Enhanced Graph Representations of Chromatin Interaction Networks

Edgars Celms

a

, Lelde Lace

b

, Gatis Melkus

c

, Peteris Rucevskis

d

, Sandra Silina

e

,

Andrejs Sizovs

f

and Juris Viksna

g

Institute of Mathematics and Computer Science, University of Latvia, Raina Bulvaris 29, Riga, Latvia

{edgars.celms, lelde.lace, gatis.melkus, peteris.rucevskis, sandra.silina, andrejs.sizovs, juris.viksna}@lumii.lv

Keywords:

Chromatin Interaction Networks, Graph Representations, Network Topology, Graph Patterns.

Abstract:

We present a novel extension of graph representations of chromatin interaction networks incorporating edge

directionality and vertex label assignments and focus on patterns defined by different types of 3-cliques that can

occur under such assignments. 3-cliques are chosen for their simplicity and comparative ubiquity in chromatin

interaction graphs; also, our previous work indicates a certain level of biological significance that can be

assigned to them. Here we explore statistical distributions of different types of directionality- and strand-

based 3-cliques patterns in two well-curated promoter capture Hi-C data sets and observe that the pattern

distributions strongly deviate from random, if they are considered in the context of a number of additional

features. These observations provide a good justification for further exploration of chromatin interaction data

sets using network representations that include edge directionality and node label assignments and indicate a

possibility that these annotation features could be related to some specific underlying biological mechanisms.

1 INTRODUCTION

In this work, we explore the extension of graph rep-

resentations of chromatin interaction networks with

edge directionality and vertex label assignments. The

work was motivated by our previous studies, in which

we have shown the benefits of analysing chromatin in-

teraction networks in terms of topological features of

network representations by undirected graphs (Lace

et al., 2020; Viksna et al., 2020) as well as indica-

tions of the usefulness of enriching these representa-

tions by additional vertex and edge labelling and edge

directionality. The intention is to include in graph rep-

resentations to the maximum extent the available in-

formation about DNA spatial structure, with the pos-

sibility of 3D genome reconstruction from chromoso-

mal contact maps already been (at least, in principle)

demonstrated (Morlot et al., 2016).

The significance of DNA 3D structure became

well-acknowledged in 80s as an ’unanticipated dis-

covery’ (Schleif, 1992), backed by evidence of mi-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9608-3792

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7650-2355

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3077-6809

d

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-6189-2008

e

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-3917-9026

f

https://orcid.org/0009-0004-6958-9965

g

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2283-2978

croscopy and targeted wet-lab experiment data. As

significant structural features were acknowledged

loops — free segments of DNA lacking interaction

with other DNA parts. The other types of well-

defined DNA structural features, however, were dis-

covered (or proposed) only after advances in chro-

matin conformation capture techniques. The first

comprehensive analysis of chromatin interactions was

presented in (Lieberman-Aiden et al., 2009); the au-

thors introduce the notion of compartments – parti-

tion of each chromosome in 2 loci (arbitrarily named

A and B) such that contacts within each set are en-

riched and contacts between them are depleted. The

provided compartment definition is not strictly for-

malised, though, and the notion of compartments later

seems to be used by other researchers in similar, but

not necessarily exactly the same, contexts.

Already well-defined and well-recognised fea-

tures are TADs (Topologically Associated Domains),

which were initially proposed in (Dixon et al., 2012)

with more precise definition and detection techniques

developed in (Rao et al., 2014). TADs can be con-

sidered as closely interacting continuous segments of

DNA and are ’well defined’ in the sense that they cor-

respond to obvious and usually well-separated activ-

ity spots on diagonals of heatmaps of Hi-C data. In

(Rao et al., 2014), a robust procedure for automated

loop identification from heatmaps is proposed by us-

Celms, E., Lace, L., Melkus, G., Rucevskis, P., Silina, S., Sizovs, A. and Viksna, J.

Enhanced Graph Representations of Chromatin Interaction Networks.

DOI: 10.5220/0013173100003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 1, pages 579-585

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

579

ing a number of clustering methods. Potential biolog-

ical mechanisms for forming TADs are well described

in (Matharu and Ahituv, 2015). In (Grubert et al.,

2020) is provided a very recent statistical analysis of

loop and TAD cell type specificity for 24 human cell

types using datasets from ENCODE portal.

