Modeling for Assessment of Risks in Smart City Mobility Operations

Reem Al Sharif

a

and Shaligram Pokharel

b

Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar

Keywords: Smart City, Operation Phase Risks, Smart Mobility, Smart Transportation Applications,

Risk Assessment Models.

Abstract: Smart city operations face risks due to project complexity and the involvement of multiple stakeholders. Such

risks include cybersecurity, data security and privacy, system interoperability, maintenance of smart

technology, shortage of trained experts, complicated governance, and stakeholder engagement challenges.

Assessing these risks is vital to ensure the availability and efficiency of smart city services, support reputation,

and sustain revenue. Existing assessment tools evaluate smart cities' operational smartness, sustainability, and

management but often lack comprehensiveness in risk assessment. This paper contributes by proposing a risk

assessment model using the Dempster-Shafer theory that can consider a full spectrum of risks in smart city

operations. The model is evaluated on preliminary operational data from a smart transportation system in

Qatar, and key operational phase risks in smart mobility are assessed.

1 INTRODUCTION

A smart city aims to enhance citizens' quality of life,

support the economy, resolve various urban

problems, such as transportation and traffic

congestion, foster a sustainable environment, and

facilitate interaction with government authorities

(Ismagilova et al., 2019; Sharif & Pokharel, 2021)

To achieve these goals, proper communication,

involvement, and active contribution from smart city

stakeholders are crucial (Hasija et al., 2020).

Accordingly, smart city operation requires constant

stakeholder communication to gather and access smart

city's citizens' usage of services, which will support

demand estimation, enhance provided services, and

identify implementation challenges and risks.

Also, during operation, interoperability between

digital platforms, operation processes, and incentive

mechanisms is considered (Hasija et al., 2020).

Smart city operation is exposed to different risks

due to the complexity of the smart city project and the

multiple engaged stakeholders (Sharif & Pokharel,

2021).

The risks can be grouped into technological risks,

such as cybersecurity, data security and privacy,

system interoperability, and lack of maintenance of

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7565-1527

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7709-7803

smart technology (Shayan et al., 2020)., and non-

technology risks such as scarce trained and

specialized smart city experts, complicated

governance, and stakeholders' engagement

challenges (Shayan et al., 2020). These risks affect

the availability and efficiency of services.

Assessment tools are introduced by different

authors to assess risks related to the operation,

sustainability, or management ( Deveci et al., 2020;

Fernandez-Anez et al., 2018; Patrão et al., 2020 ).

However, these assessment tools are not

comprehensive (Alawad et al.2020; Dimitriadis et al.

,2020;Domingos et al., 2008) as they focus mainly on

technology risks independently from non-technical

risks (Singh & Helfert, 2019).Regarding operation,

which is the focus of this paper, risks become

interrelated and affect performance (Zheng et al.,

2020).

This paper proposes a risk assessment model by

considering technical and non-technical risks during

the operation phase of smart mobility. The model

assesses risks using the Dempster-Shafer (DS) theory.

The paper contributes by proposing a risk

assessment model for smart cities. The model is

generic and is able to include a wide spectrum of

246

Al Sharif, R. and Pokharel, S.

Modeling for Assessment of Risks in Smart City Mobility Operations.

DOI: 10.5220/0013155500003893

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems (ICORES 2025), pages 246-254

ISBN: 978-989-758-732-0; ISSN: 2184-4372

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

technical and non-technical risks across smart city

project operational phase.

Therefore, the following research questions are

addressed in this paper.

RQ1: What are the main operation phase risks in

smart mobility?

RQ2: How can a smart city risk assessment model be

applied to smart mobility application data?

Further discussion in this paper is organized as

follows: literature review in Section 2. Smart mobility

data is provided in Section 3. Section 4 discusses the

outcome of the analysis, and Section 5 provides the

conclusions.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

This section illustrates the literature research on the

smart mobility dimension in smart cities, operational

phase risks, and risk assessment tools and models.

2.1 Smart Mobility

Smart mobility is the main dimension of a smart city

that solves common transportation issues(Sharif &

Pokharel, 2021). Technology can support integrated

mobility (Porru et al., 2020).

The technologies that enable smart mobility

include AI, IoT, big data, and blockchain (Paiva et al.,

2021). Smart mobility should aim to use autonomous

vehicles and provide coordinated choices for people

to ease commutation (Appio et al., 2019). The

communication between autonomous cars and smart

mobility is achieved through IoT devices that collect

real-time decision-making data (Silva et al., 2018).

The ability to communicate among the vehicles

through IoT makes it the Internet of Vehicles (IoV),

which allows communication between vehicles and

helps to support traffic safety, efficiency, and smart

mobility (Ismagilova et al., 2019).

The risks associated with smart mobility

applications are the unavailability of network and

sensors' connectivity (Porru et al., 2020), problems

with security and privacy of mobility as a service

application (Paiva et al., 2021), the unavailability of

real-time connectivity and data analytics to use crowd

smart applications(Tao, 2013). These risks need

consideration during the planning and operation of

smart mobility applications (Ullah et al., 2021).

