Exploring the Relationship Between Intracavitary Electrohysterogram

Characteristics from Contraction and Window Analysis

Juan Miguel Mira-Tomas

1a

, Alba Diaz-Martinez

1b

, Jose Alberola-Rubio

1c

, Pilar Alamá Faubel

2d

,

Gemma Castillón Cortés

2e

, Sergio Caballero Sanz

2f

and Javier Garcia-Casado

3g

1

SONDA DEVICES S.L, Valencia, Spain

2

Instituto Valenciano de Infertilidad (IVI), Valencia, Spain

3

Centro de Investigación e Innovación en Bioingeniería, Universitat Politècnica de València, Ci2B UPV, Valencia, Spain

Keywords: Intracavitary Electrohysterography, Contraction Analysis, Window Analysis, Uterine Peristalsis.

Abstract: Assisted reproductive technologies are increasingly common due to the rising maternal age. One potential

cause of embryo implantation failure is altered uterine peristalsis patterns. Intracavitary electrohysterography

(IC-EHG) is a recent technique developed to characterize the electrophysiology of uterine peristalsis

throughout the menstrual cycle. Two primary methodologies are employed for analysis: Contraction Analysis

and Window Analysis. This study aims to examine the relationship between parameters describing the same

characteristics of the signals using contraction and window analysis of 2, 4 and 10 minutes. Peristalsis was

recorded at three different menstrual cycle phases from 10 fertile healthy women. Continuous 10 minutes

recordings free of artifacts were selected. A very strong linear relationship (R

2

≥ 0.95) was found between the

amplitude parameter from contraction (Root Mean Square (RMS)) and window (80

th

percentile of signal RMS

envelope) analysis. For the spectral parameter (Median Frequency), the relationship was strong (0.59 ≤ R

2

≤

0.75), while for the non-linear parameter (Sample Entropy), it was moderate (0.19 ≤ R

2

≤ 0.29). Strongest

relationships were obtained with 2-minutes windows. The findings suggest that window analysis can

accurately assess contraction intensity and, more moderately its spectral content; but basal segments in

window analysis significantly influence the signal complexity parameter.

1 INTRODUCTION

The increasing maternal age in recent decades has led

to a raise in infertility rates, often needing assisted

reproductive technologies (Balasch, 2010).

Congenital and acquired uterine anomalies, such as

septate uterus or leiomyomas, are the most

contributing factor in approximately 30 % of

infertility cases (Brugo-Olmedo et al., 2001).

Endometriosis and adenomyosis are closely related

with infertility, since the appearance of endometrial

tissue in atypical places alter the normal anatomy of

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-7899-4864

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4605-6048

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2112-7927

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0204-0826

e

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-0558-0421

f

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1020-0239

g

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1410-2721

the uterine tract. These uterine pathologies express a

disturbed peristaltic pattern, since there exists a

significant increase in the number and power of

contractions (Leyendecker et al., 2022), which can

further complicate reproductive outcomes by

interfering with both sperm ascent and embryo

implantation.

Therefore, studying and characterizing uterine

peristalsis is crucial for developing effective therapies

for reproductive disorders associated with abnormal

uterine dynamics. Various techniques can be

employed to monitor uterine contractions throughout

914

Mira-Tomas, J. M., Diaz-Martinez, A., Alberola-Rubio, J., Faubel, P. A., Cortés, G. C., Sanz, S. C. and Garcia-Casado, J.

Exploring the Relationship Between Intracavitary Electrohysterogram Characteristics from Contraction and Window Analysis.

DOI: 10.5220/0013174000003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 1, pages 914-920

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

the menstrual cycle. Intrauterine pressure (IUP)

measurements are useful for obtaining mechanical

parameters such as contraction frequency of

occurrence, duration and amplitude (Benalcazar-

Parra et al., 2019). However, this method does not

provide information about spectral and nonlinear

domain parameters, as well as may not be sensitive

enough to capture low-intensity contractions that

occur during the menstrual cycle. Imaging-based

techniques such as transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS)

or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), can visualize

waves propagating throughout the endometrium by

watching video files at accelerated speed. In addition

to requiring expert operator and the subjectiveness of

the evaluation, the limitation of these techniques is

that they can only characterize the frequency of

occurrence and directionality of contractions, without

obtaining intrinsic contraction parameters (van Gestel

et al., 2007), (Togashi, 2007). All of these techniques

have been used to monitor uterine contractions during

menstrual cycle, as well as during pregnancy and

childbirth. Nevertheless, another technique known as

electrohisterography (EHG), allows the measurement

of myometrial electrical activity from the abdominal

surface during pregnancy (Diaz-Martinez et al., 2024)

and childbirth (Alberola-Rubio et al., 2017).

