Comparison Between the Effects of Continuous and non-Continuous

Visual Feedback on Motor Learning While Playing a

Muscle-Controlled Serious Game

Julia Habenicht

1

and Elsa Andrea Kirchner

1,2

1

University of Duisburg-Essen, Bismarckstraße 81 47057 Duisburg, Germany

2

Robotics Innovation Center, German Research Center for Artificial Intelligence,

Robert-Hooke-Straße 1 28359 Bremen, Germany

Keywords: Muscle-Controlled Serious Game, Motor Learning, Visual Feedback, Electromyogram, Continuous Feedback.

Abstract: The guidance hypothesis suggests that continuous feedback during learning may lead to feedback dependency,

with errors decreasing when feedback is provided and increasing when it is removed. This study investigates

the effect of continuous (CVF) versus non-continuous visual feedback (NCVF) on motor learning using a

muscle- controlled serious game. Subjects played the game for three consecutive days, with each day

consisting of seven training sets and one learning control set without feedback. One group received CVF

during training, while the other received NCVF. To assess transferability, the results of the learning control

sets were compared between groups. Time to success during training decreased for CVF, and average time to

reach the longest correct time period in the learning control set was higher for CVF compared to NCVF. The

number of missed goals decreased for CVF, aligning with the expected positive impact of continuous feedback

during training. However, the results for the learning control sets were inconclusive. While CVF showed a

potential dependency on feedback, the decrease in missed goals indicates improved motor learning. More test

days and subjects are required to confirm the findings and draw definitive conclusions regarding the guidance

hypothesis.

1

INTRODUCTION

Learning a new motor task can be difficult, especially

the learning of fine motor movements can be

challenging. The guidance hypothesis predicts that

the guiding properties of extended feedback are

positive for motor learning when used to decrease

errors during the task but can also lead to a

dependency on this feedback (Winstein, Pohl, &

Lewthwaite, 1994, Fuchs, Knauer, & Friedrich, 2018).

Therefore, a highly directive form of feedback could

be detrimental to learning. Furthermore, the guidance

hypothesis expects that practicing with a high relative

frequency of reinforced feedback will have a negative

effect on learning. (Winstein, Pohl und Lewthwaite

1994).

There are still controversies about the guidance

hypothesis today (McKay, et al. 2022). Sülzenbrück

& Heuer conducted a study in which subjects had to

move a courser, receiving either continuous feedback

or terminal feedback. During the task, the group that

received continuous feedback achieved better results

for the end position of the cursor. After practicing

with one of the feedback methods, subjects had to

perform the movement without feedback. The group

with terminal visual feedback achieved better results

compared to the group receiving continuous visual

feedback. (Sülzenbrück und Heuer, 2011)

Another study of Marco-Ahulló et al. investigated

the effect of different visual feedback frequencies

during a balance task on performance of a post-test

without feedback. Results presented in this study

show that reduced feedback is more effective at

learning a postural task than continuous feedback.

(Marco- Ahulló, et al. 2024) An increased

performance in arm movements by using less feedback

compared to 100% feedback was shown in a study of

Suvillian, Kantak and Burtner as well.

On the other hand, a conducted study of Goodwin

achieved better results in stability while performing

a balance task after practicing with concurrent

feedback compared to less feedback (Goodwin 2019).

A study investigating the acceleration of shoulder

Habenicht, J. and Kirchner, E. A.

Comparison Between the Effects of Continuous and non-Continuous Visual Feedback on Motor Learning While Playing a Muscle-Controlled Serious Game.

DOI: 10.5220/0013171100003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 1, pages 899-906

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

899

flexions achieved equal or surpass results with

concurrent visual feedback compared to terminal

feedback (Yamamoto und Ohashi 2014). Results of

the study from Wulf, Shea and Matschiner provide

support for the notion that higher feedback

frequencies are beneficial for the learning of a

complex motor skill. Subjects had to perform a virtual

slalom skiing task. Their findings suggests that there

may be an interaction between task difficulty and

feedback frequency. (Wulf, Shea und Matschiner

1998)

The current state of the art shows, that there are still

controverses according continuous and non-

continuous visual feedback in motor learning.

Improving motor skills can be beneficial for

rehabilitation, sport, or daily living situations.

Therefore, the investigation of the different feedback

methods is important. For this reason, the aim of this

study is to investigate continuous and non-continuous

visual feedback on learning the precise control of

muscle activity with a muscle controlled serious game

in a training and a learning control scenario.

