An Automata-Based Method to Formalize Psychological Theories:

The Case Study of Lazarus and Folkman’s Stress Theory

Alain Finkel

a

, Gaspard Fougea

b

and St

´

ephane Le Roux

Universit

´

e Paris-Saclay, CNRS, ENS Paris-Saclay, LMF, 91190, Gif-sur-Yvette, France

fi

Keywords:

Automata-Based Method, Formalization of Psychological Theories, Stress Theory, Compact-Automata,

Refinement.

Abstract:

Formal models are important for theory-building, enhancing the precision of predictions and promoting col-

laboration. Researchers have argued that there is a lack of formal models in psychology. We present an

automata-based method to formalize psychological theories, i.e. to transform verbal theories into formal mod-

els. This approach leverages the tools of theoretical computer science for formal theory development, for

verification, comparison, collaboration, and modularity. We exemplify our method on Lazarus and Folkman’s

theory of stress, showcasing a step-by-step modeling of the theory.

1 INTRODUCTION

Context: For decades, some researchers have been

arguing that the field of psychology is in a state of cri-

sis. (Meehl, 1978) expressed that ”Theories in “soft”

areas of psychology lack the cumulative character of

scientific knowledge”. The study (Open Science Col-

laboration, 2015) showed that about half of the liter-

ature in psychology does not replicate. Several re-

searchers express that these crises stem partly from a

lack of formal models in psychology (Meehl, 1978;

Borsboom et al., 2021; Robinaugh et al., 2021).

Most psychological theories are verbal theories,

i.e. expressed in natural language, with all of its im-

precision (Haslbeck et al., 2022). This imprecision

makes it difficult to make precise predictions (Robin-

augh et al., 2021), which are necessary to validate or

falsify a theory. Furthermore, according to (Robin-

augh et al., 2021), ”verbal theories do not lend them-

selves to collaborative development”, explaining why

theories in psychology are like ”toothbrushes” (“no

self-respecting person wants to use anyone else’s”,

(Mischel, 2008)).

(Smaldino, 2019), (Muthukrishna and Henrich,

2019)) and (Robinaugh et al., 2021) argue that formal

models will address some of the theoretical issues of

psychology: ”We argue that formal theories provide

this much needed set of tools, equipping researchers

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2482-6141

b

https://orcid.org/0009-0004-8357-5340

with tools for thinking, evaluating explanation, en-

hancing measurement, informing theory development,

and promoting the collaborative construction of psy-

chological theories” (Robinaugh et al., 2021).

Expected Properties of a Formal Model for

Psychology: Following (Wing, 2006), we are in-

spired by the computational thinking that involves de-

composing complex theories, identifying patterns, fo-

cusing on essential details, designing step-by-step so-

lutions and evaluating their effectiveness. Let us pro-

pose a list of desirable properties that, we believe, for-

mal method for psychological theories should satisfy.

1. Openness to all psychological theories, both cog-

nitive and behavioral,

2. Modularity (easy to modify, compose, and refine),

3. Having a formal semantics,

4. Formal composition and refinement,

5. Capability to handle large systems,

6. Possibility of step-by-step simulation,

7. Formal verification of properties (psychological

model checking) with the use of automatic tools,

8. Formal (and automatic) comparison of models,

with automatic determination of compatibility be-

tween theories.

Properties Satisfied by Psychological Models:

We identify 13 well-known frameworks used in psy-

204

Finkel, A., Fougea, G. and Roux, S. L.

An Automata-Based Method to Formalize Psychological Theories: The Case Study of Lazarus and Folkman’s Stress Theory.

DOI: 10.5220/0013175400003896

In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Model-Based Software and Systems Engineering (MODELSWARD 2025), pages 204-215

ISBN: 978-989-758-729-0; ISSN: 2184-4348

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

chology which we will list below. For each of these

frameworks, we examine which of the eight above-

mentioned properties are satisfied.

Let us recall briefly these 13 models.

ACT-R (Adaptive Control of Thought - Rational) sim-

ulates human cognitive processes (Anderson, 2004)

with formal and non formal models. ACT-R satis-

fies modularity, step-by-step simulation, and open-

ness to theories but lacks formalization, verifica-

tion, and automatic comparison. Friston’s Predic-

tive Coding and Free Energy Principle postulates that

the brain minimizes prediction errors (Friston, 2009),

and it is used to explain perception and decision-

making. Friston’s Free Energy Principle excels in

formal aspects and adaptability to complex systems

but struggles with modularity and automatic verifica-

tion. GWT (Global Workspace Theory), initiated by

Baars, suggests consciousness arises when informa-

tion is shared across the brain (Baars, 1997, 2005).

LIDA (Learning Intelligent Distribution Agent) is

based on global workspace theory, simulating atten-

tion, memory, and decision-making (Stan Franklin,

2007). LIDA is modular and handles large systems

but lacks formal semantics and verification tools. The

Working Memory Model breaks memory into com-

ponents for processing (Baddeley and Hitch, 1974).

Global Workspace Theory is conceptual, suited for

theoretical exploration but lacks formalization and

automatic verification. Dual-Process Theory distin-

guishes between fast, automatic thinking (System 1)

and slow, deliberate thinking (System 2) (Kahneman,

2011). Dual-Process Theory is not formalized, re-

maining a conceptual framework. Bayesian networks

are widely used to model decision-making, proba-

bilistic reasoning, and learning (Pearl and Macken-

zie, 2018). Bayesian networks satisfy most crite-

ria, with formal semantics and modularity. Neural

networks simulate cognitive processes like memory,

learning, and pattern recognition, mimicking brain

function (Goodfellow et al., 2016). Neural networks

manage complex systems but lack formalization and

verification. Dynamic systems are used to model con-

tinuous behaviors over time, such as emotional dy-

namics, motivation, and behavioral regulation (Lake

et al., 2017). Game theory is applied in social psy-

chology to examine how persons make strategic de-

cisions in competitive or cooperative contexts (Sun,

2016). Propositional and modal logic are often used

to formalize human reasoning (Marr, 2015). Percep-

tion, attention, and memory are treated as information

processing systems, applying entropy and redundancy

to explain encoding, storage, and retrieval (Goodfel-

low et al., 2016). Markov decision processes (MDP)

model decision-making in uncertainty, while agent-

based models simulate complex social and ecological

interactions (Sun, 2016). The last 4 models listed pre-

viously (dynamic systems, game theory, propositional

and modal logic, and MDPs) largely meet the criteria,

offering powerful tools for formal modeling and sim-

ulation, though some lack psychological verification

or automatic comparability.

We conclude that no existing model, tool or

method totally satisfy all the 8 previous properties.

More specifically, most models satisfy neither formal

verification of properties (property 7) nor decidable

comparison between theories (property 8). Surpris-

ingly, almost none of these models use the automaton

model, which is the basis of computer science.

Formalization with Systems of Automata: Al-

though the notion of algorithms is used in many fields,

few researchers are familiar with the classical models

of computability. This is the case in neuroscience and

psychology. Yet, the conceptual foundations of com-

puter science would be quite useful for psychology,

which also deals with notions of states, actions, be-

haviors, simulation, and process equivalence, among

others. Even computational psychiatry (Montague

et al., 2012), which emerged in the 2010s, does not

use computability but rather game theory, probabilis-

tic models, statistics, and machine learning. Further-

more, finite automata diagrams are intuitive and un-

derstandable for researchers without a formal training

in mathematics or computer science.

Our Contributions:

• We present a new automata-based method to for-

malize psychological theories. In the spirit of

(Fodor, 1983), we build our model by defining and

composing modules. Our methodology is based

on the principle of modeling different modules

with different finite automata which will interact

in a very specific way. These modules can be

easily modified and refined without changing the

whole model.

• We provide a method that satisfies the eight prop-

erties listed previously.

• Our method is demonstrated using the example of

stress theory.

• We propose a list of new open questions.

Our (first) modeling, based on finite automata, is only

a first stage, and we will continue by adding time

(with timed automata), probabilities (with Markov

chains), and differential equations on continuous vari-

ables.