Intracavitary electrohysterography (IC-EHG)

emerged due to the need to study the

electrophysiology of low intensity uterine peristalsis

during the menstrual cycle (Alberola Rubio, 2021).

This technique enables the exploration of all

parameters assessed by the previous techniques, in

addition to those in the spectral and nonlinear

domains.

When characterizing myometrial electrical

activity using EHG, two primary approaches can be

followed: window analysis (WND) or contraction

analysis (CTR) (Díaz-Martinez et al., 2021), (Mas-

Cabo et al., 2019). In the former, fixed-length

segments are selected to encompass continously

physiological information from the signal. It is crucial

to ensure that these segments are free from artifacts

or interference that could distort parameter

calculations. Conversely, in contraction analysis,

parameters are computed over the signal bursts,

requiring prior identification of these contractions,

often a manual, subjective and time-consuming task

(Mas-Cabo et al., 2019).

The aim of this study is to investigate the degree

of association between parameters characterizing the

same characteristics of IC-EHG signals when using

either CTR or WND analysis.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Database Composition

This study included 30 IC-EHG signals acquired from

10 volunteer women at the Ovodonation Unit of the

Valencian Infertility Institute from Valencia, Madrid

and Barcelona. Participants of reproductive age (18-

34 years) were recruited if they exhibited regular

menstrual cycles, a body mass index between 18.5

and 25 kg/m², and a documented history of fertility.

Exclusion criteria included uterine malformations,

pregnancy, sexual intercourse within the previous 48

hours, use of any contraceptive method, severe

dysmenorrhea, irritable bowel syndrome, or a history

of ectopic pregnancies.

Following enrollment, each participant

underwent three recordings: one during the mid-

follicular phase (MF, 6-8 days post-menses), another

during the early luteal phase (EL, 2-4 days post-LH

surge), and a final one during the late-luteal phase

(LL, 7-9 days post-LH surge). All participants were

provided with detailed information about the study

and gave their informed consent. The study adhered

to the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of

Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional

Review Board of the Hospital Universitari i

Politècnic La Fe (Valencia, Spain) under registration

number 2023-108-1.

2.2 Signal Recording and Preprocessing

All recordings were conducted using a disposable 6-

pole multipolar catheter for the detection of non-

pregnant myometrial electrical activity (Alberola

Rubio, 2021). The tip electrode was in contact with

the uterine fundus, while the distal electrode was

closer to the cervix. The later served as the reference

electrode as smooth muscle cells content decreases

towards the cervix (Wray & Prendergast, n.d.).

Monopolar signals from each electrode were

amplified with a bandwidth of 0.1 to 30 Hz and

acquired for 30 minutes at a sampling rate of 500 Hz.

For this study, a bipolar signal from the uterine

fundus region was obtained as the difference between

the signals capturated by the first two catheter

electrodes. The signal was digitally filtered in the fast

wave bandwidth (Devedeux et al., 1993), (Fele-Žorž

et al., 2008). For each recording, a segment of 10

minutes of continous physiological information was

carefully selected by consensus between two experts,

avoiding artefacted signal segments

Exploring the Relationship Between Intracavitary Electrohysterogram Characteristics from Contraction and Window Analysis

915

Figure 1: Signal analysis methodology. A) Windowing step with CTR and WND analysis. Contractions have been identified

in CTR, whereas three different window sizes (10, 4 and 2 minutes) have been used in WND analysis. B) Amplitude, spectrum

and complexity parameter calculation for each analysis. C) Simple linear regression for assessing the relationship between

the same IC-EHG characteristics with CTR and WND analysis.

2.3 Windowing and Parametrization

Figure 1 illustrates the methodology employed in this

study. Initially, a windowing step is implemented to

identify the segments for analysis based on CTR o

WND approaches. Subsequently, parameters are

extracted from these segments and summarized at a

recording level by their median value. Finally, a

simple linear regression is performed for parameters

that characterize same IC-EHG features with CTR

and WND analysis.

