Evaluating the Effect of Practice Quizzes on Exam Performance in an

Advanced Software Testing Course

Lindsey Nielsen

a

, Sudipto Ghosh

b

and Marcia Moraes

c

Department of Computer Science, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, U.S.A.

Keywords:

Practice Quizzes, Feedback, Software Testing Course, Difficulty Level.

Abstract:

Self-testing is considered to be an effective educational practice for enhancing student performance and long-

term retention. Various studies have investigated the impact of using practice quizzes with different levels of

difficulty and varying detail in the provided feedback, but they tend to investigate these factors separately and

in K-12 and lower division computer science courses as opposed to upper level courses. Our study shows that

practice quizzes can significantly improve students’ exam grade in an advanced computer science course in

software testing. We evaluate and gather student perceptions on two different systems, MILAGE LEARN+ and

Canvas Learning Management System. Over the semester, students took five quizzes via MILAGE LEARN+

or Canvas, each with the option of beginner and intermediate difficulty levels. Students using MILAGE

LEARN+ received detailed explanations for their selected answers, while Canvas quizzes only showed them

which answers were correct (or incorrect). Students focusing on intermediate-level quizzes performed the best

on exams, followed by those engaging with both levels and finally, those focusing on beginner-level quizzes.

The practice quizzes improved student exam grades in the current semester compared to the previous semester

which did not include practice quizzes. MILAGE LEARN+ received mixed reviews but was generally viewed

positively. However, students preferred Canvas for future use.

1 INTRODUCTION

Self-testing is a well-established educational practice

that significantly enhances students’ performance and

long-term retention of material. Research has con-

sistently shown that regular self-testing not only ass-

esses students’ knowledge but also reinforces learn-

ing through the retrieval practice effect (Moraes et al.,

2024; YeckehZaare et al., 2022; Lyle et al., 2020).

This phenomenon of strengthening memory by recall-

ing information motivated us to incorporate practice

quizzes into an advanced (senior-level) software test-

ing course (CS415) at Colorado State University. The

purpose of the course was to teach students in-depth

knowledge and skills in rigorous testing methodolo-

gies, ensuring the reliability, performance, and se-

curity of complex software systems. Students were

tested on their abilities to understand software testing

concepts and procedures through assignments and ex-

ams. There was also a semester-long software devel-

opment project where student teams put their newly

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0141-8375

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6000-9646

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9652-3011

acquired software testing skills into practice.

Practice quizzes serve as effective learning tools

by engaging students with the course material (Mur-

phy et al., 2023; Little and Bjork, 2015). They en-

courage students to regularly review and apply their

knowledge, promoting a deeper understanding and re-

tention. Students can use them to gauge their level of

understanding before an exam to know what areas to

work on. Varying the difficulty level in the quizzes

can challenge students to think critically about the

subject and deeply understand it (Scully, 2017).

We incorporated the practice quizzes on two dif-

ferent platforms: MILAGE LEARN+ and Canvas.

MILAGE LEARN+ is an interactive mobile learning

application used to enhance student’s education ex-

perience through quizzes, worksheets, feedback, self-

grading and flexibility of usage (Figueiredo et al.,

2020; Dorin et al., 2024). Students can utilize it in any

location with internet access to complete quizzes and

assignments as part of their daily activities. Canvas

(Oudat and Othman, 2024) is a learning management

system that allows students to access course materi-

als, complete quizzes and also has mobile accessibil-

ity. Many students participating in this study were

208

Nielsen, L., Ghosh, S. and Moraes, M.

Evaluating the Effect of Practice Quizzes on Exam Performance in an Advanced Software Testing Course.

DOI: 10.5220/0013199800003932

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2025) - Volume 1, pages 208-215

ISBN: 978-989-758-746-7; ISSN: 2184-5026

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

new to MILAGE LEARN+, but frequently used Can-

vas as it is the learning management system of the uni-

versity. On MILAGE LEARN+ we included detailed

feedback with explanations for every selected answer,

while on Canvas the feedback just notified the student

whether the selected answer was correct or not. Stu-

dents’ perceptions of the two platforms were gathered

at the end of the semester.

Research on the MILAGE LEARN+ platform

within the context of computer science education is

lacking. Previous studies have primarily focused on

using it as an alternative testing tool to assess stu-

dent knowledge and motivation (Dorin et al., 2024).

However, there has been no investigation into the role

of feedback within this platform for enhancing prac-

tice and learning. Our study provides new insights

into the effectiveness of feedback mechanisms in MI-

LAGE LEARN+ in improving student exam perfor-

mance in computer science.

