How Many Times Do I Need to Say, ‘It Is Me’? Investigating

Two-Factor Authentication with Older Adults in Norway

Way Kiat Bong

a

and Yuan Jing Li

Department of Computer Science, OsloMet – Oslo Metropolitan University, Pilestredet 35, Oslo, Norway

Keywords: Two-Factor Authentication, Usability, Mobile Applications, Elderly People, Older Adults.

Abstract: We will have fewer healthcare personnel per older adult in the future. The use of assistive technology has

been introduced to change the ways in which elderly care function, considering a more sustainable caregiving

system. However, with the growing threats in cybersecurity, assistive technologies must be implemented with

strong protective measures to ensure the privacy and safety of the elderly population. Two-factor

authentication (2FA) has been implemented in most technologies used today, but not in assistive technologies.

Research has also shown that 2FA methods can sometimes be user-unfriendly. Hence, in this study, we aim

to explore the user experiences and attitudes of older adults in Norway towards performing 2FA, hoping that

our findings can inform the implementation of assistive technologies. Through user testing and interviews

with eight older adults, we found that 2FA methods using the physical bank code device and SMS verification

were preferred. The perception of user-friendliness varied; Some prioritized ease in performing 2FA, while

others valued familiarity, focusing more on avoiding mistakes. Based on our findings, we intend to implement

the proposed 2FA methods into commonly used assistive technologies within the Norwegian caregiving

system and evaluate these methods with a larger sample of older adults.

1 INTRODUCTION

The escalating number of ageing populations

worldwide presents a significant societal challenge.

According to World Health Organization (WHO,

2024a), this number is rising much faster than ever

before. By 2050, the population of older adults aged

60 years and above will double, reaching 2.1 billion.

The population of those aged 80 years and above will

triple, reaching 426 million. In many countries,

assistive technologies have been introduced and

implemented in addressing this challenge. WHO

(2024b) defines assistive technologies as

technologies that can “help maintain or improve an

individual’s functioning related to cognition,

communication, hearing, mobility, self-care and

vision, thus enabling their health, well-being,

inclusion and participation”. Consequently, older

adults become one of the primary user groups of

assistive technologies, as they age and face certain

functional and cognitive decline.

The contributions of assistive technologies to

improved health and quality of life among older

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3714-123X

adults are evident (Fotteler et al., 2023; Sánchez et al.,

2017). However, research has shown that assistive

technologies used by older adults very often either

lack a safety mechanism (Sánchez et al., 2017), or the

authentication system presents usability issues for

older adults, which result in them needing assistance

from others (Ophoff & Renaud, 2023). Internet of

Things (IoT) devices for instance, have been widely

utilized in smart home solutions as assistive

technologies for older adults. Many of them pose

significant concerns regarding privacy and security

because they lack of safety and security mechanism

such as authentication (Paupini et al., 2022; Wilson,

2024).

Authentication is a crucial mechanism to ensure

the right person has the right access. It has been

becoming more important than ever, especially with

the growth threats in cybersecurity nowadays.

Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3, 2023)

reported an increase of 14% in incidents where older

adults were fraud victims over internet, with a total

loss of USD 3,427,717,654. For older adults residing

in European Union Member States, Iceland and

Bong, W. K. and Li, Y. J.

How Many Times Do I Need to Say, ‘It Is Me’? Investigating Two-Factor Authentication with Older Adults in Norway.

DOI: 10.5220/0013206500003938

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2025), pages 25-34

ISBN: 978-989-758-743-6; ISSN: 2184-4984

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

25

Norway, Kemp and Erades Pérez (2023) also reported

instances of online fraud among older adults aged 65

and above. However, this group suffered less online

frauds as compared to younger age groups, and this

particular finding did not take into account factors

such as internet usage and online shopping, which

could potentially clarify the varying rates observed

between older adults and younger adults.

