MILI: Biophotonics Technology for In-Situ, Fast, Accurate and

Cost-Effective Milk Analysis

Panayiota Demosthenous

1 a

, Maria Aspri

2 b

, Maria Moyseos

1 c

and Marios Sergides

1 d

1

Cy.R.I.C. Cyprus Research and Innovation Center Ltd, 28th October Avenue, 2414 Nicosia, Cyprus

2

Dept. of Agricultural Sciences, Biotechnology and Food Science, Cyprus University of Technology, 3036 Limassol, Cyprus

Keywords:

Fluorometry, Biophotonics, Biosensors, Optical Analysis, Automated System, Food Safety, Milk Analysis,

Embedded Electronics.

Abstract:

Contaminated milk poses serious health risks to consumers, highlighting the need for efficient detection meth-

ods. Currently, the dairy industry relies on precise but time-consuming laboratory methods that require special-

ized personnel. The work presented here aims to address this by developing a fast, cost-effective and reliable

system for detecting common contaminants in milk at the farm level. The MILI device is based on state-of-the-

art biophotonics, combining customised biosensors, optical analysis, electronics, and software modules. The

detection method relies on the use of fluorometry, where the signal originating from labelled antibodies bound

to specific analytes (antibiotics and toxins) is measured. Two different chromophore molecules suspended in

buffer and milk solutions were used to test the detection capabilities of the device with excitation/emission

wavelengths at 562 nm/584 nm and 650 nm/665 nm, respectively. We describe the different modules of the

device and present a detailed experimental work performed to validate the device operation and extract perfor-

mance parameters such as the limit of detection in terms of chromophore concentration, accuracy, sensitivity,

and specificity. The obtained results demonstrate reliable detection of low chromophore concentrations (<100

pM), with repeatability and robustness confirmed under different conditions, making the MILI system an ideal

candidate for rapid, cost-effective contamination detection device.

1 INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization (WHO) has recog-

nized food contamination as a global challenge in

several reports (World Health Organization, 2015;

Fukuda, 2015). Nearly 1 in 10 people worldwide be-

come ill by consuming contaminated food, leading to

420,000 deaths annually (World Health Organization,

2022). For this reason, and as a legal and quality re-

quirement for the dairy industry, controls must be per-

formed in various stages of the value chain and in all

batches of the final product. While pasteurization, a

crucial step in milk processing, significantly reduces

the risk of food-borne illnesses by eliminating most

harmful pathogens, it does not address certain con-

taminants, such as chemical residues like Aflatoxin-

M1 or residues from veterinary treatments, includ-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5088-9029

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5876-3922

c

https://orcid.org/0009-0005-3003-6519

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4344-4416

ing antibiotics (e.g., penicillin, enrofloxacin, sulfa-

doxine, streptomycin, trimethoprim, marbofloxacin).

The presence of such substances in raw milk is reg-

ulated in most countries and even minute quantities

will demand the discard of the milk (Olatoye et al.,

2016), due to the severity of the impact on human

health.

The diary industry uses laboratory methods such

as chromatography, immunoassays, and mass spec-

troscopy for the detection of Aflatoxin-M1 and an-

tibiotics residues in milk (Gaudin, 2017; Vercelli

et al., 2023; Getahun et al., 2023; Matabaro et al.,

2017). Despite their precise and quantitative analysis

of samples, these methods are time-consuming (up to

3 hours or even longer if outsourced), expensive and

require specialised staff. Furthermore, they are usu-

ally performed after milk is loaded onto transport ve-

hicles to dairy factories. Therefore, if a small portion

of the loaded milk is contaminated, the contamina-

tion will spread to the whole load leading to wasted

supply. Consequently, the financial losses to both

the farmers (penalties based on regulation for deliver-

64

Demosthenous, P., Aspri, M., Moyseos, M. and Sergides, M.

MILI: Biophotonics Technology for In-Situ, Fast, Accurate and Cost-Effective Milk Analysis.

DOI: 10.5220/0013130100003902

In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Photonics, Optics and Laser Technology (PHOTOPTICS 2025), pages 64-73

ISBN: 978-989-758-736-8; ISSN: 2184-4364

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

ing contaminated milk) and the receiving dairy facto-

ries (reduced milk quantities therefore production im-

pacts) are vast. Rapid screening methods, such as lat-

eral flow strips, can detect analytes within 10-40 min-

utes, but often generate a high rate of false positives

and lack specificity for different types of antibiotics

and in cases of positive results, a laboratory test con-

firmation is nevertheless needed, imposing additional

costs and delays. These factors increase the need for

the development of portable, highly integrated, and

cost-effective devices in the field of food quality con-

trol. State-of-the-art concepts such as electrochemi-

cal (Singh et al., 2023; Reinholds et al., 2015), opti-

cal (Gast

´

elum-Barrios et al., 2020; Yeh et al., 2017;

Surkova et al., 2023; Souroullas et al., 2024), lab-on-

a-chip (Buzzin et al., 2022; Manolis et al., 2024) tech-

niques are being employed to achieve this.

In this work, we present a device aiming to solve

these issues, through designing and developing a

novel method to simultaneously detect in less than 10

minutes, a selected panel of common milk contam-

inants for analysis at the farm (before loading con-

taminated milk for transportation) and at the receiv-

ing dairy industry level. The MILI device is based on

optical biosensors offering the analytical performance

of laboratory-based methods, at a cost comparable to

that of quick screening tests. The system is based on a

sensitive mini-fluorometer setup that monitors the sig-

nal from fluorescence emitting biosensors that specif-

ically bind on the selected analyte. The conceptual

biosensor (not presented here) consists of derivatiza-

tion and functionalization of a surface with antibod-

ies specific to the selected contaminants. The recom-

binant or the natural antigen is labelled with a fluo-

rophore and it is then mixed with the milk sample.

The resulting solution is then added to the functional-

ized surface and the competition between labelled and

unlabelled analytes inside the sample is evaluated by

the emitted fluorescence intensity i.e. decrease with

higher concentrations of the analyte in the sample

(Pennacchio et al., 2016). Here, the capability of the

device to detect contaminant concentrations dictated

by EU regulations translated to merely dye-molecules

or labelled antigens is demonstrated.

2 SYSTEM IMPLEMENTATION

This section describes: a) the system general archi-

tecture, b) the optical configuration, c) the overall in-

tegrated system, and d) the mobile application as the

graphical user interface.

