicators present in our

adapted version of Bagrichevsky and Vasconcellos-

Silva’s (2019) checklist.

The most reported indicators (with a reporting

frequency between 50 and 100%) were: authorship,

coherence of the title and the content, dates of creation

and web publication, links, coherence of links, the

existence of contact details, help, information

management, and navigability. The least reported

indicators (with a reporting frequency between 0 and

49%) were: promoting body, endorsement, and date of

update. To access details regarding the respective

frequency of credibility indicators found in the selected

DP, see Table 14 (Appendix A).

4 DISCUSSION

This DP analysis aimed to characterise selected DP,

according to our inclusion and exclusion criteria, by

identifying the main attributes in DP, finding which

BCT are present in these DP, what type of user

engagement strategies can be detected and how

credible are DP.

Considering the increase of DP launches over the

last years, results suggest that the number of

successful DP have been increasing. Most DP are

supported by both website and app formats, available

in a reasonable number of languages, accommodating

a reduced amount of PA types, and a significant

amount of DP with both free and premium versions.

When evaluating BCT, DP appeared to include

the necessary components for PA promotion success

(Kolt et al., 2020; Mailey et al., 2019), whereas when

evaluating user engagement techniques in DP, we

identified low reports on consistency, active

engagement, and personalisation actions. Finally,

Presence of DP credibility indicators appear

considerable, validating the selected DP in the study.

4.1 Overview of DP Attributes

It was interesting that of so many DP, only roughly

50% had a specific forum and/or a feature for users to

request support. Especially considering the

importance of interaction and social support in PA

(World Health Organization, 2020) and how specific

forums and community power enhance a sense of

community and social responsibility (Kalgotra et al.,

2021; Romeo et al., 2019).

Considering the number of DP available only in

app format and the benefits of using a website and app

(Gordon & Crouch, 2019), DP might benefit from

being supported in both formats simultaneously. This

could increase user opportunities to access DP, thus

increasing DP resources and dependability, which has

previously been reported as a barrier to users’

consistency in OC interaction (Kolt et al., 2020;

Mailey et al., 2019; Tague et al., 2014).

The fact that roughly 30% of analysed DP are

completely free of access was quite impressive,

however, the fact that 70% of DP comprises two

versions, can also be rather beneficial. Complete free

access might widen user access, however, when a

service is paid, it also heightens the commitment the

user must make to the DP responsibility (Kalgotra et

al., 2021; Romeo et al., 2019), hence possibly

increasing accountability and discipline for frequent

and/or long-term usage—which has been reported

(Kolt et al., 2020; Tague et al., 2014). as one of the

main problems in user engagement maintenance.

Language variety might also tell a lot about a

DP’s overall success (Bondaronek et al., 2018;

Preece, 2001). Although of the 17 selected DP, 6 DP

Analysing Digital Platforms and Online Communities for Promoting Physical Activity

437

included 15 or more languages, it is significant that

11 DP were available in less than 15 languages. This

presented a noteworthy discrepancy between the DP

with the highest number of available languages (n =

35) and the DP with the least languages available (n

= 1). This might explain DP shortage of PA

promotion effectiveness and user engagement

success and interfere with a thorough, accurate

analysis. That is, some DP might still be under

development and, therefore still lack expected

resources.

However, a deeper analysis must be done to

understand what makes DP have limited language

availability. A few reasons for this might be that:

users are not accessing the DP in other countries in

which the languages are not available nor requesting

specific language accessibility besides English, and

language diversity in DP is not being reported as a

determining factor for usage (Bondaronek et al.,

2018), or DP are not interested in expanding the

number of users, or prioritising localization.

In terms of available PA types in DP, the

discrepancy between the ones with more and fewer

types of PA is considerable. With this, we can more

easily presume that PA-related DP can mostly be

divided into two categories: DP that are pervasive,

and DP that choose to specialise in a certain PA type.

This could be correlated with the fact that DP with

more PA types available has their own PA tracking

device—which makes it even more complete.

