Sorting Circulating Tumor Cells: A Low Flow Microfluidic

Pre-Enrichment Function for Improved Separation

in Serial Two-Stage Sorting Device

Emma Dupont

1,2 a

, Emilie Laffont

1,2

, Marie Piecyk

3b

, Léa Payen

3c

, Clément Albin

2

,

Gilles Simon

2

, Damien Le Roy

2d

and Anne-Laure Deman

1e

1

Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, CNRS, INSA Lyon, Ecole Centrale de Lyon, CPE Lyon, INL, UMR5270 69621

Villeurbanne, France

2

Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, CNRS, Institut Lumière Matière, UMR5306, F-69100, Villeurbanne, France

3

Laboratoire de Biochimie Et Biologie Moléculaire, Groupe Hospitalier Sud, Hospices Civils de Lyon, 69495 Pierre Bénite,

France

Keywords: Cell Separation, Circulating Tumor Cells, Dean Vortices, Liquid Biopsy, Micro Milling, Microfluidic Device,

Passive Separation, Size Sorting, Spiral Microchannel.

Abstract: The isolation of Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs) directly from blood by liquid biopsy could lead to a paradigm

shift in clinical cancer care by enabling earlier diagnosis, more accurate prognosis and personalized treatment.

Nevertheless, the specific challenges of CTCs, including their rarity and heterogeneity, have so far limited

the use of CTCs in clinical studies. Currently, no device fully meets the requirements of high recovery, high

purity, short processing time and ease of use for end-users. A promising new strategy involves combining a

higher throughput but less specific pre-enrichment step based on size sorting together with a highly specific

but slower immunomagnetic sorting. This approach requires the initial function to operate at lower flow rates

than commonly used to connect the two functions in series. In this context, we developed a Dean spiral

microfluidic device, optimized for sorting 10µm and 15µm beads by size. We showed that it successfully

separates mimicking CTCs from white blood cells at low flow rates (<100 mL/h).

1 INTRODUCTION

Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) have been biomarkers

of interest to the medical community for many years.

Originating from the patient tumor and accessible by

blood sampling, they can be used to enhance our

understanding of metastasis dynamics, improve

cancer detection (through liquid biopsy) (Mazzitelli,

et al., 2023), prognosis assessment and refine

monitoring strategies (CellSearch, 2024). Despite the

appealing interests of CTCs, a major issue stands in

the way of their recovery. The CTC are extremely

rare in the blood: 1-1000 CTC per mL, i.e. 1-1000

CTC per 10

7

white blood cells (WBC) and 10

9

red

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-8381-3080

b

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-3765-9472

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1599-5886

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3111-6044

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9351-8703

blood cells (RBC) (Stoecklein, et al., 2016), making

the sorting complex. Moreover, CTC sorting must

fulfill some requirements. First, it must have a high

recovery rate (>90%): the fraction of CTCs being

very low in a blood sample, it is necessary to get the

maximum of them downstream of the process.

Secondly, the purity of the sample is also crucial. The

other blood cells are outnumbered compared to the

CTCs, and they may pollute the downstream analysis,

so the purity of the sorting must be high (>99,99%).

Additionally, it is important to preserve cell viability

during isolation.

Studies in the literature generally isolate CTCs

from other blood cells based on differences in their

biological or physical properties, such as surface

Dupont, E., Laffont, E., Piecyk, M., Payen, L., Albin, C., Simon, G., Roy, D. L. and Deman, A.-L.

Sorting Circulating Tumor Cells: A Low Flow Microfluidic Pre-Enrichment Function for Improved Separation in Serial Two-Stage Sorting Device.

DOI: 10.5220/0013162200003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 1, pages 163-170

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

163

marker expression or size, deformability, and

dielectric properties. In terms of biological properties,

two strategies are possible: positive enrichment by

labelling CTCs with magnetic nanoparticles or

negative depletion by labelling WBCs. However, not

all CTCs express the same markers on their surface,

so there is a risk of losing some of them by targeting

a specific marker. Furthermore, labelling WBCs with

anti-CD15 or anti-CD45 markers is not fully efficient,

and some WBCs remain non-magnetic. The

biological approach has therefore its limitations.

