Which Factors Influence the Success of Communities of Practices in

Large Agile Organizations, and How Are They Related?

Franziska Tobisch

a

, Johannes Schmidt

b

, Ahmet S¸ent

¨

urk and Florian Matthes

c

Technical University of Munich, School of Computation, Information and Technology,

Department of Computer Science, Garching, Germany

Keywords:

Barriers, Success Factors, Communities of Practice, Large-Scale Agile.

Abstract:

Agile software development methods are intended to allow quick reactions to frequent changes. The success

of these methods in small settings has motivated organizations to scale them. However, dependencies, col-

laboration, and alignment become challenging in this context. Communities of Practice (CoPs) can support

addressing the mentioned problems, but organizations have struggled with their implementation. Also, exist-

ing research lacks empirical studies on factors influencing CoPs’ success across organizations. Thus, we ran

an expert interview study investigating factors hindering and supporting the success of CoPs in scaled agile

settings and explored how they influence each other. Our findings highlight that establishing and cultivating

CoPs should be aligned with organizations’ and communities’ contexts. Key barriers are a lack of (attending)

members, limited time due to daily work, and difficulties in the CoP organization. Especially value for organi-

zation and members, a suitable organization of CoP internal activities, and regular adaption and improvement

foster success.

1 INTRODUCTION

Continuous changes in today’s business environment

require companies to respond fast and frequently to

stay ahead of their competitors (Van Oosterhout et al.,

2006), especially in software development (High-

smith, 2002). Since traditional development methods

cannot provide this level of agility (Highsmith, 2002),

the popularity of agile methods and frameworks like

Scrum, which are well-suited to this requirement,

grew strongly (Digital AI, 2023). Following the suc-

cess of agile methods in small-scale contexts, like

single-team projects, organizations have started to

scale their adoption (Digital AI, 2023; Dikert et al.,

2016), for instance, by applying them in multi-team

contexts and across the organization (Dingsøyr and

Moe, 2014). However, as agile methods were in-

tended for single teams, transforming organizations

towards applying agility at scale is complex (Dig-

ital AI, 2023; Dikert et al., 2016). Besides miss-

ing knowledge and experience regarding scaled ag-

ile approaches, the expanded scope increases the risk

of dependencies, knowledge silos, and misalignment

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0004-7250-4635

b

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-0863-700X

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6667-5452

in agile practices (Digital AI, 2023; Dikert et al.,

2016). At the same time, the coordination effort

grows (Digital AI, 2023; Dikert et al., 2016). Cross-

organizational collaboration, exchange (Digital AI,

2023; Dingsøyr and Moe, 2014), and alignment (Dik-

ert et al., 2016) become crucial for success. Com-

munities of Practice (CoPs), groups of people who

share an interest and exchange ideas, experiences,

and knowledge regularly (Wenger et al., 2002), are

mechanisms claimed to help companies achieve these

goals (Disciplined Agile, 2024; Kniberg and Ivarsson,

2012; LeSS, 2024; SAFe, 2023).

While existing research confirms CoPs’ potential

to support the adoption of agile methods at scale

(Detofeno et al., 2021; K

¨

ahk

¨

onen, 2004; Korbel,

2014; Paasivaara and Lassenius, 2014;

ˇ

Smite et al.,

2019a,b), it also shows that implementing them is

challenging. Multiple studies have investigated and

reported challenges, best practices, hindering, and

supporting factors for adopting CoPs in scaled agile

settings (e.g., Detofeno et al. (2021), Paasivaara and

Lassenius (2014),

ˇ

Smite et al. (2019a),

ˇ

Smite et al.

(2019b)). Still, these studies mainly focus on individ-

ual organizations. Hence, additional research is re-

quired to validate the findings’ applicability in other

organizational contexts and extend them. Thus, we

defined two research questions (RQs) for our study:

Tobisch, F., Schmidt, J., ¸Sentürk, A. and Matthes, F.

Which Factors Influence the Success of Communities of Practices in Large Agile Organizations, and How Are They Related?.

DOI: 10.5220/0013200000003929

In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2025) - Volume 2, pages 15-26

ISBN: 978-989-758-749-8; ISSN: 2184-4992

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

15

Which factors hinder and foster the success of CoPs

in scaled agile settings? How are these factors related

to each other?

To answer these RQs and fill the described re-

search gap, we carried out an interview study with 39

participants from 18 organizations to investigate fac-

tors influencing the success of CoPs in scaled agile

settings and how they are related. With our findings,

we aim (1) to provide insights into the factors hinder-

ing and fostering the success of CoPs in scaled ag-

ile settings, (2) to support CoP leads, initiators, mem-

bers, and organizations in the establishment and cul-

tivation of CoPs by identifying starting points for im-

provement or avoiding potential impediments, and (3)

to build a foundation for identifying future research

topics.

The paper is structured as follows: First, we pro-

vide a theoretical background on CoPs, their imple-

mentation in scaled agile contexts, and potential chal-

lenges and success factors. Then, we describe our re-

search design and present our findings. Finally, we

discuss the implications of our findings, explain limi-

tations, and propose future research directions.

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Communities of Practice (CoPs)

CoPs can be defined as groups of people sharing

a concern or specific problem or being enthusias-

tic about a subject, enhancing their understanding

and skills through regular interactions (Wenger et al.,

2002). A CoP is characterized by its members’

shared interest (Domain), their interactions (i.e., col-

laboration, support, knowledge exchange) (Commu-

nity), and the shared set of knowledge, experiences,

and approaches it creates (Practice) (Wenger et al.,

2002). Compared to other group structures, like

project teams, CoPs differ in at least one of the fol-

lowing aspects: purpose, members, boundaries, moti-

vation, and lifespan (Wenger et al., 2002). For a CoP,

the purpose is the creation, expansion, and exchange

of knowledge, and the development of individual ca-

pabilities. A CoP’s members are self-selected based

on their expertise or enthusiasm for a topic. A CoP

has fussy boundaries, and the motivation of its mem-

bers relies on their enthusiasm, dedication, and con-

nection to the community and its knowledge base. A

CoP develops over time and dissolves organically.

CoPs can vary in many aspects, including their

scope, size, level of organizational support, or how

institutionalized they are (Wenger et al., 2002; Jassbi

et al., 2015). CoPs can provide their members and the

organization with short- and long-term values (e.g.,

personal development, discovery of synergies across

units (Wenger et al., 2002), organizational efficiency

and speed (Fontaine and Millen, 2004)). Still, sus-

taining a community throughout its lifecycle is chal-

lenging, and factors like the distribution of commu-

nity members add complexity (Wenger et al., 2002).

To avoid pitfalls, Wenger et al. (2002) recommend re-

specting the following principles: “Design for evo-

lution,” “Open a dialogue between inside and out-

side perspectives,” “Invite different levels of partici-

pation,” “Develop both public and private community

spaces,” “Focus on value,” “Combine familiarity and

excitement,” and “Create a rhythm.”

2.2 CoPs in Scaled Agile Software

Development

CoPs can be a tool to support adopting agile meth-

ods at scale (K

¨

ahk

¨

onen, 2004; Paasivaara and Lasse-

nius, 2014;

ˇ

Smite et al., 2019a,b). The communities

allow experts, usually spread across various cross-

functional teams, to connect, interact, and collaborate

(Tobisch et al., 2024). CoPs can help foster continu-

ous learning and leverage different experiences and

expertise in an organization (Tobisch et al., 2024).

Also, CoPs can empower employees to actively in-

fluence the organization, align areas, teams, and roles

across the organization, and support the agile transfor-

mation through the distribution and creation of knowl-

edge about agile practices (Paasivaara and Lassenius,

2014;

ˇ

Smite et al., 2019a,b; Tobisch et al., 2024).

Organizations establish CoPs for various themes

beyond “agile”. In addition to CoPs focused on ag-

ile roles or agility itself, common themes include ar-

chitecture and software development (Tobisch et al.,

2024).

Several studies and reports on CoPs in scaled ag-

ile settings describe factors hindering and supporting

their successful establishment and cultivation.

ˇ

Smite et al. (2019a) investigated Spotify’s cultiva-

tion of CoPs and identified recurring challenges and

prerequisites for success. According to the authors,

defining the CoP’s purpose, finding time, achieving

engagement, and connecting CoP members across

sites are challenging. The found success factors in-

clude a clear purpose and direction, sponsorship, a

passionate leader, and dedicated time for CoP work.

