Quantifying the Role of Active Listening and Reassurance in Virtual

Health Coach Interactions

Hussain Ghulam

a

, Brian Keegan

b

and Robert Ross

c

ADAPT Centre / School of Computer Science, TU Dublin, Ireland

Keywords:

Conversational Agents, LLM, Health Care, Active Listening, Reassurance.

Abstract:

Conversational Agents have the potential to support healthcare through coaching exercise routines, but are

still lacking in demonstrating authentic social behaviours to support engagement. To this end, we present a

series of experiments that we conducted in order to investigate how automated health care coaches can be

more effective when their interaction style is tailored to demonstrate qualities associated with a good bedside

manner, namely active listening and reassurance. To test this, we first developed a dataset of 135 dialogue

excerpts from three distinct sources, i.e., original, handcrafted and LLMs, the latter two of which were tuned

to demonstrate specific types of comforting or reassuring language. Using this dataset, we conducted a study to

validate whether users perceive different levels of active listening and reassurance across sources. The results

of the study indicate that users can distinctly perceive the varying levels of stimuli across the three different

data sources and that LLMs in particular clearly demonstrate these properties. In an accompanying analysis,

the results showed that there is no notable influence of participant personality on perception, which we argue

reduces the barrier to successful system deployment.

1 INTRODUCTION

Setting exercise goals can positively affect both phys-

ical and mental health, as well as aid recovery and

postoperative care for various medical conditions

(Hallal et al., 2016). The use of conversational agents

(CAs) as intelligent tools to deliver interventions to

achieve exercise goals represents a novel and poten-

tially inclusive approach to broadening physical ac-

tivity. These CAs can, in principle, exhibit greater

adaptability and personalization to user needs and of-

fer personalized recommendations based on prefer-

ences, goals, and fitness levels to improve physical ac-

tivity (Beinema et al., 2021). Despite recent progress

in context-oriented conversation models, integrating

certain language types that are adaptive and engag-

ing remains a challenge, hindering their ability to pro-

vide responses that feel more human-like and exhibit

human level emotional intelligence (Ahmad et al.,

2022).

As a manifestation of demonstrated emotional in-

telligence, good bedside manner in healthcare settings

refers to how healthcare professionals interact with

their clients. Possessing a good bedside manner is

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-6256-5523

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7793-398X

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1449-1827

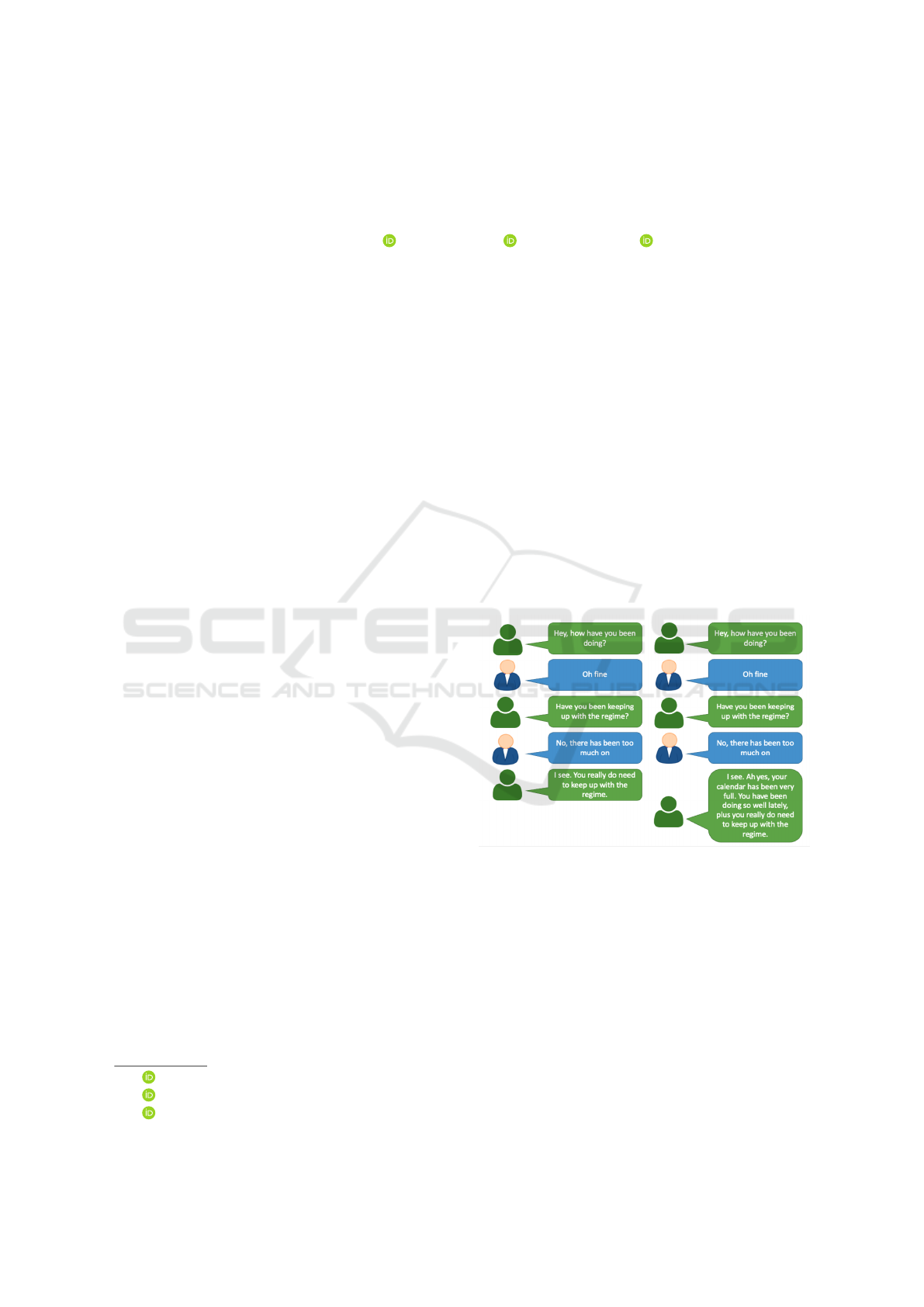

Figure 1: Contrasting Conversational Excerpts: Demon-

strating Presence and Absence of Active Listening and Re-

assurance Behaviors (Right) vs basic form (Left).