To enhance the security of authentication

mechanisms, two-factor authentication (2FA) has

been extensively implemented. Some examples of

2FA methods include physical tokens, biometric

verification, and SMS verification codes. These

methods combine something the user knows (like a

password) with something the user has (like a

physical token or a verification app on smartphone),

providing an additional layer of security. In Norway,

one of the most common 2FA methods is the use of a

bank ID. Users can verify their identity either by

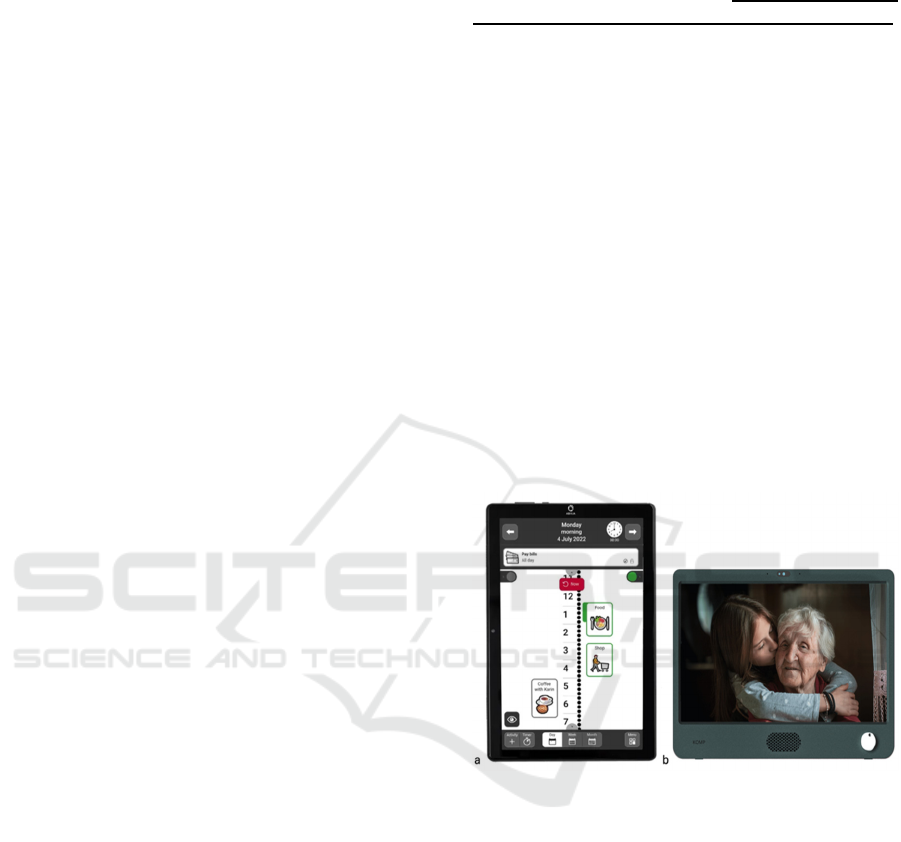

approving access via their bank ID app (see Fig. 1a

and 1b), or by entering a code generated on a physical

bank code device (see. Fig. 1c).

Figure 1(a) and (b): The bank ID app, where users first

confirm their identity and then return to the application to

enter their personal password, (c): Physical bank code

device that generates a six-digit code when prompted.

Research has been conducted to investigate the

use of 2FA among older adults. Das et al. (2020)

highlighted the lack of inclusive design in methods

for 2FA. They proposed design modifications to

enhance the use of 2FA among older adults, which

include confirming registration and increasing the

size of a USB-C security key to make it more

acceptable for older adults. As mentioned earlier, in

Norway we have been practising different methods of

2FA, making their findings about the USB-C security

key less relevant. To the best of our knowledge, no

usability evaluations have been conducted with older

adults regarding their user experience with these 2FA

methods. Moreover, there have not been many studies

focusing on the implementation of 2FA onto the use

of assistive technologies, which is a growing trend

worldwide due to the increasing ageing population.

Therefore, in this study, we aim to explore the

user experiences and attitudes among older adults in

Norway towards performing 2FA. Specifically, we

hope that the findings of this study can inform the

implementation of assistive technologies, as many of

the assistive technologies in use today lack an

authentitication mechanism that can ensure a more

secured use among the users.

2 METHODOLOGY

In this study, we conducted one-to-one user testing

sessions to observe how older adults performed 2FA.

This approach allowed us to identify usability issues

that these older adults encountered when using

different methods of 2FA. During the session, we also

asked the participants questions concerning their user

experiences and attitudes towards those methods and

2FA in general using a semi-structured interview

guide.

2.1 Recruitment and Ethical

Considerations

Participants were recruited via convenient sampling

(Sedgwick, 2013), as they were easily accessible and

met the inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria

include aged 65 and above (an age group that begins

to use assistive technologies according to a report by

Helsedirektoratet (2023)), being home-dwelling (one

of the common factors older adults using assistive

technologies) and having good cognitive function (as

they are the one performing 2FA and not relying on

others, such as next-of-kin).

The participants were first briefed about the study

during the recruitment process. A consent form was

then presented, detailing the user testing process and

expectations for their participation. As testing all

methods of 2FA could be time-consuming and

potentially overwhelming, we purposefully informed

them that they could take a break whenever needed,

or even withdraw from the study if they felt

uncomfortable continuing with the user testing. All

participants’ consent had to be obtained before we

began conducting the user testing. Prior to starting

data collection, we obtained approval for assessment

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

26

concerning data collection from Sikt – Norwegian

Agency for Shared Services in Education and

Research as it involved collecting personal data.

2.2 Data Collection and Analysis

We started by gathering demographic information

from each participant that could be relevant for data

analysis, which included age, education, employment

before retirement and so on. To access their skills in

using general Information and Communication

Technologies (ICT), we asked them to rate

themselves in on a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 indicating

very poor skills in using ICT and 10 indicating

advanced ICT proficiency. In addition to that, we

were also interested in their experiences with assistive

technologies and performing 2FA. Lastly, we asked

them to rate their concern about privacy and

cybersecurity on a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 being not

concern at all and 10 being extremely concern. When

explaining assistive technologies to the participants,

we provided examples such as smart watch, smart

home devices, safety alarms, and devices equipped

with GPS, all of which aid individuals in living more

independently and safely. They were also shown

some examples of 2FA, with the most common ones

in Norway being the bank ID and bank code device.