As represented in Figure 1A, CTR analysis

requires the identification of the start and end points

of peristaltic waves. This was carried out by two

experts in electrohysterographic recording and

analysis. For each identified contraction, three widely

used parameters were calculated to describe different

aspects of the signal: signal amplitude/intensity,

spectrum and complexity.

Root Mean Square (RMS

CTR

): is a robust

measure for characterizing the intensity of the

uterine myoelectrical activity. It is defined as

the square root of the arithmetic mean of the

squares of the values (Mohammadi Far et al.,

2022).

Mean Frequency (MNF

CTR

): is a spectral

parameter related with cell excitability (Mas-

Cabo et al., 2020). It is computed as the sum of

product of the IC-EHG power spectrum and the

frequency divided by the total sum of the power

spectrum (Phinyomark et al., 2012).

Sample Entropy (SampEn

CTR

): is a non-

linear parameter which estimates signal

complexity. It is computed as the negative

natural logarithm of the probability that two

sequences similar for m points remain similar

at the next point, with a certain tolerance r and

ignoring self-matches. Hyperparameters m=2

and r=0.1 have been chosen as suggested in

(Radomski, 2010).

On the other hand, the WND analysis does not

require precise identification of peristaltic events but

does necessitate the setting of a hyperparameter, the

window size. In this study, three window sizes were

tested: 10, 4, and 2 minutes, with a 50% overlap

(except for 10 minutes windows), represented by

arrows of different color in Figure 1A. The following

parameters were computed for each window of

analysis.

To describe the intensity of the uterine

myoelectric activity, it is common to create an

envelope signal to analyze and characterize amplitude

evolution of EHG signals (Chowdhury et al., 2024).

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

916

It was calculated using a 5-second moving RMS,

computed sample by sample. Following the

generation of this smoothed version, the 80

th

percentile of the envelope weas selected for each

window (envP80

WND

). This selection was based on a

percentile sweep conducted with a step size of 5%,

identifying the percentile that exhibited the strongest

linear relationship with RMS

CTR

. MNF

WND

and

SampEn

WND

were computed as in the contraction

analysis, but on whole windows of the signal rather

than on single contractions.

To summarize the information at the recording

level, the median values of the contractions or

window’s parameters were calculated for each

analysis as represented in Figure 1B.

2.4 Variable Association

A simple linear regression model was used to assess

the relationship between the parameters derived from

CTR and WND analysis that characterized the signal

intensity, spectrum and complexity. The coefficient

of determination (R

2

) was computed to quantify the

proportion of variance in the dependent variable that

could be attributed to the predictor variable. This

metric provides an indication of the strength of the

linear association between the two variables, and it is

the evaluation metric selected as shown in Figure 1C.

