Privacy Policies in Medium-Sized European Town Administrations: A

Comparative Analysis of English and German-Speaking Countries

Henry Hosseini

1,2 a

1

Department of Information Systems, University of Münster, Münster, Germany

2

Institut for Internet Security, Westphalian University of Applied Sciences, Gelsenkirchen, Germany

Keywords:

GDPR, Privacy Policies, Medium-Sized Towns.

Abstract:

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has been in force since May 2018. Organizations and indi-

viduals must comply with this legislation if they collect or process the personal information of residents of the

European Union. Prior research has focused on the examination of the privacy policies of the most frequently

visited websites or mobile applications with the highest number of installations. The present study assesses the

privacy policies of a less explored field: medium-sized town administrations. For this purpose, we analyzed

and evaluated 644 privacy policies collected in Austria, Germany, and Ireland, focusing on their coverage of

different data practice categories and GDPR-related dictionary phrases. We employed semi-automated data

collection methods, deep learning and NLP techniques, and manual labor to perform this analysis. Our find-

ings provide insight into the privacy policy landscape of medium-sized town administrations, where Austria

and Germany exhibit a higher average coverage of GDPR data practice categories than Ireland.

1 INTRODUCTION

One of the key advantages of a digitized society is

the enhanced availability and diversity of digital ser-

vices, which benefit both individuals and organiza-

tions. Digital technologies are transforming how in-

dividuals interact with and influence society (Lanks-

hear and Knobel, 2008; Reis et al., 2018). The vision

of the European Union (EU) for the digital transfor-

mation of cities encompasses enhanced access to e-

government, e-health, digital skills, e-competences,

and other public administration services (European

Commission, 2023b). The operation of these services

often necessitates the collection of citizens’ personal

data, which must be processed and stored in a respon-

sible and secure manner. To address these concerns

and ensure transparency, the General Data Protection

Regulation (GDPR) was enforced in May 2018 and

applies to providers that collect, store, or process the

personal data of EU residents.

The GDPR is designed to empower individuals

with greater control over their personal data while

imposing rigorous requirements on organizations that

collect, store, process, or share the personal data of

EU residents. In the event of non-compliance with

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9691-0329

the regulations, entities may be subject to substan-

tial financial penalties. Previous research has iden-

tified the five most frequent violations that have re-

sulted in sanctions, with the unlawful processing and

disclosure of personal data being the most frequent

violation, followed by failures in upholding and safe-

guarding data subject rights and individuals’ personal

information, as well as inadequate cooperation with

supervisory authorities (Presthus and Sønslien, 2021).

Recently, five municipalities in Iceland were fined for

non-compliance with general data processing princi-

ples (European Data Protection Board, 2023).

With respect to informing affected individuals,

particularly end-users of public administration web-

sites, privacy policies serve as the primary means

of informing users about the collection and process-

ing of their personal data and associated user rights.

These policies should provide affected individuals

with transparent information on their rights described

in Articles 13 to 22 of the GDPR regarding their col-

lected and processed personal data, including, but not

limited to, data erasure, rectification, access, etc.

Considering cities in the context of digitaliza-

tion, there is a notable discrepancy in the accessi-

bility, adoption, and utilization of digital technolo-

gies between urban and rural areas. This imbalance

can be attributed to various factors, including insuf-

60

Hosseini, H.

Privacy Policies in Medium-Sized European Town Administrations: A Comparative Analysis of English and German-Speaking Countries.

DOI: 10.5220/0013171800003899

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2025) - Volume 2, pages 60-71

ISBN: 978-989-758-735-1; ISSN: 2184-4356

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

ficient bandwidth in rural regions, which are less ap-

pealing to information and communication technol-

ogy (ICT) providers due to low profitability (Holl-

man et al., 2021; Stern et al., 2009). As many peo-

ple relocate to metropolises seeking economic oppor-

tunities and a higher quality of life, the proportion

of individuals residing in urban areas has increased

from 37 % to 48 % (OECD and European Commis-

sion, 2020). This discrepancy arises primarily be-

cause larger cities generally have more resources, in-

vestments, and stakeholders compared to medium-

sized towns, which are expected to provide the same

quality of services to their citizens (OECD and Eu-

ropean Commission, 2020). Furthermore, previous

research has indicated that the majority of research

is concentrated on densely populated areas, with less

attention directed towards rural regions and smaller

towns (Hosseini et al., 2018).

Our research aims to outline the current landscape

of privacy policies offered to citizens by the adminis-

trations of medium-sized European towns. Given the

linguistic diversity in Europe, we restrict the scope of

our investigation to three European countries: Aus-

tria, Germany, and Ireland. We selected these coun-

tries because English and German are the two most

commonly spoken languages in Europe (Directorate-

General for Communication, 2014), affecting many

EU residents. Additionally, our proficiency in both

languages facilitates the analysis and assessment of

the texts in the privacy policies. Recent research has

highlighted the lack of studies in security and pri-

vacy venues that analyze privacy policies in languages

other than English (Mhaidli et al., 2023).

Given the aforementioned motivational facts, our

research question is formulated as follows:

RQ. How do the privacy policies of medium-

sized town administrations in English and German-

speaking European countries compare in terms of

aligning with the requirements of the GDPR?

The paper at hand is structured as follows: A re-

view of the related work is presented in the next sec-

tion. Section 3 describes the method employed to

construct our dataset, detailing the criteria and pro-

cess involved in selecting the towns that were in-

cluded in our analysis and the collection of their pri-

vacy policies. Section 4 outlines our research ap-

proach utilized to assess the alignment of the privacy

policies with GDPR stipulations. The results of ap-

plying this method are presented in Section 5. Section

6 discusses the findings and the current state of pri-

vacy policies in medium-sized town administrations

within the scope of this study, followed by proposing

recommendations and ideas for future research. Fi-

nally, Section 7 concludes this work.

2 RELATED WORK

In order to assess the impact of the GDPR enact-

ment, (Degeling et al., 2019) measured changes in

privacy policies before and after the GDPR enforce-

ment on the 500 most visited websites across 28 Eu-

ropean countries in 2018. They observed that the

number of websites that adopted privacy policies and

the length of the text of existing privacy policies had

increased. The study also assessed the presence of

GDPR-specific terms in the policies using a multilin-

gual dictionary created for this purpose. The authors

reported an increase in the usage of GDPR-specific

terminology, while some websites lacked any privacy

policy after the GDPR enforcement. (Hosseini et al.,

2024) confirmed this increase in the occurrence of

GDPR-specific terminology using keyness analysis.

(Wilkerson and Smith, 2023) examined the pri-

vacy challenges in smart cities, investigating the ex-

tent to which digital consumers are aware of the

privacy implications while navigating these environ-

ments. They conducted a comprehensive literature

review based on the theoretical frameworks of infor-

mation flow, social contracts, and the concept of be-

ing left alone. Additionally, they evaluated 30 fed-

eral and state government English privacy policies in

the United States (US), assessing their alignment with

these theoretical perspectives. The findings indicated

that some state governments may not fully comply

with federal privacy standards and that digital con-

sumers remain unaware of the privacy implications

associated with smart cities.

