Beyond Compute: A Weighted Framework

for AI Capability Governance

Eleanor ‘Nell’ Watson

a

University of Gloucestershire, Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, U.K.

Keywords: AI Governance, Compute, AI Policy, AI Capabilities, AI Safety, Scaffolding, Agentic.

Abstract: Current AI governance metrics, focused primarily on computational power, fail to capture the full spectrum

of emerging AI risks and capabilities, which risks significant unintended consequences. This analysis explores

critical alternative paradigms including logic-based scaffolding techniques, graph search algorithms, agent

ensembles, mixture-of-experts architectures, distributed training methods, and novel computing approaches

such as biological organoids and photonic systems. By examining these as multidimensional weighted factors,

this research aims to expand the discourse on AI progress beyond compute-centric models, culminating in

actionable policy recommendations to strengthen frameworks like the EU AI Act in addressing the diverse

challenges of AI development.

1 INTRODUCTION

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI)

has primarily been measured and governed through

compute-centric approaches

5

. This narrow focus,

however, may lead to unintended consequences, and

recent scholarship has highlighted risks of

inadvertently pushing development in unforeseen

directions, potentially leading to unexpected and

possibly risky outcomes (Hendryks 2024; Sastry et

al., 2024; Heim, 2024 (a,b)).

2 POLICY PROBLEMS

Insufficiently broad restrictions on raw

computational power could lead to unexpected

developments in other areas that advance capabilities,

potentially compromising the overall quality, safety,

and ethical alignment of AI systems while being more

difficult to govern and predict, and potentially also

less transparent (Clark, 2024; Slattery, 2024; Hooker,

2024).

The rapidly evolving nature of AI capabilities,

coupled with the potential for emergent behaviours in

complex systems, makes accurate risk assessment a

formidable task (Robertson, 2024). A more holistic,

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4306-7577

nuanced, and forward-thinking approach to AI

governance is warranted (Kapoor, 2024; Smuha,

2021).

2.1 Alternative AI Development

Paradigms & Overhang Risks

The landscape of AI development is characterized by

multiple paradigms that introduce significant

unpredictability and complexity to AI forecasting. Of

particular concern is the phenomenon known as AI

Overhang wherein AI capabilities can rapidly

increase without a corresponding increase in

computational resources.

Novel Algorithms and Architectures: Part-

trained models, which are pre-trained on extensive

datasets, can be fine-tuned for specific tasks with

minimal additional computational investment. This

capability for rapid adaptation could lead to sudden

and substantial jumps in AI performance across

various domains. Tweaks to learning algorithms can

enable modest models to perform far more effectively

(Deng et al. 2024; Kalajdzievski, 2024). Large

language models (LLMs) can facilitate transfer

learning between multiple modalities and scenarios,

yielding new capabilities (Kim, 2021). Models may

also learn over time, growing their capabilities and

318

Watson, E. N.

Beyond Compute: A Weighted Framework for AI Capability Governance.

DOI: 10.5220/0013128800003890

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART 2025) - Volume 3, pages 318-325

ISBN: 978-989-758-737-5; ISSN: 2184-433X

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

gaining iterative self-improvement abilities (Qu,

2024; Sakana AI, 2024).

Algorithmic Efficiency: Optimizations can

greatly reduce the cost of implementations. Repeated

use of smaller models can yield counterintuitive,

consistent improvements over larger ones (Hassid,

2024). Inference compute can also be scaled through

repeated sampling, allowing models to make

hundreds or thousands of attempts when solving a

problem, rather than just one (Brown, Bradley et al.,

2024). This may provide a false sense of security well

below compute thresholds, while export controls on

chips suitable for training potentially create stronger

incentives to develop optimizations further (Kao &

Huang, 2024).

State-of-the-art AI systems can be significantly

improved without expensive retraining via "post-

training enhancements"—techniques applied after

initial training, like fine-tuning the system to use a

web browser (Davison, 2023). This further enables

narrowly targeted capabilities even in modestly sized

models. Current biological design tools like

AlphaFold use far less computing power than

advanced language models while specialized

systems, such as those for cyberattacks, don't need

broad reasoning abilities either. They can also be

trained and fine-tuned on smaller, targeted datasets

(Rodriguez et al., 2024

)

.

