Digital Platform-Based Value Creation in Micro-Enterprise Networks

Kaisa Liukkonen, Otto Nokkala and Jyri Vilko

Kouvola Unit, LUT University, Kouvola, Finland

Keywords: Digital Platforms, Value Creation, Micro-Enterprises, Value Networks, Collaboration, Social Interaction.

Abstract: Digital platform-based value creation allows micro-enterprises to cost-effectively share information within

their value networks. However, these enterprises face challenges due to limited resources and skills, making

network participation crucial for value creation. Digital platforms are generally accessible, offering micro-

enterprises practical tools for enhancing business operations and value creation. This study aims to examine

the value networks in the non-timber forest sector, exploring how sector participants create value and the

digital platforms they use. Conducted as qualitative research, the study combines a literature review with

empirical data. Findings reveal that digital platforms, including websites, social media, and communication

platforms, were primarily used for sales, marketing, and communication. However, digital platform use and

perceived value creation were low; companies attributed this to resource constraints and satisfaction with

current customer numbers.

1 INTRODUCTION

Digital platforms have made it easier for companies

to strengthen their networking and to manage the

collection and processing of large amounts of

information. This has changed the competitive

landscape of companies considerably, as the platform

economy is playing a larger role in daily business, and

the role of information and interaction has grown

significantly. (Stone et al. 2017; Park 2018)

For micro-enterprises aiming to grow their

customer base and communicate their business

through social interaction, it is easy to use digital

platforms that help to disseminate information to the

widest possible audience. The most typical platforms

for this purpose are service platforms such as

company websites and social media platforms

(Ohlsbom et al. 2024). However, micro-enterprises

face different challenges in using service platforms in

their business, and therefore their use may be limited

(Thrassou et al. 2020). Micro-enterprises often lack

expertise, innovation capacity and resources, which

are major constraints to their business development

(Konsti-Laakso et al. 2012).

There has been little research on the value creation

of microenterprises (Rashidirad & Salimian 2020).

Two strong needs have been identified for micro-

enterprise development, namely learning about

marketing and sales and network development

(Kuismanen et al. 2019).

The aim of this study is to find out what kind of

value network exists in the non-timber forest product

sector, how operators in the sector create value and

what kind of digital platforms they use to create value.

The study was conducted as qualitative research and

consists of a literature review and an empirical part.

In a case study, the non-timber forest product sector

was examined. In doing so, two value networks for

the sector were revealed and further information

about the digital platform usage in micro-enterprises

for value creation was gained.

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

2.1 Value Networks

In a value network, companies and consumers

interact to create value not only through independent

activities but through collaborative exchanges within

the network (Kothandaraman & Wilson, 2001). A

value network redefines the traditional supply chain

by focusing on customer priorities, aligning a

company’s operations and relationships to meet

genuine demand. This customer-centric approach

emphasizes collaboration, agility, scalability, and

rapid information flow. (Bovet & Martha, 2000)

Bovet and Martha (2000) suggest that value networks

202

Liukkonen, K., Nokkala, O. and Vilko, J.

Digital Platform-Based Value Creation in Micro-Enterprise Networks.

DOI: 10.5220/0013214900003929

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2025) - Volume 1, pages 202-209

ISBN: 978-989-758-749-8; ISSN: 2184-4992

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

enable high customer satisfaction and increased

competitiveness in dynamic business environments.

Collaboration between companies does also have a

known positive impact on value creation and

performance (Nielsen, 1988; Madhavan et al., 1998).

Value networks function as interconnected value

chains aiming to deliver the highest possible value to

the end user. Three core elements underpin this goal:

superior customer value, core capabilities, and strong

inter-company relationships. These “value drivers”

are essential for developing a product or service’s

entire value chain (Kothandaraman & Wilson, 2001).

For micro-enterprises, stakeholder cooperation is

crucial to business development. Research by

Kuismanen et al. (2019) indicates that the primary

needs of micro-enterprises include enhanced

marketing, sales skills, and networking. Limited

resources, expertise, and innovation capacity pose

significant barriers to innovation and growth (Konsti-

Laakso et al., 2012). Nonetheless, cooperation with

suppliers and customers has a positive effect on

performance (Zeng et al., 2010), and network

members’ shared objectives are closely linked to

improved network performance (Wincent, 2005).

Moreover, studies highlight a clear correlation

between the degree of networking and company

growth (Zhao & Aram, 1995).