2

METHODS

2.1

Participants

In the experiment 12 healthy subjects (7 males and 5

females; average age 27 ±4) voluntarily participated.

All subjects were righthanded in accordance to the

Edinburgh handedness inventory (Oldfield 1971).

Subjects gave their written informed consent to the

experiment and were told that they were allowed to

stop the experiment at any time without any

consequences. Subjects were divided in two groups

consisting of six subjects each. One group received

continuous visual feedback and the other group

received non-continuous visual feedback. The group

selection was randomized.

2.2

Data Acquisition

The following descriptions of the serious game and

the experimental set-up is an adapted version of an

(Habenicht and Kirchner 2024). The difference

between the previous paper is non-continuous visual

feedback which was substituted with the before used

auditory feedback.

Electromyography (EMG)

For measuring muscle activity, subjects were

prepared with surface EMG electrodes before the

experiment started. A bipolar 16 channel EMG

system from Cometa was used. After skin

preparation, which included the cleaning with

alcohol, the electrodes were placed on the m. flexor

digitorum. The placement was based on the SENIAM

guidelines (Hermens, et al. 2000). to ensure that the

electrode is in the same position for each

measurement, the electrode position was documented

with photos.

2.2.1

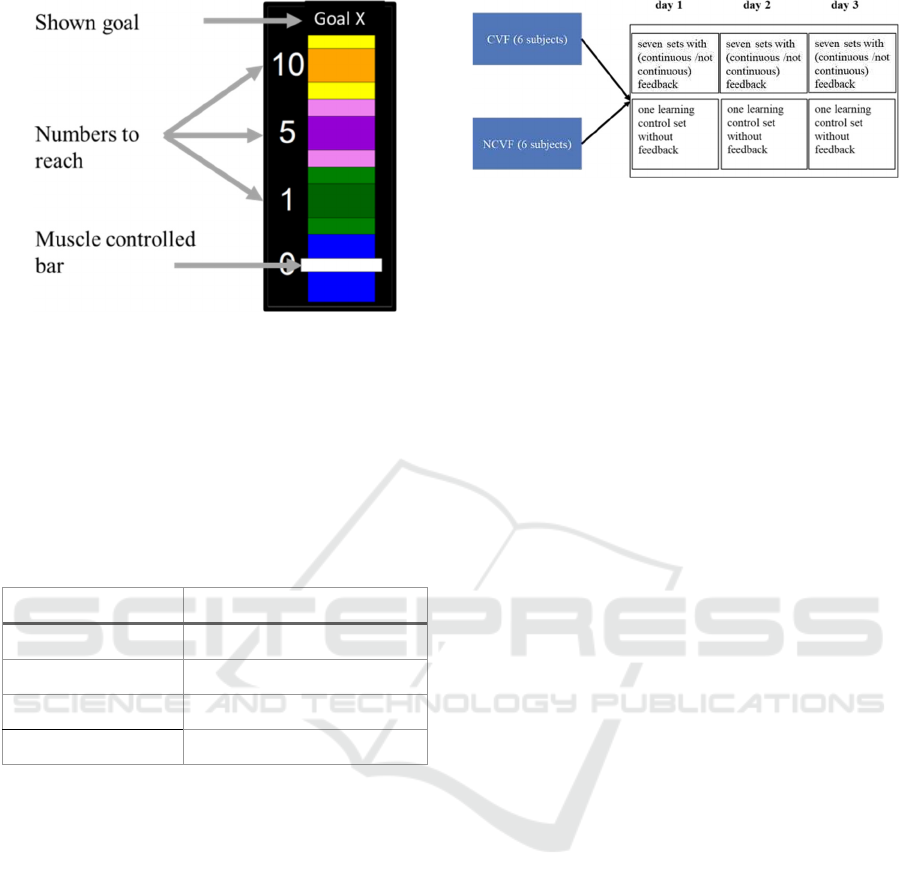

Serious Game

Serious games are games, which aren’t there just for

fun but also to have positive effects on the player

(Olgers, de Weg and Ter Maaten 2021). The serious

game consists of a column divided into four areas

(Figure 1). These areas can be reached by a bar,

which is controlled by the contraction of the m.

flexor digitorum muscle. this muscle was used

because it is considered easy to use. Since all

muscles are activated in the same way, it should be

possible to draw conclusions about the possible

behavior of the other muscles. Next to the areas the

digits 0,1,5, and 10 are shown. The aim of the game

is to reach the areas of the digit (1,5, and 10)

displayed in randomized order as accurately as

possible with the muscle-controlled bar. The digit to

be reached is clearly displayed above the column.