2.2 Risks Related to Smart Mobility

During Operation

During the operation, smart mobility applications are

vulnerable to multiple risks, such as legal, financial,

governance, and technical resources. In addition to

technological risks such as security, interoperability,

network connections, and data privacy (Oladimeji et

al., 2023). A study by Alanazi & Alenezi (2024)

identified major risks in smart mobility applications,

specifically in smart transportation systems: lack of

standards, which will lead to interoperability

challenges when connecting different applications,

and risks related to stakeholders' collaboration and

engagement.

The study provided multiple interoperability

issues related to the layers of the traffic management

system and proposed an interoperability platform

requirement to overcome challenges and risks.

Another study by Lacinák (2021) categorized

risks related to smart transportation systems as risks

related to personal level, such as cyber-attacks and

data privacy. Risks related to the community level,

namely outdated technology infrastructure and

insufficient network connections. Other risk

categories are related to economic levels like

untenable pricing policies, design levels such as

inadequate infrastructure, and strategy levels related

to users' culture change in smart transportation

systems (Lacinák, 2021).

Studies highlight cybersecurity as a significant

risk associated with IoT technology, which is

considered a main building block of smart mobility

applications (Lee, 2020; Ande et al., 2020).

Addressing smart mobility risks requires a robust

legislation and governance framework to set

standards, policies, and guidelines to provide

solutions to technology and non-technology-related

challenges of operating smart transportation systems

and other smart mobility applications (Suthanthira

Vanitha et al., 2021).

2.3 Risk Assessment Tools and Models

Dimitriadis et al. (2020) developed a cybersecurity

risk assessment tool that uses a conjunction of the

OCTAVE approach (for identification, analysis, and

prioritization) and MAGERIT approach (for

identification, analysis, and mitigation and

specifically utilized for communication-related risks)

for a computerized risk assessment in smart sensor

environments. The tool deploys existing standards

and platforms and extracts attack patterns to evaluate

Modeling for Assessment of Risks in Smart City Mobility Operations

247

risks in the automated systems used in smart city

dimensions.

Another tool is the Smart City KPI-guided

Security tool proposed by Ye et al. (2023). The tool

and applications; however, this model is useful for the

design phase of a smart city.

Ullah (2018) proposed a risk index model. The

author applied linear estimation, hierarchical fuzzy

logic, and a composite model to evaluate the risk

index. This model focuses on underground locations

and clustered risk factors to develop a risk index to

prioritize underground locations (Ullah, 2018).

Alawad et al. (2020) proposed a smart mobility

risk assessment model by considering railway

applications. The model evaluates and controls

security and safety risks within railway operations.

The model uses an adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference

system (ANFIS) and artificial neural networks

(ANN) to train an AI model to improve the accuracy

of the risk projections, learning, and capturing actual-

time risk levels. However, the model assumes

linearity of inputs and risk assessment and requires

time for the artificial neural network training.

The use of AI and machine learning for risk

assessment is proposed by (Sharma & Singh, 2022).

The tool is expected to help identify and predict future

risks.

3 RESEARCH DESIGN

This section provides the research method, data

collection, the proposed risk assessment model for

smart cities, and the application of smart mobility

operations risks.

3.1 Research Method

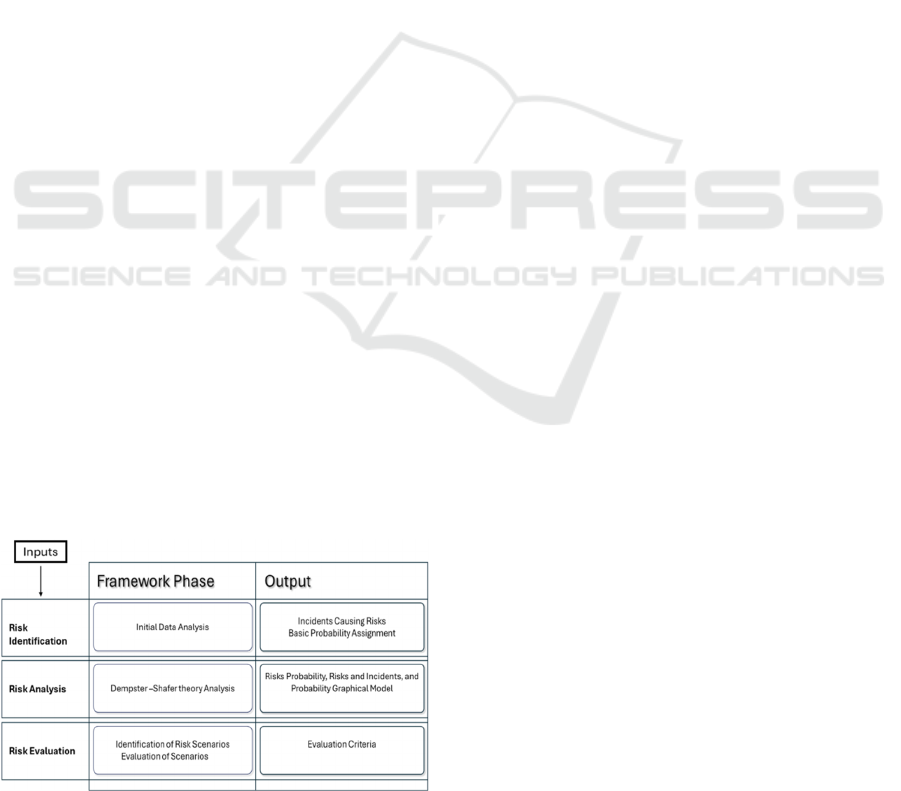

Figure 1 will illustrate the proposed risk assessment

model for smart cities, which will be detailed in the

following paragraphs:

3.1.1 Inputs

Initial data is collected through interviews with

experts and a review of the risk register.

