A Vector Autoregression Model for Depicting the Relation Between

Labour Market Economic Indicators and Real Wages in the United

States Manufacturing Sector

Ishaan Kshirsagar

1 a

, Julian M

´

arquez Simon

2 b

, Nicol

`

o Sch

¨

atz

3 c

, David Fraga Gonz

´

alez

3 d

and Conor Ryan

4,5 e

1

Department of Arts and Sciences, University College London, London, U.K.

2

Department of Economics, University College London, U.K.

3

Department of Philosophy, University College London, U.K.

4

Department of Computer Science and Information Systems, Biocomputing and Developmental Systems Research Group,

University of Limerick, Ireland

5

Lero, The Science Foundation Ireland Research Centre for Software, Ireland

Keywords:

Vector Autoregression Model, Real Wages, Time Series Analysis, US Labour Market, Manufacturing Sector.

Abstract:

In recent years, the US manufacturing sector and its labour market dynamics have gained importance in the

face of resurgent protectionism and increased governmental strategic investment plans. Simultaneously, real

wage growth in the manufacturing sector has diverged compared to the wider economy. While studies have

previously analysed the relationship between labour market conditions and real wages in the wider economy,

few have specifically evaluated the manufacturing sector in this respect. To this end, we selected a comprehen-

sive list of economic indicators covering the key aspects of the sectoral labour market. Subsequently, a vector

autoregression (VAR) model was developed, enabling us to account for time lags and the interconnectedness

of each variable. In addition to this, graphs and plots were created to provide a visual understanding of the

database, results, and labour market dynamics. The findings of our model suggest that the economic consen-

sus on real wage determination in the wider economy also holds for the manufacturing sector. An important

exception to this is the strongly negative relationship between the inflation rate and real wages.

1 INTRODUCTION

This paper examines how labour market conditions

affect changes in real wages in the United States man-

ufacturing sector between the years 2000 – 2024.

To this end, a Vector Autoregression (VAR) model

was developed using a dataset compiled from vari-

ous U.S. government databases (Federal Reserve Eco-

nomic Data , ; ?). Moreover, tests were also con-

ducted to ensure the data complied with the necessary

conditions for VAR modelling.