Alternatively, physical property differences can be

exploited to separate CTCs from other blood cells by

driving them into different outlets. This method offers

high throughput without any labelling steps, but if the

physical properties are too similar, a precise

separation is challenging. For instance, CTCs are

typically larger than WBCs and RBCs (Hou et al.,

2013). However, the overlapping size range between

CTCs and WBCs inevitably limits the purity of the

isolation process.

Much work has been published in the literature in

recent years on sorting CTCs in microsystems (Qiao,

et al., 2024) (Descamps, et al., 2022), and devices

have been commercialized (Parsortix PC1, ANGLE,

Genesis System, BIORAD; ClearCell FX1,

BIOLIDICS; VTX-1 Liquid Biopsy System,

VORTEX) but CTC analysis is still not routinely

carried out in hospitals. Indeed, despite significant

successes, isolation methods relying on a single

separation technique do not meet all the CTC sorting

requirements mentioned earlier. A promising

approach is to combine two different sorting methods

to make up for the shortcomings of each, using

physical separation method as a pre-enrichment step

followed by an immunomagnetic sorting step (Li, et

al., 2024) (Nian, et al., 2024) (Descamps, et al.,

2021).

Combining two functions in microfluidics is

challenging as each function optimally operates at a

different flow rate. In particular, hydrodynamic

devices often work at much higher flow rates than

immunomagnetic ones. In this work we set out to

develop a hydrodynamic pre-enrichment function

operating at low flow rates. Dean vortices have been

widely studied as a size-based CTC sorting technique,

using inertial microfluidics to position particles

within the channel based on their size. Different

systems have been developed yielding promising

results (Zhu, et al., 2024) (Akbarnataj, et al., 2023)

(Al-Halhouli, et al., 2018) at flow rates ranging from

100-300mL/h. Here we report on a design of Dean

flow device that operates at lower flow rates (<100

mL/h) compared to most spirals developed for CTC

sorting, and that can be used as a pre-enrichment step

prior to an immunomagnetic sorting step.

2 DEVICE FABRICATION

2.1 Microchannel Design

In rectangular straight microchannels, the equilibrium

position of a particle, in the section of the channel of

width 𝑤 and height ℎ, is mainly due to lift forces (Di

Carlo, et al., 2009):

𝐹

=

𝜌𝑈

𝑎

𝐷

𝑓

𝑅𝑒,𝑥

(𝑁)

(1

)

where 𝜌 is the fluid density, U the fluid mean velocity

(m/s), 𝑎

the particle diameter, and 𝐷

=𝑤ℎ/(𝑤+

ℎ) is the hydraulic diameter of the channel and 𝑓

a

lift coefficient ranged between 0.02-0.05, depending

on 𝑅𝑒 the Reynolds number and 𝑥

, the particle

position in the channel.

In curved channels, the curvature creates a

pressure gradient in the channel, which leads to the

formation of two counter-rotating vortices, known as

Dean vortices. In such vortices, a particle is submitted

to the Dean drag force, which can be expressed as (Di

Carlo, et al., 2007):

𝐹

=𝜌

𝑈

𝑎

𝐷

𝑅

(N)

(2

)

where R is the radius curvature of the spiral. The Dean

number De is often use to quantitively characterize

the strength of secondary flows in such channels:

𝐷𝑒=𝑅𝑒

𝐷

2𝑅

(3

)

The higher it is, the stronger are the secondary

vortices. A particle flowing in a spiral or curved

channel is then mainly subjected to 𝐹

and 𝐹

in the

section perpendicular to the main flow. The

competition between these two forces is often used to

describe the particle behavior and predict its

equilibrium positions in the channel section. It is

important, for particle size sorting, to note that both

forces depend on the particle diameter 𝑎

(𝐹

∼𝑎

and 𝐹

∼𝑎

). This results in two distinct behaviors:

bigger particles tend to focus at an equilibrium

position and remain in a specific location within the

channel’s section, while smaller particles tend to be

dragged into Dean's vortices and recirculate across

BIODEVICES 2025 - 18th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

164

the channel width (Bhagat A. A., et al., 2010), (Wu,

et al., 2012).