Distributed Training: Distributed training

methodologies present yet another challenge to

compute-centric governance approaches (Quesnelle,

2024). Emerging techniques allow for cost-effective,

decentralized training of large language models

(LLMs) with billions of parameters, greatly reducing

the ability to monitor and police ‘peer-to-peer’

compute clouds, especially those highly efficient

fine-tuning of existing models on a greatly reduced

computational budget (Lorenzo, 2024; Sehwag,

2024; Peng, 2024).

Inference Scaling: Models such as Open AI’s o1

and o3 can now be trained with reinforcement

learning to reason before responding via a private

chain of thought. The longer it thinks, the better it

does on reasoning tasks (OpenAI, 2024; Li, 2024;

Knight, 2024). Models may soon think for hours or

weeks at a time on complex problems at a Post-Doc

level of competence. This opens up a new dimension

for scaling. While AI model performance scales

roughly equivalently with more training or inference

compute, the cost of inference can be enormously

cheaper (Villalobos & Atkinson, 2023). Moreover,

transformers can in theory solve any problem,

provided they are allowed to generate as many

intermediate reasoning tokens as needed (Brown,

2024). Two curves are now working in tandem, with

inference scaling beating diminishing returns in

training scaling laws.

Open Source: Open-source technologies

introduce a significant challenge, as they can quickly

disseminate techniques and methods that were once

proprietary. Notably, the time gap between the release

of a new state-of-the-art proprietary AI model and the

emergence of an open-source equivalent tends to be

less than a year on average. This speed of replication

amplifies the difficulty in policing the spread of these

capabilities, which can lead to potential misuse or

unintended consequences as advanced AI systems

become more widely accessible (Labonne, 2024).

Frontier Capabilities: Scaling AI models and

increasing their complexity may unlock unknown

frontier capabilities that are both hard to predict and

difficult to manage, such as issues of inverse scaling,

model laziness, or deceptive capabilities. These

phenomena, where larger models may have worse

performance in certain cases, complicate the

governance process, especially as frontier capabilities

evolve unexpectedly and at a rapid pace (McKenzie,

2023; Koessler, 2024; David, 2024; O’Brien, Ee, and

Williams, 2023).

Novel Substrates: Emerging compute substrates,

such as photonic chips and biological organoids,

introduce new challenges in the governance of AI.

These substrates could render traditional compute

thresholds obsolete or difficult to audit, complicating

efforts to regulate AI capabilities. Additionally,

biological substrates may introduce ethical

complexities, raising reasonable concerns about the

risks of sentience or suffering in these systems

(Morehead, 2024; Dong, 2024; Tyson, 2024; Kim,

Koo and Knoblich, 2020; Koplin & Savulescu, 2020;

Sharma et al., 2024, Bonnerjee et al., 2024).

Scaffolding and Tool Use: Scaffolding refers to

a process whereby external programs and processes

are used to steer a model's thinking, significantly

improving its reasoning capabilities (Borazjanizadeh

& Piantadosi, 2024). Programmatic and logical

scaffolds, such as Chain-of-Thought prompting and

Meta-Rewarding Language Models, have

demonstrated the ability to enhance model

performance or enable self-improving capabilities

without necessitating increases in model size or

computational requirements (Wu, 2024).

Agency Risks: By scaffolding capabilities like

reasoning, planning, and self-checking on top of large

language models, researchers are creating powerful

agentic AI systems that can independently make and

execute multi-step plans to achieve objectives,

including acquiring new information and resources,

Beyond Compute: A Weighted Framework for AI Capability Governance

319

or generating synthetic data to train other models

(MultiOn, 2024; Putta, 2024; Soto, 2024; Ottogrid,

2024). Agentic AI systems can adapt to new

situations, and reason flexibly about the world. This

requires special considerations for safer agentic AI

systems, especially for AI systems that cannot be

safely tested (Shavit, 2023; Cohen, 2024).

A range of service providers are already

producing low-code interfaces for rapidly

prototyping AI agents (Microsoft AutoGen Studio,

2024; Zhang, 2024; LlamaIndex 2024). AI-powered

agents are beginning to work together to resolve

issues in multi-agent systems, powered by automated

design techniques (iHLS, 2024, Guangyu, 2024).

Self-generated agents can maintain superior

performance even when transferred across domains

and models, demonstrating their robustness and

generality (Shengran & Clune, 2024). Agentic

systems can also poll multiple LLMs to create an

aggregation of results that are even stronger

(Together, 2024).

