Using Machine Learning to Assess the Impact of Harsh Violent Discipline

on Children and Adolescents in Low- and Middle-Income Countries:

A Comparative Analysis Focusing on Its Relationship with Disabilities

Milena S. Barreira

1 a

, Ariane C. B. da Silva

1 b

, Hasheem Mannani

2

and Cristiane N. Nobre

1 c

1

Institute of Exact Sciences and Informatics, Pontifical Catholic University of Minas Gerais,

Dom Jos

´

e Gaspar, Belo Horizonte, Brazil

2

University College Dublin, Ireland

Keywords:

Violence, Disability, Adolescence, Children, Machine Learning, Severe Violence.

Abstract:

Children’s exposure to violence has long been a social and cultural concern, manifesting in various forms

across societies. According to UNICEF, approximately 300 million children worldwide, aged 2 to 4, expe-

rience regular violent discipline from caregivers, with around 250 million subjected to physical punishment.

This study leverages data from the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey to investigate the prevalence of severe vi-

olent discipline among children with and without disabilities in 54 low- and middle-income countries. Using

machine learning algorithms, including Decision Tree, Random Forest, XGBoost, Support Vector Machine

(SVM), and Neural Networks, the analysis revealed that SVM outperformed other models, achieving the high-

est precision, recall, and F1-score (with values of 78% and 80% for the violence and non-violence classes,

respectively). The results highlighted an increase in severe disciplinary violence correlated with the presence

of disabilities, particularly in contexts involving the domain of ‘controlling behavior’.

1 INTRODUCTION

Violent discipline, which includes physical, emo-

tional, or psychological punishment, is a concern-

ing issue that affects children and adolescents world-

wide. Epidemiological studies reveal that about three-

quarters of children aged 2 to 4 years old globally,

equivalent to 300 million children, are victims of psy-

chological aggression and/or physical punishment,

often perpetrated by their own caregivers

1

. These dis-

ciplinary methods include the application of physical

punishment, resulting in suffering and/or injury, as

well as degrading treatment that humiliates, seriously

threatens, or ridicules the child or adolescent.

Exposure to violence in childhood has been con-

sistently associated with detrimental effects on chil-

dren’s health, well-being, and future prospects (Sin-

horinho and de Moura, 2021). Unfortunately, chil-

dren with disabilities are at a higher risk of experienc-

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-3858-1284

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2477-4433

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8517-9852

1

Available at: https://data.unicef.org/resources/a-

familiar-face/

ing violent discipline compared to their non-disabled

peers (Emerson and Llewellyn, 2021). This vulnera-

bility is attributed to various factors, including social

stigmas, lack of support systems, and communication

barriers.

Moreover, children with disabilities are often

marginalized or underrepresented in public health

data, making it challenging to develop specific poli-

cies and interventions to address their unique needs.

Despite the growing recognition of the importance of

including people with disabilities, existing research

often overlooks the intersectionality between disabil-

ity and violence (UNICEF, 2021).

The Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS),

developed by the United Nations Children’s Fund

(UNICEF), is an essential tool for filling this data

gap. Through modules such as the Washington

Group/UNICEF Child Functioning Module (CFM),

MICS provides standardized and internationally com-

parable data on various aspects of child well-being,

including exposure to violence and disability status,

but without linking them. This data enables a compre-

hensive analysis of the intersection between disability

and severe violent discipline, informing policies and

interventions aimed at better protecting and support-

Barreira, M. S., B. da Silva, A. C., Mannani, H. and Nobre, C. N.

Using Machine Learning to Assess the Impact of Harsh Violent Discipline on Children and Adolescents in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Comparative Analysis Focusing on Its

Relationship with Disabilities.

DOI: 10.5220/0013184500003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 2: HEALTHINF, pages 161-172

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

161

ing children with disabilities, promoting their health,

well-being, and rights.

This study utilizes data collected by MICS to in-

vestigate the prevalence of exposure to harsh parental

discipline among children with and without disabili-

ties in various low- and middle-income countries. Ad-

ditionally, it seeks to understand how other factors,

such as gender, age, and country of birth, may influ-

ence these rates.

2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

2.1 Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys

The Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) is an

international household survey initiative developed by

UNICEF, aimed at filling data gaps and monitoring

human development

2

. MICS provides statistically ro-

bust and internationally comparable estimates of es-

sential indicators for tracking global goals and targets.

Initially designed to meet the goals of the 1990 World

Summit for Children, MICS has been conducted ev-

ery five years since 1995. In this study, we utilize data

from the sixth Multiple Indicator Survey (MICS6),

conducted between 2018 and 2019 by the Ministry of

Economy and Finance. The sixth round includes 72

questionnaires and 54 countries

3

, presenting 177 core

indicators and an average sample of 12,000 house-

holds, making it the largest round to date.

