A Conceptual SOC Framework for Air Traffic Management Systems

Wesley Murisa

a

and Marijke Coetzee

b

School of Computer Science & Information Systems, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

Keywords: Security Operations Centre, Air Traffic Management, Aviation, SOC Framework.

Abstract: Air Traffic Management (ATM) systems were originally developed without incorporating essential security

controls such as confidentiality, integrity, and availability. Integrating external systems into ATM systems

has further heightened their vulnerability to cybersecurity threats. A Security Operations Centre (SOC) can

help mitigate these risks by offering threat visibility and facilitating incident response. However, the

successful implementation of a SOC in the aviation sector requires a framework tailored to its specific needs,

which is currently lacking in existing literature. This study addresses this gap by reviewing SOC frameworks

from other industries to identify foundational elements for an ATM-specific SOC framework. Key pillars—

People, Processes, Technology, Compliance, and Governance—common to SOCs across various sectors were

adapted to fit the distinctive requirements of ATM. The resulting conceptual framework consists of five core

components and three success factors, all designed to meet the unique cybersecurity demands of the aviation

sector.

1 INTRODUCTION

Air Traffic Management (ATM) systems face

increasing cybersecurity threats (Dave et al., 2022),

but unlike other industries, they lack a comprehensive

framework for implementing a Security Operations

Centre (SOC). SOCs enable organisations to comply

with legal and regulatory requirements by

continuously monitoring networks for security

threats, maintaining logs for extended periods, and

supporting forensic investigations (Jacobs et al.,

2013). Despite these benefits, SOCs are costly to

establish, and their effectiveness relies on proper

implementation, including the successful onboarding

of critical cyber assets and alignment with an

organisation's specific needs. Inadequate onboarding,

lack of executive support, and insufficient

cybersecurity personnel can lead to effective SOCs,

resulting in missed threats, alert fatigue, and a false

sense of security.

The ATM sector presents unique challenges that

differentiate it from other industries where SOC

frameworks have been proposed. ATM systems

consist predominantly of radio-based operational

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-5165-1862

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9157-3079

technology (OT) that is difficult to integrate into

traditional IT-centric SOCs. Additionally, many of

these systems rely on outdated technologies and

proprietary protocols, further complicating

integration efforts. Furthermore, International Civil

Aviation Organization (ICAO) regulations mandate

separating ATM systems from other networks,

creating additional barriers to SOC implementation.

A literature survey on SOC frameworks

conducted in this study revealed the absence of a SOC

framework in ATM systems. This paper addresses

this gap by proposing a high-level SOC framework

for the sector. To achieve this, ATM systems and

their functions are described in Section 2 before

outlining cybersecurity challenges in Section 3.

Section 4 describes SOCs and their functions and

highlights the progress in implementing them in ATM

systems. Section 5 describes the literature survey on

SOC frameworks and presents the results. An

assessment of SOC requirements for ATMs is

outlined in Section 6. Section 7 presents a conceptual

framework for implementing SOCs in ATM systems

before the conclusion in Section 8.

Murisa, W. and Coetzee, M.

A Conceptual SOC Framework for Air Traffic Management Systems.

DOI: 10.5220/0013174200003899

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2025) - Volume 1, pages 275-282

ISBN: 978-989-758-735-1; ISSN: 2184-4356

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

275

PSR SSR ADS-B

Aeronautical

Information Services

Meteorological

Services

Air Traffic Controller

Display System

VHF

CPDLC

WAM

VOR

ILS

DME

Aircraft

GNSS

Pilot

Air Traffic

Controller

Status

Monitoring

On prem IT systems

• HR systems

• Billing Systems

Cloud Systems

Online Storage

E-mails

Bring Your Own Device

(BYOD)