3.1.2 Risk Identification

Initial data is analyzed as follows:

a. Risk incidents are ranked during the interviews.

The interview scripts are studied; challenges and

incidents causing risks are denoted by (I).

b. The data is further streamlined to name subjects

of risk, essentially leading to a basic probability

assignment (the probability of a risk to occur),

represented by (m), for the likelihood of an

incident leading to risk.

c. Incidents causing risks and basic probability

assignments resulted from the risk identification

step.

3.1.3 Risk Analysis

a. The analysis is performed using the DS Theory,

which is considered a generalized probability

theory in a fixed space. In this theory, the

probability of one potential event is assigned to

reciprocally exclusive sets (Dempster, 1968).

b. The inputs for DS theory are incidents causing

each risk resulting from the initial data analysis

and the initial likelihood for these incidents to

occur.

c. DS theory calculates the combined basic

probability assignment of multiple incidents

causing a specific risk.

d. Three main functions are used in DS theory for

analysis: the basic probability assignment

function (m), the belief function (Bel), and the

plausibility function (Pl) are used in the DS

theory. The basic probability assignment

function defines the probability measure over a

set of sample spaces, mapping each subset to a

value between 0 and 1 (eq 1). It assigns a zero

probability to the empty set (eq 2) and ensures

that the sum of probabilities for all subsets in the

power set equals 1 (eq 3).

𝑚: 𝑃

(

𝑋

)

→ 0,1, (1)

𝑚

(

∅

)

=0, (2)

∑

𝑚(𝐴)

∈()

= 1, (3)

Where P(X) is the power of set X and ∅ the null set.

Figure 1: Risk assessment model for smart city.

ICORES 2025 - 14th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

248

e. The interval [0,1] is defined by two factors:

belief (Bel) and plausibility (Pl). For

example, if set (𝐴

) includes all states under

consideration (risks in this paper), and set

(𝐵

) is considered a subset of these states

(incidents causing the risks), then Bel (𝐴

)

represents the sum of all basic probability

assignments (m) for subsets (𝐵

). Similarly,

plausibility Pl (𝐴

) is the sum of the basic

probability assignments for subsets (𝐵

) that

intersect with the set (𝐴

)

𝐵𝑒𝑙

(

𝐴

)

=𝑚(𝐵

)

|

⊆

(4)

𝑃𝑙

(

𝐴

)

=𝑚(𝐵

)

|

∩

∅

(5)

f. The basic probability assignments denoted as

(m), which are combined based on expert

inputs and risk register documents for risk

incident identification, are analyzed using the

DS combination rule.

g. DS combination rule is a stringent AND

operation on the evidence obtained from

various sources to form a joint belief (Sentz

& Ferson, 2002).

h. The joint belief, represented through a basic

probability assignment (𝑚

), is decided by

summing the product of the basic probability

assignments for all sets (referred to as

incidents in this context), as shown in (eq 6).

According to (eq 7), the combined basic

probability assignment (𝑚

), of the null set

is zero.

i. The variable (K) is the basic probability

assignment in conflict scenarios, occurring

when the intersection between incidents is

null, as indicated in (eq 8). The factor (1-K)

is the normalization factor to mitigate the

influence of conflicting evidence. Table 1

illustrates the combination rule parameters.

j. The risk analysis is applied to a sample risk,

which is data protection and privacy, referred

to as DPR. Data protection and privacy risk

is caused by multiple incidents; for example,

incident B incident C, the basic probability

assignment of incident B is denoted as

𝑚

(

𝐵

)

, and the basic probability

assignment for incident C is denoted as

𝑚

(𝐶)

Table 1: DS combination rule parameters.

The following formula shows the combination rule,

which merges the basic probability assignment of a

subset (B) (representing the risk's first incident in this

research) with the basic probability assignment of a

subset (C) (representing the second incident). In this

context, DPR refers to the set of incidents causing this

specific risk. The DS combination rule emphasizes

the agreement among various incidents, which are

sources of risk while reducing the influence of

conflicting data using a normalization factor.