The US manufacturing sector has recently gained

in political significance, as reshoring and tariffs have

become more frequent. While the share of overall em-

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0002-2700-9366

b

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-9481-5125

c

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-7974-0176

d

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-5008-5843

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7002-5815

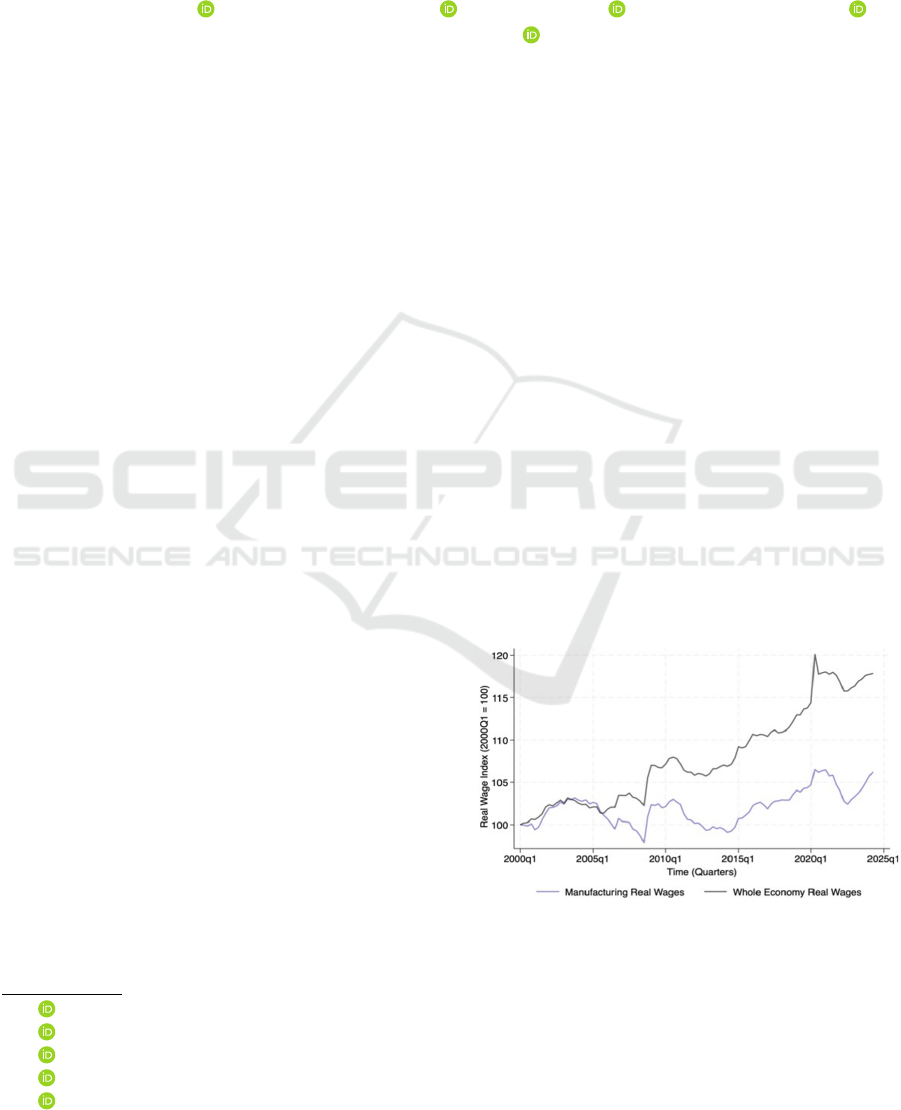

Figure 1: Time Series of Real Wages in the Manufacturing

Sector against Real Wages in the Whole Economy.

ployment in the manufacturing sector has fallen over

the recent decades, its share of GDP has remained

largely constant due to improvements in productiv-

ity (Baily and Bosworth, 2014). This means that the

manufacturing sector has broadly maintained its eco-

nomic relevance throughout this period.

296

Kshirsagar, I., Simon, J. M., Schätz, N., Fraga Gonzalez, D. and Ryan, C.

A Vector Autoregression Model for Depicting the Relation Between Labour Market Economic Indicators and Real Wages in the United States Manufacturing Sector.

DOI: 10.5220/0013123000003890

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART 2025) - Volume 3, pages 296-302

ISBN: 978-989-758-737-5; ISSN: 2184-433X

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

Figure 2: Time Series of Real Wages in the Manufacturing Sector against Real Wages in the Whole Economy.

Additionally, there has been a divergence between

real wages in the manufacturing sector and those

in the wider economy in recent decades (Figure 1).