Smart phones

Tablets

Support &

Maintenance

Support &

Maintenance

Support &

Maintenance

Original Equipment

Manufacturer support

services

External systems

ATM Systems

Aircraft location

Communication

Communication

Navigation

Weather

Information

from other

airports

VHF out of range

Business systems

access & support

services

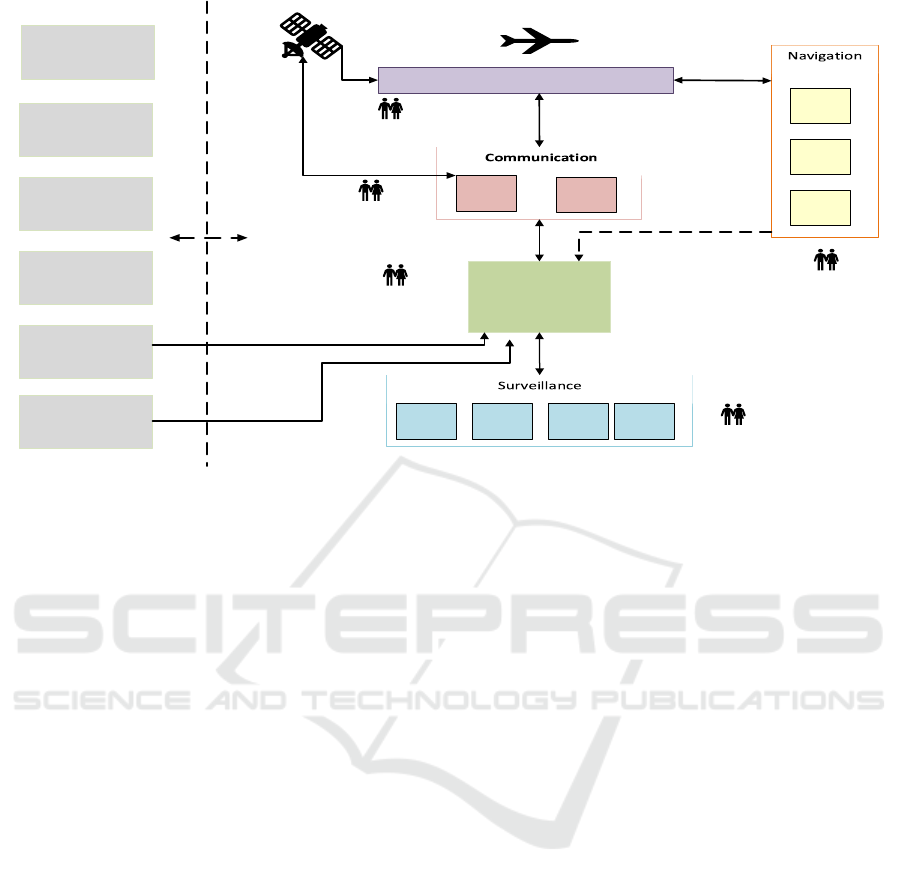

Figure 1: Air Traffic Management Systems.

2 AIR TRAFFIC MANAGEMENT

Air Navigation Service Providers (ANSPs) manage

air traffic from take-off, transit and landing. They use

ATM systems to communicate and monitor air traffic.

The primary objectives of ANSPs are to manage air

traffic flow and prevent aircraft collisions in the

airspace (Batuwangala et al., 2018). ATM

systems provide pilots with critical take-off, transit,

and landing information.

Air traffic control (ATC) is essential to air traffic

management (ATM) systems. Surveillance,

meteorological, aeronautical information, and

navigation systems data are collected, integrated and

displayed onto the ATC display system, as shown in

Figure 1. The Air traffic controllers (ATCOs)

communicate the information on the ATC Display

System to pilots using the communication system.

Apart from pilots and ATCOs, ATM engineers

play a critical support and maintenance role in the

ATM ecosystem. Internal engineers often get remote

assistance from Original Equipment Manufacturers

(OEM), typically via virtual private networks.

ATCOs and ATM engineers access on-premises and

cloud-based IT systems, such as human resources and

financial systems for administrative duties. These

systems include email and online data storage.

The systems on the left side of the dotted lines in

Figure 1 show the external systems that ATM systems

and ATM personnel interact with. Meteorological and

aeronautical information services are provided by

third parties outside the core ATM systems but

provide critical information that is regularly

communicated to pilots.

While local engineers maintain ATM systems,

remote support from Original Equipment

Manufacturers (OEM) may be needed, typically via a

virtual private network. Another external system that

interacts with ATM systems is the Bring Your Own

Device (BYOD) system, which allows personnel to

use smartphones and tablets for both business and

personal tasks, like accessing emails and documents.

The Global Navigation Satellite System (GNS)

provides location data for surveillance systems.

Communication, Navigation, and Surveillance

(CNS) systems are essential to ATM.

Communication systems are used for bidirectional

communication between ATCOs and pilots.

Navigation systems guide pilots during transit.