The most similar study to ours was a manual quan-

titative analysis of the privacy policies of Portuguese

municipalities (Dias et al., 2013). In 2013, this study

observed that only 4 % of Portuguese municipalities

disclosed the types of personal information collected

in their privacy policies. Our research differs from

this study in that, to the best of our knowledge, no

recent studies have focused on the analysis of the pri-

vacy policies of medium-sized town administrations

in Europe, particularly after the enforcement of the

GDPR. We believe that our study provides a founda-

tion for further research, as the protection of collected

and processed personal data is crucial in the field of

cybersecurity. Furthermore, it plays a significant role

in enhancing the trust of citizens in digitalization ef-

forts in medium-sized towns (Lai and Cole, 2022).

3 CORPUS CONSTRUCTION

This section outlines the research method employed

to construct a dataset of medium-sized towns in Aus-

Privacy Policies in Medium-Sized European Town Administrations: A Comparative Analysis of English and German-Speaking Countries

61

tria, Germany, and Ireland, and to collect the privacy

policies from the websites of these towns’ adminis-

trations. We present our method for evaluating the

privacy policies of these websites and assessing their

alignment with the requirements of the GDPR. These

steps are illustrated in Figure 1.

• Medium-sized town Identification

• Privacy policy collection

• Privacy policy preprocessing

Corpus Construction

• Data practice classification

• Dictionary analysis

• Coverage analysis

Corpus Analysis

Figure 1: Overview of the research method.

3.1 Identification of Medium-Sized

Towns

To characterize medium-sized towns, we adopt the

definition provided by the Federal Institute for Re-

search on Building, Urban Affairs, and Spatial Devel-

opment of Germany for municipality types. Accord-

ing to this definition, small towns are characterized by

a population of 5,000 to 20,000 inhabitants, medium-

sized towns exhibit a population of 20,000 to 100,000

inhabitants, and large cities are distinguished by a

population of at least 100,000 inhabitants (Milbert

and Porsche, 2022). We recognize that this definition

may not be universally applicable across the countries

included in our study and may be subject to variation

based on geographic and political contexts. Neverthe-

less, this approach allows us to maintain consistency

among the towns under analysis, ensuring the compa-

rability of results. Thus, we employ this definition to

identify medium-sized towns that have a comparable

population range in Ireland and Austria.

The lists of medium-sized towns in Australia,

Germany, and Ireland were compiled using a semi-

automatic method that combined a web scraper with

manual labor. Wikipedia and the official census data

published by the respective governments served as the

primary data sources. The Wikipedia articles for each

town include the Uniform Resource Locators (URLs)

of the towns’ administrative websites.

To compile a list of medium-sized towns for

each country, we identified towns with populations

ranging from 20,000 to 100,000 inhabitants, utiliz-

ing Wikipedia’s city lists pertinent to the countries

in question. Subsequently, we added or removed

towns based on the countries’ most recent census

data (Central Statistics Office Republic of Ireland,

2021; Statisik Austria, 2023; Wikipedia, 2023).

The following attributes were automatically col-

lected for each town: name, state/county, popula-

tion, and URL. The web scraper used for this pur-

pose was constructed using the Python library Re-

quests (Python Software Foundation, 2023) to per-

form HTML requests and Parsel (Scrapy project,

2023) for parsing HTML responses. The data col-

lected was manually reviewed, during which any

missing URLs and errors were corrected. The final

town dataset encompasses 21 Austrian, 603 German,

and 20 Irish medium-sized towns. The structure of

this dataset is depicted in Tables 1, 2, and 3.

3.2 Privacy Policy Collection

The next step involved collecting the privacy policies

from the town administration websites. These poli-

cies are essential for the assessment of data practices

and data subject rights. However, in contrast to app

stores, where each application provides a link to its

respective privacy policy, website privacy policies are

not easily accessible in a unified manner.

To address this challenge, (Hosseini et al., 2021)

developed an open-source toolchain that employs ex-

amined best practices to automatically (a) detect and

collect potential privacy policies from websites in 42

European and non-European languages, and (b) pre-

process them in multiple steps, including text ex-

traction, language detection, and filtering non-privacy

policies using trained machine learning classifiers.

Moreover, the unification of the data preparation can

enhance research comparability and reveal common

analysis pitfalls.

We leveraged this comprehensive toolchain to

download potential privacy policies from the towns’

websites during the period from June to October

2023. The privacy policy detection module accessed

the landing page of each town’s website using a head-

less Firefox browser session via the Selenium Web-

Driver API (Selenium, 2023), which retrieves the

HTML document. The document is then parsed with

Beautiful Soup to identify all URLs. Each URL,

along with its preceding HTML element and link text,

is matched against a predefined multilingual word list

created by (Degeling et al., 2019), which contains

terms that may potentially point to URLs of privacy

policies. These URLs are subsequently visited auto-

matically, and the corresponding web pages or PDF

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

62

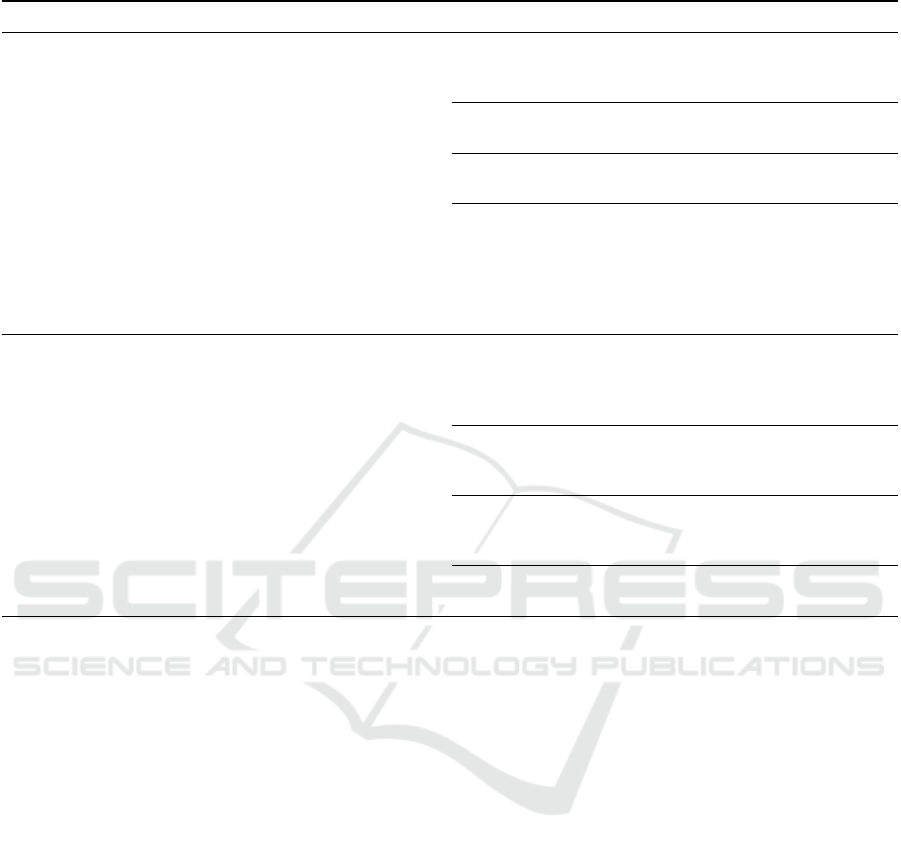

Table 1: Sample entries of the Austrian town dataset (N=21).