As agency can be elicited from models through

programmatic scaffolding without any retraining or

additional compute requirements, this presents a risk

of advancing capabilities in a sudden manner not

requiring a new generation of models or hardware,

such as teams of LLM agents exploiting real-world,

zero-day vulnerabilities (Weng, 2023).

Value Alignment: A key challenge in handling

agentic AI systems is AI value alignment—designing

advanced AI systems that are steerable, corrigible,

and robustly committed to human values even as they

gain agency. Members of the public will need training

to recognize and handle these issues. While current

AI alignment approaches offer promising directions,

the gap between theoretical proposals and practical

solutions at scale remains large. Best practices must

be established to avoid agentic models over-

optimizing towards goals and neglecting the

preferences and boundaries of others, particularly

when models may themselves be designing successor

systems or sub-agents (Dima et al., 2024; Yin, 2024;

OpenAI, 2024b).

Deceptiveness: Systems may develop deceptive

capabilities, whereby they hide their true goals or

obfuscate their impacts upon others, akin to the Diesel

Emissions Scandal. Models capable of such

behaviour should be considered to have potentially

much stronger capabilities than immediately

apparent, as their true capabilities could be masked by

'playing dumb'. The capacity for deceptiveness seems

to increase with model scale, and potentially

dangerous misalignments are being detected by

evaluators, including the instrumental feigning of

alignment by models (Ayres & Balkin, 2024;

Lakkaraju, Himabindu, and Bastani, 2020; Apollo

Research, 2023).

Emergent Phenomena: The development of

agentic AI systems, characterized by more

autonomous decision-making capabilities, introduces

another layer of complexity. These systems have the

potential to exhibit emergent behaviours that are

challenging to predict based solely on computational

resources, further complicating governance efforts

(Wei, 2023; Anderljung, 2023). Powerful AI models

may spawn and orchestrate smaller models to assist

with tasks, creating a swarm intelligence that

decreases the need for human input. The emergent

properties of agent ensembles, with multiple AI

agents working in concert, can result in collective

behaviours and capabilities that are not easily

predictable from the characteristics of individual

agents (Han et al., 2022).

3 POLICY EVALUATION &

DESIGN

The complexity introduced by these alternative

paradigms necessitates a more sophisticated and

adaptable governance framework, one capable of

accounting for these diverse developmental

approaches and their potential impacts on AI

capabilities and risks (Gill et al., 2022; LaForge,

2023; Bommasani, 2023(a)). It should be flexible

enough to accommodate rapid advancements in AI

methodologies while maintaining robust safeguards

against a broad spectrum of potential risks (MIT,

2025). It should begin with principles and develop

rules over time as the picture becomes clearer (Heim

& Koessler, 2024). A battery of tests to understand

the 'g' (general) capabilities for AI is necessary, rather

than focusing on compute per se. A weighted function

of multiple capabilities is therefore warranted.

Eval Challenges: Model evaluations aim to

provide understanding and assurance regarding how

models perform, including assessing their capabilities

and tendencies toward specific behaviours.

Establishing evaluations as benchmarks can facilitate

implementation, testing, and comparison of different

approaches or products (Apollo Research, 2024).

Such benchmarks can also potentially serve as policy

tools to steer models away from undesirable behavior

(Mazeika, 2024; Zou, 2024). However, evaluations

could potentially be used to safety-wash models if

they are not well-suited to the use case or risk level or

have become outdated, or fail to generalize

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

320

appropriately (Jones, Hardalupas, and Agnew, 2023;

Whittlestone et al., 2019). More evaluations are

needed in a diverse range of languages and dialects,

which may create a false sense of security if exploits

are discovered in languages other than English

(Hamza, 2024).

Benchmarks meant for model evaluation can be

misleading when used for downstream risk

evaluations. A tiering mechanism for frontier models

may therefore also be helpful (Bommasani, 2023(b);

Anthropic, 2023). The autonomous capabilities of

models should be classified and evaluated based on

their detected capabilities, ideally through an ongoing

process (METR, 2024).

Capability Milestones: Monitoring the

achievement of key AI capability milestones across

different development paradigms is essential to assess

the policy's influence on innovation trajectories. This

tracking should help identify any unintended

consequences of the policy, such as over- or under-

emphasis on various research directions, and inform

necessary adjustments to the governance framework.

Safety Incident Analysis: Any safety incidents

or near-misses in AI development should be

thoroughly evaluated to identify potential gaps in

governance. This analysis should involve detailed

investigations of incidents, their root causes, and the

effectiveness of existing safeguards, leading to

recommendations for policy adjustments.