ATCOs use surveillance systems to monitor aircraft

positions and detect rogue planes.

CNS systems are vulnerable to cybersecurity

threats because security controls that provide for

Confidentiality, Integrity and Availability (CIA) were

not included in their designs (Dave et al., 2022).

While attempts are made to isolate ATM systems for

security, interaction with external systems is required.

Table 1 describes the current CNS systems and how

they fare against CIA cybersecurity principles.

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

276

Table 1: ATM systems cybersecurity challenges.

System Description Confidentiality Integrity Availability

Communication

Controller Pilot Data Link

Communication (CPDLC)

Text message communication between

ATC and pilots

X

X

X

Very High Frequency (VHF) Voice communication between ATC

and pilots

X

X

Navigation

Distance Measuring Equipment

(DME)

Measures the distance between the

aircraft and the ground station.

X X X

Global Navigation Satellite System

(GNSS)

Determine geographical position and

velocity

X X X

Instrument landing System (ILS) Guide aircraft during landing X X X

VHF omnidirectional range (VOR) Determine aircraft location X X X

Surveillance

Automatic Dependent

Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B)

Surveillance based on aircraft broadcast

messages.

X X X

Primary Surveillance Radar (PSR) Non-cooperative airspace surveillance X X

Secondary Surveillance Radar

(SSR)

Cooperative surveillance based on

interrogating aircraft for their position

X X X

Wide Area Multilateration (WAM) Surveillance based on multiple sensors

that overcome terrain obstructions.

X X X

3 SECURITY THREATS IN ATM

An ATM network is traditionally segregated from the

local area network, preventing unauthorised access.

However, today's technological landscape, which

includes cloud-based systems, BYOD, and IoT

devices, is complex to segregate. Such extended

networks connected to the Internet expose ATM

systems to cyber security threats. Therefore, threat

actors can remotely exploit vulnerabilities they could

not before. These vulnerabilities in ATM systems are

outlined below.

Jamming/ DoS

CNS systems such as VHF, CPDLP, ADS-B and SSR

that use radio frequency are susceptible to jamming.

Jamming occurs when a frequency band is

overwhelmed by radio devices using the same

frequency (Dave et al., 2022). As a result, legitimate

communication is disrupted, and communication

between an aircraft and the ground-based air traffic

control is disrupted, causing a denial-of-service

attack. SSR jamming has resulted in surveillance

failures in Europe (Strohmeier et al., 2020).

Eavesdropping

Eavesdropping refers to unauthorised access to radio

communication between ATC and pilots using a radio

transmitter-receiver antenna. All ATM systems

shown in Table 1 lack mechanisms to guarantee

confidentiality. A malicious entity with a radio

transmitter-receiver can intercept messages without

any authentication required. Eavesdropping can be

used to track the location of aircraft for malicious

purposes (Strohmeier et al., 2020).

Spoofing

An attacker with a readily available Software Defined

Radio (SDR) can impersonate legitimate aircraft by

generating and transmitting spoofed data (Osechas et

al., 2017). Incidents of spoofed communications have

been reported (Strohmeier et al., 2017). It was

reported that in typical cyberwarfare, a national army

hacked a civilian aviation communication system and

prevented an adversary's plane from landing

(Paganini, 2024).

Supply Chain Attack Vectors

Suppliers of ATM products and services, such as

equipment, software and hardware systems, are

potential attack vectors. Vendors are usually trusted

with physical and remote access to networks and

systems for support and maintenance (Kandera et al.,

2022). Threat actors can compromise a vendor and

use that access to target the vendor's clients. Systems

under development can also be compromised with

backdoors or malicious code before they are shipped

to clients. Attackers can obtain remote access through

those vulnerabilities.

Network Intrusion

Although isolated from IT networks, the data links

used to connect ATM systems do not use

A Conceptual SOC Framework for Air Traffic Management Systems

277

authentication and basic error-checking mechanisms

(Osechas et al., 2017). Message modifications and

spoofing cannot be detected. As shown in Figure 1,

the interconnection of these data links with IT

systems, cloud systems, and BYOD devices

connected to the Internet exposes ATM systems to

serious cybersecurity threats. Security breaches from

IT networks can affect ATM systems such as the ATC

Display System.