Town State Population URL

Villach Carinthia 64,071 https://www.villach.at/

Wels Upper Austria 63,181 https://www.wels.gv.at/

Sankt Pölten Lower Austria 56,360 https://www.st-poelten.at/

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Hallein Salzburg 21,353 https://www.hallein.gv.at/

Schwechat Lower Austria 20,763 https://www.schwechat.gv.at/

Mödling Lower Austria 20,531 http://www.moedling.at/

Table 2: Sample entries of the German town dataset (N=603).

Town State Population URL

Kaiserslautern Rhineland-Palatinate 99,794 https://www.kaiserslautern.de

Iserlohn North Rhine-Westphalia 98,865 https://www.iserlohn.de/

Gütersloh North Rhine-Westphalia 95,459 http://www.guetersloh.de/

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Friesoythe Lower Saxony 20,064 https://www.friesoythe.de/

Eschborn Hesse 20,015 http://www.eschborn.de/

Enger North Rhine-Westphalia 20,007 http://www.enger.de

Table 3: Sample entries of the Ireland town dataset (N=20).

Town State Population URL

Limerick City Limerick 94,192 https://www.limerick.ie/

Galway City Galway 79,934 https://www.galwaycity.ie/

Waterford City Waterford 53,504 http://www.waterfordcouncil.ie/

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Mullingar Westmeath 20,928 https://www.mullingar.ie/

Celbridge Kildare 20,288 http://celbridge.ie/

Wexford Wexford 20,188 http://www.wexford.ie/

documents containing potential privacy policies are

retrieved and stored.

In October 2024, we revisited a subset of the pri-

vacy policies that were identified in 2023 as not meet-

ing the GDPR requirements, with the aim of assessing

their present state.

3.3 Privacy Policy Preprocessing

We utilized the privacy policy preprocessing module

of the aforementioned toolchain by (Hosseini et al.,

2021) to extract the plain text from the retrieved web

pages and PDF documents. According to the authors,

the Boilerpipe library with the NumWordRulesExtrac-

tor algorithm (Kohlschütter et al., 2010) performed

best in their tests for extracting text from collected

privacy policy webpages across the ten most common

European languages. We also tested the other text ex-

tractors included in this toolchain (CanolaExtractor

and Readability.js (Mozilla, 2023)) and made simi-

lar observations during our manual checks. There-

fore, we used the plain text extracted via the NumWor-

dRulesExtractor algorithm for the subsequent steps.

The preprocessing module also performs lemmati-

zation, a linguistic process that reduces words to their

base or canonical forms, known as lemmas, taking

into account the grammatical context, part of speech,

and linguistic features. For example, the lemma of

running is run, the lemma of better is good, or the

lemma of children is child.

The toolchain also incorporates a language detec-

tion ensemble that identifies the language of each text.

Additionally, it employs text classifiers to differenti-

ate between privacy policies and non-privacy policies.

These classifiers achieved accuracy scores of 99.1 %

for English and 99.6 % for German, respectively.

We reviewed the output and excluded documents

that were outside the scope of this study. Examples

of such documents include the privacy policies of

third-party websites, such as Google and Facebook,

which appeared as links on some landing pages dur-

ing the collection of privacy policies. Furthermore,

some websites contained dedicated privacy policies

for town administration departments that were unre-

lated to the main town administration’s website. The

resulting plain texts of the websites’ privacy policies,

after undergoing lemmatization and alongside their

metadata, formed the corpus subject to the analysis

described in the following section.

Privacy Policies in Medium-Sized European Town Administrations: A Comparative Analysis of English and German-Speaking Countries

63

4 CORPUS ANALYSIS

This section outlines the steps taken to derive in-

sights from the corpus constructed in the previous

section. We employed a combination of quantitative

dictionary-based methods and modern deep learning

techniques to gain these insights, as well as a qualita-

tive examination of privacy policies. In the following,

we describe these methods in detail.

4.1 Data Practices Classification

Our research made use of fine-tuned instances of the

BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from

Transformers) language model (Devlin et al., 2018).

These models were fine-tuned using the annotated

bilingual corpus of mobile application privacy poli-

cies (MAPP), which contains 64 English and 91

German manually annotated privacy policies (Arora

et al., 2022). The annotation scheme is based on

the OPP-115 English privacy policy corpus (Wilson

et al., 2016) and was refined to incorporate regula-

tory changes resulting from the enforcement of the

EU’s GDPR (and California’s CCPA/CPRA). The au-

thors report that the models achieved F1 scores rang-

ing from 60 % to 85 % for English and from 54 % to

74 % for German. These scores are typical for BERT-

based models used for the classification of data prac-

tices in privacy policies (cf. (Adhikari et al., 2023)).

We used these models to identify seven categories

of data practices and their attributes: (1) first-party

collection and use, (2) third-party collection and use,

(3) information type, (4) purpose of data collection,

(5) collection process, (6) legal basis for processing,

and (7) third-party entities. Table 4 presents a detailed

description of these categories and their attributes.

We report on the coverage of the data practice cat-

egories, i. e., the extent to which they are present or

absent in a privacy policy, in Section 5.

4.2 Dictionary-Based Approach

In addition to the previously described text classi-

fication approach, we employed a dictionary-based

method to examine the alignment of the privacy poli-

cies with the GDPR requirements. For this purpose,

we used the dictionary developed by (Degeling et al.,

2019), which encompasses GDPR-specific terms in

24 official European languages. This dictionary was

used to measure changes in privacy policies following

the enforcement of the GDPR in May 2018.

1

Native

1

The complete dictionary is provided in the Appendix

of the extended version of their conference paper, accessible

at https://arxiv.org/abs/1808.05096.

speakers validated the dictionary for 17 languages re-

garding correctness and sensitivity. We used the Ger-

man and English phrases from this dictionary, both of

which were validated by native speakers.

To conduct the dictionary-based analysis, we low-

ercased and lemmatized the dictionary phrases using

Spacy (Montani et al., 2020). We subsequently mea-

sured the coverage of the phrases within the lemma-

tized privacy policies.

We searched for the following English phrases

in the privacy policies of the Irish towns: data

protection officer, legitimate interest, rectification,

erasure, data portability, and supervising author-

ity. The equivalent German dictionary phrases were

searched in the privacy policies of German and

Austrian town administrations, specifically: Daten-

schutzbeauftragte, berechtigte Interessen, Berichti-

gung, Löschung, Datenübertragbarkeit, and Auf-

sichtsbehörde.