𝑚

(

𝐷𝑃𝑅

)

=

∑

∩

(

)

()

, when

𝐷𝑅𝑃 ≠ ∅

(6)

𝑚

(

∅

)

=0

(7)

were, K=

∑

𝑚

(

𝐵

)

𝑚

(𝐶)

∩∅

(8)

k. As a result of the risk analysis step, incident

combinations are utilized to calculate the

probability of risk occurrence using Bayesian

theory and to identify interrelations through a

Bayesian Network (BN), as the illustrated

formulas in (Stephenson, 2000). Risk scenarios

are developed during risk analysis based on the

initial data analysis from experts' interviews and

the combinations derived from the DS theory.

The complexity of smart city project and the

multiple stakeholders made the development of

the risk scenarios challenging.

3.1.4 Risk Evaluation

a. The risk evaluation step is completed through

risk scenario identification and evaluation.

b. Risk scenarios are represented using a Bayesian

Network, a graphical probabilistic model. The

Bayesian Network (BN) is a directed acyclic

Notation Description

𝑚

(DPR)

Combined basic probability assignment

of a risk of interest (DPR)

𝑚

(𝐵)

Basic probability assignment of an

incident (B)

𝑚

(𝐶)

Basic probability assignment of incident

(C)

K

Basic probability assignment of a conflict

situations

Modeling for Assessment of Risks in Smart City Mobility Operations

249

graph where all edges have a specific direction,

used to find the joint probability of variables

(Stephenson, 2000).

c. The joint probability from the Bayesian Network

is used to calculate the combined probability for

each scenario. Specifically, the combined basic

probability assignment for a given risk is

considered. For instance, the joint probability

resulting from other risks causing operation risk

(OP) is illustrated as follows:

P (CybR, DPR, OP) = P (OP| DPR).

P(OP). P(DPR

|

C

y

br).

(9)

Where OP is operation phase risk, DPR is data

protection and privacy risk, and CybR is

Cybersecurity risk.

The general equation for the joint probability

function in the Bayesian Network is presented as

follows:

P(X) =

∏

(𝑃(𝑋

|𝑃𝑎𝑟𝑒𝑛𝑡𝑠 (𝑋

))

(10)

d. The resulting joint probability for each risk

scenario is used to create decision-making

criteria by evaluating these scenarios against

their impacts on smart city sustainability using

the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP). As

introduced by Saaty (1987), AHP involves

pairwise comparisons of risks, where preferences

between elements are assessed on a scale from 1

to 9. The consistency index (CI) and consistency

ratio (CR) are calculated based on these ratings.

If the CR is less than or equal to 0.1, the

evaluation matrix is considered acceptable

(Awasthi & Chauhan, 2011).

e. The evaluation vector is then used to assess each

risk scenario using the weighted sum method.

The following section will provide the collected data

and the application of the first two steps of the model,

where risks will be identified in the first step and

analyzed in the second step of the model.

3.2 Data Collection

Data on smart mobility in Qatar are collected through

an operation team focus group. The discussions

focused on the research questions. Comprehensive

conversations with the focus group took place to

identify the interrelations between risks based on their

experience and daily observations. Also, common

incidents causing risks are used to develop the risk

scenarios.

Project documents were examined to find risks

and risk management strategies throughout the

operation phase for smart mobility. The data collected

are summarized in Table 2, where risks are

considered, incidents causing each risk, and the

experts' basic probability assignment for each

incident to occur; the risk register presents three years

of operation. The basic probability assignments are

ranked using a Likert scale where five is considered

very high probability, four is high, three is moderate,

two is low, and one is very low.