While elements like feedback and varying diffi-

culties are well-researched (Butler and Winne, 1995;

R

¨

uth et al., 2021; Sch

¨

utt et al., 2024), their integration

into a platform like MILAGE LEARN+ is relatively

new (Figueiredo et al., 2020). Previous studies have

found that frequent classroom quizzing with feedback

significantly improves student learning (McDermott

et al., 2014). Moreover, students who participated

in multiple-choice quizzing showed better exam per-

formance compared to those who either didn’t partic-

ipate or participated in short answer quizzing (Mc-

Dermott et al., 2014). Combining these elements

can provide a new understanding of how feedback

and difficulty levels can enhance exam performance.

By studying students’ selection of difficulty level and

their performance on midterm and final exams, we

can observe how these factors impact the strengthen-

ing of their knowledge. The study aims to answer the

following research questions:

• RQ1. How do practice quizzes impact exam

scores?

• RQ2. How do varying difficulties on practice

quizzes impact exam scores?

• RQ3. How does the level of detail in feedback on

practice quizzes impact exam scores?

We hypothesized that incorporating practice

quizzes would enhance exam scores by allowing stu-

dents to practice and test their knowledge before the

exams. Engaging with quizzes of varying difficulty

levels by learning and reflecting with beginner-level

quizzes and then applying the newly acquired skills

with intermediate-level quizzes should lead to greater

improvements in exam scores compared to working

with just one difficulty level throughout the semester.

Providing more detailed feedback should make stu-

dents perform better on exams because it would help

students reflect better on the material.

2 RELATED WORK

Early studies laid the groundwork for showing the im-

portance of practice quizzes and retrieval in academia

for student learning and retention (Roediger and But-

ler, 2011). The timing of quizzes can affect stu-

dent motivation, engagement, and knowledge reten-

tion (Case and Kennedy, 2021). Frequent in-class

quizzes, both pre-lecture and post-lecture, have been

shown to significantly improve student lesson prepa-

ration, participation, and knowledge retention (Case

and Kennedy, 2021). More recent research (Moraes

et al., 2024) explored the use of practice quizzes as

learning tools to improve learning in an introductory

computer programming course.

Students report that MILAGE LEARN+ is both

motivating and enjoyable, serving as a great tool

for studying course materials (Figueiredo et al.,

2023). Additionally, teachers have observed that

it effectively promotes student motivation and self-

regulation (Almeida et al., 2022). Recently (Dorin

et al., 2024) showed that computer science students

scored higher on MILAGE LEARN+ than on Canvas,

because of its motivating features, peer review sys-

tem, and the ability to incorporate a versatile range of

question types, including graphs, pictures, and code.

Studies such as (Shute, 2008; R

¨

uth et al., 2021)

focused on how different types of feedback encour-

age students to learn. Including additional infor-

mation other than just noting whether the answer

was correct or incorrect improved students’ learning

(Shute, 2008). Tailored feedback substantially im-

proved learning outcomes by providing students with

specific insights into their performance, reinforcing

the importance of constructive feedback in educa-

tional contexts (R

¨

uth et al., 2021). We build upon

these research and investigate how different platforms

and different styles of feedback can influence exam

grades. Moreover, we also study how the students’

perceptions on the platforms can be influenced by the

amount of feedback being given.

Adaptive quizzes that tailor quiz difficulty to

individual student performance were found to in-

crease motivation, engagement, and learning out-

comes (Ross et al., 2018). These findings highlight

how well-designed quizzes can make a big differ-

ence in helping students learn more effectively. Mul-

tiple choice questions can be considered more chal-

lenging than true/false questions due to the level of

Evaluating the Effect of Practice Quizzes on Exam Performance in an Advanced Software Testing Course

209

cognitivity since a student would need to answer a

question with more options rather than just a 50/50

guess with true/false questions (McDermott et al.,

2014). Multiple-choice questions can assess higher-

order thinking skills when well-designed (Scully,

2017), while true/false questions are often used for

basic recall (Uner et al., 2021). Our study also used

these two types of questions.

3 APPROACH

The overarching goal of this study was to gain an

understanding on how students use practice quizzes,

feedback and varying levels of difficulties to improve

their comprehension of software testing demonstrated

through exam grades. We now describe the study

participants, practice quizzes, data collection method,

and data analysis techniques.

Participants. There were 118 students (undergrad-

uate and graduate) in the CS415 course in the Spring

2024 semester who participated in the research. The

participants, all over 18 years old, are majors in com-

puter science or related engineering fields.

Practice Quizzes. There were five practice quizzes

in total, with about two weeks to complete each one.

The topics included input space partitioning, graph

coverage, mutation analysis, dataflow analysis, test

paths, finite state machines, and activity diagrams.

While each quiz was graded based on correctness

and appropriate feedback was provided, the grades

recorded in the grade book were solely based on par-

ticipation. We wanted the students to engage and

practice without having to worry about getting a bad

grade while they were still learning. The quizzes were

identical on both the systems, and students were lim-

ited to one attempt per quiz. However, they were al-

lowed to try both the beginner and intermediate levels

of difficulty on both platforms. The quizzes were sim-

ilar to the questions in the midterm and final exams.