ˇ

Smite et al. (2020) provide insights on barriers

to and enablers for engagement in Spotify’s CoPs.

According to the authors, a large CoP size, member

distribution, and lacking organizational support re-

duce engagement, while regular exchanges, cross-site

events, and virtual communication channels support

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

16

it.

Paasivaara and Lassenius (2014) investigated how

Ericsson adopted CoPs while transforming to lean

and agile methodologies. The authors identified eight

characteristics of successful CoPs: interesting topic,

passionate leader, a proper agenda, decision-making

authority, openness, transparency, suitable rhythm,

and cross-site participation.

Ojasalo et al. (2023) studied CoPs at a Finnish

company undergoing an agile transformation, high-

lighting challenges like a vague understanding of

CoPs’ nature, them being overlooked and -managed,

and low recognition and support. According to the au-

thors, engagement activities, value for members and

organization, and a defined working model can foster

success.

ˇ

Smite et al. (2019b) studied corporate-level com-

munities at Ericsson and identified factors that influ-

enced their success. According to the authors, for ex-

ample, limited decision-making authority, poor atten-

dance and activity, and lacking visibility of CoP work

are challenging. Strengthening factors include com-

munity members acting as ambassadors, member par-

ticipation and engagement, and transparency.

Detofeno et al. (2021) investigated a CoP for tech-

nical debt in a large agile project, reporting several

factors hindering and supporting its success. The

found challenges include aligning members’ issues

with organizational needs, a needed culture shift, time

constraints, and quantitatively evaluating results. The

found success factors include management support

and alignment, tool support, well-defined objectives,

and qualified CoP members.

Geffers (2024) studied the role of online CoPs in a

company undergoing an agile transformation. The au-

thor found that voluntary participation can strengthen

employees’ intrinsic motivation, while the company’s

merger led, for example, to cultural differences.

Korbel (2014) provides insights from establish-

ing CoPs at Digital Globe, including challenges like

lacking time commitment, failed expectation manage-

ment, low attendance, and no value perceived by par-

ticipants.

Kopf et al. (2018) share patterns for the suc-

cess of CoPs in agile IT environments to avoid

common pitfalls: securing management attention, a

suitable implementation plan, and encouraging self-

organization.

Finally, Monte et al. (2022) conducted a literature

review on CoPs in large-scale agile software develop-

ment, finding success factors like a suitable rhythm

and agenda, an interesting topic, management sup-

port, and an engaged CoP leader.

While these studies identify various partly recur-

ring, challenging, and supporting factors, a broad em-

pirical study across organizations does not exist yet.

3 RESEARCH DESIGN

Interview Study Design. The research design for

our study is based on qualitative data collection, as

implementing CoPs in large-scale agile environments

presents a practical challenge (Seaman, 1999). We

conducted semi-structured expert interviews (Fontana

and Frey, 2000; Myers and Newman, 2007; Seaman,

1999) following the guidelines of Myers and New-

man (2007) to ensure rigor. Within this study, we

combine exploratory with descriptive and explanatory

elements. The study participants include 39 experts

from 18 organizations (see Table 1 and 2). Thereby,

we used a mix of convenience and purposive sampling

(Kitchenham and Pfleeger, 2002). We reached out to

suitable candidates individually (e.g., by e-mail) and

distributed a call for participation through existing

contact networks. Still, we only interviewed experts

working in large-scale agile settings (Dingsøyr and

Moe, 2014) that have CoPs established and who are

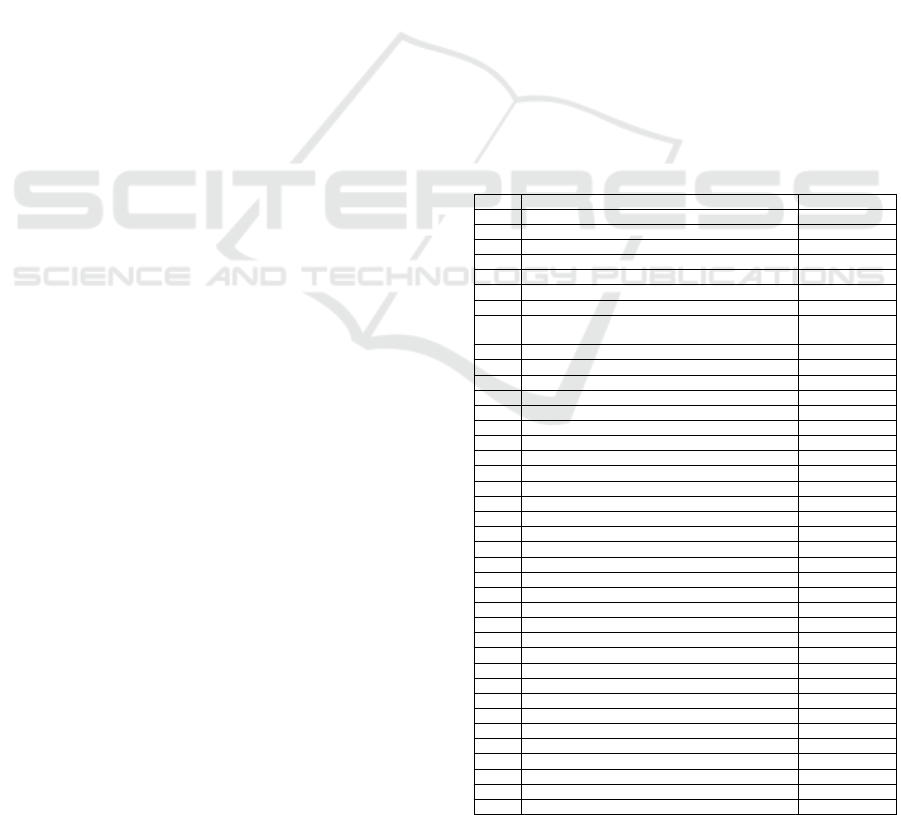

Table 1: Interview partners.

ID Job role — CoP role Org.

E1 Manager — Lead, Stakeholder SoftwareCo1

E2 Enterprise Architect — Member InsureCo1

E3 Agile Coach, Program Manager — Lead SoftwareCo2

E4 Manager — Lead ConsultCo1

E5 Software Architect — Member SoftwareCo2

E6 Consultant, Q&A Specialist — Member ConsultProj

E7 Manager, Agile Master, CoP Lead — Lead CarCo1

E8

Security & Infrastructure Expert,

Scrum Master — Lead, Member

SoftwareCo2

E9 Developer, Scrum Master — Member SoftwareCo2

E10 Agile Coach — Lead, Member CarCo2

E11 Business Analyst — Lead ConsultCo1

E12 Scrum Master — Lead SoftwareCo2

E13 Agile Coach, Manager — Member ElectroCo

E14 Agile Coach — Lead ElectroCo

E15 Agile Coach — Lead, Member FoodCo

E16 Scrum Master — Lead SoftwareCo2

E17

Agile Coach, Consultant, Pr. Owner — Lead

ConsultCo2

E18 Agile Coach, Scrum Master — Lead ConsultCo1

E19 Consultant — Lead ConsultCo3

E20 Developer, Agile Coach — Lead TeleCo1

E21 CoP Lead — Lead InsureCo1

E22 Software Architect — Member HealthCo

E23 Agile Coach, Enterprise Architect — Lead InsureCo1

E24 Enterprise Architect — Lead FashionCo

E25 Solution Architect — Member TransportCo

E26 Solution Architect — Lead, Member TransportCo

E27 Manager — Lead, Member RetailCo

E28 System Architect — Lead, Member TransportCo

E29 Enterprise Architect, Manager — Member TransportCo

E30 Project Manager — Lead RetailCo

E31 Manager — Stakeholder TeleCo2

E32 Product Owner — Lead TransportCo

E33 Organizational Developer — Stakeholder TeleCo2

E34 Enterprise Architect — Member TeleCo2

E35 Enterprise Architect — Lead, Member InsureCo2

E36 Agile Master — Member TeleCo2

E37 Organizational Developer — Lead, Member TeleCo2

E38 Disciplinary Leader — Member TeleCo2

E39 Agile Master — Lead TeleCo2

´

Which Factors Influence the Success of Communities of Practices in Large Agile Organizations, and How Are They Related?

17

a CoP lead, member, or stakeholder (e.g., a sponsor).