To effectively separate WBCs from CTCs in a

spiral microfluidic channel, we aim to focus the two

populations in separate locations of the channel

width. We have designed a spiral channel based on

key principles described in the literature.

First, to ensure proper particle focusing, we

considered the confinement ratio of the particle. As

outlined by Di Carlo et al. (2007), this ratio must

satisfy:

>0.07

(4)

to achieve proper focusing. Another critical

parameter is the ratio of lift forces to Dean forces, as

described by Amini et al. (2014). They established the

inequality:

𝑅

=

𝐹

𝐹

~

2𝑅𝑎

𝐷

>~0.08

(5)

This inequality, derived from their previous

experimental results and other study (Di Carlo, et al.,

2007), provides a guideline for selecting suitable

spiral geometry to achieve efficient particle focusing.

Secondly, a trapezoidal cross-section was selected

to enhance size-based separation across the channel.

This design introduces asymmetry in the flow profile,

which shifts the Dean vortices centres toward the outer

wall of the channel. As a result, smaller particles, such

as WBCs, entrained in the vortices, are pushed toward

the outer wall, whereas larger particles, like CTCs,

remain focused near the inner wall. This configuration

significantly improves the separation efficiency

between different size populations. (Wu, et al., 2012)

(Akbarnataj, et al., 2023).

In order to operate at lower flow rates, we

developed a spiral with a reduced cross-sectional area

compared to those reported in the literature. The

reduction in channel dimensions aims to achieve the

necessary velocities to generate Dean vortices at low

flow rates.

Based on these criteria, we designed a 6-loops

spiral with one inlet and two outlets, an internal radius

of 1 mm and a trapezoidal cross-section. The width w

of the channel is 250 µm, the height of the inner wall

of the channel is 60 µm and the height of the outer

one is 85 µm. The spacing between the windings is

equal to the width of the micro-channels.

2.2 Microsystem Fabrication Steps

To create a microchannel with a trapezoidal cross-

section, a mold with variable height was required.

The master mold was fabricated by micro-milling

(CNC Mini-Mill/3, Minitech Machinery

Corporation) on brass (Figure 1.A.1) in a two-step

process (Figure 1.B). First the horizontal contour of

the spiral has been milled using 500 µm and 200 µm

flat nose end mill. Secondly, the machining of the top

wall of the channel (which is inclined due to the

trapezoidal cross-section) was obtained

using a 200

µm diameter ball nose mill with z-axis steps of 1 µm.

A SEM-image and the profile (Dektak150, Veeco) of

the channel are shown in Figure 1.C and Figure 1.D.

The microchannels were then fabricated by casting

PDMS (Sylgard

Silicone Elastomer, 10:1 base and

curing agent mixing ratio) on the mold and curing it

at 65°C during 2 h (Figure 1.A.2). After curing, the

PDMS was peeled from the mold and plasma bonded

to a 1 mm thick flat glass slide to complete the

microchannel (Figure 1.A.5). Input and output ports

of 0.5 mm were punched prior to bonding step with

the Uni-Core TM Puncher. Figure 1.E shows a picture

of the PDMS final device.

3 MATERIALS AND METHODS

3.1 Sample Preparation

For bead experiments, fluorescent-polystyrene

particles with diameter of 10 μm (9.9 ± 0.09 μm,

blue), 15 μm (15.4 ± 0.139 μm, red) (Thermofisher

scientific), were diluted in Phosphate-buffered saline

(PBS). A solution containing both bead populations

was prepared with equal concentrations of 1.10

beads/mL for each population.

For cells and blood sample experiments, MDA-MB-

231 and MCF7 cells were cultured to mimic the CTC

in blood. The cells were stained with Hoechst

(1µL/mL, blue) for 15 minutes at 37°C, followed by

three centrifugation (1000 rpm, 5 minutes) and

resuspension (in 1xPBS) steps. The final

concentration used was 9.10

cells/mL (MDA) and

10.10

cells/mL (MCF7). All experiments involving

healthy blood samples were carried out in conformity

with the relevant French laws and institutional

guidelines and approved by the French national blood

collection institution, named “Etablissement Français

du Sang” (EFS). All healthy volunteers gave

informed consent for the collection of blood samples.