These factors motivate a fresh analysis of wage de-

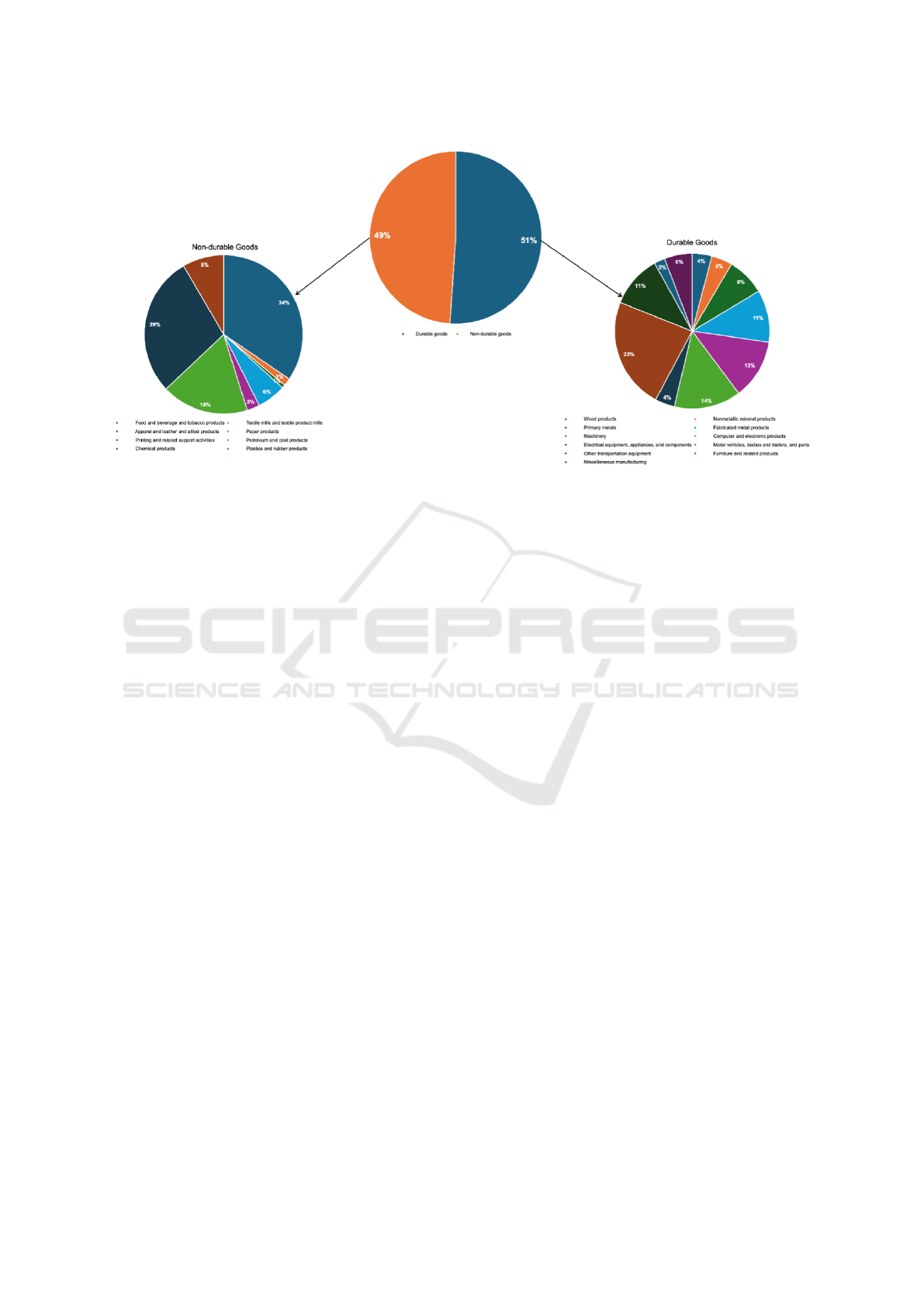

termination in the sector. Figure 2 provides insight

regarding the composition of the US manufacturing

sector. The industries shown are the subjects of anal-

ysis for this study.

The literary basis of our study will be further

expanded in Section 2. Section 3 will outline the

methodology, and the variables selected. Section 4

presents the results, visualisations and accompanying

economic discussions followed by the conclusions.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

The role of labour market variables as determinants

of real wages has been widely discussed in economic

literature. Domash and Summers (2022) utilised job

openings and unemployment rates as indicators of

slackness in the labour market, on the demand and

supply side respectively. To further measure demand

and supply side labour market forces, overtime hours

and industrial production are considered. On the other

hand, capacity utilisation has been employed by Stock

and Watson (2020) to capture real cyclical economic

activity.

A sectoral differentiation of wage determination

has been previously studied by Sheffield (2013). They

utilised a log-transformed linear regression model to

analyse the impact of sector-specific market variables

on real wage growth. The approach taken by Domash

and Summers (2022) relies on various wage Phillips

curve regressions at both the national and state levels

in the US.

Another statistical model that has been utilised to

analyse the effects of a variety of variables on real

wage growth in the past is VAR. Bernanke and Blin-

der (1992) employ a VAR model to determine the ef-

fects of monetary policy on real wages. Similarly,

Blanchard and Quah (1989) employ a structural VAR

to analyse the effects of demand and supply shock

on real wage growth. In both instances, analysis of

the relationship between their chosen macroeconomic

variables and real wage change. However, a VAR

analysis of the manufacturing sector in the US has,

to our knowledge, not been conducted before.

3 METHODOLOGY

This section describes the manufacturing sector’s

labour market variables for the study (Table 1). It also

provides the specifications of the VAR model and the

relevance of utilising VAR.