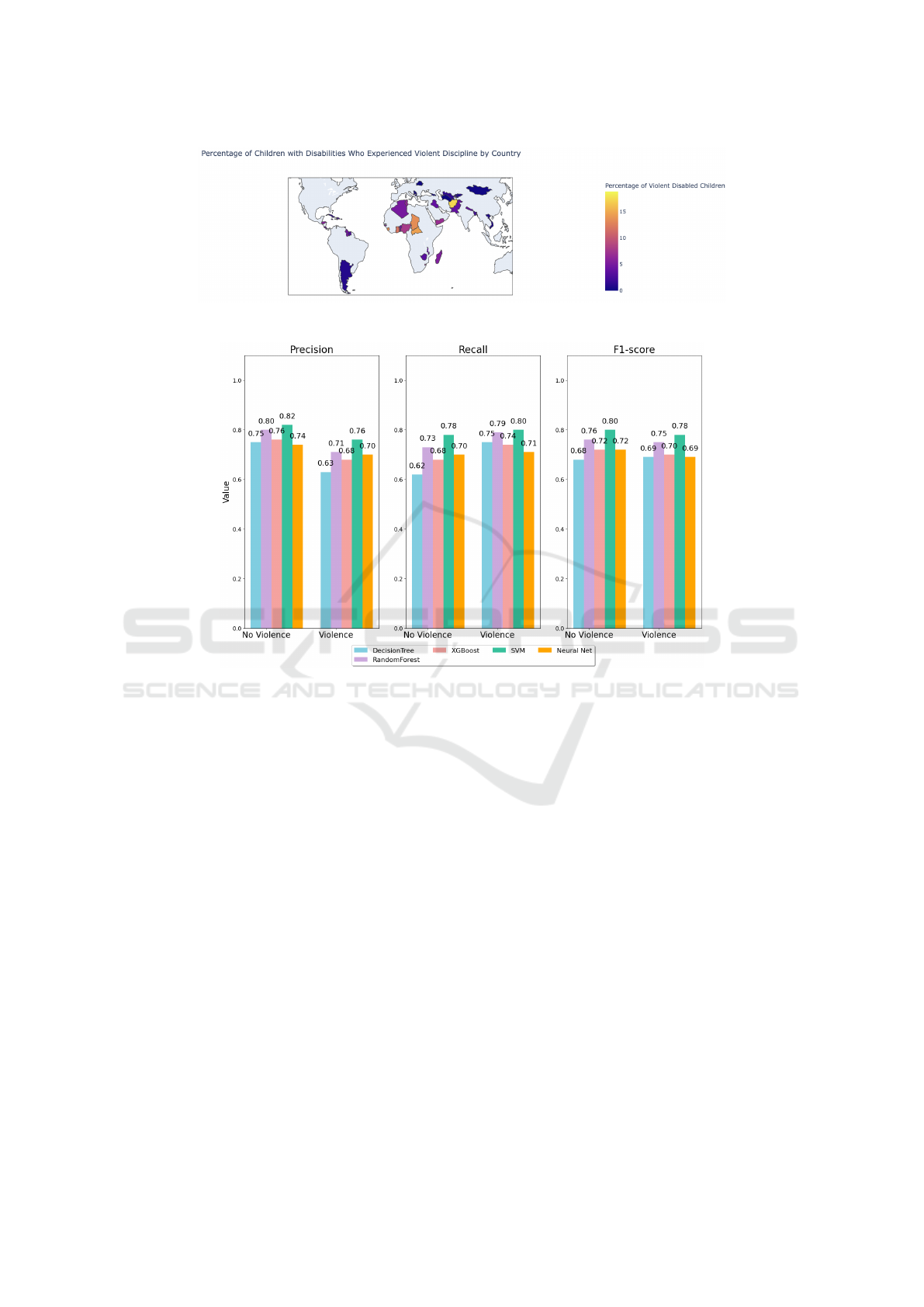

Figure 1: Countries analyzed in the sixth round of the

MICS.

Additionally, the MICS data are organized into

questionnaires that allow for various units of analy-

2

Available at https://mics.unicef.org

3

Afghanistan, Algeria, Argentina, Bangladesh, Belarus, Benin, Cen-

tral African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Democratic Republic of the Congo,

Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Eswatini, Fiji, Gambia, Georgia,

Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Guyana, Honduras, Iraq, Jamaica, Kiribati, Kosovo

under UN Security Council Resolution 1244, Kyrgyzstan, Lao People’s

Democratic Republic, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mongolia, Montene-

gro, Nepal, Nigeria, North Macedonia, Pakistan (divided into 4 provinces:

Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab, and Sindh), Samoa, S

˜

ao Tom

´

e

and Pr

´

ıncipe, Serbia, Sierra Leone, State of Palestine, Suriname, Thailand,

Togo, Tonga, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, Turkmenistan, Turks and Caicos

Islands, Tuvalu, Uzbekistan, Vietnam, Yemen, and Zimbabwe

sis. Depending on the focus of the research, up to ten

data files are generated and made available in SPSS

format, each corresponding to different units of anal-

ysis: hh.sav - Households; hl.sav - Household Mem-

bers; tn.sav - Mosquito Nets in Households; wm.sav

- Women (15 to 49 years); bh.sav - Birth History;

fg.sav - Female Genital Mutilation; mm.sav - Ma-

ternal Mortality; ch.sav - Children under five years;

fs.sav - Children aged 5 to 17 years; mn.sav - Men

(15 to 49 years).

In this study, we will focus on the file fs.sav, con-

centrating our analyses on children aged five to sev-

enteen years and their relationship with disciplinary

violence (FCD module) and disabilities (FCF mod-

ule).

2.2 Disabilities

Historically, the meaning of disability has been un-

derstood in various ways. The concept was initially

framed within religious discourses of Western Judeo-

Christian beliefs, where it was seen as a punishment

from God for specific sins committed by the person

with a disability (Jean A Pardeck, 2012). This re-

ligious perspective has gradually been replaced by

medical and scientific approaches, resulting in the

substitution of religious leaders by doctors and scien-

tists as cognitive authorities in social values and heal-

ing procedures.

In the narrative of the medical model, disability is

understood as an individual condition or medical phe-

nomenon that results in limited functioning deemed

deficient (Cecilie Bingham, 2013). This can occur

due to impairments of body functions and structures,

including the mind, caused by diseases, injuries, or

health problems. However, the medical model often

fails by focusing exclusively on the limitations associ-

ated with the person’s disability, without considering

the environments that may exacerbate or adversely af-

fect their functional abilities.

The medical model is often contrasted with the

social model of disability, which emphasizes the so-

cial and environmental factors that contribute to a per-

son’s disability. The International Classification of

Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) provides

a comprehensive approach to understanding disabil-

ity in children (Talo and Ryt

¨

okoski, 2016). It adopts

a biopsychosocial model that conceptualizes disabil-

ity as a complex interaction between biological, psy-

chological, and social factors, influencing the child’s

physical, mental, and social development. This defi-

nition encompasses a range of conditions, from phys-

ical impairments, such as vision loss, to limitations

in daily tasks and social restrictions, considering the

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

162

child’s participation in their environment. The ICF

classifies areas of disability into two main categories:

physical structures (organs, limbs, and the nervous,

visual, auditory, and musculoskeletal systems) and

bodily functions (hearing, memory, among others)

(Farias and Buchalla, 2005).

In this context of identifying children with disabil-

ities, the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS),

in its sixth round, employs modules developed by the

Washington Group on Disability Statistics (WGDS),

which categorize children’s difficulties into 13 do-

mains for children aged 5 to 17 years. These ar-

eas include difficulties in: seeing, hearing, mobil-

ity, self-care, communication/comprehension, learn-

ing, remembering, attention and concentrating, rela-

tionships, coping with change, affect ( anxiety and

depression ) and controlling behaviour

4

.

