Predicting Postpartum Depression in Maternal Health Using Machine

Learning

Maria Alejandra Terreros-Lozano

1

, Diana Lopez-Soto

2

, Samuel Nucamendi-Guillén

1

and María Alejandra López-Ceballos

1

1

Universidad Panamericana, Facultad de Ingeniería, Álvaro del Portillo 49, Zapopan, Jal, 45010, Mexico

2

Department of Industrial and Manufacturing Engineering, North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND, 58108, U.S.A.

Keywords: Postpartum Depression, Machine Learning, Maternal Health, Predictive Modelling, Random Forest, PRAMs

Data.

Abstract: Postpartum depression (PPD) is a severe mental health condition affecting mothers after childbirth,

characterized by prolonged sadness, anxiety, and fatigue. Unlike the transient "baby blues," PPD's symptoms

can last months, impacting a mother's ability to care for herself and her baby. In the U.S., PPD affects about

1 in 7 women, with a significant rise in prevalence from 13.8% to 19.8% in recent years. This condition leads

to adverse effects on maternal and infant health. Early diagnosis and treatment of PPD can help prevent long-

term depression and minimize the emotional and financial burden associated with the condition. This research

aims to evaluate machine learning models to predict PPD risk. Critical factors were identified, and an accuracy

of 96.57% and a precision of 99.88% were obtained. This predictive model enables early, personalized

interventions, aiming to improve maternal health outcomes and reduce the societal burden of PPD.

1 INTRODUCTION

Maternal health encompasses the well-being of

women throughout pregnancy, childbirth, and the

postnatal period. Health care should strive to ensure

that every phase is a positive experience, ensuring

that both women and their babies achieve their

highest potential for health and wellness.

The World Health Organization (WHO) reports

that about 140 million births occur annually, with the

percentage attended by skilled health personnel rising

from 58% in 1990 to 81% in 2019. This increase is

primarily attributed to more births in health facilities

with trained midwives and doctors (Maternal health

n.d.). From 2000 to 2020, the rise in the specialization

of maternal health care contributed to a decrease of

34% (from 339 deaths to 223 deaths per 100,000) in

deaths due to complications during pregnancy,

childbirth, and the postnatal period. However, with an

average annual reduction of just under 2.1%, the rate

of progress remains insufficient (Maternal mortality

rates and statistics n.d.). Furthermore, the U.S. has a

mortality rate far outstrips that of the other

industrialized nations, with a rate of 22.3 deaths per

100,000 live births (Hoyert 2024).

Various complications during pregnancy can lead

to the death of the mother. Some common

complications of pregnancy are high blood pressure,

gestational diabetes, infections, miscarriage, and

others. Moreover, women may also suffer

complications after giving birth, such as postpartum

depression (PPD). PPD is a medical condition related

to strong feelings of sadness, anxiety, and tiredness.

It is estimated that in the U.S., between 13.8% and

19.8% of women experience some type of PPD

(Bermúdez Serrano 2024), and of those, 50% are not

diagnosed by a health professional (Postpartum

Depression Statistics | Research and Data On PPD

(2024) 2024). PPD is a factor in 20% of all maternal

deaths (Hagatulah et al. 2024). Therefore, it is crucial

to address this issue to improve maternal health

outcomes. The goal of this research is to identify the

factors that increase women’s risk of developing

postpartum depression.

2 PROBLEM DESCRIPTION

Postpartum depression is often confused with Baby

Blues, but the main difference is the intensity and

duration of the symptoms. During the first two weeks

Terreros-Lozano, M. A., Lopez-Soto, D., Nucamendi-Guillén, S. and López-Ceballos, M. A.

Predicting Postpartum Depression in Maternal Health Using Machine Learning.

DOI: 10.5220/0013155700003893

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems (ICORES 2025), pages 255-263

ISBN: 978-989-758-732-0; ISSN: 2184-4372

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

255

after childbirth, mothers experience hormonal

changes that can cause anxiety, crying, and

restlessness, and 85% of mothers experience this,

which is expected given the abrupt change in life

having to take care of a newborn; these first two

weeks are known as the baby blues (Baby Blues and

Postpartum Depression 2024). Postpartum depression

usually appears two to eight weeks after giving birth

but can happen up to years. The symptoms to be

aware of include feeling overwhelmed, constant

crying, difficulty bonding with your baby, and

doubting your ability to care for yourself and your

baby (What is postpartum depression? n.d.).