Legacy Systems

When most ATM systems were designed,

functionality was prioritised over security because

cybersecurity attacks were not a problem. For

example, PSR was developed during the World War

but is still actively used today. As a result, cheap and

readily available tools such as SDRs (Lu et al., 2023)

can easily exploit clear-text wireless communication

used in most ATM systems.

The International Civil Aviation Organization

(ICAO), which oversees global civil aviation and

ATM systems, addresses aviation cybersecurity

through its Global Air Navigation Plan, promoting

the development of secure ATM systems (ICAO,

2024). Other ANSPs and aviation stakeholders have

implemented SOCs to support incident response,

information sharing, and visibility of security threats

(Awadhi, 2023). Section four below describes SOCs

in detail.

4 SECURITY OPERATIONS

CENTRES

Security Operations Centres (SOCs) are business

functions that play a pivotal role in an organisation's

cyber security strategy. They provide cybersecurity

situational awareness by detecting security threats

(Jacobs et al., 2013). Apart from threat detection,

SOC enables organisations to comply with legal and

regulatory requirements to continuously monitor their

networks for security attacks and keep logs for

extended periods (Jacobs et al., 2013). They also

allow organisations to monitor system availability by

sending logs to the SIEM. Further, long-term storage

of security logs supports forensic and incident

response investigations. The uses of SOCs explained

above have made them a popular tool in many

organisations.

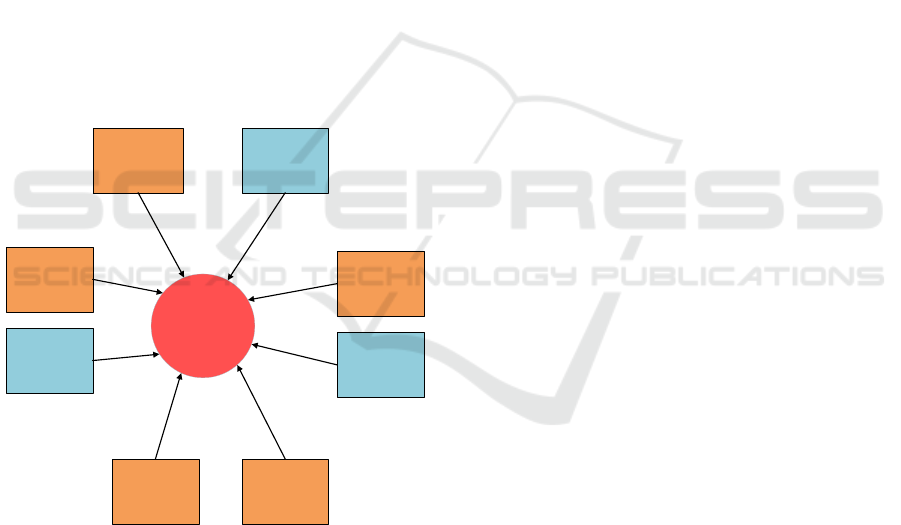

Figure 2 shows that SOCs collect security logs

from on-premises and cloud systems such as servers,

active directories, and applications. Logs are also

gathered from networking equipment and security

controls such as firewalls and antimalware systems

(Mutemwa et al., 2018). These logs are normalised,

correlated and stored in a Security Information and

Event Management (SIEM) solution. The SIEM

analyses the logs using threat intelligence, artificial

intelligence, and machine learning to detect security

attacks in the network, thereby providing much-

needed visibility of security threats targeting an

organisation.

Figure 2: Security Operations Centre.

Identified security threats are investigated and

remediated by SOC analysts (Mughal, 2022).

Detailed information on identified threats and how

they have been handled is usually displayed on the

SOC dashboard in addition to periodic reports, as

illustrated in Figure 2.

In response to increasing cybersecurity threats,

the ATM sector has started implementing SOCs.

Awadhi (2023) explained that despite ATM systems

being closed networks, the United Arab Emirates

implemented SOCs for real-time monitoring, attack

detection, and incident response support. The

European Air Traffic Management Computer

Emergency Response Team (EATM-CERT) and The

Aviation Information Sharing Centre (A-ISA) have

also implemented SOCs to support incident response

activities (Lekota & Coetzee, 2021).

Lastly, prominent aviation industry players

Boeing and Thales have established managed

Security Operations Centre services that provide

services to the aviation industry and beyond. These

two private companies are major players in the

aviation industry, meaning they possess specialised

domain knowledge that can provide better service

than other service providers not involved in the

aviation sector. However, they have not produced any

publicly available framework to guide the

implementation of SOCs in ATM systems. To

address this problem, section 5 investigates the

implementation of SOCs in aviation.