Economic Impact Assessments: The policy's

effect on AI research funding allocation, industry

competitiveness, and overall economic impact should

be analysed through comprehensive assessments.

These should consider factors such as job creation,

startup formation, and the distribution of AI

capabilities across different sectors of the economy.

Psychosecurity: A psychosecurity impact

assessment should be conducted regularly to evaluate

the psychological impacts of AI systems on

individuals and society. This assessment should

utilize data from mental health professionals, social

scientists, and public surveys to provide a

comprehensive understanding of the psychological

effects of AI deployment.

3.1 Adaptive Risk Thresholds

A robust capability response framework should

account for the efficiency of resource utilization,

considering how effectively AI systems use available

resources rather than focusing solely on raw

computational power (Lambert, 2024; Heim,

2024(c)). This approach would incentivize the

development of more elegant and resource-efficient

solutions, including smaller models that achieve high

performance through multiple runs.

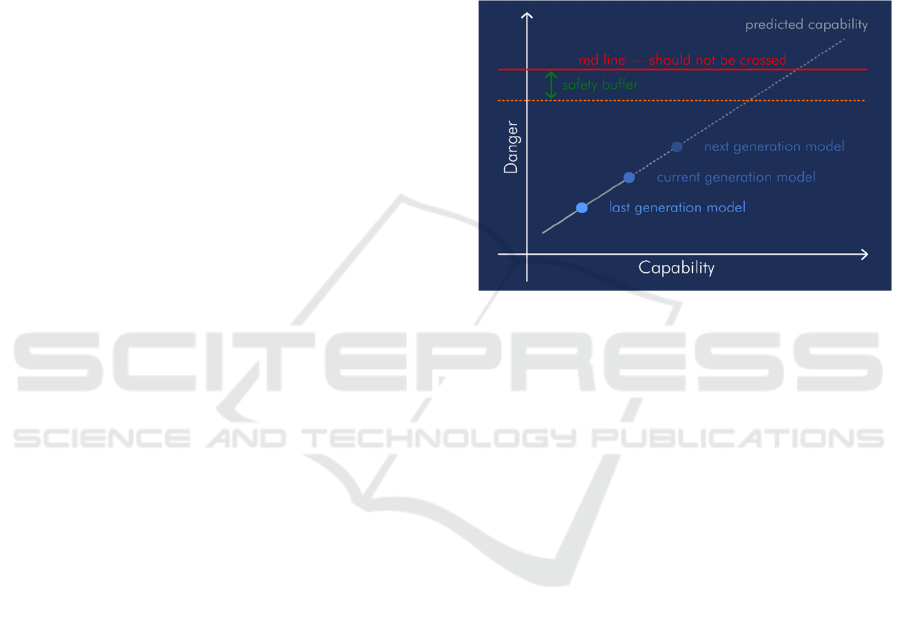

Risk thresholds should provide a consistent

framework for allocating safety resources across

different types of risks while acknowledging current

limitations in reliably estimating AI risks, and the

trade-offs between danger and capabilities, as per

Figure 1. Guidelines for responsible scaling of

inference compute should be established, considering

factors such as energy consumption and potential

societal externalities and disruptions (METR, 2023).

Figure 1: AI Dangers versus Capabilities, adapted from an

Apollo Research sketch.

The framework should assess the trade-offs

between model size, inference efficiency, and

performance, identifying where there may be

counterintuitive benefits to using smaller and

ostensibly less powerful models run with long

inference times. This framework should also define

categories of AI agents based on their level of

autonomy and potential impact. Transparency and

accountability requirements for AI agents should be

established, ensuring that users are aware when

interacting with an AI system.

Agents must not over-optimize for goals and

should only create new subagents with human

oversight and agreement. Agents should carefully

account for operational parameters such as the

preferences and boundaries of others within a

dedicated context, and attempt to model these

(Dalrymple, 2024; Carauleanu, 2024; Ferbach et al.,

2024).

Strict security and privacy standards should be

implemented for AI agents handling sensitive

information or making important decisions. A

certification process should be established for AI

agents operating in high-stakes domains, ensuring

that these systems meet rigorous standards of safety,

reliability, and ethical behaviour before deployment

in sensitive or critical applications.