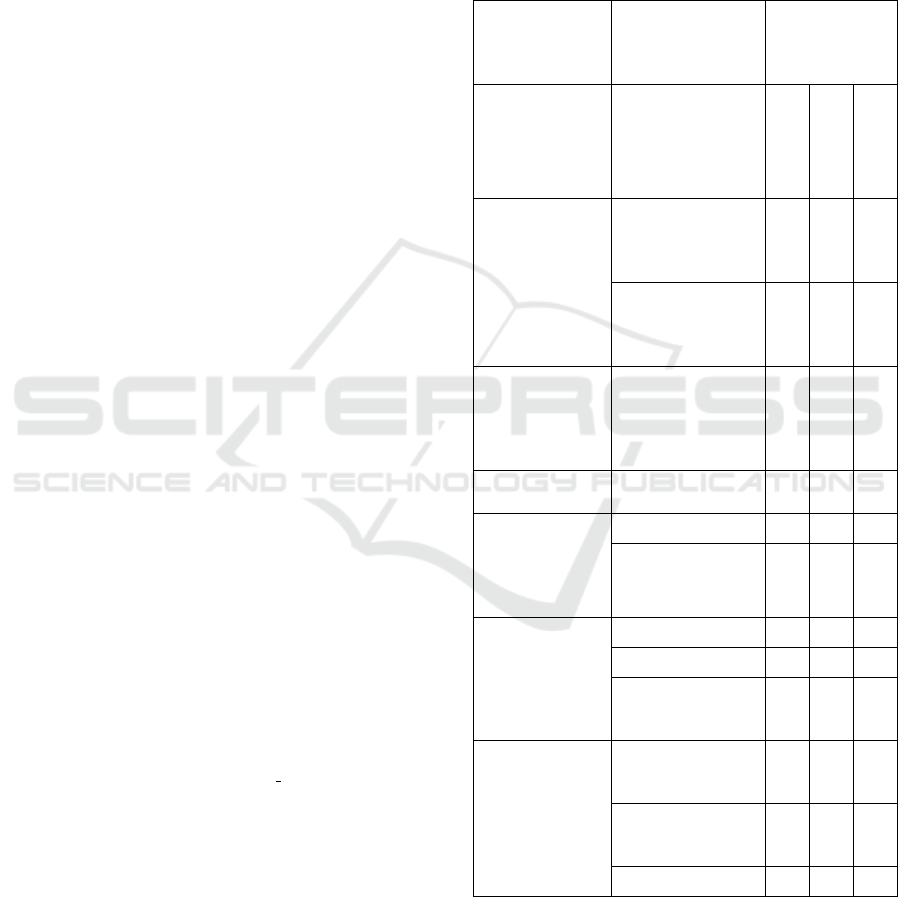

Table 2: Smart transportation application operational risks.

Risk

Incidents causing

risks

Basic

Probability

Assignment

(m)

Year1

Year2

Year 3

Partners

Engagement

Risk

Lack of

communication

between different

Partners

4 3 4

Turnover of some

outsourced

employees from

p

artners

4 3 4

Professionals

and consultants

Risk

Limited

knowledgeable

and trained

experts and

consultants

2 2 3

Continuity of

Operation risk

No clear disaster

recovery plan

4 4 4

Communication

and Network

Infrastructure

risk

Cyberattacks 5 5 5

Lack of

maintenance

model for systems

4 4 3

Data Protection

and Privacy

Risk

Operational error 4 4 3

Cyber attacks 5 5 5

Lack of security

awareness at the

users' level

3 3 2

Cybersecurity

Lack of

maintenance

model for systems

4 4 3

Lack of security

awareness at the

users' level

3 3 2

Cyberattacks 5 5 5

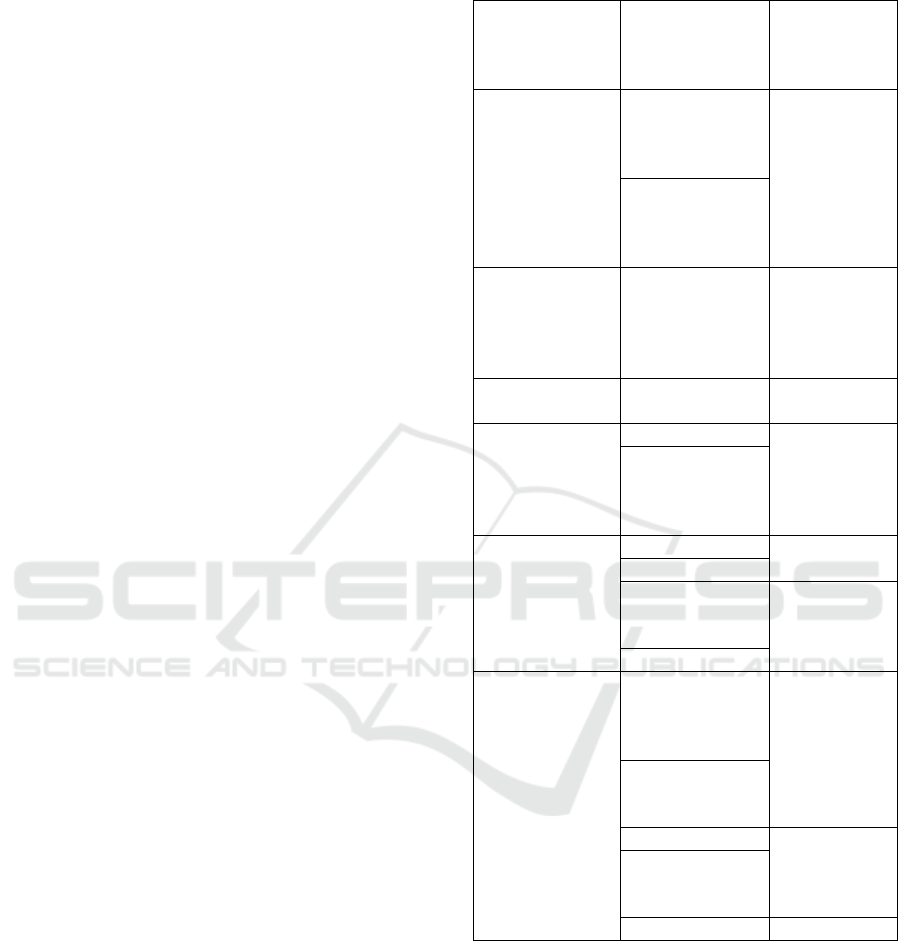

3.3 Application of DS Theory and

Combination Rule

Application of DS theory and combination rule is

ICORES 2025 - 14th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

250

performed to calculate combined basic probability

assignments for the identified risks, which is

presented in Table 3. The combinations of incidents

causing each risk with the highest values are

presented to be considered by the decision-makers.