4.2 Behaviour Change Techniques

Studies have shown the importance of BCT’s

presence in DP, especially when there is a specific

goal to change health behaviours. Accordingly, in this

case, we aimed to understand which BCT were being

applied in OC. Included studies report on 17 of the 26

BCT described by Abraham and Michie (2008).

Although it is noteworthy to mention that BCT

such as planning social support or social change have

been identified in all analysed DP, other likewise

relevant BCT were not found at all (i.e., teach to use

prompts/cues, time management, and stress

management), or infrequently reported (i.e., provide

instruction, and model or demonstrate the behaviour).

This is significant because difficulty in navigating

through DP due to a lack of resources and

dependability is frequently reported as a problem in

DP long-term success (Kolt et al., 2020; Tague et al.,

2014) and, also, as a user barrier to lack of

consistency when using a DP (Mailey et al., 2019;

Rose et al., 2018; Toscos et al., 2010).

Additionally, prompting users to perform barrier

identification, another one of the BCT that was not

present in any of the DP might refrain DP from

gaining more insight on what can be done to promote

PA more efficiently (Mailey et al., 2019; Rose et al.,

2018).

As many studies agree, self-motivation is an

important factor in building on intrinsic motivation

(Edney et al., 2017). This might explain previous

reports on the low effectiveness of digital

interventions to promote PA (Greene et al., 2013;

Mailey et al., 2019) which simultaneously mention

digital interventions as possibly successful in

influencing behavioural change (Manzoor et al.,

2016; Richardson et al., 2010).

Additionally, we found that BCT related to

prompting users to perform specific actions (i.e.,

prompt intention formation, prompt specific goal

setting, prompt self-monitoring of behaviour, prompt

practice, and use follow-up prompts) were among the

most reported BCT.

However, we also found that DP fails to give

enough attention to actions that directly relate to trigger

user accountability in DP engagement through

information sharing (Parker et al., 2021), such as:

providing general information and providing

information on consequences (for not performing a

specific activity) and, especially, providing feedback

on performance. This might explain low DP

effectiveness since, as previous studies have reported,

receiving external positive encouragement in tasks

might motivate users to perform that action more

(Boratto et al., 2017; Mitchell et al., 2018), which

might ultimately help DP contribute to influencing PA.

4.3 Strategies to Engage Users in DP

The integration of user engagement strategies is

fundamental to exploring DP effectiveness in

promoting PA and creating an engaging environment

that will encourage user retention in the DP (Lopez-

Gonzalez et al., 2014; Tague et al., 2014). This

ongoing gap in guideline availability might influence

the recurrent mention of difficulty in lengthening

long-term engagement in DP (Edney et al., 2017;

Manzoor et al., 2016; Tague et al., 2014).

Overall, DP seems to cover important actions in

fundamental healthy community guidelines (i.e.,

forbid commercial messages, no toleration for

disrespectful language, DP conversation thread

adapted to public audience, calls-to-action, comment

section, user reaction in posts, DP custom avatar, and

consent of privacy limits).

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

438

However, actions associated with strategies

linked to consistency and active engagement were

either not reported (i.e., Set up at least 3-5 weekly

tasks, consistent forum content postings), or among

the least reported ones (i.e., responsive DP manager

communication, storytelling, questions to users,

open-ended questions, self-introductions between

users and DP managers, user-tagging in posts, and

content report to DP managers). This is problematic

since consistency in content posting and engagement

are some of the most important factors in digital user

retention because of their importance in building a

sense of community (Lopez-Gonzalez et al., 2014;

Mailey et al., 2019; Tague et al., 2014).

Also, given that personalisation in the digital world

is a factor that contributes to user immersion in a

specific digital environment (O’Brien & Toms, 2008),

the low report on actions related to it (i.e., collaboration

with post imagery, self-introductions between users

and DP managers, interactive podcast content, camera

feature available, DP custom usernames, dashboard

personalization), might be a contributing factor for

decreasing engagement over time.

The fact that engagement strategies are not

specifically strategised with validated models seems

to be one of the greatest problems found in this DP

analysis. This ongoing gap in guideline availability

might influence the recurrent mention of difficulty in

lengthening long-term engagement in DP (Edney et

al., 2017; Manzoor et al., 2016; Tague et al., 2014).