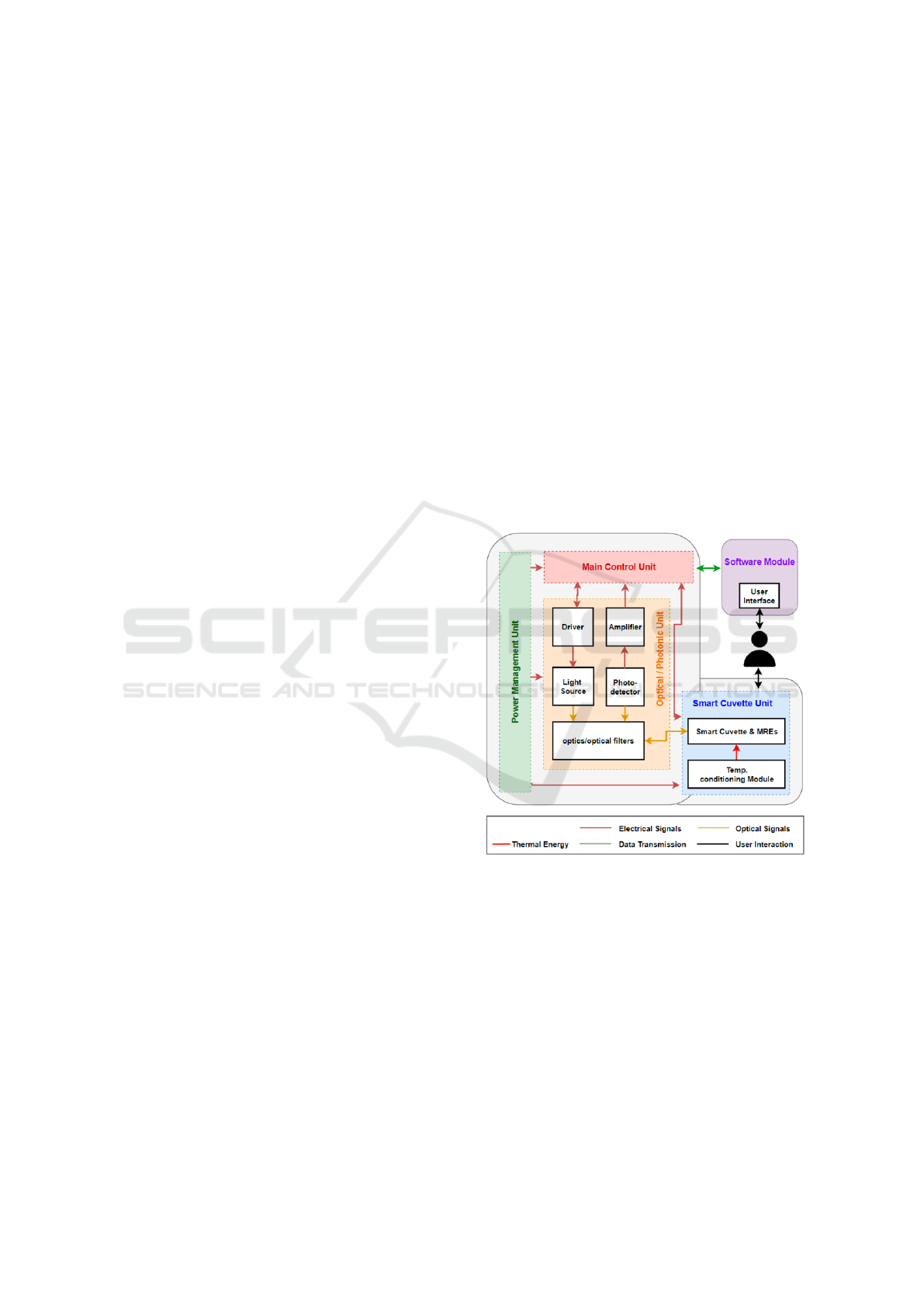

2.1 System Architecture

The general architecture of the MILI system presents

the different units/modules of the system (Figure 1),

as well as the user interaction that involves the man-

ual import of the milk sample, and the control of the

device and results visualisation via a mobile app. Fo-

cus is noted on the ‘Optical/Photonic Unit’ that con-

sists of the excitation light source, the photodetector

and the optical components, but also on the ‘Smart

Cuvette Unit’ that consists of a functionalised cu-

vette, and temperature conditioning module to keep

the sample at a stable temperature during measure-

ments. Moreover, the main control unit is responsible

for all system operations such as, controlling the exci-

tation light source, acquiring the data from the detec-

tor, performing basic calculations and transmitting the

analysis result to the mobile app. Finally, the power

management module is responsible to provide the re-

quired power supply to all different parts of the sys-

tem.

Figure 1: MILI System general architecture.