assumed to imply that clinicians and related health

professionals are kind, friendly, and understanding of

those in their care (Elliott, 2018). Good bedside man-

ner has been described as characterized by qualities

such as Active Listening and Reassurance (Berman

and Chutka, 2016). To illustrate, an example of two

contrasting interactions is shown in Figure 1. where

the interaction on the right-hand side demonstrates a

higher degree of encouragement, active listening, and

reassurance relative to the more basic form on the left.

Hussain, G., Keegan, B. and Ross, R.

Quantifying the Role of Active Listening and Reassurance in Virtual Health Coach Interactions.

DOI: 10.5220/0013124900003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 2: HEALTHINF, pages 449-457

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

449

Active Listening has been shown to make pa-

tients comfortable and alleviate their fears and anx-

ieties (Fassaert et al., 2007) while reassurance has

been shown to restore confidence, hope, and encour-

ages patients to pursue their goals (Rolfe and Burton,

2013). Despite significant studies that discuss and

emphasize the importance of active listening skills

and reassurance in healthcare education, there re-

mains a notable scarcity of studies that address active

listening and reassuring behaviour from the patient’s

perspective (Snyder, 2008).

In the context of conversational healthcare assis-

tants, the assumption prevails that CAs should display

many of the same qualities associated with a good

bedside manner, such as the ability to listen and com-

fort. However, it is far from clear whether CAs should

exhibit these qualities for all users during healthcare

communication, and indeed, it is much less clear how

these behaviors can and should be fine-tuned to the

user and conversational context.

Considering this, our research focuses on the de-

sign of adaptive-policy strategies (Sahijwani, 2022)

for a CA assisted health coaching system (Beinema

et al., 2023), which supports users in their health-

care goals by demonstrating suitable levels of active

listening and reassurance to the user. We are work-

ing specifically in the domain of exercise regime sup-

port, as this is applicable to a wide range of the pop-

ulation but has particular long-term benefits for the

medical community (Liang et al., 2021a). This pa-

per presents our work on an initial set of experiments

to validate the realization and user perception of be-

havioural variants in interaction to demonstrate the

ability to listen and reassure in typical coaching sce-

narios. The contribution of this work are as follows:

• The construction of a corpus of dialogue ex-

cerpts that demonstrate language types indicative

of active listening and reassuring language in the

health coaching domain.

• An evaluation of whether participants can identify

differences in language types controlled against

the source of that language and participant per-

sonality type.

2 BACKGROUND AND RELATED

WORK

Recently, CAs have been widely used in promoting

physical activity and improving health outcomes in

healthcare (Cohen Rodrigues et al., 2024). In such

cases, CAs provide patients with personalized guid-

ance and motivation to engage in physical activity,

track their progress, and provide feedback on their

performance. Additionally, CAs can be employed to

deliver educational resources to patients on the bene-

fits of physical activity and how to engage in it safely

and effectively (Cohen Rodrigues et al., 2024). It has

also been claimed that the use of CAs to promote

physical activity has the potential to improve overall

health outcomes, prevent chronic diseases, and reduce

healthcare costs (Moore et al., 2023). The existing

studies on the use of CAs in health and well-being

show that the field seems to be in its early stages of

development with some evidence of user acceptance

of CAs in the physical health domain (Wutz et al.,

2023). Despite the promising adoption of CAs in

healthcare, the research indicates a lack of human-like

effective communication and language types (Shan

et al., 2022).

Current health-centric CAs primarily focus on

users’ activity goals—meaning they concentrate on

coaching actions, mainly providing information re-

lated to regime prescription and physical assessment

with little work to date focusing on the social as-

pects of interaction management. However, the use of

social behaviours can help build strong relationships

and user engagement by incorporating different levels

of user personality aspects such as traits, persona and

language styles during communication (Fernau et al.,

2022). Indeed, CAs equipped with certain types of

language as indicators of empathetic language have

been found to play a central role in improving phys-

ical activity by helping people overcome anxiety or

concerns about physical activity (Lynch et al., 2022).

Additionally, such systems have been found to con-

tribute towards building and restoring confidence, fos-

tering a sense of care, and ensuring a feeling of calm.

This, in turn, alleviates doubts and enables people to

feel safe and valued in both clinical and non-clinical

settings (Hicks et al., 2014; Karlsson et al., 2012;

O’Keeffe et al., 2016).