An Automata-Based Method to Formalize Psychological Theories: The Case Study of Lazarus and Folkman’s Stress Theory

205

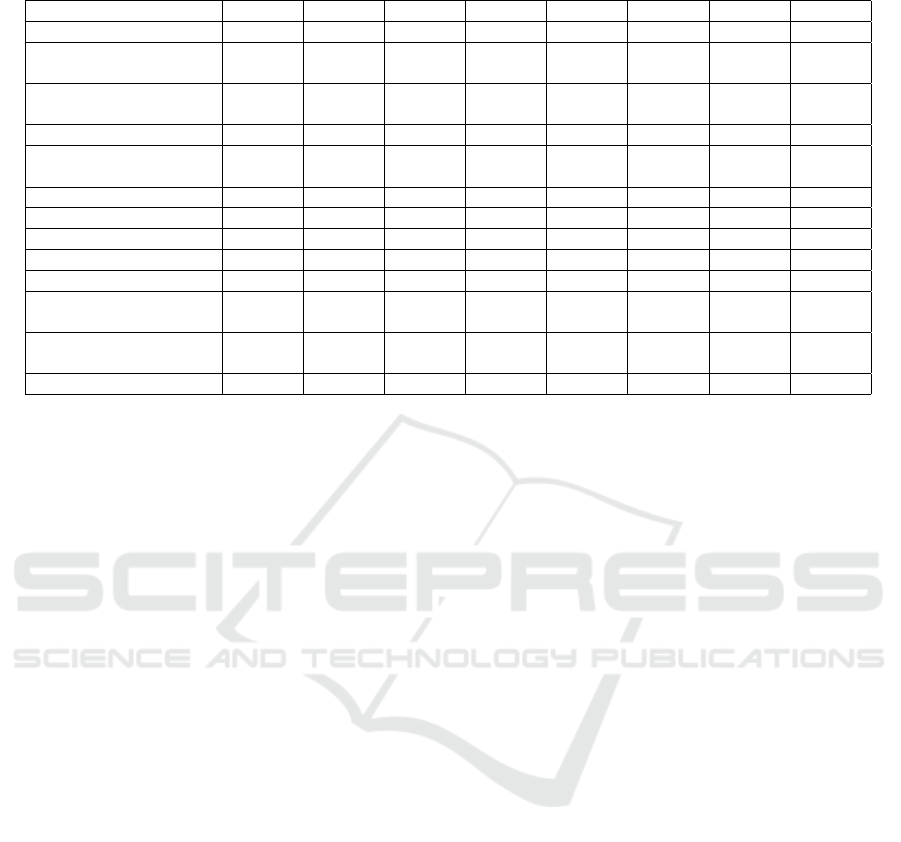

Table 1: Models and properties.

Model 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

ACT-R Yes Yes Partially Partially Partially Yes Partially Partially

Friston’s Free Energy

Principle

Yes Partially Yes Partially Yes Partially No No

GWT (Global

Workspace Theory)

Partially Partially No No Partially Partially No No

LIDA Yes Yes Partially Partially Yes Yes No No

Working Memory

Model

No Yes No No Partially No No No

Dual-Process Theory Partially No No No No No No No

Bayesian Networks Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Partially Yes

Neural Networks Yes Partially No Partially Yes No No No

Dynamic Systems Yes Partially Yes Partially Yes Yes Partially No

Game Theory Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Partially Yes

Propositional/Modal

Logic

Partially Yes Yes Yes Partially Yes Yes Yes

Information Processing

Models

Partially Yes Yes Yes Partially Yes Partially Yes

MDPs Yes Yes Yes Yes Partially Yes Partially Yes

Structure of the Paper: Section 2 introduces

compact-automata and refinements to formalize the

development of a theory into successive formal sys-

tems. Section 3 briefly presents the Lazarus and Folk-

man’s (verbal) theory of stress. Section 4 unfolds a

step by step refinement process to translate the verbal

theory into a formal model: we successively add cog-

nitive appraisal, stress, environment, coping, primary

and secondary appraisal and finally commitments.

2 COMPACT AUTOMATA AND

REFINEMENT

Throughout this paper, Σ will be a non-empty finite

set which we call the alphabet. Let us recall that a

finite automaton (without accepting states) on Σ is a

tuple (Σ,Q,δ,I), where Q is the finite set of states,

δ ⊆ Q × Σ × Q is the transition relation, and I ⊆ Q is

the finite set of initial states.

2.1 Synchronized Automata

There are various systems of (extended) finite au-

tomata that synchronise by communication: via

rendez-vous (Milner, 1989; Balasubramanian et al.,

2023), blocking or non-blocking (Guillou et al.,

2023), broadcast, FIFO queues, or shared memory

(Atiya et al., 1991; Moiseenko et al., 2021).

For the remainder of this article, let τ /∈ Σ and Σ

τ

=

Σ ∪ {τ} and [n] = {1, 2,...,n}. Let us now introduce a

generalized rendezvous.

Definition 1. A system of n automata synchro-

nized via generalized rendezvous (short: system)

is a n-tuple S = (A

1

,A

2

,...,A

n

) where every A

i

=

(Σ

τ

,Q

i

,∆

i

,I

i

) is a finite automaton.

The operational semantics of a system S =

(A

1

,A

2

,...,A

n

) is the finite automaton A(S) =

(Σ

τ

,Q,∆,I) defined as follows. The set of (global)

states is Q = Q

1

× ... × Q

n

. For all q ∈ Q, let us write

q

i

for the i

th

element of a (global) state q = (q

1

,...,q

n

).

The set of (global) initial states is I = I

1

×...×I

n

. The

(global) transition relation, ∆ ⊆ Q ×Σ

τ

×Q, is defined

by the two following rules:

1. τ-transitions: Let i ∈ [n], q,q

′

∈ Q such that

(q

i

,τ,q

′

i

) ∈ ∆

i

, then if for all j ∈ [n] − {i}, q

j

= q

′

j

,

there is a τ-transition q

τ

−→ q

′

, which stands for

(q,τ,q

′

) ∈ ∆.

2. Synchronised Transitions: Let q, q

′

∈ Q,a ∈

Σ. Let us note J

a

= {i ∈ [n] | ∃p

i

,r

i

∈ Q

i

s.t.

(p

i

,a,r

i

) ∈ ∆

i

} the set of indices of the automata

that contain at least one a-transition. If J

a

̸= ∅,

and for all i ∈ J

a

, (q

i

,a,q

′

i

) ∈ ∆

i

and for all i /∈ J

a

,

q

i

= q

′

i

, then there is a synchronised transition

q

a

−→ q

′

, which stands for (q,a,q

′

) ∈ ∆.

An a-transition (p,a,r) ∈ ∆ is enabled when all the

automata A

i

such that i ∈ J

a

(i.e., A

i

have at least a

local a-transition) are ready to enable an a-transition.

Every τ-transition (p, τ,r) is local and do not depend

on other automata for its execution. There is no block-

ing condition on τ-transitions.