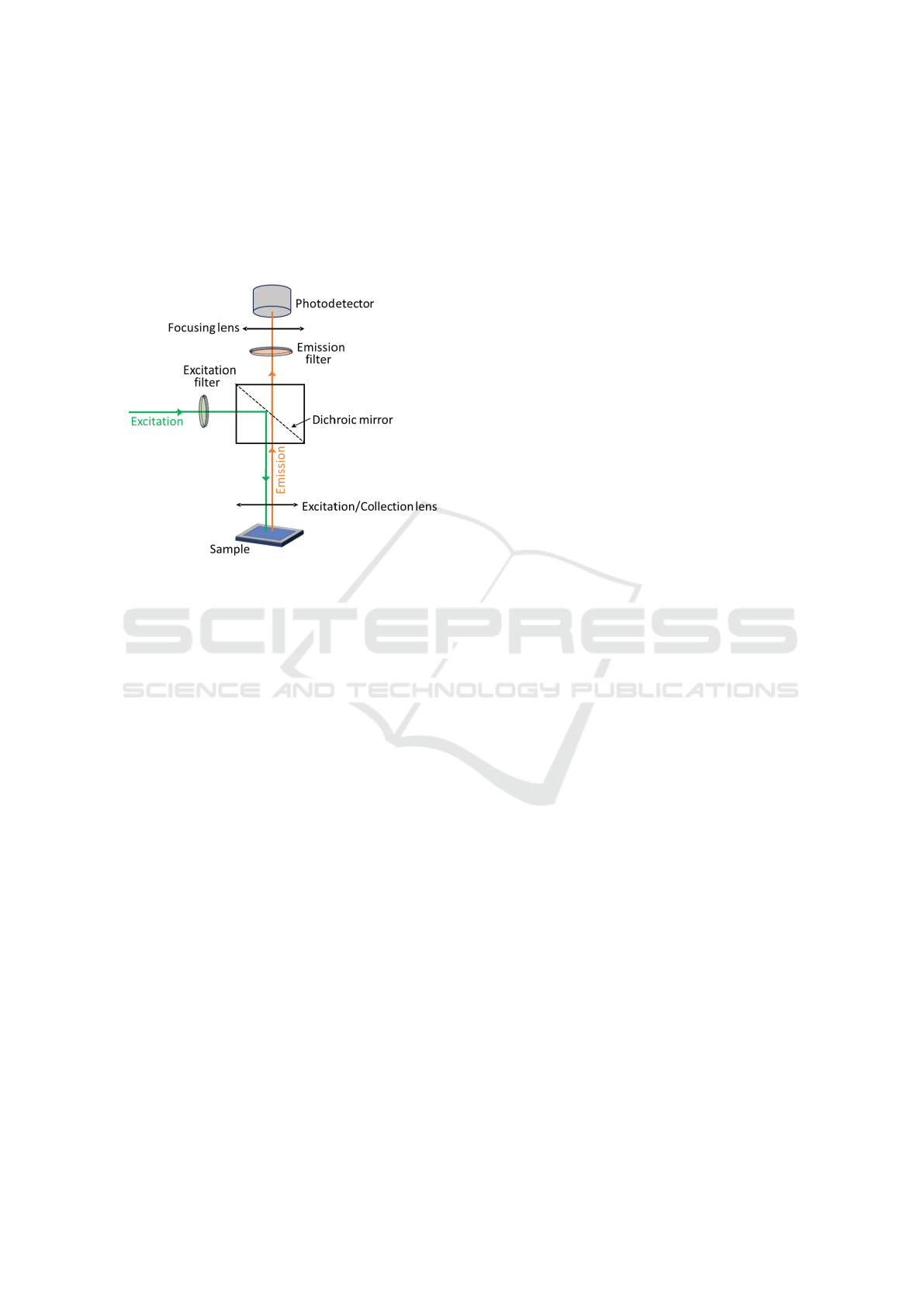

2.2 Optical Module

The optical configuration is based on a simple fluo-

rometer configuration (Figure 2) where light emitted

by the photo-excited sample can be measured. The

optical components were chosen as to excite and de-

tect fluorescence from specific dye molecules that are

widely used to label antibodies specific to the ana-

lytes of interest. The MILI mini-fluorometer appara-

tus has been developed and evaluated in two different

configurations which can be either used with the red

CF®568 or the cyanine-based far-red CF®647 fluo-

MILI: Biophotonics Technology for In-Situ, Fast, Accurate and Cost-Effective Milk Analysis

65

rescent dyes. This was done to account from possible

effects of the sample matrix when excited at differ-

ent wavelengths i.e., emission from the sample itself

which can shield the fluorophore signal. With this in

mind, the system was designed to allow for a straight-

forward and easy switch between different configura-

tions.

Figure 2: Fluorometer configuration. A light source excites

a fluorescent sample which in turn emits at a different wave-

length. The emitted light is then detected by a photodetec-

tor.

In order to achieve a satisfactory limit of detec-

tion (LOD) targeting 10 times less than the maximum

residue limits of EU regulations (Regulation 37/2010,

2010), relatively high excitation powers had to be

considered. This led to the use of a laser system as the

excitation source instead of a cheaper light emitting

diode (LED). Furthermore, due to the narrow band-

width and optimised beam profile laser systems usu-

ally offer, a high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) could be

achieved which is essential for the detection of low

fluorescence signals considered in these types of ap-

plications.

The experimental work conducted to validate the

optical setup’s capabilities and determine the lowest

detectable dye concentration and thus the estimate

the device’s LOD included dye molecules suspended

in Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) buffer to produce

concentrations ranging from 10 µM down to 0.1 pM.

In all work presented in this paper, the samples were

hosted in black-walled 96-well microplates suitable

for fluorescence-based assays. It is noted that fluo-

rescence emitted from samples of higher concentra-

tions and down to 10 nM was easily observed and dif-

ferentiated from background signal. For this reason,

and for the fact that concentrations higher than 10 nM

are irrelevant to the application in hand (outside of

the range set by EU regulations) results are presented

only for lower concentrations.

2.2.1 Red Fluorescent Dye

The first configuration involved the case where the an-

tibodies were to be labelled by a red fluorescent dye.

The selected dye in this case was CF®568 with ab-

sorption and emission maxima at 562 nm and 584

nm, respectively. It is noted that this labelling reagent

can be directly replaced by any of the following com-

mercially available fluorophores: Alexa Fluor®568,

ATTO 565, Rhodamine Red. Nevertheless, in this

case the secondary excitation peak of CF®568 at 532

nm was chosen since monochromatic sources at this

wavelength are more common and relatively cheaper.

Thus, a diode pumped solid state (DPSS) laser source

at 532 nm and maximum power of 40 mW was used

as the excitation source also eliminating the need for

a bandpass excitation filter due to its narrow linewidth

±1 nm.

The light from the excitation source is incident

on a single-edge dichroic mirror which reflects wave-

lengths below 550 nm. The reflected beam is then

guided through an achromatic triplet lens system

which focuses the beam on the sample area and also

used to collect and colimate the emitted light from

the sample. The emitted light then travels through

the dichroic mirror and passes through an additional

single-band emission filter centred at 580 nm thus

further filtering wavelengths outside the chromophore

emission range. Finally, the light is focused on to the

PMT detector by an additional lens.

In this case the laser diode was modulated at 1 kHz

allowing for a better visualisation of the difference be-

tween signal and background. The data collected dur-

ing experiments showed that the LOD achievable by

the device can be as low as 0.1 pM. Figure 3 shows

the obtained fluorescence signal for the range of dye

concentrations studied along with the modulation ap-

plied to the excitation source.

The obtained results highlight the capability of

the MILI device to detect low concentrations of dye

molecules (underestimate the LOD to 1 pM ∼ 0.0007

ppb for CF567 dye) which fall below the limits set

by EU regulations regarding antibiotics and toxins. It

can be safely assumed that this detection limit can be

applied to the suggested biosensing assay where op-

timally one dye molecule binds to a single antigen.

The effects of the milk matrix in real samples will be

discussed later.

PHOTOPTICS 2025 - 13th International Conference on Photonics, Optics and Laser Technology

66

Figure 3: Modulation and normalised emission signal as

recorded for CF568 diluted in PBS buffer solution for con-

centration range 0.1 – 1000 pM.

2.2.2 Cyanine-Based Far-Red Fluorescent Dye

The second configuration of the optical module

considers the case of cyanine-based far-red chro-

mophores also widely used in biosensing assays.

Namely, results presented here were obtained by us-

ing the CF®647 with absorption and emission max-

ima at 650 nm and 665 nm, respectively. Similarly

to the previous case, these dye molecules can be di-

rectly replaced by a set of other commercially avail-

able fluorophores such as Cy®5, Alexa Fluor®647,

DyLight®649. The laser source used in this configu-

ration has a nominal wavelength at 640 nm and max-

imum power of 35 mW.

The optics configuration is slightly modified from

the previous dye case. The single-edge dichroic mir-

ror now reflects wavelengths below 645 nm and an

additional single-band bandpass optical filter centred

at 642 nm is placed after the laser source to further

reduce unwanted background light. The triplet lens

system used for focusing the excitation beam and col-

lecting the emitted fluorescence remains unchanged.

The single-band emission filter is also switched to one

that is centred at 670 nm.

The experiments with different dye concentration

samples were repeated for this configuration. Figure

4 shows the signal recorded during these measure-

ments. In this case the excitation source was not mod-

ulated but instead the concentration axis was plotted

in logarithmic scale for a clearer representation. The

plotted values are the result of the averaging of mul-

tiple measurements. It is obvious that fluorescence

emission from the 0.01 pM sample can be differen-

tiated from the background signal coming from the

empty well or the PBS buffer sample. It should be

noted that 2500 mV is the maximum signal the spe-

cific PMT can output, with values higher than this

saturating the detector. For this reason, a combina-

tion of neutral density (ND) filters must be used in

cases of higher concentrations to avoid PMT satura-

tion even though this is not needed for this application

purposes.

Figure 4: Fluorescence signal for different CF647 dye con-

centrations (0.01 – 1000 pM) as recorded by the MILI de-

vice. “Empty” denotes background signal from an empty

well and “buffer” signal from merely PBS solution. The y-

axis is in logarithmic scale.