Another interesting (and not too widely studied)

features of interaction data are FIREs (Frequently

Interacting Regions) introduced in (Schmitt et al.,

2016). FIREs can be considered as small sub-

segments of TADs actively interacting with other

regions within them. The authors also propose a

method for FIRE identification and show that they

have strong tissue-specificity (on the basis of 21 tissue

data). A recent review of structural features of chro-

matin interactions (that partially also acknowledges

our still limited understanding of them) was presented

in (Eagen, 2018) and discusses all four structural fea-

tures mentioned above: loops, compartments, TADs,

and FIREs. The authors also provide a computation-

ally more robust definition of compartments as clus-

ters of two or more strongly interacting TADs.

Regarding the biological role of DNA structural

features, whilst in general it is already well acknowl-

edged (Schleif, 1992), the opinion of the importance

or role of particular structural features still somewhat

varies (that partially might be explained by the use of

different experimental techniques or data processing),

albeit in general consensus that all these structures

have important biological roles seems to be reached.

A number of potential biological mechanisms for this

have also been proposed (Catarino and Stark, 2018;

Mora et al., 2016; Schoenfelder et al., 2010).

Whilst processed chromatin interaction datasets

can naturally be considered as large weighted net-

works, there have been comparatively few studies that

have treated the data explicitly as such network. Most

often, one or several different heatmap (also known as

Hi-C interaction map) representations are used, which

provide a ’general picture’ but are certainly lacking

in detail. One of the first studies that tries to anal-

yse Hi-C data as the network is (Siahpirani et al.,

2016); the authors use a number of known cluster-

ing methods (as well as propose their own) for Hi-C

data analysis; the results allow us to differentiate be-

tween four (two human, two mice) cell lines. In (Thi-

bodeau et al., 2017) ML-based network analysis was

applied to data from 3 cell lines, and the authors have

identified several tens of small subgraphs (’graphlets’

with 2-5 vertices) that were over-represented in the

interaction networks; some of these were shown to be

cell type-specific, and some were not. Also (Javierre

et al., 2016) provides examples of a few small sub-

graphs of interaction networks, together with possible

explanations of their biological role. The most ex-

plicit network-oriented approach was probably used

by (Schulz et al., 2018), where the authors present an

algorithm for finding common single linkage clusters

(called δ-teams) in a set of interaction graphs. The

method was also applied to 3 interaction networks

generated by (Dixon et al., 2012), although without

strong conclusions being drawn.

One of the difficulties in analysing networks at the

graph topology level is the very wide range of den-

sities of graphs obtained from measured interaction

data. Thus, although the feasibility of reconstruction

of DNA 3D structure from chromatin contact maps

has been demonstrated (Morlot et al., 2016) in princi-

ple, the amount of information about 3D structure that

can be extracted from experimentally obtained Hi-C

datasets is a completely different matter.

Nevertheless, there is steadily increasing interest

in graph-based chromatin structure models (Pancaldi,

2023), including proposals of some very high abstrac-

tion level representations (Dotson et al., 2022; Tan

et al., 2018). Our previous results (Lace et al., 2020;

Viksna et al., 2020) have also shown that topologi-

cal properties of chromatin interaction graphs can be

successful for differentiation between different tissue

and cell types and that certain small network substruc-

tures can be well associated with groups of genes with

similar activity modes. In the background context, we

expect that the proposed extensions could broaden the

classes of networks to which the significance of spe-

cific topological features can be applied.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Topological Patterns of 3-Cliques

The use of edge directionality is particularly appropri-

ate for promoter capture Hi-C (PCHi-C) data, where

it is already implicitly defined by interactions be-

ing measured between ’baits’ (promoters) and ’other

ends’ (some of which can also be promoters). Thus,

PCHi-C data sets can inherently be viewed as directed

graphs, the challenge is to gain some understanding

whether and/or how this directionality can be associ-

ated with biologically interesting features captured by

these data sets.

In our previous work we have successfully

demonstrated biological significance of a number of

specific topological features in PCHi-C graphs (and

also Hi-C graphs in general). The most of these topo-

logical features were defined by the presence of small

subnetworks, which we refer to as ’patterns’ (’mo-

tifs’ is another commonly used term in computational

BIOINFORMATICS 2025 - 16th International Conference on Bioinformatics Models, Methods and Algorithms

580

biology for such subnetworks, although it tend to im-

ply assignment of also some biological meaning; a

particularly elaborate approach of using subnetworks

in biological network analysis has been developed in

(Yaveroglu et al., 2015; Sarajlic et al., 2016; Przulj

and Malod-Dognin, 2016) by a research team who re-

fer to such substructures as ’graphlets’).