The questions were designed to be more than just

definition questions. Instead, they involved challeng-

ing applications of the topics as seen in Figures 1 and

2. Despite being presented in a true/false or multiple

choice format, the questions incorporated the com-

plexity of short answer or coding questions. Students

had to solve the problem and select an answer out

of the given choices, which required them to engage

with the material, think critically about how to apply

what they learned, assess their level of comprehension

of the materials, and identify areas for further study.

Figure 1: Example of an Beginner Difficulty Question.

Figure 2: Example of an Intermediate Difficulty Question.

Difficulty Levels. Students could choose the level

of difficulty from two options: beginner difficulty,

which included true/false questions, and intermediate

difficulty, which included multiple-choice questions.

They had to select at least one difficulty level in each

quiz to get participation credit. Some students chose

to do both while others just chose one.

Figure 1 shows a beginner level question. Stu-

dents had to draw a graph based on the specification,

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

210

find the test paths that achieve edge coverage, and ap-

propriately choose true or false. Figure 2 shows an

intermediate level question containing code and a fi-

nite state machine diagram. Students had to identify

labels for the states and transitions of the diagram and

choose the answer containing the correct labels.

Feedback. When a student answered a question in-

correctly, MILAGE LEARN+ displayed the correct

answer and an explanation as shown in Figures 3 and

4. The corresponding messages in Canvas for were

“Correct answer: False” and “Correct answer: b”.

Figure 3: Beginner Level Question Detailed Feedback.

Figure 4: Intermediate Level Question Detailed Feedback.

Data Collection. We collected exam grades from

both the previous semester, where no practice quizzes

were given, to establish a baseline for student perfor-

mance, and the Spring 2024 semester, for compar-

ison. Although the exams in 2023 and 2024 were

designed to be similar, there was one difference. In

2023, students faced a single comprehensive final

exam, whereas in 2024, the assessment was divided

into three separate exams. The questions were either

identical to the ones in 2023, or slightly modified in

terms of values, while keeping the topic, nature of the

question, and level of difficulty the same (e.g., using

a different program fragment or finite state machine).

We kept track of which quizzes each student com-

pleted, noting whether they chose beginner, interme-

diate, or both difficulty levels, and whether they used-

Canvas or MILAGE LEARN+. To understand their

experiences better (Thierbach et al., 2020), we asked

students to fill out a survey about their overall percep-

tions towards the platforms and the practice quizzes.

The survey included a question on how often they

used MILAGE LEARN+ and a series of questions

on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to

5 (strongly disagree) regarding their motivation and

feelings about its usage. These questions included

statements such as “My level of frustration while us-

ing MILAGE LEARN+ was minimal to none” and “I

prefer quiz taking in Canvas compared to MILAGE

LEARN+”. It also included statements such as “I

would use this tool again in the future” or “Using this

tool could have benefited me in the past” to compile

students’ viewpoints on the platforms. The final ques-

tion of the survey was, “If there is anything else you

would like to tell us about your experience using MI-

LAGE LEARN+ please write it here:”.

Data Analysis. We compared the exam grades from

the current semester with those from the previous

semester taking into account the performance of dif-

ferent groups, such as those who completed beginner,

intermediate, or both levels of quizzes. We also ana-

lyzed the grades of students who were given detailed

feedback vs correct/incorrect feedback on the differ-

ent platforms. We performed a t-test to find the p

value of whether or not the practice quizzes had a sta-

tistically significant impact on student exam grades.

We attempted to understand the reasons and factors

that influenced the outcomes.