2.3 System Integration

The device components are shown in Figure 5, con-

sisting of the following main electronics parts: a)

main control unit (MCU) with Bluetooth 5.0 connec-

tivity, b) temperature controller with Peltier heat ele-

ment and PT1000 temperature sensor for condition-

ing the sample’s temperature around 30 °C, c) de-

vice powering via four Li-Ion rechargeable batteries

to extent the device operating hours (approximately 8

hours of continuous operation), d) a power bank mod-

ule for charging the Li-Ion batteries via 5V USB, e)

a DC/DC voltage converter (from 5V to ±5V) for op-

erating the PMT detector, and e) a DC/DC voltage

converter (from 5V to 12V) for operating the laser.

Upon validating the optical configuration, the sys-

tem was integrated to combine all modules (elec-

tronic, network, etc) and placed in an enclosure. The

integrated MILI prototype device encapsulated in the

custom 3D-printed black PLA material is presented

in Figure 6, demonstrating a portable device for milk

analysis capable of detection of contaminants in raw

milk samples. It uses a single vial, detached from a

black walled 96-well strip, as the sample-cuvette for

performing analysis on 200 µl of buffer-diluted raw

milk samples. It has dimensions of 183 mm x 56 mm

MILI: Biophotonics Technology for In-Situ, Fast, Accurate and Cost-Effective Milk Analysis

67

Figure 5: The integrated MILI prototype device in a custom

3D-printed housing.

Figure 6: The MILI prototype device as a portable device

for milk analysis.

x 230 mm and weights 1.3 kg.

2.4 Mobile Application: Graphical User

Interface

A mobile application was developed for the control

and visualisation of the analysis procedure (Figure 7).

The application can automatically search and connect

to a preconfigured (known MAC address) BLE de-

vice. Furthermore, the MCU is configured with a

control-firmware to execute sequentially the follow-

ing procedures for every analysis run: a) the MCU-

Bluetooth (BLE) is advertising until a connection is

established with the mobile application, b) the MCU

waits for a BLE request via the ‘Run Test’ button

on the mobile app graphical user interface (GUI), c)

upon analysis request, a counter runs for a minute

to allow the sample to reach a constant temperature

at 30 °C, d) 10000 measurements are acquired from

the PMT at a sampling rate of 1 Hz prior to switch-

ing on the laser; the average of these measurements

represents the background or noise value, e) the laser

switches ON and the system waits for 3 seconds to

stabilize, f) 10000 measurements are acquired from

the PMT at a sampling rate 1 Hz; the average of these

measurements represents the milk-analysis signal, g)

the MCU sends the result of the analysis in the form

of ’positive’ or ’negative’ to the mobile app via the

BLE connection and then the device is ready for the

next analysis, where procedures c-g will be executed

again.

Figure 7: MILI mobile application used as the graphical

user interface for control and visualisation of an analysis.

For the proper operation of the device, the user

needs to follow the step-by-step instructions: a) Run

the ‘MILI app’ and switch ON the MILI device. The

device should be connected immediately with the mo-

bile app and the green LED on the device left side

will stop flashing periodically and will remain on; this

confirms that the connectivity has been established

PHOTOPTICS 2025 - 13th International Conference on Photonics, Optics and Laser Technology

68

successfully, b) proceed to loading the sample-cuvette

and press the ‘Run Test’ button on the application

GUI, c) wait for approximately 2 minutes and press

the ‘View Results’ button when it appears to view

the results, d) access the menu on the bottom of the

screen to check the historical and statistical results of

the analysis (Figure 7).

