An Airline Profit Management Model with

Overbooking and No-Shows

Elias Olivares-Benitez

1a

, Ana Paula Orozco Esparza

2

, Juan Orejel

1b

and Catya Zuniga

3c

1

Faculty of Engineering, Universidad Panamericana, Alvaro del Portillo 49, Zapopan 45010, Mexico

2

Faculty of Business Administration and Economics, European University Viadrina, Frankfurt (Oder), Germany

3

Faculty of Technology, Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Keywords: Airline Profit, Overbooking, No-Show, Seat Inventory, Airplane Selection.

Abstract: This research presents a model for airline profit optimization considering information such as demand

forecasts, seat inventory, operational costs, overbooking penalties, expected no-shows, and time-dependent

fare classes. The main decisions in the model are the selection of the aircraft, the number of seats sold per

fare, including overbooking, and the number of denied seats. The model incorporates probabilistic information,

like the expected demand and the expected proportion of no-shows. The model is constructed as a

deterministic mixed-integer program. Some data was estimated using information acquired from different

industry sources, and some data was set with reasonable estimations. A factorial experiment was designed to

understand the importance of different parameters. The input variables were the overbooking compensation

penalty, the no-show probabilities per fare and time block, and the seat demand. Using a statistical analysis,

it was determined that the no-show estimation has the most significant impact on the total revenue, and the

demand forecast after that. These results highlight the importance of precise estimations to increase the

airline’s profit.

1 INTRODUCTION

The airline industry is a vital engine for the global

economy, facilitating international trade, tourism, and

cultural exchange. By connecting countries and

fostering stronger diplomatic and economic ties, the

industry plays a pivotal role in enabling both the

movement of people and goods across borders.

Airlines act as critical links in the global supply chain,

ensuring the smooth transport of essential goods and

services. This role becomes especially important in an

increasingly interconnected world, where efficient air

transportation can bolster trade partnerships and

enhance supply chain resilience.

Managing flight operations in such a complex,

globalized industry requires airlines to consider a

wide range of factors. Key variables like flight

schedules, passenger capacity, routes, and market

demand must be balanced to ensure efficient and

profitable operations. The rapid evolution of the

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7943-3869

b

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-4882-6057

c

https://orcid.org/0009-0004-2327-1337

market has driven the adoption of modern

technologies and sophisticated frameworks. This shift

has allowed airlines to not only streamline their

operations but also develop advanced pricing

strategies to remain competitive in a crowded market.

One of the central techniques used to manage this

complexity is profit management, which optimizes

the relationship between supply and demand by

adjusting ticket prices, seat availability, and

operational expenses based on real-time market

conditions. Some parameters that must be considered

for the balance of ticket pricing and seat allocation are

customer segmentation, seat capacity, and the

handling of cancellations and no-shows. In

anticipation of no-shows and last-minute

cancellations, airlines often sell more tickets than the

actual number of available seats. This approach,

while beneficial in maximizing revenue, introduces a

risk of penalties when too many passengers show up

and there are insufficient seats. However, research

264

Olivares-Benitez, E., Esparza, A. P. O., Orejel, J. and Zuniga, C.

An Airline Profit Management Model with Overbooking and No-Shows.

DOI: 10.5220/0013159900003893

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems (ICORES 2025), pages 264-270

ISBN: 978-989-758-732-0; ISSN: 2184-4372

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

shows that the revenue generated from overbooking

usually outweighs the costs associated with

compensating passengers who are denied boarding

(Rothstein, 1985; Ely et al., 2017). This practice

exemplifies the delicate balancing act airlines must

perform between profitability and customer service.

The effective management of overbooking

requires sophisticated modeling, especially when

cancellations and no-shows are factored in. Airlines

often use data-driven methods, relying on historical

data and forecasting tools to predict demand and

cancellations accurately. Studies such as those by

(Subramanian et al., 1999) and (Minga et al., 2003)

highlight various models that airlines employ to

manage these uncertainties. By optimizing booking

limits based on real-time and historical data, airlines

can minimize losses while ensuring they meet

customer demand. Algorithms and adaptive methods,

like those developed by (Ball and Queyranne, 2009),

have proven effective in refining demand estimates

and setting optimal booking limits.