For each risk, DS theory is applied to incidents as

illustrated in section 3.1, in the risk analysis step.

The collected data presents that partners'

engagement risk resulted from the incidents of lack of

communication between partners and turnover of

some outsourced employees from partners. Applying

DS theory to the data from year 1, year two, and year

three shows that partner engagement risk will occur

due to both incidents occurring concurrently with a

value of 0.444, with the highest combined basic

probability assignment resulting from DS theory and

combination rule application.

For professional and consultant risk, the

combined basic probability assignment of the

incident

limited knowledgeable and trained experts and

consultants for the three years is 0.222.

Continuity of operation risk is caused by no clear

disaster recovery plan. Combining the three years of

data of the basic probability assignment shows that

the combined basic probability for this risk to occur

is a value of 0.222.

Data protection and privacy risk are caused by

three incidents: operation error, lack of security

awareness at the user level, and cyberattacks.

Application of DS theory and combination rule

results that the combined basic probability

assignment has a value of 0.667 for the risk to occur

due to operational error and cyberattacks occurring

simultaneously. The risk has a combined basic

probability assignment of 0.447 to occur if operation

error, lack of security awareness, and user' level

incidents happen at the same time.

Cybersecurity risk results from a lack of

maintenance model for systems, lack of security

awareness at the users' level, and cyberattacks.

Applying the DS theory and combination rule shows

that the combined basic probability assignment for

this risk to occur due to cyberattacks alone is 0.667.

Also, if there is a lack of security awareness at the

users' level and cyberattacks happen concurrently, the

combined basic probability assignment for

cybersecurity risk to occur is 0.667. The incidents of

lack of security awareness at the users' level and lack

of maintenance model for the system, if occurred

simultaneously, will cause cybersecurity risk to occur

with combined basic probability assignment with a

value of 0.447

Table 3: Combined basic probability assignments.

Risk

Combined

incidents

Combined

basic

probability

assignment

Partners

Engagement

Risk

Lack of

communication

between different

Partners

0.444

Turnover of some

outsourced

employees from

partners

Professionals and

consultants Risk

Limited

knowledgeable

and trained

experts and

consultants

0.222

Continuity of

Operation risk

No clear disaster

recovery plan

0.222

Communication

and Network

Infrastructure

risk

Cyberattacks

0.667

Lack of

maintenance

model for

systems

Data Protection

and Privacy Risk

Operational error

0.667

Cyberattacks

Lack of security

awareness at the

users' level

0.447

Operational error

Cybersecurity

Lack of

maintenance

model for

systems

0.447

Lack of security

awareness at the

users' level

Cyber attacks

0.667

Lack of security

awareness at the

users' level

Cyberattacks 0.667

The common risk scenario for operation risk to

occur is due to the occurrence of cybersecurity risk

that will cause data protection and privacy risk,

causing operations discontinuity of interruptions.

P (CybR, DPR, OP) = P (OP| DPR). P(OP).

P(DPR| Cybr)

The joint probability for this scenario is calculated

using (eq10); using the collected data, the value for

the probability of this scenario to transpire is

P (CybR, DPR, OP) = 0.495

Modeling for Assessment of Risks in Smart City Mobility Operations

251

4 DISCUSSIONS

Smart city operation is a complex and

multidisciplinary task where multiple smart systems

must be considered. Since the provided services

within the smart city depend on technological and

non-technological factors, the smart city operation

phase will be vulnerable to multiple risks. This paper

focussed on two research questions. The first one is

related to operation phase risks related to smart

mobility.

The literature shows that during the operation

phase of smart mobility applications, including

technology risks such as cybersecurity and

interoperability, and non-technology risks such as

lack of standards and governance. Smart mobility, as

a major dimension of a smart city, has applications

such as smart transportation systems, which are

studied in this paper.

The technical risks considered in the sample

transportation system are like the risks reviewed in

the literature, yet operation teams need to consider

interoperability risks between various smart mobility

applications.

For non-technology risks, legislation risks,

governance risks, and lack of policies and standards

risks need more attention from operation and

decision-making teams to avoid challenges, such as

service discontinuity, and reputation damage. The

previous paragraph answered the first research

question regarding the main operation phase risks in

smart mobility applications.

The second research question concerns the tools

and models that can be used for assessment. A model

with four main steps and three main tasks (risk

identification, risk analysis, and risk scenarios

evaluation) is proposed. The model uses a focus

group and documentation search (qualitative

approach) for data collection. At the same time, the

analysis phase used DS theory to quantify the

likelihood of risks occurring and to calculate the

combined probability of risk occurrence. The

Bayesian network is used for scenario presentation in

the fourth step, and scenario probabilities are

calculated using Bayesian theory. The presented

scenario probability shows that operation risk will

occur due to technology-related risks, especially

when cybersecurity risk occurs since it will lead to a

cascading effect on other risks.

The model is tested on smart transportation

applications in the operation phase in Qatar. In Qatar,

the operation team considers six main risks:

cybersecurity, data protection and privacy,

communication and network infrastructure, partner

engagement, professional and consultant, and

continuity of operations. The data provided the

incidents leading to these risks and the experts' basic

probability assignments for the incident to arise.