The bar must be in the range of the displayed digit

for at least three seconds. As soon as the bar is in the

correct range, a countdown of three seconds appears

After the three seconds in the goal area the bar must

be steered into the 0 range by relaxing the muscle.

After another three seconds in this area, the next digit

to be reached will be displayed. The next goal to

reach will only appear, when the one before was

successfully reached.

The group that receives continuous visual

feedback (CVF) can see the moving bar and its current

position all the time.

The group with non-continuous visual feedback

(NCVF) can only see the bar when it is in the correct

area of the column. When the bar is outside of the area

of the goal, it will not be displayed.

Before playing, the game had to be calibrated. We

used the maximum muscle activity. The average of a

five-second maximum muscle contraction (MVC)

was calculated. The areas of the column were defined

based on the average MVC value. The MVC value

represents 100%. A detailed description of which

number corresponds to which muscle activity relative

to MVC can be seen in Table 1.

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

900

Figure 1: Muscle-controlled serious game. The white bar is

controlled by muscle activity and moves when muscle

activity changes. The digits 1, 5 and 10 are the goals to

reach. These goals are shown above the column. When the

bar was steered in the correct goal area, a countdown of

three seconds appears. After holding the bar in the correct

range for three seconds, the muscle can be relaxed and the

next goal to reach is displayed.

Table 1: Goals with the corresponding muscle activity

calculated out of the maximal voluntary contraction

(MVC).

goals muscle activity

goal 0 0%-20% of MVC

goal 1 20%-40% of MVC

goal 5 40%-60% of MVC

goal 10 60%-80% of MVC

2.2.2

Experimental Set-up

Seven sets of the game were played for training with

a following learning control set each of the three days

in a row. In each set (training and learning control set)

every number had to be reached three times. The

order was randomized. The learning control set

consists of a set in which the subjects didn’t receive

any feedback of the game. It just showed the target

and the subjects had to contract the muscle the right

way out of their memory. After they assumed they

were in the right area for least three seconds without

feedback, they had to relax the muscle and the next

target was displayed. A detailed description of the

experimental design is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Description of the experimental setup. Subjects of

both groups played the game on three days in a row. Every

day consists of playing seven sets with one of the feedback

methods and one set of a learning control set without

feedback.