One of the simplest types of such identified topo-

logical features were k-cliques – fully connected sub-

graphs of k vertices. k-cliques provided good discrim-

inatory power between chromatin interaction graphs

between different tissues and cell types (Lace et al.,

2020), and clique-rich regions can also be well asso-

ciated with increased transcriptional activity (Melkus

et al., 2023). Due to complexity of k-clique finding

growing exponentially with k, we have limited explo-

ration of k-cliques for values of k = 3...5. Although,

when present, 4- and 5-cliques exhibited particularly

good discriminatory power, with the analysed Hi-C

data sets defining comparatively sparse graphs their

numbers were quite limited, and the most abundant

and particularly significant turned out to be such sim-

ple topological structures as 3-cliques. The pres-

ence and biological significance of specific types of

3-cliques has also been justified by the proposed as

well as experimentally observed transitivity of CTCF-

mediated chromatin loops (Wang et al., 2021).

Due to this it also appears to be very natural to

base the initial assessment of edge directionally and

labelling on the analysis of different types of 3-cliques

that can be obtained by such assignments. We call

these clique types patterns and consider here patterns

that are defined by edge directionality (patterns A, B,

C and D) and by strand assignments to edge endpoints

(patterns X, Y and Z).

In representations of PCHi-C data, 3-clique pat-

terns are defined by the order of their vertices on chro-

mosomes and the direction of edges between them –

up to symmetries, this leads to 4 different types of pat-

terns A, B, C and D (Figure 1). The underlying data

do not imply that A, B, C and D patterns can be di-

rectly associated with different 3D conformations of

chromatin structure. However, they affect the rela-

tive locations of genes and their promoting regions on

DNA loops formed by 3-cliques. Patterns of types A,

B and C are all defined by two promoters, and one can

expect that they will occur with similar frequencies.

Type D patterns, however, are defined by three pro-

moters. Assuming that for all the edges the probabil-

ities for their ’other ends’ to happen to be also ’baits’

are completely random, the probability of pattern to

have three promoters by chance would be p = N

p

/N

e

,

with N

p

being the total number of promoters and N

e

being the total number of edge endpoints for a par-

ticular chromosome. Such assumption would lead to

the expected frequencies of patterns A, B, and C be-

ing 1/(p + 3) and the frequency of pattern D being

p/(p + 3). In practice, however, the probabilities p

are not distributed to edges completely randomly, but

depend on multiple other factors (e.g. node degree

distribution), some of which are data set specific. Due

to this it is difficult to assign meaningful exact expec-

tation frequencies of patterns, but we can assume that

the types A, B and C should be equally frequent, and

the type D is expected to occur less frequently.

Another natural way to partition 3-cliques into

subtypes is by defining patterns according to the

strand specificity of interacting regions associated

with endpoints of edges. Strand-specificity of inter-

acting regions likely could be of relevance for vari-

ous types of chromosome conformation capture tech-

niques, not only PCHi-C, provided that such infor-

mation can be extracted from measurement data. As-

suming that the endpoint regions of an observed chro-

matin interaction can be reliably assigned to specific

chromosome strands, we, up to symmetries, obtain

three types of patterns: X, Y and Z (Figure 1). In

this case, different patterns can already be directly

related to different folding of DNA in 3D space, al-

though the significance of this might start to manifest

only for short-range interactions. Clique node allo-

cation to strands is characterised by node sequence

a → b → c, with a, b, c denoting one of the two strands

A and B, which provides 8 possible allocations. Two

of these correspond to type X patterns (A → A → A

and B → B → B), two correspond to type Y patterns

(A → B → A and B → A → B), and four to type Z

patterns (A → A → B, A → B → B, B → B → A and

B → A → A). Thus, with 3-clique vertices being ran-

domly located on strands, patterns of types X and Y

are expected to occur with the probabilities 1/4 each

and pattern of type Z with the probability 1/2.

Figure 1: Four types of patterns of 3-cliques of chromatin

interactions defined by edge directionality: A, B, C and D

(left); and three types of 3-clique patterns defined by gene

locations on strands: X, Y and Z (right).

Enhanced Graph Representations of Chromatin Interaction Networks

581

2.2 Data Sets Used

We have analysed statistical properties of distribu-

tions of these edge directionality and strand location

patterns for two datasets of promoter capture Hi-C

(PCHi-C) data.