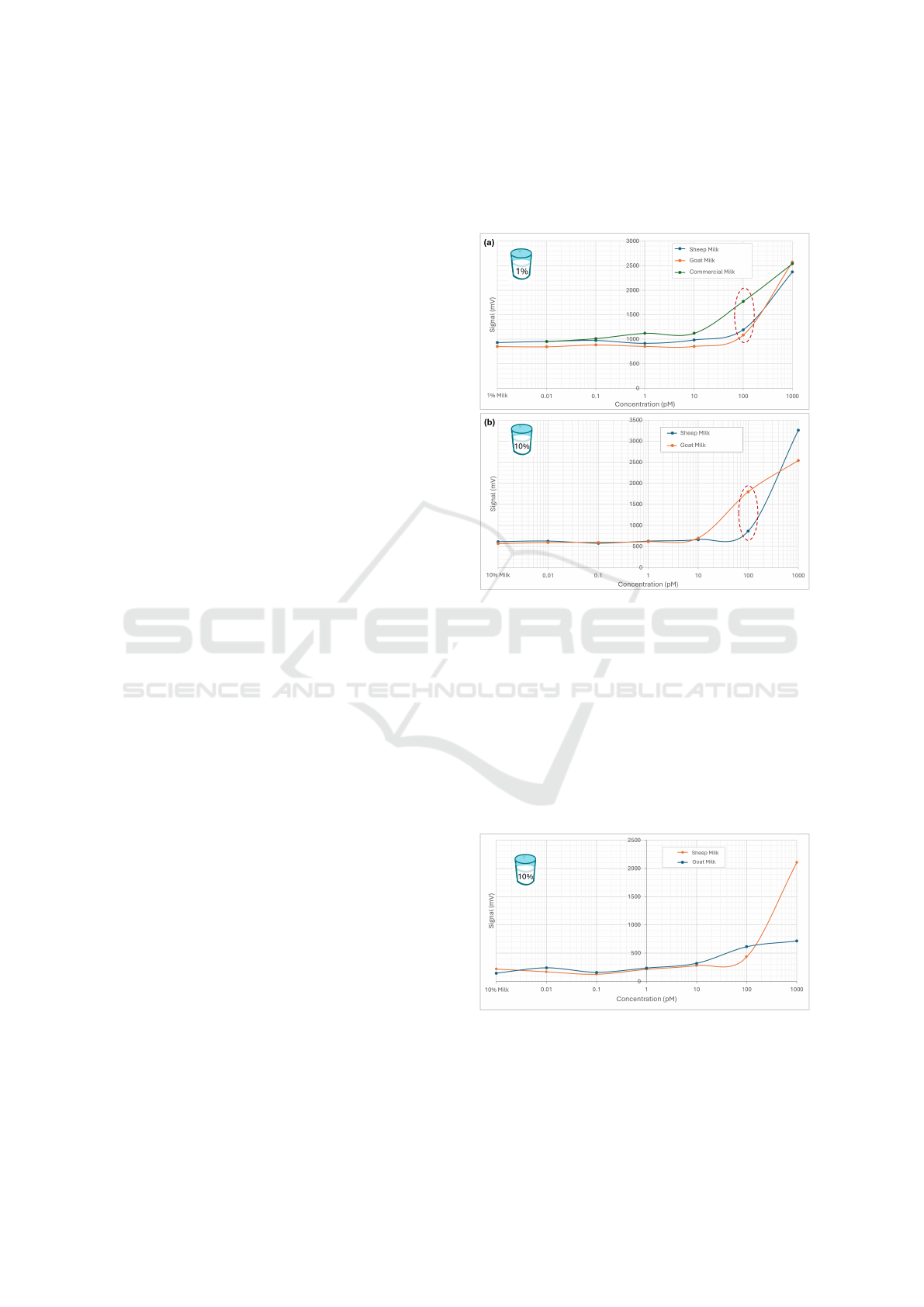

3 PRELIMINARY TESTING

The MILI prototype has been tested for its functional-

ity and general behaviour in different conditions such

as: a) use of different types of sample-cuvettes: clear

and black. Black cuvettes are more suitable for fluo-

rescence measurements, while clear cuvettes are eas-

ily accessible, b) use with different types of milk sam-

ples: raw sheep, goat, cow as well as commercially

available cow milk (milk fat content is considered as

a variable parameter in the different milk types, which

in some cases affects the results), c) use of different

dilution of milk in PBS buffer i.e. 1% and 10% (this

was based on previous experiments showing that 1%

milk-buffer exhibits lower absorption of the excitation

wavelength, while 10% aims at reduced dilution of

the milk, resulting to higher analyte concentration in

the sample), d) use of different fluorescent molecules

i.e. CF647 molecules for calibration and characterisa-

tion purposes, and labelled penicillin-G (PenG) with

CF647 simulating the analysis assay. The following

experiments employ clear cuvettes with 1% and 10%

milk-buffer samples, and three different milk types:

goat, sheep, and commercially available milk, spiked

with different CF647 dye concentrations. The re-

sults show higher background signal in the case of

1% milk-buffer (∼1000 mV) (Figure 8a) compared to

10% (∼600 mV) (Figure 8b). This is most likely due

to increased reflection of the excitation light from the

clear-cuvette walls, combined with the lower absorp-

tion from the milk matrix, resulting to a higher de-

tectable background signal. The minimum detectable

concentration is 100 pM especially in the case of 10%

milk-buffer, where the background signal is lower.

The worsening of the detectable limit compared to the

results obtained prior integration is due to a combina-

tion of the effects originating from the milk matrix

and use of compact electronics used to drive the inte-

grated system in contrast with the transparent buffer

solution and the more expensive laboratory equip-

ment used during the evaluation experiments. More-

over, sheep milk has a higher fat content than goat

milk which causes a lower fluorescence signal for the

100 pM dye-concentration, since fat further absorbs

the excitation light, which in turn reduces photolumi-

nescence. Analogous behaviour is presented in the

case of the commercial milk (Figure 8a), which con-

tains less fat than both raw sheep and goat milk, there-

fore higher fluorescence signal is induced.

Figure 8: Tests with clear cuvettes and milk samples with

(a) 1% and (b) 10% milk:buffer spiked with different CF

647 dye concentrations.

Based on the above results, 10% milk-to-buffer

ratio was used for the following experiments, where

black cuvettes were tested. As expected, black cu-

vettes showed lower background signal, which in turn

made the 10 pM dye concentration observable. On

the other hand, 1 pM dye concentration can be barely

considered detectable, since the voltage difference

from the background signal almost falls within the

signal noise level (∼30mV).

Figure 9: Tests with black cuvettes and 10% milk-buffer

solutions at different dyes concentrations.

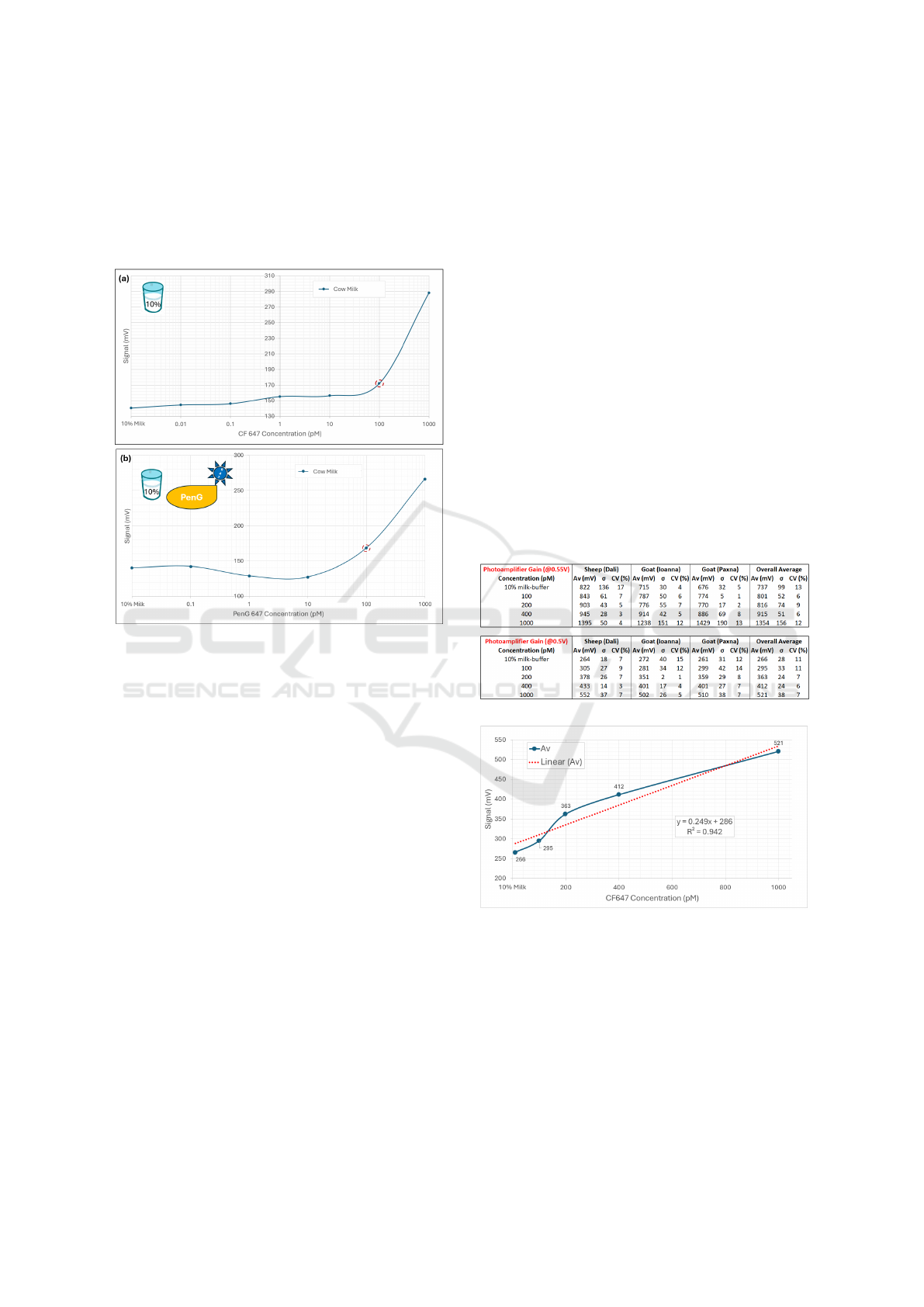

The next experiments used raw cow milk. Simi-

larly, 10% milk-buffer samples have been tested (Fig-

ure 10a), while this time labelled PenG (PenG647)

MILI: Biophotonics Technology for In-Situ, Fast, Accurate and Cost-Effective Milk Analysis

69

was also used to spike the samples (Figure 10b). This

was done to better simulate the real analysis assay

where the analyte is PenG. Similar results with the

other types of milk were obtained even with PenG647,

with the 100 pM concentration being distinguishable

from background in all cases.