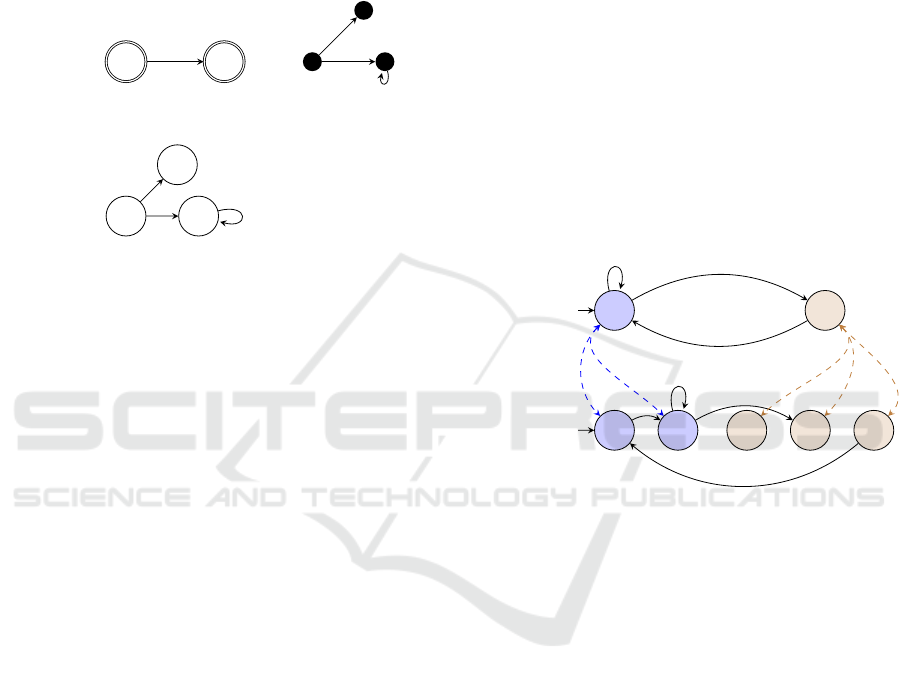

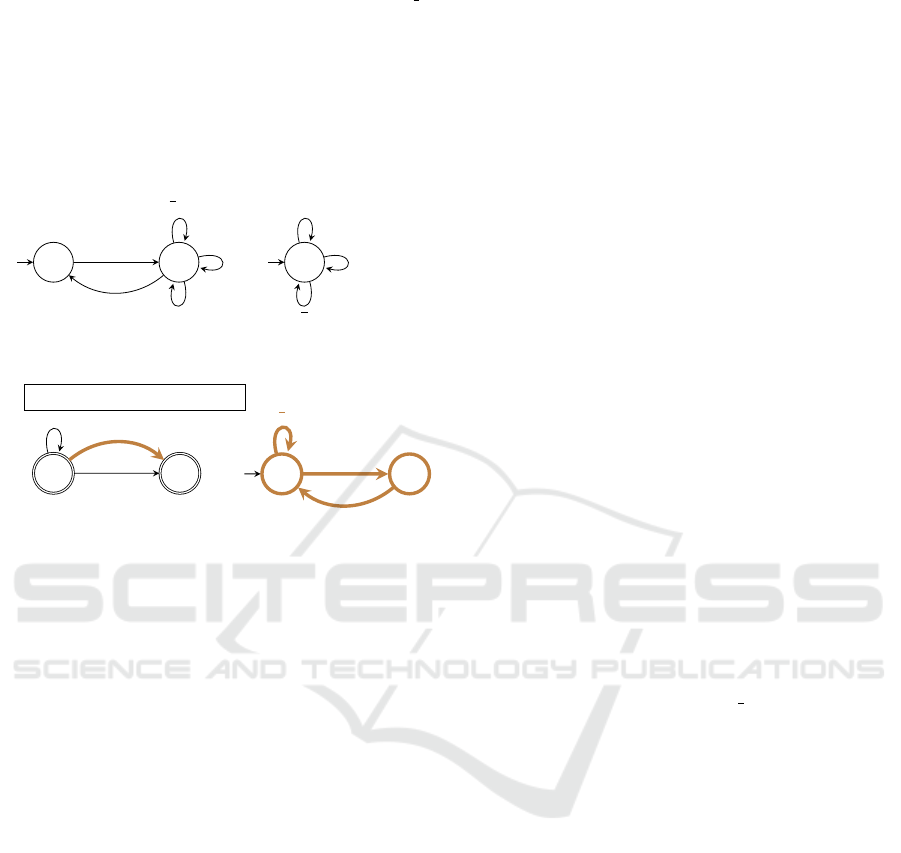

Example 1. Consider the system (A

1

,A

2

,A

3

) below:

We have J

a

= {1, 2}. Since 3 /∈ J

a

and there are

enabled (local) a-transitions in (local) states q

1

and

MODELSWARD 2025 - 13th International Conference on Model-Based Software and Systems Engineering

206

q

1

q

2

a

τ

τ

A

1

p

a

A

2

r

b

τ

A

3

Figure 1: Synchronised transitions and τ-transitions.

p, we have that (q

1

, p,r)

a

−→ (q

2

, p,r) is a transition in

∆ (we write (q

1

, p,r)

a

−→ (q

2

, p,r) ∈ ∆).

However, (q

2

, p,r)

a

−→ (q

2

, p,r) /∈ ∆, because 1 ∈

J

a

and there are no (local) a-transition is enabled in

(local) state q

2

.

Since there is no blocking-condition on τ-

transitions, we have that (q

2

, p,r)

τ

−→ (q

1

, p,r) ∈ ∆.

In writing (q

2

, p,r)

τ

−→ (q

2

, p,r) ∈ ∆, it is not pre-

cised whether the τ−transition is executed in A

1

or

in A

3

. This level of precision is enough for what we

model.

Here are two executions of our generalised ren-

dezvous system A(A

1

,A

2

,A

3

) :

(q

1

, p,r)

a

−→ (q

2

, p,r)

b

−→ (q

2

, p,r)

τ

−→ (q

2

, p,r)

τ

−→

(q

1

, p,r)

τ

−→ (q

1

, p,r)

(q

1

, p,r)

b

−→ (q

1

, p,r)

a

−→ (q

2

, p,r)

b

−→ (q

2

, p,r)

τ

−→

(q

2

, p,r)

2.2 Compact-Automata

Some of the automata that we will consider in Sec-

tion 4 contain a large number of states and transitions.

We will thus use compact-automata as a way of rep-

resenting these automata. Compact-automata do not

have a behaviour of their own, and they are useful

since they are compact versions of finite automata,

able to represent large and complex automata in a

compact and simple way. Below we define compact-

automata and the (deterministic) unfolding process.

Later we will explain the (non-deterministic) fold-

ing process. Let us fix notations. As previously,

Σ

τ

= Σ ∪ {τ} is an alphabet. Let also V = {v

1

,v

2

,v

3

}

be a set of three variables, and FO(V ,=,P

G

) denotes

the set of first order logic formula with relation =,

variables in V and with predicate P

G

meaning that

(v

1

,v

2

,v

3

) is an edge of G (for a graph G).

Definition 2. A compact-automaton is a tuple

˜

A =

(Σ

τ

,

˜

Q,X, f ,

˜

δ,I), where

˜

Q is the set of (compact)

states, X is the non-empty set, f :

˜

Q −→ P (X ) is the

unfolding function,

˜

δ ⊆

˜

Q × FO(V ,=,P

G

) ×

˜

Q is the

(compact) transition relation, and I ⊆ ∪

˜q∈

˜

Q

f ( ˜q).

The unfolding of such

˜

A is A = (Σ

τ

,Q,δ,I) with

Q = ∪

˜q∈

˜

Q

f ( ˜q) and where the transition relation δ of

A is defined by δ = δ

1

∪ δ

2

, where:

δ

1

=

[

( ˜q,φ, ˜p)∈

˜

δ, ˜q̸= ˜p,a∈Σ

τ

{(x,a,y) | x ∈ f ( ˜q),y ∈ f ( ˜p),φ(x,a,y)} (1)

δ

2

=

[

( ˜q,φ, ˜q)∈

˜

δ,a∈Σ

τ

{(x,a,x) | x ∈ f ( ˜q),φ(x,a,x)} (2)

In Definition 2, term (1) refers to (compact) tran-

sitions where the origin and target (compact) states

are different. In this case, the unfolding can gener-

ate (unfolded) transitions for all pairs of origin and

target (unfolded) states. Term (2) refers to (compact)

loops. In this latter case, the unfolding may only gen-

erate (unfolded) loops: (with previous notations) if

( ˜q,φ, ˜q) ∈

˜

δ,x,y ∈ f ( ˜q),a ∈ Σ

τ

s.t. x ̸= y ∧ φ(x, a, y),

then (x,a,y) is not added to δ from term (2).

˜q

˜p

(v

2

= a)

(v

2

= b)

compact-automaton

˜

A

1

I = {x

0

}, f ( ˜q) = f ( ˜p) = X

⇝

x

0

x

1

x

2

a a

a

a

a

a

(finite) automaton A

1

unfolding

of

˜

A

1

a,b

a,b

a,b

Figure 2: Unfolding of a compact-automaton.

Example 2. Figure 2 is the unfolding of the compact-

automaton

˜

A

1

for X = {x

0

,x

1

,x

2

}.

Graphical Representation of Compact-Automata.

Let

˜

A = (Σ

τ

,

˜

Q,X, f ,

˜

δ,I) be a compact-automaton.

We use three types of graphical notations in compact-

automata diagrams:

1. Sets and Singletons: Let ˜q ∈

˜

Q. If | f ( ˜q) |> 1, we

represent the (compact) state ˜q as a double circle

around ˜q. If f ( ˜q) = {q}, we represent the (com-

pact) state ˜q as a simple circle around ˜q (same rep-

resentation as for finite automata).

˜q

| f ( ˜q) |> 1

˜q

f ( ˜q) = {q}

Figure 3: Graphical representations of sets and singletons.

2. Transitions with a Letter or a Variable: when

an element of FO(V ,=,P

G

) is of the form (v

2

=

a) for a letter a ∈ Σ

τ

, we will simply label the tran-

sition as a. When an element of FO(V ,=,P

G

) is

of the form [v

1

] = v

2

, and the origin state is written

[ ˜q], we can simply label the transition with ˜q.

An Automata-Based Method to Formalize Psychological Theories: The Case Study of Lazarus and Folkman’s Stress Theory

207

3. Graph Transitions: if ( ˜q, φ, ˜p) ∈

˜

δ, and there is a

directed labeled graph G, with labels of G belong-

ing to L ⊆ Σ

τ

, with f ( ˜q) ̸= f ( ˜p), f ( ˜q) = f ( ˜p) = X ,

and the vertices of G are X. If φ(v

1

,v

2

,v

3

) =

((v

1

,v

2

,v

3

) is an edge of G), then we label the

(compact) transition G/L.

x

y

G/L

Representation for

φ(v

1

,v

2

,v

3

) = ((v

1

,v

2

,v

3

) is an edge of G)

compact-automaton

˜

A

2

+

x

0

x

0

⇝

x

1

x

1

x

2

x

2

a

b

b

x

0

x

1

x

2

Unfolding of

˜

A

2

for X = {x

0

,x

1

,x

2

},

G and L = {a, b}

a

b

b

G

Figure 4: Graphical representation of graph transitions.

Folding. The folding process is non-deterministic.