During the user testing, all participants were

asked to use five methods of 2FA, and we observed

how they completed the process. These methods

included in-app verification (without a code, see Fig.

2a), email verification (where users had to retrieve a

verification code from an email then enter it into the

requesting application, see Fig. 2b), SMS verification

(similar to email, but the participants received the

code via SMS text; see Fig. 2c), and lastly bank ID

(both via the app and the physical bank code device;

see Fig 1a, b and c). Except for the bank code device,

all interactions took place on a smartphone as we did

not provide any additional devices such as a laptop

for email verification. This is because older adults in

Norway normally do not own or use laptops at home,

as they can rely solely on their smartphones for

everyday digital transactions.

After each method, we asked them questions

related to their user experience and attitudes. For

examples, “What do you think about the process just

now, in terms task difficulty”, “How do you feel

about receiving a verification code via

email/app/SMS?” and “What do you think of this

extra step of verifying yourself?”. At the end of each

method, the participants were asked to complete the

System Usability SUS questionnaires. Each user

testing took around 60 to 90 minutes.

Qualitative data were analysed using thematic

analysis (Clarke & Braun, 2017), as we aimed to

identify similarities and differences in the

participants’ user experiences and attitudes towards

performing 2FA, in relations to their demographic

backgrounds.

Given

its

flexibility,

this

approach

is

Figure 2(a): In-app verification where users only had to click on confirming their identify, (b): Verification code sent to an

email with instructions, (c): Verification code sent via SMS.

How Many Times Do I Need to Say, ‘It Is Me’? Investigating Two-Factor Authentication with Older Adults in Norway

27

were recorded and transcribed. After being

familiarizing ourselves with the qualitative data, we

generated codes and themes based on the data. For

SUS scores, we calculated the average scores for all

ten statements for each method.

3 RESULTS

A total of eight older adults participated in this study.

All of them had experience with 2FA, either they did

it themselves or with help and assistance from

someone. In Norway, many services require 2FA, so

it was not surprising that all of them had some

experience with it; with internet banking being one

example. However, not all 2FA methods were equally

familiar to them. SMS verification and bank ID

verification via the physical code device were

considered the most common methods among them.

Although all of them use smartphone daily, they rated

their ICT skills very differently. This could be due to

their use of technologies prior to retirement, in

addition to how they used their smartphones. Despite

the varied self-rated ICT skills, when it came to

concerns about privacy and cybersecurity, none of

them rated it below 8. Only P1 and P8 have used

assistive technologies, i.e., smart watches. Table 1

summarizes the participants’ profiles.

3.1 Usability

All participants managed to perform all five 2FA

methods with minimal difficulty. Among these

methods, they were most familiar with using the

physical bank code device, followed by the SMS

verification method. Almost all of them required a bit

guidance, primarily on understanding where they

received the verification code, especially for email

and in-app methods. The reason is that they had

limited experience using these two methods. Both P1

and P5 mentioned that they rarely used email for

anything nowadays. P5 even shared his past

experiences with email verification where he had

trouble with receiving the verification code and

entering it before it got expired. On the other hand,

P4, who had previously worked as a doctor, was

comfortable with using email as checking emails was

not unfamiliar to him. We observed that most

participants were slightly irritated when required to

check their email for the verification code, compared

to checking an SMS message for the code. Upon

asking, they explained that they used SMS messages

far more frequently than email. They rarely checked

emails nowadays, so the interface did not seem

familiar to them. None of the participants experienced

any difficulties using the SMS verification method.

The only minor annoyance for some was the need to

switch between apps to retrieve the SMS verification

code and input it into the app requesting the code. To

remember the code, some participants also jotted it

down on paper. This need to switch between apps and

Table 1: Participants’ profile.

Age Gender Smartphone

use

Education

level

Employment

before

retirement

ICT

skills

(1 to

10)

Experience

in using

assistive

technologies

Experience

in

performing

2FA

Concern

about privacy

and

cybersecurity

(1 to 10)

P1 66 F Everyday High

school

House

kee

p

in

g

3 Yes Yes 8

P2 67 M Everyday High

school

Cook 1 No Yes 8

P3 65 F Everyday Bachelor House

keeping

1 No Yes 9

P4 80 M Everyday Master Doctor 6 No Yes 10

P5 68 M Everyday High

school

Freelance in

ICT

6 No Yes 9

P6 70 M Everyday High

school

Engineer 6 No Yes 9

P7 72 F Everyday High

school

Customer

service

8 No Yes 9

P8 75 M Everyday Master Researcher 9 Yes Yes 10

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

28

write down the code was also noted in the case of

email verification.

Although most participants needed some

explanations for in-app verification and bank ID

verification, they found these methods to be very easy

and intuitive. They took a bit little more time to

understand the process and ensure that they were

doing everything correctly. Their unfamiliarity with

these methods, coupled with a fear of making

mistakes, accounted for this. However, they

demonstrated a completely different level of

confidence when verifying using the physical bank

code device.

The SUS results are consistent with our

observations and some clarifications we received. We

calculated the average scores of all SUS statements

for all methods. The results are presented in Table 2.