2.3 Violent Discipline

Violence is a complex phenomenon that continues

to pose a significant challenge in the field of health

(Linda L. Dahlberg, Etienne G. Kru, 2006). In this

context, according to Sinhorinho and Moura (2022),

children emerge as a particularly vulnerable group,

especially concerning family violence, which often

manifests as aggressive conflict resolution in inter-

personal relationships. The consequences of these

acts vary in magnitude and frequency

5

, but are pro-

foundly influenced by the child’s emotional, cogni-

tive, and physical development stage, affecting their

self-esteem and increasing the likelihood of behav-

ioral disturbances as well as anxiety and depression.

In this scenario, it is important to analyze the in-

fluence of violent discipline on children’s health and

development. UNICEF, for example, employed in

the sixth round of the Multiple Indicator Cluster Sur-

veys (MICS) studies that considered children aged

2 to 17 years and investigated whether they experi-

enced violent discipline in the past few months, with

responses categorized into non-violent discipline, se-

vere physical punishment, any type of physical pun-

ishment, any psychological aggression, and any vio-

lent discipline. UNICEF defines severe violent disci-

pline with criteria that include ‘Beat (him/her) up, that

is hit (him/her) over and over as hard as one could’,

‘Hit (him/her) on the bottom or elsewhere on the body

with something like a belt, hairbrush, stick or other

hard object’ and ‘Hit or slapped (him/her) on the face,

head or ears’.

4

Available at https://www.washingtongroup-disability.

com

5

Available at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-

sheets/detail/corporal-punishment-and-health

The caregivers were asked about the occurrence

of these behaviors in relation to the children, allow-

ing for yes or no responses for each form of violent

discipline, thus enabling a clear assessment of the in-

cidence of these behaviors.

3 RELATED WORKS

Emerson and Llewellyn (2021) investigated the im-

plications of exposure to violent discipline in chil-

dren with and without disabilities in 17 countries

6

of

low and middle income. Using data from the MICS,

the researchers analyzed whether children with dis-

abilities were statistically more likely to experience

eight distinct forms of violent discipline compared to

children without disabilities. The results indicated

a 71% higher probability of children with disabili-

ties being exposed to violent disciplinary measures in

these countries.

The study by Bhatia et al. (2023) analyzed MICS

data in 24 countries

7

, investigating the relationship

between disability and the higher incidence of lack of

birth registration, child labor, and violent discipline.

The study considered factors such as sex and country

of origin, in addition to exploring the interaction with

disability status. The authors highlight the scarcity of

research linking disability and violent discipline, em-

phasizing that the intersection with gender and coun-

try of origin remains underexplored.

The results revealed that girls with disabilities

have a higher likelihood of experiencing violent dis-

cipline compared to those without disabilities (27.1%

vs. 17.4%). Additionally, the prevalence of violent

discipline was 50% higher in 23 of the 24 countries

for children with disabilities, regardless of gender.

In the work by (Cuartas et al., 2018), the authors

also address exposure to both violent and non-violent

discipline in low- and middle-income countries

8

dur-

6

Montenegro, Suriname, Iraq, Georgia, Mongolia, Tunisia, Kiribati,

Ghana, Zimbabwe, Bangladesh, Lesotho, Kyrgyzstan, Gambia, Togo, Mada-

gascar, Congo, and Sierra Leone

7

Mongolia, Tonga, Kosovo, Kyrgyzstan, North Macedonia, Serbia,

Guyana, Suriname, Algeria, Iraq, Palestine, Bangladesh, Central African

Republic, Chad, Congo, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Lesotho, Madagascar, S

˜

ao

Tom

´

e and Pr

´

ıncipe, Gambia, Togo, and Zimbabwe

8

Afghanistan, Algeria, Argentina, Bangladesh, Belarus, Belize, Benin,

Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad,

Congo, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Ghana, Guinea-

Bissau, Guyana, Iraq, Jamaica, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Lao People’s

Democratic Republic, Lebanon, Macedonia, Malawi, Mexico, Moldova,

Mongolia, Montenegro, Nepal, Nigeria, Palestine, Panama, Paraguay, S

˜

ao

Tom

´

e and Pr

´

ıncipe, Serbia, Sierra Leone, Saint Lucia, Sudan, Suriname,

Eswatini, Togo, Tunisia, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, Uruguay, Vietnam, and

Zimbabwe.

Using Machine Learning to Assess the Impact of Harsh Violent Discipline on Children and Adolescents in Low- and Middle-Income

Countries: A Comparative Analysis Focusing on Its Relationship with Disabilities

163

ing early childhood. To this end, the study utilizes

MICS data collected between 2010 and 2016, aim-

ing to estimate the proportion of children aged 2 to 4

years who are exposed to violent discipline in their

homes. This study builds upon previous research,

such as the work by (Cappa and Khan, 2011), which

analyzes data from children aged 2 to 14 years in 34

countries of the MICS, concluding that, overall, par-

ents and caregivers resort to physical punishment and

aggression even in households where these practices

are not deemed necessary. In Yemen, 78% of chil-

dren subjected to physical punishment have parents

or caregivers who do not see these acts as necessary.

In addition, the study by Cuartas and collabora-

tors also relies on the research by Lansford in 2010

(Lansford et al., 2010), which observed that 54% of

female children and 58% of male children aged 7 to

10 years in nine different countries

9

had already ex-

perienced physical aggression at home, with 13% of

cases among females and 14% among males classified

as severe physical punishment.

The study (Fang et al., 2022) also provides rele-

vant data on the intersection between disability and

violence in children aged 0 to 17 years globally. The

research analyzed 18 international databases in En-

glish, covering physical, mental, intellectual, and sen-

sory disabilities, as well as chronic illnesses, to in-

vestigate the relationship between different forms of

violence and specific types of disability. The results

showed that children with disabilities are 2.08 times

more likely to be victims of violence compared to

those without disabilities. Moreover, children with

cognitive or mental health disabilities face higher lev-

els of violence, with emotional violence being the

most frequently reported and neglect presenting the

highest statistical probability.

The article by Hendricks et al. (2013) is essential

for understanding the relationship between childhood

disability and violent discipline. The research ana-

lyzes children aged 2 to 9 years and their caregivers in

17 low-income countries

10

, aiming to establish con-

nections between cognitive, sensory, and motor dis-

abilities and disciplinary violence, as well as investi-

gating the increased risk of punitive treatment and its

variation according to socioeconomic context.