The application of linear programming has been a

common thread across numerous studies in the airline

sector, emphasizing its importance in optimizing both

passenger and cargo operations. (Belobaba, 1987)

explored fare segmentation, showing how airlines

adjust ticket pricing based on advance bookings. This

segmentation allows airlines to offer lower fares to

early bookers while limiting the number of tickets in

each fare class to prevent financial losses. (Belobaba

et al., 2009) also noted that over 30% of denied

boarding requests result from passengers seeking

alternatives after being denied a seat, reflecting the

complexity of managing demand and ticket sales.

(Kunnumkal et al., 2012) delved into

overbooking, a widespread practice where airlines

sell more tickets than available seats, accounting for

potential no-shows. They employed randomized

linear programming to model overbooking scenarios

and no-shows, providing a strategy that helps airlines

maximize profits while minimizing the risk of unsold

seats. Introducing an upper bound criterion in their

research helps airlines determine the optimal

overbooking levels, mitigating financial losses from

customer no-shows.

(Aydin et al., 2013) study some dynamic

programming models for airline revenue

management considering overbooking and no-shows.

(Soleymanifar, 2019) addresses four constraints

relevant to airline revenue management problem:

flight cancellation, customer no-shows, overbooking,

and refunding. They develop a linear program closely

related to the dynamic program formulation of the

problem, which is later used to approximate the

optimal decision rule for rejecting or accepting

customers. Although Dynamic Programming is the

preferred approach used in the literature, there are

some linear programming formulations close to the

one proposed in this work in (Gaul and Winkler,

2019), (Gaul and Winkler, 2019), and (Xiao et al.,

2024).

In this research, we extend the model proposed by

(Kunnumkal et al., 2012) and originally presented by

(Bertsimas and Popescu, 2003) to incorporate some

elements like the selection of the aircraft based on

costs and capacities and an ethical control on the

overbooking. We also present a sensitivity analysis

with variations to a base instance to understand the

significance of the parameters on the profit objective

function. The main contributions of this paper are the

inclusion of aircraft selection and ethical

overbooking, along with the use of a design of

experiments to study the significance of some

parameters on the total profit.

The structure of the rest of the paper is described

next. The Methodology in Section 2 explains the

description of the problem, the mathematical model

proposed, and the data used for the case study.

Section 3 describes the results of the base instance

and the results of the sensitivity analysis using a

design of experiments. Section 4 shows the main

conclusions of the study and the proposed future

work.

2 METHODOLOGY

In this problem, we have different types of aircrafts,

with different capacities and operational costs. The

seats of the aircraft are divided by fare classes, and

each class has a fare that changes as time passes. Time

is “discretized” as time blocks, with the main idea

being that once the seats for a time block are sold, the

price increases when the time block is closer to the

departure time. Some important parameters

independent of the decision-making are the

compensation fee for denied boarding, the expected

demand of seats for fare class and time block, the

probability of no-shows for seats sold per time block

and fare class. Other parameters, dependent on the

decision-making are the fares for class and time

block, the maximum portion of sold seats that show

for check-in and are denied boarding, and the

minimum capacity to cover for an aircraft to be

operated. The variables are the seats sold, the denied

boarding seats, both per aircraft, fare class, and time

block, and the variable that determines the operation

An Airline Profit Management Model with Overbooking and No-Shows

265

of the aircraft. Following is shown the list of sets,

parameters and variables.