Also, we focused on different job roles and industries

to include multiple viewpoints (Myers and Newman,

2007). When we interviewed multiple experts from a

single company, we tried to involve people in differ-

ent roles, organizational areas, and CoPs.

Data Collection. We conducted the interviews in

two rounds: 23 interviews from February to May

2023 and 16 from November 2023 to January 2024.

Most interviews lasted 40–60 minutes. All interviews

in both rounds had a similar outline. However, we

incorporated some changes for the second round to

enhance the data collection through our previously

gained experience and focus on investigating barri-

ers and success factors. The interviews were divided

into questions about the interviewees, CoPs within

their organizational setting, potential support for CoP

adoptions (first round), and challenges and good prac-

tices (second round). Most questions were open, al-

lowing for detailed answers. We recorded and tran-

scribed all interviews except one. In addition, we in-

corporated data sources (e.g., documents, websites)

with information about certain CoPs shared by the ex-

perts for data triangulation.

Data Analysis. We performed the data coding and

analysis following the guidelines of Miles et al.

(2014) and Salda

˜

na (2021), using a two-cycle ap-

proach that combined deductive and inductive coding.

Inductive coding was the primary means to determine

the barriers and success factors. Additionally, we an-

alyzed the experts’ statements regarding potential re-

lationships between barriers and success factors. To

clarify uncertainties and fill in information gaps, we

reached out to the interviewees.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Barriers to the Success of CoPs

We identified 24 barriers to the success of CoPs in

scaled agile settings mentioned by at least three ex-

perts from three organizations (see Table 3).

(B1) Lack of (attending) CoP Members: A lack of

members or members not attending CoP meetings is

one of the most common barriers to the success of

CoPs in scaled agile environments. On the one hand,

many CoPs struggle to get people to become mem-

bers. For example, according to E23 “it’s incredi-

bly difficult and time intensive to try to get people on

board.” On the other hand, many CoPs suffer from

low attendance in regular exchanges. For example,

in the central Scrum Master CoP of SoftwareCo2 “in

some of these meetings, [there] are only 4 or 6 people.

But the invitation list is longer” (E8). Often, a lack of

(attending) members is caused by other barriers, like

time limitations (B2).

(B2) Lack of time due to daily work: Many CoPs

struggle with the limited time employees can dedicate

to the community and related activities (e.g., prepara-

tion tasks) due to the high amount and priority of their

daily work. Consequently, the capacity to initiate and

lead CoPs can be low (B14), and attending CoP meet-

ings difficult (B1). According to E24, low member

numbers at FashionCo are commonly caused by “tim-

ing issue. It’s finding the time to join these communi-

ties.” This barrier can originate from a lack of man-

agement support (B8). For example, at CarCo2, an

Agile CoP struggled because “there was not the nec-

essary backup for the participants from their own de-

partments. So, they just didn’t get enough time to in-

vest in the community” (E10).

(B3) Difficulties in organizing CoP(s): Another

common barrier is difficulties in the organization of

CoPs. On the one hand, these difficulties include

problems in the overall organization-wide approach

to CoPs, like a lack of structure in the community

landscape. On the other hand, difficulties occur in

individual CoPs, like “no discussion or no valuable

discussion” (E14) in meetings. A potential cause for

such problems is a large CoP size (B17), which can

complicate finding a meeting slot suiting most mem-

bers and organizing regular meetings effectively. E4,

for example, wonders: “Once a community reaches

a certain size, how can this be organized [so] [...]

you’re still producing results and don’t go into [..] a

lecture?”

(B4) Lack of (perceived) value: CoPs not being per-

ceived as valuable and needed from an organizational

point of view and by (potential) members can hin-

der their success. Management, for instance, often

does not recognize the long-term value of activities

like knowledge sharing or employee development that

happen outside of the day-to-day business. (Potential)

members often perceive the topics discussed in a CoP

as irrelevant to their daily work, do not feel a need

for networking, or do not see other benefits. Accord-

ing to E30, “the biggest challenge is [...] that the

participants [do not] see the added value in it.” As

a potential consequence, people are not interested in

participating in CoPs (B6).

(B5) Lack of engagement: Another common bar-

rier is low engagement within CoPs. Often, members

hesitate to propose topics for meetings and prefer to

listen instead of actively participating in discussions

and contributing. This deficit can lead to CoPs be-

ing “one-way communication channels” (E22). E24

describes that for the CoPs at FashionCo, the biggest

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

18

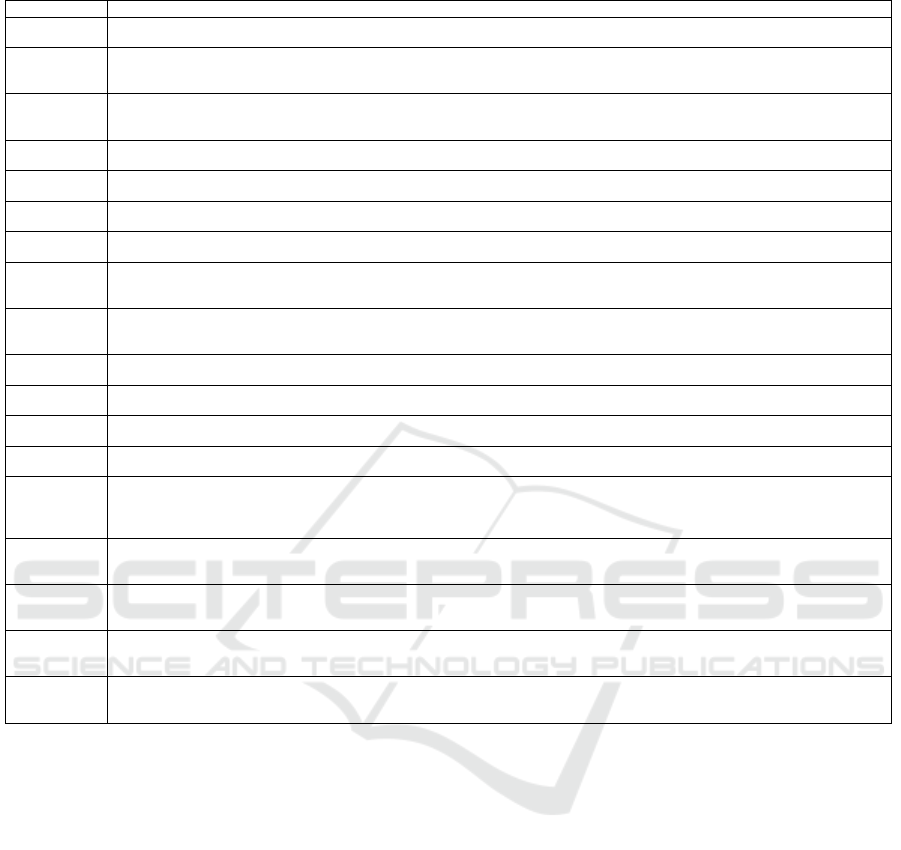

Table 2: Expert development organizations.

Org.

Details (e.g., scaling agile framework)

SoftwareCo1

The company has 20-30 employees working in two development teams. The applied framework is custom. E1 works with both teams.

Two CoPs exist within the company: a software quality CoP and a data science and AI CoP.

SoftwareCo2

The company has over 30.000 developers across diverse areas. E9, E12, and E16 focus on solutions in the retail industry, E5 and E8 in

the manufacturing sector, and E3 on technology innovation delivery. The framework varies by area and is often customized. Many CoPs

exist, including a Quality CoP in retail, a UI/UX CoP in manufacturing, and a company-wide Scrum Master CoP led by E3.

InsureCo1

E2, E21, and E23 are part of the IT division of InsureCo1’s German branch, which employs 2000 people and comprises 20 tribes, each

consisting of 2 to 25 teams. The framework used is customized and builds on Spotify, LeSS, and SAFe. Multiple CoPs exist within the

organization. Examples are CoPs for architecture, Agile Masters, and Product Owners .

ConsultCo1

E4, E4, E11, and E18 are involved in one customer project, which comprises eight programs, a total of 35 feature teams, and 450

employees. A customized framework is utilized for this project and various CoPs exist, for example, for architecture and agility.

ConsultProj

E6 is supporting a project as a consultant. This project comprises seven Scrum teams of a total of 100 employees and applies a custom

framework based on LeSS. Several CoPs exist within the project, including a Scrum Master CoP and a CoP for testing.