4 RESULTS

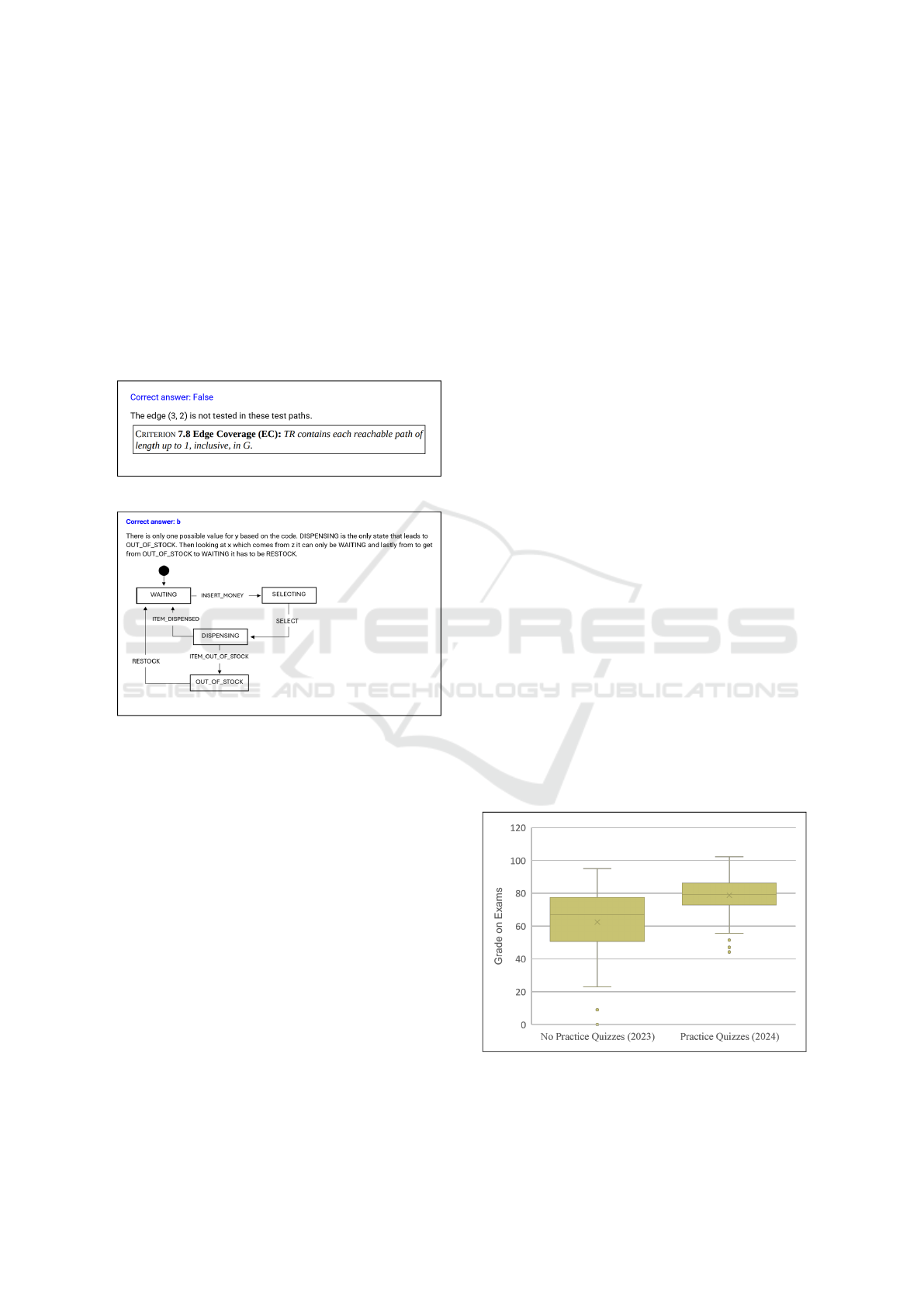

Figure 5 shows a boxplot with the min, lower quartile,

median, upper quartile, and max scores of the exam

grades for each student from 2023 (which excluded

the quizzes) and 2024 (which included the quizzes).

Figure 5: Effect of Practice Quizzes on Exam Grades.

There were 56 and 118 students enrolled in 2023

and 2024 with average exam scores of 62.46% and

Evaluating the Effect of Practice Quizzes on Exam Performance in an Advanced Software Testing Course

211

78.79% respectively. An unpaired t-test was con-

ducted on the two semesters, resulting in a p-value

less than 0.001, confirming the statistical significance

of the results. Thus, the addition of the practice

quizzes had a significant increase on the students’

grades on the exams.

Figure 6: Effect of Practice Quiz Difficulty Groups on

Exam Grades.

Figure 6 shows the exam scores for each of

the three groups corresponding to: beginner prac-

tice quizzes only, intermediate practice quizzes only,

and both beginner and intermediate practice quizzes.

From the 118 students who took the practice quizzes,

22 students chose to complete only the beginner dif-

ficulty practice quizzes and they had an average score

of 76.34% on the midterm and final exams. The 3

students who chose to only complete the intermedi-

ate difficulty practice quizzes, had an average score of

90.19%. The rest of the students attempted both diffi-

culty levels of each practice quiz and had an average

score of 79.01% on the exams. Note that a curve was

applied to the score, which resulted in some students

getting slightly higher than 100% in the exams.

Figure 7 shows the min, lower quartile, median,

upper quartile and max exam scores for those who

used MILAGE LEARN+, which provided detailed

feedback, versus those who used Canvas, which pro-

vided only correct/incorrect feedback. The average

score on the exams was 77.18% for the 30 students on

MILAGE LEARN+ and 80.15% for the 88 on Canvas.

Figure 7: Effect of Practice Quiz Platform on Exam Grades.