Alerts

Cloud

Infrastracture

Antivirus

Systems

Firewalls

• Servers

• Active Directory

• Routers

• Switches

Application

Servers

SIEM

• Normalisation

• Correlation

• Long term

storage

• Management

• CSIRT

• Forensic Specialists

• Threat hunting specialists

SOC Analysts

• Dashboard

• Reporting

• Threat Monitoring

Threat

Intelligence

• Artificial intelligence

• Machine Learning

• Incident detection

Auto

Remediation

Playbook

Collection of security logs

Identification of security attacks and threats

Security Monitoring and Remediation

Esca lation

Analysis

SECURITY OPERATIONS CENTRE

• Policies

• Standards

• benchmarks

Cyber Assets

Onboar ding

Threat identification

Triage, remediation, incident response

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

278

5 SOC FRAMEWORKS

Although SOCs have been acknowledged as valuable

tools for fighting increased cybersecurity attacks,

little has been done to produce SOC implementation

guidelines and frameworks. Several researchers have

responded to this research gap and created

frameworks for different domains. The authors

surveyed published literature on SOC frameworks to

find a guideline for implementing SOCs in ATMs.

The methodology used for the review is provided

below.

Table 2 lists the keywords used in the search for

relevant literature, including the keywords, databases,

and timeframes. Google Scholar, IEEE Xplore,

Science Direct, Scopus, and Web of Science were

selected for the search because of their popularity in

scientific research. Only open-access articles written

in English were considered for the study.

338 open-access articles met the search criteria in

Table 2. After importing the references in the

Convidence tool, 66 duplicates were removed, leaving

272 articles for initial screening. The initial screening

process based on title and abstract eliminated 240

articles, leaving 32 for full-text review. Only 10 articles

on SOC implementation frameworks remained after a

full-text review. Details of the relevant literature are

provided in the following paragraphs.

Table 2: Research methodology.

Research

Question

1. What has been published on SOC

frameworks?

2. What are the critical aspects of a SOC

implementation framework?

Search

Criteria

English Language, Title, abstract,

ke

y

words

Keywords Security Operations Centre OR Security

Operation Centre OR

Security Operations Center OR

Security Operation Center AND

framewor

k

Databases Google Scholar, IEEE Xplore, Science

Direct, Sco

p

us, Web of Science.

Inclusion

criteria

Literature outlining a general or domain-

specific SOC framework.

Date 2014 to 2024

The frameworks identified covered four domains:

smart cars, education, government, and unmanned

aerial vehicles (UAV). Although three studies

produced general frameworks that any organisation

can adopt, the other seven identified the need for a

customised SOC framework to suit a particular

domain's circumstances. Most authors agree on the

components of a SOC. People, Processes, and

Technology (PPT) are the standard SOC components

identified in eight out of ten studies in the literature.

However, two authors named Governance and

Compliance the fourth component. Majid and Ariffin

(2021) identified Top Management Support, Finance

and Continuous Improvement as additional critical

components.

People refer to those running a SOC, such as

management, consultants, and SOC analysts.

Analysts can be grouped into three tiers (Agyepong et

al.). Tier 1 SOC analysts are responsible for initial

incident triage and determining whether an alert is a

true or false positive. If they cannot solve an incident,

they escalate to more skilled and experienced analysts

in Tiers 2 and 3, where highly qualified specialists

like malware analysts, threat hunters and digital

forensics are found. Management includes the SOC

manager and top-level management, whose support is

essential for SOC success.

Processes refer to the policies and procedures for

managing the SOC's operations. They range from

service-level agreements for resolving alerts logged

in the call desk system to incident response policies

that guide incident management processes. Other

operational procedures, like the period that logs

should be stored in the SIEM, form part of the

processes that govern SOC operations

Technology refers to tools that perform various

tasks in a SOC. These include the SIEM, the SOC

engine that analyses logs and identifies security

threats and attacks. Other tools include security

controls, network devices that send logs to the SIEM,

vulnerability management systems, machine learning

algorithms, and dashboards. Majid and Ariffin (2021)

believes that technology is more important than the

other SOC components.