Tuning to the specifics of Active Listening and

Reassurance: in early work Traeger et al. (2017), in-

dicated that reassurance is a notable psychological as-

pect related to good bedside manner which is very

important for various patient groups, including those

with long-term medical conditions and those under-

going pre- and post-treatment, as well as physical

therapy and counseling. Meanwhile, active listening

has been studied by Jagosh et al. (2011) as another

very crucial communicative behavior. This behavior

is valued not only in general communication, but also

in specialized health fields such as nursing, medicine,

health coaching, counseling, and rehabilitation (King,

2021). In the context of physical health, active listen-

ing enables the trainer to transition from being an ‘ex-

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

450

pert’ to a helpful guide. Instead of exerting pressure,

the trainer assumes the role of a supportive partner,

offering encouraging and reassuring communication

(

´

Olafsson et al., 2019). In active listening-focused

activities, such as counseling, occasional feedback

is essential to maintain a smooth flow of conversa-

tion. Feedback can be achieved by using supporting

backchannel (BC) cues, such as ‘Uh-huh’, ‘mm-hm’,

‘yeah’, ‘okay’ and ‘right’ (Ruede et al., 2017). BCs

serve as verbal and nonverbal indications of attention,

helping the listener to determine when it is their turn

to speak. The listener can incorporate BCs to express

their thoughts without interrupting the speaker (Lala

et al., 2017). There are two types of backchannels:

verbal backchannel, including responses like ‘mm-

hm’, ‘uhh-huh’ and ‘okay’, and nonverbal backchan-

nel, consisting of cues like nodding the head, mak-

ing eye contact, or laughing (Heinz, 1998). Research

indicates that the inclusion of backchannels can en-

hance user engagement and create a more natural con-

versation flow. Additionally, the backchannels con-

tribute to establishing a more positive relationship be-

tween the user and the conversational agent (Ding

et al., 2022).

3 EXPERIMENTAL GOALS AND

DESIGN

Given the lack of systematic investigation on this

topic to date, the present study seeks to investigate

methods to manipulate levels of reassurance and ac-

tive listening in CA output, and measure whether text

designed to demonstrate active listening and reassur-

ance was perceived as such by analyzing participant’s

perceptions of the provided texts. Our goal therefore

is to provide an approximate calibration of these qual-

ities and measurement of automatically versus manu-

ally collected data.

The experimental design of this study was struc-

tured into three elements:

In the first element, we measured the users’ per-

ception of different levels of active listening and reas-

surance across a corpus of dialogue excerpts sourced

from three distinct pools, i.e., original, handmade, and

LLM-generated content.

The second element of the study aimed to vali-

date whether participants can effectively discern dif-

ferences among language types while controlling for

variations in the source of language. The data sources

were further broken down into Block A (Active Lis-

tening), Block B (Reassurance) and Block C (Neutral)

within each language source.

In the third element of this study, we validated

whether different personality types have any differ-

ences in their perception of active listening and reas-

surance.

3.1 Data Synthesis and Properties

Given a lack of suitable existing data sets, we devel-

oped a dataset of dialogue excerpts clearly stating that

the coach is a conversational agent rather than a hu-

man. Specifically, we built a data set comprising 135

dialogues within the healthcare domain. The data set

has 45 dialogues sourced from original real world in-

teractions, 45 dialogues crafted by human annotators

(handcrafted), and an additional 45 dialogues gener-

ated using an LLM (LLM).

For the original dialogue data, we utilized an ex-

isting open-source dataset comprising human-human

dialogues in the context of physical healthcare coun-

seling to ensure the inclusion of real-world complex-

ities, clients concerns, and diverse language usage.

This data set was collected from a real world physical

activity intervention program for women (Liang et al.,

2021b). This original dialogue dataset was not classi-

fied in any way into active listening and reassurance

as this dataset was aimed to support social support for

physical activity and its barriers.

Building on this real world sourced dataset, hand-

made dialogues were curated with the help of anno-

tators to simulate various physical healthcare scenar-

ios, such as to incorporate a range of medical condi-

tions, and communication styles. For this work we

followed the guidelines and instructions discussed by

Wu et al. (2023). The curated dataset was distributed

proportionally across three blocks: 15 dialogues were

stylised or biased towards active listening, 15 towards

reassurance, and 15 featuring neutral language.

To generate automatic data, we used ChatGPT

3.5 with different prompts to create dialogue excerpts

in specific styles, depicting qualities related to ac-

tive listening and reassurance. The designed prompts

are provided in the appendix for reference. The

LLM-generated excerpts were distributed across three

blocks: 15 styled with active listening, 15 styled to-

wards reassurance, and 15 featuring neutral stimuli.

The data resources from this study are publicly avail-

able to promote further research on GitHub.

1

3.2 Study Design

After collecting the datasets, we conducted three sur-

veys – one for each data source – for dialogue eval-

uation. The surveys included a total of six questions,

1

The data resources are available on Github.

Quantifying the Role of Active Listening and Reassurance in Virtual Health Coach Interactions

451

specifically focused on examining the perception of

active listening and reassurance. The first three ques-

tions assessed active listening, while the remaining

three questions referred to reassurance. A 5-point

Likert scale was used to assess participant responses.

The participant ratings were calculated by averaging

the responses from each segment, reflecting perceived

levels of active listening and reassurance. These ques-

tions are included in the appendix for reference.

Nine dialogues were randomly displayed for each

user interaction. The evaluation system was deployed

on the Prolific crowd-sourcing platform (Eyal et al.,

2021) with informed consent. The time allotted to

each participant was 20 minutes. In total 90 partic-

ipants were recruited; 30 for each of the 3 language

sources, original, handmade, and LLM dialogues.

Following the stimuli rating activity, we asked

participants to rate themselves against the ten item

personality measure (TIPI) personality test (Gosling

et al., 2003) to assess the different personality lev-

els of participants. This supplementary assessment

aimed to validate whether different types of person-

ality have different trends regarding the perception of

active listening and reassurance. This measurement

results in an estimate of the openness, conscientious-

ness, extroversion, agreeableness, and emotional sta-

bility of the Big 5 personality traits demonstrated by

each participant.