CarCo1

E7 works in a division of CarCo1’s enterprise IT with approximately 600 employees, divided into multiple domains. The applied

framework is area-specific. E7’s department has established multiple CoPs, such as a CoP for Agile Masters.

CarCo2

E10 works in the enterprise IT unit of the company with circa 900 employees in around 120–140 teams. The used framework contains

SAFe elements. Various CoPs exist within the company, for instance, a CoP for collaboration and collaboration tools.

ElectroCo

The IT division of the company has over 800 employees distributed into 100 product teams, which are divided into domains on different

levels. E13 and E14 work with multiple domains. The implemented framework is customized and inspired by Spotify. The IT division

has several CoPs established, for example, for engineering, architecture, and Agile Coaches.

FoodCo

The IT unit of the company has over 2000 employees, working in 150-200 teams, which are grouped into domains. E15 operates at the

level of the entire IT unit. The implemented framework builds on LeSS. The IT unit has multiple CoPs with different scopes established,

such as CoPs for software craftsmanship, security, and Kanban.

ConsultCo2

The company is a small consulting firm acquired by a larger one, employing several hundred people. E17 belongs to a team with circa 50

consultants. The scaling framework used is client-specific. Different CoPs exist, for instance, for transformation and change, and agility.

ConsultCo3

E19 is a self-employed consultant with experience in establishing CoPs in different contexts, leading a cross-organizational CoP on

agility.

TeleCo1

E20 worked in a department with 100 developers grouped into eight teams. The implemented framework is custom, integrating elements

from Scrum-of-Scrums and LeSS. In the department, multiple CoPs existed, for example, for agility and security.

HealthCo

In the company’s IT unit, over 1000 individuals are engaged in various projects. E22’s project consists of 30 teams of, in total, around

250 developers. The applied framework uses parts of SAFe. CoPs exist in and across projects, for example, for requirement quality.

FashionCo

The company’s IT division is divided into multiple domains with a total of around 400–500 employees. E24 works at the IT division

level, not in a specific domain. Only certain parts of the IT operate in an agile manner, utilizing a customized framework influenced by

SAFe. The IT division has several CoPs, particularly across all domains, for example, for architecture, Front-end Engineers, and Scrum

Masters.

TransportCo

The IT unit of the company employs over 1300 people. The applied framework is SAFe. E25, E26, and E28 are part of different large

solutions and ARTs. E29 and E32 work is independent of any ART or large solution. Many CoPs on various levels exist, for instance,

for architecture and software development. A supporting IT sub-company also has several CoPs established.

RetailCo

The IT division of the company employs more than 2500 people and is structured into various departments. The applied framework is

custom. E27 is part of a department with around 230 people in 30 product teams. E30 works on the IT division level. Additionally, 20

streams for cross-department projects exist. Multiple CoPs within and across departments exist, for example, digitalization.

TeleCo2

The company’s IT unit comprises around 1000 people, with 30 teams distributed over 10–15 tribes. E31, E33, E34, and E36–39 work on

the IT unit level or with multiple teams. The framework utilized is customized, with names inspired by Spotify. Multiple CoPs exist, for

example, for business analysts, and leadership and management roles. E37 coordinates a CoP spanning multiple organizations.

InsureCo2

The agile section of InsureCo2’s IT has around 220 employees distributed across four value streams, with each 4–8 teams. The imple-

mented framework is custom. Moreover, several IT projects are carried out. E35 works at the overarching IT division level. Several CoPs

exist at this level and between value streams and projects, for instance, CoPs for business analysis, security, and Architects.

problem “at first [...] was to move from a consumer

mindset to a contributor mindset. Because it’s a dif-

ferent way of working, and that took just some time.”

Low engagement can have various causes, for exam-

ple, a format not allowing for contributions (B3).

(B6) Low motivation of (potential) CoP members:

Low motivation and interest of individuals to partici-

pate in a CoP is a common impediment. As a result,

people refrain from joining CoPs as members and do

not attend CoP meetings (B1) or engage (B5). Often,

people are not interested in being part of a CoP be-

cause they do not see its value (B4). According to E4,

“if they don’t see a clear benefit for their day-to-day

job, then it’s hard to get people motivated to work in

the CoP.”

(B7) Hindering organizational culture and Mind-

set: In many companies, the organizational culture

and the overall and individual mindset impede CoPs’

success. Common culture problems are traditional

ways of thinking and working, resistance towards ag-

ile principles, and missing awareness that activities

like knowledge sharing can support organizational de-

velopment. A common consequence is that manage-

ment is less willing to support CoPs (B8). E23 de-

scribes this problem as follows: “We also got the

company culture difficulties that you need to bridge.

So it’s quite easy to start with the idea, but you need

the buy-in from management to actually get the time.”

Also, individuals often lack openness and fear sharing

experiences (B5) or change.

(B8) Lack of management support: In many cases,

lacking management support hinders CoPs from be-

ing successful. Difficulties in convincing manage-

ment to support CoPs, lack of budget, or managers

not allowing employees to spend enough time in CoPs

(B2) can be challenging. According to E36, for the

Agile Master CoP at TeleCo2, “time, budget, that are

[...] the biggest challenges. Yes, you can get quite far

without a budget, but it would be nice, of course, since

we are spread all over [the country] if we at least had

the budget to make an off-site once a year.”

(B9) Difficulties in starting CoP(s): Another bar-

Which Factors Influence the Success of Communities of Practices in Large Agile Organizations, and How Are They Related?

19

rier to CoP success is problems during their initiation

and formation, like difficulties in identifying potential

suitable members and advertising it. As a potential

consequence, CoPs struggle to gain members (B1),

and the effort for initiators increases (B11). E15 ex-

plains: “To make CoPs work, you have to invest time

[...] and [...] a lot of patience [...] to make this or-

ganization aspect click and get people to work in the

way of CoPs.”

(B10) Hindering organizational setting: The or-

ganizational setting can negatively affect CoPs’ suc-

cess. Examples are complicated company-internal

processes and structures, a large company size, or

strict policies limiting the tools that can be used

(B12). Moreover, if an organization like a consult-

ing company works for clients, booking time for CoP

work is complicated (B3). E11 elaborates on this is-

sue at ConsultCo2: “This exchange costs time. [..]

and that it’s not really bookable to the customer,

right? [...] at the end, it just improves your way of

working. But it’s not directly bookable.”

(B11-24) A high amount of effort required for initia-

tors and leads to establish and maintain CoPs (B11)

can have negative effects if the leads and initiators are

not able or willing to spend this time and effort. In-

sufficient tool support, like missing features or unreli-

ability (B12), can complicate organizing CoPs (B3).

Alternative formats, like similar CoPs or meetings

(B13), can make CoPs obsolete (B4). Not having

skilled and motivated CoP initiators and leads who

build the CoP up, organize meetings, and motivate

(potential) members (B14) counteracts success. High

time and effort required to participate in CoPs (e.g.,

for meeting preparation) (B15) can stop people from

joining (B1). Heterogeneous CoP members (B16) can

complicate the organization (B3), for example, due to

different interests and ways of working. Despite the

relevance of members, also a large CoP size (B17)

can complicate, for instance, communication, coordi-

nation, and finding a meeting slot (B3). Difficulties

in assessing the success and impact of CoPs (B18)

can make it hard to prove their added value (B4). A

missing correct understanding of the CoP concept and

its potential benefits (B19) can negatively affect the

value perceived (B4). No shared understanding of a

CoP’s topic and purpose between members (B20) can

decrease engagement (B5). The geographical distri-

bution of members (e.g., across time zones) (B21)

makes it challenging to find suitable CoP meeting

slots (B3). A virtual setting for CoP exchanges (B22)

often impedes collaboration and establishing personal

connections between members, which can negatively

affect engagement (B5). Organizational changes, like

intense personnel fluctuations (B23), can lead to a de-

crease in members (B1). Finally, steering (by man-

agement) (B24) can harm engagement (B5), for ex-

ample, since people fear being controlled.

4.2 Factors Fostering the Success of

CoPs

We identified 24 factors fostering the success of CoPs

in scaled agile settings that at least three experts from

three organizations mentioned (see Table 4).