From a large finite automaton, first we identify sets of

states for which the structure of transitions is similar;

second, we create a small number of (compact) states

and (compact) transitions that represent all the states

and transitions of the initial automaton.

2.3 Refinements of Automata

The notion of refinement helps us understand how

successive systems relate to one another: a more re-

fined system is modeled more precisely with regards

to the theory. Refinement between systems is ex-

pressed as a binary relation. In order to define it, we

used two intermediary definitions which correspond

to refinements over labels and transitions, and over

automata.

Let us consider two systems S = (A

1

,A

2

,...,A

n

)

and S

′

= (A

′

1

,A

′

2

,...,A

′

m

) with their asso-

ciated automata A(S) = (Σ

τ

,Q,∆,I) and

A(S

′

) = (Σ

′

τ

,Q

′

,∆

′

,I

′

). As usual, we note

Σ

τ

= Σ ∪ {τ} and Σ

′

τ

= Σ

′

∪ {τ}.

Definition 3. Refinement of Labels and Transitions:

We define the following relation ≤

1

on Σ

τ

∪ Σ

′

τ

as the

smallest relation satisfying the following condition:

For all labels λ ∈ Σ

τ

∪ Σ

′

τ

, τ ≤

1

λ and λ ≤

1

λ.

We extend this relation to elements of ∆ ∪∆

′

in the

following way : for all q

1

,q

2

∈ Q, p

1

, p

2

,∈ Q

′

,λ ∈

Σ

τ

,λ

′

∈ Σ

′

τ

we have (q

1

,λ, p

1

) ≤

1

(q

2

,λ

′

, p

2

) if and

only if λ ≤

1

λ

′

.

Definition 4. Refinement of Automata: let us

consider i ∈ [n], j ∈ [m]. We say that A

i

=

(Σ

τ

,Q

i

,∆

i

,I

i

) ≤

2

A

′

j

= (Σ

′

τ

,Q

′

j

,∆

′

j

,I

′

j

) iff there exists a

partition (Q

q

)

q∈Q

i

of Q

′

j

for which the following con-

ditions hold:

• Σ

τ

⊆ Σ

′

τ

• Transition Refinement: for all t

′

= (p

′

,λ

′

,q

′

) ∈ ∆

′

j

,

for p,q ∈ Q

i

such that p

′

∈ Q

p

and q

′

∈ Q

q

, there

exists a transition t = (p,λ,q) such that t ≤

1

t

′

• Refinement of initial states: for all q

′

∈ I

′

j

, ∃q ∈

I

i

,q

′

∈ Q

q

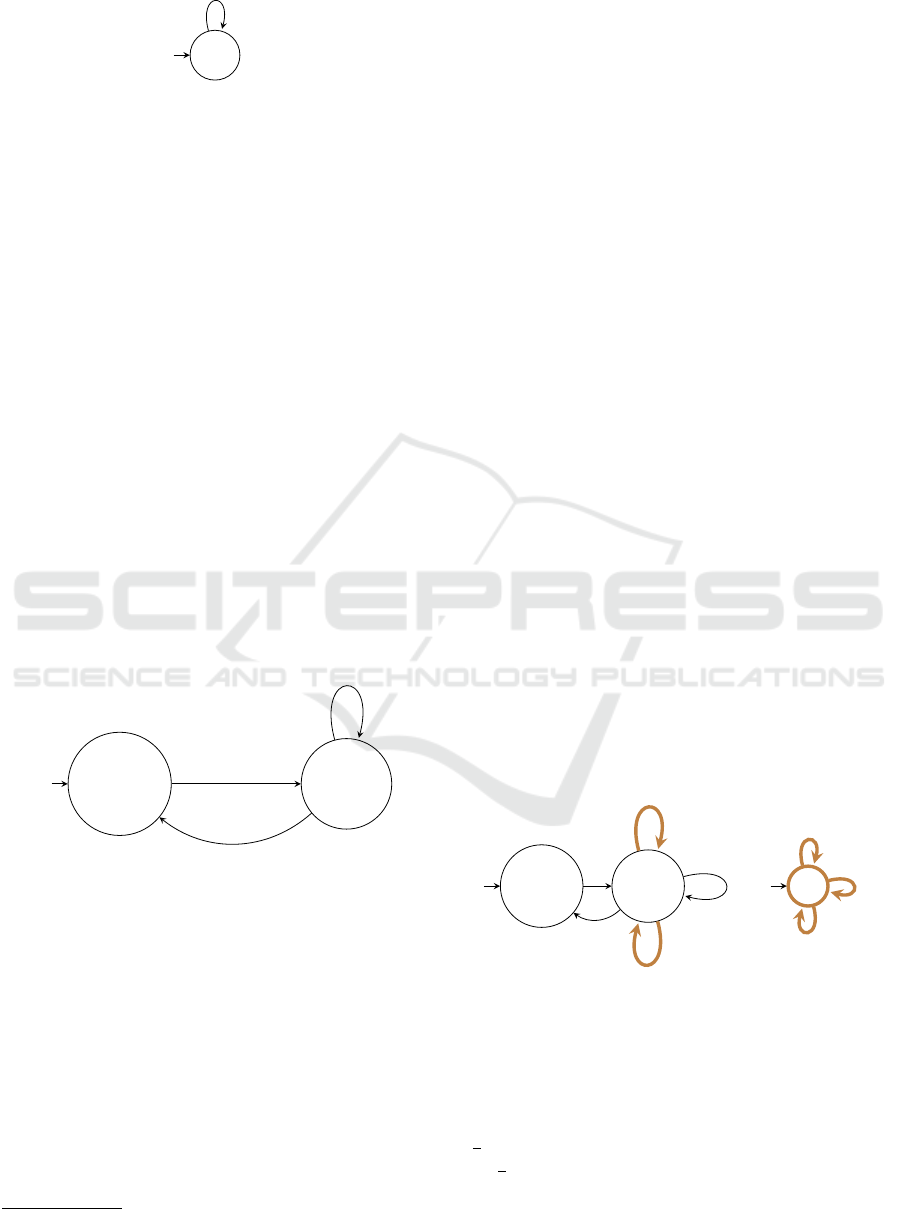

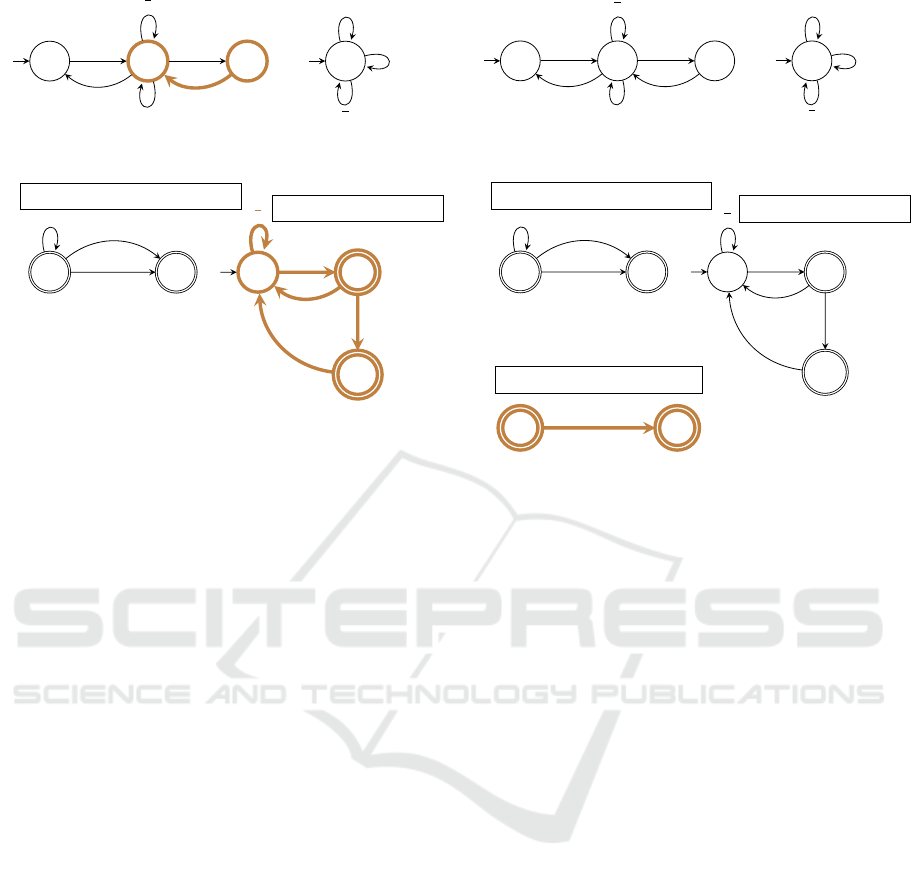

Example 3. Figure 5 explicits all possible ways of

refining transitions. Since there are no loops on q

2

there cannot be any transition between p

1

, p

2

, and

p

3

.

q

1

q

2

Automaton A

i

τ

a

τ

p

1

p

2

p

3

p

4

p

5

Automaton A

′

j

refinement of A

i

τ

b

a

c

Figure 5: Refinement of an automaton.