As shown in the table, the 2FA methods using the

physical bank code device and SMS verification

scored very high in terms of their usability (high for

positive responses in odd-numbered statements and

low for negative responses in even-numbered

statements). Email verification was the least

favoured, as indicated by both the SUS scores, the

interview results, and through observation.

Interestingly, despite generally high usability

scores, SMS verification received lower scores on

statements 5 and 6 compared to in-app verification.

This may be due to the extra effort required by older

adults to write down the verification code. In-app

verification was commented on by most participants

as being very convenient. The verification

notification appeared on the screen, and users only

needed to click on it, and then click on "Yes" (see Fig

2a) when asked to verify their identity. In terms of

preferences, we noticed that most participants valued

familiarity over ease of performing the 2FA methods.

This can be observed when looking at the scores for

statements 5 and 6 (which lean more towards ease),

and 7, 9, and 10 (which lean more towards

familiarity), along with the clarifications we received.

3.2 Thematic Analysis

We identified three themes in total. The first one is

“Feeling the need as older adults”. Some of the

codes that were generated and organized under this

theme were “protecting their identity and information

better”, “feeling safer”, “is important and necessary”,

“user-friendliness”, “writing it down”, “asking help

to ensure safety and protection” and “being afraid of

online frauds”. All participants expressed that they

perceived 2FA as crucial mechanism for protecting

them when using assistive technologies, as well as

other digital technologies in general. This attitude

was consistent across all participants, regardless of

their demographic background such as age, level of

education and ICT skills. Almost all of them

understood why 2FA was required. For P3, she

mentioned, “I don’t really know (the reason). I mostly

ask my son to help with new technology thing.”.

However, she has been told many times by peers and

family members that online frauds occur, and older

adults are one of the target groups. For P6, he was

sometimes

frustrated with performing 2FA, but he

Table 2: SUS results for each two-factor authentication method.

Average scores for each method

SUS statements (Scale 1 to 5, 1 is strongly

disagree an

d

5 is strongly agree)

In-app Email SMS Bank ID

(app)

Bank code

device

1. I think that I would like to use this system

fre

q

uentl

y

.

3.00 3.25 3.88 4.00 4.50

2. I found the system unnecessarily complex. 1.25 1.63 1.00 1.50 1.00

3. I thought the system was easy to use. 3.00 2.75 3.88 3.75 4.63

4. I think that I would need the support of a

technical

p

erson to

b

e able to use this s

y

stem.

1.88 2.50 1.38 2.75 1.38

5. I found the various functions in this system

were well inte

g

rated.

2.88 3.00 2.50 3.25 3.25

6. I thought there was too much inconsistency in

this system.

1.38 3.13 1.63 2.25 1.13

7. I would imagine that most people would learn to

use this system very quickly.

3.75 3.75 4.38 4.00 4.75

8. I found the system very cumbersome to use. 1.50 3.00 1.25 1.75 1.00

9. I felt very confident using the system. 3.00 2.75 3.75 2.88 4.00

10. I needed to learn a lot of things before I could

get going with this system.

1.75 2.38 1.13 1.75 1.00

How Many Times Do I Need to Say, ‘It Is Me’? Investigating Two-Factor Authentication with Older Adults in Norway

29

knew that it was necessary, “How many times do I

need to say, ‘it is me!’…it is like those websites keep

on asking if I were human!”.

Besides the need of 2FA to provide safer use of

digital technologies for older adults, there is also a

need that for these authentication methods to be user-

friendly for them. When comparing all the methods

they tested, they frequently commented on the

inconvenience of needing to switch to a specific app,

read the code sent there, and then switch back to the

app that requested for the code and enter it there. We

observed that some of them were irritated by this

back-and-forth process as they couldn’t remember the

code. Some noted the code on a piece of paper, even

without our instruction to do so. We clarified with

them after the testing if this was a practice they

always had, and their answer was yes. They have had

bad experiences in remembering the code and

switching in between apps, so writing the code down

became their preferred solution.

The second theme is “Preferring the old-

fashioned way despite downfalls”, with codes such

as “used it for many years”, “use daily”, “easier than

the app now”, “familiar”, “not new”, “less chance for

mistakes”, “small in size” and “lost it a few times”.

The physical bank code device appeared to be a

favourite among the participants. Based on our

observation, none of them had issues using the code

generated by the bank code device, and then entering

a password. When asked about their user experience,

they expressed that this method was the most familiar

method to them. A few mentioned its disadvantages,

which included the size of the device being too small

and the inconvenience of having to carry it around

when traveling. However, most participants still

preferred it over the newer version of the bank ID,

which is on an app. They felt that they would make

fewer mistake with a code device than with an app. “I

am so bad with new technologies and apps! If I drop

my bank code device somewhere, no one would know

who it belongs to. But if I drop my phone somewhere,

everything is in it! And I have read about phone being

hacked and stuff like this…”, expressed by P7. The

same pattern was observed in older adults’ preference

of receiving verification codes via SMS over in-app

verification, despite the fact that in-app verification

appeared to be more effortless to them.

Under this theme, we also noticed that most older

adults desired new technologies to consider their

existing everyday routines. While 2FA appears to be

something new in their lives, its implementation does

not have to be completely unfamiliar. For instance,

utilizing bank ID verification via the physical bank

code device could be an option that does not introduce

an entirely new concept to them. The same applies to

receiving verification code via SMS, as most of them

use SMS daily and felt safer using this method than

others. However, SMS phishing remains as a concern.