(SF1) (Perceived) value for the organization and

CoP members: The value of CoPs perceived by

members and the organization is the most commonly

mentioned success factor. For (potential) members,

value is often connected to the CoP topic’s relevance

for daily work and the option to collaboratively ad-

dress a need or a shared problem. Other aspects

perceived as valuable by individuals can be having

a “safe haven”, personal development through learn-

ing, or appreciation of the CoP engagement by man-

agers and colleagues. According to E11, CoP mem-

bers must “take value out of the meeting. [...] have

the feeling [...] that they learned something, or at

least that they had fun talking to some other people.”

Value for organizations is, for example, connected to

enhanced efficiency through collaboration and knowl-

edge sharing and the development of employees. Of-

ten, management is more prone to support when it

sees a CoP’s value (B8, SF4).

(SF2) Suitable organization of CoP internal activ-

ities: A common influence factor for CoP success is

the organization of its exchange and activities. This

organization can include having an agenda for reg-

ular meetings, embracing consistency, adopting ag-

ile practices like retrospectives, allowing topic con-

tributions by members, and having a facilitator for

exchanges. Depending on the context, suitable top-

ics and an appropriate CoP meeting location (i.e., vir-

tual, hybrid, or in-person) and format (e.g., work-

shops, presentations, discussions) should be chosen.

For example, according to E7, for the Agile Master

CoP at CarCo1 “it’s [...] very important that in each

of those community meetings, there’s not only one to

many people presentation, but we always have inter-

active parts.”

(SF3) Regular adaption and improvement: Adapt-

ing and improving a CoP regularly can influence its

success. Changes can be related to the topics dis-

cussed in the CoP, its structure (e.g., splitting or merg-

ing communities), and meeting format, and should al-

ways be situation- and context-dependent. Also, if not

needed, closing a CoP can make sense. For example,

E10 claims that “if you also realize, okay, the commu-

nity has run into a sort of lockdown or dead end road,

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

20

you also have to have the guts to say, okay, let’s stop

it in the end.” Meaningful changes can ensure that

the CoP remains valuable (B4, SF1) and can be facili-

tated through feedback by members and stakeholders

(SF8). According to E13, “changes come with the

evolution of CoPs and are needed since changes [...]

are part of agility.”

(SF4) Management support: Support by manage-

ment can play a vital role in CoPs’ success. This sup-

port can be in the form of budget and funding (e.g., for

events), resources like meeting rooms, advertising of

CoPs, or allowing employees to spend enough time in

them. Primarily, the latter can ensure that CoP mem-

bers, initiators, and leads have time for CoPs (B2,

SF16). According to E6, “[CoPs] should be backed

by [...] leadership that these are established, exist and

have the time to meet.” Transparency and involving

management (SF17) can foster its support.

(SF5) Suitable CoP set-up and governance: An-

other factor contributing to CoPs’ success is a suit-

able set-up and governance. This set-up should bal-

ance governance and self-management, have flat hier-

archies, and, depending on the context, enforce vol-

untary or mandatory participation. A CoP working

agreement between members can help to align them,

for instance, on common values (SF18). CoPs with

a certain degree of decision-making power and influ-

ence allow members to have an impact on the orga-

nization, boosting engagement (B5, SF12). E22 ex-

plains that “if you want to influence [...] the discus-

sion, [...] you have to be part of the discussion, and if

you have good arguments [...] you can influence how

something is done in the organization.”

(SF6) Motivation of (potential) CoP members:

Motivation and interest of (potential) members to par-

ticipate, learn, share, and be involved in a CoP is a

key building block to its success. For example, mo-

tivated members tend to attend (B1, SF21) and con-

tribute (B5, SF12). If people perceive a CoP as valu-

able (SF1), it can motivate them. According to E2,

“if [members] realize these benefits, they’re really in-

terested in further enhancing the community and im-

proving it.”

(SF7) Engagement and promotion activities: Ac-

tivities that promote and foster engagement can con-

tribute to a CoP’s success. These activities can be

incentives to join, like drinks and snacks or recog-

nition within the organization, an effective promo-

tion strategy (e.g., announcements in company-wide

meetings), proof of the potential of CoPs, and person-

ally reaching out to (potential) members. According

to E24, “sometimes it’s really a good idea to address

a person who’s mainly silent personally, [...], what do

you think? [...] Could you elaborate any further?”

Such measures can motivate (potential) members to

participate and engage (B6, SF6).

(SF8) Assessment of impact and success: Investi-

gating and reflecting on the impact and success of

a CoP can help ensure that it is perceived as valu-

able (B4, SF1) and allows for regular improvements

(SF3). This review can be done through feedback

from CoP members and stakeholders, regular retro-

spectives, surveys, and metrics. For example, E4 rec-

ommends: “Get feedback on a regular level. Are the

things which we are focusing on bringing value for

the people involved in the CoP? Is there anything that

we would change?”

(SF9) Availability of skilled and passionate CoP

initiators and leads: Motivated CoP initiators and

leads with the right skills are crucial for CoP suc-

cess. These persons should drive the CoP set-up and

organization, manage stakeholders, provide structure,

and motivate members. According to E28, “you need

key players who drive this and who set it up first and

who also feel responsible, for a whole first time, so

that it doesn’t fall asleep.” These individuals should

make a CoP work without prescribing topics or rules

and ensure activities and topics discussed align with

CoP goals. Initiators and leads should be passionate,

committed, open-minded, and ideally good facilita-

tors. Support for leads (e.g., coaching or CoPs for

leads) (SF20) can enhance their skills and knowledge.

(SF10) Supporting organizational culture: An or-

ganizational culture and a mindset of individuals valu-

ing and open towards agile practices, learning, sup-

porting, and sharing experiences can foster CoPs. A

supporting organizational culture can make it easier

to get management support (B8, SF4), and individu-

als with the right mindset are more motivated to join a

community (B6, SF6). For example, E9 explains: “In

our organization, the agile culture is quite good [...]

people understand that if you are [..] taking part in

such communities, you will benefit.”

(SF11-24). A suitable establishment approach, in-

cluding the selection of an appropriate topic, format,

target group, and communication strategy (SF11),

builds the foundation for a CoP’s success. Depend-

ing on the context, the initiation should be top-down

or bottom-up. Also, engagement of CoP members,

like contributions and good discussions (SF12), is es-

sential. Appropriate tool support, for instance, for

virtual meetings and workshops (SF13), facilitates

meeting and engaging (B1, B5, SF12, SF21). A

well-organized and accessible documentation of rele-

vant information like CoP meeting summaries or out-

comes (SF14) is important. Limited steering of CoPs

(by management), for example, regarding topics dis-

cussed (SF15), can have a positive impact on mem-

Which Factors Influence the Success of Communities of Practices in Large Agile Organizations, and How Are They Related?

21

bers’ motivation (B6, SF6). The time CoP leads and

members have for CoP meetings and tasks (SF16)

is crucial and depends highly on the degree of man-

agement support (B8, SF4). Transparency and stake-

holder engagement, like getting stakeholder feedback,

making results transparent, and involving manage-

ment (SF17), can increase the chances of getting sup-

port (B8, SF4). Trust within the CoP and good re-

lationships between members (SF18) can foster their

engagement (B5, SF12). Support for establishing

and cultivating CoPs, for example, help from Agile

Coaches or coaching for CoP leads (SF20), can foster

success. People with a correct understanding of CoPs

and their potential benefits (SF19) are more likely to

understand their value (B4, SF1). Naturally, mem-

bers who attend CoP meetings (SF21) are a central

element of a CoP. Defining a clear common goal and

strategy for a CoP (SF22) can foster a shared un-

derstanding of its topic and purpose among members

(SF23), which, in turn, can help perceive its value

(B4, SF1). Limiting the effort required for a CoP

membership, for instance, through facilitated meet-

ings (SF24), can ease convincing people to participate

(B1, SF21).