The results revealed significant variations in vio-

lence, depending on the type of disability, age, and

country. Children with conduct and attention prob-

lems were more likely to experience violent disci-

9

China, Colombia, Italy, Jordan, Kenya, Philippines, Sweden, Thai-

land, and the United States

10

Albania, Belize, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cameroon, Central African

Republic, Djibouti, Georgia, Ghana, Iraq, Jamaica, Laos, North Macedonia,

Montenegro, Serbia, Sierra Leone, Suriname, and Yemen

pline. The study also explores how characteristics that

complicate the management of children may lead par-

ents to adopt stricter disciplinary methods. For exam-

ple, children with disabilities that affect verbal com-

munication, such as deafness, may be more suscepti-

ble to physical discipline due to communication diffi-

culties, which increase parents’ stress and frustration.

In (Pace et al., 2019), the authors analyze data

from 62 countries from the 4th and 5th rounds of the

MICS, aiming to investigate the relationship between

the practice of spanking a child and their behavior.

Various indicators were included, such as the child’s

age (3 to 4 years), their gender, the caregiver’s gen-

der, the belief that a child needs to be punished to be

raised correctly, the mother’s level of education, the

number of family members, the country of origin, and

whether they reside in an urban or rural area.

This study indicated that 43% of children were

spanked in the past few months or lived with another

child who was spanked during the same period. Fur-

thermore, 33% of caregivers reported believing in the

importance of corporal punishment for raising their

children. Additionally, it was observed that countries

with higher socio-emotional development tended to

practice corporal punishment less frequently on their

children.

Finally, it is noted that although there is a consid-

erable number of studies addressing the relationship

between children with disabilities and disciplinary vi-

olence, there is little information available on how

these factors relate to other variables, such as gen-

der, age, and economic situations of the country of

origin. Furthermore, many studies use outdated data,

failing to incorporate the sixth round of the MICS

from 2019, or they primarily focus on high-income

countries, thus not using MICS data as a basis. When

they do utilize MICS data, they do not always asso-

ciate these factors with disability, limiting their anal-

ysis to some low- and middle-income countries, and

they do not always represent the full diversity of chil-

dren with disabilities or predominantly consider se-

vere violent discipline. It is also important to note

that some studies analyze only a restricted age range,

such as children aged 2 to 9 years, even though MICS

provides comprehensive data. Thus, this article seeks

to fill these gaps in the literature by offering a more

complete and updated analysis of the topic.

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

164

Table 1: Comparison of Related Works.

Authors Used MICS-Data? MICS Round Age Range Disability Analysis? Violence Analysis? Number of Countries

Lansford et al. (2010) - 7-10 ✓ 9

Cappa and Khan (2011) ✓ 3 2-14 ✓ 34

Hendricks et al. (2013) ✓ 5 2-4 ✓ ✓ 17

Cuartas et al. (2018) ✓ 5 2-4 ✓ 49

Pace et al. (2019) ✓ 5 3-4 ✓ 62

Emerson and Llewellyn (2021) ✓ 6 2-14 ✓ ✓ 17

Fang et al. (2022) ✓ 3 2-9 ✓ ✓ 33

Bhatia et al. (2023) ✓ 6 2-17 ✓ ✓ 24

This Work ✓ 6 5-17 ✓ ✓ 54

4 MATERIALS AND METHODS

4.1 Description of the Database

The data used in this study were extracted from the

UNICEF website, specifically from the MICS (Multi-

ple Indicator Cluster Surveys) program.

For this analysis, data from the sixth round of

MICS (MICS6), initiated in 2018, were employed.

The data were collected through various standard-

ized questionnaires, which countries can customize

according to their needs. The questionnaires cover the

following categories: household information (includ-

ing a form for water quality testing), data on women

aged 15 to 49 years, information on men aged 15 to

49 years, data on children under five years old, infor-

mation on children aged 5 to 17 years, a vaccination

registration form in health facilities, and a question-

naire for water quality testing.

The main focus of this study was the data from

the questionnaire for children aged 5 to 17 years, ex-

tracted from the fs.sav file, with analysis centered

on the Child Discipline Module and the Child Func-

tioning Module. Although the study included data

from 62 countries, only 54 had complete and avail-

able data, as in some cases the data were empty or

duplicated.

4.2 Methodology

For preprocessing, the datasets from the 6th round of

the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS), cov-

ering 54 countries and children aged 5 to 17 years,

were downloaded and converted from .sav to .csv us-

ing the mics

library in Python.

Next, records with null values, such as ‘don’t

know’ or ‘no response’, as well as inconsistent or du-

plicated samples, were excluded. Categorical data

were processed: non-hierarchical categories, such

as continents, were encoded using one-hot encod-

ing, while ordered data, such as caregiver age, were

grouped into 5-year intervals and encoded with label

encoding.

In addition, new attributes were added, such as

population, area, birth rate, GDP per capita, female

and male life expectancy, and mortality rate, obtained

from the UNdata website

11

.

Attributes with many categories and few re-

sponses for each option, such as types of water supply,

were grouped for simplification and encoded. Nu-

meric variables were normalized to a range of 0 to

1.

Attributes related to the education level of the

caregiver, the child’s caregiver, and the child were re-

organized, unifying the categories ‘Lower Secondary

Education’ and ‘Upper Secondary Education’ into a

single column called ‘Secondary Education’.

Attributes that, after preprocessing, presented

only a single response option were discarded.

Outliers were identified and removed using the

Isolation Forest method, which isolates anomalous

samples by calculating the number of splits required

in the isolation trees.

Finally, records of children aged 15 to 17 were re-

moved, as the violent discipline module of the MICS

only includes data for children aged 5 to 14, resulting

in empty columns for these age groups.

After these preprocessing steps, two main in-

stances were selected for analysis in this study:

‘FCD2’ and ‘FCF’. The instance ‘FCD2’ represents

the module in the MICS that deals with violent dis-

cipline, while the instance ‘FCF’ addresses disabil-

ity. The variables ‘FCD2G’, ‘FCD2I’, and ‘FCD2K’,

which correspond to the methods of violent discipline

discussed in Section 2.3, were analyzed. Only these

variables were examined, as they are considered by

the MICS to be the most severe forms of violence

11

UNdata is an online service from the UN that pro-

vides access to a vast collection of international statistical

databases, allowing users to search and download informa-

tion on topics such as health, education, economy, and en-

vironment.