P7 found it challenging at times but reported that it

had become easier now after following some

guidelines, “I know that those that are not Norwegian

number are definitely spam, and usually one can tell

from the text they write. If I receive something

suddenly, like this code when I do not request for it,

then something must be wrong…”.

The third and last theme is “Variety in

preferences”. This theme was derived based on

codes illustrating contrasting opinions among the

participants, and therefore emphasizes on the

importance of providing different alternatives to older

adults when performing 2FA. For instance, some

would prioritize the 2FA methods being effortless,

while the others would rather spend more effort to

ensure mistakes were not made. When asked about

what they deem important, all participants agreed on

the importance of 2FA for safety and cybersecurity.

However, their criteria for assessing different 2FA

methods varied individually. Even what they

perceived as “user-friendly” was different. P8

mentioned, “If I need to choose something that is

user-friendly, I will choose a method that is simple,

easy to understand......Like just now (refers to in-app

verification and bank ID verification via app), I need

to only press one button to confirm”. Among all

participants, P1 shared the same sentiment as P8, “I

prefer the first one (referring to in-app verification),

I don’t need to write anything… So even it is more

complicated to use another app (refer to the app to

verify identity), need to open it, press and get verified,

it was easier for me”. Both of them also appreciated

that the instructions for in-app verification were very

simple and straightforward.

On the other hand, several participants equated

user-friendliness with familiarity and safety in

performing 2FA methods. For instance, P5 compared

2FA methods after performing them, and commented,

“These (referring to methods using verification code,

such as SMS verification, email verification and bank

ID using the physical code device) take always more

time for me, but they work, just…. using some time, and

the verification code comes fast! (Referring to that the

extra time spent wasn’t that much of an effort)

”. This

same opinion was also held by P3, P4 and P7. P2 and

P6 felt that all methods were almost the same in terms

of user-friendliness. However, for P6, one unique

factor made a difference, “I do not like this (referring

to relying on his smartphone) very much, because if I

forget the phone where I go, then it is not possible to

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

30

log in…”. He expressed that he disliked relying too

heavily on smartphones and therefore tended to be

unaware of where his phone was most of the time.

4 DISCUSSION

After evaluating five different 2FA methods with

eight participants and gaining more in-depth opinions

from them through a semi-structured interview, we

managed to identify the pros and cons of each method

along with deeper insights concerning their opinions

and attitudes towards 2FA authentication, privacy and

cybersecurity.

Despite there being obvious preferred 2FA

methods among the participants, they prioritized

differently in terms of what was important to them,

which included factors such as effort and confidence in

conducting the 2FA. The 2FA methods using the

physical bank code and SMS verification were

preferred by most participants, while email was the

least favoured. In Das et al. (2020)’s study, they

identified “device compatibility” as one of the factors

preventing older adults from adopting 2FA. Most of

their participants only used tablet and smartphone, and

the Yubico Security Key device they tested was neither

compatible with a tablet nor a smartphone. In our

study, since the bank code device has been widely

implemented in Norway for various technologies, such

as internet banking and the tax system, these older

adults used it frequently and therefore, device compati-

bility was not an issue. In fact, due to its compatibility,

this method was considered as one of the most familiar

and hence, safest among these participants.

Email has been becoming less popular among older

adults as new media platforms have replaced email

communication (Nguyen et al., 2021). Older adults in

this study also reported a decreased use of email,

making email verification less convenient and user-

friendly for them. As email can contain more text than

a standard SMS message, they typically include more

instructions in addition to providing a 2FA verification

code. Das et al. (2020) reported that instructions could

impact on how older adults perceived 2FA. In our

study, participants preferred straightforward

instructions, like those they encountered in SMS

verification and in-app verification.

4.1 Proposed Design Considerations

When implementing 2FA in assistive technologies,

we propose the following three designs

considerations based on our findings. To better

illustrate the concept, we couple them with existing

assistive technologies commonly used in Norway.

The first design consideration is to utilize commonly

used technologies rather than creating new ones.

More precisely, we recommend receiving verification

codes via SMS and a bank code device, as opposed to

verifying identity through a bank ID app or via email.

For instance, when logging into the user profile on a

touch screen-based, compensation and wellness type

of assistive technology named MEMOplanner

Medium (see Fig 3a)(Abilia, 2024), users can first

enter a verification code sent to their phone via SMS,

or retrive the code generated on their bank code

device, then enter their password. This technology is

a time and planning aid that compensates for memory

deterioration in older adults. Since it utilizes a large

touch screen for interaction, we believe 2FA methods

with which users are familiar with, both retrieving

and entering a verification code are most suitable.

Comparing these two 2FA methods, the physical

bank code device is safer than the SMS verification.

SMS verification has its shortcomings, as SMS

phishing can occur and the SMS technology itself has

many vulnerabilities (Drake & Gauravaram, 2019).

Figure 3: (a) MEMOplanner Medium from (Abilia, 2024),

(b): KOMP from (Kompany, 2024).