PPD can be experienced in different ways by

different mothers. One of them is postpartum anxiety,

and the symptoms to identify it include far more

anxious behaviors than primarily depressed behavior,

like persistent fears and worries, high tension and

stress, and inability to relax (Postpartum Depression

Types - Pyschosis, OCD, PTSD, Anxiety and Panic

2023). There’s also postpartum obsessive-

compulsive disorder (OCD), which affects 3% to 5%

of new mothers. Symptoms of postpartum OCD

involve intrusive and persistent thoughts, often

centered around harming or even killing the baby

(Postpartum Depression Types - Pyschosis, OCD,

PTSD, Anxiety and Panic 2023). Postpartum panic

disorder occurs in up to 10% of postpartum women;

they experience intense anxiety and recurrent panic

attacks (Postpartum Depression Types - Pyschosis,

OCD, PTSD, Anxiety and Panic 2023). Postpartum

post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) takes place in

a mother's life when they experience a traumatic

experience before, during, or shortly after giving

birth; it results in a chronic mental health issue that

creates anxiety or panic-like symptoms. Postpartum

PTSD and PPD can co-occur, creating a complex case

and treatment challenge (Postpartum Depression

Types - Pyschosis, OCD, PTSD, Anxiety and Panic

2023).

Bermudez Serrano (Bermúdez Serrano 2024)

explains that if mothers are not monitored and given

the necessary care, they may develop postpartum

psychosis, which occurs in 1 in 1000 women. The

likelihood of experiencing such episodes is higher in

women who had mental health issues before

pregnancy. Those affected by postpartum psychosis

may experience hallucinations and suicidal or

infanticidal thoughts, making the early detection of

symptoms crucial for prompt treatment.

Although PPD is one of the most important causes

of maternal mortality, it is not the only repercussion.

Untreated PPD appears to have adverse effects on

both infants and mothers. Nonsystematic reviews

suggest that children of untreated depressed mothers,

compared to those of mothers without PPD, face risks

such as poor cognitive development, behavioral

inhibition, emotional issues, violent behavior,

externalizing disorders, and psychiatric and medical

problems during adolescence (Slomian et al. 2019).

Other reviews, both nonsystematic and systematic,

have identified specific maternal risks associated with

untreated PPD, including weight issues, alcohol and

drug use, social relationship difficulties,

breastfeeding challenges, and persistent depression,

compared to women who received treatment

(Slomian et al. 2019).

According to recent studies in the American

Journal of Public Health, the cost of untreated

perinatal mood and anxiety disorder (PMADs) for

2017 is a total of USD 14.2 billion (Health 2020).

This study is intended to support the early diagnosis

of PPD, and therefore, decision-makers can act

proactively and reduce risks to mother and child, as

well as costs.

3 RELATED RESEARCH

Machine learning (ML) techniques have been

effectively employed to forecast the persistence,

chronicity, severity of major depressive disorder, and

response to treatment (Kessler et al. 2016). Various

studies on depression prediction have primarily

utilized supervised ML algorithms: support vector

machines (SVM) and random forests (Jin 2015)

(Natarajan et al. 2017). There was a study that used a

multi-part survey consisting of demographic

questions, known PPD risk factors, and potential

symptoms of PPD. They implemented regression

trees and gradient-boosting methods to answer

whether PPD can be predicted from non-clinical data

and whether ML is viable for PPD prediction. With

the help of ML techniques, they ensure that PPD

occurs in mothers who have a terrible relationship

with their partners or do not receive assistance from

them. They aimed to develop a self-diagnosis tool and

treatment plan for new mothers (Natarajan et al.

2017).

Amit et al. (Amit et al. 2021) also worked on

predicting PPD risk using machine learning applied

to electronic health records (EHR). A gradient tree-

boosting algorithm was used to analyze data from

266,544 women. Their model obtained an accuracy of

0.805, but when combined with the Edinburgh

Postanal Depression Scale (EPDS), it significantly

improved to 0.844.

ICORES 2025 - 14th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

256

There’s also a related study by Bjertrup et al.

(Bjertrup, Væver, and Miskowiak 2023), where an

online neurocognitive risk screening tool was

developed to predict PPD. In their method, they used

emotional reactivity and evaluation of infant distress,

analyzed through statistical models, to predict PPD

risk in pregnant women. The results obtained showed

that negative reactivity to infant distress was a strong

predictor of PPD onset. The study concluded that

neurocognitive bias during pregnancy could serve as

a biomarker for PPD.

Other research has implemented nine different

supervised ML algorithms, including random forest

(RF), stochastic gradient boosting, support vector

machines (SVM), recursive partitioning and

regression trees, naïve Bayes, k-nearest neighbor

(kNN), logistic regression, and neural network, to

evaluate models with only demographic and lifestyle

variables to predict PPD (Shin et al. 2020). They

found that women with PPD were more likely to have

less education and had depression before pregnancy.