3 RESULTS

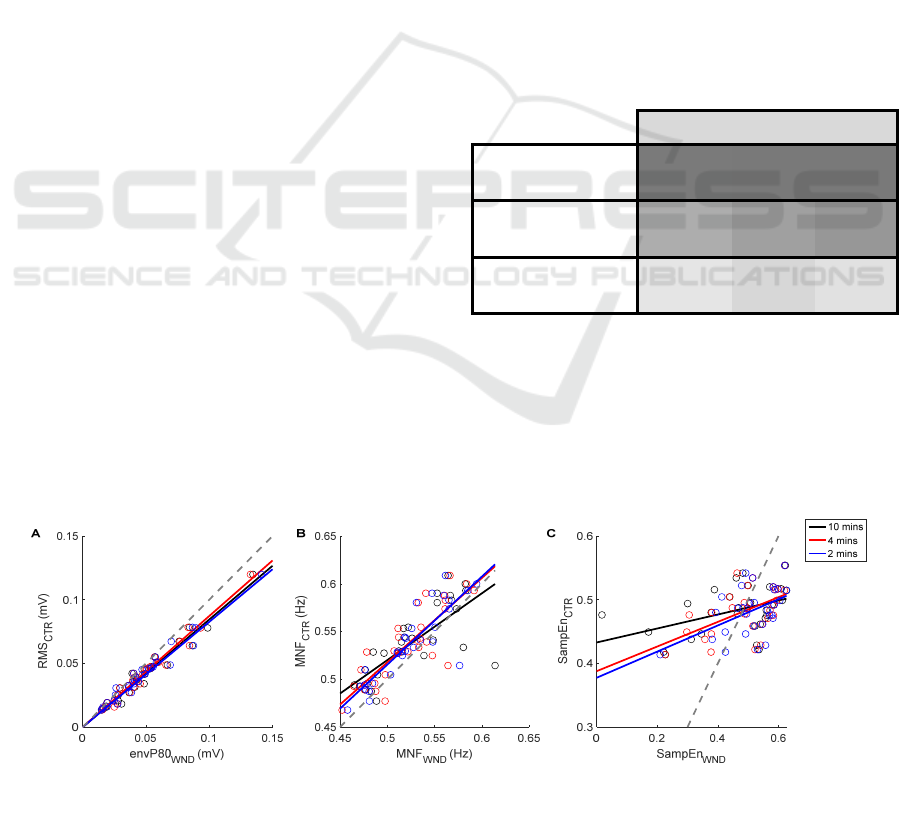

Figure 2 shows the scatterplots and linear

interpolation curves between contractions parameters

and their counterparts with window analysis using

different window sizes. Complementarily, Table 1

shows the coefficient of determination (R

2

) that

quantifies the strength of the linear relationship

between variables. Regarding amplitude parameters,

a very strong linear association (R

2

>0.95) was

obtained between RMS

CTR

and envP80

WND

for any

window size as observed in Table 1. Moreover, as it

can be appreciated in Figure 2A, the fitted lines for

the three window sizes show intercepts close to zero

and slopes slightly smaller than 1. Frequency domain

parameters MNF

CTR

and MNF

WND

also showed a

strong linear relationship between them. The

maximum R

2

is obtained when using a window size

of 2 minutes (R

2

=0.75), followed by the 4-min

window size (R

2

=0.69). The strength of the

relationship is s significantly reduced with a 10-min

window size (R

2

=0.59). Finally, complexity

parameters SampEn

CTR

and SampEn

WND

show a weak

relationship when using 10-min windows (R

2

=0.19),

and moderate for 2-min and 4-min windows (R

2

=0.22

and 0.29, respectively). This can also be seen in

Figure 2C, where it can be observed that the different

measurements are quite scattered without being

concentrated near the fit lines.

Table 1: Coefficients of determination (R

2

) of associations

between contraction and window analysis parameters using

different window sizes.

10 min 4 min 2 min

RMS

CTR

vs

envP80

WND

0.96 0.97 0.97

MNF

CTR

vs

MNF

WND

0.59 0.69 0.75

SampEn

CTR

vs

SampEn

WND

0.19 0.29 0.22

Moreover, to assess the effect of menstrual phase in the

analysis, same procedure has been carried out but

splitting the population into 3 different subpopulations

(MF, EL and LL), so that 10 recordings are analysed

for each group. Table 2 shows the strength of

association between same CTR and WND parameters

depending on each menstrual phase.

Figure 2: Scatterplot showing simple linear regression for the association between CTR and WND parameters when computed

using different window sizes. Dashed line represents 1:1 relationship (identity).

Exploring the Relationship Between Intracavitary Electrohysterogram Characteristics from Contraction and Window Analysis

917

Table 2: Coefficients of determination (R

2

) of associations

between CTR and WND parameters in subpopulations

based on menstrual phase (MF: mid follicular, EL: early

luteal, LL: late luteal).

10 min 4 min 2min

RMS

CTR

vs

envP80

WND

MF 0.95 0.95 0.94

EL 0.95 0.97 0.99

LL 0.92 0.93 0.95

MNF

CTR

vs

MNF

WND

MF 0.92 0.91 0.92

EL 0.21 0.49 0.56

LL 0.77 0.54 0.81

SampEn

CTR

vs

SampEn

WND

MF 0.55 0.56 0.55

EL 0.23 0.51 0.46

LL 0.08 0.12 0.12

It can be appreciated from Table 2 that amplitude

parameters are highly correlated irrespective of the

menstrual phase. However, some differences can be

appreciated in frequency and non-linear parameters

with respect to the menstrual phase. MNF

WND

in early

luteal phase do not correlate with MNF

CTR

as in MF

or LL. Similarly, SampEn

WND

and SampEn

CTR

do not

show linear correlation when assessed in LL.