Governance and compliance relate to standards

and guidelines that ensure SOC efficiency and

effectiveness. Security audits, maturity assessments,

and SOC metrics are some of the activities that make

up governance. On the other hand, compliance

activities ensure that SOC operates according to

policy and best practice standards.

The motivating factor for most authors was the

absence of a SOC framework or implementation

guideline. Barletta et al. (2023) and (Han et al., 2023)

focused on technical components in the models for

smart cars. For UAVs, (Tlili et al., 2024) proposed

using artificial intelligence methods to detect and

prevent threats. Danquah (2020) produced a

generalised framework for incorporating artificial

intelligence methods to improve triage, containment

and escalation. Only (Schinagl et al., 2015) focus

more on people.

A Conceptual SOC Framework for Air Traffic Management Systems

279

A meaningful topic that has emerged from the

literature review is improving threat detection

through artificial intelligence methods. Tlili et al.

(2024) outlined how deep learning can be used to

detect spoofed GPS signals. Artificial intelligence

algorithms can also detect radio frequency jamming

and message injections. These methods can be

considered for radio frequency systems in air traffic

management.

Even though ATMs are specialised critical

infrastructures facing increased cybersecurity threats,

the literature does not include a SOC framework or

model for the sector. This calls for the development

of a customised framework for ATMs. The following

section lays out the first step towards that goal by

looking at the unique requirements for ATMs.

6 ATM SOC REQUIREMENTS

Considering an organisation's unique requirements is

one of the factors necessary for success in SOCs

(Vielberth et al.). A SOC framework that considers

ATM unique nature can address this research gap.

The following unique aspects should be considered

when designing a SOC framework for ATM systems.

Legacy Systems

Most ATM systems are legacy systems no longer

supported by modern systems, which presents a

challenge for onboarding to a SOC. Care should be

taken to ensure successful onboarding and preserve

the operational integrity of these systems. Challenges

with onboarding legacy systems to SOCs have been

reported in the maritime sector (Nganga et al., 2024).

Therefore OEMs may be needed to tackle the

integration challenges.

Proprietary Protocols

ATM systems are highly customised and use

proprietary protocols not used in IT systems.

Therefore, the threat detection engine in the SOC

should be updated with proprietary protocols used in

ATM systems to reduce false positives.

Standards

Aviation specialists in the UAE consider SOCs

necessary for monitoring ATM system security but

recommend establishing standards to guide

implementation (Awadhi, 2023). Standards can

establish uniformity and encourage OEMs to produce

systems easily onboarded and monitored by SIEMs.

Onboarding

Onboarding cyber assets to the SIEM involves three

fundamental processes. The first step is the discovery

and documentation of the critical systems.

Configuring the systems to generate appropriate logs

that the SIEM can ingest follows. Lastly, the system

must be configured to send the logs to the SIEM

(Onwubiko & Ouazzane). Configuring ATM systems

to generate logs that can be ingested and used to

detect threats by an SIEM should be prioritised when

planning and implementing a SOC. Work done in

other domains, such as using Software-Defined

Networks (SDN) to monitor 5G networks (Kecskés et

al., 2021), can be adopted in ATMs.

Radio Technology Systems

Most ATM systems are based on radio frequency

systems like VHF (Dave et al., 2022). Security threats

affecting these systems cannot be detected using the

methods used in IT systems. However, passive

artificial intelligence sensors can be deployed to

detect jamming, message injection and GPS spoofing

attacks (Tlili et al., 2024). A framework for ATM

systems should consider ways of detecting threats in

both IT and operation radio technology systems found

in ATMs.

Absence of Updates

ATM systems are designed to be in isolated networks

not connected to the Internet. As a result, ATM

systems do not get security updates. Security controls

such as antivirus systems installed on computing

systems for protection against malware and intrusion

are rendered useless. Whilst threats can be detected in

such systems, remediation measures are limited.

Emphasis on Safety

In aviation, safety refers to a condition where risks are

managed to an acceptable level. ICAO requires

aviation stakeholders to establish safety management

systems to reduce risks and prevent fatalities. Safety

measures require that new systems should be

tested comprehensively before implementation.

Cybersecurity systems such as SOCs should not cause

system failures that can affect safety. Therefore, it is

essential to consider how SOC aspects like auto-

remediation can jeopardise the safety of ATMs.