Using Machine Learning to Assess the Impact of Harsh Violent Discipline on Children and Adolescents in Low- and Middle-Income

Countries: A Comparative Analysis Focusing on Its Relationship with Disabilities

165

present. The data were normalized to ensure consis-

tency in the responses, and all were converted to En-

glish. If at least one of the two variables from the vio-

lent discipline module contained the response ‘YES’,

it was counted toward the variable indicating whether

the child experiences violent discipline.

Regarding the instance ‘FCF’, the modules re-

lated to different domains of difficulty were analyzed,

such as Seeing (‘FCF6’), Hearing (‘FCF8’), Mobil-

ity (‘FCF10’ to ‘FCF15’), Self-Care (‘FCF16’), Com-

munication/Comprehension (‘FCF17’ and ‘FCF18’),

Learning (‘FCF19’), Remembering (’‘FCF20’), At-

tention and Concentration (‘FCF21’), Coping with

Change (‘FCF22’),Controlling Behaviour(‘FCF23‘),

Relationships (‘FCF24’), and Emotions such as Anx-

iety and Depression (‘FCF25’ and ‘FCF26’). The

responses for the modules were: 1) no difficulty, 2)

some difficulty, 3) a lot of difficulty, and 4) total in-

ability, except in the domain of emotions, where the

options were: 1) daily, 2) weekly, 3) monthly, 4) a

few times a year, and 5) never. A child was consid-

ered to have a disability if they reported ’a lot of dif-

ficulty’ or ’total inability’ in any function. In the case

of emotions, only daily difficulties were considered a

disability.

With the data already normalized and translated,

the first column of both datasets, which serves as an

identifier, was used to merge the responses regarding

disability and violence. Thus, if a caregiver answered

‘yes’ to any of the violence modules and indicated ‘a

lot of difficulty’ or ‘inability’ for any of the disability

modules, this information was aggregated to estimate

how many children per country suffer from both dis-

ability and experiences with violent discipline.

Finally, the desired target variable for prediction

was selected, which in this case was disciplinary vio-

lence.

For the execution of the machine learning models,

the data were divided into training and testing sets,

with the test set representing 20% of the total. Sub-

sequently, undersampling was applied to the majority

class, randomly selecting data from this class for re-

moval until the numbers were equal to those of the

minority class. The data from the majority class that

were to be discarded were added to the test set.

To optimize the performance of machine learning

models, multiple algorithms (Random Forest, Deci-

sion Tree, Support Vector Machine, XGBoost, and

Neural Network) were tested with their respective hy-

perparameter optimizations. The search for the best

hyperparameter combinations was performed using

the random search approach (RandomizedSearchCV),

with stratified cross-validation to ensure the robust-

ness of the evaluation. The search space was adjusted

individually for each model with specific intervals of

relevant hyperparameters. The best hyperparameters

found for each model were compared based on per-

formance metrics, including recall

12

, precision

13

, F1-

Score

14

, and accuracy.

All calculations were performed using Python li-

braries: Pandas (version 2.2.2), NumPy (version

2.1.1), Scikit-learn (version 1.5.1), Imbalanced-

learn (version 0.12.3), and Matplotlib (version

3.9.2). The tests were executed on a system with an

Apple M2 processor, 8 GB of RAM, and 8 CPU cores.

5 RESULTS

Figure 3 presents the results of the analyzed algo-

rithms, with SVM standing out for its superior per-

formance, achieving the highest values for precision,

recall, and F1-score. These results indicate effective-

ness in classifying both negative and positive cases.

However, despite the high precision, the model iden-

tified a significantly larger proportion of cases in the

‘did not experience disciplinary violence’ class com-

pared to the ‘experienced disciplinary violence’ class.

This discrepancy may be attributed to the imbalance

in the dataset.

Since the SVM, Random Forest and XGBoost

models exhibited the best results, with an F1-Score

of 80%, 76% and 72% for the ‘did not experience

disciplinary violence’ class and 78%, 75% and 70%

for the ‘experienced disciplinary violence’ class, we

conducted a SHAP analysis (in Figure 4) to better un-

derstand which attributes influenced the prediction of

disciplinary violence cases.

The SHAP assigns an importance value to each

feature based on its contribution to the prediction, us-

ing Shapley value theory to ensure a fair attribution.

In the SHAP plot, the most important variables are at

the top, while the less influential ones appear at the

bottom. Each point represents an observation, with

the color indicating the feature value: red for high val-

ues and blue for low values. The horizontal position

of each point reflects the magnitude of the feature’s

contribution, where positions further to the right indi-

cate a greater positive influence on the prediction that

the individual experienced disciplinary violence, and

to the left, a negative influence (i.e., a lower chance of

12

Recall =

T P

T P+FN

: Measures the model’s ability to cor-

rectly identify positive instances.

13

Precision =

T P

T P+FP

: Indicates the proportion of correct

positive predictions among all the positive predictions made

by the model.

14

F1-Score = 2 ×

Precision×Recall

Precision+Recall

: Combines precision

and recall into a single metric for balanced evaluation.

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

166

Figure 2: Number of children with disabilities experiencing violent discipline by country in the sixth round of MICS.

Figure 3: Analysis of metrics by algorithm.

experiencing disciplinary violence).

The analysis identified the 30 attributes that most

influence the prediction of disciplinary violence, pre-

sented in the image below:

• Child Needs Punish: This attribute refers to

caregivers’ belief that physical punishment con-

tributes to a child’s development. In the context

of this attribute, it is observed in image 5 that this

belief (indicated by the attribute to the right) is a

significant factor driving disciplinary violence, as

the SHAP values are all positive and quite con-

centrated. In contrast, the absence of this belief

(indicated by the attribute to the left) shows an op-

posite pattern: the values are all concentrated in

the negative region, indicating that the belief that

the child deserves to be punished is strongly asso-

ciated with the presence of disciplinary violence.

• FCD2A, FCD2B, and FCD2E:

The attributes ‘FCD2A’, ‘FCD2B’, and ‘FCD2E’

refer to non-violent forms of discipline, such as

preventing the child from doing something or tak-

ing away privileges (‘FCD2A’), explaining why

the child’s behavior was wrong (‘FCD2B’), and

offering alternatives to distract them (‘FCD2E’).