3.3 Participant Demographics

In the first survey, which focused on data from origi-

nal dialogues, the cohort of 30 participants included

10 males, 17 females, and 3 participants who pre-

ferred not to disclose their gender. The ages of the

participants ranged from 22 to 67 years (M = 38.4,

SD = 5.63). The second survey, centered on hand-

made dialogues, included 14 men and 16 women in

the 30-participant cohort, with ages ranging from 23

to 73 years (M = 39.11, SD = 6.22). In the third sur-

vey with LLM-generated data, which also featured

30 participants, there were 12 men and 18 women,

and the age range was 27 to 55 years (M = 39.72,

SD = 6.16). Participants from the US, UK, Ireland,

New Zealand, and Australia were sourced across the

three studies. Analyzing the median time participants

spent engaging with the experiments reveals notable

patterns. The median time taken by participants in

survey I was approximately 17.68 minutes. Survey

II reveals that the median time taken by participants

was approximately 16.91 minutes. Survey III how-

ever stands out with a significantly shorter median

time of 9 minutes. The main cause of this shorter me-

dian time may be the ease of linguistic styles mim-

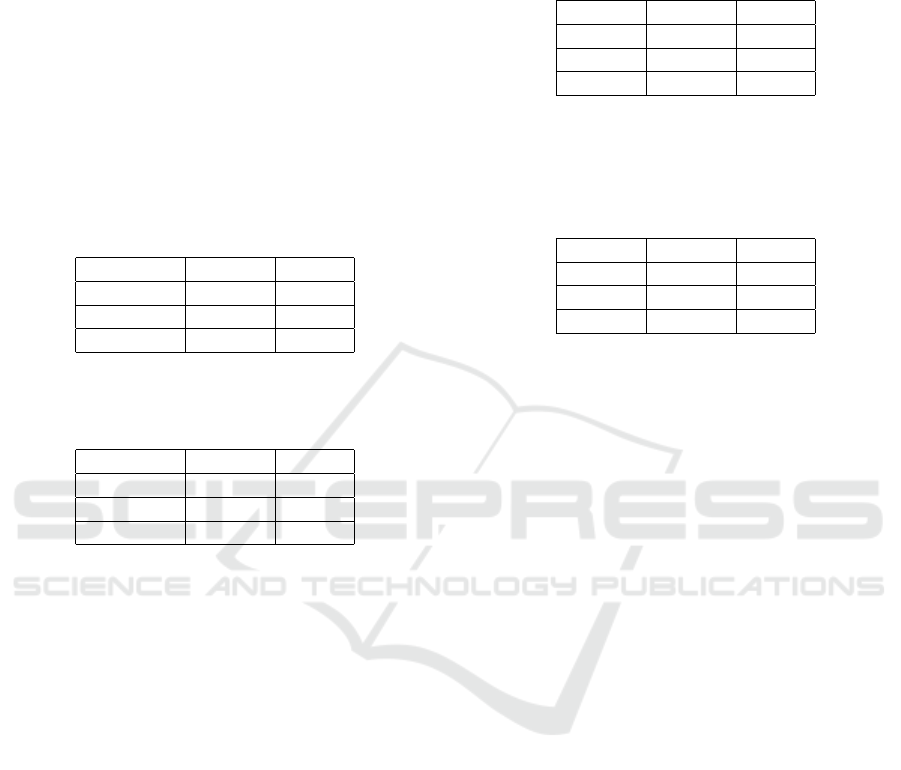

Figure 2: User’s Perception of Active Listening across Lan-

guage Sources (original, handmade, LLM).

Figure 3: User’s Perception of Reassurance across Lan-

guage Sources (original, handmade, LLM).

icked by LLMs, However, it can be in part be at-

tributed to average dialogue length. The mean lengths

of dialogues vary across data sources, with the dataset

of original dialogues having the longest dialogues

(mean length: 270.82 tokens), the handmade dataset

exhibiting moderate lengths (mean length: 215.59 to-

kens), LLM-generated dialogues feature the shortest

dialogues (mean length: 106.18 tokens).

4 EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS

In this section, we present the experimental results for

the three elements of the study.

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

452

4.1 Source Analysis

The first element investigates the perception of active

listening and reassurance across the three language

sources: original, handcrafted, and LLM-Generated

dialogues. Our goal here is to determine as a baseline

whether participants perceived any variation in over-

all amounts of reassurance and active listening across

the sources without taking into account any styling

blocks within those sources. Figures 2 and 3, illus-

trate the Likert scale ratings of perceived active lis-

tening and reassurance provided by the participants.

Table 1: Anova with post-hoc Tukey’s HSD Results for

Overall User’s Perception of Active Listening across the

data sources (original, handmade, LLM).

Group 1 Group 2 p-adj

Handmade LLM 0.9295

Handmade original 0.5448

LLM original 0.3347

Table 2: Anova with post-hoc Tukey’s HSD Results for

Overall User’s Perception of Reassurance across the data

sources (original, handmade, LLM).

Group 1 Group 2 p-adj

Handmade LLM 0.9437

Handmade original 0.3586

LLM original 0.5485

Overall, the results show that users perceive ac-

tive listening and reassurance slightly higher in both

the LLM and Handcrafted dialogues than in the base-

line original content. The perceived level is strongest

in LLMs. These results can be explained by the fact

that original content was not purposefully designed to

have reassurance and active listening qualities while

the other two text sources were designed (in part) to

display these styles. Statistical analysis by means of

the Anova with post-hoc Tukey’s HSD in Tables 1 and

2 shows that there are no statistically significant dif-

ferences in mean perception scores for ‘Active Lis-

tening’ and ‘Reassurance’ between any of the com-

pared language sources (‘Original’, ‘Handmade’, and

‘LLM-Generated’) and the adjusted p-value is also

recorded greater than the significance level. This in it-

self is also aligned with our experimental design since

not all dialogue examples within the LLM and hand-

crafted sets were stylised, thus resulting in a small and

notable though not strong perception effect.

4.2 Style Analysis

To dig deeper and account for the specific stylistic

biasing of the individual dialogues, the second ele-

Table 3: Anova with post-hoc Tukey’s HSD results for the

Perception of Active Listening Across the different blocks

of Handmade Data. Block A = Active Listening biased data;

Block B = Reassurance biased data, and Block C = Neutral

data.