Sets:

J Set of products (fare classes), j = 1, ..., n

T Set of time blocks, t = 1, …, T

I Set of aircrafts, i = 1, …, |I|

Parameters:

f

ijt

price of fare class j in aircraft i in time block t

θ

ij

penalty for denying boarding of fare class j in

aircraft i

u

i

fixed cost for operating flight in aircraft i

q

jt

show probability for a seat (passenger) in fare

class j sold in time block t

c

ij

seat capacity for fare class j in aircraft i

p

jt

expected demand for fare class j sold in time

block t

α maximum proportion of sold (shown) seats

with denied boarding

β minimum capacity utilization to operate one

aircraft

Variables:

y

ijt

seats in aircraft i for fare class j sold in time

block t

w

ijt

denied boardings (seats) in aircraft i for fare

class j sold in time block t

v

i

binary variable, equal to 1 if aircraft i is

operated, equal to 0 otherwise

With these variables, a mixed-integer program is

constructed to maximize the profit with the following

objective function and constraints:

𝑀𝑎𝑥

𝑓

𝑦

−𝜃

𝑤

∈,∈, ∈

−𝑢

∈

𝑣

(1)

Subject to:

𝑞

𝑦

−𝑤

∈

≤𝑐

𝑣

,∀𝑖∈𝐼,

𝑗

∈

𝐽

(2)

𝑦

∈

≤𝑝

,∀

𝑗

∈

𝐽

,𝑡∈𝑇

(3)

𝑤

≤𝛼𝑞

𝑦

, ∀𝑖∈𝐼,

𝑗

∈

𝐽

,𝑡∈𝑇

(4)

𝑞

𝑦

−𝑤

∈,∈

≥

𝛽𝑐

∈

𝑣

,∀𝑖∈𝐼

(5)

𝑦

,𝑤

∈𝑍

, ∀𝑖∈𝐼,

𝑗

∈

𝐽

,𝑡∈𝑇

(6)

𝑣

∈

0,1

, ∀𝑖∈𝐼

(7)

In this model, the objective function (1)

determined that the profit is the sum of the sold seats

minus the penalty for denied boarding, all minus the

operational cost of selecting certain aircraft for the

flight. Constraints (2) are the constraints for not

exceeding the seat capacity per aircraft. Constraints

(3) establish that the number of sold seats does not

exceed the demand. Constraints (4) determine that the

seats (passengers) that show for check-in whose

boarding is denied do not exceed a certain proportion

of the seats sold, controlled by parameter

α

.

Constraints (5) help to ensure that a certain capacity

of the aircraft is sold to operate the flight. Constraints

(6) and (7) are the domains for the integer and binary

variables.

The model considers both overbooking and no-

shows, with constraints ensuring capacity limits are

respected. The number of seats denied boarding

should not exceed a certain percentage of total sales.

The introduction of binary variables accounts for

whether a flight will operate based on a threshold

capacity to ensure flights only operate when

economically viable. This constraint prevents

revenue losses due to low-demand flights.

Even after accounting for no-shows, seat sales

may exceed the available capacity on certain flights,

forcing airlines to deny boarding to some passengers.

This scenario suggests collaboration between airlines

to accommodate denied passengers. If the

compensation fee for denied boarding is too cheap,

there is an incentive for a high overbooking. In this

case, the “ethical selling” constraint in Equation (4)

prevents an excess of boarding denials.

The model was programmed in AMPL, using

Gurobi 10.0.1 as the optimizer, and solved in a laptop

with Intel Core i7 CPU at 2.8GHz with 32 Gb RAM.

An instance was constructed based on an example

flight. A one-leg-based approach is adopted for

simplicity, for the Frankfurt-Mexico City route. The

flight can be done in 4 different aircraft with the

capacities shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Aircraft capacities per fare class.

Aircraft Econom

y

Econom

y

Plus Business

Boeing

747-8

244 32 80

Airbus

A320

96 48 -

Embraer

E-170

56 - 20

Embraer

E-175

60 8 20

The fares for the flights for each aircraft and class

are shown in Table 2.

ICORES 2025 - 14th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

266

Table 2: Fare per aircraft and class, in €.