Domain-Specific Knowledge

ATM is a specialised field that requires domain-

specific knowledge. Experts in the field have

historically focused on safety before cyber security.A

survey by (Strohmeier et al., 2019) shows that

aviation experts generally understate the impact of

cybersecurity in their field. Cybersecurity experts, on

the other hand, believe that ATM systems have

vulnerabilities that malicious actors can easily exploit

(Dave et al., 2022)The two groups of experts are

critical to the success of SOCs in ATMs, and a

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

280

framework for the sector should address the

differences in opinions and ensure cooperation.

7 ATM SOC FRAMEWORK

Studies have shown that success with SOCs is

dependent on customisation (Vielberth et al.),

(Onwubiko & Ouazzane) and (Schinagl et

al.)Therefore, it is essential to incorporate the

requirements above into a SOC framework for ATM

systems. The proposed conceptual framework

is shown in Figure 3. It consists of major SOC

components, which are coloured orange, and essential

success factors, which are coloured blue.

When analysed, the requirements in section 6 can

be addressed by People, Processes, Governance and

Compliance, and Technology. Safety is the fifth

major component added to address ICAO safety

management systems requirements and encourage

buy-in from aviation specialists who downplay the

impact of cybersecurity in their domain (Strohmeier

et al., 2019) .

Figure 3: Proposed ATM SOC framework.

Technology components can address problems

with onboarding legacy systems and proprietary

protocols in ATM systems. In addition, technology

also caters to artificial intelligence methods that can

detect radio technology attacks such as jamming and

the absence of updates in closed ATM networks.

People address the knowledge gap between aviation

and cybersecurity specialists to ensure an effective

and efficient SOC. Standards are a perfect fit for the

processes component.

Top management's support for the SOC

strategically directs the rest of the organisation and

ensures funding availability. Financial resources are

also vital because implementing a SOC is expensive

to set up and run. The iterative continuous

improvement process addresses shortcomings

identified throughout the SOC's lifecycle. Thus,

incorporating these success factors into the

framework ensures that attention is formally placed

on them.

The five components and three success factors

proposed for the framework are essential for

establishing and managing a SOC in ATM.

8 CONCLUSION

ATM systems are inherently vulnerable to

cybersecurity threats as they were designed without

security considerations. Confidentiality, integrity,

and availability are not provided in most ATM

systems. Further challenges are introduced into the

ATM ecosystem by external systems that are

connected to ATMs. Threat actors can exploit

vulnerabilities that were not accessible when ATM

systems were isolated. However, if SOCs are

correctly implemented, they can be an effective tool

for monitoring, detecting, and responding to security

threats in ATM systems. Admittedly, one of the

critical factors for achieving success with a SOC is

customising it to suit the organisation's needs.

A conceptual framework is proposed to guide the

implementation of SOCs in the ATM domain and

address the absence of such a framework in

the literature. The conceptual framework

incorporates ATM-specific challenges and

requirements to enhance effectiveness and chances of

acceptance by aviation stakeholders. Future studies

will develop the framework further before seeking

validation from experts in the aviation industry.

REFERENCES

Agyepong, E., Cherdantseva, Y., Reinecke, P., & Burnap,

P. ( 2020). Towards a framework for measuring the

performance of a security operations center analyst.

International Conference on Cyber Security and

Protection of Digital Services (Cyber Security), Dublin,

Ireland.

Awadhi, Y. A. (2023). BHo Navigating the Digital Frontier:

The Crucial Role of SOC in Air Navigation Services

Barletta, V. S., Caivano, D., Vincentiis, M. D., Ragone, A.,

Scalera, M., & Martín, M. Á. S. (2023). V-SOC4AS: A

SOC

Continuous

improvement

Finance

Process

People

Top Management

Support

Technology

Governance and

Compliance

Safety

A Conceptual SOC Framework for Air Traffic Management Systems

281

Vehicle-SOC for Improving Automotive Security.

Algorithms, 16(2), 112.

Batuwangala, E., Kistan, T., Gardi, A., & Sabatini, R.

(2018). Certification challenges for next-generation

avionics and air traffic management systems. IEEE

Aerospace and Electronic Systems Magazine, 33(9),

44-53.

Danquah, P. (2020). Security Operations Center: A

Framework for Automated Triage, Containment and

Escalation. Journal of Information Security, 11(4), 225-

240.