Both investigations based their analysis on

demographic data. In this research, we included

health pre-pregnancy, health during pregnancy,

prenatal care, factors giving birth, health postpartum,

use of drugs or smoking before and during pregnancy,

if abused, and information on the infant data.

4 METHODOLOGY

The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System

(PRAMS) data set from 2016–2021 from the Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was

analyzed for this study. PRAMS gathers state-

specific, population-based information on maternal

characteristics and experiences in the United States

before, during, and after pregnancy. A sample of

women who recently gave birth to live infants was

chosen from state birth certificate registries, and these

women were invited to participate in the PRAMS

survey (CDC 2024). The PRAMS questionnaire

consists of three sections: a core set of questions used

by all sites, a collection of standardized optional

questions that sites can choose from, and site-specific

questions typically utilized only by the site that

created them (CDC 2024). The PRAMS data from

2016 to 2021 included a total of 221,382 participants.

After cleaning the database (eliminating records with

inconsistencies and missing information), 8,103

records containing complete patient information were

selected.

There were over 500 variables. First, the data was

cleaned by classifying the information into nine

sections: demographics, pre-pregnancy, health during

pregnancy, prenatal care, factors giving birth, health

postpartum, use of drugs or smoking before and

during pregnancy, if abused, and information about

the infant. Then, observations with missing

information were discarded for further analysis to

find the variables that had the strongest relationship

with whether the mother had PPD or not. After doing

this, and with the help of contingency tables, a result

of 42 variables was achieved.

To facilitate practitioners' implementation of this

model, a second selection of variables was developed

using ‘feature importances’, based on the Decision

Tree Classifier algorithm (Matsumura et al. 2025).

This selection aimed to compare the accuracy

achieved after reducing the number of variables. This

evaluates whether the reduction in variables is

justified by an acceptable loss of accuracy in the

model. Fifteen variables were selected, which

resulted in the following.

Both sets of selected variables were assessed

using six classification algorithms: k-Nearest

Neighbor (kNN), classification tree analysis (CTA),

Random Forest (RF), Artificial Neural Network

(ANN), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGboost),

Extremely Randomized Trees Classifier (Extra Trees

Classifier). Four different sample sizes were used for

each classification algorithm, and ten different

samples were run for each size, thus obtaining the

averages presented in the following section. To

develop and implement these algorithms, reference

the codes published on the website: https://scikit-

learn.org/stable/.

As a result, our database shows that there are

1,134 records with PPD, which corresponds to 14%

of the database, and 6,969 records without it. These

records are independent of each other. There is no

correlation between the results.

All experiments were performed using a PC Intel

Core i7 @2.40 GHz with 16 GB of RAM Memory

under Windows 11 OS.

5 RESULTS

In order to determine whether the number and types

of variables selected affect the performance of the

selected methods, we compared both scenarios: the

one taking 42 variables, which include demographics,

health pre-pregnancy, health during pregnancy,

prenatal care, factors giving birth, health postpartum,

use of drugs or smoking before and during pregnancy,

if abused, and information of the infant data, and the

other considering only the 15 variables selected.