4.3 Relationships Between Barriers and

Success Factors

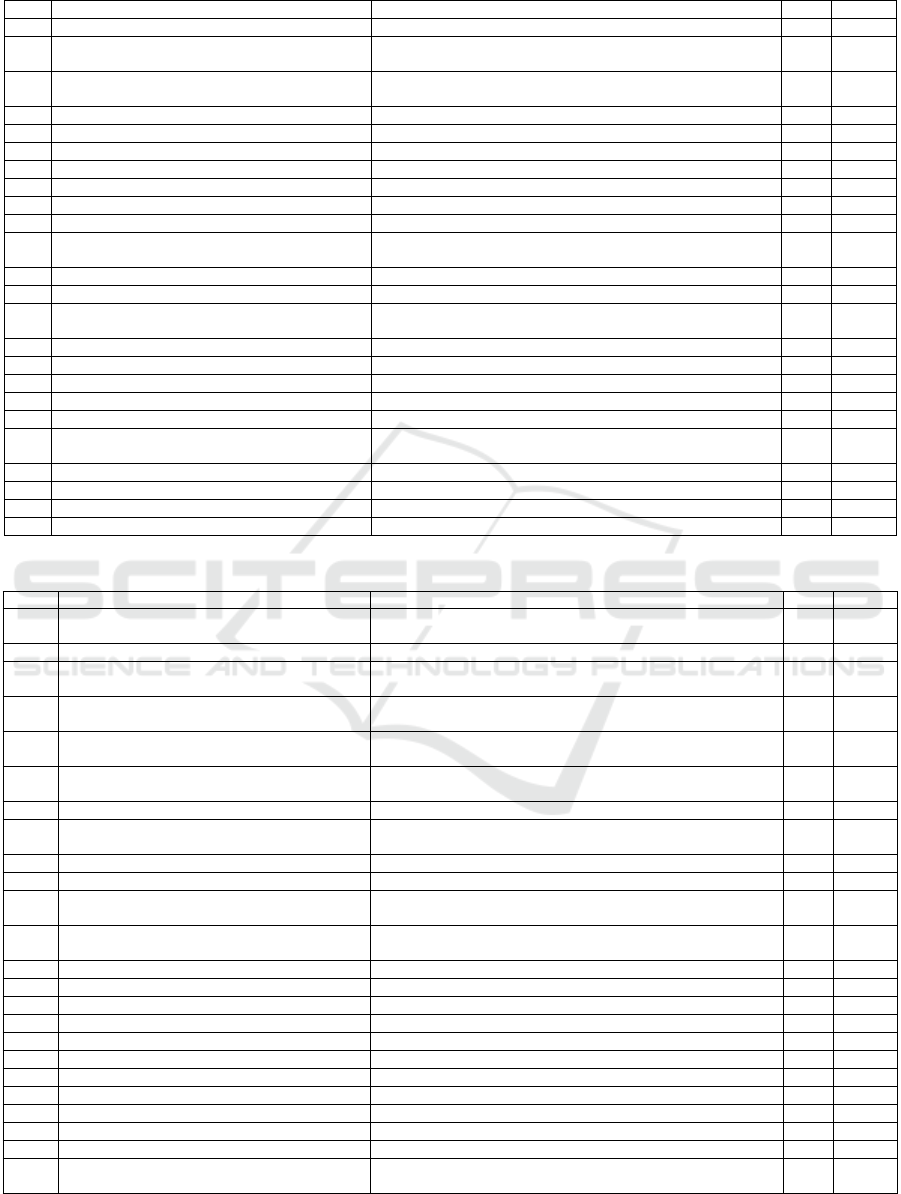

The barriers and success factors we identified are con-

nected: (1) barriers can cause other barriers, (2) suc-

cess factors can mitigate barriers, (3) success fac-

tors can reinforce each other, and (4) some barriers

and success factors are counterparts. To provide a

comprehensive overview of those relationships, we

mapped the barriers and success factors to variables

that influence the success of CoPs in scaled agile set-

tings and illustrated how they influence each other

(see Table 5). Several identified variables (V1–8), like

the geographical distribution of members (V3), only

have effects on others. Some variables (V15, V17,

V18, V24, V27), like skilled and passionate CoP ini-

tiators and leads (V18), influence a high number of

factors. The engagement of CoP members (V13) is

the only variable solely affected by others.

5 DISCUSSION

5.1 Key Findings

To answer our first RQ “Which factors hinder and fos-

ter the success of CoPs in scaled agile settings?”, we

identified 24 barriers and 24 success factors.

The most common barriers we found are a lack

of (attending) CoP members, limited time to partici-

pate in CoPs due to daily work, and difficulties orga-

nizing CoPs (B1–3). Similarly, Wenger et al. (2002)

and numerous studies on CoPs in scaled agile set-

tings have reported these barriers (Detofeno et al.,

2021; Korbel, 2014; Monte et al., 2022; Ojasalo et al.,

2023; Paasivaara and Lassenius, 2014;

ˇ

Smite et al.,

2019a,b, 2020). While also many other barriers we

found are mentioned in related work (see Section 2.2),

some barriers (B12, B13), like insufficient tool sup-

port (B13), to the best of our knowledge, have not

been reported yet. The diverse range of barriers we

identified underlines the complexity of implementing

CoPs in scaled agile settings.

The most common success factors we identified

are (perceived) value for the organization and mem-

bers, a suitable organization of CoP internal activ-

ities, and regular adaption and improvement (SF1–

3). These factors were also reported by Wenger

et al. (2002) and, for the most part, by related stud-

ies (Detofeno et al., 2021; Kopf et al., 2018; Korbel,

2014; Monte et al., 2022; Ojasalo et al., 2023; Paa-

sivaara and Lassenius, 2014;

ˇ

Smite et al., 2019a,b,

2020). However, despite continuous improvement be-

ing a key aspect of the agile manifesto (Beck et al.,

2001), only Wenger et al. (2002) emphasize its rele-

vance for CoP adaptions. Other authors only mention

certain aspects of this success factor, like closing a

CoP if not needed anymore (Kopf et al., 2018; Paasi-

vaara and Lassenius, 2014). Most other success fac-

tors we found are also reported in related work (see

Section 2.2). Still, we identified that a limited time

and effort required for members to participate in a

CoP (SF24) can be beneficial, which, to the best of

our knowledge, has not been explicitly highlighted by

other studies.

To answer our second RQ “How are the factors

influencing CoPs’ success related to each other?”,

we transformed the found barriers and success factors

into variables and illustrated how they impact each

other. The factors with the highest impact are CoP

governance (V27), organization of activities (V24),

skilled leads, and initiators (V18). While no other

related study focused on these relationships, several

highlight some links (e.g., Detofeno et al. (2021); Ko-

rbel (2014)), covering some connections we found

(e.g., perceived value (V12) can foster engagement

(V13)).

Our findings show that certain variables, i.e., (at-

tending) members (V9) and their homogeneity (V20),

can have positive and negative effects. While no CoP

would work without members, a large CoP size can

complicate its organization (e.g., finding common in-

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

22

Table 3: Barriers to the successful implementation of CoPs in scaled agile settings.

ID Barriers Experts # E. # Org.

B1 Lack of (attending) CoP members E1, E3, E4, E6–26, E28–31, E33, E35–37, E39

33 18

B2 Lack of time due to daily work

E1, E3, E4, E6, E10, E11, E14, E15, E17–21, E23-27, E29–37,

E39

28 16

B3 Difficulties in organizing CoP successfully

E1, E2, E4–7, E9, E11, E12, E14–17, E21–25, E26–30, E32,

E34, E36, E37

27 14

B4 Lack of (perceived) value E1–4, E6–8, E10, E11, E15, E21–26, E28–31, E33–35, E37–39

26 14

B5 Lack of engagement E2–6, E11, E12, E14, E16–19, E21–24, E26, E30, E32, E33, E35

21 13

B6 Low motivation of (potential) CoP members E2, E4, E7, E10–13, E18–23, E25, E29, E30, E37

17 12

B7 Hindering organizational culture and mindset E1, E7, E8, E10, E13, E15, E22–29, E31, E36

16 12

B8 Lack of management support E1, E3, E8, E10, E15, E18, E23, E24, E29, E32, E35, E36

12 10

B9 Difficulties in starting CoP(s) E4, E9, E11, E23, E25, E26, E28, E29, E34, E37

10 5

B10 Hindering organizational setting E4, E6, E7, E10, E11, E17, E26, E29, E30

9 8

B11

High time and effort required for CoP initia-

tors/leads

E4, E11, E15, E23, E24, E26, E27, E29, E32

6 6

B12 Insufficient tool support E6, E10, E14, E15, E17, E22, E23, E25

8 8

B13 Alternative formats E3, E6, E10, E13, E23, E26, E28, E32

8 6

B14

Lack of skilled and passionate CoP initia-

tors/leads

E14, E25, E28, E29, E31, E33–35

8 4

B15 High time and effort required to participate in CoP E7, E11, E19, E20, E29–31

7 6

B16 Heterogeneity of CoP members E2, E11, E15, E30, E33, E37, E38

7 6

B17 Large size of CoP E4, E21, E23, E25, E28, E34

6 4

B18 Difficulties in assessing success and impact E4, E7, E18, E23, E25, E28

6 4

B19 Lack of understanding of CoP concept E6, E11, E17, E25, E29

5 4

B20

No shared understanding of CoP topic and pur-

pose

E2, E7, E13, E21, E37

5 4

B21 Geographical distribution of members E11, E12, E14, E16

4 3

B22 Virtual setting E3, E11, E16, E30

4 3

B23 Organizational changes E5, E8, E24, E27

4 3

B24 Steering (by management) E19, E23, E35

3 3

Table 4: Success factors for the implementation of CoPs in scaled agile settings.