The rationale for selecting these phrases is rooted

in the requirements outlined in the GDPR. The pres-

ence of a “data protection officer” is necessary if (a)

public authorities process personal data, (b) personal

data are processed systematically on a large scale, or

(c) special categories of data (such as racial or ethnic

origin, genetic and biometric data, . . . ) are processed

by an entity (see Article 37(1) of the GDPR). A data

protection officer serves as a liaison between a data

controller and the supervisory authority and should

be accessible to data subjects for complaints. Articles

13(2)(d) and 14(2)(e) of the GDPR state that when

personal data is collected directly or indirectly (via

third parties) from a data subject, the data controller

must inform the data subject of their right to lodge a

complaint with the supervisory authority.

Considering “legitimate interest” as a legal ba-

sis for data collection requires balancing the inter-

ests of the data controller, i. e., the entity that col-

lects personal data, with those of the data subject, i. e.,

the individual whose personal data is being collected.

These interests must be justifiable, such as preventing

fraud and cyberattacks (Voigt and von dem Bussche,

2017). However, the use of this legal basis for data

processing has been the subject of past and recent re-

search on deceptive design and potentially question-

able data practices (Kamara and De Hert, 2018; Kyi

et al., 2023; Hosseini et al., 2024).

The phrases “rectification,”“erasure,” and “porta-

bility” are derived from the user rights specified in

Articles 16, 17, and 20 of the GDPR concerning col-

lected personal data (Helfrich, 2023).

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

64

Table 4: Applied taxonomy to identify data practices in the privacy policies (Arora et al., 2022).

Category Category Description Attribute Attribute Description

First-Party Collection/Use Privacy practices that describe

data collection or data use by the

company/organization owning

the website or mobile app.

Information Type What category of information is

collected or tracked by the com-

pany/organization?

Purpose What is the purpose of collecting

or using user information?

Collection Process How does the first party collect,

track, or obtain user information?

Legal Basis for Processing The GDPR prohibits the collec-

tion and processing of personal

data without a proper legal basis.

Therefore, every category of per-

sonal data requires the legal basis

to be clear and specific.

Third-Party Collection/Use Privacy practices that describe

data sharing with third parties or

data collection by third parties.

A third party is a

company/organization other than

the first-party

company/organization that owns

the website or mobile app.

Information Type What category of information is

shared with, collected by, or

otherwise obtained by the third

party?

Purpose What is the purpose of a third

party receiving or collecting user

information?

Collection Process How does the third party receive,

collect, track, or see user infor-

mation?

Third-party Entity The third parties involved in the

data practice.

4.3 GDPR Coverage Evaluation

The examination of the privacy policies for their

alignment with GDPR requirements, as outlined in

Section 4.1 and Section 4.2, encompasses 13 ele-

ments: two data practice categories, five data prac-

tice attributes, and six dictionary phrases. We as-

sess each privacy policy for the presence or absence

of these elements and report our findings, comparing

them across countries.

It is not our intention to assign scores based on

the degree to which these elements are covered, as not

all policies may require the inclusion of all elements.

To illustrate, the collection and processing of personal

data by third parties or the sharing of data with third

parties may not be conducted on the website of a town

administration. Consequently, there is no requirement

to include related data practice disclosures.

5 RESULTS

In this section, we present the results of our analysis

of the privacy policy corpus using the method outlined

in Section 4. We provide the findings at the country

level and discuss the implications of these results.

5.1 First Assessment in 2023

We conducted our first assessment of the privacy poli-

cies collected from the town administration websites

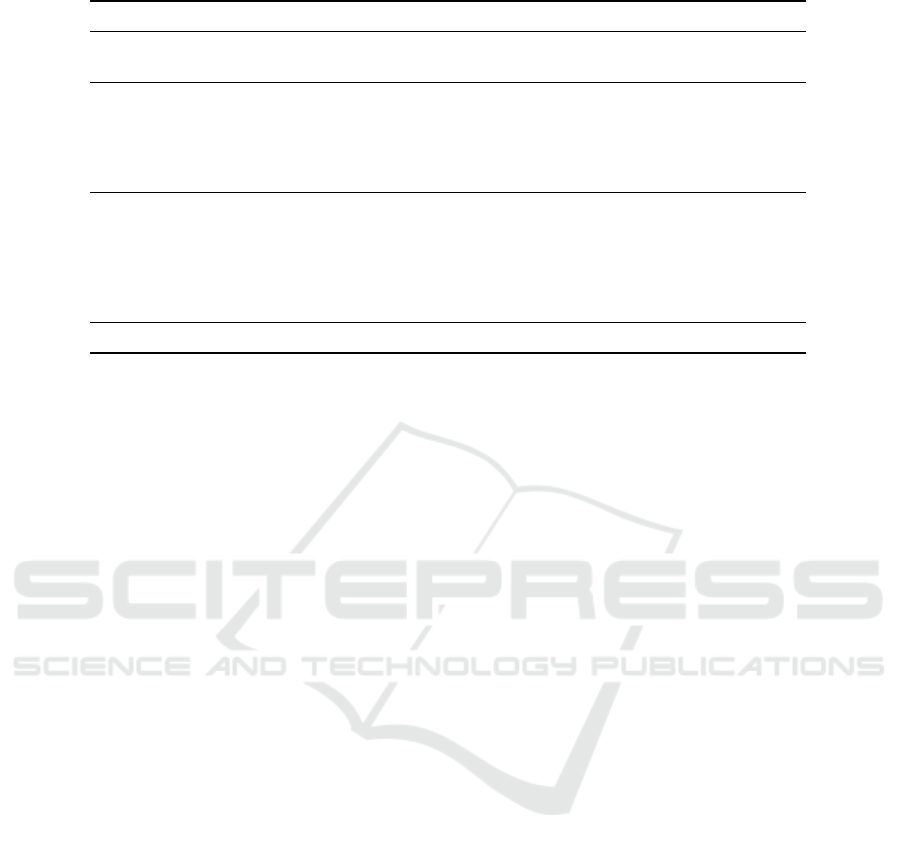

in 2023. In Table 5, each number indicates the overall

coverage (presence or absence) of the categories, at-

tributes, and dictionary phrases in the privacy policies

from each respective country, as well as the percent-

age of policies that incorporated them.

Upon examining the results, we observe similari-

ties among the three countries regarding relative cov-

erage. Regarding data practice categories, the privacy

policies of the three countries contained more disclo-

sures related to the collection or use of personal data

by first parties (Article 13 of the GDPR) than by third

parties (Article 14 of the GDPR). This observation in-

dicates that there are more statements describing data

use and collection by town administrations than there

are statements describing how data is shared with or

collected by third parties.

Concerning attributes, we observe that the privacy

policies collected in Germany address the types of in-

Privacy Policies in Medium-Sized European Town Administrations: A Comparative Analysis of English and German-Speaking Countries

65

Table 5: Coverage of data disclosures and phrases across countries.