Let us recall that for all a ∈ Σ

τ

, J

a

= {i ∈ [n] |

∃p

i

,r

i

∈ Q

i

s.t. (p

i

,a,r

i

) ∈ ∆

i

} is the set of indices

of the automata that contain at least one a-transition.

For system S

′

and a ∈ Σ

′

we note it J

′

a

.

Definition 5. Refinement of Systems: For S =

(A

1

,A

2

,...,A

n

) and S

′

= (A

′

1

,A

′

2

,...,A

′

m

), we say that

S ≤

3

S

′

if and only if:

• n ≤ m

• For all 1 ≤ i ≤ n, A

i

≤

2

A

′

i

• For all a ∈ Σ, J

a

⊆ J

′

a

Remark 1. The three relations ≤

1

,≤

2

, and ≤

3

are

quasi-orders.

3 LAZARUS AND FOLKMAN’S

THEORY OF STRESS

This section explains the elements of Lazarus and

Folkman’s theory of stress that we have identified as

MODELSWARD 2025 - 13th International Conference on Model-Based Software and Systems Engineering

208

both important and suitable for modeling, see sec-

tion 4. These elements come from the book Stress,

appraisal and coping (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984),

and hence, every reference to pages in this section

points to pages of it. This book

1

is arguably one

of the most representative of this theory. We detail

these elements below, namely the relational definition

of stress, cognitive appraisal, primary appraisal, sec-

ondary appraisal, coping, emotional-focused coping,

problem-focused coping, and commitments.

Relational Meaning of Stress. Until the 1960s,

stress was defined either as a stimulus (stressor)

(p.12), or as a physiological response (stress re-

sponse) (p.14). These definitions fail to explain

the discrepancies in response between persons to

the same stimulus (p.19). This motivated Lazarus

and Folkman to introduce a relational definition of

stress, taking both aspects into account: ”Psychologi-

cal stress is a particular relationship between the per-

son and the environment that is appraised by the per-

son as taxing or exceeding his or her resources and

endangering his or her well-being” (p.19, l.26).

Cognitive Appraisal: is the process by which a per-

son determines whether a relationship is stressful or

not (p.19). This process is continuous during wak-

ing life (p.31) and contains two main processes: pri-

mary appraisal and secondary appraisal(p.31), which

”cannot be considered as separate” (p.43, l.8).

Primary Appraisal: is the process through which

a person answers the question of whether a particular

stimulus is beneficial, irrelevant or stressful (p.32).

Secondary Appraisal: is the process through

which a person evaluates the coping strategies avail-

able to deal with a stimulus appraised as stressful

(p.35).

Coping: is defined as ”constantly changing cogni-

tive and behavioral efforts to manage specific exter-

nal and/or internal demands that are appraised as tax-

ing or exceeding the resources of the person” (p.141,

l.10). Furthermore, it is said that the dynamic of

coping are ”a function of the continuous appraisals

(...) of the evolving person-environment relationship”

(p.142, l.32).

1

Which has gathered more than 95000 quotes according

to google scholar as of now

Emotion-Focused Coping and Problem-Focused

Coping. Coping strategies fall into two categories:

emotion-focused coping efforts are meant to regu-

late emotions, whereas problem-focused coping ef-

forts are meant to resolve the situation itself (p.150).

Commitments: ”express what is important to the

person, what has meaning for him or her.”(p.56, l.4)

They play a key role in the appraisal process, since

the stress experienced by a person is directly related

to how much meaning is tied to its commitments.

4 A MODEL FOR LAZARUS AND

FOLKMAN’S THEORY OF

STRESS

This section unfolds a step by step refinement process

to translate a verbal theory into a formal model. This

methodology consists in starting from a trivial initial

system, and at each step, either adding a new con-

cept from the theory, or refining a previously mod-

eled concept. At each step, new concepts or develop-

ments must be based on previously modeled concepts.

From this condition, next concepts or developments to

model are chosen with regards to their importance and

their simplicity. Every new system is a refinement of

the previous one. In this paper, the whole methodol-

ogy is not formally defined.

In the remainder of this paper, we will refer to

compact-automata as automata, referring to the un-

folding of a compact-automaton when it is mentioned.

Subsequent systems are noted S

1

,S

2

,S

3

,..., and for all

natural number i, and (compact or normal) automata

of system S

i

will be noted A

i.1

,A

i.2

,A

i.3

,...

All explanations from Section 3 were based on

the book Stress, appraisal and coping (Lazarus and

Folkman, 1984). Likewise, we will base our model-

ing solely on this book, and hence, every reference to

pages in this section points to pages of the book.

4.1 The Initial System

We begin with a (trivial) initial system S

1

= (A

1.1

),

which is meant to represent a system where nothing

yet has been specified. The universe is represented as

having an unique state, with some observed activity.

When we model a dynamic taking place which we do

not specify, we add a τ-transition. This is the role of

the τ-loop on state uni.

A

1.1

= (Σ

τ,1

,Q

1.1

,∆

1.1

,I

1.1

) with Σ

τ,1

= {τ},

Q

1.1

= {uni}, ∆

1.1

= {(uni,τ,uni)} and I

1.1

= {uni}.

An Automata-Based Method to Formalize Psychological Theories: The Case Study of Lazarus and Folkman’s Stress Theory

209

uni

τ

A

1.1

: initial automaton

Figure 6: System S

1

.

4.2 Adding Cognitive Appraisal

Here we model the key notion of cognitive appraisal

2

defined as follows: ”Cognitive appraisal can be most

readily understood as the process of categorizing an

encounter, and its various facets, with respect to its

significance for well-being(...) it is largely evaluative,

focused on meaning or significance, and takes place

continuously during waking life” (p.31, l.18)

Since what happens outside of waking life does

not seem to be explicited in the book, for the sake of

simplicity, we decide that appraisal happens only dur-

ing waking life. Since we know from the theory that

some activity takes place during appraisal, we add a

τ-loop on the ”appraisal” state. The fact that the loop

is labeled by τ means that we do not specify the na-

ture of this activity. Nothing is mentioned in the the-

ory about activity during the ”non-awake” state, and

hence we do not add a τ-loop on top of this state. This

leads to the following system S

2

= (A

2.1

) with one au-

tomaton with two states.

A

2.1

: Cognitive appraisal

non-awake

appraisal

τ

τ

τ

Figure 7: System S

2

.

Formally, the system S

2

consists only of au-

tomaton A

2.1

, where A

2.1

= (Σ

τ,2

,Q

2.1

,∆

2.1

,I

2.1

) is

defined by Σ

τ

= {τ}, Q

2.1

= {non-awake,awake},

∆

2.1

= {(non-awake,τ,appraisal),

(appraisal,τ,appraisal),(appraisal,τ, non-awake)},

and I

2.1

= {non-awake}.

System S

2

= (A

2.1

) is a refinement of system

S

1

= (A

1.1

): 1 ≤ 1, A

1.1

≤ A

2.1

, and since Σ

τ,1

=

{τ}, the third condition is always true. A

1.1

≤ A

2.1

because: if Q

uni

= {non − awake,appraisal}, then

(Q

uni

) is clearly a partition of Q

2.1

. For all transi-

2

blue-colored text points to other sections of the paper

tions (q,τ, p) of A

2.1

the transition (uni,τ,uni) satis-

fies τ ≤ τ and p,q ∈ Q

uni

. Finally, I

2.1

= {non-awake}

and non-awake ∈ Q

uni

.

4.3 Adding Stress

In Section 3 we discussed the relational definition of

stress. For now we will only distinguish between two

consequences of cognitive appraisal : ”no-stress”, and

”stress”.

To our previous system S

2

, we add a second au-

tomaton that calculates stress. The calculation of

stress can only happen during the appraisal state of

the first automaton. This way of modeling these sen-

tences is not unique, but will be coherent with the fur-

ther development of the theory.

Automata A

3.1

and A

3.2

synchronise on two let-

ters: ”stress” and ”no-stress”. The set of automata

that possess a (local) stress-transition is J

stress

=

{(3.1),(3.2)}. Hence, both automata must have an

enabled (local) stress-transition for a global stress-

transition to take place. This is why in (global) state

(non − awake, f ), a (global) stress-transition cannot

occur, whereas in (global) state (appraisal, f ), the

(global) stress-transition is enabled. Here is an ex-

ecution of the system:

(non − awake, f )

τ

−→ (appraisal, f )

stress

−−−→

(appraisal, f )

no−stress

−−−−−→ (appraisal, f )

τ

−→

(non − awake, f )

This execution described a person who wakes

up, appraises the person-environment relationship as

stressful, appraises again this relationship as non-

stressful, then goes back to sleep.

non-awake

appraisal

A

3.1

: Cognitive appraisal

τ

τ

stress

no − stress

τ

f

A

3.2

: Calculation of stress

stress

no − stress

τ

Figure 8: System S

3

.