3.1 Dataset Details

This study uses a curated dataset utilising monthly

data from December 2000 to May 2024 collected

from the Bureau of Labour Statistics (BLS) (2024)

and the Board of Governors of the Federal Re-

serve System via the Federal Reserve Economic Data

(FRED) (2024) to analyse and examine the relation-

ship between real wage change and various labour

market economic indicators.

A Vector Autoregression Model for Depicting the Relation Between Labour Market Economic Indicators and Real Wages in the United

States Manufacturing Sector

297

Table 1: Description of Variables.

Variable Code Unit

Year-on-year Change in Real Average Hourly Earnings

of Production and Nonsupervisory Employees

RW Percentage (%)

Avg. Weekly Overtime Hours of Production

and Nonsupervisory Employees

WOH Hours

Unemployment Rate – Private Wage and Salary

Workers

UR Percentage (%)

Job Openings (First Differenced) JOB Rate

Real Sectoral Output for All Workers LP Index (January 2017 = 100)

Capacity Utilisation (NAICS) Rate CU Percentage (%)

Industrial Production (NAICS) IP Index (January 2017 = 100)

Year-on-year Change in the Consumer Price Index (CPI)

for All Urban Consumers: All Items in U.S. City

Average (First Differenced)

INF Percentage (%)

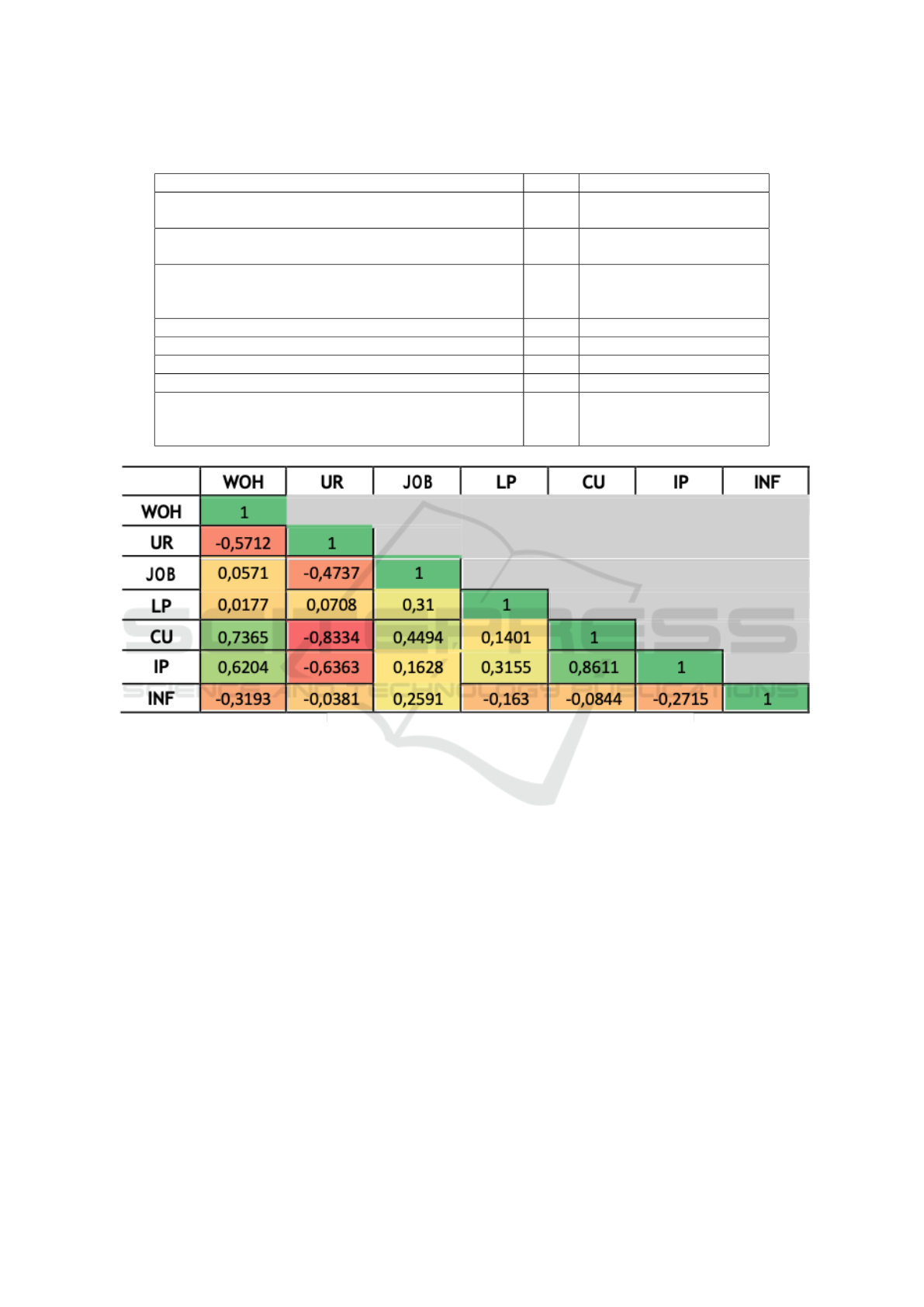

Figure 3: Correlation Matrix.

3.2 Vector Autoregression Model

This study employs a standard VAR model as pro-

posed by Breitung and Hamilton (2020) of the fol-

lowing form as defined in Equation 1:

Y

t

= c +

p

∑

i=1

φ

i

Y

t−i

+ ε

t

(1)

where:

Y

t

: The k × 1 vector of endogenous variables at time

t.

c: The k × 1 vector of constants.

φ

i

: The k × k matrix of coefficients for the i-th lag.

ε

t

: The k × 1 vector of error terms at time t.

p: The number of lags in the model.

VAR models are effective at capturing the inter-

connectedness and the interdependent relationships

among various variables. This is important consider-

ing the frequency of correlations in the dataset (Fig-

ure 3). VAR models enable an in- depth quantitative

time-series analysis, which would be particularly use-

ful to highlight the dynamic relationships among the

multiple labour market time series variables. A 24-

month lag was used to allow economic conditions to

fully reflect on wages. Similar lags were estimated by

Domash and Summers (2022).

Following the standard approach to VAR mod-