Austria Germany Ireland

Category First Party 21 (100 %) 598 (99.2 %) 18 (90 %)

Third Party 20 (95.2 %) 571 (94.7 %) 14 (70 %)

Attribute Information Type 21 (100 %) 595 (98.7 %) 20 (100 %)

Purpose 21 (100 %) 592 (98.2 %) 20 (100 %)

Collection Process 21 (100 %) 585 (97 %) 20 (100 %)

Legal Basis 19 (90.5 %) 527 (87.4 %) 6 (30 %)

Third-Party Entity 13 (61.9 %) 458 (76 %) 12 (60 %)

Dictionary phrase Data Protection Officer 15 (71.4 %) 447 (74.1 %) 9 (45 %)

Legitimate Interest 19 (90.5 %) 433 (71.8 %) 1 (5 %)

Rectification 19 (90.5 %) 538 (89.2 %) 4 (20 %)

Erasure 20 (95.2 %) 567 (94.0 %) 4 (20 %)

Data Portability 17 (81.0 %) 380 (63.0 %) 4 (20 %)

Supervising Authority 14 (66.7 %) 465 (77.1 %) 0 (0 %)

Total number of privacy policies 21 603 20

formation collected or shared, their purpose, and the

collection process slightly less than those in Austria

and Ireland. In comparison to Germany and Aus-

tria, the number of statements regarding the legal ba-

sis of processing (Article 6 of the GDPR) in Ireland

is relatively limited. It might have been expected

that the coverage numbers for the first-party collec-

tion/use category and the legal basis for processing

would be comparable to those observed in Austria

and Germany. Building on that, we can conclude that

the privacy policies in all three countries are compre-

hensive in their descriptions of the type of data col-

lected or used by public administrations, as well as

the purposes for which such data is collected. How-

ever, the legal basis for collecting and processing per-

sonal data, a critical requirement for GDPR confor-

mity, is not frequently included in Irish privacy poli-

cies. Furthermore, we may notice that the third-party

entity attribute is addressed less frequently than the

third-party collection/use category in all three coun-

tries, meaning that privacy policies do not disclose the

identity of third parties involved in data practices.

In regard to the results obtained by searching the

dictionary phrases in the privacy policies, a finding

is that the majority of privacy policies in Austria

and Germany contain the phrase “legitimate interest,”

which is one of the six legal bases of processing as

outlined in Article 6 of the GDPR. A visual inspec-

tion of the privacy policies in question reveals that, in

the case of Austrian privacy policies, there are com-

mon use cases of legitimate interest as the legal basis

of processing. One such use case is the analysis of log

data to ensure the security of personal data. However,

we also observed relatively questionable use cases

for this legal basis, including the use of YouTube or

Vimeo to display online offers, the analysis of user

behavior to tailor displayed advertisements, and the

usage of third-party fonts.

In the case of Germany and Austria, we can ob-

serve high coverage for the terms “rectification” and

“erasure,” which may indicate two specific user rights

outlined in the GDPR: Article 16 (right to rectifica-

tion) and Article 17 (right to erasure). In contrast,

the aforementioned user rights are not observed to be

covered to the same extent in the privacy policies of

the Irish medium-sized towns.

Similarly, the phrase “data portability,” which

refers to Article 20 of the GDPR (the right to data

portability), is less prevalent in Irish privacy policies.

On the contrary, the privacy policies of Germany and

Austria frequently employ this expression.

The observed coverage of the phrases “data pro-

tection officer” and “supervising authority” is compa-

rable in Austria and Germany. However, only approx-

imately 50 % of the Irish privacy policies included in-

formation on the designation of a data protection of-

ficer, while none of the privacy policies contained the

specific phrase “supervising authority.” Searching for

a reason for the latter observation, we conducted a

more thorough investigation into the content of the

Irish privacy policies. This revealed an instance in

which the term “supervisory authority” was used in

place of “supervising authority.” Furthermore, an ad-

ditional search was conducted for the name of the na-

tional supervising authority in Ireland within the Irish

privacy policies, which yielded the result of the Data

Protection Commission (DPC). However, our investi-

gation revealed that only six privacy policies (30 %)

provided users with information about the commis-

sion and its functions.

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

66

5.2 Second Assessment in 2024

Based on our observations about the Irish privacy

policies in 2023, we conducted a follow-up assess-

ment in October 2024 to investigate whether any en-

hancements had been implemented. We detail our

findings for each town, organizing towns with com-

parable results into groups.

The privacy policy of County Wexford only con-

tained statements regarding the use of cookies and

Google Analytics, and no changes were observed.

The policy lacked the inclusion of required statements

by the GDPR, such as the afforded GDPR user rights

or the legal bases for data processing.

The landing page of Celbridge in Kildare County

displayed contact information but lacked a link to a

privacy policy. The websites of Naas and Newbridge,

both located in Kildare County, also exhibited a sim-

ilar design. The privacy policy of Kildare County

Council did not reflect any changes compared to 2023

and included statements regarding the collection of

personal data. However, it did not provide clear le-

gal bases for processing these data. On the positive

side, the privacy policy provided definitions regard-

ing technical terms, such as IP address, and included

a reference to the Irish Data Protection Commission.

Mullingar’s privacy policy did not show any al-

terations and contained declarations on the collected

personal data, their legal bases of processing, and user

rights. However, the privacy policy lacked informa-

tion on the identity of the data protection officer and

the supervisory authority.

The privacy policy of Athlone did not reflect any

changes compared to the 2023 version. The privacy

policy provided disclosures on the types of collected

personal data and offered generic statements regard-

ing user rights. A notable statement was permission

for the indefinite storage of comments left on the web-

site and their associated metadata.

The website of Balbriggan redirected its privacy

policy webpage to the privacy policy of its County

Council, i. e., that of Fingal County. This privacy pol-

icy did not reflect any changes. The text included the

types of personal information collected and the pur-

poses for which they were being processed, but did

not specify the legal basis for the processing. Addi-

tionally, no information was provided regarding the

rights of users according to the GDPR. The text of the

privacy policy for Fingal County was similar.

Portlaoise (Laois County) updated its privacy pol-

icy to include a detailed list of the personal data col-

lected. In addition, the privacy policy included a spe-

cific section dedicated to GDPR user rights. However,

a link entitled "Exercise these rights" resulted in an er-

ror message (404) upon accessing the page at the time

of writing. Nevertheless, the contact information for

the Data Protection Commissioner was provided.

The privacy policy of Carlow did not indicate

any changes. However, this privacy policy was al-

ready one of the more comprehensive privacy poli-

cies among the Irish privacy policies that were ana-

lyzed. The privacy policy disclosed the collected per-

sonal data and the purpose of its collection, as well

as the GDPR provisions regarding the legal bases of

processing (Article 6 of the GDPR). Additionally, the

policy included the contact details of the data pro-

tection officer. Moreover, a document outlining the

users’ rights regarding the collected personal data was

provided as a link at the bottom of the privacy pol-

icy web page. The privacy policy of Galway City &

Council was similar in this sense.