2.2.3

Data Processing

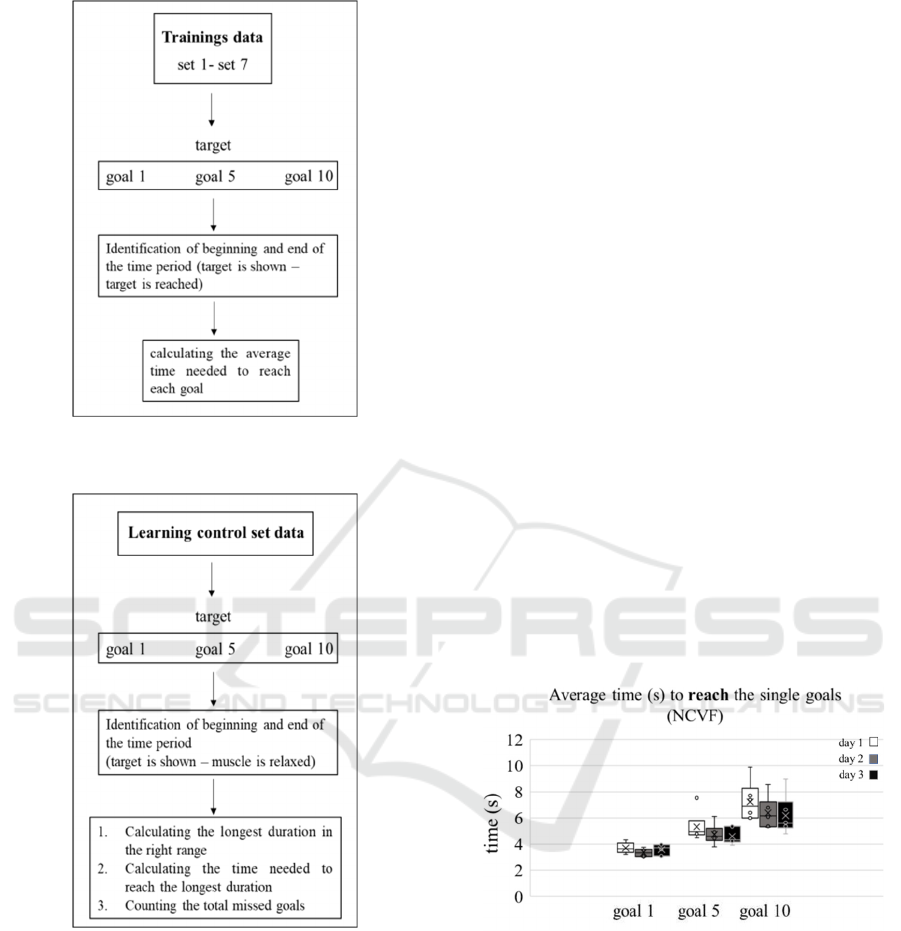

The analysis of the data is divided into two parts. The

analysis of the training set data and the analysis of the

learning control set data. The analyzed training set

data consists of the data collected from the moment

that the goal to reach was displayed till the moment

the goal was achieved. Out of these data the average

time taken by a subject to achieve each goal of the

training sets was determined. The time was calculated

over seven training sets for each goal on each day for

all subjects.

For the learning control sets, the period from the

moment that the goal was displayed until the muscle

was relaxed again (reached area “0”) was determined.

It was calculated for every goal on each day for all

subjects of each group. Subjects had to reach each

goal for three times. As no feedback was given during

the learning control set, subjects did not know

whether or when they achieved the goal. To evaluate

the success the average longest time period

(calculated out of three) that a subject spent

continuously in the respective goal areas was

determined for each day. The time needed to achieve

this longest continuous time period in the correct

range was determined. This was carried out for each

subject on each day for all goals

As the test subjects did not receive any feedback

in this sets, they may not have achieved the targets at

all. The total missed goals were calculated for each

subject of the groups as well.

For the analysis of the results of the training sets,

time needed to reach the goals was investigated. The

detection of motor learning in the learning control set

is counted as a decrease in missed goals. An increase

in time (s) spent in the correct area and a decrease in

time (s) to achieve the longest period of time spend in

the correct range will be also counted as a learning

effect.

Comparison Between the Effects of Continuous and non-Continuous Visual Feedback on Motor Learning While Playing a

Muscle-Controlled Serious Game

901

Figure 3: Description of the data processing of the training

set data. This process was applied every day’s data sets.

Figure 4: Description of the data processing of the learning

control set data. This process was applied on every learning

control set data.

2.3

Statistical Analysis

For the statistical analysis a two-sided independent,

not paired Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test was

performed. The data for the analysis consists of two

parts. First the average time needed to reach each goal

on each day was calculated. The test was performed

between the average time of the CVF group and the

NCVF group of each day individually. Second, the

average time needed to achieve the longest period of

time continuously spend in the correct range was also

analyzed. The test was performed between the

average time of the CVF group and the NCVF group

of each day individually. The significance value was

set to p< 0.05.

3

RESULTS

3.1

Results of the Training Sets

The following section consists of the analysis of the

time needed to reach the goals in the training sets. The

time is given in seconds.