Blood samples were collected from healthy

volunteers into EDTA tubes (BD Vacutainer). Red

blood cells were first removed using a lysis buffer x

1 (EurX®, E0326-02). Following the manufacturer's

protocol, lysis buffer was added in a 1 : 4 v/v ratio

(blood/lysis buffer) and incubated for 10 min at room

Sorting Circulating Tumor Cells: A Low Flow Microfluidic Pre-Enrichment Function for Improved Separation in Serial Two-Stage Sorting

Device

165

temperature (RT) and then centrifuged at 500 × g for

10 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant,

containing lysed red blood cells, is discarded. The

WBCs, contained in the pellet, are stained with

Hoechst (1 µL/mL, blue) following the same steps as

for the MDA and MCF7 cells. The WBCs are counted

in Malassez cells at around 9.10

cells/mL. The

behaviors of the cell populations in the device were

characterized independently.

Figure 1: A) Device fabrication steps. 1) Micro-milling of

the brass mold, 2) Pouring and curing of PDMS 3)

Unmolding PDMS and 4) O

2

plasma treatment 5) bonding

on glass slide B) Picture of the brass mold C) 2D-Profil of

the spiral channel cross-section. The vertical distortion is

due to the stylus tip angle D) SEM picture of a 6

th

turn

portion and E) Picture of the final device in PDMS.

3.2 Acquisition Method

The different sample solutions have been injected in

the spiral channel with a syringe pump (DKInfusetek,

ISPLab02). Fluorescents images were recorded with

Thunder microscope (Leica Microsystems). The

fluorescence signal intensities for each bead

populations were extracted with ImageJ and

subsequently processed on MATLAB. On the

boxplots (Figure 2.B and Figure 4), the central mark

indicates the median value, and the bottom and top

edges of the box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles

of the intensity throughout the channel width,

respectively. The whiskers extend to the most

extreme data points not considered outliers.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Microbeads Separation

In this section, we aimed to separate the 10 µm and

15 µm bead populations into distinct, narrow streams

across the channel width. The following sections

focus on identifying the optimal conditions for

effective separation. To achieve that, we investigated

the bead trajectories at flow rates ranging from 10 to

120 mL/h.

4.1.1 Flow Rate Dependency of Bead

Positioning

Images of the spiral outlet were taken, just before the

bifurcation into two separate outlets, at various flow

rates, as depicted in Figure 2.A. Depending on the

flow rate, the beads were observed to focus into either

a single stream or two closely spaced streams.

When examining the focusing positions across the

channel width, both bead populations demonstrated

similar migration patterns (Figure

2.B), as reported in

the literature (Martel, et al. 2013) (Guan, et al., 2013).

At low flow rates (10–20 mL/h), the two bead

populations remained mixed and focused near the

channel center. As the flow rate increased, both

populations began migrating toward the inner wall of

the channel, but at different flow rates: the small 10

µm beads reached their most inner position at around

30 mL/h, while the large 15 µm beads reached this

position at higher flow rate, at around 60 mL/h. The

location of the inner equilibrium position also differs

between the two populations, with the larger beads

focusing closer to the inner wall than the smaller

ones. At even higher flow rates, both bead

populations migrated toward the outer wall of the

channel. This outward migration occurred at lower

flow rates for the 10 µm beads compared to the 15 µm

ones. By 120 mL/h, both populations have moved to

a similar position close the outer wall of the channel.

As suggested in the literature, this position may

correspond to the center of the Dean vortices (Wu, et

al., 2012).

Additionally, one can notice that at flowrate in

which the beads move through the channel section

(i.e. are not in a specific equilibrium position), the

observed focusing beam may widen or split into two

adjoining sub-beams.

BIODEVICES 2025 - 18th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

166

Figure 2: A) Superimposed images of the 10 µm (blue) and

15 µm (red) beads flowing through the last turn of the spiral.

B) Boxplot of the fluorescence intensity repartition in the

channel width, 0 µm being the outer wall and 250 µm the

inner one. C-E) Fluorescence intensity signal of the two

beads populations at the outlet at 45, 50 and 60 mL/h.