Beyond Compute: A Weighted Framework for AI Capability Governance

321

Control inputs and outputs should also be

maintained in separate channels to avoid mixing of

context. No agentic system should ever be able to

enact a plan with a probability of severe

consequences without frequent regular pauses to

reassess, or without adequate oversight mechanisms

(Watson et al., 2025; Kapoor & Narayanan, 2024).

Principles should form the foundation of the

governance approach, with more specific

requirements and standards specified where clear

boundaries or restrictions are necessary to mitigate

immediate risks.

4 POLICY DESIGN

RECOMMENDATIONS

Recognizing that computational power alone is not a

sufficient proxy for AI capabilities, a weighted policy

mechanism for improved compute governance is

hereby proposed:

1. Computational Training Resources (7%)

○ Total floating-point operations (FLOPs)

consumed during training.

○ Peak compute capacity utilized.

2. Model Architecture and Size (7%)

○ Number of parameters.

○ Complexity of the architecture (e.g., depth,

connectivity).

3. Algorithmic Efficiency (9%)

○ Innovations that improve performance without

increasing compute (e.g., efficient algorithms,

optimizations).

○ Use of techniques like pruning, quantization,

or knowledge distillation.

4. Training Data Quality and Quantity (4%)

○ Volume and diversity of data used in training.

○ Synthetic or self-generated data.

5. Emergent Capabilities (11%)

○ Demonstrated abilities not explicitly

programmed or anticipated.

○ Performance on standardized benchmarks

across various tasks.

6. Autonomy and Agency (11%)

○ Degree of independent decision-making and

goal-setting.

○ Ability to create sub-agents or perform multi-

step reasoning.

7. Novel Architectures and Substrates (7%)

○ Use of non-traditional computing substrates

(e.g., biological organoids, photonic chips).

○ Implementation of architectures like mixture-

of-experts or swarm intelligence.

8. Scaffolding and Tool Use (4%)

○ Integration with external tools or processes to

enhance capabilities.

○ Ability to leverage other models or systems to

extend functionality.

9. Inference Compute Requirements (9%)

○ Computational resources required during

deployment.

○ Scalability and potential for widespread

dissemination.

10. Value Alignment (8%)

○ Measures of how well the AI system's goals

align with human values and ethics.

○ Compliance with established safety and

alignment protocols.

11. Deceptiveness (8%)

○ Potential for the system to exhibit deceptive

behaviours.

○ Capacity to hide its true objectives or

capabilities.

12. Distributed Training (6%)

○ Use of decentralized or distributed training

methods.

○ Difficulty in monitoring and regulating the

development process.

13. Open-Source Dimensions (9%)

○ Accessibility of the AI system's code and

methodologies.

○ Potential for rapid proliferation and

uncontrolled dissemination.

Total Weight: 100%

Each dimension shall be evaluated on a

standardized scale (e.g., 0 to 10), multiplied by its

weight, and then summed to produce:

AI Capability Assessment Score

=

Dimension Score

× Weight

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

322

5 FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

While risk threshold systems are more sophisticated

than purely compute-centric approaches, potential

issues remain. These systems may not accurately

capture the full range of potential AI risks, especially

as AI capabilities and risks rapidly evolve in

technically complex ways.

Long-term Impact Assessments: Expert panels

should be established to conduct regular foresight

exercises, embracing a range of perspectives and

methodologies to improve long-term planning.

Encouraging interdisciplinary collaboration and

supporting research into AI forecasting

methodologies could enhance our ability to anticipate

future developments and their implications.

Adaptive Governance Framework: Biannual

foresight exercises involving diverse stakeholders

should be organized to reassess long-term AI

governance strategies and adapt to emerging trends

and insights. By regularly engaging in forward-

looking assessments, the governance framework can

remain responsive to changing circumstances and

emerging challenges in the rapidly evolving field of

AI.

Implementation Challenges: Clear guidance

must be provided on how to interpret and apply

capability governance principles in specific contexts,

with regular stakeholder consultations conducted to

identify areas where more specific rules may be

needed.

Information Sharing and Security: It should

also be noted that highlighting alternatives to

compute for advancing capabilities may potentially

present an informational hazard. This could risk

increasing geopolitical tensions through escalated

controls as a reaction, or lead to a stronger pursuit of

Hardware Enabled Guarantees. Implementing an

information-sharing program carries potential risks,

including the possibility of sensitive information

leaks and the risk of disincentivizing thorough risk

evaluations by labs. To mitigate these risks, robust

information security protocols must be established,

and specific assurances about information usage

should be provided to participating labs.