Reviewing the website of Ennis revealed the ab-

sence of a privacy policy. The privacy policy of the

website of its County Council, Clare, was updated

compared to 2023. The updated version reorganized

certain elements of the previous version. For exam-

ple, the policy now incorporates a section address-

ing third-party links and disclosure regarding the col-

lection of special category data (Article 9(1) of the

GDPR). Moreover, the section on the purpose of pro-

cessing was updated and now provides a clear de-

scription of the legal bases for processing. The trans-

fer of personal data to the US is now reported to

be based on the Transatlantic EU-US Data Privacy

Framework (European Commission, 2023a).

The privacy policy of Kilkenny did not undergo

any modifications. While the policy included the pur-

poses of data processing, it did not include the legal

bases of processing. Furthermore, the vagueness of

some statements was noteworthy. For instance, the

statements “The personal details we are most likely

to collect [. . . ]” and “These are the ways we are

most likely to use your information” indicate a lack

of clarity and complete transparency (Liu et al., 2016;

Lebanoff and Liu, 2018; Malik et al., 2023).

The privacy policy of Navan (Meath County),

Louth County, and Limerick City and Council re-

mained unchanged. While the texts contained the pur-

poses of data collection and the user rights regard-

ing these data, they did not contain the concrete legal

bases for processing these data. Contact information

was provided for the data protection officer and the

Office of the Data Protection Commissioner.

The privacy policy of Bray (Wicklow County) did

not indicate any changes. Although the policy listed

the types of personal data that would be collected and

the purposes of collection, it did not list the legal

bases for processing these data. In particular, this pri-

Privacy Policies in Medium-Sized European Town Administrations: A Comparative Analysis of English and German-Speaking Countries

67

vacy policy included a web form for submitting data

protection requests. However, there was no descrip-

tion of the entity that would receive such a request.

The privacy policy of Waterford City & Coun-

cil added dedicated sections regarding the usage of a

third-party provider, CookieYes, to control and reg-

ulate the usage of cookies, as well as a section on

website analytics. Furthermore, the policy enumer-

ated users’ rights according to the GDPR and pro-

vided contact information for the data protection offi-

cer and the Data Protection Commission.

Finally, no changes were indicated in the privacy

policies of the Tralee and Kerry County Council.

5.3 Summary of the Assessments

Based on the comparative analysis of the privacy

policies between the countries in 2023 and the ad-

ditional assessment of the Irish privacy policies in

2024, we can conclude that while German and Aus-

trian medium-sized towns share similar results, Irish

medium-sized towns fell behind in:

1. providing users with fully transparent information

regarding the legal bases for processing according

to Article 6 of the GDPR;

2. informing users about their rights according to Ar-

ticles 13 to 22 of the GDPR; and

3. providing users with information about con-

tacts such as the data protection officer and the

Data Protection Commission according to Arti-

cles 13(2)(d) and 14(2)(e) to be able to exercise

their right to lodge a complaint.

Upon examination of individual towns, we did not

observe any regional differences between the towns

regarding GDPR coverage. The two towns with the

lowest GDPR coverage within the Austrian list are lo-

cated in the Lower Austria (Niederösterreich) region.

In Germany, the distribution of towns across the

states was uniform, and no noticeable trend or pattern

emerged concerning GDPR coverage.

In the case of Ireland, the towns with the most ex-

tensive GDPR coverage were distributed across dif-

ferent counties. At the same time, among the towns

exhibiting the lowest level of GDPR coverage, we

identified three towns concentrated within a single

county that demonstrated notable deficiencies in their

privacy policies.

6 DISCUSSION

The present study examined the landscape of pri-

vacy policies of medium-sized town administrations

in three European countries with the objective of gain-

ing a detailed understanding of their coverage of data

practice disclosures required by the GDPR. By em-

ploying a quantitative analysis approach consisting

of deep learning classification based on fine-tuned

BERT models and a dictionary analysis for GDPR-

related phrases, we analyzed and evaluated the extent

to which the privacy policies addressed the mandatory

requirements of the GDPR. This analysis was com-

plemented by a qualitative approach, which involved

a detailed examination of the privacy policies, espe-

cially the shortcomings of the Irish policies. Conse-

quently, we depicted the landscape of privacy policies

of the websites of city administrations in medium-

sized towns in Austria, Germany, and Ireland.

The Austrian and German towns included in our

sample set exhibited higher and often similar cover-

age of the data practice categories, attributes, and dic-

tionary phrases. However, Irish towns demonstrated

lower coverage, as numerous towns lacked essential

statements in their privacy policies, including users’

rights, the designation of a data protection officer, and

the supervising authority. This deficiency suggests

a potential lack of awareness of the descriptions and

disclosures required in a privacy policy by the GDPR,

as stipulated in Articles 12 to 14 of the GDPR.

Although the GDPR came into effect in May

2018, at the beginning of our study, we anticipated

that the majority of privacy policies would achieve

medium to medium-high GDPR coverage due to

three underlying factors discovered in previous stud-

ies (Karyda and Mitrou, 2016; Aberkane et al., 2022;

Saemann et al., 2022):

• Insufficient Legal Expertise. Medium-sized

town administrations may lack sufficiently trained

personnel possessing the essential expertise to ef-

fectively implement GDPR requirements and to

formulate comprehensive privacy policies.

• Resource Constraints. Medium-sized town ad-

ministrations may face resource limitations that

inhibit their ability to develop and maintain

GDPR-compliant privacy policies, leading them

to outsource this responsibility.

• Fear of the Unknown. Employees of medium-

sized town administrations may be concerned

about potential sanctions arising from complaints

regarding GDPR-related violations, potentially

leading them to engage in opaque data manage-

ment practices, thereby undermining efforts to

foster transparency in data handling.

These are consistent with the findings of (Becker

et al., 2021), which highlights an important issue: re-

source inequalities between medium-sized towns and

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

68

metropolitan cities. In their analysis of the existing

literature, they point out that medium-sized towns are

often at a disadvantage relative to metropolitan ar-

eas in terms of both human and financial resources,

and they typically lack adequate resources dedicated

to marketing and branding initiatives. Such resource

limitations could potentially explain, at least in part,

the relatively low observed GDPR coverage in the pri-

vacy policy of these areas.

Further research could explore the relationship be-

tween resource constraints and the quality of privacy

policies. Such investigations might include interviews

with the chief digitalization officers and data protec-

tion officers in medium-sized towns to gain insight

into the nuances of resource allocation and manage-

ment in these areas. The goal of this research would

be to understand how, or if, such resource constraints

influence the maintenance and development of the

digital presence of medium-sized towns, including

their privacy policies.

Viewing our findings from the sociological per-

spective, it can be argued that the lack of transparency

regarding data practices and user rights in the pri-

vacy policies of medium-sized town website admin-

istrations effectively hinders citizens from being able

to exercise their fundamental rights and using their

agency, i. e., their means of taking action (Grund-

mann, 2020; Versalovic et al., 2022), regarding their

personal data whenever they see the need. Consider-

ing Sen’s capability approach (Sen, 1993; Robeyns,

2021), providing citizens with the capability to exer-

cise their rights fosters the functionality of develop-

ment of trust between citizens and the administrations

of medium-sized towns. Consequently, citizens may

be more inclined to utilize the digital services offered

by their town’s public administrations.