Since the transition of bead positions occurs at

different flow rates, we can identify the flow rates at

which the 10µm beads are positioned near the outer

wall, while the 15 µm beads remain near the inner

wall, allowing for separation. The bead streams are

separated at three flow rates: 45 mL/h, 50 mL/h and

60 mL/h. The corresponding florescent signals for

these flow rates are shown in figure 2.C-E. Most

beads in each population concentrate into a single

stream. However, some of them remain slightly

unfocused, and must be considered when determining

the optimal flow rate for separation.

The flow rate of 60 mL/h provides the best

separation, offering the largest gap between the two

populations while minimizing overlap caused by

unfocused beads.

4.1.2 Beads Focusing Along the Spiral

Beside flowrate analysis, the focusing of the beads

has also been investigated in the different turns of the

spiral. In the literature, the number of turns of the

spiral varies from 1 to 12 depending on the spiral

design. Amini et al (Amini, Wonhee, & Di Carlo,

2014) expressed the length 𝐿 required for particles to

reach their equilibrium positions:

𝐿=

𝑓

𝜋𝜇ℎ²

𝜌𝑈

𝑎²

𝑓

(𝑚)

(6

)

where 𝑈

the fluid max velocity in the channel (m/s).

To account for the shorter particle focusing distance

at high De values (typically De>17), the authors

introduces 𝑓, a scaling factor ranged from 0.2 to 1,

depending on the curving channel design, with a

value of 1 applied for lower De. For our design, at 60

mL/h, 𝐷𝑒 = 25. Using 𝑓=0.2 and according to

(6), the minimum distance for the 10 µm and 15 µm

beads to focus is 9 mm and 4 mm respectively.

According to our spiral dimensions, both populations

should be focused after the 2

nd

turn (

Table

1

).

Table 1: Length of the spiral at each turn.

Turn 1 2 3 4 5 6

Length

(mm)

4.3 13.7 26.3 42.0 60.9 82.9

Experimentally, the beads gradually focus into

their equilibrium position as they move through the

turns (Figure 3A). By the second turn, the 15 µm

beads are already tightly focused into a single stream,

whereas the 10 µm beads remain in a larger stream

(Figure 3B).

Figure 3: A-C) Picture of the beads solution flowing

throughout the turns at 60 mL/h. B-D) 10 µm (blue) and 15

µm (red) fluorescence intensity in the spiral turns from the

first one (left) to the 6

th

and last one (right).

As the beads move along the curved

microchannel, the positions of the two populations

progressively move apart, with one (15 µm) focusing

along the inner side of the channel and the other along

the opposite side, reaching maximum separation in

the final turn.

Sorting Circulating Tumor Cells: A Low Flow Microfluidic Pre-Enrichment Function for Improved Separation in Serial Two-Stage Sorting

Device

167

4.2 Device Performances on WBC and

Mimicking CTC

To mimic the behavior of CTCs in a microfluidic

spiral channel and investigate their separation from

WBCs, we characterized the behavior of MDA-MB-

231 cancer cells (average diameter 12-14 µm), MCF7

cancer cells (average diameter 18µm) commonly

used in the literature to mimic CTC (Macaraniag, et

al., 2023). We also circulated WBCs, whose sizes

vary significantly depending on their type, with an

average diameter ranging from 7 to 12 (Hou et al.,

2013), at flow rates ranging from 10 to 120 mL/h.