Aircraft Econom

y

Econom

y

Plus Business

Boeing

747-8

413 663 1288

Airbus

A320

351 521 -

Embraer

E-170

425 - 1159

Embraer

E-175

339 389 1154

The sale of seats was divided into three time

blocks. The fare per class increases 50% from the first

to the second time block, and it increases 70% from

the first to the third block. The third block is closer to

the departure time scheduled for the flight. The base

compensation fee for denying boarding is the ticket

fare plus 600 €. The operational costs for the flight in

the different aircraft are estimated from information

of (EUROCONTROL, 2023), shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Operational costs, in €.

Aircraft O

p

erational cost

Boein

g

747-8 189265

Airbus A320 105542

Embraer E-170 268065

Embraer E-175 105542

In the base instance, the demand was assumed the

same as the available capacity per fare class. This

demand was divided into a proportion of 30% for the

first time block, 30% for the second time block, and

40% for the third time block. The parameters

determined by the decision maker were set to α = 0.1

for the maximum seats with denied boarding, and β =

0.7 for the minimum capacity threshold for using a

certain aircraft.

The proportion of “shows”, i.e., the passengers

who bought a seat and who showed up to check-in at

the airport or who did not cancel their purchase, is

shown in Table 4. Since the fares are more expensive

in the last time block, closer to the departure time, the

proportion of no-shows is lower.

Table 4: Proportion of “shows” for check-in.

Fare class Time

b

lock 1

Time

b

lock 2

Time

b

lock 3

Econom

y

0.6 0.6 0.75

Econom

y

Plus 0.7 0.7 0.85

Business 0.8 0.8 0.95

3 RESULTS

For the base instance, the results are summarized in

Table 5. Only the flight operated by the Boeing 747-

8 was selected. Table 5 shows the number of seats

planned to be sold for this aircraft per fare class and

time block. The behavior of the passengers is to

consume the cheapest seats first, thus depleting the

seats planned for sale in the first time block. Once

those seats are sold, the fare is changed to the next

time block, with a more expensive price. After the

seats of this block are sold, the fare changes again,

being more expensive closer to the departure time.

Table 5: Seats sold per fare class and time block.

Fare class Time

b

lock 1

Time

b

lock 2

Time

b

lock 3

Econom

y

42 137 182

Economy Plus 0 15 17

Business 7 36 48

Because of the proportion of no-shows, even if the

number of sold seats exceeds the capacity of the

aircraft, there is no need to deny boarding because of

the overbooking. The expected profit was 268197 €

for this flight. When the demand is high, and more

than one aircraft is selected for a flight, a negotiation

with the airport may allow different flights operated

with different aircrafts with a short difference in the

departure times.