4 DISCUSION

As shown in Table 1, there is a strong correlation

between amplitude parameters from contraction and

window analysis. The window size for the WND

analysis does not affect the strength of this

association. Nevertheless, we believe it is preferable

to use small window values, as spurious artifacts

might appear and, by selecting the median

envP80

WND

value across all windows, the analysis

could be more robust to outliers caused by high-

energy artifacts (Batista et al., 2016). According to

Table 2, the menstrual phase does not influence the

correlation between these two variables. While the

intensity of uterine contractions varies throughout the

menstrual cycle (Bulletti et al., 2004) under the

influence of sexual hormones, the association

between the two variables is robust to the influence of

the cycle phase. Therefore, the coefficients of the

simple linear regression could be used to predict the

RMS

CTR

parameter without the need for prior

segmentation of peristaltic contractions.

Regarding the spectral parameters MNF

CTR

and

MNF

WND

, there is a significant relationship between

them. Generally, MNF

CTR

values are higher than

MNF

WND

values (they lie above the identity line,

Figure 2B). This should mainly be associated to the

inclusion of basal segments in the calculation of

MNF

WND

. Basal segments are of lower power and

hence the power of the whole signal is reduced in

comparison to that of only contractions.

Consequently, the more concentrated power in the

lower frequencies of contraction segments is

emphasized with respect of this reduced total power,

yielding lower mean frequencies. Another aspect that

can provoke differences between MNF

CTR

and

MNF

WND

could be the difference in the frequency

resolution. As can be seen in Figure 1, the duration of

contractions is smaller than any window size (2, 4 or

10 mins), which modifies the frequency resolution for

CTR and WND analysis. The smallest window size

has the most similar frequency resolution to that of

contractions and could also be contributing to

obtaining the strongest relationship between spectral

parameters derived from CTR and WND analysis. It

is worth noting the low relationship between the two

parameters in EL phase in comparison to that of MF

phase. This could be related to differences in the

electrophysiological conditions of uterine muscle in

these two phases. More specifically, IUP recordings

during EL phase have shown a greater rate of

contractions and an elevated basal tone (Van Gestel

et al., 2003), which may be attributed to altered

cellular excitability in this phase, influencing the

basal state. Further studies would be necessary for a

more refined interpretation of these results.

Finally, a significant but moderate relationship

exists between SampEn

CTR

and SampEn

WND

. As

illustrated in Figure 2, it is preferable to use shorter

windows, of 2 or 4 minutes, as the regularity of the

signal may vary throughout the recording or differ

significantly between phases of the menstrual cycle,

making it challenging to generalize the relationship

between these variables across the entire menstrual

cycle. Physiologically, a decrease in entropy can be

interpreted as a result of increased coordination

among myometrial cells (Mischi et al., 2018). Similar

to findings regarding MNF, significant differences

have been observed between SampEn of contractile

and non-contractile segments in EHG recordings

from pregnant women (Hao et al., 2019). While the

behavior in non-pregnant uteri is not fully

understood, it is likely that coordination among cells

changes throughout the menstrual cycle for both

contractile and non-contractile segments. Table 2

supports this hypothesis, as the correlation between

SampEn

CTR

and SampEn

WND

decreases as the cycle

progresses, being much lower in the luteal phase than

the mid-follicular phase. This may be attributed to

changes in the expression of gap junctions throughout

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

918

the menstrual cycle. Estrogen, the dominant hormone

during the follicular phase, promotes the formation of

connexin 43 (the protein that makes up gap junctions,

which facilitate the electrical communication between

adjacent cells). In contrast, progesterone, which

dominates the luteal phase, reduces the expression of

connexin 43, leading to decreased cellular coordination

during this phase (Condon et al., 2020).

This study has several limitations. The

identification of the artefactual signal segments to be

excluded from the analysis is carried out manually by

two experts. In future studies, automatic classifiers

could be used to annotate artifacted segments.

To assess the degree of relationship between the

parameters derived from the WND and CTR

methods, the R2 of the linear regression was used. An

error analysis could provide additional information.

For example, a Bland-Altman plot would be

informative to identify and provide further insight

into the causes of those specific cases where a

significant deviation is observed between the

parameter calculated using the WND and CTR

methods. In addition, the sample size is small and it

would be necessary to expand the database and ensure

the reproducibility of the experiment by obtaining

multiple samples per subject and phase.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The IC-EHG technology has emerged as an

alternative technique for analyzing myometrial

electrophysiology in non-pregnant uteri. This

technique allows for the exploration of spectral and

non-linear parameters that have only previously been

examined in pregnant uteri through EHG recordings

on the abdominal surface. Two primary

methodologies have been used in this context: CTR

and WND analysis. This study aimed to investigate

the relationship between parameters that characterize

the same characteristics of the IC-EHG signal using

CTR and WND analysis to assess their estimation

without the need for cumbersome annotation of

contractions.