Figure 10: Tests with black cuvettes and raw cow milk with

a) 10% milk-buffer at different CF647 concentrations, and

b) spiked with PenG labelled with CF647.

4 PERFORMANCE EVALUATION

For the next step of the validation process, more ex-

periments defining the performance aspects of the

prototype such as, the repeatability, reproducibility,

accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity were conducted.

Moreover, during these experiments the device was

tested under different amplification settings on the

photodetector, in order to change the dynamic range

during measurements to the range of the interest, and

thus detect dye concentrations up to 1000 pM.

For validating the repeatability and reproducibil-

ity, and hence the precision of measurement, tests

were repeated multiple times on spiked milk samples

(100, 200, 400, 1000 pM dye concentrations) col-

lected from different batches and farms. It is noted

that for each measurement performed the sample was

removed from the device and placed again to check

how user manual sample positioning affects the re-

sults. Furthermore, two different amplification set-

tings on the photodetector were tested: 0.5V and

0.55V as the control voltage for the dedicated gains.

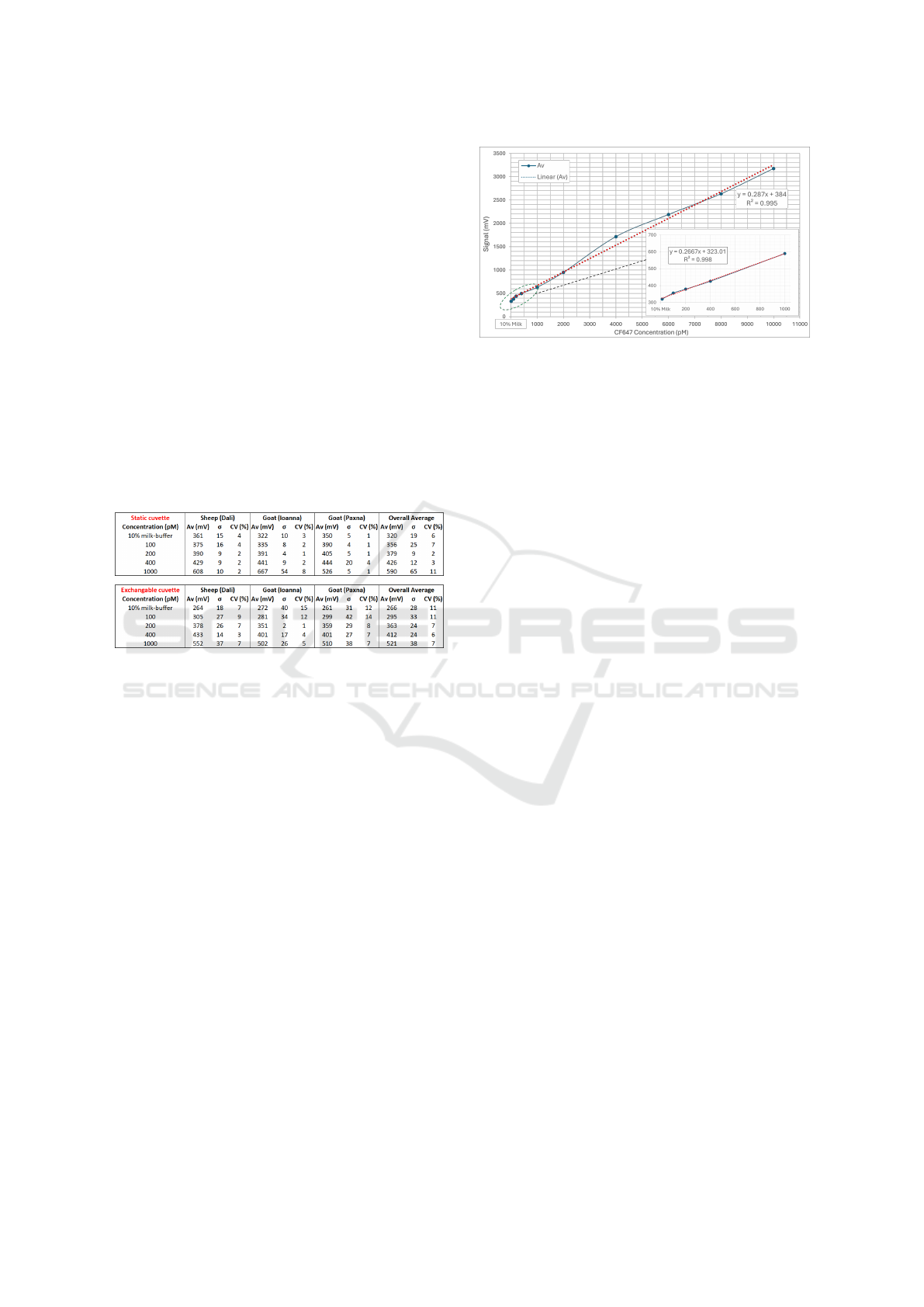

The results of these measurements are concluded

in Table 1, that includes the calculated average value,

Av, standard deviation,σ, and coefficient of variation,

CV for three different batches of milk at different

dye-CF647 concentrations, as well as the overall av-

erage including all three types of milk. A relatively

low ‘Coefficient of Variation’ has been acquired for

all measurements, being below 20% which in general

is considered as a ‘Very good’ and acceptable value.

Furthermore, 2-3 times lower σ was observed (Ta-

ble 1) when the photo-amplification was set at 0.5V

opposed to the results with the higher amplification

at 0.55V, which it was expected due to the increase

of the photodetector noise with the increase of its

amplification. Moreover, both amplification settings

showed good linear behaviour (Figure 11), with R

2

values to be higher than 0.9 which shows strong rela-

tion to a linear expression.

Table 1: Tests results for validating the repeatability and

the reproducibility of the measurement. The names in the

parenthesis next to the animal type is the location of the

farm the milk was collected from.

Figure 11: 10% raw cow milk-buffer spiked with CF647

at different concentrations, using detector amplification at

0.5V control voltage. Cuvette was repositioned before each

measurement. The dashed line represents the linear fitting.

Subsequently, similar experiments with fresh-

prepared samples were conducted, using photo-

amplification at 0.5V control voltage. Again, each

measurement was repeated several times for each con-

centration, but this time the sample was placed in

the holder and the following measurements were ex-

ecuted one after the other without repositioning the

PHOTOPTICS 2025 - 13th International Conference on Photonics, Optics and Laser Technology

70

sample. This way, the experiment generated results

on the reproducibility but also on the robustness of

the measurement, correlated to the sample positioning

executed by the user. Table 2 includes the previous

(exchanging the cuvette) and the current (static cu-

vette) results for comparison. A general observation

is that the standard deviation, σ, and consequently

CV are only slightly lower in the case where the cu-

vette was static. Therefore, it can be considered that

these results verify high measurement reproducibility

and robustness related to sample positioning. In other

words, the mechanical interface between the sample-

holder and the optical apparatus, ensures reproducible

results when it comes to the sample positioning prac-

tice applied by the user. Furthermore, the highly re-

peatable results (low σ and CV <10%) in the case of

the static-cuvette, show high measurement stability.