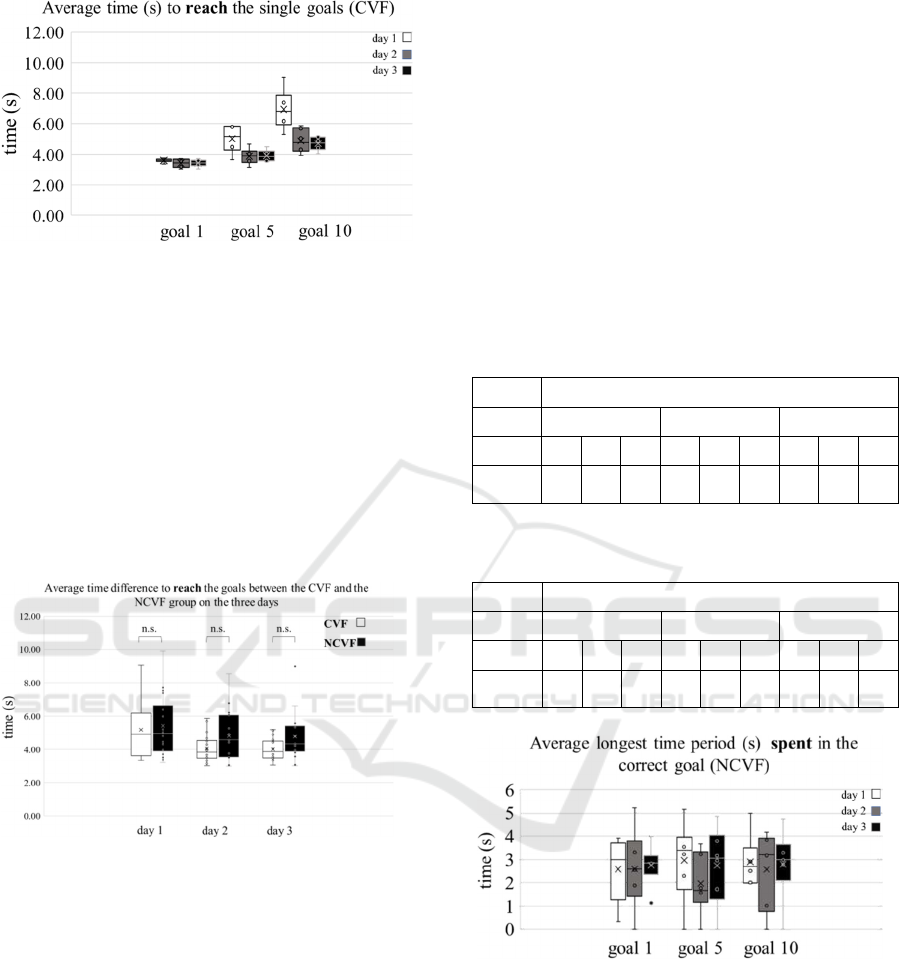

3.1.1

Analysis of the Time Needed to Reach

the Goal

Figure 5 depicts the comparison of the average time

(s) the NCVF group needed to succeed in each goal

between the training sets of the three days. The

average time to reach the single goals decreased for

goal 5 and goal 10 within the days. For goal 1 the time

was lowest on day 2 and highest on day 1 and day 3.

The highest time differences occurred between day 1

and day 2 in goal 10. The lowest differences were

found between the time differences of goal 1. Goal 1

was reached fastest on every day. Goal 10 was

reached slowest on every day.

Figure 5: Comparison of the average time (s) the NCVF

group needed to succeed in each goal between the training

sets of the three days.

Figure 6 depicts the comparison of the average time

(s) the CVF group needed to succeed in each goal

between the training sets of the three days. It can be

seen that the average time to reach the single goals

decreases for every goal over the days. The highest

time differences occurred between day 1 and day 2 in

goal 10. The lowest differences were found between

the time differences of goal 1. Goal 1 was reached

fastest on every day. Goal 10 was reached slowest on

every day.

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

902

Figure 6: Comparison of the average time (s) the CVF

group needed to succeed in each goal between the training

sets of the three days.

Figure 7 depicts the comparison of the average time

to reach the goals between the CVF group and the

NCVF group of the three days. Each Boxplot consist

of the average time for reaching the goals in the

training sets of each subject in the groups. The

average time for reaching the goals decreases for both

groups within the days. On day 2 and day 3 the needed

time for reaching the goals is less in the CVF group

compared to the times of the NCVF group. However,

these results are not significant.

Figure 7: Comparison of the average times needed to reach

the goals in the training sets between the CVF and the

NCVF groups on three days.

3.2

Results of the Learning Control Set

The following section consists of the analysis of the

total number of missed goals and the time needed to

reach the goals in the learning control sets. The time

is given in seconds.

3.2.1

Analysis of the Total Number of Missed

Goals

Subjects had to reach every goal three times in one

learning control set. Table 2 depicts the total number

of missed goals on every day in the NCVF group. For

goal 1 the number of missed goals does decrease from

five to zero within the three days. The missed goals

for goal 1 consist of three subjects. For goal 5 the

missed goals were five for day 1, seven on day 2 and

four on day 3 (5 subjects). The missed goals for goal

10 on day 1 was one, on day two it was five and four

on day 3 (3 subjects).

The total number of missed goals on every day of

the CVF group is depicted in Table 3. For goal 1 the

missed goals on day 1 were 0, on day 2 five and on

day 3 the number of missed goals was one (3

subjects). For goal 5 the missed goals on day 1 and

day 2 were two and on day 3 three. For goal 10 the

number of missed goals was one on every day.