Technology-related risks, namely cybersecurity, data

privacy and protection, and communication and

network infrastructure risks, share similar incidents.

Thus, they are interrelated. The combined incidents

with cyberattack incidents have a high basic

probability assignment. Accordingly, serious

protective measures need to be taken to avoid or

minimize the consequences on smart transportation

systems in case such incidents occur.

The paper shows that applying DS theory and the

combination rule provides a quantitative value for

combined basic probability assignments for incidents.

Accordingly, decision-makers can take the proper

measures to manage these risks. High probability

risks from specific incidents will be clear, and

mitigation plans can be developed to avoid or

minimize the consequences of the risks.

For instance, the combined basic probability

assignments for the incidents, cyber-attacks, and lack

of security awareness at the users' level is 0.667,

which is considered high probability(Acebes et al.,

2024) and, in comparison to the other incidents, and.

Thus, in the case of an application, management

needs to take measures to raise cyberattack security

awareness.

Also, looking at partners' engagement risk, the

probability of the two incidents causing this risk to

occur in the same period is obtained as 0.444.

Therefore, management must ensure proper

communication between different partners and

minimize the turnover of outsourced employees,

specifically from partners.

Identifying individual scenarios is challenging, as

each smart city scenarios could be different due to

unique design of applications systems and represent

complexity through a number of interconnections

between systems and stakeholders (Damasiotis,

2022).

Based on the outcome, it can be mentioned that

data gathering and analysis with DS theory can help

decision-makers understand the risk situation and

prepare the right measures to mitigate risk impact.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The paper reviews various risk factors and assessment

models that can be applied to smart mobility

applications. A model is proposed to address risks in

smart mobility. The model is tested on a smart

ICORES 2025 - 14th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

252

transportation application in Qatar and found that the

assessment with the proposed model can help make

risk management decisions.

Future research can investigate the interrelations

between smart mobility risks, apply the Bayesian

Network and theory, and produce a decision-making

criterion for this significant smart city dimension.

Another aspect of future research is investigating

the transferred risks from the design or

implementation phases of the smart city application

lifecycle. Finding a way to consider them in

probability calculations will provide robust results

when the decision-making criteria are built.

REFERENCES

Acebes, F., González-Varona, J. M., López-Paredes, A., &

Pajares, J. (2024). Beyond probability-impact matrices

in project risk management: A quantitative

methodology for risk prioritisation. Humanities and

Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1–13.

https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03180-5

Alanazi, F., & Alenezi, M. (2024). Interoperability for

intelligent traffic management systems in smart cities.

International Journal of Electrical and Computer

Engineering, 14(2), 1864–1874. https://doi.org/10.

11591/ijece.v14i2.pp1864-1874

Alawad, H., An, M., & Kaewunruen, S. (2020). Utilizing an

adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) for

overcrowding level risk assessment in railway stations.

Applied Sciences (Switzerland), 10(15). https://doi.

org/10.3390/app10155156

Ande, R., Adebisi, B., Hammoudeh, M., & Saleem, J.

(2020). Internet of Things: Evolution and technologies

from a security perspective. Sustainable Cities and

Society, 54(February 2019), 101728. https://doi.org/10.

1016/j.scs.2019.101728

Appio, F. P., Lima, M., & Paroutis, S. (2019).

Understanding Smart Cities: Innovation ecosystems,

technological advancements, and societal challenges.

Technological Forecasting and Social Change,

142(December 2018), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

techfore.2018.12.018

Awasthi, A., & Chauhan, S. S. (2011). Using AHP and

Dempster-Shafer theory for evaluating sustainable

transport solutions. Environmental Modelling and

Software, 26(6), 787–796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

envsoft.2010.11.010

Damasiotis, V. (2022). Modeling Project Management

Complexity in Smart Cities’ Projects. In P. Fitsilis

(Ed.), Building on Smart Cities Skills and

Competences: Human factors affecting smart cities

development (pp. 169–183). Springer International

Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-97818-

1_10

Dempster, A. P. (1968). A Generalization of Bayesian

Inference. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society:

Series B (Methodological), 30(2), 205–232.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1968.tb00722.x

Deveci, M., Pekaslan, D., & Canıtez, F. (2020). The

assessment of smart city projects using zSlice type-2

fuzzy sets based Interval Agreement Method.

Sustainable Cities and Society, 53(August 2019).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101889

Domingos, P., Rita, A., Terra, T., & Ignácio, S. R. (2008).

FMEA as a Tool for Managing Risks in ICT Projects ,

based on the PMBOK. Asian Journal of Business and

Management Sciences, 3(12), 1–24.

Fernandez-Anez, V., Velazquez, G., Perez-Prada, F., &

Monzón, A. (2018). Smart City Projects Assessment

Matrix: Connecting Challenges and Actions in the

Mediterranean Region. Journal of Urban Technology,

0(0), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10630732.

2018.1498706

Hasija, S., Shen, Z. J. M., & Teo, C. P. (2020). Smart city

operations: Modeling challenges and opportunities.