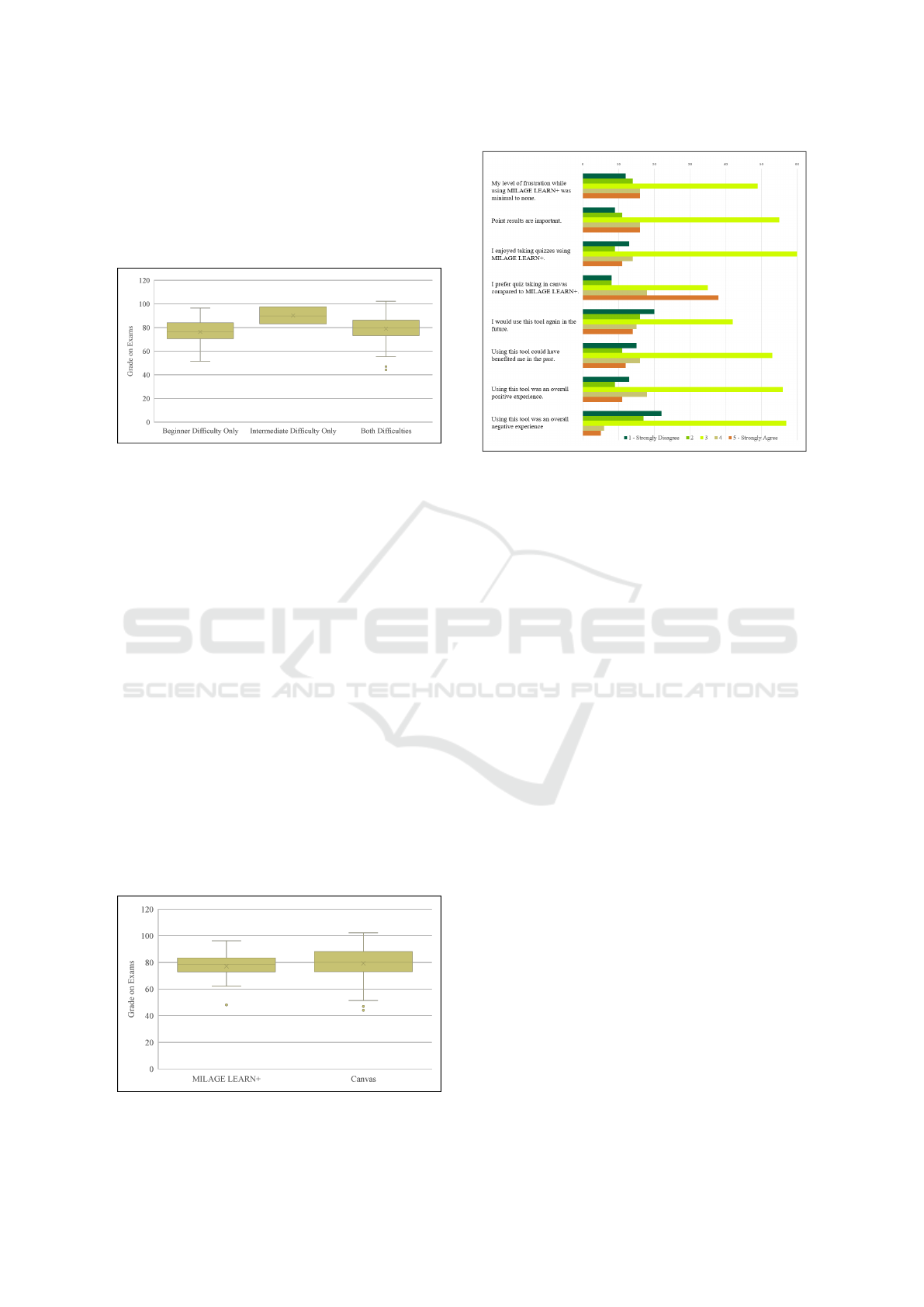

Figure 8: Student Responses on Survey Questions.

Figure 8 shows the students’ perceptions on the

two platforms and their feelings about the prac-

tice quizzes. Notable observations include the pre-

dominantly neutral opinions regarding the quizzes

and platforms. Additionally, students expressed a

preference for taking quizzes on Canvas over MI-

LAGE LEARN+. They also stated that while they

were aware that they received participation points in

the grade book, they were nevertheless interested in

knowing which questions they had answered correctly

or incorrectly.

5 DISCUSSION

In this section we analyze the results, answer the re-

search questions, and discuss the limitations.

RQ1. We believe that students who had practice

quizzes performed better than those who didn’t have

these quizzes because we created the quizzes to make

the students think critically about the questions in

order to select the correct answer. Moreover, the

practice quizzes included self-testing on topics that

were included on the exams. Either way, the practice

quizzes had a positive impact on the students’ overall

comprehension and exam performance. These find-

ings align with previous research demonstrating that

practiced recall is crucial for students learning and

improve student performance (Roediger and Butler,

2011; YeckehZaare et al., 2022; YeckehZaare et al.,

2019; Moraes et al., 2024).

RQ2. Students who only completed the interme-

diate quizzes throughout the semester did better on

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

212

the exams probably because they were self-selected.

They challenged themselves with the questions that

required a higher cognitive demand, which caused

stronger connections to the material. They were well

prepared and understood the content for the exams.