Table 2: Total missed goals of the NCVF group in the

learning control sets of each day.

total missed goals NCVF group

Goal 1 Goal 5 Goal 10

day 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3

missed

goals

5 3 0 5 7 4 1 5 4

Table 3: Total missed goals of the CVF group in the

learning control sets of each day.

total missed goals CVF group

Goal 1 Goal 5 Goal 10

day 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3

missed

goals

0 5 1 2 2 3 1 1 1

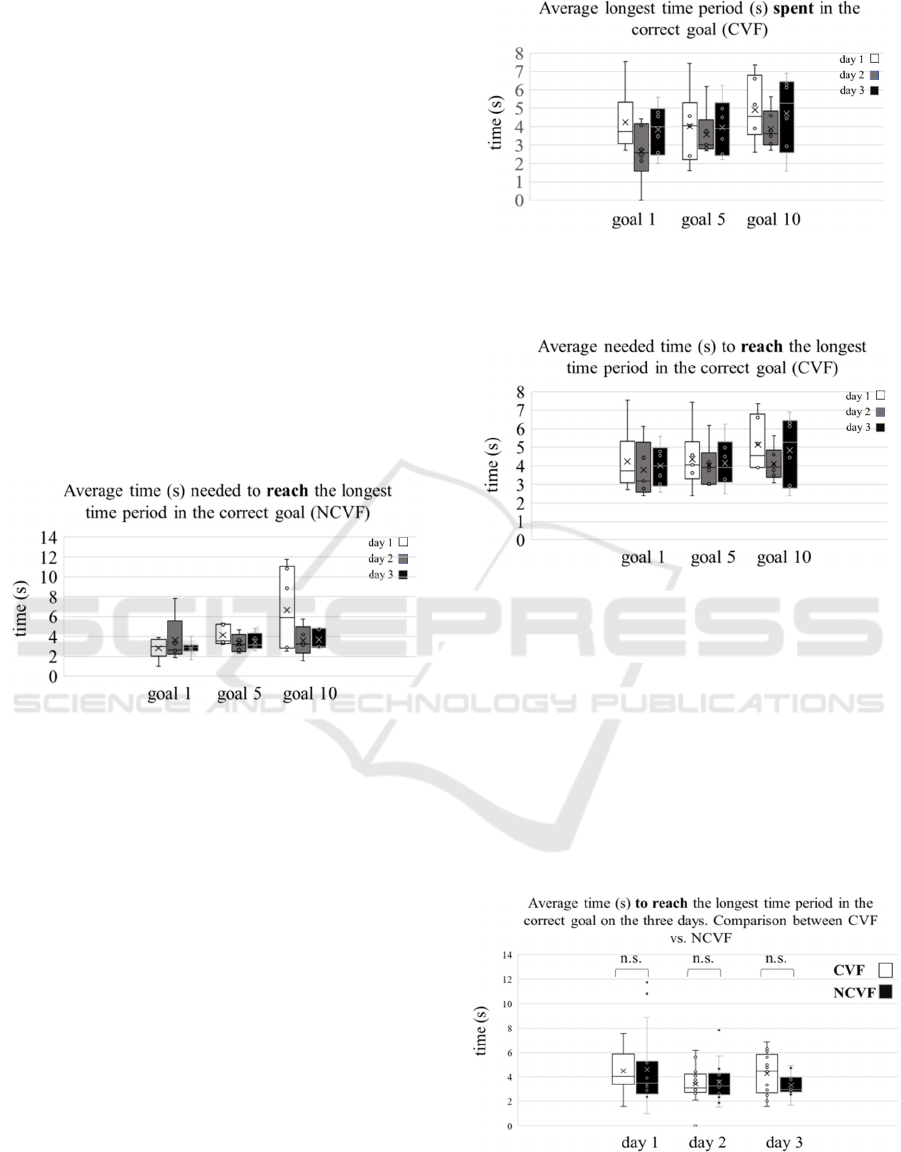

Figure 8: Comparison of the average longest period of time

(s) spent in the correct goal between the three days.

Depicted is the NCVF group in the learning control set.

3.2.2

Analysis of the Time (S) Needed to

Reach the Goal

As in the learning control set no feedback was given

on how many seconds were spent in the right range,

the longest duration spent in the right range was

calculated as well as the time needed to achieve the

longest time period spent in the correct goal.

Comparison Between the Effects of Continuous and non-Continuous Visual Feedback on Motor Learning While Playing a

Muscle-Controlled Serious Game

903

Figure 8 depicts the comparison of the average

longest period of time spent continuously in the

correct goal between the three days of the NCVF

group. For goal 1 and goal 5 the longest period of time

spent continuously in the right range was on day 1 and

the shortest on day 2. The median is around 3 seconds

on day 1 and day 3. For goal 10 the longest period of

time spent continuously in the correct range was

achieved on day 2 and the shortest on day 1. The

median is around 3 seconds on day 2 and day 3.