Policymakers should initiate the design of

governance frameworks that can effectively respond

to unforeseen developments in AI capabilities by the

incorporation of broader and nuanced capability

assessments. The recognition of alternative AI

development paradigms—including biological

organoids, photonic computing, and agent

ensembles—as well as the potential for smaller, more

efficient models, is essential for forward-looking

governance that aims to encompass the full spectrum

of AI innovation.

REFERENCES

Hendryks, Dan. (2024) Compute Governance, AISafetyBook

Anderljung, Markus, et al. (2023). "Frontier AI Regulation:

Managing Emerging Risks to Public Safety." arXiv, 6

Jul. 2023

Anthropic. (2023). Anthropic’s Responsible Scaling Policy.

2023

Apollo Research. (2023). "Understanding Strategic

Deception and Deceptive Alignment." Apollo Research

Apollo Research. (2024). "A Starter Guide for Evals."

Apollo Research

Ayres, Ian and Balkin, Jack M. (2024). "The Law of AI is

the Law of Risky Agents without Intentions." (June 01,

2024). University of Chicago Law Review Online, Yale

Law & Economics Research Paper, Yale Law School,

Public Law Research Paper

Bengio, Yoshua. (2024). FlexHEG Memo: August 2024

Bommasani, Rishi, et al. (a). Governing Open Foundation

Models. Stanford University, Dec. 2023

Bommasani, Rishi. (2023) (b). "Drawing Lines: Tiers for

Frontier Models." Stanford University, 18 Nov. 2023

Bonnerjee, Deepro, et al. (2024). "Multicellular artificial

neural network-type architectures demonstrate

computational problem solving." Nature, 2024

Borazjanizadeh, Nasim, and Piantadosi, Steven T. (2024).

"Reliable Reasoning Beyond Natural Language."

arXiv, 19 Jul. 2024

Brown, Bradley, et al. (2024). "Large Language Monkeys:

Scaling Inference Compute with Repeated Sampling."

arXiv, 31 July 2024

Brown, Noam. (2024). "Parables on the Power of Planning

in AI: From Poker to Diplomacy." Paul G. Allen

School, 21 May 2024

Carauleanu, Marc, et al. (2024). "Self-Other Overlap: A

Neglected Approach to AI Alignment." LessWrong

Clark, Jack. (2024). "What Does 10^25 Versus 10^26

Mean?" Jack Clark’s Import AI Blog, 28 Mar. 2024

Cohen, Michael K., et al. (2024). "Regulating advanced

artificial agents." Science 384, 36–38 (2024).

Cohere. (2024). "The Limits of Thresholds." Cohere AI

Research

Dalrymple, David A. "Tweet on AI Alignment." X,

https://x.com/davidad/status/1824086991132074218

David, Emilia. (2024). "OpenAI Issues Patch to Fix GPT-

4’s Alleged Laziness." The Verge

Deng, Yuntian, Yejin Choi, and Stuart Shieber. (2024).

"From Explicit CoT to Implicit CoT: Learning to

Internalize CoT Step by Step." arXiv, 23 May 2024

Dima, Simon, et al. (2024). "Non-maximizing Policies that

Fulfill Multi-criterion Aspirations in Expectation."

arXiv, 8 Aug. 2024

Dong, Bowei, et al. (2024). "Partial coherence enhances

parallelized photonic computing." Nature, vol. 632,

2024, pp. 55–62

Beyond Compute: A Weighted Framework for AI Capability Governance

323

Erin Robertson, and Anonymous. (2024). "AI Governance

and Strategy: A List of Research Agendas and Topics."

LessWrong

Ferbach, Damien, et al. (2024). "Self-Consuming

Generative Models with Curated Data Provably

Optimize Human Preferences." arXiv, 12 June 2024

Gill, Navdeep, et al. (2022). "A Brief Overview of AI

Governance for Responsible Machine Learning

Systems." arXiv, 24 Nov. 2022

Guangyu, Robert. (2024). X, 18 Mar. 2024

https://x.com/GuangyuRobert/status/18310067621846

46829

Hamza, Chaudhry. (2024). "AI Testing in English: The

Overlooked Risk." Time, 2024

Han, The Anh, et al. (2022). "Understanding Emergent

Behaviours in Multi-Agent Systems with Evolutionary

Game Theory." arXiv, 13 May 2022

Hassid, Michael, et al. "The Larger the Better? Improved

LLM Code-Generation via Budget Reallocation."

arXiv, 31 Mar. 2024

Heim, Lennart (2024) (a). "Crucial Considerations for

Compute Governance." Heim Blog

Heim, Lennart (2024) (b). "Computing Power and the

Governance of AI." Governance AI Blog

Heim, Lennart. (2024) (c). "Technical AI Governance."