Group 1 Group 2 p-adj

Block A Block B 0.6812

Block A Block C 0.7777

Block B Block C 0.9858

Table 4: Anova with post-hoc Tukey’s HSD results for the

Perception of Reassurance Across the different blocks of

Handmade Data. Block A = Active Listening biased data;

Block B = Reassurance biased data, and Block C = Neutral

data.

Group 1 Group 2 p-adj

Block A Block B 0.8019

Block A Block C 0.7262

Block B Block C 0.9907

ment of the investigation aimed to validate the partici-

pant ratings of active listening and reassurance against

the breakdown of the 45 dialogues distributed across

three distinctively styled blocks: Block A (Active

Listening biased data), Block B (Reassurance biased

data), and Block C (Neutral). We present results for

handmade dialogues and LLM dialogues but not orig-

inal content since no style biasing was applied for that

content.

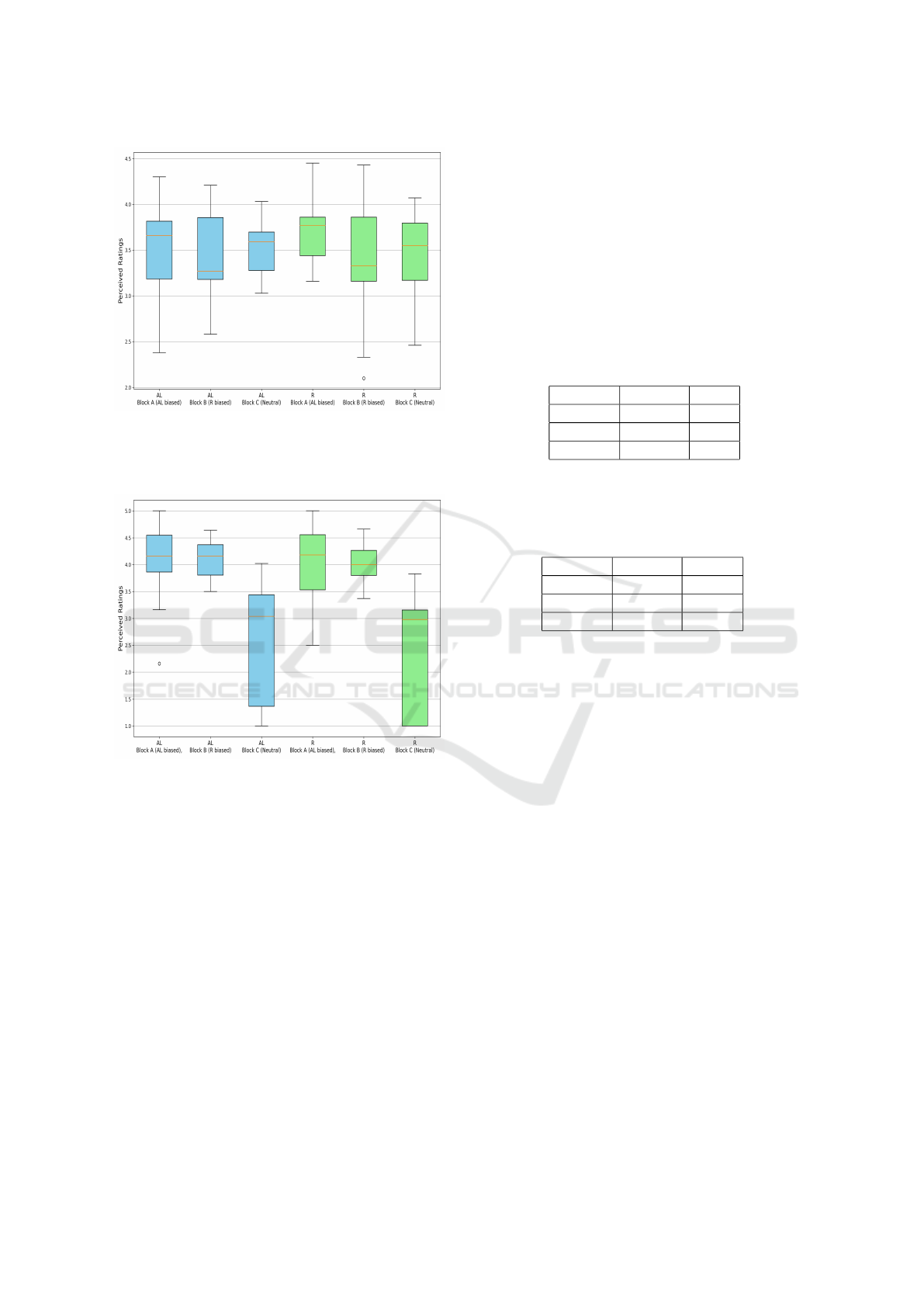

Handmade Dialogues: For handmade dialogues, as

depicted in Figure 4, for the perception of Active Lis-

tening (blue) we can see that participants identified

slightly more active listening in the active listening

biased data Block A than was the case for the neutral

data Block C. Similarly for the perception of reassur-

ance (green), participants perceived slightly greater

levels of reassurance on average in reassurance biased

data than was the case for the neutral data Block C. In

both cases however the effect is not strong, and statis-

tical tests shown in Table 3 demonstrate that the effect

was not significant across blocks. It is also notable

that reassurance and active listening perceptions cross

bias blocks are very similar. In other words partici-

pants see reassurance in Active Listening biased data

and see Active Listening in Reassurance biased data.

Though the reported values were lower, it is notable

here that the users perceived active listening and re-

assurance even in the neutral Block C data. This may

be due to various factors such as tone, context, and

non-verbal cues. In fact, language does not necessar-

ily eliminate all the cues that can influence the per-

ception of active listening or assurance, as no effort

was made to actively engineer this out of the baseline

dialogues.