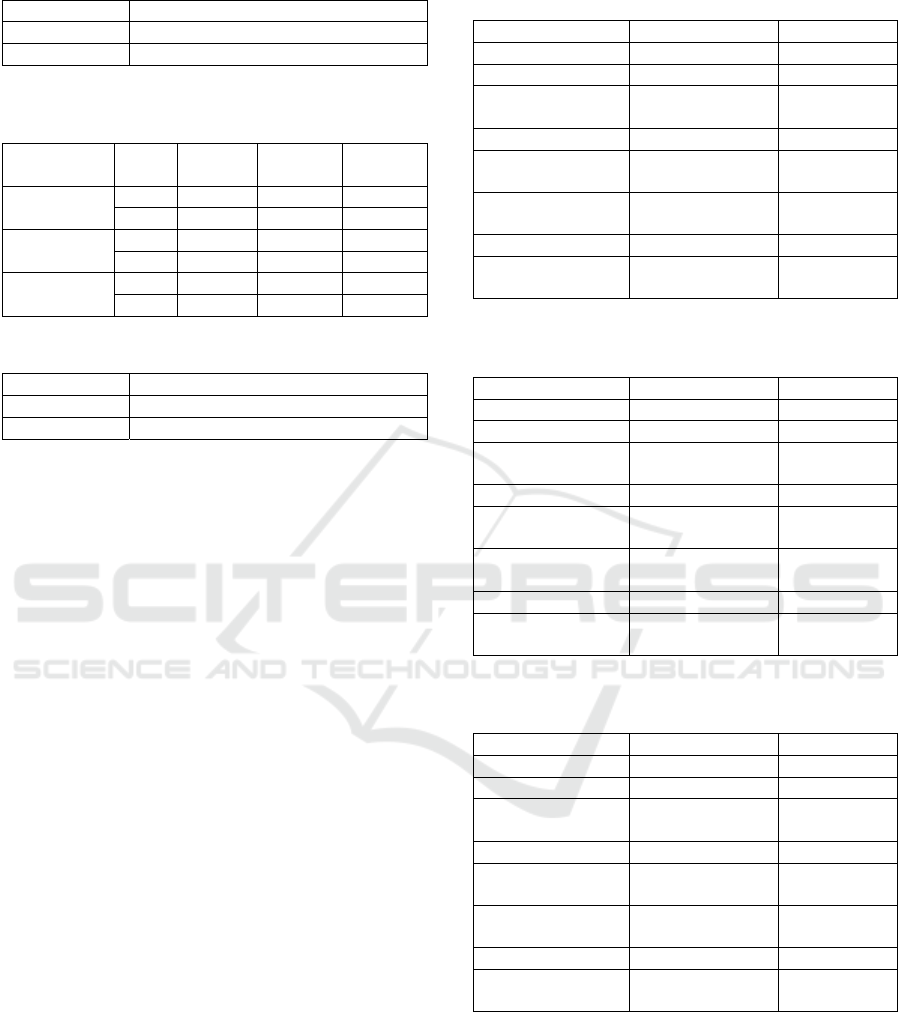

A factorial experiment was designed to

understand the impact of changes in some parameters.

Three parameters were modified, the compensation

fee for denying boarding to a sold seat, the no-show

proportion per fare class and time block, and the

expected demand. Table 6 shows the low and high

levels for the compensation fee with respect to the

base instance. These levels were explored because the

base instance did not deny boarding to overbooked

seats, and we wanted to know if the fee reduction may

incentivize boarding denials. Table 7 shows the low

and high levels for the “show” proportion. These

levels were set to explore the effect of the variability

in the no-shows. The high level is the combination of

“high” for all the fare classes, and the same happens

for the “low” level. Table 8 shows the low and high

levels for the change of demand with respect to the

base instance. These levels were set considering

periods of high demand, like holidays and vacations.

An Airline Profit Management Model with Overbooking and No-Shows

267

Table 6: Low and high levels for the compensation fee.

Level Chan

g

e in the com

p

ensation fee

Low 25%Ticket

p

rice + 600EUR

Hi

g

h 50%Ticket

p

rice + 600EUR

Table 7: Low and high levels for the proportion of “shows”

for check-in.

Fare class Level Time

b

lock 1

Time

b

lock 2

Time

b

lock 3

Economy Low 0.55 0.55 0.70

Hi

g

h 0.65 0.65 0.80

Economy

Plus

Low 0.65 0.65 0.80

Hi

g

h 0.75 0.75 0.90

Business Low 0.75 0.75 0.90

High 0.85 0.85 1.00

Table 8: Low and high levels for the demand.

Level Chan

g

e in the deman

d

Low +40% in ever

y

p

erio

d

High +70% in every perio

d

Thus, a full factorial of 2

3

experiments was run.

Table 9 summarizes the averages of the instances

with the high and low levels of the compensation fee.

Table 10 summarizes the averages of the instances

with the high and low levels of the “show” rate. Table

11 summarizes the averages of the instances with the

high and low levels of demand. The output variables

are:

Total profit;

%sale per fare class, i.e. the proportion of seats

sold from the expected demand;

%denied per fare class, i.e. the proportions of

denying boarding seats from the total of sold

seats;

%average aircraft utilization, i.e. the proportion

of seats used from the available capacity.;

The results for some instances indicated that more

than one aircraft should be selected. It becomes

evident that this is necessary for periods of high

demand where additional capacity is needed. In this

case, the averages reported consider the accumulated

quantities for all the aircraft selected.