This design consideration is particularly

important, given that introducing a new, unfamiliar

assistive technology can be intimidating to older

adults (Glomsås et al., 2021). To minimize their fear

of accepting and learning new technologies, we can

utilize existing one, for instance SMS verification and

bank ID verification via the physical bank code

device. Almost half of our participants perceived such

methods as more user-friendly, considering they felt

more confident in performing them. They preferred

the methods with which they were familiar, even if

these could require extra efforts. For them, feeling

secure in their use of technology and avoiding

mistake were more important. This finding is

consistent with that of Kuerbis et al. (2017) who

identified personal motivational factors among older

How Many Times Do I Need to Say, ‘It Is Me’? Investigating Two-Factor Authentication with Older Adults in Norway

31

adults in their technology use (such as previous

experience, attitudes, complexity/ usability, etc.), and

design principles summarized by Iancu and Iancu

(2020) which need to take their cognitive abilities into

account. However, it is important to note that

recommending these two methods does not imply that

only these methods shall be considered, and not the

others. Instead, it simply means that these methods

should be prioritized when not all methods can be

implemented. We discuss more about this finding in

the third design consideration.

The second design consideration is to avoid

unnecessary typing when performing 2FA. This is

particularly suitable for assistive technologies that

either do not have a touch screen, or have a touch

screen that is small. A social contact type assistive

technology named KOMP falls into that category (see

Fig 3b). It is a one-button device with a single screen,

roughly the size and shape of a small TV (Kompany,

2024). Older users can receive calls, text and image

messages from their family, friends and caregivers

via KOMP. Using the only button on KOMP, older

users can turn the device on and off, and control the

volume. We suggest that when logging onto KOMP,

this button can also be used to navigate between

options on the screen during 2FA. The 2FA methods

could be in-app verification or bank ID via the app,

which do not require any typing. Users simply select

the correct option.

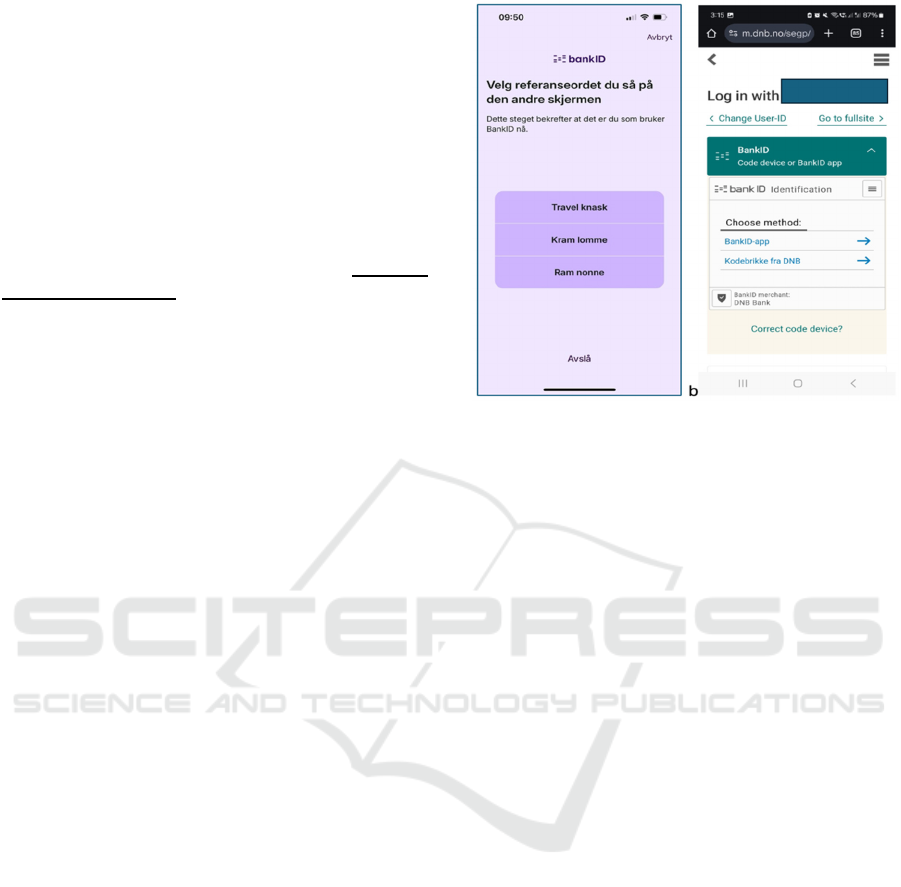

The latest design of Bank ID via the app (lauched

after we completed all user testing) offers the option

to perform 2FA by selecting the matching verification

code, eliminating the need for typing, as illustrated in

Figure 4. Older adults' fear of making mistakes

increases when they have to interact with small user

interfaces (Iancu & Iancu, 2020), (Iancu & Iancu,

2020). Our observations corroborate this finding.

Lastly, we highly recommend that, whenever

possible, several 2FA alternatives should be

provided. Older adults constitute a very diverse user

group. Although we observed certain commonalities

among them, there were still significant differences,

particularly in how they perceived user-friendliness.

All participants in this study found in-app verification

to be effortless as it only required one button click.