One of the best-suited datasets available for such a

purpose is the data set of long-range interactions be-

tween promoters and other regulatory elements that

were generated by The Babraham Institute and Uni-

versity of Cambridge (Javierre et al., 2016). This

data set is still largely unique because it contains

genome-wide data covering a representative subset

of the entire haematopoietic lineage collected using

a unified protocol. The data was obtained by pro-

moter capture Hi-C (PCHi-C) in 17 human primary

haematopoietic cell types, and from 31253 identified

promoter interaction regions across all chromosomes,

a subset of high-confidence PCHi-C interactions have

been selected using CHiCAGO pipeline (Cairns et al.,

2016). The graphs defining PCHi-C networks were

constructed using the same significance score of de-

tected interaction that was proposed in the dataset

analysed here. We use the same threshold that was

proposed in (Javierre et al., 2016) – i.e., interactions

with a significance score 5 or above were selected

for defining graph edges. Depending on the chromo-

some, the number of graph vertices ranges between

3000 and 23000 and the number of edges ranges be-

tween 8000 and 66000. We refer to this dataset as

Haema17.

The other well-curated promoter capture Hi-C

dataset (Jung et al., 2019) that we have used contains

data of 28 human tissue samples with an average of

9000 nodes and 17000 interactions per chromosome’s

tissue sample (when filtered by the suggested p-value

threshold p ≥ 0.7). Due to longer-range interactions

being considered less reliable, the authors have in-

cluded in their data only interactions with lengths not

exceeding 2Mb (which, unfortunately, is a limitation

from our perspective). We refer to this dataset as Tis-

sue28.

The average graph densities are similar for both

datasets and range between 2 and 3 depending on

the chromosome if cell type or tissue specificity of

the edges are not taken into account. The number of

edges shared by several cell lines or tissues, however,

is slightly higher in Haema17 dataset; this well cor-

responds to the fact that the Haema17 contains data

for more closely related cell types in comparison to

Tissue28.

Only interactions within the same chromosomes

are included in graphs defined by these datasets (thus,

each chromosome is represented separately by its spe-

cific graph). Chromosomes X and Y are not included

in the analysis. The edge directionally used to define

A, B, C and D types of 3-clique patterns are directly

based on ’bait’ and ’other end’ assignments as given

in PCHi-C data sets. Strand assignments for defining

X, Y and Z types of patterns were derived from strand

assignments of promoter regions according to the En-

sembl reference genome (GRCh38). Not all strand

assignments could be derived in such a way, and a

number of derived assignments were ambiguous. The

corresponding chromatin interactions in these cases

were excluded from datasets, resulting in the exclu-

sion of approximately 50% of interactions.