Table 2: Tests results for validating the reproducibility and

robustness of the sample-positioning.

Similarly, linear fitting was applied to the results

as shown in Figure 12 , to verify consistency with the

previous results obtaining a higher R

2

value equal to

0.998. Moreover, the flexibility of using the dynamic

range for measuring higher concentration allowed for

a quick test up to 10000 pM (10 nM), in order to

check linearity at higher dye concentrations. The re-

sults are shown in Figure 12, where again the data are

described by a linear relation with an R

2

value close

to unity.

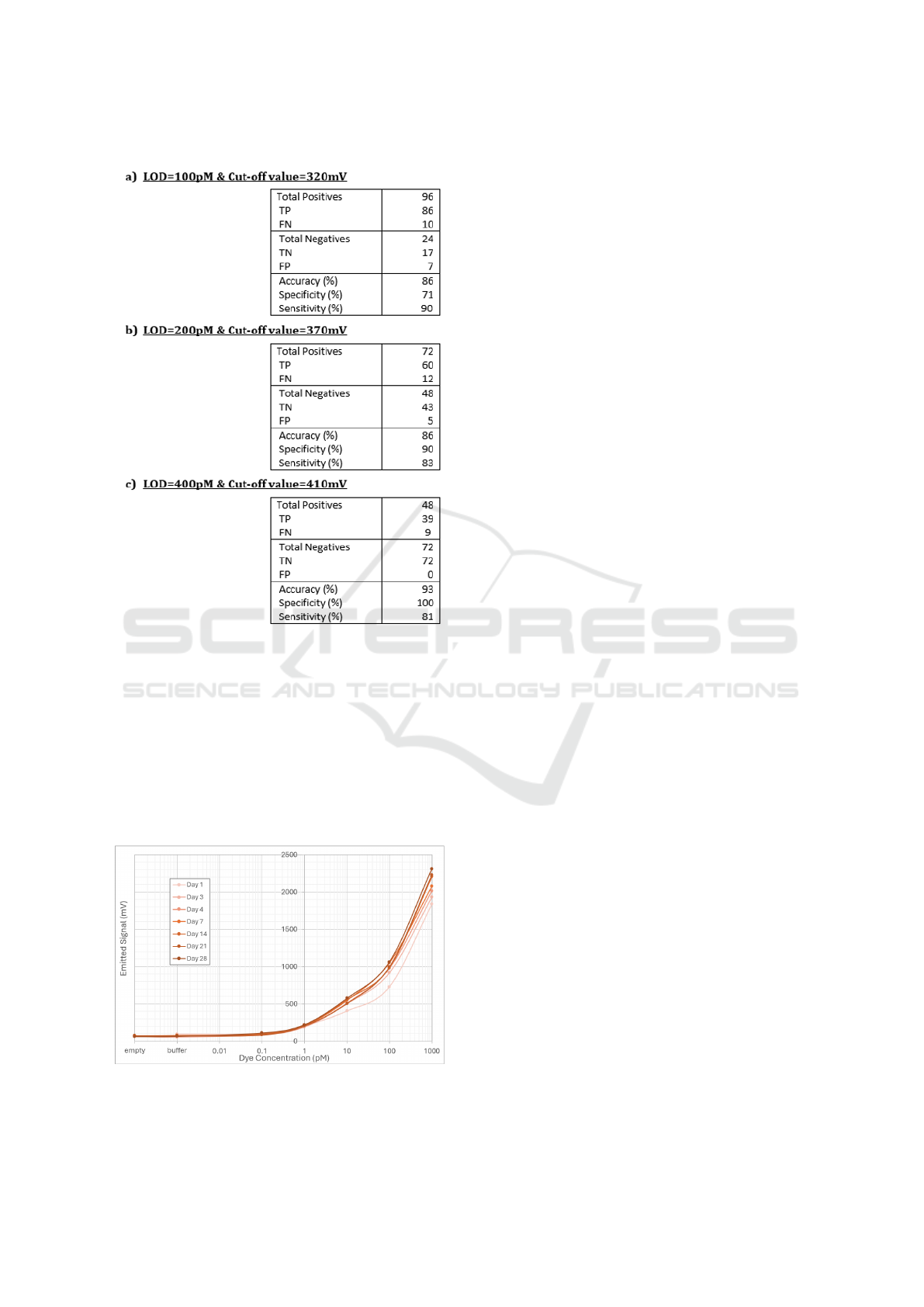

Finally, the device performance in terms of ac-

curacy, sensitivity and specificity was defined. Data

from 120 tests (24 samples for each concentration –

0 pM, 100 pM, 200 pM, 400 pM, 1000 pM) in to-

tal were used to define true positives, TP, false nega-

tives, FN, true negatives, TN, and false positives, FP.

The same data was also used to calculate the above

performance indicators based on the defined LOD (or

cut-off value). Emphasis should be given in the def-

inition of the LOD, considering that raw milk sam-

ples undergone 10% dilution, resulting to an analyte

concentration of 10-times lower than in the initial raw

sample. This means that the 100 pM, 200 pM and 400

pM referred LODs, correspond to 1 nM (∼1 ppb), 2

nM(∼2 ppb) and 4 nM(∼4 ppb) concentrations in raw

Figure 12: 10% raw cow milk-buffer spiked with CF647

at different concentrations. Cuvette position remained un-

changed throughout data set. Inset: zoom in for dye con-

centrations below 1 nM. The red dashed line represents the

linear fitting.

milk respectively. Satisfactory performance results

(>80%) are presented in Table 3 for three different

defined LODs. All three LODs present very good de-

tection accuracy higher than 85%, while in each case

sensitivity (related to FN) competes specificity (re-

lated to FP) and vice versa. Specifically, when requir-

ing high sensitivity thus sacrificing specificity, LOD

at 100 pM is preferable, while when requiring the op-

posite, LOD at 400 pM seems ideal with 100% speci-

ficity. In the case where a compromise is required,

then an LOD at 200 pM gives sufficient performance

values, between 83-90%. It is noted that the LOD

values obtained by these validation experiments are

comparable to other current works in the area of milk

contaminant detection (Matabaro et al., 2017; Jalili

et al., 2020).

Finally, in order to identify the integrity of the se-

lected dye molecules for labelling the antibodies over

time, a series of experiments was conducted to mea-

sure the emitted PL signal after storage. This work

was performed as part of the optical configuration de-

velopment to get an indication on the repeatability of

the device in measuring identical samples at differ-

ent points of time. Furthermore, the data collected

here serve as a suggestion for the expiry period of the

biosensors in terms of a consumable product in case

of market exploitation. The degradation experiments

consisted of different dye concentration samples pre-

pared and assessed in different time intervals within a

month to validate their integrity over time. The sam-

ples were prepared and stored at T = 5 °C until the

following measurement. Initially the measurements

were performed after a few days apart and then per-

formed weekly (Figure 13). Furthermore, new sam-

ples were prepared after 15 and 20 days from the

initial preparation and the emitted signal was com-

pared between old and new samples (not shown here).