Predicting Postpartum Depression in Maternal Health Using Machine Learning

257

ICORES 2025 - 14th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

258

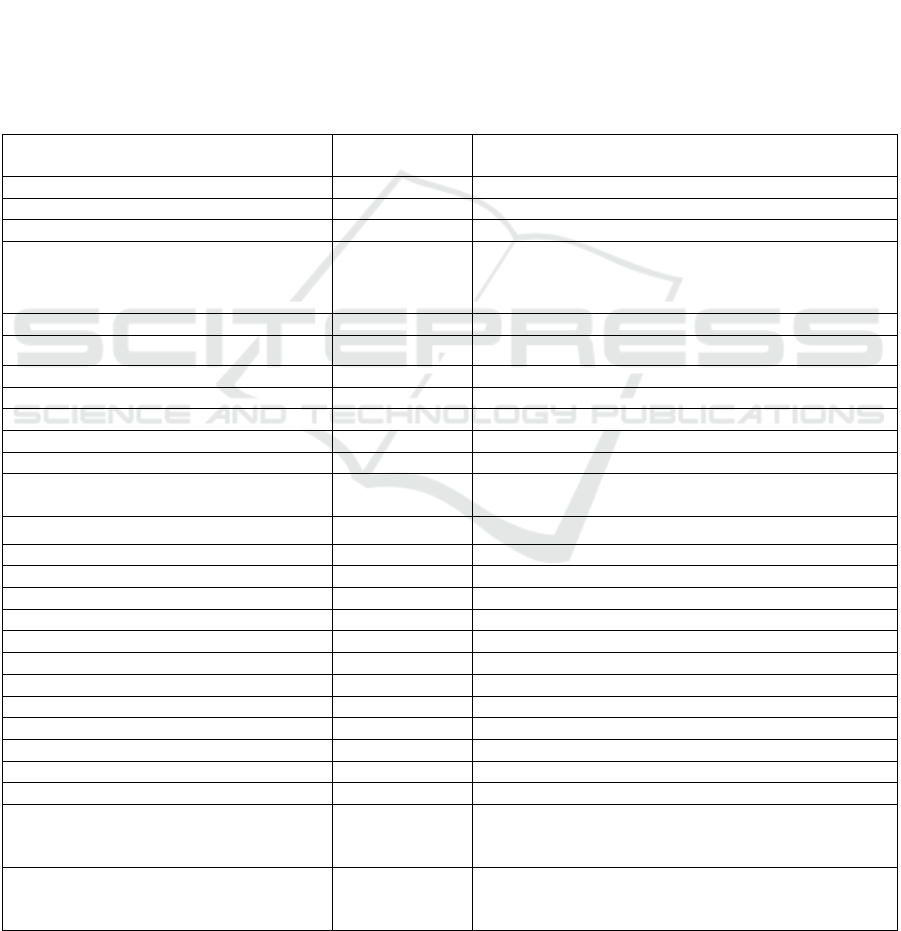

Table 1: Description of the variables selected.

Variable

Scale

Measurement

Levels of measurement

Mothers age Categorical

1= 17-20 YEARS OLD, 2= 21-25 YEARS OLD, 3= 26-30 YEARS

OLD, 4= 31-35 YEARS OLD, 5= 36-40 YEARS OLD, 6= 41-45

YEARS OLD

Mothers’ education level Categorical

0= UNKNOWN, 1=<= 8TH GRADE, 2=9-12 GRADE,NO

DIPLOMA, 3=HIGH SCHOOL GRAD/GED, 4=SOME

COLLEGE, NO DEG/ASSOCIATE DEG,

5=BACHELORS/MASTERS/DOCTORATE/PROF

Mother income Categorical

1 = LOWER CLASS (=<$28,007), 2=LOWER MIDDLE CLASS

($28,008 to $55,000), 3= MIDDLE CLASS ($55,001 to $89,744)

Pregnant intention Categorical

1=LATER, 2=SOONER, 3=THEN

4=DID NOT WANT THEN OR ANY TIME, 5=WAS NOT SURE

No. of previous live births Categorical 0=0, 1=1, 2=2, 3=3-5, 4=6+

No. of previous pregnancy

outcomes

Discrete

quantitative

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

Vitamin intake per week

during pregnancy

Categorical

1=DIDNT TAKE VITAMIN, 2=1-3 TIMES/WEEK, 3=4-6

TIMES/WEEK, 4=EVERY DAY/WEEK

Depression during pregnancy Binary YES = 1, NO = 0

Mom BMI (Body Mass Index) Categorical

1=UNDERWT ( < 18.5), 2=NORMAL (18.5-24.9), 3=OVERWT

(25.0-29.9), 4=OBESE (30.0 + )

Kotelchuck index Categorical

1=INADEQUATE, 2=INTERMEDIATE, 3=ADEQUATE,

4=ADEQUATE PLUS

Attendant at birth Categorical

1=PHYSICIAN (MD), 2=OSTEOPATH (DO), 3=CERT. NURSE

MIDWIFE/CM, 4=OTHER MIDWIFE, 5=OTHER,

6=UNKNOWN

No. of weeks breastfeeding. Categorical

1= 1-5 WEEKS, 2= 6-11 WEEKS, 3= 12-17 WEEKS, 4= 18-23

WEEKS, 5= 24-29 WEEKS, 6= 30-35 WEEKS, 7= 36-40 WEEKS,

8= <1 WEEKS, 9= Didn’t breastfeed

No interest in the baby since

birth

Categorical

1=ALWAYS, 2=OFTEN/ALMOST ALWAYS, 3=SOMETIMES,

4=RARELY, 5=NEVER

Infant age Categorical

0= 0-10 WEEKS, 1= 11-15 WEEKS, 2= 16-20 WEEKS, 3= 21-25

WEEKS, 4= 26-30 WEEKS, 5= 31-35 WEEKS, 6= 35-40 WEEKS

Using birth control

postpartum

Binary YES = 1, NO = 0

Postpartum Depression

Indicator (output variable)

Bernoulli

distribution

YES = 1, NO = 0

Predicting Postpartum Depression in Maternal Health Using Machine Learning

259

Table 2: Obtained results from scenario 1 (42 variables).