Quantifying the Role of Active Listening and Reassurance in Virtual Health Coach Interactions

453

Figure 4: User Perception of Active Listening (Blue) and

Reassurance (Green) across Handmade Content. Block A

(Active Listening), Block B (Reassurance) and Block C

(Neutral).

Figure 5: User’s Perception of Active Listening (Blue)

and Reassurance (Green) across LLM-Generated Content.

Block A (Active Listening), Block B (Reassurance) and

Block C (Neutral).

LLM Generated Data: Turning to the LLM data,

Figure 5 presents a similar analysis for the LLM data.

Generally the results follow the same overall pattern

as those for the handcrafted content, but with a much

clearer distinction between the perception results for

neutral dialogues versus the dialogues that were bi-

ased towards reassurance and active listening. As was

the case for handcrafted dialogues, again we see that

participants do in fact perceive high values of active

listening in dialogues which were biased for reassur-

ance, and vice versa. While comparing to those re-

sults for the handcrafted dialogues, it is clear that the

measures of reassurance and active listening are in-

stinctively clearer for LLM generated data than hand-

crafted dialogue. Statistical analysis by means of

Anova with post-hoc Tukey’s HSD shows significant

differences in both active listening and reassurance

perceptions across the experimental blocks. These

findings underscore the potential of the engineered

stimuli successfully influencing perceptions of active

listening and reassurance. Tables 5 and 6 show the

detailed results of the Anova with post-hoc Tukey’s

HSD Test across the 3 blocks.

Table 5: Anova with post-hoc Tukey’s HSD Test Results

for the perception of Active Listening across the different

blocks of LLM-Generated Data. Block A (Active Listen-

ing), Block B (Reassurance) and Block C (Neutral).

Group 1 Group 2 p-adj

Block A Block B 1.0

Block A Block C 0.0

Block B Block C 0.0

Table 6: Anova with post-hoc Tukey’s HSD Test Results

for the Perception of Reassurance Across the Different

Blocks of LLM-Generated Data. Block A (Active Listen-

ing), Block B (Reassurance) and Block C (Neutral).

Group 1 Group 2 p-adj

Block A Block B 0.9986

Block A Block C 0.0

Block B Block C 0.0

4.3 Personality Variance in Perception

While it is interesting to understand whether the over-

all population can perceive of active listening and re-

assurance in designed content, it is important to rec-

ognize the potential for individual differences. There-

fore, we also collected personality measures to ana-

lyze whether personality traits correlate with the per-

ceptions of active listening and reassurance for each

participant in the LLM-generated content.

We present this analysis for the LLM sourced data.

As shown in the previous section the perceptions of

active listening and reassurance were most strongly

pronounced in this data, which in turn makes the in-

teractions with personality traits most valid for inves-

tigation. Our hypothesis is the existence of a linear

relationship between elements of personality measure

and perception measures of active listening and reas-

surance, To measure the strength and direction of the

this relationship we used Pearson’s correlation coeffi-

cient (r). Since different participants reviewed stimuli

across three stylistic blocks, we present the results for

these stylistic blocks individually. Table 7 summa-

rizes these results.

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

454

Table 7: Pearson Correlation Coefficient (r) between personality traits and blocks with active listening, reassurance biased

and neutral data. AL= Active Listening, R= Reassurance, *p values < 0.01 and **p < 0.05.

Personality Trait

Active Listening biased data Reassurance biased data Neutral data

AL R AL R AL R

Openness 0.2590 0.2599 0.0128 0.0128 -0.0783 -0.1623

Conscientiousness -0.0023 -0.0069 0.0993 0.0457 0.2610 0.1638

Extroversion 0.3977

**

0.2676 -0.4674

*

-0.5339

*

0.0017 -0.1054

Agreeableness 0.2218 0.2596 0.0923 -0.1859 -0.0622 -0.0432

Emotional Stability 0.3937

**

0.3765

**

-0.0622 -0.0051 0.0138 -0.0437

5 DISCUSSION

Our analysis suggests that when dialogues are con-

sciously crafted with language styles that indicate ac-

tive listening and reassurance, users are more likely

to perceive these dialogues as demonstrating those

traits compared to dialogues lacking such intentional

linguistic and social behavior cues. Our study re-

veals that users consistently perceived higher levels

of Active Listening and Reassurance in content gen-

erated by LLMs compared to hand-crafted data. This

discrepancy can likely be attributed to the advanced

content generation capabilities of LLMs when guided

by specific directives and instructions. Additionally,

it is crucial to acknowledge the possibility that user

comprehension may have been hindered during the

creation of hand-crafted data due to potential limita-

tions or inadequacies in conveying the intended lan-

guage styles. In either case the findings suggest that

we can comfortably use LLM generated content that

is tuned to the factors associated with good bedside

manner, and in fact these systems may be better at

consistently demonstrating these qualities than a hu-

man consciously aiming to replicate these styles.

While our study did not demonstrate any strong rela-

tionship between personality traits and the perception

of properties associated with good bedside manner,

that is a positive thing from the perspective of effec-

tive design of health supporting systems in the long

run. The results suggest that we do not need to over-

think the design of these stylistic factors and that with

respect to these elements of support, a one size fits

all approach to displaying support may be sufficient

rather than a dynamic style which needs to be cus-

tomized to individual personality traits.