Students who only did the beginner difficulty did

the worst on the exams. This could be attributed

to the limited scope and lower cognitive demands of

true/false questions, which may not have sufficiently

challenged the students or promoted critical thinking.

Thus, these students lacked the depth of understand-

ing required to excel in complex exam questions.

Students who did both difficulties of practice

quizzes scored in between. They likely had the bene-

fit of having their learning of the materials reinforced

and, consequently, had a high average score than stu-

dents who just practiced the beginner level. Fig-

ure 6 shows the maximum high score of those who

completed both difficulties was 102.25% while the

high score for those who only did the intermediate

difficulty was 97.50%. This suggests that engaging

with a variety of quiz difficulties might foster a more

comprehensive understanding, allowing students to

achieve higher overall scores.

The group of students who only practiced the in-

termediate quizzes consisted of just 3 students, the

beginner-only group had 22, and the both difficulty

group had 93 students. This vast difference in group

sizes can cause significant variability and potential

bias in the results. It is noteworthy that all three

groups of students outperformed their 2023 counter-

parts in average exam scores. In 2023 the average

exam score was 62.45%, whereas the beginner, in-

termediate, and combined difficulties groups achieved

76.34%, 90.19%, and 79.01%, respectively. These re-

sults indicate that the inclusion of practice quizzes, re-

gardless of difficulty level, boosted exam scores com-

pared to the previous semester, which did not incor-

porate any practice quizzes. Moreover, the exposure

to different question types and difficulties could en-

hance critical thinking and problem-solving skills, ul-

timately benefiting exam performance.

More challenging questions like multiple choice

questions can be more beneficial to student compre-

hension than simpler questions like true/false ques-

tions (Burton, 2001; Scully, 2017). More open ended

questions and tasks aided in student learning better

than close ended ones (Sch

¨

utt et al., 2024; McDermott

et al., 2014). The questions on the practice quizzes in

our study caused students to think creatively and criti-

cally about the more advance topics of a software test-

ing course. This aligns with previous research where

more complex questions lead to higher comprehen-

sion among students. Also for the students who did

both levels of difficulty for each practice quiz could

also perform more spaced retrieval which can lead to

increased student learning (Lyle et al., 2020).

RQ3. Students who received detailed feedback on

MILAGE LEARN+ performed worse on exams while

the students who received feedback on Canvas per-

formed better on exams. Students could have relied

heavily on the provided guidance with the detailed

feedback practice quizzes instead of coming up with

the explanations on their own and deepening their un-

derstanding of a topic. In addition, the students were

already familiar with Canvas, which was also the plat-

form on which they took the exam. Thus, completing

the practice quizzes on Canvas as well could explain

why those students performed better.

While the average score from the Canvas feedback

group was higher than the average score from the MI-

LAGE LEARN+ feedback group, its range was larger

with a high of 102.25% and a low of 44.17%. For the

MILAGE LEARN+ group the high was 96.35% and

the low was 48.25%. In other words, short feedback

drove higher peak performance but led to greater dis-

parities among student outcomes. Detailed feedback

led to a more consistent level of understanding and

performance across the students. Perhaps the clar-

ity of brief feedback can provide a clear assessment

of the practice quizzes allowing students to acknowl-

edge where they went wrong. They could then use

that information to further their understanding of the

topic and help them perform better on exams by doing

their own research. On the other hand, students who

received brief feedback might not have gone the ex-

tra mile to find out the reasoning behind the questions

and this led to worse exam grades. This can explain

why brief feedback practice quizzes had higher highs

and lower lows on exams than detailed feedback.

Another possible reason is that providing short

feedback motivates some students (but not others)

to go and find out more information on their own,

such as from the lecture materials and other internet

sources. The former group tends to do better because

they have invested time in getting a deeper under-

standing of the materials, while the latter group con-

tinues to perform poorly because they have not un-

derstood the concepts even after taking the practice

quiz. This suggests that while brief feedback can be

highly effective for some students, detailed feedback

might offer a more balanced approach to overall stu-

dent learning. The choice can be determined by the

instructor’s goal for the student results.

In other research, feedback is recognized as a cru-

cial tool for student learning, with the type of feed-

back playing a significant role in student comprehen-

Evaluating the Effect of Practice Quizzes on Exam Performance in an Advanced Software Testing Course

213

sion (R

¨

uth et al., 2021). One study notes that de-

tailed feedback helps improve students’ learning but

ultimately the type of feedback did not matter (Shute,

2008). In our research, a similar trend emerged, with

students in both feedback groups performing well on

the exam. Both types of feedback proved beneficial in

their own unique ways for student learning and com-

prehension of the subject.