4.4 Credibility in DP

As for the credibility of DP, according to our adapted

version of Bagrichevsky and Vasconcellos-Silva’s

(2019) checklist, DP seem to have included most of the

indicators thoroughly, with the relevant indicators

being highly present in most of the DP. The investment

of DP in indicators associated with community

engagement is quite positive (Kalgotra et al., 2021).

The fact that endorsement and promoting body

are among the least reported might be a positive

indicator when it comes to DP credibility. It might

show that DP are reluctant to use famous personalities

and/or institutions as leverage to uphold credibility

and motivate PA as the use of public figures can

create inadequate dependability to sustain behaviour

change. Nevertheless, associating with specific

promoting bodies connected to governmental health

initiatives might also help validate the DP regulation

and value towards current and potentially new users

(Bagrichevsky & Vasconcellos-Silva, 2019), making

it a more trustworthy community for users to rely on

long-term (Kolt et al., 2020).

5 LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE

DIRECTIONS

Although we strived for a comprehensive search

procedure, only the free versions of DP were

examined, thus it is possible that we did not capture

the full range of engagement strategies used. The

categorisation of user engagement strategies was

based on the author's expertise rather than verified

models, which were non-existent. Direct studies of

long-term user participation and engagement would

provide more detailed insights. Additional research

into app downloads, platform formats, and user

engagement patterns over time, including usage

frequency, is needed.

Furthermore, investigating correlations between

PA types, language availability, launch dates,

updates, user numbers, and monitoring devices may

shed light on their impact on DP characteristics, BCT,

engagement strategies, and credibility indicators.

Addressing factors such as privacy concerns and

market competition, which limit data disclosure, may

contribute to further research in this field.

6 CONCLUSION

Existing research and DP for promoting PA lack

detailed information about their characteristics, user

engagement strategies, and BCT. While progress has

been made in understanding the function of OC in

promoting PA, there are still substantial gaps in user

engagement and long-term retention. Future research,

including extensive case analyses, is required to assess

the efficacy of various strategies and techniques,

ensuring that platforms are better suited for retaining

user engagement and promoting behavioural change.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is supported by Fundação para a Ciência e

Tecnologia (FCT) under the PhD grant

SFRH/BD/144296/2019.

REFERENCES

Abraham, C., & Michie, S. (2008). A taxonomy of behavior

change techniques used in interventions. Health Psy-

chology, 27(3), 379–387.

Andrade, E. L., Evans, W. D., Barrett, N., Edberg, M. C.,

& Cleary, S. D. (2018). Strategies to increase Latino

Analysing Digital Platforms and Online Communities for Promoting Physical Activity

439

immigrant youth engagement in health promotion using

social media: Mixed-methods study. JMIR Public

Health and Surveillance, 4(4), e71.

Ba, S., & Wang, L. (2013). Digital health communities: The

effect of their motivation mechanisms. Decision Sup-

port Systems, 55(4), 941–947.

Bagrichevsky, M., & Vasconcellos-Silva, P. R. (2019).

Documental quality of websites concerning physical

activity, lifestyle and sedentarism available on the in-

ternet. Health, 11(12), 1684–1692.

Bondaronek, P., Alkhaldi, G., Slee, A., Hamilton, F. L., &

Murray, E. (2018). Quality of publicly available physi-

cal activity apps: Review and content analysis. JMIR

mHealth and uHealth, 6(3), e53.

Boratto, L., Carta, S., Fenu, G., Manca, M., Mulas, F., &

Pilloni, P. (2017). The role of social interaction on us-

ers’ motivation to exercise: A persuasive web frame-

work to enhance the self-management of a healthy life-

style. Pervasive and Mobile Computing, 36, 98–114.

Edney, S., Plotnikoff, R., Vandelanotte, C., Olds, T., De

Bourdeaudhuij, I., Ryan, J., & Maher, C. (2017). “Ac-

tive Team”: A social and gamified app-based physical

activity intervention. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 1–10.