These experiments revealed a satisfactory consistency

MILI: Biophotonics Technology for In-Situ, Fast, Accurate and Cost-Effective Milk Analysis

71

Table 3: Performance indicators based on defined LOD.

of fluorescence signal collected from the samples at

different times. The small increase in signal that was

observed between measurements comes from the fact

that the buffer solution precipitated on the parafilm

used to seal the samples during storage, thus slightly

increasing the overall dye concentration. These re-

sults lead to the conclusions that (a) the device is ca-

pable of repeated measurements with high accuracy

and (b) the choice of the labelling reagents is suitable

for at least up to a month before mixing with real ma-

trix samples.

Figure 13: Degradation experiments for different concen-

trations of CF567 at different time intervals.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the MILI device different modules

have been described in detail and validation experi-

ments and their outcomes have been discussed. The

optical module performed in a satisfactory fashion

providing evidence for detection capabilities which

allow for the recognition of contaminants (when

bound to labelled antibodies) in concentrations that

fall within the limits imposed by EU regulations. Fur-

thermore, based on a comprehensive preliminary test-

ing and performance evaluation of the MILI proto-

type, the results demonstrate that the device can re-

liably detect low concentrations of chromophores in

various milk samples, with repeatability and robust-

ness confirmed under different conditions. Overall,

the device showed promising accuracy, and a LOD

within the regulatory requirements for Penicillin-G

detection in milk. These findings confirm that the

MILI prototype is a potential tool for effective milk

safety monitoring, meeting the targeted detection lim-

its while maintaining high measurement consistency.

The proposed technology aims to achieve a quality

level of analysis equivalent to that provided by labora-

tories, without the need for trained personnel, provid-

ing results within 10 minutes and with costs that are

significantly lower than those of the current market-

available solutions. Overall, the MILI system seeks

to reduce costs and improve contamination detection,

offering a practical solution for early intervention and

minimizing health risks and financial losses in the

dairy supply chain.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The work was supported by the Cyprus

Research and Innovation Foundation grant

EXCELLENCE/0421/0188 which is co-financed

by the European Regional Development Fund

and the Republic of Cyprus and by the European

Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation

programme ”Code:Refarm” under grant agreement

No 101000216.

REFERENCES

Buzzin, A., Asquini, R., Caputo, D., and de Cesare, G.

(2022). Evanescent waveguide lab-on-chip for opti-

cal biosensing in food quality control. Photon. Res.,

10(6):1453–1461.

Fukuda, K. (2015). Food safety in a globalized world. Bull

World Health Organ, 93(4):212.

PHOTOPTICS 2025 - 13th International Conference on Photonics, Optics and Laser Technology

72

Gast

´

elum-Barrios, A., Soto-Zaraz

´

ua, G. M., Escamilla-

Garc

´

ıa, A., Toledano-Ayala, M., Mac

´

ıas-Bobadilla,

G., and Jauregui-Vazquez, D. (2020). Optical methods

based on ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared spectra

to estimate fat and protein in raw milk: A review. Sen-

sors, 20(12).

Gaudin, V. (2017). Advances in biosensor development for

the screening of antibiotic residues in food products of

animal origin – a comprehensive review. Biosensors

and Bioelectronics, 90:363–377.

Getahun, M., Abebe, R. B., Sendekie, A. K., Woldeyoha-

nis, A. E., and Kasahun, A. E. (2023). Evaluation of

antibiotics residues in milk and meat using different

analytical methods. International Journal of Analyti-

cal Chemistry, 2023(1):4380261.

Jalili, R., Khataee, A., Rashidi, M.-R., and Razmjou, A.

(2020). Detection of penicillin g residues in milk

based on dual-emission carbon dots and molecularly

imprinted polymers. Food Chemistry, 314:126172.

Manolis, A., Eleftheriou, C., Elrabiaey, M. A., Tsekenis,

G., D’Auria, S., Varriale, A., Capo, A., Staiano, M.,

Chmielak, B., Schall-Giesecke, A. L., Suckow, S., and

Tsiokos, D. (2024). Ultra-fast detection of pathogens

and protein biomarkers using a low-cost silicon plas-

monic biosensing platform. Sensors and Actuators

Reports, 8:100221.

Matabaro, E., Ishimwe, N., Uwimbabazi, E., and Lee,

B. H. (2017). Current immunoassay methods for the

rapid detection of aflatoxin in milk and dairy prod-

ucts. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and

Food Safety, 16(5):808–820.

Olatoye, I. O., Daniel, O. F., and Ishola, S. A. (2016).

Screening of antibiotics and chemical analysis of

penicillin residue in fresh milk and traditional dairy

products in Oyo state, Nigeria. Vet World, 9(9):948–

954.

Pennacchio, A., Varriale, A., Scala, A., Marzullo, V. M.,

Staiano, M., and D’Auria, S. (2016). A novel fluo-

rescence polarization assay for determination of peni-

cillin g in milk. Food Chemistry, 190:381–385.

Regulation 37/2010 (2010). Commission Regulation (EU)

No 37/2010 of 22 December 2009 on pharmaco-

logically active substances and their classification

regarding maximum residue limits in foodstuffs of

animal origin.

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/

?uri=celex%3A32010R0037.

Reinholds, I., Bartkevics, V., Silvis, I. C., van Ruth, S. M.,

and Esslinger, S. (2015). Analytical techniques com-

bined with chemometrics for authentication and de-

termination of contaminants in condiments: A review.

Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 44:56–72.

Singh, B., Bhat, A., Dutta, L., Pati, K. R., Korpan, Y., and

Dahiya, I. (2023). Electrochemical biosensors for the

detection of antibiotics in milk: Recent trends and fu-

ture perspectives. Biosensors, 13(9).

Souroullas, K., Manoli, A., Itskos, G., Apostolou, T., and

Papademas, P. (2024). Fluorescence of intrinsic milk

chromophores as a novel verification method of uv-c

treatment of milk. Foods, 13(18).

Surkova, A., Bogomolov, A., Paderina, A., Khistiaeva, V.,

Boichenko, E., Grachova, E., and Kirsanov, D. (2023).

Milk analysis using a new optical multisensor system

based on lanthanide(iii) complexes. Engineering Pro-

ceedings, 48(1).

Vercelli, C., Amadori, M., Gambino, G., and Re, G. (2023).

A review on the most frequently used methods to de-

tect antibiotic residues in bovine raw milk. Interna-

tional Dairy Journal, 144:105695.

World Health Organization (2015). WHO estimates of

the global burden of foodborne diseases: food-

borne diseases burden epidemiology reference group

2007–2015.

World Health Organization (2022). Food safety.

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/

food-safety.

Yeh, P., Yeh, N., Lee, C.-H., and Ding, T.-J. (2017). Appli-

cations of leds in optical sensors and chemical sens-

ing device for detection of biochemicals, heavy met-

als, and environmental nutrients. Renewable and Sus-

tainable Energy Reviews, 75:461–468.

MILI: Biophotonics Technology for In-Situ, Fast, Accurate and Cost-Effective Milk Analysis

73