elling, we tested for linearity, stationarity, interdepen-

dence of variables, lack of co-integration and suffi-

ciently long time series. Our dataset contains monthly

data for just under 24 years and includes 282 data

points per variable, ensuring that the time-series is

sufficiently long. Furthermore, stationarity was tested

by conducting the ‘Augmented Dickey–Fuller unit-

root test’, which determined that both the job open-

ings rate and year-on-year inflation rate were non-

stationary. To remedy this, a first-differenced trans-

formation for these variables was undertaken, result-

ing in them becoming stationary. Moreover, the ‘Jo-

hansen test for cointegration’ and the ‘LM test for

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

298

Table 2: Regression Results with Lagged Variables.

Variable Lag Month Coefficient

Std.

Error

z-value p >z 95% Confidence Interval

Unemployment

Rate Sectoral

24 -0.0822 0.0317 -2.59 0.010 -1.4433 -0.02

Manufacturing Sector

Labour Productivity

24 0.1484 0.0447 3.32 0.001 0.0608 0.2359

Industrial

Production

24 1.2382 0.4125 3.00 0.003 0.4298 2.0466

(First Differenced)

Job Openings Rate

24 0.3116 0.0792 3.94 — 0.1565 0.4668

Average

Overtime Hours

24 -1.6491 0.2122 -7.77 0.000 -2.0649 -1.2332

YOY CPI

(First Difference)

1 -0.7148 0.0964 -7.42 0.000 -0.9036 -0.5259

Capacity

Utilisation Rate

24 -1.5795 0.5203 -3.04 0.002 -2.5992 -0.5597

residual autocorrelation’ were conducted to ensure

that there is no cointegration and no autocorrelation

among selected variables. In addition, the ‘Granger

causality test’ was conducted to check whether there

is Granger Causation between year-on-year (YOY)

change in real wages and the selected labour market

variables. The results of all the Granger causality tests

were significant, reflecting Granger causality between

changes in real wages and our selected labour market

indicators.

Additionally, we have employed a structural break

from November 2008 to October 2009 which covers

the period of volatility and instability during the fi-

nancial crisis and shields our model from parameter

instability at the time. The breakdown in the relation-

ship between labour market variables over this time

period, as evidenced by Michaillat and Saez (2019),

is further supported by our structural break testing us-

ing the algorithm proposed by Bai and Perron (1998,

2003).