3 RESULTS

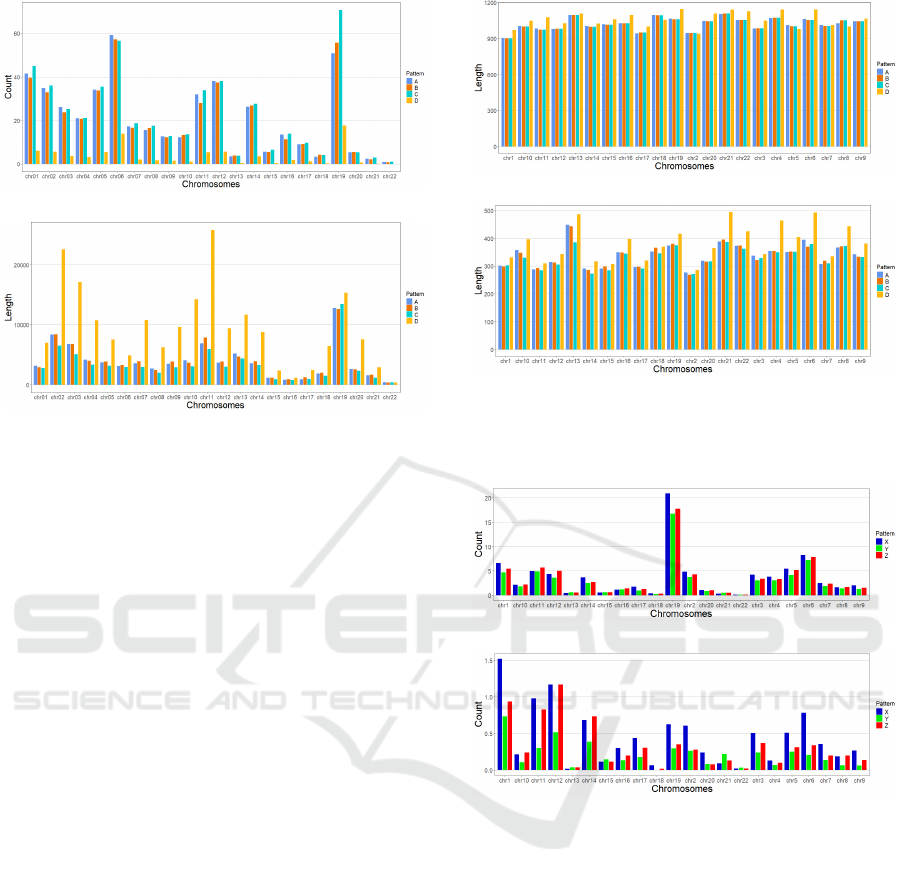

We have analysed statistical properties of distribu-

tions of edge directionality and strand location pat-

terns for Haema17 and Tissue28 data sets. Figure 2

shows the distribution of pattern A, B, C and D fre-

quencies (as counted in thousands) for each of the

chromosomes and also their average lengths (in kilo-

bases) for Haema17 data set. As it was anticipated,

there are no significant distinctions of pattern A, B

and C frequencies (466119 type A, 457752 type B

and 500289 type C patterns across the all chromo-

somes). Also, as it was anticipated, pattern D is less

abundant (81287 type D patterns across all the chro-

mosomes), although there is a notable variation in its

relative frequency by chromosomes. Very noticeably,

however, span lengths for type D patterns are signif-

icantly larger, indicating that their occurrence is not

distributed randomly – the average span lengths of

type A, B and C patterns being around 80Mb, and the

average span length of type D patterns around 205Mb.

Also worth noticing is the fact that the average length

increase for type D patterns is less pronounced for

chromosomes in which they occur more frequently

(e.g., for chromosomes 6 and 19, which have, corre-

spondingly, the average lengths around 30Mb and 130

Mb for the A, B and C types and the average lengths

around 50Mb and 150 Mb for the D type).

Unfortunately, Tissue28 data set does not allow to

replicate or validate the observation of substantially

increased span lengths of type D patterns since longer

range interactions have been explicitly excluded from

it.

At the present stage we can not provide a plausi-

ble biological explanation for increased span lengths

of type D patterns, although the observed increase of

lengths is statistically significant and likely must have

underlying reasons that merit further exploration.

A property that is shared by both datasets is the

BIOINFORMATICS 2025 - 16th International Conference on Bioinformatics Models, Methods and Algorithms

582

Figure 2: Counts (in thousands) of A, B, C and D type pat-

terns (above), and their average span lengths (in kb) (below)

for Haema17 dataset.

reduction of span lengths for all types of patterns

that are present in a larger number of tissues or cell

types. Figure 3 shows a comparison of average pat-

tern lengths in Tissue28 data set for unrestricted pat-

terns and patterns that occur in at least 5 different tis-

sue types – for the latter, the average span lengths drop

more than twice. Very similar approximately twofold

size reduction can be observed for Haema17 data set

(for cut-off using the same requirement, that patterns

must be shared by at least 5 different cell types), al-

though in numerical terms, the average span lengths

for this data set are larger. It should be noted that

this reduction of span lengths can not be explained by

reduced span lengths of single interactions shared by

multiple tissue or cell types, average lengths of which

depend little on the number of tissue or cell types in

which a particular interaction is observed.

The frequencies of X, Y and Z type patterns ob-

served in the whole data sets generally correspond to

random expectations, with similar counts of types X

and Y and type Z patterns being approximately twice

as frequent. For Haema17 data set, their frequency

distribution is shown in Figure 4 (above). (For eas-

ier comparison, the counts of Z types of patterns are

divided by 2.) The frequency distribution, however,

noticeably changes when we restrict our attention to

patterns with limited span lengths. In this case, a no-

ticeable increase in pattern X frequencies, as well as

a noticeable decrease in pattern Y frequencies, can be

observed. The results for Haema17 data set using 200

kilobase length cut-off is shown in Figure 4 (below).

Very similar results of X, Y and Z type pattern distri-

bution can be observed also for Tissue28 data set.