Figure 9 depicts the comparison of the average

time(s) needed to reach the correct goal between the

three days of the NCVF group. Longest time to reach

longest period of time spent continuously in the

correct goal was needed on day 1 for every goal. For

goal 1 the shortest time was needed on day 2. The

shortest time needed to reach the longest period of

time spent continuously in the correct range for goal

5 and goal 10 was on day 3. The time decreases for

every goal within the days.

Figure 9: Comparison between the average time (s) needed

to reach the longest time period in the correct goal between

the three days. Depicted is the NCVF group in the learning

control set.

Figure 10 depicts the comparison of the average

longest time period (s) spent continuously in the

correct goal between the three days of the CVF group.

For goal 1 and goal 10 the longest period of time spent

continuously in the right range was achieved on day

3 and the shortest on day 2. For goal 5 the longest

period of time spent continuously in the correct goal

was on day 1 and the shortest on day 2 as well. Apart

from goal 1 on the second day, the targets were

always held for at least three seconds on average.

Figure 11 depicts the average needed time to reach

the longest period of time spent continuously in the

correct goal for each goal on every day. For goal 1

and goal 10 the shortest time needed to reach the

longest period of time spent continuously in the

correct goal was achieved on day 2 and the longest

time was needed on day 3. For goal 5 the time slightly

decreases within the days.

Figure 10: Comparison of the average longest duration (s)

spent in the correct goal between the three days. Depicted

is the CVF group in the learning control set.

Figure 11: Comparison of the average time (s) needed to

reach the longest duration in the correct goal between the

three days. Depicted is the CVF group in the learning

control set.

Figure 12 depicts the comparison of the average time

needed to reach the longest period of time in the

correct goal between the CVF group and the NCVF

group of the three days. Each Boxplot combines the

data of all goals of each day.

The CVF group needed more time compared to

the NCVF group on day 1 and day 3. On day 2 both

groups are almost the same. However, the results are

not significant.

Figure 12: Comparison of the average time needed to reach

the longest period of time in the correct goal on each day

between the CVF group and the NCVF group in the

learning control set.

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

904

4

DISCUSSION

Both groups improved their average time to succeed in

reaching the goals in the training sets within the days.

However, the success in the training sets for the CVF

group was faster on average although the differences

are not significant. It seems that continuous visual

feedback helped reaching the goals faster although

differences were not significant. This criterion corres-

ponds more to a training effect than a learning effect.

Based on the results from the training sets, the

decrease in the time to reach the correct target could

lead to the assumption that there was an improvement

in the CVF compared to the NCVF.

However, if we now look at the results from the

learning control sets, this does not appear to be

transferable. Since a countdown of three seconds was

displayed in the training sets when the bar was in the

correct area, the sense of timing could be practiced.

Except of day 2, the CVF group spent on average

more than 3 seconds in the correct area. The NCVF

group spent on average very close to three seconds in

the correct range on all three days. This could lead to

the assumption that the CVF group was more

uncertain or more cautious in the execution of the task

which could be a sign of stronger dependency on

feedback. Moreover, the time required to reach the

longest period of continuous time spent at the correct

target decreased in the NCVF group. In the CVF

group, this time increased on the third day compared

to day 1. On the other hand, the number of missed

targets was lower in the CVF group than in the NCVF

group. While some criteria that were defined as motor

learning for the learning control sets were fulfilled by

both of the groups the observed results appear to be

controversial. One could assume that the CVF group

was more insecure in the learning control sets, which

is why they needed more time to reach the targets and

stayed longer in the targets to make sure they had

reached them long enough. Nevertheless, fewer goals

were missed in the CVF group. The observed

improvement in the time to achieve the goals in the

learning control sets for the NCVF group as well as

the more exact duration in the correct goal compared

to the CVF group is consistent with results from

previous studies, which showed that a greater learning

effect occurs with non-continuous feedback

compared to continuous feedback (Marco- Ahulló, et

al. 2024; Sullivan, Kantak und Burtner 2008;

Sülzenbrück und Heuer, 2011).