Gordon, N. P., & Crouch, E. (2019). Digital information

technology use and patient preferences for internet-

based health education modalities: Cross-sectional sur-

vey study of middle-aged and older adults with chronic

health conditions. JMIR Aging, 2(1), e12243.

Greene, J., Sacks, R., Piniewski, B., Kil, D., & Hahn, J. S.

(2013). The impact of an online social network with

wireless monitoring devices on physical activity and

weight loss. Journal of Primary Care & Community

Health, 4(3), 189–194.

Hachiya, J. (2023). Scoping review on online communities

to promote physical activity. In Online communities as

a tool to promote physical activity (p. 44). [Doctoral

thesis, Universidade de Aveiro]. CDU:

004.7:613.98(043)

Kalgotra, P., Gupta, A., & Sharda, R. (2021). Pandemic in-

formation support lifecycle: Evidence from the evolu-

tion of mobile apps during COVID-19. Journal of Busi-

ness Research, 134, 540–559.

Kolt, G. S., Duncan, M. J., Vandelanotte, C., Rosenkranz,

R. R., Maeder, A. J., Savage, T. N., ... & Mummery, W.

K. (2020). Successes and challenges of an IT-based

health behaviour change program to increase physical

activity. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics,

268, 31–43.

Lopez-Gonzalez, H., Guerrero-Solé, F., & Larrea, O.

(2014). Community building in the digital age: Dynam-

ics of online sports discussion. Communication and So-

ciety, 27(3), 83–105.

Mailey, E. L., Irwin, B. C., Joyce, J. M., & Hsu, W.-W.

(2019). Independent but not alone: A web-based inter-

vention to promote physical and mental health among

military spouses. Applied Psychology: Health and

Well-Being, 11(3), 562–583.

Malinen, S., & Ojala, J. (2011). Applying the heuristic eval-

uation method in the evaluation of social aspects of an

exercise community. In Proceedings of the DPPI’11

Conference (pp. 23–31). New York, NY: ACM.

Manzoor, A., Mollee, J. S., Araújo, E. F. M., Van Halteren,

A. T., & Klein, M. C. A. (2016). Online sharing of

physical activity: Does it accelerate the impact of a

health promotion program? In Proceedings of the 2016

IEEE International Conferences on Big Data and Cloud

Computing (pp. 201–208). IEEE.

O’Brien, H. L., & Toms, E. G. (2008). What is user engage-

ment? A conceptual framework for defining user en-

gagement with technology. Journal of the American So-

ciety for Information Science and Technology, 59(6),

938–955.

Parker, K., Uddin, R., Ridgers, N. D., Brown, H., Veitch,

J., Salmon, J., Timperio, A., Sahlqvist, S., Cassar, S.,

Toffoletti, K., Maddison, R., & Arundell, L. (2021).

The use of digital platforms for adults’ and adolescents’

physical activity during the COVID-19 pandemic (Our

Life at Home): Survey study. Journal of Medical Inter-

net Research, 23(2), e23615.

Resnick, P. J., Janney, A. W., Buis, L. R., & Richardson, C.

R. (2010). Adding an online community to an internet-

mediated walking program. Part 2: Strategies for en-

couraging community participation. Journal of Medical

Internet Research, 12(4), e72.

Richardson, C. R., Buis, L. R., Janney, A. W., Goodrich, D.

E., Sen, A., Hess, M. L., ... & Piette, J. D. (2010). An

online community improves adherence in an internet-

mediated walking program. Journal of Medical Internet

Research, 12(4), e71.

Tague, R., Maeder, A. J., Vandelanotte, C., Kolt, G. S.,

Caperchione, C. M., Rosenkranz, R. R., ... & Mum-

mery, W. K. (2014). Assessing user engagement in a

health promotion website using social network-

ing. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics,

206, 84–92.

Toscos, T., Consolvo, S., & McDonald, D. W. (2010). “...is

it normal to be this sore?”: Using an online forum to

investigate barriers to physical activity. In Proceedings

of the 1st ACM International Health Informatics Sym-

posium (pp. 346–355). New York, NY: ACM.

World Health Organization. (2020). WHO guidelines on

physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Geneva:

World Health Organization.

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

440