Figure 3: Average span lengths (in kb) of A, B, C and D

type patterns without tissue type specificity (above), and for

patterns that occur in at least 5 different tissues (below) for

Tissue28 dataset.

Figure 4: Counts (in thousands) of X, Y and Z type patterns

with unrestricted lengths (above), and with lengths up to

200kb (below) for Haema17 data set. For easier comparison

the counts of Z type patterns are divided by 2.

4 DISCUSSION

We have proposed an extension of graph represen-

tations of chromatin interaction networks by incor-

porating edge directionality and vertex label assign-

ments and have analysed statistical properties of dis-

tributions of patterns defined by edge directional-

ity (types A, B, C and D) and strand assignments

(types X, Y and Z) in well-curated two promoter cap-

ture Hi-C data sets. The results confirm that both

directionality- and strand-based patterns are not ran-

domly distributed, and there should be underlying bi-

ological reasons for the observed deviations.

One of the observed deviations is significantly in-

Enhanced Graph Representations of Chromatin Interaction Networks

583

creased span lengths of type D patterns, which are de-

fined by three promoters (in comparison, A, B and

C types of patterns involve only two promoters). A

possible explanation for this might be that, compared

to other types, the observed type D patterns can be

more likely associated with functioning gene regula-

tory feedback loops. Such a hypothesis could be val-

idated from gene expression measurements. Unfortu-

nately, no appropriate gene expression data with good

genome-wide coverage are available for cell types

from Haema17 data set. Similar validation would

be much easier to perform for Tissue28 data set us-

ing, e.g., gene expression data from GTEx consortium

(Consortium, 2020). However, the long-span chro-

matin interactions for which to perform such valida-

tions have not been included in the underlying PCHi-

C data. Nevertheless, there is a good potential to val-

idate or refute such a hypothesis when new, better-

suited experimental data sets become available. Pro-

vided that appropriate datasets for such type of analy-

sis is at hand, an interesting and promising challenge

in this research direction would be integrated analy-

sis of chromatin interaction and gene expression net-

works using a unified approach already well estab-

lished for gene expression networks, such as (Song

and Zhang, 2015).

The observation that for all types of patterns, their

average span lengths are reduced for patterns that are

present in a larger number of tissues or cell types is

consistent and complements a previously known fact

of tissue specificity of 3-cliques. The underlying rea-

sons for this merit additional exploration; however,

any pattern-type specificity for this property is lack-

ing.

Of notable interest might be the observed bias of

X, Y and Z pattern distributions for shorter-range in-

teractions. The most abundant type X patterns involve

all promoters positioned on the same strand, and the

least frequent type Y involves all adjacent promoters

lying on alternate strands. Thus, a plausible explana-

tion for such a bias could be related to local spatial

constraints on chromosome 3D structure, although a

much more detailed and comprehensive study would

be needed to assess this.

The observed statistical biases of 3-clique pattern

distribution are based on analysis of two PCHi-C data

sets and it remains an open question of how general-

izable or data set-specific these statistical deviations

could be. We also do not anticipate that any particular

type of the proposed patterns can be closely related

to some very specific biological role. Nevertheless,

the analysis gives a good justification for a further,

more comprehensive exploration of chromatin inter-

action data sets using network representations that in-

clude edge directionality and strand-based node la-

bel assignments, if these can be assigned on the basis

of the available data, and indicates a possibility that

these features might be related to some underlying bi-

ological mechanisms.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research was supported by Latvian Council of

Science project lzp-2021/1-0236.

REFERENCES

Cairns, J.and Freire-Pritchett, P. et al. (2016). CHiCAGO:

robust detection of DNA looping interactions in cap-

ture Hi-C data. Genome Biology, 17:127.

Catarino, R. and Stark, A. (2018). Assessing sufficiency

and necessity of enhancer activities for gene expres-

sion and the mechanisms of transcription activation.

Genes & Development, 32(3-4):202–223.

Consortium, G. (2020). The GTEx Consortium atlas of ge-

netic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science,

369(6509):1318–1330.

Dixon, J., Selvaraj, S., et al. (2012). Topological domains

in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chro-

matin interactions. Nature, 485:376–380.

Dotson, G., Chen, C., et al. (2022). Deciphering multi-way

interactions in the human genome. Nature Communi-

cations, 13:5498.