The availability of trained models for the English

and German languages, as well as the language pro-

ficiency of the authors, constituted a limitation on

the scope of this research. Given that the analysis

methods were based on the aforementioned natural

language processing techniques and involved man-

ual checks of the content of the privacy policies, the

investigation was restricted to English and German-

language privacy policies. Consequently, the findings

were constrained to countries within the EU where

English or German are the primary languages. These

limitations precluded an analysis of privacy policies

in other languages and regions. Thus, the results are

not generalizable to all EU countries.

A comparison between the accuracy of data prac-

tice disclosures in the privacy policies and actual op-

erational practices would have required manual fact-

checking and gaining access to the internal system

infrastructure of the town administration’s websites.

This step was omitted due to the requirement to al-

locate considerable resources and was not within the

scope of this research.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the research

findings contribute to a more profound understanding

of the current state of privacy policies in English and

German-speaking European countries. The findings

establish a foundation for future research on privacy

policies in rural areas and studies in medium-sized

towns, including investigations into trust relationships

and participation. Specifically, we propose the fol-

lowing areas of research for further investigation:

• Investigate whether there is a measurable correla-

tion between the extent of GDPR coverage and the

resources available to towns, specifically regard-

ing trained staff and the allocation of dedicated

funding for privacy and security measures.

• Extend the application of our approach to other

countries that use different definitions for mid-

sized towns to assess its universal applicability.

• Conduct similar analyses on privacy policies that

fall under the legislation of other comparable reg-

ulations, including but not limited to the Califor-

nia Privacy Rights Act (CPRA).

7 CONCLUSION

This study examined the privacy policies of medium-

sized town administrations in Austria, Germany, and

Ireland to shed light on their GDPR coverage. We

conducted a quantitative analysis using fine-tuned

BERT models and GDPR-related dictionary phrases

to assess the extent to which the policies in question

addressed the requirements outlined in the GDPR. We

measured the coverage of data disclosure practices

and the extent to which users were informed about

their rights to their collected personal data. We per-

formed additional qualitative analyses to enhance our

quantitative findings.

Our analysis indicates that the privacy policies

of medium-sized town administrations in Austria

and Germany adequately cover GDPR-related disclo-

sures. However, there is still room for improvement

in Ireland. Recommended enhancements include pro-

viding more comprehensive information about users’

rights concerning their personal data and clearly stat-

ing the legal basis for data processing in all cases.

Further recommended improvements include refer-

encing the supervising authority in Ireland, as well

as the contact information for data protection officers.

We suggest that the Data Protection Commission in

Privacy Policies in Medium-Sized European Town Administrations: A Comparative Analysis of English and German-Speaking Countries

69

Ireland provides guidance to medium-sized towns to

address the identified shortcomings.

We raise concern regarding the use of legitimate

interests as the legal basis for data collection and pro-

cessing in German and Austrian privacy policies un-

less serving an unambiguous and justifiable purpose.

We advocate for grounding the collection, sharing,

and processing of personal data on a more transpar-

ent legal basis to foster greater public trust in the data

practices of their respective administrations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author expresses his gratitude to Ivan Borger

and Manh Tin Nguyen for their invaluable assistance

with an early version of this work. We also express

our sincere appreciation to the anonymous review-

ers for their constructive feedback. The author used

ChatGPT, Grammarly, and DeepL Write to address

typographical errors, grammatical inaccuracies, and

issues of awkward phrasing. This project received

funding from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft

(DFG, German Research Foundation) – 462287308

(HU 3005/2-1 & BE1422/27-1).

REFERENCES

Aberkane, A.-J., Broucke, S. V., and Poels, G. (2022).

Investigating organizational factors associated with

GDPR noncompliance using privacy policies: A ma-

chine learning approach. In 2022 IEEE 4th Inter-

national Conference on Trust, Privacy and Security

in Intelligent Systems, and Applications (TPS-ISA),

pages 107–113. IEEE.

Adhikari, A., Das, S., and Dewri, R. (2023). Evolution

of Composition, Readability, and Structure of Privacy

Policies over Two Decades. Proceedings on Privacy

Enhancing Technologies, 2023(3):138–153.

Arora, S., Hosseini, H., Utz, C., Kumar, V. B., Dhellemmes,

T., Ravichander, A., Story, P., Mangat, J., Chen, R.,

Degeling, M., Norton, T., Hupperich, T., Wilson,

S., and Sadeh, N. (2022). A Tale of Two Regula-

tory Regimes: Creation and Analysis of a Bilingual

Privacy Policy Corpus. In Proceedings of the 13th

Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation,

LREC 2022, pages 5460–5472, Paris, France. ELRA.

Becker, J., Distel, B., Grundmann, M., Hupperich, T., Ker-

sting, N., Löschel, A., Parreira do Amaral, M., and

Scholta, H. (2021). Challenges and potentials of dig-

italisation for small and mid-sized towns: Proposition

of a transdisciplinary research agenda. ERCIS Work-

ing Papers. Number: 36 Publisher: University of

Münster, European Research Center for Information

Systems (ERCIS).

Central Statistics Office Republic of Ireland (2021). E2016

- Population and Actual and Percentage Change 2011

to 2016.

Degeling, M., Utz, C., Lentzsch, C., Hosseini, H., Schaub,

F., and Holz, T. (2019). We Value Your Privacy ... Now

Take Some Cookies: Measuring the GDPR’s Impact

on Web Privacy. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual

Network and Distributed System Security Symposium,

NDSS ’19, Reston, VA, USA. Internet Society.

Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K., and Toutanova, K.

(2018). BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional

Transformers for Language Understanding. CoRR,

abs/1810.04805. arXiv:1810.04805 [cs].

Dias, G. P., Gomes, H., and Zúquete, A. (2013). Privacy

Policies in Web Sites of Portuguese Municipalities:

An Empirical Study. In Advances in information sys-

tems and technologies, pages 87–96. Springer.

Directorate-General for Communication (2014). Special

Eurobarometer 386: Europeans and their Languages.

European Commission (2023a). Adequacy Decision for the

EU-US Data Privacy Framework. https://commission

.europa.eu/document/fa09cbad-dd7d-4684-ae60-be0

3fcb0fddf_en.

European Commission (2023b). Europe’s Digital Decade |

Shaping Europe’s digital future.

European Data Protection Board (2023). The Icelandic SA:

The municipalities of Reykjavík, Reykjanesbær, Kó-

pavogur, Hafnarfjörður, and Garðabær fined for the

use of Google Workspace in Education. https://ww

w.edpb.europa.eu/news/national-news/2024/iceland

ic-sa-municipality-reykjavik-fined-isk-2000000-use

-google-workspace_en and https://www.edpb.europa.

eu/news/national-news/2024/icelandic-sa-municipal

ity-reykjanesbaer-fined-eur-16590-use-google_en

and https://www.edpb.europa.eu/news/national

-news/2024/icelandic-sa-municipality-kopavog

ur-fined-eur-19907-use-google-workspace_en

and https://www.edpb.europa.eu/news/national

-news/2024/icelandic-sa-municipality-hafnarfjo

rdur-fined-eur-18580-use-google_en and https:

//www.edpb.europa.eu/news/national-news/2024/i

celandic-sa-municipality-gardabaer-fined-eur-16-5

90-use-google-workspace_en.