We first analyzed the lateral focusing and position

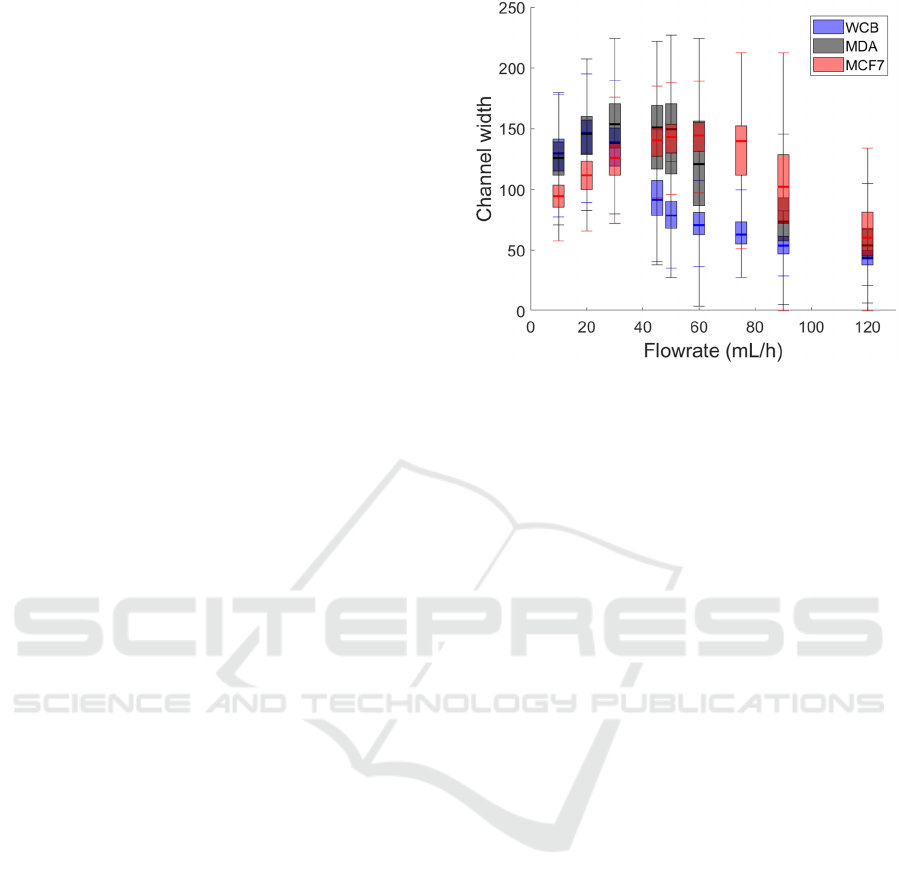

of these cells at the outlet, as shown in Figure 4. Even

if cells are deformable and vary in size (i.e., non-

monodisperse), all three cell types focused into

distinct single streams at the channel outlet across all

tested flow rates.

In terms of equilibrium positions within the

channel, all the cell types exhibited a behavior similar

to the one observed with beads. As the flow rate

increased, the cells initially migrated toward an

equilibrium position near the inner wall of the

channel and, at higher flow rates, they gradually

shifted toward the outer wall.

Interestingly, each cell type exhibited this

migration at different flow rates, correlating with

their size. WCBs reached their innermost equilibrium

position at a relatively low flow rate of around 20

mL/h, the slightly larger MDA-MB-231 cells reached

this position at approximately 45 mL/h, and the

largest ones, MCF7, focus near the inner wall at even

higher flow rates, around 60 mL/h. Notably, MDA-

MB-231 cells focused closer to the inner wall than

WBCs, consistent with the bead study findings based

on their size. While size-dependent behavior suggests

MCF7 cells would focus closer to the inner wall than

MDA, their inner position remained farther away,

likely due to the channel's spatial constraints (65 µm

height in this region). Additionally, it was observed

that the MDA cells focused in wider streams than the

other two cell populations.

Our results illustrate a clear size-dependent

behavior: smaller cells migrate toward the inner wall

at lower flow rates compared to larger cells, enabling

effective size-based cell separation. To separate

WBCs and MDA-MB-231 cells, the optimal flow rate

for maximum separation is 50 mL/h. The interquartile

distance between the two focused streams is then

approximately 22,5 µm, which is sufficient to direct

them into separate outlets at the channel exit.

Figure 4: Boxplot of the fluorescence intensity repartition

of 3 cell populations in the channel width.

This separation is even more pronounced at 60

mL/h between WBCs and MCF7 cells, given their

larger size difference. At this flow rate, MCF7 cells

remain at their innermost position, while WBCs have

already migrated outward, maintaining a 50 µm

interquartile distance. Although MCF7 cells are

commonly used to mimic CTCs due to their large

size, it is essential to consider both MCF7 and MDA-

MB-231 populations during sorting to best represent

the size diversity of the CTCs.