As can be observed, an increase in the

compensation fee and the proportion of “shows”

reduce the total profit. And a high demand increases

the profit. In all the cases, the levels proposed

generated some denied boarding seats. In all the

cases, the aircraft utilization is above 99%.

Table 9: Averages of instances with high and low levels of

the compensation fee.

Output variable Low level High level

Total profit 314841.96 308618.93

%sale Econom

y

76.22 72.26

%sale Economy

Plus

80.88 77.03

%sale Business 54.44 54.44

%denied

Econom

y

3.48 0.34

%denied

Econom

y

Plus

5.12 2.12

%denied Business 7.91 7.91

%average aircraft

utilization

99.95 99.88

Table 10: Averages of instances with high and low levels of

the show (no-show) levels.

Output variable Low level High level

Total

p

rofit 348354.02 275106.87

%sale Econom

y

80.83 67.65

%sale Economy

Plus

84.70 73.21

%sale Business 57.39 51.48

%denied

Econom

y

2.36 1.45

%denied

Economy Plus

3.37 3.87

%denied Business 7.48 8.33

%average aircraft

utilization

99.92 99.92

Table 11: Averages of instances with high and low levels of

the show (no-show) levels.

Out

p

ut variable Low level Hi

g

h level

Total

p

rofit 303622.76 319838.13

%sale Econom

y

80.99 67.49

%sale Economy

Plus

86.20 71.71

%sale Business 59.12 49.76

%denied

Econom

y

1.05 2.76

%denied

Economy Plus

2.38 4.86

%denied Business 7.98 7.83

%average aircraft

utilization

99.87 99.97

The results were analyzed statistically using an

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) assuming normal

distributions of the output variables. The results are

shown in Table 12.

ICORES 2025 - 14th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

268

Table 12: P-values for the ANOVA.

Output

variable

Compensation

fee

“Shows”

p

roportion

Demand

Total

p

rofit >0.05 0.008 0.038

%sale

Econom

y

>0.05 >0.05 >0.05

%sale

Economy

Plus

0.002 0.001 0.001

%sale

Business

>0.05 <0.001 <0.001

%denied

Econom

y

>0.05 >0.05 >0.05

%denied

Economy

Plus

0.022 >0.05 0.027

%denied

Business

>0.05 <0.001 <0.001

%average

aircraft

utilization

0.021 >0.05 0.015

The results obtained are mixed, but it can be

observed that the no-shows and the demand have a

significant impact on the Total profit and on the sales

of the most expensive fare classes.

4 CONCLUSIONS

This study used a deterministic model approach to

maximize total airline revenue, focusing primarily on

overbooking, passenger no-shows, operating costs,

demand, and capacity. The model also incorporated

compensation fees for denying boarding, which

influenced decision-making. The data estimated for

this case study enabled a sensitivity analysis, which

identified the parameters that significantly impact

profit. After running the tests, it was determined that

the compensation fee had minimal effect on profit,

while show probability and demand were the most

influential factors. Accurate demand forecasting and

no-show rates are crucial for airlines to ensure

positive profit. The main contributions of this paper

are the inclusion of aircraft selection and ethical

overbooking in a previously published optimization

model, along with the use of a design of experiments

to study the significance of some parameters on the

total profit.

However, some limitations emerged in the study.

The demand was based on fictional variations due to

a lack of prior data. Airlines with access to historical

flight data can use realistic variations and

complement these with no-show rates to better

estimate denied boarding. Another challenge was

estimating fixed or operational costs, which were

sourced from publicly available information.

Additionally, many airlines have agreements with

other carriers to accommodate denied boarding

passengers, offering discounted fees in such cases.