Dave, G., Choudhary, G., Sihag, V., You, I., & Choo, K.-

K. R. (2022). Cyber security challenges in aviation

communication, navigation, and surveillance.

Computers & Security, 112, 102516.

Han, J., Ju, Z., Chen, X., Yang, M., Zhang, H., & Huai, R.

(2023). Secure operations of connected and

autonomous vehicles. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent

Vehicles.

ICAO. (2024). Global Air Navigation Plan Strategy.

Retrieved 29 April 2024 from https://www4.

icao.int/ganpportal/GanpDocument#/

Jacobs, P., Arnab, A., & Irwin, B. (2013). Classification of

security operation centers. Information Security for

South Africa, Sandton, South Africa.

Kandera, B., Holoda, Š., Jančík, M., & Melníková, L. (

2022). Supply chain risks assessment of selected

EUROCONTROL’s surveillance products. New

Trends in Aviation Development Novy Smokovec,

Slovakia.

Kecskés, M. V., Orsós, M., Kail, E., & Bánáti, A. (2021).

Monitoring 5g networks in security operation center.

2021 IEEE 21st International Symposium on

Computational Intelligence and Informatics,

Lekota, F., & Coetzee, M. (2021). Aviation Sector

Computer Security Incident Response Teams:

Guidelines and Best Practice. European Conference on

Cyber Warfare and Security, Online.

Lu, X., Dong, R., Wang, Q., & Zhang, L. (2023).

Information Security Architecture Design for Cyber-

Physical Integration System of Air Traffic Management

[Article]. Electronics (Switzerland), 12(7), Article

1665.

Majid, M. A., & Ariffin, K. A. Z. (2021). Model for

successful development and implementation of Cyber

Security Operations Centre (SOC). Plos one, 16(11), 1-

24.

Mughal, A. A. (2022). Building and Securing the Modern

Security Operations Center (SOC). International

Journal of Business Intelligence and Big Data

Analytics, 5(1), 1-15.

Mutemwa, M., Mtsweni, J., & Zimba, L. ( 2018).

Integrating a security operations centre with an

organization’s existing procedures, policies and

information technology systems. International

Conference on Intelligent and Innovative Computing

Applications Mon Tresor, Mauritius.

Nganga, A., Nganya, G., Lützhöft, M., Mallam, S., &

Scanlan, J. (2024). Bridging the Gap: Enhancing

Maritime Vessel Cyber Resilience through Security

Operation Centers. Sensors,

24(1).

Onwubiko, C., & Ouazzane, K. (2019). Cyber onboarding

is 'broken'. International Conference on Cyber Security

and Protection of Digital Services, Cyber Security

Oxford, UK.

Osechas, O., Mostafa, M., Graupl, T., & Meurer, M. (2017).

Addressing vulnerabilities of the CNS infrastructure to

targeted radio interference. IEEE Aerospace and

Electronic Systems Magazine, 32(11), 34-42.

Paganini, P. (2024). Israel army hacked the communication

network of the Beirut Airport control tower. Security

Affairs. https://securityaffairs.com/169080/cyber-

warfare-2/idf-hacked-beirut-airport-control-tower.html

Schinagl, S., Schoon, K., & Paans, R. (2015). A framework

for designing a security operations centre (SOC). 48th

Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences,

Kauai, HI, USA.

Strohmeier, M., Martinovic, I., & Lenders, V. (2020).

Securing the air–ground link in aviation. The Security

of Critical Infrastructures: Risk, Resilience and

Defense, 131-154.

Strohmeier, M., Niedbala, A. K., Schäfer, M., Lenders, V.,

& Martinovic, I. (2019). Surveying Aviation

Professionals on the Security of the Air Traffic Control

System. Security and Safety Interplay of Intelligent

Software Systems, Cham.

Strohmeier, M., Schäfer, M., Pinheiro, R., Lenders, V., &

Martinovic, I. (2017). On Perception and Reality in

Wireless Air Traffic Communication Security. IEEE

Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems,

18(6), 1338-1357.

Tlili, F., Ayed, S., & Fourati, L. C. (2024). Towards a

Responsive Security Operations Center for UAVs.

International Wireless Communications and Mobile

Computing,

Vielberth, M., Bohm, F., Fichtinger, I., & Pernul, G.

Security Operations Center: A Systematic Study and

Open Challenges. IEEE Access, 8.

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

282