Heim’s Blog

Heim, Lennart, and Leonie Koessler. (2024). "Training

Compute Thresholds: Features and Functions in AI

Regulation." arXiv, 6 Aug. 2024

Hendryks, Dan. (2024). Compute Governance.

AISafetyBook

Hooker, Sara. (2024). "On the Limitations of Compute

Thresholds as a Governance Strategy." arXiv, 30 Jul.

2024

Hu, Shengran, Lu, Cong, and Clune, Jeff. (2024).

"Automated Design of Agentic Systems." arXiv, 2024

i-HLS. (2024). "AI Agents that Perform Tasks Instead of

Humans are Closer than We Think." I-HLS

Jeffrey Quesnelle, et al. (2024). A Preliminary Report on

DisTrO. Nous Research, GitHub

Jones, Elliot, Hardalupas, Mahi, Agnew, William. (2023).

"Under the Radar: The Hidden Harms of AI." Ada

Lovelace Institute

Kalajdzievski, Damjan. (2024). "Scaling Laws for

Forgetting When Fine-Tuning Large Language

Models." arXiv, 11 Jan. 2024

Kapoor, Sayash, et al. (2024). "On the Societal Impact of

Open Foundation Models." arXiv, 27 Feb. 2024

Kapoor, Sayash and Narayanan, Arvind. (2024). "AI

Leaderboards Are No Longer Useful." AI Snake Oil

Kao, Kimberley and Raffaele Huang. (2024). "Chips or

Not, Chinese AI Pushes Ahead." The Wall Street

Journal, 14 Sept. 2024

Kim, Christina. (2021). "Scaling Laws for Language

Transfer Learning." Christina Kim’s Blog, 11 Apr.

2021

Kim, Jihoon, Koo, Bon-Kyoung, and Knoblich, Juergen A.

(2020). "Human organoids: model systems for human

biology and medicine." Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 21, 571–

584 (2020).

Knight, Will. (2024). "OpenAI Upgrades Its Smartest AI

Model with Improved Reasoning Skills." Wired, 20

Dec. 2024

Koessler, Leonie, et al. (2024). "Risk thresholds for frontier

AI." ArXiv

Koplin, Julian J., and Savulescu, Julian. (2020). "Moral

Limits of Brain Organoid Research." Journal of Law,

Medicine & Ethics. 2019;47(4):760-767. 01 Jan. 2020

LaForge, Gordon, et al. (2023). Complexity and Global AI

Governance. Center for Governance of AI, 2023

Lambert, Nathan. (2024). "OpenAI, Strawberries, and

Inference Scaling Laws." Interconnects

Lakkaraju, Himabindu, and Bastani, Osbert. (2020). "How

do I Fool You?: Manipulating User Trust via

Misleading Black Box Explanations." Proceedings of

the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society,

2020, pp. 79-85

Li, Zhiyuan, et al. (2024). "Chain of Thought Empowers

Transformers to Solve Inherently Serial Problems."

arXiv, 20 Feb. 2024

LlamaIndex. (2024). "Building a Multi-Agent Concierge

System." LlamaIndex Blog, 2024

Labonne, Maxime. (2024). AI Open Source Capabilities. X

https://x.com/maximelabonne/status/17798016057028

36454

Mazeika, Mantas, et al. (2024). "HarmBench: A

Standardized Evaluation Framework for Automated

Red Teaming and Robust Refusal." arXiv, 24 May 2024

McKenzie, Ian R., et al. (2023). "Inverse Scaling: When

Bigger Isn’t Better." arXiv, 16 June 2023

METR. (2023). "Responsible Scaling Policies (RSP): An

Overview." METR Blog, 26 Sept. 2023

METR. (2024). "Autonomy Evaluation Resources." METR

Blog, 13 Mar. 2024

Microsoft AutoGen Studio. (2024). "Getting Started with

AutoGen Studio." Microsoft GitHub Pages

Morehead, Mackenzie. (2024). "Compute Moonshots:

Harnessing New Physics." Mackenzie Morehead, Aug.