Survey. Students indicated a neutral perception of

MILAGE LEARN+. The neutrality could indicate a

mix of benefits of the applications and limitations that

were perceived by students. Students preferred to use

Canvas over MILAGE LEARN+ in the future because

our university uses Canvas for all the courses and stu-

dents are already used to it. Moreover, students would

not have to download a new application to complete

practice quizzes. Lastly, point results were important

to students. Students were analyzing their work on the

practice quizzes even though they were getting partic-

ipation credit just for completing the practice quizzes.

This could be because they wanted validation of their

knowledge, a sense of achievement and/or to help pre-

pare them for the exams.

Among the students, 44 had previously taken an-

other course that had the option of using MILAGE

LEARN+, and 29 used Canvas and 15 used MILAGE

LEARN+ in that course. However, 32 used Canvas

and 12 used MILAGE LEARN+ in this study. The

reduction in the number of students using MILAGE

LEARN+ can be attributed to their past experience,

which was probably not as good as that with Canvas,

a more established and well-integrated application.

Limitations. This study faced some limitations re-

lated to MILAGE LEARN+. During the time of our

study, the application was under an update which af-

fected the timely roll out of practice quizzes to stu-

dents impacting some students’ ability to complete

practice quizzes before an assignment or exam. Is-

sues such as incorrect quizzes or quizzes where stu-

dents could not see the questions posed challenges.

MILAGE LEARN+ doesn’t have an automatic

grading system for fill-in-the-blank questions. We

wanted to include these as an “expert” difficulty level,

but we couldn’t because students would have to grade

themselves, leading to potential dishonesty.

MILAGE LEARN+ is an external application that

students needed to download separately in compari-

son with Canvas, which was already integrated into

the school’s system. Some students were cautious of

this new application and either did not want to down-

load it or encountered difficulties in downloading the

app and creating an account.

MILAGE LEARN+ did not include timestamps

on when students submitted their practice quizzes.

This feature would have been beneficial to ob-

serve trends in how students approached the practice

quizzes, such as whether they completed the beginner

level first before moving on to the intermediate level.

The study design allowed students to choose their

own groups for practice quiz difficulty and feed-

back/platform type, resulting in uneven group sizes

and self-regulation bias. Although not ideal, it was

preferable compared to assigning students to differ-

ent groups. This method ensured that students’ exam

grades were not jeopardized, as the practice quizzes

were crucial for their study efforts. Assigning stu-

dents to groups could have been unethical, potentially

putting their grades at risk. However, this meant that

there was no control group as all of the students were

to participate in the practice quizzes to allow no one

group to have an unfair advantage.

6 CONCLUSION

The main goal of this study was to explore the impact

of using practice quizzes, varying their difficulty lev-

els, and using different feedback types on exam per-

formance and student learning in an advanced soft-

ware testing course. The results indicate that the ad-

dition of the practice quizzes improved student learn-

ing and scores on the midterm and final in comparison

with the semester prior without the practice quizzes.

Both brief and detailed feedback helped improve stu-

dent performance with the latter giving a more even

distribution of grades and consistent learning and the

former achieving higher exam performance but more

varied results across the group. This study can help

educators choose what they would prefer for their stu-

dents’ learning outcomes. Finally, varying difficulty

levels was shown to also increase student comprehen-

sion of difficult topics but only when used with com-

plex, thought-provoking questions. Specifically inter-

mediate level practice quizzes had the greatest im-

pact on student learning, granting high exam scores

to those students. While this study has limitations,

such as uneven sample sizes, it highlights the impor-

tance of well thought out practice quizzes to achieve

the goal of greater student learning.

In the future, we plan to do another study on vary-

ing the levels of difficulty with more than the two

levels (beginner true/false and intermediate multiple

choice quizzes) that are represented in the current

study. We will create question banks so that the stu-

dents can take the same quiz multiple times with dif-

ferent questions. We will also study the patterns of

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

214

usage, such as when the students take the quizzes

with respect to the exams, and how often they prac-

tice. This study would provide new insights into how

students use practice quizzes for their own learning.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported in part by the US Na-

tional Science Foundation under award number OAC

1931363. We also thank Mauro Figueiredo for allow-

ing and helping us to use MILAGE LEARN+.

REFERENCES

Almeida, L., Figueiredo, M., and Martinho, M. (2022).

Milage learn+: Perspective of teachers. In ED-

ULEARN22 Proceedings, 14th International Confer-

ence on Education and New Learning Technologies,

pages 6882–6887. IATED.

Burton, R. F. (2001). Quantifying the effects of chance in

multiple choice and true/false tests: Question selec-

tion and guessing of answers. Assessment & Evalua-

tion in Higher Education, 26(1):41–50.

Butler, D. L. and Winne, P. H. (1995). Feedback and self-

regulated learning: A theoretical synthesis. Review of

Educational Research, 65(3):245–281.