Grundmann, M. (2020). Agency. Handbuch Ganztagsbil-

dung, pages 1707–1717.

Helfrich, M. (2023). Datenschutzrecht. dtv Beck Texte

5772. dtv, München, 15. auflage, stand: 15. januar

2023, sonderausgabe edition.

Hollman, A. K., Obermier, T. R., and Burger, P. R. (2021).

Rural Measures: A Quantitative Study of the Ru-

ral Digital Divide. Journal of Information Policy,

11:176–201.

Hosseini, H., Degeling, M., Utz, C., and Hupperich,

T. (2021). Unifying Privacy Policy Detection.

Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies,

2021(4):480–499.

Hosseini, H., Utz, C., Degeling, M., and Hupperich, T.

(2024). A Bilingual Longitudinal Analysis of Pri-

vacy Policies Measuring the Impacts of the GDPR and

the CCPA/CPRA. Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing

Technologies, 2024(2):434––463.

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

70

Hosseini, S., Frank, L., Fridgen, G., and Heger, S. (2018).

Do Not Forget About Smart Towns. Business & Infor-

mation Systems Engineering, 60(3):243–257.

Kamara, I. and De Hert, P. (2018). Understanding the Bal-

ancing Act Behind the Legitimate Interest of the Con-

troller Ground: A Pragmatic Approach. Brussels Pri-

vacy Hub Working Paper, 4(12).

Karyda, M. and Mitrou, L. (2016). Data Breach Notifi-

cation: Issues and Challenges for Security Manage-

ment. In Mediterranean Conference on Information

Systems.

Kohlschütter, C., Fankhauser, P., and Nejdl, W. (2010).

Boilerplate Detection Using Shallow Text Features. In

Proceedings of the Third ACM International Confer-

ence on Web Search and Data Mining, WDSM ’10,

pages 441–450, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Kyi, L., Ammanaghatta Shivakumar, S., Santos, C. T.,

Roesner, F., Zufall, F., and Biega, A. J. (2023). In-

vestigating Deceptive Design in GDPR’s Legitimate

Interest. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference

on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI 2023,

New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Lai, C. M. T. and Cole, A. (2022). Levels of public trust

as the driver of citizens’ perceptions of smart cities:

the case of hong kong. Procedia Computer Science,

207:1919–1926.

Lankshear, C. and Knobel, M. (2008). Digital literacies:

Concepts, policies and practices, volume 30. Peter

Lang.

Lebanoff, L. and Liu, F. (2018). Automatic Detection

of Vague Words and Sentences in Privacy Policies.

In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empiri-

cal Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages

3508–3517.

Liu, F., Fella, N. L., and Liao, K. (2016). Modeling Lan-

guage Vagueness in Privacy Policies Using Deep Neu-

ral Networks. In 2016 AAAI Fall Symposium Series.

Malik, G., Yildirim, S., Cevik, M., and Bener, A. (2023).

An Empirical Study on Vagueness Detection in Pri-

vacy Policy Texts. In Canadian AI.

Mhaidli, A., Fidan, S., Doan, A., Herakovic, G., Srinath,

M., Matheson, L., Wilson, S., and Schaub, F. (2023).

Researchers’ Experiences in Analyzing Privacy Poli-

cies: Challenges and Opportunities. Proceedings on

Privacy Enhancing Technologies, 2023(4):287–305.

Milbert, A. and Porsche, L. (2022). Small towns in ger-

many. Technical report, Federal Institute for Research

on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development

(BBSR) within the Federal Office for Building and

Regional Planning (BBR).

Montani, I., Honnibal, M., Boyd, A., Van Landeghem, S.,

and Peters, H. (2020). spaCy: Industrial-strength Nat-

ural Language Processing in Python.

Mozilla (2023). Readability.js.

OECD and European Commission (2020). Cities in the

World: A New Perspective on Urbanisation. OECD

Urban Studies. OECD.

Presthus, W. and Sønslien, K. F. (2021). An analysis of vio-

lations and sanctions following the gdpr. International

Journal of Information Systems and Project Manage-

ment, 9(1):38–53.

Python Software Foundation (2023). Requests.

Reis, J., Amorim, M., Melão, N., and Matos, P. (2018). Dig-

ital Transformation: A Literature Review and Guide-

lines for Future Research. In Rocha, Á., Adeli, H.,

Reis, L. P., and Costanzo, S., editors, Trends and

Advances in Information Systems and Technologies,

pages 411–421, Cham. Springer International Pub-

lishing.

Robeyns, I. (2021). The Capability Approach. In The Rout-

ledge handbook of feminist economics, pages 72–80.

Routledge.

Saemann, M., Theis, D., Urban, T., and Degeling, M.

(2022). Investigating GDPR Fines in the Light of Data

Flows . Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technolo-

gies, 2022(4):314–331.

Scrapy project (2023). Parsel Library.

Selenium (2023). Selenium WebDriver.

Sen, A. (1993). Capability and Well-Being. Clarendon

Press, Oxford.

Statisik Austria (2023). Österreich Bevölkerung zu Jahres-

/Quartalsanfang 2022.

Stern, M. J., Adams, A. E., and Elsasser, S. (2009). Dig-

ital Inequality and Place: The Effects of Technologi-

cal Diffusion on Internet Proficiency and Usage across

Rural, Suburban, and Urban Counties. Sociological

Inquiry, 79(4):391–417.

Versalovic, E., Goering, S., and Klein, E. (2022). Data, Pri-

vacy, and Agency: Beyond Transparency to Empow-

erment. The American Journal of Bioethics, 22(7):63–

65.

Voigt, P. and von dem Bussche, A. (2017). The EU Gen-

eral Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): A Practical

Guide. Springer International Publishing.

Wikipedia (2023). List of municipalities in Germany. Page

Version ID: 1169869702.

Wilkerson, J. and Smith, J. (2023). Identifying tomorrow’s

smart city privacy challenges: A review of literature.

In 25th Proceedings of the Southern Association for

Information Systems Conference, Hilton Head, SC,

USA.

Wilson, S., Schaub, F., Dara, A. A., Liu, F., Cherivirala, S.,

Leon, P. G., Andersen, M. S., Zimmeck, S., Sathyen-

dra, K. M., Russell, N. C., Norton, T. B., Hovy, E.,

Reidenberg, J., and Sadeh, N. (2016). The Creation

and Analysis of a Website Privacy Policy Corpus. In

Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Associ-

ation for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long

Papers), volume 1: Long Papers of ACL ’16, pages

1330–1340, Stroudsburg, PA, USA.

Privacy Policies in Medium-Sized European Town Administrations: A Comparative Analysis of English and German-Speaking Countries

71