Manufacturing and Service Operations Management,

22(1), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1287/msom.

2019.0823

Ismagilova, E., Hughes, L., Dwivedi, Y. K., & Raman, K.

R. (2019). Smart cities: Advances in research—An

information systems perspective. International Journal

of Information Management, 47(December 2018), 88–

100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.01.004

Lacinák, M. (2021). Resilience of the Smart Transport

System - Risks and Aims. Transportation Research

Procedia, 55, 1635–1640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

trpro.2021.07.153

Lee, I. (2020). Internet of Things (IoT) Cybersecurity:

Literature Review and IoT Cyber Risk Management.

Future Internet, 12(9), 157. https://doi.org/10.

3390/fi12090157

Oladimeji, D., Gupta, K., Kose, N. A., Gundogan, K., Ge,

L., & Liang, F. (2023). Smart Transportation: An

Overview of Technologies and Applications. Sensors,

23(8), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23083880

Paiva, S., Ahad, M. A., Tripathi, G., Feroz, N., & Casalino,

G. (2021). Enabling technologies for urban smart

mobility: Recent trends, opportunities and challenges.

Sensors, 21(6), 1–45. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21062143

Patrão, C., Moura, P., & Almeida, A. T. de. (2020). Review

of Smart City Assessment Tools. Smart Cities, 3(4),

1117–1132. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities3040055

Porru, S., Misso, F. E., Pani, F. E., & Repetto, C. (2020).

Smart mobility and public transport: Opportunities and

challenges in rural and urban areas. Journal of Traffic

and Transportation Engineering (English Edition),

7(1), 88–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtte.2019.10.002

Sentz, K., & Ferson, S. (2002). Combination of Evidence in

Dempster- Shafer Theory. Contract, April, 96.

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.

1.1.122.7929&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Sharif (RS), R. Al, & Pokharel (SP), P. S. (2021). Smart

City Dimensions and Associated Risks: Review of

literature. Sustainable Cities and Society, June, 103542.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.103542

Modeling for Assessment of Risks in Smart City Mobility Operations

253

Sharif, R. Al, & Pokharel, S. (2021a). Risk analysis with

the dempster–shafer theory for smart city planning: The

case of qatar. Electronics (Switzerland), 10(24).

https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10243080

Sharif, R. Al, & Pokharel, S. (2021b). Smart City

Perspectives in the Context of Qatar. Sustainable Smart

Cities and Territories International Conference, 103–

113.

Sharma, A., & Singh, U. K. (2022). Modelling of smart risk

assessment approach for cloud computing environment

using AI & supervised machine learning algorithms.

Global Transitions Proceedings, 3(1), 243–250.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gltp.2022.03.030

Shayan, S., Kim, K. P., Ma, T., & Nguyen, T. H. D. (2020).

The first two decades of smart city research from a risk

perspective. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(21), 1–20.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219280

Silva, B. N., Khan, M., & Han, K. (2018). Towards

sustainable smart cities: A review of trends,

architectures, components, and open challenges in

smart cities. Sustainable Cities and Society, 38(August

2017), 697–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.

2018.01.053

Singh, P., & Helfert, M. (2019). Smart cities and associated

risks: Technical v/s non-technical perspective. CHIRA

2019 - Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference

on Computer-Human Interaction Research and

Applications, May, 221–228. https://doi.org/10.

5220/0008494402210228

Stephenson, T. (2000). Main Bayesian Network Auxiliary

Article. Idiap Research Report, 31.

http://ftp.idiap.ch/pub/reports/2000/rr00-03.pdf

Suthanthira Vanitha, N., Radhika, K., Maheshwari, M.,

Suresh, P., & Meenakshi, T. (2021). IoT‐Based

Intelligent Transportation System for Safety. Cloud and

IoT‐Based Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks, 47–65.

https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119761846.ch3

Tao, W. (2013). Interdisciplinary urban GIS for smart

cities: Advancements and opportunities. Geo-Spatial

Information Science, 16(1), 25–34. https://doi.org/10.

1080/10095020.2013.774108

Ullah, F., Qayyum, S., Thaheem, M. J., Al-Turjman, F., &

Sepasgozar, S. M. E. (2021). Risk management in

sustainable smart cities governance: A TOE

framework. Technological Forecasting and Social

Change, 167(November 2020), 120743. https://doi.

org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120743

Ullah, I. (2018). applied sciences Analytical Modeling for

Underground Risk Assessment in Smart Cities.

https://doi.org/10.3390/app8060921

Ye, T., Zhuang, Y., & Qiao, G. (2023). SCKPISec: A KPI-

Guided Model-Based Approach to Realize Security by

Design for Smart City Systems. Sustainability

(Switzerland),

15(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/

su15031884

Zheng, C., Yuan, J., Zhu, L., Zhang, Y., & Shao, Q. (2020).

From digital to sustainable: A scientometric review of

smart city literature between 1990 and 2019. Journal of

Cleaner Production, 258, 120689. https://doi.org/10.

1016/j.jclepro.2020.120689.

ICORES 2025 - 14th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

254