Accuracy Precision

Sample Size

Method

10% 15% 20% 30% 10% 15% 20% 30%

kNN 0.8665 0.8469 0.8661 0.8655 0.6772 0.6292 0.5712 0.6061

CTA 0.9411 0.9423 0.9379 0.9399 0.8008 0.7958 0.7921 0.8039

ANN 0.9482 0.9461 0.9481 0.9490 0.8625 0.8517 0.8742 0.8526

XGboost 0.9587 0.9569 0.9558 0.9553 0.9323 0.9490 0.9232 0.9323

RF 0.9657 0.9647 0.9620 0.9616 0.9989 0.9970 0.9970 0.9972

Extra Tree Classifier 0.9639 0.9600 0.9587 0.9597 0.9847 0.9787 0.9821 0.9766

Table 3: Obtained results from scenario 2 (15 variables).

Accuracy Precision

Sample size

Method

10% 15% 20% 30% 10% 15% 20% 30%

kNN 0.8991 0.8949 0.8916 0.8864 0.7543 0.7949 0.7854 0.8075

CTA 0.9429 0.9413 0.9407 0.9440 0.8144 0.7920 0.8055 0.8235

ANN 0.9610 0.9575 0.9560 0.9575 0.9502 0.9346 0.9400 0.9328

XGboost 0.9543 0.9540 0.9582 0.9538 0.9108 0.9097 0.9244 0.9085

RF 0.9629 0.9595 0.9591 0.9601 0.9917 0.9895 0.9931 0.9949

Extra Tree Classifier 0.9571 0.9613 0.9603 0.9623 0.9830 0.9732 0.9831 0.9713

6 RESULTS

In order to determine whether the number and types

of variables selected affect the performance of the

selected methods, we compared both scenarios: the

one taking 42 variables, which include demographics,

health pre-pregnancy, health during pregnancy,

prenatal care, factors giving birth, health postpartum,

use of drugs or smoking before and during pregnancy,

if abused, and information of the infant data, and the

other considering only the 15 variables selected.

We reported the test dataset used to measure the

performance of each method mentioned before. We

considered the accuracy and precision metrics to

evaluate the performance of the selected approaches.

According to Evidently AI Team (Accuracy vs.

precision vs. recall in machine learning n.d.),

accuracy indicates the frequency with which a

classification machine learning model is generally

correct. Precision reflects the rate at which a machine

learning model accurately predicts the target class.

According to the results shown in Table 2, the

highest accuracy was found using Random Forest,

whereas the lowest accuracy was obtained using the

k-Nearest Neighbor with 42 variables (0.9657 and

0.8469, respectively). As for precision, we again got

the highest score using Random Forest and the lowest

using k-Nearest Neighbor with 42 variables (0.9989

and 0.5712, respectively).

On the other hand, we obtained (again) the best

accuracy and precision with random forest (0.9629

and 0.9949, respectively), as seen in Table 3. The

percentages shown in the tables represent the sample

size used in the algorithm after training. These

samples were run ten times to obtain the averages

shown in the table. Both the highest accuracy and

precision were found when a 10% sample size was

used, which indicates that the more training given to

the algorithm, the better the results. It is important to

note that the difference between the best accuracy

obtained from the model with 42 variables and that

from the model with 15 variables is less than 0.3%.

This means we could safely apply the model with 15

variables, which will require less time from

practitioners for follow-up and will not result in any

significant loss of accuracy in predictions.

Based on the chi-squared test of the contingency

tables (including 95% confidence intervals), we

obtained the results of the tendencies of each variable.

Younger mothers, particularly those aged between 18

and 25, are more likely to experience PPD (p-value =

ICORES 2025 - 14th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

260

0.0001). Although the likelihood of depression

decreases as maternal age increases, cases continue to

be observed in mothers up to 45 years of age (p-value:

0.0001).

Educational attainment also plays a crucial role.

Mothers with lower education levels (such as those

with 8th grade or less and 9th-12th grade without a

diploma) are more likely to experience PPD (p-value

= 0.0001). In contrast, higher levels of education are

associated with a lower likelihood of depression (p-

value = 0.0001).

The level of income that each mother has also

represents an association with presenting PPD.

Mothers with lower incomes are more likely to

present PPD (p-value = 0.0001), and mothers with

higher incomes may show it but at a lower percentage

(p-value = 0.0001).

Another significant factor is pregnancy intention.