In terms of the amplitude, the parameters from

both methods are very highly correlated, indicating

that the envP80

WND

parameter could be used to assess

contraction intensity without prior segmentation,

regardless of the menstrual cycle phase. Regarding

the spectral content, associated to cell excitability, the

MNF of uterine contractions can also be accurately

inferred from whole window analysis, especially in

MF and LL phases. Nonetheless, the signal

complexity during contractions, associated to

coordination among cells, would be poorly inferred

without IC-EHG bursts identification.

Another important conclusion of this work is that,

although longer recordings are necessary to reduce

the possible variability between analysis windows,

the optimal window size for these calculations is 2

minutes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was funded and supported by the

Science and Innovation Ministry of Spain (DIN2021-

012073).

REFERENCES

Alberola Rubio, J. (2021). Probes, Systems and Methods

for Measuring and/or Characterizing Uterine Activity

in a Non-Pregnant Uterus. https://patentscope.

wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=WO2021185781

Alberola-Rubio, J., Garcia-Casado, J., Prats-Boluda, G.,

Ye-Lin, Y., Desantes, D., Valero, J., & Perales, A.

(2017). Prediction of labor onset type: Spontaneous vs

induced; role of electrohysterography? Computer

Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 144, 127–133.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2017.03.018

Balasch, J. (2010). Ageing and infertility: An overview.

Gynecological Endocrinology, 26(12), 855–860.

https://doi.org/10.3109/09513590.2010.501889

Batista, A. G., Najdi, S., Godinho, D. M., Martins, C.,

Serrano, F. C., Ortigueira, M. D., & Rato, R. T. (2016).

A multichannel time–frequency and multi-wavelet

toolbox for uterine electromyography processing and

visualisation. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 76,

178–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2016.

07.003

Benalcazar-Parra, C., Garcia-Casado, J., Ye-Lin, Y.,

Alberola-Rubio, J., Lopez, Á., Perales-Marin, A., &

Prats-Boluda, G. (2019). New electrohysterogram-

based estimators of intrauterine pressure signal, tonus

and contraction peak for non-invasive labor monitoring.

Physiological Measurement, 40(8), 085003.

https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6579/ab37db

Brugo-Olmedo, S., Chillik, C., & Kopelman, S. (2001).

Definition and causes of infertility. Reproductive

BioMedicine Online, 2(1), 173–185. https://doi.org/

10.1016/S1472-6483(10)62193-1

Bulletti, C., De Ziegler, D., Setti, P. L., Cicinelli, E., Polli,

V., & Flamigni, C. (2004). The Patterns of Uterine

Contractility in Normal Menstruating Women: From

Physiology to Pathology. Annals of the New York

Academy of Sciences, 1034(1), 64–83. https://doi.org/

10.1196/annals.1335.007

Chowdhury, R. H., Hossain, Q. D., & Ahmad, M. (2024).

Automated Method for Uterine Contraction Extraction

Exploring the Relationship Between Intracavitary Electrohysterogram Characteristics from Contraction and Window Analysis

919

and Classification of Term Versus Pre-Term EHG

Signals. IEEE Access, 12, 49363–49375. IEEE Access.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3384258

Condon, J. C., Kyathanahalli, C., Anamthathmakula, P., &

Jeyasuria, P. (2020). Estrogen/estrogen receptor action

and the pregnant myometrium. Current Opinion in

Physiology, 13, 135–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.cophys.2019.10.017

Devedeux, D., Marque, C., Mansour, S., Germain, G., &

Duchêne, J. (1993). Uterine electromyography: A

critical review. American Journal of Obstetrics &

Gynecology, 169(6), 1636–1653. https://doi.org/

10.1016/0002-9378(93)90456-S

Díaz-Martinez, A., Monfort-Ortiz, R., Ye-Lin, Y., Garcia-

Casado, J., Nieto-Del-Amor, F., Diago-Almela, V. J.,

Rey-Ferreira, I., Nieto-Tous, M., & Prats-Boluda, G.

(2021). Comparative Study of Uterine Myoelectrical

Response to Labour Induction Drugs in Nulliparous and

Parous Women with Different EHG Analysis

Techniques. 2021 International Conference on E-

Health and Bioengineering (EHB), 1–4.

https://doi.org/10.1109/EHB52898.2021.9657548

Diaz-Martinez, A., Prats-Boluda, G., Monfort-Ortiz, R.,

Garcia-Casado, J., Roca-Prats, A., Tormo-Crespo, E.,

Nieto-del-Amor, F., Diago-Almela, V.-J., & Ye-Lin, Y.