Future work could explore more advanced

scenarios, such as multiple flight legs, integrating

different aircraft capacities, hubs, and nested or non-

nested seat allocation. Additionally, varying the time

range could also enhance the model’s applicability.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by Universidad

Panamericana through grant [UP-CI-2024-GDL-08-

ING].

REFERENCES

Aydın, N., Birbil, Ş. İ., Frenk, J. B. G., Noyan, N. (2013).

Single-Leg Airline Revenue Management with

Overbooking. Transportation Science, 47(4), 560–583.

DOI: 10.1287/trsc.1120.0444

Ball M.O., Queyranne M. (2009). Toward robust revenue

management: Competitive analysis of online booking.

Operations Research, 57 (4), 950 – 963. DOI:

10.1287/opre.1080.0654

Belobaba, P. (1987). Air travel demand and airline seat

inventory management (thesis). Massachusetts Institute

of Technology, Massachusetts.

Belobaba, P., Odoni, A. R., Barnhart, C. (2009). The Global

Airline Industry. John Wiley & Sons.

Bertsimas, D., Popescu, I. (2003). Revenue management in

a dynamic network environment. Transportation

Science, 37(3), 257–277. DOI: 10.1287/trsc.37.

3.257.16047

Ely, J.C., Garret D.F., Hinnosaar, T. (2017). Overbooking.

Journal of the European Economic Association, 15(6),

1258–1301. DOI: 10.1093/jeea/jvw025

EUROCONTROL (2023). EUROCONTROL Standard

Inputs for Economic Analyses. Available at

[12/05/2023]: https://ansperformance.eu/economics/

cba/standard-inputs/

Gaul, W., Winkler, C. (2019). Aviation Data Analysis by

Linear Programming in Airline Network Revenue

Management. In: Bauer, N., Ickstadt, K., Lübke, K.,

Szepannek, G., Trautmann, H., Vichi, M. (eds)

Applications in Statistical Computing. Studies in

Classification, Data Analysis, and Knowledge

Organization. Springer, Cham. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-

030-25147-5_1

Gaul, W., Winkler, C. (2020). Flight Passenger Behavior

and Airline Fleet Assignment. In: Imaizumi, T.,

Nakayama, A., Yokoyama, S. (eds) Advanced Studies

in Behaviormetrics and Data Science.

An Airline Profit Management Model with Overbooking and No-Shows

269

Behaviormetrics: Quantitative Approaches to Human

Behavior, vol 5. Springer, Singapore. DOI:

10.1007/978-981-15-2700-5_4

Kunnumkal, S., Talluri, K., & Topaloglu, H. (2012). A

randomized linear programming method for network

revenue management with product-specific no-shows.

Transportation Science, 46(1), 90–108. DOI:

10.1287/trsc.1110.0386

Minga L.M., Feng Y.-Q., Li Y.-J. (2003). Dynamic pricing:

Ecommerce - Oriented price setting algorithm.

International Conference on Machine Learning and

Cybernetics, 2, 893 – 898.

Rothstein, M. (1985). OR AND THE AIRLINE

OVERBOOKING PROBLEM. Operations Research,

33 (2), 237 – 248. DOI: 10.1287/opre.33.2.237

Soleymanifar, R. (2019). An LP based approximate

dynamic programming model to address airline

overbooking under cancellation, refund and no-show.

Yugoslav Journal of Operations Research, 29(1), 113–

133. DOI: 10.2298/yjor170918026s

Subramanian, J., Stidham, S., Lautenbacher, C. J. (1999).

Airline yield management with overbooking,

cancellations, and no-shows. Transportation Science,

33(2), 147–167. DOI: 10.1287/trsc.33.2.147

Xiao, F., Lai, K. K., Lau, C. K., & Ram, B. (2024). Robust

Overbooking for No-Shows and Cancellations in

Healthcare. Mathematics, 12(16), 2563. DOI:

10.3390/math12162563

ICORES 2025 - 14th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

270