However, not all of them perceived it as a user-

friendly 2FA method. For some participants, they

needed to spend more time and effort reading the

instructions on the screen to ensure they didn't make

mistakes. This was seen as less user-friendly than

other methods, such as SMS verification and bank ID

verification using the physical bank code device.

Figure 4: (a) Bank ID verification using app where users are

asked to choose matching verification code, (b) Bank ID

verification allows users to choose verification via app or

physical code device.

The design offering several alternatives can be

seen in Fig 4b. When accessing internet banking,

users are always asked to choose a method for their

bank ID verification, which could be via an app or a

physical bank code device. This kind of design can

also be implemented in assistive technologies

accordingly, based on the interaction styles, size, and

type of devices. When assistive technologies adopt a

small touchscreen (like smart home devices such as

robot vacuum cleaners and smart door locks utilizing

apps on smartphones) or have no touchscreen at all

(like KOMP and medicine dispensers), then the in-

app verification and bank ID verification via an app

that requires no typing should be included. On the

other hand, when the assistive technologies have a

large touchscreen with an on-screen keyboard, they

can offer all methods if possible.

4.2 Privacy and Cybersecurity

Concern

In terms of privacy and cybersecurity concerns, all

participants reported high levels of concern, which is

why they would always opt for 2FA. In a study also

conducted in Norway, Ellefsen and Chen (2022)

obtained similar findings, with older adults seeing

more pros than cons in 2FA. All of them performed

2FA despite initially finding it tedious and

experiencing a delay in the login process due to the

extra step.

Our finding is contrary to previous study by

(Drake & Gauravaram, 2019), which highlighted the

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

32

importance of usability over privacy and security. All

of our participants acknowledged the importance of

having 2FA in the daily use of technologies. This

discrepancy in findings could be attributed to the

accelerated digitalization due to the pandemic and,

more recently, the emergence of artificial

intelligence. During the pandemic, restrictions led to

the digitalization of many activities, necessitating the

broader use of assistive technologies among older

adults (Mendoza-Holgado et al., 2024). Many

phishers utilized artificial intelligence to create

websites, emails, and other digital content that appear

realistic but are fake to victimize users (Eze &

Shamir, 2024). Among the targeted demographics,

older adults are frequently victimized (Grilli et al.,

2021). Participants in our study reported hearing

similar stories through their peers and family

members, as well as on social media.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we aim to explore the user experiences

and attitudes among older adults in Norway towards

performing 2FA. By evaluating different 2FA

methods with eight older adults, we investigated how

they perceived the usability of each method. We hope

that our findings can inform the implementation of

assistive technologies. Our findings indicate that bank

ID verification using the physical bank code device

and SMS verification were preferred by most

participants. However, participants perceived user-

friendliness in different ways. Some prioritized

avoiding mistakes when performing 2FA, while

others valued effortlessness more. Despite their

varied socio-demographic backgrounds, all

participants understood the importance of performing

2FA and expressed high concern for privacy and

cybersecurity.

This study’s biggest limitation is the small sample

size. The sample size of eight is small for assessing

the usability of 2FA methods, particularly given that

there were five methods in total and that familiarity

with some of the 2FA methods varied among these

participants. Hence, possible bias could occur.

However, at this phase of the study, our aim was to

gather qualitative data through observation of all

participants performing each 2FA method, and to

gain further insights through follow-up interviews.

Besides, some might argue that the choice of using

SUS could be questionable. However, after reviewing

its pros and cons (Drew et al., 2018), we concluded

that SUS was suitable as we were comparing these

2FA methods based on user preference, which is

strongly related in their “success” in performing 2FA.

Another limitation is that we did not include any

biometric-oriented 2FA methods. The reason for this

is that such methods are device-dependent, where

users can also save their passwords in the devices they

use. In this study, we wanted to focus solely on

methods that are not device-dependent with saved

passwords, and therefore require an additional step

and effort from older adults.

In the future, we hope to conduct more

evaluations involving larger, more diverse participant

groups, as the findings here represent a small group

of participants with limited extent of diversity. Based

on more comprehensive finding, we can then

implement the proposed 2FA methods onto some

commonly used assistive technologies among older

adults in Norway and evaluate how the users

perceived their usability. It is worth noting that not all

banks around the world use a physical device for

2FA, and this method is not employed in all countries

either. Therefore, our findings cannot be generalized.

Nevertheless, we hope these findings can inspire

designers and policymakers to consider other

alternative methods when enforcing the use of 2FA

among older adults. By ensuring secure use of

assistive technologies, we can contribute to healthier

aging among older adults, reducing the likelihood of

older adults being victimized from cyberattacks, data

breaches and identity theft, among other privacy and

cybersecurity issues.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to express our gratitude to all

participants for sparing their valuable time and

demonstrating tremendous patience during this study.

We also appreciate them graciously allowing us to

conduct interviews and usability testing in their

homes.

REFERENCES

Abilia. (2024). MEMOplanner Medium | Abilia.

https://www.abilia.com/intl/our-products/cognition-ti

me-and-planning/memory-and-calendars/memoplanne

r-medium

Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The

journal of positive psychology, 12(3), 297-298.