This size-dependent equilibrium positioning

enables the collection of different cell types based on

their distinct stream locations, ensuring efficient

separation of larger CTCs from smaller WBCs. This

isolation can be achieved with our spiral between 50

and 75mL/h, at lower flowrates than spirals in the

literature (Zhu, et al., 2024) (Akbarnataj, et al., 2023)

(Al-Halhouli, et al., 2018).

5 CONCLUSIONS

In a context of growing interest for CTC, the

combination, via a serial connection, of two

microfluidic functions (a pre-enrichment and a

sorting one) appears to be an efficient CTC sorting

strategy. This integrated approach necessitates that

the initial microfluidic system operates at low flow

rates (<100 mL/h), enabling it to function coherently

with the other microfluidic function. Our findings

demonstrate the successful development of a Dean

spiral microfluidic device that efficiently separates

particles depending on their size, in particular 10 µm

and 15 µm beads, at low flow rates. It is also effective

in sorting WBCs from mimicking CTCs in a range of

BIODEVICES 2025 - 18th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

168

optimum flow rates of 50-75 mL/h. This sorting

function not only demonstrates efficient separation

but also operates at flow rates that are easily

compatible with immunomagnetic sorting. These

promising results suggest that this approach can be

effectively integrated with additional microfluidic

functions, to achieve high-purity, high-recovery CTC

sorting.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge support staff from Nano

Lyon and ILM-Tech technological platforms. All the

staff of the CIRCAN team from the Hospices Civils

de Lyon is also gratefully acknowledged for their help

on biological expertise. The authors acknowledge

financial support from INSERM, for the PURECHIP

project, Cancer-PCSI, ITMO Cancer, and from the

doctoral school ED 160 EEA for the thesis grant of

Emma Dupont. This project, recently accredited by

Lyonbiopôle, also benefits from the newly granted

support of Cancéropôle CLARA, the Auvergne-

Rhône-Alpes Region, and Clermont Auvergne

Métropole, as part of the Proof of Concept program.

REFERENCES

Akbarnataj, K., Maleki, S., Rezaeian, M., Haki, M., &

Shamloo, A. (2023). Novel size-based design of spiral

microfluidic devices with elliptic configurations and

trapezoidal cross-section for ultra-fast isolation of

circulating tumor cells. Talenta.

Al-Halhouli, A., Al-Faqheri, W., Alhamarneh, B., Hecht,

L., & Dietzel, A. (2018). Spiral microchannels with

trapezoidal cross section fabricated by femtosecond

laser ablation in glass for the inertial separation of

microparticles. Micromachines, 9(4).

Amini, H., Wonhee, L., & Di Carlo, D. (2014). Inertial

microfluidic physics. Lab on a Chip, 14(15).

Bhagat, A. A., Kuntaegowdanahalli, S. S., & Papautsky, I.

(2008). Continuous particle separation in spiral

microchannels using dean flows and differential

migration. Lab Chip, 8, 1906–1914.

Bhagat, A. A., Kuntaegowdanahalli, S. S., Kaval, N.,

Seliskar, C. J., Papautsky, I., & e. (2010). Inertial

microfluidics for sheath-less high-throughput flow

cytometry. Biomedical Microdevices, 12, 187-195.

Castro-Giner, F., & Aceto, N. (2020). Tracking cancer

progression: from. Genome Medicine, 12(1).

CellSearch Circulating Tumor Cell. (2024, January 10).

Clinical application. (Menarini Silicon Biosystems,

Inc) Retrieved from https://www.cellsearchctc.com/

clinical-applications/mbc-clinical-trials-case-studies

Descamps, L., Le Roy, D., & Deman, A. L. (2022).

Microfluidic-Based Technologies for CTC Isolation: A

Review of 10 Years of Intense Efforts towards Liquid

Biopsy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences.

Descamps, L., Marie-Charlotte, A., Jordyn, H., Samir, M.,

Clément, A., David, B., . . . Deman, A.-L. (2021). Self-

Assembled Permanent Micro-Magnets in a Polymer-

Based. Cells.

Di Carlo, D. (2009). Inertial microfluidics. Lab on a Chip,

9(21).

Di Carlo, D., Irimia, D., Tompkins, R. G., & Toner, M.

(2007). Continuous inertial focusing, ordering, and

separation. PNAS, 104(48), 18892–18897.