(2024). Overdistention Accelerates Electrophysiolo-

gical Changes in Uterine Muscle Towards Labour in

Multiple Gestations. IRBM, 45(3), 100837.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irbm.2024.100837

Fele-Žorž, G., Kavšek, G., Novak-Antolič, Ž., & Jager, F.

(2008). A comparison of various linear and non-linear

signal processing techniques to separate uterine EMG

records of term and pre-term delivery groups. Medical

& Biological Engineering & Computing, 46(9), 911–

922. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11517-008-0350-y

Hao, D., An, Y., Qiao, X., Qiu, Q., Zhou, X., & Peng, J.

(2019). Development of Electrohysterogram Recording

System for Monitoring Uterine Contraction. Journal of

Healthcare Engineering, 2019(1), 4230157.

https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/4230157

Leyendecker, G., Wildt, L., Laschke, M. W., & Mall, G.

(2022). Archimetrosis: The evolution of a disease and

its extant presentation: Pathogenesis and

pathophysiology of archimetrosis (uterine adenomyosis

and endometriosis). Archives of Gynecology and

Obstetrics, 307(1), 93–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/

s00404-022-06597-y

Mas-Cabo, J., Prats-Boluda, G., Perales, A., Garcia-

Casado, J., Alberola-Rubio, J., & Ye-Lin, Y. (2019).

Uterine electromyography for discrimination of labor

imminence in women with threatened preterm labor

under tocolytic treatment. Medical & Biological

Engineering & Computing, 57(2), 401–411.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11517-018-1888-y

Mas-Cabo, J., Ye-Lin, Y., Garcia-Casado, J., Díaz-

Martinez, A., Perales-Marin, A., Monfort-Ortiz, R.,

Roca-Prats, A., López-Corral, Á., & Prats-Boluda, G.

(2020). Robust Characterization of the Uterine

Myoelectrical Activity in Different Obstetric Scenarios.

Entropy, 22(7), Article 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/e220

70743

Mischi, M., Chen, C., Ignatenko, T., de Lau, H., Ding, B.,

Oei, S. G. G., & Rabotti, C. (2018). Dedicated Entropy

Measures for Early Assessment of Pregnancy

Progression From Single-Channel Electrohystero-

graphy. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering,

65(4), 875–884. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical

Engineering. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2017.2723

933

Mohammadi Far, S., Beiramvand, M., Shahbakhti, M., &

Augustyniak, P. (2022). Prediction of Preterm Delivery

from Unbalanced EHG Database. Sensors, 22(4),

Article 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22041507

Phinyomark, A., Thongpanja, S., Hu, H., Phukpattaranont,

P., Limsakul, C., Phinyomark, A., Thongpanja, S., Hu,

H., Phukpattaranont, P., & Limsakul, C. (2012). The

Usefulness of Mean and Median Frequencies in

Electromyography Analysis. In Computational

Intelligence in Electromyography Analysis—A

Perspective on Current Applications and Future

Challenges. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/50639

Radomski, D. (2010). Sensitivity analysis of a sample

entropy estimator on its parameters in application to

electrohysterographical signals. Biocybernetics and

Biomedical Engineering, Vol. 30, 2, 67–72.

Togashi, K. (2007). Uterine Contractility Evaluated on Cine

Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Annals of the New York

Academy of Sciences, 1101(1), 62–71. https://doi.org/

10.1196/annals.1389.030

van Gestel, I., IJland, M. M., Evers, J. L. H., & Hoogland,

H. J. (2007). Complex endometrial wave-patterns in

IVF. Fertility and Sterility, 88(3), 612–615.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.12.050

Van Gestel, I., IJland, M. M., Hoogland, H. J., & Evers, J.

L. H. (2003). Endometrial wave-like activity in the non-

pregnant uterus. Human Reproduction Update, 9(2),

131–138. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmg011

Wray, S., & Prendergast, C. P. (n.d.). The Myometrium:

From Excitation to Contractions and Labour. In Smooth

Muscle Spontaneous: Activity Physiological and

Pathological Modulation (Vol. 1124, pp. 233–263).

Springer International Publishing.

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

920