ID Success factors Experts # E. # Org.

SF1 (Perceived) value for organization and CoP

members

E1–4, E6, E7, E9-19, E21–28, E30-33, E35-39

34 17

SF2 Suitable organization of CoP internal activities E2, E3, E6–8, E10–18, E20–26, E28–39

33 16

SF3 Regular adaption and improvement

E2, E4, E6–8, E10, E12–19, E21–26, E28, E30, E31, E34, E37,

E39

26 15

SF4 Management support

E2, E4–6, E8, E10–12, E15, E16, E18–20, E23–25, E29, E30,

E32, E34, E36, E37

23 13

SF5 Suitable CoP set-up and governance

E2, E3, E6, E7, E11–16, E19–23, E25, E26, E28–30, E33, E34,

E37

23 13

SF6 Motivation of (potential) CoP members

E2, E6, E8, E11, E13, E14, E16, E18, E19, E21–26, E28, E29,

E32, E35–37, E39

22 11

SF7 Engagement and promotion activities E1, E2, E4–7, E13, E14, E17–22, E24, E25, E27–30, E37

21 15

SF8 Assessment of impact and success

E1–4, E7, E10, E12–16, E18, E23, E24, E26, E28, E30, E34,

E37, E39

20 12

SF9 Skilled and passionate CoP initiators/leads E2, E3, E7, E15, E16, E19, E20, E23–29, E32, E33, E35–37, E39

20 11

SF10 Supporting organizational culture E2, E3, E6–12, E16, E22–25, E29, E30, E36, E38, E39

19 11

SF11 Suitable establishment approach

E2, E3, E5, E9, E11, E12, E14–17, E21, E24, E26, E28, E29,

E33–35, E37

19 10

SF12 Engagement of CoP members

E2, E3, E5, E10, E12, E16, E18, E22–24, E26, E29, E30, E32,

E37

15 9

SF13 Appropriate tool support E2, E3, E6, E8, E10, E14, E15, E17, E21, E22, E24, E25, E39

13 12

SF14 Sustainable and efficient documentation E1, E2, E8, E14, E15, E18, E20, E22, E24, E26, E28, E34, E39

13 11

SF15 Limited steering (by management) E7, E11–15, E19, E23, E25, E29, E33, E34, E37

13 9

SF16 Time of members and leads for CoP E6, E8, E11, E12, E15, E18–20, E23, E29, E36

11 9

SF17 Transparency and stakeholder engagement E2–4, E7, E8, E15, E18, E24, E26, E29, E30

11 8

SF18 CoP cohesion E6, E11, E14, E16, E19, E30, E34, E36–39

11 7

SF19 Understanding of CoP concept E6, E11, E17, E25, E28, E29, E31

7 5

SF20 Support for set-up and organization E2, E6, E7, E14, E29, E38

6 6

SF21 (Attending) CoP members E6, E23, E25, E26, E29, E37

6 4

SF22 Clear common goal and strategy E13, E24, E26, E28, E30

5 4

SF23 Shared understanding of CoP topic and purpose E24, E26, E28, E35

4 3

SF24

Limited time and effort required for CoP mem-

bers

E15, E31, E35

3 3

Which Factors Influence the Success of Communities of Practices in Large Agile Organizations, and How Are They Related?

23

terests). Heterogeneous members can cause similar

problems but also enrich discussions and exchanges.

Several studies report similar issues caused by a large

CoP size or heterogeneous members (

ˇ

Smite et al.,

2019b, 2020; Wenger et al., 2002).

Our study’s results highlight the relevance of

adapting CoP implementation in scaled agile settings

to each organization and specific community con-

text. The difficulties in organizing CoPs (B3) that

we found vary between communities and organiza-

tions, and how a suitable CoP organization, estab-

lishment, governance, and adaption (SF2, SF3, SF5,

SF11) should look can differ. Moreover, that some

barriers, like a lack of skilled, passionate CoP initia-

tors and leads (B14), were mentioned by many ex-

perts, but, in comparison, in a few organizations high-

lights that some problems are only prevalent in cer-

tain contexts. Likewise, the organizational difficul-

ties different studies report are manifold (e.g., manag-

ing diverse CoP members (

ˇ

Smite et al., 2019b, 2020;

Wenger et al., 2002) vs. over-commitment (Korbel,

2014)) and different studies provide different recom-

mendations (e.g., self-organization (Kopf et al., 2018)

vs. management alignment (Detofeno et al., 2021)).

Also, some barriers, success factors, and the respec-

tive variables (e.g. supporting organizational culture

(V7)) are even determined by an organization’s or

CoP’s context and are only partly controllable. Still,

CoP leads, initiators, or organizations can control

other variables (V6, V8, V15, V17, V21, V23–25,

V27–31), like CoP internal activities (V24).

Our study has theoretical and practical implica-

tions. We confirmed prior findings and extended them

with novel insights across organizations. The iden-

tified variables impacting CoP success in scaled ag-

ile settings allow identifying future research topics

(e.g., approaches to assess the impact and success of

CoPs). Moreover, our findings aid practitioners in un-

derstanding the various factors influencing CoP suc-

cess, help companies to support CoPs by identifying

actionable factors, and guide CoP leads in finding

starting points for improvement, for example, vari-

ables that affect many others or that they can actively

influence.

5.2 Limitations

We assessed our study’s validity and identified poten-

tial threats (Runeson and H

¨

ost, 2009). To increase

external validity, we conducted more than 30 inter-

views with experts who differ in roles and company

backgrounds. To improve the reliability of our study,

we adhered to guidelines during the data collection

and analysis. Also, we clarified uncertainties during

the data analysis by contacting the interviewees. We

explained vital concepts and resolved potential am-

biguities at each interview’s start to foster construct

validity. To increase internal validity, we kept a sim-

ilar interview outline to collect data and focused on

patterns across organizations and CoPs. Still, the in-

ternal validity may be impacted by the high interview

participation of CoP leads, potentially overemphasiz-

ing lead perspectives. Also, the variation in intervie-

wees per organization could introduce bias. To en-

sure representativeness, we included only barriers and

success factors mentioned by experts of at least three

organizations and provided context on each organiza-

tional setting. We also indicated the number of orga-

nizations in which each barrier and success factor was

identified.

6 CONCLUSION

In this paper, we presented the results of an interview

study involving 39 experts from 18 organizations, ex-

ploring factors that influence the success of CoPs in

large-scale agile development. The most common

barriers are a lack of (attending) members, limited

time for CoP activities, and difficulties organizing

CoPs successfully. Key success factors identified are

the (perceived) value for organizations and CoP mem-

bers, a suitable organization of CoP internal activities,

and regular adaption and improvement. Highly influ-

ential variables that can impact many other aspects are

the CoP governance, organization, and skilled initia-

tors and leads. Many factors influencing CoP success

in scaled agile environments, like regular adaptation

and improvement, can be shaped by CoP leads or or-

ganizations. In addition, our findings show that estab-

lishing and cultivating a CoP in scaled agile settings

should be tailored to the specific context of an organi-

zation and community. Future research directions in-

clude expanding the study by interviewing more CoP

members instead of leads, validating our qualitative

findings through quantitative research, and using the

identified success factors as a basis to design solutions

for CoP implementation in large-scale agile environ-

ments. Aligned with this, we aim to provide detailed,

context-specific guidance to influence these factors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research has been funded by BMBF through

grant 01IS23069.