Nevertheless, the results of our study must be

interpreted with caution, as our results are not

significant and some are controverse. To be able to

make a clear statement regarding the guidance

hypothesis, it would be useful to carry out more than

three training days and more test subjects to see

whether more of the defined criteria for motor

learning are fulfilled and whether the found

differences prove to become significant with a larger

number of subjects.

5

CONCLUSION

Both groups fulfill predefined criteria for motor

learning, even though the results are not statistically

significant. Since some of the results are

controversial, extending the investigation to more

than three test days and including additional subjects

would be beneficial in order to provide a clearer

statement regarding the guidance hypothesis.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The studies involving human participants were

approved by the local Ethical Committee of the

University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany. The

participants provided their written informed consent

to participate in this study.

REFERENCES

Fuchs, Dominik, Martin Knauer, and Petra Friedrich.

„Chancen von akustischem Feedback für die

motorische Rehabilitation am Beispiel.“ DAGA.

München, 2018.

Goodwin, Jeff E. "Scheduling Concurrent Visual Feedback

in Learning a Continuous Balance Task." Journal of

Motor Learning a Development, 2019.

Habenicht, Julia, and Elsa Andrea Kirchner. „Preliminary

Results on the Evaluation of Different Feedback

Methods for the Operation of a Muscle-Controlled

Serious Game.“ 17th International Conference on Bio-

inspired Systems and Signal Processing. Rom, 2024.

Hermens, H J, B Freriks, C Disselhorst-Klug, and G Rau.

„Development of recommendations for SEMG sensors

and sensor placement procedure.“ Journal of

Electromyography and Kinesiology, October 2000.

Marco-Ahulló, Adria, Israel Villarrasa-Sapiña, Jorge

Romero-Martínez, Gonzalo Monfort-Torres, Jose Luis

Toca-Herrera, und Xavier García-Massó. „Effect of

Reduced Feedback Frequencies on Motor Learning in a

Postural Control Task in Young Adults.“ Sensors,

2024.

MathWorks.. https://de.mathworks.com/help/dsp/ug/sliding-

window-method-and-exponential-weighting-method.ht

ml (Last access: March 2024).

Comparison Between the Effects of Continuous and non-Continuous Visual Feedback on Motor Learning While Playing a

Muscle-Controlled Serious Game

905

McKay, Brad, Julia Hussien, Mary-Anne Vinh, Alexandre

Mir-Orefice, Hugh Brook, and Diane M Ste-Marie.

„Meta-analysis of the reduced relative feedback

frequency effect on motor learning and performance.“

Psychology of Sport and Exercise, July 2022.

Oldfield, R C. "The assessment and analysis of handedness:

the Edinburgh inventory." Neuropsychologie, March

1971.

Olgers, T. J., de Weg, A. A., & Ter Maaten, J. C. (2021,

January 25). Serious Games for Improving Technical

Skills in Medicine: Scoping Review. JMIR Serious

Games.

Ranganathan, Vinoth K, Vlodek Siemionow, Jing Z Liu,

Vinod Sahgal, and Guang H Yue. „From mental power

tu muscle power-gaining strength by using mind.“

Neuropsychologia, 2004.

Sullivan, Katherine J, Shailesh S Kantak, and Patricia A

Burtner. „Motor learning in children: feedback effects on

skill acquisition .“ Physical Therapy, June 2008: 720-

732.

Sülzenbrück, Sandra. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 2012.

Sülzenbrück, Sandra, and Herbert Heuer. „Type of visual

feedback during practice influences the precision of the

acquired internal model of a complex visuo-motor

transformation .“ Ergonomics, January 2011.

Thongpanja, Sirinee, et al. „Effects of Window Size and

Contraction Types on the Stationarity of Biceps Brachii

Muscle EMG Signals.“ INRIA.HAL.SCIENCE, 2014.

Uma, B. V., M. Vishnu Priya, P. Harshita, and K.N. Maruthy.

"Assessment of Hand Grip Strength & Fine Motor Skills

in Skilled & Non Skilled Persons." International Journal

pf Physiology, 2019.

Winstein, C J, P S Pohl, und R Lewthwaite. „Effects of

physical guidance and knoledge of results on motor

learning: support for the guidance hypothesis.“ Research

quarterly for exercise and sport, December 1994.

Wulf, G, C H Shea, and S Matschiner. „Frequent feedback

enhances complex motor skill learning .“ Journal of

Motor Behavior, June 1998.

Yamamoto, Ryohei, and Yukari Ohashi. „The Effects of

Inaccessible Visual Feedback Used Concurrently or

Terminally.“ Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 2014:

731-735.

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

906