In the remainder of this article, we will note na

for ”non-awake”, a for ”appraisal”, s for ”stress” and

s for ”no-stress”. Formally, S

3

= (A

3.1

,A

3.2

), Σ

τ

=

{s,s,τ}, and:

MODELSWARD 2025 - 13th International Conference on Model-Based Software and Systems Engineering

210

A

3.2

= (Σ

τ,3

,Q

3.2

,∆

3.2

,I

3.2

),Q

3.2

= { f }

∆

3.2

= {( f ,s, f ),( f ,s, f ), ( f , τ, f )}

I

3.2

= { f }.

A

3.1

= (Σ

τ,3.1

,Q

3.1

,∆

3.1

,I

3.1

),Q

3.1

= {na,a}

∆

3.1

= {(na,τ, a),(a,s,a),(a, s,a),(a,τ,na), (a,τ,a)}

I

3.1

= {r}.

System S

3

= (A

3.1

,A

3.2

) is a refinement of sys-

tem S

2

= (A

2.1

): 1 ≤ 2, A

2.1

≤ A

3.1

, and since Σ

τ,2

=

{τ}, the third condition is always true. A

2.1

≤ A

3.1

because if Q

non-awake

= {na} and Q

appraisal

= {a}

then (Q

non-awake

,Q

appraisal

) is a partition of Q

3.1

=

{na,a}. The two added transitions in ∆

3.2

from ∆

3.2

are (a,s, a) and (a, s,a), the other ones remaining ex-

actly the same. (appraisal,τ,appraisal) satisfies τ ≤ s,

τ ≤ s, and a ∈ Q

appraisal

. Finally, initial states are not

modified. In the remainder of this paper, we will not

detail the proof that each new system is a refinement

of the previous one.

4.4 Adding the Environment

We consider that the environment is a compact-

automaton A

4.3

= (Σ

τ

,

˜

Q

3

,X, f ,

˜

δ

3

,I

3

), on parameters

(X,G

τ

), where X is a finite set of states and G

τ

is a

directed labeled graph whose vertices are X and la-

bels are τ. Since this is the first compact-automaton

of our modeling, we detail it here. In the remain-

der of this paper, the details will only appear on

the graphical representations. We have

˜

Q = {x, y},

and f (x) = f (y) = X. We have that

˜

δ = {(x, (v

1

=

[v

2

]),y),(x,((v

1

,v

2

,v

3

) is an edge of G

τ

),y)}. The

second transition of

˜

δ is graphically labeled by

G

τ

/{τ}, see Subsection 2.2.

Appraisal happens ”continuously during waking

life”(p.31, l.23) (see Section 3). One way of mod-

eling the continuity of the appraisal process during

waking life is to have the ”Environment” automaton

”send” periodic updates of its state to the ”Cogni-

tive appraisal” automaton while it is in the ”appraisal”

state.

This is done via synchronised transitions: au-

tomata A

4.1

and A

4.3

synchronise over letters of X.

On automaton A

4.1

, the transition labeled by X means

that this transition exists for all x ∈ X . Let’s fix

x ∈ X. The name of the state associated with x in

the unfolded automaton of A

4.3

is [x], to avoid confu-

sion between states and transitions of the automaton.

Since J

x

= {(4.1),(4.3)}, the (global) x-transition

(a, f ,[x])

x

−→ (a, f ,[x]) is enabled. Automaton A

4.3

in

state [x] synchronises on letter x with A

4.1

when it is

in state a.

Here is an execution, when we have x

1

∈ X such

that (x

0

,τ,x

1

) is an edge of G

τ

:

(na, f ,[x

0

])

τ

−→ (a, f ,[x

0

])

x

0

−→ (a, f ,[x

0

])

s

−→

(a, f ,[x

0

])

τ

−→ (a, f , [x

1

])

x

1

−→ (a, f , [x

1

])

s

−→ (a, f , [x

1

])

This execution represents a person who wakes

up, perceives its environment, appraises the person-

environment relationship as stressful, the environ-

ment changes by itself, the person perceives it, and

appraises the new person-environment relationship as

non-stressful.

na a

A

4.1

: Cognitive appraisal

τ

τ

s,s

X

τ

f

A

4.2

: Calculation of stress

s

s

τ

[x]

[y]

A

4.3

: Environment

I

4.3

= {[x

0

]}, f ([x]) = f ([y]) = X

G

τ

/{τ}

x

Figure 9: System S

4

.

4.5 Adding Coping

We introduce a ”Coping”(see explanations in Section

3) automaton that models the decision of engaging in

coping efforts. Once a ”stress” appraisal has been cal-

culated in A

5.2

as a (global) s-transition, the ”Coping”

automaton gets to a state from which it can ”instruct”

the ”Environment” automaton to engage with coping

efforts, via new synchronised transitions.

As the environment, the modeling of coping has

parameters (C,G

C

), where C is a finite set of coping

strategies, and G

C

is a directed labeled graph whose

vertices are X and whose edges are labeled by ele-

ments of C. The ”Coping” automaton A

5.4

has two

states: ρ for ”rest” and [C] for the state where coping

efforts can be engaged. The ”Environment” automa-

ton was modified by adding transitions corresponding

to the edges of G

C

: for all x,z ∈ X,c ∈ C such that

(x,c,z) is an edge of G

C

, ([x],c,[z]) is a transition of

automaton A

5.3

. Each of these (local) transitions can

synchronise with automaton A

5.4

when it is in state

[C]. Although it is clear that humans can act when

they are not stressed, we only consider here coping

efforts which occur during psychological stress.

Let’s consider x

1

∈ X,c ∈ C such that (x

0

,c,x

1

) is

an edge of G

C

. Here is a possible execution of our

new system:

An Automata-Based Method to Formalize Psychological Theories: The Case Study of Lazarus and Folkman’s Stress Theory

211

(na, f ,[x

0

],ρ)

τ

−→ (a, f ,[x

0

],ρ)

x

0

−→ (a, f ,[x

0

],ρ)

s

−→

(a, f ,[x

0

],[C])

c

−→ (a, f , [x

1

],ρ)

x

1

−→ (a, f , [x

1

],ρ)

s

−→

(a, f ,[x

1

],ρ)

This execution represents a person who wakes

up, perceives its environment, appraises the person-

environment relationship as stressful, engages in cop-

ing efforts with coping strategy c, perceives the

changed person-environment relationship, appraises

it as non-stressful.

na a

A

5.1

: Cognitive appraisal

τ

τ

s,s

X

τ

[x]

[y]

A

5.3

: Environment

G

τ

/τ

G

C

/C

x

I

5.3

= {[x

0

]}, f ([x]) = f ([y]) = X

f

A

5.2

: Calculation of stress

s

s

τ

ρ

[C]

A

5.4

: Coping

s

C

s

Figure 10: System S

5

.

The notation C on a transition means that this tran-

sition exists for any letter c ∈ C.

4.6 Refining Appraisal into Primary

Appraisal and Secondary Appraisal

Primary and secondary appraisal are the two main

processes of cognitive appraisal.

To model these two processes, we refine the state

a of automaton A

5.1

into two states pa and sa. The

function of primary appraisal is the one conducted

by automaton A

5.2

, which remains unchanged as au-

tomaton A

6.2

which we rename ”Primary appraisal”.

Since secondary appraisal happens once a stimulus is

appraised as stressful, and that coping efforts are a

function of previous appraisals, it seems fitting to in-

clude secondary appraisal into the ”Coping” automa-

ton. The system loops between states pa and sa for a

while as a way of determining ”the degree of stress

and the quality (or content) of the emotional reac-

tion” (p.35, l.29).

Secondary appraisal happens after ”stress” has

been calculated by automaton A

6.2

((global) s-

transition) and before engaging in coping efforts. We

refine automaton A

5.4

by refining state [C] into 2|C|

states: [c] and [[c]] for all c ∈ C. We note C

′

= {[c],c ∈

C} and C

′′

= {[[c]],c ∈ C}. A (global) s-transition

leads non-deterministically to one state [c] ∈ C

′

which

will be evaluated. Two results are possible, coming as

two synchronised transitions between A

6.1

and A

6.4

:

”good” (letter g), or ”bad” (letter b). For a c ∈ C, a

”good” evaluation from state [c] brings A

6.1

back to

state pa, and A

6.4

to state [[c]] ∈ C

′′

, from which cop-

ing efforts are engaged for coping strategy c. A ”bad”

evaluation from state [c] will lead A

6.1

back to state pa

and A

6.4

back to state ρ. From this global state, an-

other primary appraisal can occur, and another strat-

egy can be evaluated. This is the loop between the

states pa and sa mentioned earlier.