Mothers who did not want the pregnancy or were

uncertain about it exhibited the highest rates of PPD

(p-value = 0.0001). On the other hand, those who

wished for the pregnancy, whether sooner or at the

time, report lower rates of depression (p-value =

0.0001).

First-time mothers are at a higher risk of PPD,

possibly due to the challenges and adjustments

associated with first-time parenthood (p-value =

0.0333). On the contrary, mothers with more previous

live births (mainly two or more) showed a

significantly lower risk of PPD (p-value = 0.0317).

It seems that mothers with cero previous

pregnancy outcomes are more likely to develop PPD

(p-value = 0.0374), and mothers with one or more

outcomes seem to experience less PPD (p-value =

0.0221). Some outcomes could be spontaneous or

induced losses or ectopic pregnancies. However,

since the groups with more terminations are smaller,

further statistical analysis might be necessary to

confirm these trends.

Mothers who did not take vitamins during

pregnancy are more likely to experience PPD

compared to those who did (p-value = 0.0082).

Regular vitamin intake, particularly daily, is

associated with a lower likelihood of depression,

indicating that prenatal care and nutrition may

contribute positively to postpartum mental health

outcomes (p-value = 0.0085).

For depression during pregnancy, it was presented

that 34.94% of mothers who experience it also report

PPD (p-value = 0.0001), compared to only 8% among

those who did not experience prenatal depression (p-

value = 0.0001). This substantial difference

underlines the importance of addressing mental

health issues during pregnancy to reduce the

likelihood of PPD.

In terms of maternal Body Mass Index (BMI),

underweight mothers (BMI < 18.5) are at the highest

risk of PPD, followed by obese mothers (BMI > 30)

(p-value = 0.0029). While overweight mothers (BMI

25 - 29.9) also show an elevated risk, it is lower than

that of underweight and obese mothers. These

findings suggest that extremes in maternal BMI—

whether too low or too high—can contribute to

postpartum mental health challenges.

The Kotelchuck Index, also known as the

Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization (APNCU)

index, measures the adequacy of prenatal care and is

classified into four categories. Inadequate, which is

associated with the highest risk of PPD (16.38%).

Intermediate and adequate, which presented lower

risks of PPD, which suggests that timely and

sufficient prenatal care helps (p-value = 0.0006); the

final category is adequate plus, it presented a

relatively high rate of PPD, indicating that additional

visits may not always equate to better mental health

outcomes (p-value = 0.0006).

The type of healthcare provider attending the

delivery also affects the likelihood of PPD. Mothers

attended by other midwives have the lowest risk of

PPD (3.70%), followed by certified nurse midwives

(10.74%). In contrast, mothers attended by physicians

and osteopaths exhibit the highest likelihood of PPD,

around 14% (p-value = 0.0219).

The amount of time a mother is able to breastfeed

her baby also has an impact on her mental health, with

women who did not breastfeed or breastfeed for a

short time (1-11 weeks) having the highest rates of

PPD (p-value = 0.0001), with more than 20%

experiencing it. Breastfeeding for 12-23 weeks

appears to be associated with the lowest risk of PPD,

with rates between 10-11% (p-value = 0.0001).

Mothers who consistently showed no interest

since birth are at the highest risk for PPD; the fact that

100% of these women were diagnosed with PPD

suggests that the lack of interest is a strong indicator

of postpartum mental health issues (p-value =

0.0001). Even though the mothers who only

experience that lack of interest sometimes have a

lower risk, there is still the presence of PPD.

Regarding the infant’s age, the mothers who

presented the highest rates of PPD were those with

babies aged less than or equal to 10 weeks (p-value =

0.0002); after the risk decreases, the lowest risk seen

in the 26-30 weeks range (p-value = 0.0002). This

suggests that the early postpartum period is the most

critical time for monitoring and addressing PPD.

Predicting Postpartum Depression in Maternal Health Using Machine Learning

261

Finally, the use of birth control postpartum is

associated with a lower likelihood of PPD. Mothers

not using birth control postpartum are more likely to

experience depression, with 16.27% reporting PPD

(p-value = 0.0009). In contrast, those who use birth

control have a lower rate of depression, with only

13.25% affected (p-value = 0.0007).

7 CONCLUSIONS

PPD is an issue that should have more attention in the

U.S. Now that we know the effects that it has on a

mother and child's life, this is why this research has

the goal to help predict this health issue so decision-

makers can make more informed decisions and be

prepared.

This research has demonstrated that the use of

machine learning techniques can be highly effective

in predicting the risk of postpartum depression (PPD)

in new mothers. Through the analysis of an extensive

and diverse dataset provided by PRAMS, significant

variables influencing the likelihood of developing

PPD were identified, including demographic, health-

related, and pregnancy and postpartum factors.