6 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

DIRECTIONS

Whilst past studies on Virtual Health Coaching Assis-

tants have emphasised the positive impact of certain

tasks mainly providing information related to regime

prescription and physical assessment, little has been

known about focusing on the social aspects of inter-

action management, To address this gap, our study

focused on inclusion and measuring of social be-

haviours, namely active listening and reassurance, in

the context of system-initiated virtual health coaching

assistants. By building and analysing a dataset com-

prised of 135 dialogues, including original, handmade

and LLM-generated excerpts curated with language

styles related to these qualities, we observed that users

with diverse personality traits perceived varying lev-

els of active listening and reassurance. Our findings

underscore the importance of integrating these social

behaviors into virtual health coaching assistants. This

study laid the foundation work for filling the gap in

understanding and leveraging such behaviors, paving

the way for the development of virtual health coach-

ing prototypes that prioritize active listening and re-

assurance.

Building upon these findings, our future research en-

deavors focuses on developing a virtual health coach-

ing prototype that incorporates varying degrees of ac-

tive listening and reassurance, and validating that dis-

playing these qualities in a controlled way in fact is

beneficial to the participants. Through rigorous exper-

iments, our aim is to determine whether these qual-

ities indeed enhance engagement and effectiveness

compared to systems lacking these qualities. Ulti-

mately, our work aims to contribute to the advance-

ment of virtual health coaching, offering more per-

sonalized and adaptive interventions.

Quantifying the Role of Active Listening and Reassurance in Virtual Health Coach Interactions

455

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was conducted with the financial sup-

port of Science Foundation Ireland / Research Ire-

land under Grant Agreement No. 13/RC/2106 P2 at

ADAPT, the SFI Research Centre for AI-Driven Digi-

tal Content Technology. For the purpose of Open Ac-

cess, the authors have applied a CC BY public copy-

right licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript ver-

sion arising from this submission..

REFERENCES

Ahmad, R., Siemon, D., Gnewuch, U., and Robra-Bissantz,

S. (2022). Designing personality-adaptive conversa-

tional agents for mental health care. Information Sys-

tems Frontiers, 24.

Beinema, T., op den Akker, H., Hermens, H. J., and van

Velsen, L. (2023). What to discuss?—a blueprint

topic model for health coaching dialogues with con-

versational agents. International Journal of Hu-

man–Computer Interaction, 39(1):164–182.

Beinema, T., op den Akker, H., van Velsen, L., and

Hermens, H. (2021). Tailoring coaching strategies

to users’ motivation in a multi-agent health coach-

ing application. Computers in Human Behavior,

121:106787.

Berman, A. and Chutka, D. (2016). Assessing effective

physician-patient communication skills: ”are you lis-

tening to me, doc?”. Korean journal of medical edu-

cation, 28.

Cohen Rodrigues, T. R., de Buisonj

´

e, D. R., Reijnders,

T., Santhanam, P., Kowatsch, T., Breeman, L. D.,

Janssen, V. R., Kraaijenhagen, R. A., Atsma, D. E.,

and Evers, A. W. (2024). Human cues in ehealth to

promote lifestyle change: An experimental field study

to examine adherence to self-help interventions. In-

ternet Interventions, 35:100726.

Ding, Z., Kang, J., HO, T. O. T., Wong, K. H., Fung, H. H.,

Meng, H., and Ma, X. (2022). Talktive: A conversa-

tional agent using backchannels to engage older adults

in neurocognitive disorders screening.

Elliott, M. (2018). Good bedside manner. Online.

Eyal, P., David, R., Andrew, G., Zak, E., and Damer, E.

(2021). Data quality of platforms and panels for online

behavioral research. Behavior Research Methods, 54.

Fassaert, T., Dulmen, A., Schellevis, F., and Bensing,

J. (2007). Active listening in medical consulta-

tions: Development of the active listening observation

scale (alos-global). Patient education and counseling,

68:258–64.

Fernau, D., Hillmann, S., Feldhus, N., Polzehl, T., and

M

¨

oller, S. (2022). Towards personality-aware chat-

bots. In Lemon, O., Hakkani-T

¨

ur, D., Li, J. J.,

Ashrafzadeh, A., Garc

´

ıa, D. H., Alikhani, M.,

Vandyke, D., and Dusek, O., editors, Proceedings of

the 23rd Annual Meeting of the Special Interest Group

on Discourse and Dialogue, SIGDIAL 2022, Edin-

burgh, UK, 07-09 September 2022, pages 135–145.

Association for Computational Linguistics.

Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., and Swann Jr, W. B. (2003).

A very brief measure of the big-five personality do-

mains. Journal of Research in personality, 37(6):504–

528.

Hallal, P. C., Andersen, L. B., Gonc¸alves, L. G., Wells, J. C.,

Reichert, F. F., Anjos, L. A. d., Ferreira, R. C., and

Victora, C. G. (2016). Physical activity and inactivity

profiles in brazilian adults: results from the national

health survey (pns 2013). Revista de sa

´

ude p

´

ublica,

50:1S.

Heinz, B. M. (1998). Backchannel responses as conversa-

tional strategies in bilingual speakers’ conversations.

The University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Hicks, K. M., Cocks, K., Martin, B. C., Elton, P. J., Macnab,

A., Colecliffe, W., and Furze, G. (2014). An interven-

tion to reassure patients about test results in rapid ac-

cess chest pain clinic: a pilot randomised controlled

trial. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders, 14.

Jagosh, J., Donald Boudreau, J., Steinert, Y., MacDon-

ald, M. E., and Ingram, L. (2011). The impor-

tance of physician listening from the patients’ per-

spective: Enhancing diagnosis, healing, and the doc-

tor–patient relationship. Patient Education and Coun-

seling, 85(3):369–374.

Karlsson, V., Forsberg, A., and Bergbom, I. (2012). Com-

munication when patients are conscious during respi-

rator treatment—a hermeneutic observation study. In-

tensive and Critical Care Nursing, 28(4):197–207.

King, G. (2021). Central yet overlooked: engaged and

person-centred listening in rehabilitation and health-

care conversations. Disability and rehabilitation,

44:1–13.