Case, J. and Kennedy, D. (2021). Using quizzes ef-

fectively: Understanding the effects of quiz timing

on student motivation and knowledge retention. In

2021 ASEE Virtual Annual Conference Content Ac-

cess, number 10.18260/1-2–37996, Virtual Confer-

ence. ASEE Conferences. https://peer.asee.org/37996.

Dorin, A., Moraes, M. C., and Figueiredo, M. (2024). Mi-

lage learn+: Motivation and grade benefits in com-

puter science university students. Frontiers in Educa-

tion.

Figueiredo, M., Fonseca, C., Ventura, P., Zacarias, M., and

Rodrigues, J. (2023). The milage learn+ app on higher

education. In HEAd’23: 9th International Conference

on Higher Education Advances. Accessed: 2024-10-

02.

Figueiredo, M., Martins, C., Ribeiro, C., and Rodrigues, J.

(2020). Milage learn+: A tool to promote autonomous

learning of students in higher education. In Monteiro,

J., Jo

˜

ao Silva, A., Mortal, A., An

´

ıbal, J., Moreira da

Silva, M., Oliveira, M., and Sousa, N., editors, IN-

CREaSE 2019, pages 354–363, Cham. Springer Inter-

national Publishing.

Little, J. L. and Bjork, E. L. (2015). Optimizing multiple-

choice tests as tools for learning. Memory & cogni-

tion, 43:14–26.

Lyle, K. B., Bego, C. R., Hopkins, R. F., Hieb, J. L., and

Ralston, P. A. S. (2020). How the amount and spac-

ing of retrieval practice affect the short- and long-term

retention of mathematics knowledge. In Educational

Psychology Review.

McDermott, K. B., Agarwal, P. K., D’Antonio, L., Roedi-

ger, H. L., and McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Both

multiple-choice and short-answer quizzes enhance

later exam performance in middle and high school

classes. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Ap-

plied, 20(1):3–21.

Moraes, M. C., Lionelle, A., Ghosh, S., and Folkestad, J. E.

(2024). Teach students to study using quizzes, study

behavior visualization, and reflection: A case study

in an introduction to programming course. In Pro-

ceedings of the 15th International Conference on Ed-

ucation Technology and Computers, ICETC ’23, page

409–415, New York, NY, USA. Association for Com-

puting Machinery.

Murphy, D. H., Little, J. L., and Bjork, E. L. (2023). The

value of using tests in education as tools for learn-

ing—not just for assessment. Educational Psychology

Review, 35(3):89.

Oudat, Q. and Othman, M. (2024). Embracing digital learn-

ing: Benefits and challenges of using canvas in edu-

cation. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice,

14(10):39–49.

Roediger, H. L. and Butler, A. C. (2011). The critical role

of retrieval practice in long-term retention. Trends in

Cognitive Sciences, 15(1):20–27.

Ross, B., Chase, A.-M., Robbie, D., Oats, G., and Absa-

lom, Y. (2018). Adaptive quizzes to increase motiva-

tion, engagement and learning outcomes in a first year

accounting unit. International Journal of Educational

Technology in Higher Education, 15.

R

¨

uth, M., Breuer, J., Zimmermann, D., and Kaspar, K.

(2021). The effects of different feedback types on

learning with mobile quiz apps. Frontiers in Psychol-

ogy, 12.

Sch

¨

utt, A., Huber, T., Nasir, J., Conati, C., and Andr

´

e, E.

(2024). Does difficulty even matter? investigating dif-

ficulty adjustment and practice behavior in an open-

ended learning task. In Proceedings of the 14th Learn-

ing Analytics and Knowledge Conference, LAK ’24,

page 253–262, New York, NY, USA. Association for

Computing Machinery.

Scully, D. (2017). Constructing multiple-choice items to

measure higher-order thinking. Practical Assessment,

Research & Evaluation, 22:4.

Shute, V. J. (2008). Focus on formative feedback. Review

of Educational Research, 78(1):153–189.

Thierbach, C., Hergesell, J., and Baur, N. (2020). Mixed

methods research. SAGE publications Ltd.

Uner, O., Tekin, E., and Roediger, H. L. (2021). True-false

tests enhance retention relative to rereading. Journal

of experimental psychology. Applied.

YeckehZaare, I., Aronoff, C., and Grot, G. (2022).

Retrieval-based teaching incentivizes spacing and im-

proves grades in computer science education. In Pro-

ceedings of the 53rd ACM Technical Symposium on

Computer Science Education - Volume 1, SIGCSE

2022, page 892–898, New York, NY, USA. Associ-

ation for Computing Machinery.

YeckehZaare, I., Resnick, P., and Ericson, B. (2019). A

spaced, interleaved retrieval practice tool that is mo-

tivating and effective. In Proceedings of the 2019

ACM Conference on International Computing Educa-

tion Research, ICER ’19, page 71–79, New York, NY,

USA. Association for Computing Machinery.

Evaluating the Effect of Practice Quizzes on Exam Performance in an Advanced Software Testing Course

215