Let us describe how the model S

6

=

(A

6.1

,A

6.2

,A

6.3

,A

6.4

) with c

1

,c

2

∈ C, x

1

∈ X

such that (x

0

,c

2

,x

1

) is an edge of G

C

, formalizes

the following human sequence: a person wakes up,

perceives its environment, appraises the person-

environment relationship as stressful, wonders if

coping strategy c

1

would be beneficial, perceives

c

1

as a bad strategy, wonders if coping strategy

c

2

would be beneficial, perceives c

2

to be a good

strategy, engages in coping efforts with strategy

c

2

, the environment changes, the person perceives

the new environment, the person appraises the new

person-environment relationship as non-stressful.

Here is the corresponding execution :

(na, f ,[x

0

],ρ)

τ

−→ (pa, f , [x

0

],ρ)

x

0

−→

(pa, f , [x

0

],ρ)

s

−→ (sa, f ,[x

0

],[c

1

])

b

−→ (pa, f ,[x

0

],ρ)

s

−→

(sa, f ,[x

0

],[c

2

])

g

−→ (sa, f ,[x

0

],[[c

2

]])

c

2

−→

(pa, f , [x

1

],ρ)

x

1

−→ (pa, f ,[x

1

],ρ)

s

−→ (pa, f ,[x

1

],ρ).

Remark 2. To our knowledge, the decision-making

mechanism between secondary appraisal and coping

is not detailed in (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). We

have chosen to model it in a very simple way: cop-

ing efforts are engaged when a coping strategy has

been evaluated as ”good”. Let’s note that any de-

cision making theory could be incorporated here in-

stead.

4.7 Adding Commitments

As seen in Section 3, commitments play an important

role in the appraisal process.

We model a commitment via a functions ϕ : X −→

{0,1}. The set of all such functions is noted Φ. At

this point, the set of internal variables is Φ and the

set of global states of the person-environment whole

is X ×Φ.

We interpret the functions ϕ as follows: in global

state (x,ϕ), the individual is stressed if and only if

ϕ(x) = 0.

MODELSWARD 2025 - 13th International Conference on Model-Based Software and Systems Engineering

212

na

pa

sa

A

6.1

: Cognitive appraisal

τ

τ

s

g,b

s

X

[x]

[z]

I

6.3

= {[x

0

]}, f ([x]) = f ([y]) = X

A

6.3

: Environment

G

τ

/{τ}

G

X

/C

x

f

A

6.2

: Calculation of stress

s

s

τ

ρ

[c]

[[c]]

s

b

c

([v

1

] = v

3

)

∧(v

2

= g)

s

f ([c]) = C

′

, f ([[c]]) = C

′′

A

6.4

: Secondary appraisal

and coping

Figure 11: System S

6

.

Since Φ is finite, we add a new ”Internal param-

eters” automaton A

6.5

. Transitions between states of

this automaton are coping efforts intending to affect

internal parameters (Emotion-focused forms of cop-

ing, see Section 3). The graph G

C

introduced in Sub-

section 4.5 is now renamed G

X

. The modeling of

coping affecting internal parameters has parameters

(Φ,G

Φ

), where G

Φ

is a directed labeled graph whose

vertices are Φ and whose edges are labeled by ele-

ments of C. For all c ∈ C, the (global) c-transition is

extended to automaton A

6.5

which then synchronises

with A

6.3

and A

6.4

.

Here is a simple example to show how this formal-

ism can be implemented.

Example 4. Here is a person’s description of his re-

lationship with money:

”It’s important for me to have enough money. I

want to feel like I’m safe financially. Enough money

for me is having more than 1000 euros in my bank

account. Right now I have enough money. Sometimes

people steal money from my bank account and I have

no money left. As a way to make myself feel better,

I try to save a lot of money each month, and I try to

think that money is not so important”

There are two states of the world

X = {≥ 1000,< 1000}, where ≥ 1000 (resp. <

1000) is the state where there is more (resp. strictly

less) than 1000 euros in the person’s bank account.

Let’s define ϕ : X −→ {0,1} such that ϕ(≥ 1000) =

1 and ϕ(< 1000) = 0 which corresponds to the com-

mitment expressed by the person.

Φ = {ϕ, 1 − ϕ, 1,0}, where 1 (resp. 0) is the func-

na

pa

sa

A

7.1

: Cognitive appraisal

τ

τ

s

g,b

s

X

[x]

[z]

I

7.3

= {[x

0

]}, f ([x]) = f ([y]) = X

A

7.3

: Environment

G

τ

/{τ}

G

X

/C

x

f

A

7.2

: Calculation of stress

s

s

τ

ρ

[c]

[[c]]

s

b

c

([v

1

] = v

3

)

∧(v

2

= g)

s

f ([c]) = C

′

, f ([[c]]) = C

′′

A

7.4

: Secondary appraisal

and coping

ϕ

ϕ

′

G

Φ

/C

I

7.5

= {ϕ

0

}, f (ϕ) = f (ϕ

′

) = Φ

A

7.5

: Internal parameters

Figure 12: System S

7

.

tion always equal to 1 (resp. to 0).

The only τ-transitions in the environmnent au-

tomaton A

6.3

correspond to ”Sometimes people steal

money from my bank account and I have no money

left”. Hence the two edges of G

τ

are (≥ 1000, τ,<

1000) and (< 1000,τ,< 1000).

C = {c

1

,c

2

}

The coping strategy c

1

corresponds to ”saving

money”. This strategy only affects the environment.

The coping strategy c

2

corresponds to ”trying to think

money is not so important”. This strategy only affects

internal parameters. Hence, the edges of G

X

are :

(< 1000,c

1

,< 1000),(< 1000,c

1

,≥ 1000),

(≥ 1000,c

1

,≥ 1000),(< 1000,c

2

,< 1000),

(≥ 1000,c

2

,≥ 1000).

The edges of G

Φ

are:

(ϕ,c

2

,ϕ),(ϕ,c

2

,1),(1,c

2

,1),(ϕ,c

1

,ϕ),(1,c

1

,1).

A transition (ϕ,c

2

,1) corresponds to a shift in the

person’s commitment with money.

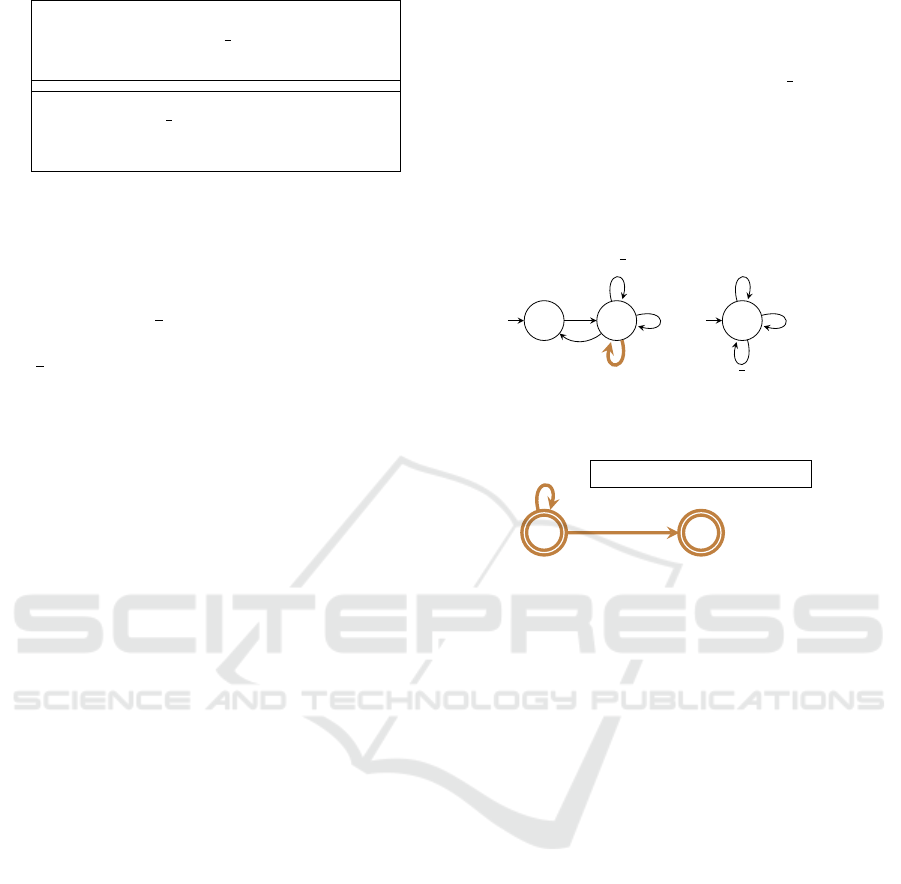

With this example, the diagrams of automata A

7.3

and A

7.5

are represented on Figure 13.