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

The results from the vector autoregression are shown

in the following Equation 2:

RW = −1.65W OH −0.08UR+ 0.31 JOB+ 0.15 LP

− 1.58CU + 1.24 IP − 0.71 INF + 128.43 (2)

The coefficients above (Table 2) should be inter-

preted as follows: Unemployment rate sectoral indi-

cates that a change in the rate of 1 percentage point is

correlated with a fall of 0.0822 percentage points in

the YOY change in Real Wages in the manufacturing

sector after 24 months. The coefficients of the other

variables can be interpreted in a similar way. The co-

efficient of variables for which the first difference was

taken must be integrated upon interpretation. Figures

4 supplement the results by providing a more time

sensitive dissection of variable comovements across

the analysed period in the form of time series graphs

plotting explanatory variables against YOY change in

Real Wages.

This section will examine the results of the VAR

model using economic theory. According to classical

economic theory, real wage can be determined and af-

fected by various factors such as bargaining power, an

increase in demand for workers, productivity, an in-

crease in the cost of living and inflation, etc. The vari-

ables selected in the VAR model seek to cover these

wage-determining factors.

The negative relationship between the unemploy-

ment rate and real wages may be explained by a re-

duction in worker bargaining power caused by an in-

crease in unemployment. As increases in jobseekers

saturate the labour market, downward pressure is cre-

ated on real wages (Figure 5). Notwithstanding, our

model shows this negative relationship to be relatively

weak. A potential explanation is that workers who

have lost their jobs (and therefore their wages) are ex-

cluded from the average real wage calculation. If the

group of workers which has become unemployed had

lower wages than average, as was observed during the

covid-19 pandemic (Bateman and Ross, 2021), then

real wages would rise ceteris paribus. This may have

partly offset the decrease in real wages due to lower

worker bargaining power, making the coefficient for

the impact of the unemployment rate on real wage rel-

atively smaller than expected.

Similarly, an increase in real wages due to an in-

crease in job openings can be justified due to an in-

A Vector Autoregression Model for Depicting the Relation Between Labour Market Economic Indicators and Real Wages in the United

States Manufacturing Sector

299

Figure 4: Time series graphs of lagged indicators with structural breaks.

Figure 5: Effect of shift in demand for workers.

crease in demand for workers. Industrial production

follows the same trend, given that increasing output

tends to require an increase in workers operating at

a firm. This creates a higher demand for workers,

which increases their bargaining power and subse-

quently, their real wages. Figures 4c and 4f show that

this link looks to remain resilient during times of cri-

sis as can be seen in the coinciding shocks during the

COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 6: Effect of shift in demand for workers.

Another important factor that determines real

wages is inflation or cost of living. Real wages are de-

rived from the division of nominal wages by the infla-

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

300

tion rate, commonly measured by the CPI, as shown

below.

RealWageRate =

NominalWageRate

CPI

× 100 (3)

According to Equation 3, an increase in CPI leads

to a fall in real wages, ceteris paribus. The negative

CPI coefficient from our results implies that wages

have not kept up with inflation over the analysed pe-

riod. This phenomenon looks to be most apparent

during the period of high inflation volatility of the

early 2020s, which was mirrored by large swings in

the YOY change of real wages (as observed in Fig-

ure 4d). This indicates that US manufacturing sec-

tor labour markets struggle to keep pace in uncertain

inflationary environments. Further adding to the de-

pressive effect on real wages is that inflation generally

indicates economic instability, during which invest-

ments in the economy tend to fall as ROI (return on

investment) becomes more uncertain and difficult to

project.

Figure 7: Effect of shift in demand for workers.

The strong negative relationship between average

overtime hours and real wages evidenced by both the

results from the VAR and the synchronous movement

observed in Figure 4e, may be explained by work-

ers choosing to increase their overtime hours during

times of poor economic outlook and high cost of liv-

ing in an effort to maintain their living standards (Ci-

phr, 2023).