Our results indicate that the Random Forest model

achieved the highest accuracy and precision at 96%

and 99%, respectively, utilizing a comprehensive set

of 42 variables. Between the two models tested, there

is no significant difference in accuracy and precision;

the difference is less than 0.3%. However, selecting

15 variables will make it easier for practitioners to

track them, and it won’t mean a risk.

Implementing machine learning models to predict

PPD risk can significantly impact the improvement of

maternal health by enabling early and personalized

preventive interventions. This approach can

contribute to reducing the economic and social

burden associated with PPD, enhancing the quality of

life for mothers and their families. Future research

could focus on integrating these models into

healthcare systems to maximize their applicability

and effectiveness.

REFERENCES

“Accuracy vs. Precision vs. Recall in Machine Learning:

What’s the Difference?” https://www.evidentlyai.

com/classification-metrics/accuracy-precision-recall

(October 9, 2024).

Amit, Guy, Irena Girshovitz, Karni Marcus, Yiye Zhang,

Jyotishman Pathak, Vered Bar, and Pinchas Akiva.

2021. “Estimation of Postpartum Depression Risk from

Electronic Health Records Using Machine Learning.”

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 21(1): 630.

doi:10.1186/s12884-021-04087-8.

“Baby Blues and Postpartum Depression: Mood Disorders

and Pregnancy.” 2024. https://www.hopkinsmedi

cine.org/health/wellness-and-prevention/post partum-

mood-disorders-what-new-moms-need-to-kn ow (June

12, 2024).

Bermúdez Serrano, Mercedes María. 2024. “Relación entre

la depresión postparto y la mala calidad del sueño

durante el embarazo y el postparto.” http://crea.uj

aen.es/jspui/handle/10953.1/23233 (July 16, 2024).

Bjertrup, Anne Juul, Mette Skovgaard Væver, and Kamilla

Woznica Miskowiak. 2023. “Prediction of Postpartum

Depression with an Online Neurocognitive Risk

Screening Tool for Pregnant Women.” European

Neuropsychopharmacology 73: 36–47. doi:10.1016/

j.euroneuro.2023.04.014.

CDC. 2024. “PRAMS Data.” Pregnancy Risk Assessment

Monitoring System (PRAMS). https://www.cdc.gov/

prams/php/data-research/index.html (July 17, 2024).

Hagatulah, Naela, Emma Bränn, Anna Sara Oberg, Unnur

A. Valdimarsdóttir, Qing Shen, and Donghao Lu. 2024.

“Perinatal Depression and Risk of Mortality:

Nationwide, Register Based Study in Sweden.” BMJ

384: e075462. doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-075462.

Health, MGH Center for Women’s Mental. 2020. “New

Study Estimates the Astonishing Cost of Neglected

Perinatal Mood and Anxiety Disorders in US Mothers -

MGH Center for Women’s Mental Health.”

https://womensmentalhealth.org/posts/cost-pmads/,

https://womensmentalhealth.org/posts/cost-pmads/

(July 16, 2024).

Hoyert, Donna L. 2024. “Maternal Mortality Rates in the

United States, 2022.”

Jin, Haomiao. 2015. “Development of a Clinical

Forecasting Model to Predict Comorbid Depression

Among Diabetes Patients and an Application in

Depression Screening Policy Making.” Preventing

Chronic Disease 12. doi:10.5888/pcd12.150047.

Kessler, R. C., H. M. van Loo, K. J. Wardenaar, R. M.

Bossarte, L. A. Brenner, T. Cai, D. D. Ebert, et al. 2016.

“Testing a Machine-Learning Algorithm to Predict the

Persistence and Severity of Major Depressive Disorder

from Baseline Self-Reports.” Molecular Psychiatry

21(10): 1366–71. doi:10.1038/mp.2015.198.

“Maternal Health.” https://www.who.int/health-topics/

maternal-health (July 16, 2024).

“Maternal Mortality Rates and Statistics.” UNICEF DATA.

https://data.unicef.org/topic/maternal-health/ maternal-

mortality/ (July 30, 2024).

Matsumura, Kenta, Kei Hamazaki, Haruka Kasamatsu,

Akiko Tsuchida, and Hidekuni Inadera. 2025.

“Decision Tree Learning for Predicting Chronic

Postpartum Depression in the Japan Environment and

Children’s Study.” Journal of Affective Disorders 369:

643–52. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2024.10.034.

Natarajan, Sriraam, Annu Prabhakar, Nandini Ramanan,

Anna Bagilone, Katie Siek, and Kay Connelly. 2017.