In the SHAP graph, the value 1.0 is assigned to

the use of these non-violent practices, while the

value 2.0 represents their opposite. It is observed

that these attributes are correlated with the use of

violent discipline, indicating that, even in con-

texts where non-violent discipline practices are

applied, they often coexist with harsher forms of

disciplinary violence. This phenomenon may be

associated with specific cultural and social fac-

tors. Similar results were found in the study by

Cuartas et al. (2019).

• Fertility Rate, Infant Mortality Rate, and GDP

per capita: The analysis of the attributes Fertil-

ity Rate and Infant Mortality Rate in the SHAP

graph reveals that higher rates are associated with

greater severe disciplinary violence, indicating

that countries facing these challenges encounter

social and economic difficulties, such as limited

access to healthcare and education services, favor-

ing strict disciplinary practices.

Using Machine Learning to Assess the Impact of Harsh Violent Discipline on Children and Adolescents in Low- and Middle-Income

Countries: A Comparative Analysis Focusing on Its Relationship with Disabilities

167

Figure 4: SHAP Analysis in XGBoost.

Figure 5: Analysis of the attribute child needs punish.

On the other hand, countries with lower rates tend

to have better access to family planning, pub-

lic health, and contraceptive methods (Aarssen,

2005), which is associated with more accessible

education and professional development opportu-

nities, promoting more constructive disciplinary

approaches.

The analysis of GDP per capita reinforces this

perspective: countries with higher income exhibit

lower fertility and infant mortality rates, reflecting

better living conditions and access to healthcare

and education services, as well as more effective

parenting practices and less severe discipline. In

contrast, countries with lower GDP per capita face

social challenges that result in stricter discipline.

Thus, fertility rate, infant mortality, and GDP per

capita not only reflect family dynamics but also

the social and economic conditions that impact

child disciplinary practices.

• fs age: The analysis of the fs age attribute, which

represents the age of the child being analyzed, re-

veals a clear trend in the SHAP graphs and in the

violin plot (Figure 6). The violin plot, covering

ages from 5 to 14, shows that as age increases,

particularly from 10 years onward, the values tend

to become negative, signifying a reduced like-

lihood of experiencing severe violent discipline.

This relationship suggests that younger children,

represented by values more to the left on the

graph, are more vulnerable to harsh disciplinary

practices, which can be visualized by a greater

concentration of positive SHAP values indicating

violent discipline. In contrast, those over 10 years

old tend to be in contexts where disciplinary ap-

proaches may be more positive or constructive.

This pattern can be attributed to several factors.

Older children generally have a greater capacity

for communication and understanding, allowing

parents or guardians to adopt discipline strategies

that are more dialogue-oriented and educational,

rather than resorting to violence. Additionally, as

children grow, family dynamics and expectations

regarding behavior may change, resulting in a re-

duced need for severe disciplinary measures. The

violin plot effectively illustrates these shifts, high-

lighting the need for targeted interventions to pro-

tect younger children who are more susceptible to

harsh discipline.

• Male Life Expectancy and Female Life Ex-

pectancy: The analysis of the data reveals that

male life expectancy and female life expectancy

are associated with complex patterns of discipline.

Higher life expectancies, located to the left in the

SHAP graph, suggest a lower probability of vi-

olent discipline, reflecting access to better social

and health resources. Conversely, lower life ex-

pectancies, positioned to the right in the graph,

indicate a possible association with an increase in

violent discipline, suggesting that social and eco-

nomic challenges contribute to harsher practices.

The study by Hendricks et al. (2013) confirms that

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

168

Figure 6: Analysis of the attributes age of the child.

severe violent discipline is negatively related to

the Human Development Index (HDI) and life ex-

pectancy; the lower these indices, the higher the

incidence of reports of violence. This underscores

life expectancy as an indicator not only of health

but also of the social conditions that impact family

discipline.

• Sex: The analysis of the sex attribute, which rep-

resents the child’s gender, reveals that boys have

a significantly higher probability of suffering vio-

lent discipline (1.0) compared to girls (2.0). This

result suggests that social norms and cultural ex-

pectations related to gender may influence disci-

plinary practices.

Additionally, similar findings were reported in the

article by Emerson and Llewellyn (2021) and also

in data from the MICS in the article by Lans-

ford et al. (2010), corroborating the observation

that boys are more subjected to severe disciplinary

methods. These disparities in disciplinary experi-

ences reflect not only gender socialization but can

also impact the emotional and psychological de-

velopment of children.

• num 5 17, num under5, num hh members:

The analysis of data regarding the number of chil-

dren aged 5 to 17 years, children under 5 years,

and the number of household members reveals

significant patterns related to violent discipline.

Fewer numbers of children and household mem-

bers are associated with a reduction in the likeli-

hood of violent discipline.

The presence of a single child aged 5 to 17 years

and the absence of children aged 0 to 5 years cor-

relate negatively with violent discipline. House-

holds with 2 to 5 members also exhibit a similar

trend, suggesting that smaller families foster en-

vironments less prone to severe disciplinary prac-

tices.

Conversely, an increase in the number of chil-

dren and household members is associated with

a higher likelihood of violent discipline, indicat-

ing that larger families may face challenges that

lead to stricter disciplinary practices, which may

be related to the fertility rate attribute.

These results highlight the importance of family

structure and social context in disciplinary expe-

riences, suggesting that smaller family configura-

tions may be better positioned to prevent violent

discipline.

• hh fridge, hh computer, hh internet: This

attribute analyzes the presence of household

appliances, including refrigerator (hh fridge),

computer (hh computer), and internet access

(hh internet) in the home. The analysis of SHAP

values indicates that the presence of these appli-

ances is associated with values close to neutral,

suggesting that they have a minimal impact on the

model’s predictions.

However, considering the minimal impacts, it is

observed that the absence of these appliances

seems to contribute more to the occurrence of vi-

olent discipline than their presence. This sug-

gests that homes without access to these ameni-

ties may be associated with more challenging so-

cial and economic conditions, as discussed in item

5, which in turn may lead to stricter disciplinary

practices, as previously discussed in earlier sec-

tions.

• fs education level, mother education level,

and father education level: This attribute

evaluates the highest educational level achieved

by the child, as well as the educational levels

of the caregiver and the guardian. The analysis

of SHAP values indicates an inverse correlation

between education level and the probability of

experiencing violent discipline. Children with

higher education levels, as well as those whose

parents have higher education levels, tend to have

a significantly lower probability of experiencing

violent discipline compared to those with lower

education levels.