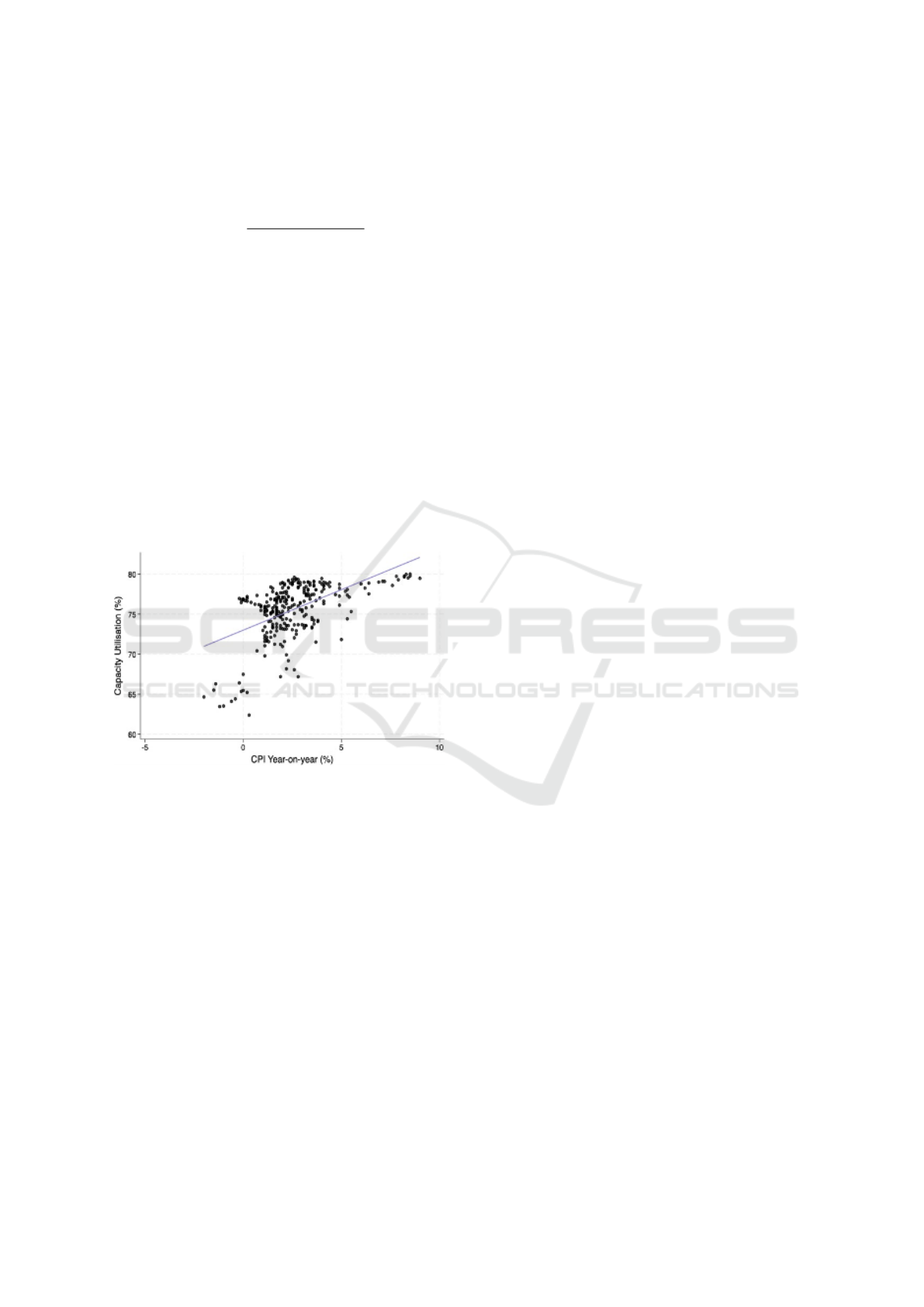

The strongly negative coefficient of capacity util-

isation follows orthodox Keynesian economic theory.

As the economy approaches full capacity, an increase

in aggregate demand leads to high inflationary pres-

sure and a decreasing marginal increase in real output

(represented in Figure 6). As previously discussed,

real wages tend to fall under higher inflation. Hence,

ceteris paribus, high-capacity utilisation creates infla-

tionary pressure in an economy, hence lowering real

wages as per Equation (3).