“Boosting for Postpartum Depression Prediction.” In

2017 IEEE/ACM International Conference on

Connected Health: Applications, Systems and

ICORES 2025 - 14th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

262

Engineering Technologies (CHASE), 232–40.

doi:10.1109/CHASE.2017.82.

“Postpartum Depression Statistics | Research and Data On

PPD (2024).” 2024. PostpartumDepression.org.

https://www.postpartumdepression.org/resources/statis

tics/ (July 30, 2024).

“Postpartum Depression Types - Pyschosis, OCD, PTSD,

Anxiety and Panic.” 2023. PostpartumDepression. org.

https://www.postpartumdepression.org/post partum-

depression/types/ (July 31, 2024).

Shin, Dayeon, Kyung Ju Lee, Temidayo Adeluwa, and

Junguk Hur. 2020. “Machine Learning-Based

Predictive Modeling of Postpartum Depression.”

Journal of Clinical Medicine 9(9): 2899. doi:10.3390/

jcm9092899.

Slomian, Justine, Germain Honvo, Patrick Emonts, Jean-

Yves Reginster, and Olivier Bruyère. 2019.

“Consequences of Maternal Postpartum Depression: A

Systematic Review of Maternal and Infant Outcomes.”

Women’s Health 15: 1745506519844 044. doi:10.1177/

1745506519844044.

“What Is Postpartum Depression? | UNICEF Parenting.”

https://www.unicef.org/parenting/mental-health/what-

postpartum-depression (July 16, 2024).

APPENDIX

Table 4 shows the remaining 27 variables considered in the original set of 42 variables for the analysis:

Table 4: Obtained results from scenario 1 (42 variables).

Variable

Scale

Measurement

Levels of measurement

His

p

anic ethnic

g

rou

p

Binar

y

YES = 1, NO = 0

Marital Status Cate

g

orical 1 = MARRIED, 2 = OTHER

Lan

g

ua

g

e Cate

g

orical 1=ENGLISH, 2=SPANISH, 3=CHINESE

Maternal race grouped Categorical

1=WHITE, 2=BLACK, 3=AM INDIAN, 4=AK

NATIVE, 5=ASIAN, 6=HAWAIIAN/OTH PAC

ISLNDR, 7=OTHER/MULTIPLE RACE

High blood pressure before pregnancy Binar

y

YES = 1, NO = 0

Depression before pregnancy Binary YES = 1, NO = 0

Asthma before pregnancy Binary YES = 1, NO = 0

Anxiety before pregnancy Binary YES = 1, NO = 0

Anemia before

p

re

g

nanc

y

Binar

y

YES = 1, NO = 0

Heart

p

roblems before

p

re

g

nanc

y

Binar

y

YES = 1, NO = 0

Infertility treatment Binary YES = 1, NO = 0

Number of prenatal care visits Categorical

1 = 1-10 visits, 2 = 11-20 visits, 3 = 21-30 visits, 4 = 31-

40 visits, 5 = 41-50 visits

Start PNC in 1

st

trimester Binary YES = 1, NO = 0

Mother get WIC food during pregnanc

y

Binary YES = 1, NO = 0

Hi

g

h blood

p

ressure durin

g

p

re

g

nanc

y

Binar

y

YES = 1, NO = 0

Vacuum deliver

y

Binar

y

YES = 1, NO = 0

Infant bein

g

breast-fe

d

Binar

y

YES = 1, NO = 0

Postpartum visits checkup Binary YES = 1, NO = 0

Breastfeed ever Binary YES = 1, NO = 0

Abused by husband during pregnancy Binary YES = 1, NO = 0

Abused b

y

ex-husband durin

g

p

re

g

nanc

y

Binar

y

YES = 1, NO = 0

If drinkin

g

alcohol Binar

y

YES = 1, NO = 0

If smoke three months before pregnancy Binary YES = 1, NO = 0

If smoke last three months of pregnancy Binary YES = 1, NO = 0

If smokes now Binary YES = 1, NO = 0

How often ecig used three months before

pregnant

Categorical

1=MORE THAN ONCE A DAY, 2=ONCE A DAY

3=2-6 DAYS A WEEK, 4=1 DAY A WEEK OR LESS,

5=NOT USE ELECTRONIC VAPOR PRODUCTS

How often ecig use the last three months Categorical

1=MORE THAN ONCE A DAY, 2=ONCE A DAY,

3=2-6 DAYS A WEEK, 4=1 DAY A WEEK OR LESS,

5=NOT USE ELECTRONIC VAPOR PRODUCTS

Predicting Postpartum Depression in Maternal Health Using Machine Learning

263