Lala, D., Milhorat, P., Inoue, K., Ishida, M., Takanashi, K.,

and Kawahara, T. (2017). Attentive listening system

with backchanneling, response generation and flexible

turn-taking. In Proceedings of the 18th Annual SIG-

dial Meeting on Discourse and Dialogue, pages 127–

136, Saarbr

¨

ucken, Germany. Association for Compu-

tational Linguistics.

Liang, K.-H., Lange, P., Oh, Y. J., Zhang, J., Fukuoka, Y.,

and Yu, Z. (2021a). Evaluation of in-person counsel-

ing strategies to develop physical activity chatbot for

women. arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.10410.

Liang, K.-H., Lange, P., Oh, Y. J., Zhang, J., Fukuoka, Y.,

and Yu, Z. (2021b). Evaluation of in-person counsel-

ing strategies to develop physical activity chatbot for

women. In Li, H., Levow, G.-A., Yu, Z., Gupta, C.,

Sisman, B., Cai, S., Vandyke, D., Dethlefs, N., Wu, Y.,

and Li, J. J., editors, Proceedings of the 22nd Annual

Meeting of the Special Interest Group on Discourse

and Dialogue, pages 32–44, Singapore and Online.

Association for Computational Linguistics.

Lynch, J., Hughes, G., Papoutsi, C., Wherton, J., and

A’Court, C. (2022). “it’s no good but at least i’ve

always got it round my neck”: A postphenomeno-

logical analysis of reassurance in assistive technology

use by older people. Social Science and Medicine,

292:114553.

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

456

Moore, R., Al-Tamimi, A.-K., and Freeman, E. (2023). A

conversational agent (phyllis) to support adolescent

health and overcome barriers to physical activity: a

co-design and evaluation study (preprint). JMIR For-

mative Research, 8.

O’Keeffe, M., Cullinane, P., Hurley, J., Leahy, I., Bunzli,

S., O’Sullivan, P. B., and O’Sullivan, K. (2016). What

Influences Patient-Therapist Interactions in Muscu-

loskeletal Physical Therapy? Qualitative Systematic

Review and Meta-Synthesis. Physical Therapy, 96(5).

´

Olafsson, S., O’Leary, T. K., and Bickmore, T. W. (2019).

Coerced change-talk with conversational agents pro-

motes confidence in behavior change. Proceedings of

the 13th EAI International Conference on Pervasive

Computing Technologies for Healthcare.

Rolfe, A. and Burton, C. (2013). Reassurance after diag-

nostic testing with a low pretest probability of serious

disease. JAMA internal medicine, 173:1–9.

Ruede, R., M

¨

uller, M., St

¨

uker, S., and Waibel, A. (2017).

Yeah, right, uh-huh: A deep learning backchannel pre-

dictor.

Sahijwani, H. (2022). Adaptive dialogue management for

conversational information elicitation. In Proceedings

of the 45th International ACM SIGIR Conference on

Research and Development in Information Retrieval,

pages 3495–3495.

Shan, Y., Ji, M., Xie, W., Qian, X., Li, R., Zhang, X.,

and Hao, T. (2022). Language use in conversa-

tional agent–based health communication: System-

atic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research,

24:e37403.

Snyder, U. (2008). The doctor-patient relationship ii: Not

listening. Medscape journal of medicine, 10:294.

Traeger, A., O’Hagan, E., Cashin, A., and Mcauley, J.

(2017). Reassurance for patients with non-specific

conditions – a user’s guide. Brazilian Journal of Phys-

ical Therapy, 21.

Wu, Z., Balloccu, S., Kumar, V., Helaoui, R., Refor-

giato Recupero, D., and Riboni, D. (2023). Cre-

ation, analysis and evaluation of annomi, a dataset of

expert-annotated counselling dialogues. Future Inter-

net, 15(3).

Wutz, M., Hermes, M., Winter (n

´

ee Hinz), V., and

Koeberlein-Neu, J. (2023). Factors influencing the ac-

ceptability, acceptance and adoption of conversational

agents in healthcare: An integrative review (preprint).

Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25.

APPENDIX

A: Survey Questions

Research survey included a total of six questions,

specifically focused on examining the perception of

active listening and reassurance. The first three ques-

tions assessed active listening, while the remaining

three questions referred to reassurance.

1. How well did therapist demonstrate active listen-

ing by paying attention and showing interest in

clients concerns?

2. Did the therapist ask questions or provide feed-

back that demonstrated understanding and active

listening?

3. Did the therapist give cues or responses that

showed they were actively listen and paying at-

tention?

4. Did the therapist acknowledge and validate the

client’s concerns or emotions that demonstrated

reassurance?

5. How well did the therapist provide reassurance,

comfort, support, or encouragement to the client?

6. How effective was the therapist in fostering a

sense of reassurance and encouragement for the

client’s overall progress?

B: Designed Prompts

To generate synthetic data, we used ChatGPT 3.5

with different prompts to generate dialogue excerpts

in specific styles, which depicts qualities related to

active listening and reassure.

• Write a dialogue where the therapist actively lis-

tens to the client’s concerns about their progress

in therapy and reassures them with empathy and

understanding

• Craft a scenario where the client expresses anx-

iety about their ability to recover fully, and the

therapist listens attentively while providing reas-

surance and support

• Imagine a dialogue between a therapist and a

client where the client expresses frustration with

their current treatment plan. How does the ther-

apist respond with active listening and reassur-

ance?

• Create a conversation where the client shares their

fears about returning to activities that caused their

injury, and the therapist responds by actively lis-

tening and offering reassurance and guidance

• Write a dialogue where the client discusses feel-

ings of self-doubt and uncertainty about their

progress, and the therapist responds by validating

their concerns and providing reassurance.

Quantifying the Role of Active Listening and Reassurance in Virtual Health Coach Interactions

457