Empirically, the positive relationship between ca-

pacity utilisation and the inflation rate is shown by a

correlation coefficient of 0.42 (See Figure 7).

5 CONCLUSIONS

This research study shows that labour market eco-

nomic conditions are conducive to real wage changes

in the United States’ manufacturing sector between

the years 2000 and 2024.

The study found that the two main factors affect-

ing change in real wages are bargaining power and in-

flation. This is due to an increase in bargaining power

affecting a worker’s ability to negotiate a higher wage

ceteris paribus. In addition, inflation reduces the real

value of a worker’s nominal wage, hence having a sig-

nificant impact on their real wages. By developing a

comprehensive VAR model, this study has displayed

and quantified each lagged variables’ effect on YOY

change in real wages. The dataset and VAR model

results have been presented using a variety of visu-

alisation techniques, including time-series graphs, pie

charts, a scatter plot and heat map. The results are also

significant from a policy perspective. Inflation has

been shown to be highly corrosive to real wages in the

US manufacturing sector as labour markets have not

exhibited sufficient flexibility to absorb the effects.

While it is evident that policy makers ought to pri-

oritise inflation stabilisation, the results from average

overtime hours indicate that certain contractionary fis-

cal policies may not be effective in periods of eco-

nomic overheating. For example, income taxation

would not efficiently reduce aggregate demand (a key

factor in the reduction of inflation) as the results sug-

gest workers prefer to increase working hours rather

than decreasing personal consumption.

The approach taken in this paper could be ex-

panded to include other sectors or countries in future

studies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Dr Monika Sosa Smatralova for her

valuable insights.

REFERENCES

Bai, J. and Perron, P. (1998). Estimating and testing linear

models with multiple structural changes. Economet-

rica, 66(1):47.

A Vector Autoregression Model for Depicting the Relation Between Labour Market Economic Indicators and Real Wages in the United

States Manufacturing Sector

301

Bai, J. and Perron, P. (2003). Computation and analysis of

multiple structural change models. Journal of Applied

Econometrics, 18(1):1–22.

Baily, M. N. and Bosworth, B. P. (2014). Us manufacturing:

Understanding its past and its potential future. Journal

of Economic Perspectives, 28(1):3–26.

Bateman, N. and Ross, M. (2021). The pandemic

hurt low-wage workers the most—and so

far, the recovery has helped them the least.

Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/

articles/\\the-pandemic-hurt-low-wage-workers\

\-the-most-and-so-far-the-recovery\

\-has-helped-them-the-least/.

Bernanke, B. S. and Blinder, A. S. (1992). The federal funds

rate and the channels of monetary transmission. The

American Economic Review, 82(4):901–921. [online].

Blanchard, O. J. and Quah, D. T. (1989). The dynamic ef-

fects of aggregate demand and supply disturbances.

The American Economic Review, 79(4):655–673.

Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1827924.

Breitung, J. and Hamilton, J. D. (2020). Time series analy-

sis. Contemporary Sociology, 24(2):271.

Ciphr (2023). Two in five employees are working

extra hours as cost-of-living crisis bites. Re-

trieved from https://www.ciphr.com/press-releases/

\\two-in-five-employees-are-working-extra\

\-hours-as-cost-of-living-crisis-bite/.

Domash, A. and Summers, L. (2022). A labor market view

on the risks of a u.s. hard landing.

Federal Reserve Economic Data . Federal reserve economic

data — fred — st. louis fed. https://fred.stlouisfed.org.

[Accessed 19-12-2024].

Michaillat, P. and Saez, E. (2019). Beveridgean unemploy-

ment gap. NBER Working Paper. https://www.nber.

org/papers/w26474.

Sheffield, J. (2013). Contending theories of wage determi-

nation: An intersectoral analysis of real wage growth

in the u.s. economy. Pursuit: The Journal of Un-

dergraduate Research at the University of Tennessee,

4(2):4.

Stock, J. H. and Watson, M. W. (2020). Slack and cycli-

cally sensitive inflation. Journal of Money, Credit and

Banking, 52(S2):393–428.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. U.s. bureau of labor Statis-

tics. https://www.bls.gov/. [Accessed 19-12-2024].

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

302