This behavior suggests that factors associated

with schooling, such as greater knowledge and

communication skills, may contribute to a re-

duced risk of exposure to violent disciplinary

practices. Additionally, higher education levels

may be related to a family environment that val-

ues more positive and constructive disciplinary

methods, resulting in less reliance on severe dis-

ciplinary practices.

• MA2 group encoded, MA1, and natu-

ral mother lives hh: The attributes ‘MA1’,

Using Machine Learning to Assess the Impact of Harsh Violent Discipline on Children and Adolescents in Low- and Middle-Income

Countries: A Comparative Analysis Focusing on Its Relationship with Disabilities

169

which refers to the marital status of the inter-

viewed woman, and ‘MA2’, which indicates

the current age of the husband, demonstrate a

significant relationship with the occurrence of

violent discipline.

The analysis of SHAP values reveals that married

women are less likely to adopt violent disciplinary

practices compared to those in long-distance rela-

tionships or living with a partner.

Regarding the husband’s age (‘MA2’), it is ob-

served that the younger the husband, the greater

the likelihood of violent discipline occurring.

This correlation may suggest that younger hus-

bands tend to have less experience with parenting

and family dynamics, which can result in a greater

use of violent disciplinary practices.

Furthermore, the attribute ‘natu-

ral mother lives hh’, which indicates the

presence of the biological mother in the house-

hold, is associated with a lower probability of

experiencing violent discipline. The presence of

the biological mother may be related to a more

stable family environment, which can contribute

to the reduction of violent disciplinary practices.

• number of disabled domains: This attribute

is the main focus of this study, gathering

information on the following domains: see-

ing, hearing, mobility, self-care, communica-

tion/comprehension, learning, remembering, at-

tention and concentrating, relationships, coping

with change, affect (anxiety and depression) and

controlling behaviour. The objective is to estimate

whether an increase in these disabilities is related

to an increased likelihood of experiencing violent

discipline.

The analysis of the SHAP graphs indicates that

the absence of difficulty domains has a negative

impact on the occurrence of violence, while an

increase in the number of domains is associated

with a slight rise in the probability of experiencing

violent discipline. Supported by this observation,

the violin plot (Figure 7) shows that for individu-

als with no domains of difficulty, 50% of the data

(from the first quartile to the third quartile) are

concentrated in negative values, reinforcing this

lower probability. As the number of deficiency

domains increases, especially in the range of 1 to

3 domains, the quartiles are closer to the positive

median, suggesting a growing association with se-

vere violent disciplinary practices. This change

in distribution reflects a correlation between the

number of difficulties domains and the increased

likelihood of exposure to severe disciplinary mea-

sures, with the median shifting to higher levels as

Figure 7: Analysis of the number of difficulty domains.

Figure 8: Analysis of disabilities and difficulty domains.

the number of domains increases. This data indi-

cates that the presence of multiple domains may

be associated with a higher risk of experiencing

violent disciplinary practices.

• fsdisablity and behaviour control disab: The

analyzed attributes refer to the presence of at

least one type of disability in the child (‘fsdis-

ability’), encompassing seeing, hearing, mobility,

self-care, communication/comprehension, learn-

ing, remembering, attention and concentrating,

relationships, coping with change, affect (anxi-

ety and depression) and controlling behaviour do-

mains. A specific attribute is dedicated to disabil-

ities related to the domain controlling behaviour

(‘behaviour control disab’).

The analysis of the SHAP graphs indicates that

the absence of disabilities is associated with a de-

creased likelihood of experiencing violent disci-

pline. In contrast, the presence of at least one dis-

ability correlates with a significant increase in the

probability of suffering from violent disciplinary

practices.

As shown in Figure 8, when there is no disability,

the SHAP values are predominantly negative, sug-

gesting a lower likelihood of experiencing violent

discipline. However, the introduction of difficulty

domains particularly those related to controlling

behaviour, results in a notable shift toward pos-

itive SHAP values. This trend highlights that the

presence of any functioning domain is linked to an

elevated risk of experiencing severe disciplinary

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

170

methods. This data underscores the need for ap-

propriate interventions and specialized support for

children with disabilities.

6 DISCUSSION

This research aimed to investigate the importance of

attributes related to various difficulties domains, in-

cluding seeing, hearing, mobility, self-care, commu-

nication/comprehension, learning, remembering, at-

tention and concentrating, relationships, coping with

change, affect ( anxiety and depression ) and espe-

cially controlling behaviour. The graphical analy-

sis of proportions reveals a significant correlation be-

tween the incidence of violent discipline in children

and the presence of disabilities.

The data indicate that, proportionally, a larger

number of children facing violent discipline have

some form of disability compared to those who do

not. This observation suggests that children with dis-

abilities, particularly those related to behavior con-

trol, face additional challenges that make them more

vulnerable to harsher disciplinary methods.

Controlling behaviour difficulties in children may

manifest in actions such as lying, fighting, bullying,

running away from home, or skipping school, lim-

iting their ability to interact appropriately with oth-

ers. These challenging behaviors can lead caregivers

to believe in the necessity of punishment, exacerbat-

ing severe discipline. This dynamic may result in

a vicious cycle, where the lack of adequate support

worsens the situation, leading to disciplinary practices

that are not only inappropriate but also harmful to the

emotional and social development of children (Sin-

horinho and de Moura, 2021).

Furthermore, the presence of disabilities may be

associated with difficulties in socialization and in-

creased levels of anxiety and depression, affecting in-

teractions with peers and adults. In this context, se-

vere discipline not only fails to address challenging

behaviors constructively but may also intensify the

vulnerability of these children, necessitating interven-

tions that promote social and emotional support.

The results also demonstrated that the presence of

multiple difficulties domains further exacerbates this

correlation. Although this research focused on dis-

abilities, socioeconomic factors, such as the level of

development of the country, also play a significant

role. Less developed countries or those with weaker

economies, characterized by lower life expectancy,

higher infant mortality rates, lower GDP per capita,

and higher fertility rates, show a greater tendency to-

wards the application of severe violent discipline.

Additionally, the belief that violence is necessary

to educate and raise a child was strongly correlated

with the application of severe disciplinary methods.

This cultural perception can perpetuate cycles of vi-

olence, making it essential to promote educational

practices that challenge these beliefs.