Eagen, K. (2018). Principles of chromosome architecture

revealed by Hi-C. Trends in Biochemical Sciences,

43(6):469–478.

Grubert, F., Srivas, R., et al. (2020). Landscape of cohesin-

mediated chromatin loops in the human genome. Na-

ture, 583(7818):737–743.

Javierre, B. Burre, O. et al. (2016). Lineage-specific

genome architecture links enhancers and non-coding

disease variants to target gene promoters. Cell,

167(5):1369–1384.

Jung, I., Schmitt, A., et al. (2019). A compendium of

promoter-centered long-range chromatin interactions

in the human genome. Nature Genetics, 51(10):1442–

1449.

Lace, L., Melkus, G., et al. (2020). Characteristic topo-

logical features of promoter capture Hi-C interaction

networks. Communications in Computer and Infor-

mation Science, 1211:192–215.

Lieberman-Aiden, E., Van Berkum, N., et al. (2009). Com-

prehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals

folding principles of the human genome. Science,

326(5950):289–293.

Matharu, N. and Ahituv, N. (2015). Minor loops

in major folds: Enhancer–promoter looping, chro-

matin restructuring, and their association with tran-

scriptional regulation and disease. PLOS Genetics,

11(12):e1005640:476–486.

BIOINFORMATICS 2025 - 16th International Conference on Bioinformatics Models, Methods and Algorithms

584

Melkus, G., Silina, S., et al. (2023). Clique-based topo-

logical characterization of chromatin interaction hubs.

Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 14248:476–486.

Mora, A., Sandve, G., et al. (2016). In the loop: promoter-

enhancer interactions and bioinformatics. Briefings in

Bioinformatics, 17(6):980–995.

Morlot, J., Mozziconacci, J., et al. (2016). Network con-

cepts for analyzing 3D genome structure from chro-

mosomal contact maps. PJ Nonlinear Biomedical

Physics, 4:2.

Pancaldi, V. (2023). Network models of chromatin struc-

tures. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development,

80:102051.

Przulj, N. and Malod-Dognin, N. (2016). Network analytics

in the age of big data. Science, 353(6295):123–124.

Rao, S., Huntley, M., et al. (2014). A 3D map of the hu-

man genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles

of chromatin looping. Cell, 162(3):687–688.

Sarajlic, A., Malod-Dognin, N., et al. (2016). Graphlet-

based characterization of directed networks. Scientific

Reports, 6(35098).

Schleif, R. (1992). DNA looping. Annual Review of Bio-

chemistry, 61:199–223.

Schmitt, A., Hu, M., et al. (2016). A compendium of chro-

matin contact maps reveal spatially active regions in

the human genome. Cell Reports, 17(8):2042–2059.

Schoenfelder, S., Clay, I., et al. (2010). The transcriptional

interactome: gene expression in 3D. Current Opinion

in Genetics & Development, 20(2):127–133.

Schulz, T., Stoye, J., et al. (2018). GraphTeams. a method

for discovering spatial gene clusters in hi-c sequenc-

ing data. BMC Genomics, 19(S5):308.

Siahpirani, A., Ferhat, A., et al. (2016). A multi-task

graph-clustering approach for chromosome conforma-

tion capture data sets identifies conserved modules of

chromosomal interactions. Genome Biology, 17:114.

Song, W. and Zhang, B. (2015). Multiscale embedded gene

co-expression network analysis. PLoS Computational

Biology, 11(11):e1004574.

Tan, Z., Guarnera, E., et al. (2018). Exploring chromatin

hierarchical organization via Markov State Modelling.

PLOS Computational Biology, 14(12):e1006686.

Thibodeau, A., Marquez, E., et al. (2017). Chromatin inter-

action networks revealed unique connectivity patterns

of broad H3K4me3 domains and super enhancers in

3D chromatin. Scientific Reports, 7(1):14466.

Viksna, J., Melkus, G., et al. (2020). Topological struc-

ture analysis of chromatin interaction networks. BMC

Bioinformatics, 20(S23):618.

Wang, W., Gao, L., et al. (2021). Ccip: predicting ctcf-

mediated chromatin loops with transitivity. Bioinfor-

matics, 37(24):4635–4642.

Yaveroglu, O., Milenkovic, T., and Przulj, N. (2015).

Proper evaluation of alignment-free network compar-

ison methods. Bioinformatics, 31(16):2697–2704.

Enhanced Graph Representations of Chromatin Interaction Networks

585