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

24

Affected Variable(s)/Factor(s)

(Influencing) Variable(s)/Factor(s) V9 V10 V11 V12 V13 V14 V15 V16 V17 V18 V19 V20 V21 V22 V23 V24 V25 V26 V27 V28 V29 V30 V31 V32

V1: Supporting organizational setting (B10) + + - +

V2: Virtual setting (B22) - + - -

V3: Geographical distribution (B21) - +

V4: Alternative formats (B13) -

V5: Organizational changes (B23) - + -

V6: Support for set-up and organization (SF20) - + + + +

V7: Supporting organizational culture (B7/SF10) + - + + + +

V8: Clear common goal and strategy (SF22) + + +

V9: (Attending) CoP members (B1/SF21) + - - -

V10: Time of members, initiators, leads (B2/SF16) + - + + +

V11: Diff. in set-up and organization (B3/B9) - - - - +

V12: (Perceived) value and need (B4/SF1) + + + + + +

V13: Engagement of CoP members (B5/SF12)

V14: Motivation of (potential) members (B6/SF6) + - +

V15: Management support (B8/SF4) + + - + + + +

V16: Time and effort req. for initiators/leads (B11) +

V17: Appropriate tool support (B12/SF13) - + + - + + +

V18: Skilled/passionate CoP initiators/leads (B14/SF9) + + - + + + + +

V19: Time and effort req. for participants (B15/SF24) - + - -

V20: Homogeneity of CoP members (B16) + - ± + +

V21: Assessment of CoP success/impact (B18/SF8) + + + + +

V22: Understanding of CoP concept (B19/SF19) + + + + +

V23: Steering (by management) (B24/SF15) - + - -

V24: Suitable org. of CoP internal activities (SF2) + - + + + - - + +

V25: Regular adaption and improvement (SF3) + - + + + +

V26: Shared underst. of CoP topic/purpose (B20/SF23) + + + +

V27: Suitable CoP structure and governance (SF5) + - + + + - - + +

V28: Suitable engag. and promotion activities (SF7) + + + + +

V29: Suitable establishment approach (SF11) ± + + + - ±

V30: Sustainable and efficient documentation (SF14) - + + + +

V31: Transp. and stakeholder engagement (SF17) - + + + +

V32: CoP cohesion (SF18) + - + + +

+ = increasing effect, - = decreasing effect

Table 5: Factors influencing the success of CoPs in scaled agile settings and how they are related.

Which Factors Influence the Success of Communities of Practices in Large Agile Organizations, and How Are They Related?

25

REFERENCES

Beck, K., Boehm, B., van Bennekum, A., Cockburn, A.,

Cunningham, W., Fowler, M., Grenning, J., Hunt, A.,

Jeffries, R., Kerievsky, J., Martin, R. C., Mellor, S.,

Schwaber, K., Sutherland, J., Thomas, D., and Ander-

son, D. R. D. (2001). Manifesto for agile software

development. https://agilemanifesto.org/. Accessed:

2025-01-22.

Detofeno, T., Reinehr, S., and Andreia, M. (2021). Tech-

nical debt guild: When experience and engagement

improve technical debt management. In Proc. of the

XX Brazilian Symposium on Software Quality, pages

1–10. ACM.

Digital AI (2023). 17th annual state of agile report.

https://info.digital.ai/rs/981-LQX-968/images/

RE-SA-17th-Annual-State-Of-Agile-Report.pdf?

version=0. Accessed: 2025-01-22.

Dikert, K., Paasivaara, M., and Lassenius, C. (2016). Chal-

lenges and success factors for large-scale agile trans-

formations: A systematic literature review. Journal of

Systems and Software, 119:87–108.

Dingsøyr, T. and Moe, N. B. (2014). Towards principles

of large-scale agile development: A summary of the

workshop at xp2014 and a revised research agenda. In

Proc. of the 13th Int. Conf. on Agile Software Devel-

opment 2014, pages 1–8. Springer.

Disciplined Agile (2024). Communities of prac-

tice. https://www.pmi.org/disciplined-agile/people/

communities-of-practice. Accessed: 2025-01-22.

Fontaine, M. A. and Millen, D. R. (2004). Understanding

the benefits and impact of communities of practice. In

Knowledge networks: Innovation through communi-

ties of practice, pages 1–13. IGI Global.

Fontana, A. and Frey, J. H. (2000). The interview: From

structured questions to negotiated text, volume 2.

London.

Geffers, K. (2024). Overcoming people-related challenges

in large-scale agile transformations: The role of on-

line communities of practice. In Proc. of the 32nd

European Conf. on Information Systems.

Highsmith, J. A. (2002). Agile software development

ecosystems. Addison-Wesley Professional.

Jassbi, A., Jassbi, J., Akhavan, P., Chu, M.-T., and Piri, M.

(2015). An empirical investigation for alignment of

communities of practice with organization using fuzzy

delphi panel. Vine, 45(3):322–343.

Kitchenham, B. and Pfleeger, S. L. (2002). Principles of sur-

vey research: part 5: populations and samples. ACM

SIGSOFT Software Engineering Notes, 27(5):17–20.

Kniberg, H. and Ivarsson, A. (2012). Scaling agile @spo-

tify. https://blog.crisp.se/wp-content/uploads/2012/

11/SpotifyScaling.pdf. Accessed: 2025-01-22.

Kopf, M., Sauermann, V., and Frey, F. (2018). Implement

communities of practice in an agile it environment.

In Proc. of the 23rd European Conf. on Pattern Lan-

guages of Programs, pages 1–9.

Korbel, A. (2014). Using communities of practice for align-

ment and continuous improvement at DigitalGlobe.

Agile Alliance.

K

¨

ahk

¨

onen, T. (2004). Agile methods for large

organizations-building communities of practice. In

Agile Development Conf., pages 2–10. IEEE.

LeSS (2024). Communities of practice. https://less.works/

less/structure/communities. Accessed: 2025-01-22.

Miles, M., Huberman, A., and Salda

˜

na, J. (2014). Quali-

tative data analysis a methods sourcebook. Thousand

Oaks, Califorinia SAGE Publications, Inc.

Monte, I., Lins, L., and Marinho, M. (2022). Communi-

ties of practice in large-scale agile development: A

systematic literature mapping. In Proc. of the XVLIII

Latin American Computer Conf. 2022, pages 1–10.

IEEE.

Myers, M. D. and Newman, M. (2007). The qualitative in-

terview in is research: Examining the craft. Informa-

tion and organization, 17(1):2–26.

Ojasalo, J., Wait, M., and MacLaverty, R. (2023). Facil-

itating communities of practice: A case study. The

Qualitative Report, 28(9).

Paasivaara, M. and Lassenius, C. (2014). Communities of

practice in a large distributed agile software develop-

ment organization – case ericsson. Information and

Software Technology, 56(12):1556–1577.

Runeson, P. and H

¨

ost, M. (2009). Guidelines for conduct-

ing and reporting case study research in software engi-

neering. Empirical software engineering, 14(2):131–

164.

SAFe (2023). Communities of prac-

tice. https://scaledagileframework.com/

communities-of-practice/. Accessed: 2025-01-

22.

Salda

˜

na, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative re-

searchers. SAGE publications Ltd.

Seaman, C. B. (1999). Qualitative methods in empirical

studies of software engineering. IEEE Transactions

on software engineering, 25(4):557–572.

ˇ

Smite, D., Moe, N., Floryan, M., Lavinta, G., and

Chatzipetrou, P. (2020). Spotify guilds: When the

value increases engagement, engagement increases

the value. Communications of the ACM.

ˇ

Smite, D., Moe, N. B., Levinta, G., and Floryan, M.

(2019a). Spotify guilds: How to succeed with knowl-

edge sharing in large-scale agile organizations. Ieee

Software, 36(2):51–57.

ˇ

Smite, D., Moe, N. B., Wigander, J., and Esser, H. (2019b).

Corporate-level communities at ericsson: Parallel or-

ganizational structure for fostering alignment for au-

tonomy. Agile Processes in Software Engineering and

Extreme Programming, pages 173–188.

Tobisch, F., Schmidt, J., and Matthes, F. (2024). Investigat-

ing communities of practice in large-scale agile soft-

ware development: An interview study. In Proc. of the

25th Int. Conf. on Agile Software Development 2024,

pages 3–19. Springer, Nature.

Van Oosterhout, M., Waarts, E., and Van Hillegersberg, J.

(2006). Change factors requiring agility and implica-

tions for it. European journal of information systems,

15(2):132–145.

Wenger, E., McDermott, R., and Snyder, W. M. (2002). Cul-

tivating communities of practice: A guide to manag-

ing knowledge, volume 4. Harvard Business School

Press Boston.

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

26