4.8 Further Developments

It is possible to refine the concept of primary appraisal

by calculating a result (”stress” or ”non-stress”) based

on the state of A

7.3

× A

7.5

.

The calculation of secondary appraisal can also be

modeled by adding an automaton which corresponds

to the inner representations of the person-environment

An Automata-Based Method to Formalize Psychological Theories: The Case Study of Lazarus and Folkman’s Stress Theory

213

[≥ 1000] [< 1000]

c

1

τ

≥ 1000

c

1

,c

2

c

1

,c

2

,τ

< 1000

A

7.3

: Environment

ϕ

1

1 − ϕ

0

c

1

,c

2

c

1

,c

2

c

2

A

7.5

: Internal parameters

Figure 13: Example of modeled environment and internal

parameters.

relationship, with an imagination process.

It is also possible to add other results of primary

appraisal, namely beneficial, irrelevant, harm/loss,

threat or challenge (p.32-33). For this, we can sim-

ply add other letters instead of s and s.

Several concepts or mechanism can be modelled

by adding internal parameters to automaton A

7.5

and

by changing the commitment functions to take the

new internal parameters into account. This can be

done for the interaction between primary and sec-

ondary appraisal (p.35), for beliefs about personal

control(p.65), as well as the concept of novelty (p.83).

5 CONCLUSION AND

PERSPECTIVES

Conclusion: We presented a new automata-based

method to formalize psychological theories, with an

example applied to stress theory. We demonstrated

how to create increasingly precise systems. Our

modelization allows for a large number of modules

that is not possible with a verbal theory.

Perspectives: We open the way to many directions of

research:

• Since we have represented psychological con-

cepts by both states and transitions, it is natural to

define the language of a theory T modelized by a

system S

n

either as the set of accepted words in Σ

∗

τ

(all states are final) of the system S

n

or as the set

of accepted sequences of transitions in ∆

∗

(where

∆ ⊆ Q × Σ

τ

× Q). We now have a canonical for-

mal object, i.e., a finite automaton, allowing us to

leverage the full range of conceptual and practical

tools from theoretical computer science. We are

now able to compare our theory with other theo-

ries also expressed by automata.

• Let S

i+1

be a system obtained by refinement of

system S

i

; prove (under realistic hypothesis) some

formal properties of refinement like L(S

i+1

) ⊆

L(S

i

) or S

i

simulates S

i+1

(for a simulation order-

ing to choose).

• We plan to apply our methodology and to build

formal models of many other theories like cogni-

tive theory of emotions, properties of short-term

memory, long-term memory, perception, repre-

sentations of the world, imagination, rational

thinking,...

• We will try to formalize into the computability

framework two theories of the mind and con-

sciousness like the Friston theory and the GWT.

• We will also extend our class of models by adding

probabilities, time and continuous variables.

• We will implement and automatically verify

some psychological theories with existing tools

like state-chart (Harel, 1987), event-b (Schnei-

der et al., 2014), NuSMV (Cimatti et al.,

2002) (A symbolic model checker), SPIN (Holz-

mann, 1997) (A tool for the formal verification

of distributed software systems) and UPPAAL

(Behrmann et al., 2004) (A tool for modeling,

simulation, and verification of real-time systems)

(Holzmann, 1997).

• We will host seminars and workshops to train re-

searchers in psychology to model theories with

this tool. This will be the opportunity to validate

the usefulness and usability of our tool.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the reviewers of the Modelsward confer-

ence for their insightful comments.

REFERENCES

Anderson, J. R. (2004). Cognitive Psychology and its Im-

plications. Worth Publishers.

Atiya, H., Koller, D., and Peleg, D. (1991). Shared memory

simulation of mutual exclusion automata. pages 169–

182. Distributed Computing, Springer.

Baars, B. J. (1997). In the Theater of Consciousness: The

Workspace of the Mind. Oxford University Press.

Baars, B. J. (2005). Global workspace theory of conscious-

ness: toward a cognitive neuroscience of human expe-

rience. pages 45–53. Progress in Brain Research.

Baddeley, A. and Hitch, G. (1974). Working memory. pages

47–89. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation.

Balasubramanian, A. R., Esparza, J., and Raskin, M.

(2023). Finding Cut-Offs in Leaderless Rendez-Vous

Protocols is Easy. Logical Methods in Computer Sci-

ence.

MODELSWARD 2025 - 13th International Conference on Model-Based Software and Systems Engineering

214

Behrmann, G., David, A., and Larsen, K. G. (2004). A tu-

torial on uppaal. In Formal Methods for the Design

of Real-Time Systems, International School on For-

mal Methods for the Design of Computer, Communi-

cation and Software Systems, SFM-RT 2004, Berti-

noro, Italy, September 13-18, 2004, Revised Lectures.

Springer.

Borsboom, D., Van Der Maas, H. L. J., Dalege, J., Kievit,

R. A., and Haig, B. D. (2021). Theory Construction

Methodology: A Practical Framework for Building

Theories in Psychology. pages 756–766. Perspectives

on Psychological Science.

Cimatti, A., Clarke, E., Giunchiglia, F., Roveri, M., Tac-

chella, A., and Tonetta, S. (2002). Nusmv 2: An open-

source tool for symbolic model checking. In Inter-

national Conference on Computer-Aided Verification,

pages 359–364. Springer.

Fodor, J. A. (1983). The Modularity of Mind: An Essay on

Faculty Psychology. MIT Press.

Friston, K. (2009). The free-energy principle: a rough guide

to the brain? pages 293–301. Trends in Cognitive

Sciences.

Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y., and Courville, A. (2016). Deep

Learning. MIT Press.

Guillou, L., Sangnier, A., and Sznajder, N. (2023).

Safety Analysis of Parameterised Networks with Non-

Blocking Rendez-Vous. arXiv.

Harel, D. (1987). Statecharts: a visual formalism for com-

plex systems. pages 231–274. Science of Computer

Programming.

Haslbeck, J. M. B., Ryan, O., Robinaugh, D. J., Wal-

dorp, L. J., and Borsboom, D. (2022). Modeling

psychopathology: From data models to formal theo-

ries. pages 930–957. Psychological Methods, Ameri-

can Psychological Association.

Holzmann, G. J. (1997). The model checker spin. In IEEE

Transactions on Software Engineering, pages 279–

295. IEEE.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar,

Straus and Giroux.

Lake, B. M., Ullman, T. D., Tenenbaum, J. B., and Gersh-

man, S. J. (2017). Building Machines that Learn and

Think Like People. Behavioral and Brain Sciences.

Lazarus, R. S. and Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal,

and coping. Springer, New York, 11. [print.] edition.

Marr, D. (2015). Vision: A computational investigation into

the human representation and processing of visual in-

formation. pages 3–23. MIT Press.

Meehl, P. E. (1978). Theoretical Risks and Tabular Aster-

isks:.

Milner, R. (1989). Communication & Concurrency. Pren-

tice Hall, New York, 1st edition edition.

Mischel, W. (2008). The Toothbrush Problem. APS Ob-

server.

Moiseenko, E., Podkopaev, A., and Koznov, D. (2021).

A survey of programming language memory models.

pages 439–456. Programming and Computer Soft-

ware, Pleiades Publishing.

Montague, P. R., Dolan, R. J., Friston, K. J., and Dayan,

P. (2012). Computational psychiatry. pages 72–80.

Trends in Cognitive Sciences.

Muthukrishna, M. and Henrich, J. (2019). A problem in

theory. pages 221–229. Nature Human Behaviour.

Open Science Collaboration (2015). Estimating the repro-

ducibility of psychological science. Science.

Pearl, J. and Mackenzie, D. (2018). The Book of Why: The

New Science of Cause and Effect. Basic Books.

Robinaugh, D. J., Haslbeck, J. M. B., Ryan, O., Fried, E. I.,

and Waldorp, L. J. (2021). Invisible hands and fine

calipers: A call to use formal theory as a toolkit for

theory construction. pages 725–743. Perspectives on

Psychological Science.

Schneider, S., Treharne, H., and Wehrheim, H. (2014). The

behavioural semantics of Event-B refinement. pages

251–280. Formal Aspects of Computing.

Smaldino, P. (2019). Better methods can’t make up for

mediocre theory. Nature.

Stan Franklin, S. J. D. (2007). A cognitive model of con-

sciousness and its role in cognition. In Proceed-

ings of the AAAI Fall Symposium on AI and Con-

sciousness: Theoretical Foundations and Current Ap-

proaches, pages 26–33.

Sun, R. (2016). Cognition and Multi-Agent Interaction:

From Cognitive Modeling to Social Simulation. Cam-

bridge University Press.

Wing, J. M. (2006). Computational thinking. pages 33–35.

Communications of the ACM.

An Automata-Based Method to Formalize Psychological Theories: The Case Study of Lazarus and Folkman’s Stress Theory

215