Gao, W., Yuan, H., Jing, F., Wu, S., Zhou, H., Mao, H., . .

. Jia, C. (2017). Analysis of circulating tumor cells from

lung cancer patients with multiple biomarkers using

high-performance size-based microfluidic chip.

Oncotarget, 8, 12917-12928.

Guofeng Guan, Lidan Wu, Ali Asgar S. Bhagat, Zirui Li,

Peter C. Y. Chen, Shuzhe Chao, Chong Jin Ong &

Jongyoon Han. (2013). Spiral microchannel with

rectangular and trapezoidal cross-sections for size

based particle separation. Scientific Reports, 3, 1475.

Hou, H. W., Warkiani, M. E., Khoo, B. L., Li, Z. R., A, R.,

Tan, D. S.-W., . . . Lim, C. T. (2013). Isolation and

retrieval of circulating tumor. Scientific Reports, 3.

Joseph M. Martel and Mehmet Toner. (2013). Particle

focusing in curved microfluidic channels. Scientific

Reports, 3.

Krawczyk, N., Meier-Stiegen, F., Banys, M., Neubauer, H.,

Ruckhaeberle, E., & Fehm, T. (2014). Expression of

Stem Cell and Epithelial-Mesenchymal

TransitionMarkers in Circulating Tumor Cells of Breast

Cancer Patients. BioMed Research International

.

Li, Q., Wang, Y., Gao, W., Qian, G., Chen, X., & Liu, Y.

S. (2024). A microfluidic device for enhanced capture

and high activity release of heterogeneous CTCs from

whole blood. Talanta.

Macaraniag, C., Zhou, J., Li, J., Putzbach, W., Hay, N., &

Papautsky, I. (2023). Microfluidic isolation of breast

cancer circulating tumor. Electrophoresis, 1859-1867.

Man Lee, L., Klarmann, G. J., Haithcock, D. W., Wang, Y.,

Bhatt, H., Prabhakarpandian, B., . . . Lai, E. (2023).

Label-free Enrichment of Human Adipose-Derived

Stem Cells using a Continuous Microfluidic Sorting

Cascade. Lab on Chip.

Mazzitelli, C., Santini, D., Gianluca Corradini, A.,

Zamagni, C., Trerè, D., Montanaro, L., & Taffurelli, M.

(2023). Liquid Biopsy in the Management of Breast

Cancer Patients: Where Are We Now and Where Are

We Going. Diagnostics, 13, 1241.

Nian, M., Chen, B., He, M., & Hu, B. (2024). A Cascaded

Phase-Transfer Microfluidic Chip with Magnetic Probe

for High-Activity Sorting, Purification, Release, and

Detection of Circulating Tumor Cells. Analytical

Chemistry.

Nikolas H., S., Fischer, J. C., Niederacher, D., &

Terstappen, L. W. (2016). Challenges for CTC-based

liquid biopsies: Low CTC frequency and diagnostic

Sorting Circulating Tumor Cells: A Low Flow Microfluidic Pre-Enrichment Function for Improved Separation in Serial Two-Stage Sorting

Device

169

leukapheresis as a potential solution. Expert Review of

Molecular Diagnostics, 16(2), 147-164.

Qiao, Z., Xiangyu, T., Anqin, L., & Wenguang, Y. (2024).

Novel Isolating Approaches to Circulating Tumor Cell.

Micromachines.

Wu, L., Guan, G., Hou, H. W., Bhagat, A. A., & Han, J.

(2012). Separation of Leukocytes from Blood Using

Spiral Channel with. American Chemical Society,

9324-9331.

Xiang, N., Wang, J., Li, Q., Han, Y., Huang, D., & Ni, Z.

(2019). Precise Size-Based Cell Separation via the

Coupling of Inertial Microfluidics and Deterministic

Lateral Displacement. Analytical Chemistry, 91,

10328-10334.

Zhu, Z., Ren, H., Wu, D., Ni, Z., & Xiang, N. (2024). High-

throughput and simultaneous inertial separation of

tumor cells and clusters from malignant effusions using

spiral-contraction-expansion channels. Microsystems

and Nanoengineering.

BIODEVICES 2025 - 18th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

170