Das, S., Kim, A., Jelen, B., Streiff, J., Camp, L. J., & Huber,

L. (2020). Why don’t older adults adopt two-factor

authentication? Proceedings of the 2020 SIGCHI

How Many Times Do I Need to Say, ‘It Is Me’? Investigating Two-Factor Authentication with Older Adults in Norway

33

Workshop on Designing Interactions for the Ageing

Populations-Addressing Global Challenges,

Drake, C., & Gauravaram, P. (2019). Designing a User-

Experience-First, Privacy-Respectful, high-security

mutual-multifactor authentication solution. Security in

Computing and Communications: 6th International

Symposium, SSCC 2018, Bangalore, India, September

19–22, 2018, Revised Selected Papers 6,

Drew, M. R., Falcone, B., & Baccus, W. L. (2018). What

does the system usability scale (SUS) measure?

validation using think aloud verbalization and

behavioral metrics. Design, User Experience, and

Usability: Theory and Practice: 7th International

Conference, DUXU 2018, Held as Part of HCI

International 2018, Las Vegas, NV, USA, July 15-20,

2018, Proceedings, Part I 7,

Ellefsen, J., & Chen, W. (2022). Privacy and Data Security

in Everyday Online Services for Older Adults.

Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on

Software Development and Technologies for

Enhancing Accessibility and Fighting Info-exclusion,

Eze, C. S., & Shamir, L. (2024). Analysis and prevention of

AI-based phishing email attacks. Electronics, 13(10),

1839.

Fotteler, M. L., Kocar, T. D., Dallmeier, D., Kohn, B.,

Mayer, S., Waibel, A.-K., Swoboda, W., & Denkinger,

M. (2023). Use and benefit of information,

communication, and assistive technology among

community-dwelling older adults–a cross-sectional

study. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 2004.

Glomsås, H. S., Knutsen, I. R., Fossum, M., & Halvorsen,

K. (2021). ‘They just came with the medication

dispenser’-a qualitative study of elderly service users’

involvement and welfare technology in public home

care services. BMC health services research, 21(1), 1-

11.

Grilli, M. D., McVeigh, K. S., Hakim, Z. M., Wank, A. A.,

Getz, S. J., Levin, B. E., Ebner, N. C., & Wilson, R. C.

(2021). Is this phishing? Older age is associated with

greater difficulty discriminating between safe and

malicious emails. The Journals of Gerontology: Series

B, 76(9), 1711-1715.

Helsedirektoratet. (2023). Bruk av velferdsteknologi -

Helsedirektoratet. Retrieved 13 September from

https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/rapporter/omsorg-20

20--arsrapport-2020/statistikk/bruk-av-velferdsteknol

ogi

Iancu, I., & Iancu, B. (2020). Designing mobile technology

for elderly. A theoretical overview. Technological

Forecasting and Social Change, 155, 119977.

IC3. (2023). Federal Bureau of Investigation Elder Fraud

Report 2023. https://www.ic3.gov/media/PDF/Annual

Report/2023_IC3ElderFraudReport.pdf

Kemp, S., & Erades Pérez, N. (2023). Consumer Fraud

against Older Adults in Digital Society: Examining

Victimization and Its Impact. Int J Environ Res Public

Health, 20(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075404

Kompany. (2024). Komp - The one-button computer.

https://komp.family/en/

Kuerbis, A., Mulliken, A., Muench, F., Moore, A. A., &

Gardner, D. (2017). Older adults and mobile

technology: Factors that enhance and inhibit utilization

in the context of behavioral health.

Mendoza-Holgado, C., García-González, I., & López-

Espuela, F. (2024). Digitalization of Activities of Daily

Living and Its Influence on Social Participation for

Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Scoping

Review. Healthcare,

Nguyen, M. H., Hargittai, E., Fuchs, J., Djukaric, T., &

Hunsaker, A. (2021). Trading spaces: How and why

older adults disconnect from and switch between digital

media. The Information Society, 37(5), 299-311.

Ophoff, J., & Renaud, K. V. (2023). Universal design for

website authentication: views and experiences of senior

citizens. 2023 38th IEEE/ACM International

Conference on Automated Software Engineering

Workshops (ASEW),

Paupini, C., van der Zeeuw, A., & Fiane Teigen, H. (2022).

Trust in the institution and privacy management of

Internet of Things devices. A comparative case study of

Dutch and Norwegian households. Technology in

Society, 70, 102026. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.techsoc.2022.102026

Sánchez, V. G., Taylor, I., & Bing-Jonsson, P. C. (2017).

Ethics of smart house welfare technology for older

adults: a systematic literature review. International

journal of technology assessment in health care, 33(6),

691-699.

Sedgwick, P. (2013). Convenience sampling. Bmj, 347.

WHO. (2024a, 1st October). Ageing and health. Retrieved

1st October from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-

sheets/detail/ageing-and-health

WHO. (2024b, 2nd January). Assistive Technology.

Retrieved 2nd January from https://www.who.int/

news-room/fact-sheets/detail/assistive-technology

Wilson, T. (2024). The Unintended Harm of IoT Devices in

Assistive Technology Distribution Programs. 2024

IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy

Workshops (EuroS&PW),

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

34