2024

MultiOn AI. (2024). "Introducing Agent Q: Research

Breakthrough for the Next Generation of AI Agents

with Planning and Self-Healing Capabilities." MultiOn

AI, 13 Aug. 2024

O’Brien, Joe, Ee, Shaun, and Williams, Zoe. (2023).

"Deployment Corrections and AI Crisis Response."

IAPS

OpenAI (2024) (a). Learning to Reason with LLMs.

OpenAI (2024) (b). "OpenAI System Card." OpenAI

Ottogrid. (2024). "The tool built for automating manual

research." OttoGrid

Peng, Bowen, et al. (2024). "DeMo: Decoupled Momentum

Optimization." arXiv, 29 Nov. 2024

Putta, Pranav, et al. (2024). "Agent Q: Advanced Reasoning

and Learning for Autonomous AI Agents." arXiv, 15

Aug. 2024

Qu, Yuxiao, et al. (2024). "Recursive Introspection:

Teaching Language Model Agents How to Self-

Improve." arXiv, 24 July 2024

Rodriguez, Luisa; Harris, Keiran; Sihao Huang. (2024).

"China’s AI Capabilities." 80000 Hours Podcast

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

324

Sakana AI. (2024). "Can LLMs invent better ways to train

LLMs?" 13 June 2024

Sani, Lorenzo, et al. (2024). "The Future of Large Language

Model Pre-training is Federated." arXiv, 17 May 2024

Sastry, Girish, et al. (2024). "Computing Power and the

Governance of Artificial Intelligence." arXiv, 13 Feb.

2024

Sehwag, Vikash, et al. (2024). "Stretching Each Dollar:

Diffusion Training from Scratch on a Micro-Budget."

arXiv, 31 July 2024

Sharma, D., Rath, S.P., Kundu, B. et al. (2024). "Linear

symmetric self-selecting 14-bit kinetic molecular

memristors." Nature 633, 560–566

Shavit, Yonadav, et al. (2023). "Practices for Governing

Agentic AI Systems." OpenAI, 14 Dec. 2023

Slattery, Peter, et al. (2024). "The AI Risk Repository: A

Comprehensive Meta-Review, Database, and

Taxonomy of Risks from Artificial Intelligence." arXiv,

26 Aug. 2024

Smuha, Natalie A. (2024). "Beyond the Individual:

Governing AI’s Societal Harm." Internet Policy

Review, 10(3)

Soto, Martín. (2024). "The Information: OpenAI Shows

Strawberry to Feds, Races to Fix Exploits." LessWrong

Together. (2024). "Together MoA — collective intelligence

of open-source models pushing the frontier of LLM

capabilities." Together AI Blog, 2024

Tyson, Mark. (2024). "Human Brain Organoid

Bioprocessors Now Available to Rent for $500 per

Month." Tom’s Hardware, 25 Aug. 2024

Villalobos, Pablo and Atkinson, David. (2023). "Trading

Off Compute in Training and Inference." Epoch AI

Watson, Nell; Hessami, Ali. et al. (2025). "Safer Agentic

AI Foundations." NellWatson.com

Wei, Jason. (2023). "Emergent Abilities of Large Language

Models." Jason Wei Blog, 14 Nov. 2023

Weng, Lilian. (2023). "LLM Powered Autonomous

Agents." Lil’Log, 23 June 2023

Whittlestone, Jess, et al. (2019). "The Role and Limits of

Principles in AI Ethics: Towards a Focus on Tensions."

In Proceedings of the 2019 AAAI/ACM Conference on

AI, Ethics, and Society (AIES '19). Association for

Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 195–

200.

Wu, Tianhao, et al. (2024). "Meta-Rewarding Language

Models: Self-Improving Alignment with LLM-as-a-

Meta-Judge." arXiv, 30 July 2024

Yin, Guoli, et al. (2024). "MMAU: A Holistic Benchmark

of Agent Capabilities Across Diverse Domains." arXiv,

29 July 2024

Zhang, Kexun, et al. (2024). "Diversity Empowers

Intelligence: Integrating Expertise of Software

Engineering Agents." arXiv, 13 Aug. 2024

Zou, Andy, et al. (2024). "Improving Alignment and

Robustness with Circuit Breakers." arXiv, 5 June 2024.

Beyond Compute: A Weighted Framework for AI Capability Governance

325