To enrich this analysis, we employed various ma-

chine learning algorithms. These methods allowed for

the visualization of the relative importance of each at-

tribute in the context of violent discipline. These tech-

niques highlighted the complexity of interactions be-

tween the variables and facilitated the identification of

patterns that might have gone unnoticed in traditional

analyses.

These results demonstrate the urgency of edu-

cational practices that promote inclusion and raise

awareness about the specific needs of children with

disabilities. The adoption of more empathetic disci-

plinary methods and the implementation of interven-

tions focused on social skills may be essential to re-

ducing the incidence of violent discipline and ensur-

ing a safer and more supportive environment for chil-

dren.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the National Coun-

cil for Scientific and Technological Development of

Brazil (CNPq – Code: 311573/2022-3), the Co-

ordination for the Improvement of Higher Educa-

tion Personnel - Brazil (CAPES - Grant PROAP

88887.842889/2023-00 - PUC/MG, Grant PDPG

88887.708960/2022-00 - PUC/MG - Informatics and

Finance Code 001), the Foundation for Research

Support of Minas Gerais State (FAPEMIG – Codes:

APQ-03076-18 and APQ-05058-23). The work was

developed at the Pontifical Catholic University of Mi-

nas Gerais, PUC Minas, in the Applied Computa-

tional Intelligence Laboratory – LICAP.

REFERENCES

Aarssen, L. W. (2005). Why is fertility lower in wealthier

countries? the role of relaxed fertility-selection. Pop-

ulation and Development Review, 31(1):113–126.

Bhatia, A., Davey, C., Bright, T., Rotenberg, S., Eldred, E.,

Cappa, C., Kuper, H., and Devries, K. (2023). In-

equities in birth registration, violent discipline, and

child labour by disability status and sex: Evidence

from the multiple indicator cluster surveys in 24 coun-

tries. PLOS Glob. Public Health, 3(5):e0001827.

Cappa, C. and Khan, S. M. (2011). Understanding care-

givers’ attitudes towards physical punishment of chil-

Using Machine Learning to Assess the Impact of Harsh Violent Discipline on Children and Adolescents in Low- and Middle-Income

Countries: A Comparative Analysis Focusing on Its Relationship with Disabilities

171

dren: evidence from 34 low- and middle-income

countries. Child Abuse Negl., 35(12):1009–1021.

Cecilie Bingham, Linda Clarke, E. M. M. V. d. M. (2013).

Towards a social model approach? : British and

dutch disability policies in the health sector compared

— emerald insight. https://www.emerald.com/insight/

content/doi/10.1108/PR-08-2011-0120/full/html.

Cuartas, J., Mccoy, D., Rey-Guerra, C., Britto, P., Beatriz,

E., and Salhi, C. (2019). Early childhood exposure

to non-violent discipline and physical and psycholog-

ical aggression in lmics: national, regional, and global

prevalence estimates.

Cuartas, J., McCoy, D. C., Rey-Guerra, C., Britto, P. R.,

Beatriz, E., and Salhi, C. (2018). Early childhood

exposure to non-violent discipline and physical and

psychological aggression in low- and middle-income

countries: National. regional, and global prevalence

estimates, Child Abuse & Neglect, 92(063).

Emerson, E. and Llewellyn, G. (2021). The exposure

of children with and without disabilities to violent

parental discipline: Cross-sectional surveys in 17

middle- and low-income countries. Child Abuse &

Neglect, 111:104773.

Fang, Z., Cerna-Turoff, I., Zhang, C., Lu, M., Lachman,

J. M., and Barlow, J. (2022). Global estimates of vi-

olence against children with disabilities: an updated

systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet.

Child & adolescent health, 6(5):313–323.

Farias, N. and Buchalla, C. M. (2005). A classificac¸

˜

ao in-

ternacional de funcionalidade, incapacidade e sa

´

ude

da organizac¸

˜

ao mundial da sa

´

ude: conceitos, usos

e perspectivas. Revista brasileira de epidemiologia,

8(2):187–193.

Hendricks, C., Lansford, J. E., Deater-Deckard, K., and

Bornstein, M. H. (2013). Associations between child

disabilities and caregiver discipline and violence in

low- and middle-income countries. Child Develop-

ment, 85(2):513–531.

Jean A Pardeck, J. W. M. (2012). Disability issues for social

workers and human services professionals.

Lansford, J. E., Alampay, L. P., Al-Hassan, S., Bacchini, D.,

Bombi, A. S., Bornstein, M. H., Chang, L., Deater-

Deckard, K., Di Giunta, L., Dodge, K. A., Oburu, P.,

Pastorelli, C., Runyan, D. K., Skinner, A. T., Sorbring,

E., Tapanya, S., Tirado, L. M. U., and Zelli, A. (2010).

Corporal punishment of children in nine countries as

a function of child gender and parent gender. Int. J.

Pediatr., 2010:672780.

Linda L. Dahlberg, Etienne G. Kru (2006). Violence a

global public health problem. https://www.scielosp.

org/pdf/csc/2006.v11n2/277-292/en. (Accessed on

04/28/2024).

Pace, G. T., Lee, S. J., and Grogan-Kaylor, A. (2019).

Spanking and young children’s socioemotional devel-

opment in low- and middle-income countries. Child

Abuse Negl., 88:84–95.

Sinhorinho, S. M. and de Moura, A. T. M. S. (2021). Uso de

disciplina violenta na inf

ˆ

ancia – percepc¸

˜

oes e pr

´

aticas

na estrat

´

egia sa

´

ude da fam

´

ılia.

Sinhorinho, S. M. and Moura, A. T. M. S. d. (2022). Uso de

disciplina violenta na inf

ˆ

ancia: percepc¸

˜

oes e pr

´

aticas

na estrat

´

egia sa

´

ude da fam

´

ılia. Revista Brasileira de

Medicina de Fam

´

ılia e Comunidade, 17(44):2835.

Talo, S. A. and Ryt

¨

okoski, U. M. (2016). BPS-ICF model, a

tool to measure biopsychosocial functioning and dis-

ability within ICF concepts: theory and practice up-

dated. Int. J. Rehabil. Res., 39(1):1–10.

UNICEF (2021). Seen, counted, included: Using

data to shed light on the well-being of children

with disabilities [en/ar] - world — reliefweb.

https://reliefweb.int/report/world/seen-counted-

included-using-data-shed-light-well-being-children-

disabilities.

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

172