Bovet and Martha (2000) propose a three-stage

framework for forming a value network: (1) customer

orientation, (2) activity and supplier alignment, and

(3) value flow. This process begins with

understanding customer needs, which informs the

company’s focus and aligns its operations and

supplier relationships accordingly. Realigning

processes, such as reorganizing production or

adjusting supplier contracts, enhances value flow to

customers. The dominant firm in the network benefits

from a competitive advantage, higher profits, and

market value. To understand value networks better, a

tool called value network analysis has been

introduced.

Value network analysis can be used to describe

the dynamics of value creation between the different

actors in the network from a commodity perspective

(Allee 2008). Value network analysis tells us where

in the value network a particular value is located and

how it is created. The value network analysis allows

a firm's management to distinguish between the basic

functions performed by the firm in the design,

production, marketing and distribution of a service or

product. (Peppard & Rylander 2006) Peppard and

Rylander (2006) outline a five-step approach which

can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1: Value Network Analysis.

Phase Description

1. Defining the

network

Identify which actors and

stakeholders should be part of

the value network analysis. In

this phase, the main actor of

the value network is also

identified, and the analysis is

structured around this actor's

p

erspective.

2. Defining the

actors

Understand the role and

significance of each actor

within the value network,

based on the main actor’s

p

erspective.

3. Defining the

actors perceived

value

Identify the dimensions and

sources of value for each actor

in the network.

4. Finding out

the interaction

between actors

Map the value flows between

actors, understanding how

value is transferred within the

network.

5. Picturing the

value network

and analysis

Create a final representation of

the actors and resource flows

in the value network. This

phase aims to reveal how

actors influence each other and

allows for analysis and

development of network

activities.

This five steps analysis starts by identifying the

key actor in the value network, followed by the

identification of the other actors. The actors in the

value network are all those members that have a direct

impact on the value delivered to the customer

(Peppard & Rylander 2006). The most important

actors that can be found in almost all value networks

are suppliers, competitors, manufacturers,

distributors and customers. Other actors may include

regulators, distribution channels, designers or

technology suppliers (Peppard & Rylander 2006).

Once the members of the value network have been

identified, an attempt is made to determine the

perceived value of the network members. Not all

members of the network benefit from being part of

the network. The disadvantages may be greater than

the benefits and it is therefore worth remembering

that not all members of the network are involved

voluntarily (Peppard & Rylander 2006). After

identifying the benefits and disadvantages, the aim is

to identify the interaction between the network

members. Interaction can take the form of sharing

information, services or goods, but the most

important thing at this stage is to identify the value

Digital Platform-Based Value Creation in Micro-Enterprise Networks

203

that the member brings to the network. The final step

in the analysis is the formation of an overall picture

of the network, i.e. the formation of a value network,

which is not addressed by Peppard and Rylander

(2006).

2.2 Digital Platforms in Value Creation

Digital platforms have transformed how companies

innovate and operate, with significant impacts on

networking, information processing, and competition

(Viitanen et al., 2017). Platforms today serve as

foundations for developing services, technology, and

products (Stone et al., 2017), marking a shift toward

the "platform economy" that leverages digitalization

to enhance organizational processes. This shift has

altered the competitive landscape by prioritizing

interaction and information as central to business

operations (Stone et al., 2017; Park, 2018).

The platform economy offers companies new

ways to create and transfer (Koponen 2019) value by

monetizing data and the added value it generates.

Information is a primary value stream in the network,

with material and financial flows relying on real-time

information to function efficiently (Herrala &

Pakkala, 2009). Service platforms, such as websites

and social media, streamline communication and

partnerships by facilitating timely information

exchange between companies (Kothandaraman &

Wilson, 2001; Herrala & Pakkala, 2009).

For micro-enterprises aiming to expand their

reach and engage audiences, digital platforms—

particularly social media platforms such as Facebook

and Twitter—offer accessible and effective options

(Ohlsbom et al., 2024). Studies show that small

businesses with fewer than 50 employees rely heavily

on social networking platforms like Facebook and

Twitter, with over 80% utilizing them (Webb &

Roberts, 2016). Social media enhances value creation

through its capacity for data collection, customer

interaction, and reputation management. Companies

can use social media to engage in sales, communicate

with customers, and develop relationships that may

lead to new business opportunities. (Drummond et al.,

2023)

In addition to advertising, social media is also an

effective platform for e-commerce. E-commerce

refers to the sale of products and services over the

internet and enables businesses to redefine their value

proposition, develop customer relationships and

improve operational efficiency. Using social media as

a platform for e-commerce enables companies to

reach a wider customer base, lower costs, continuous

sales, better supply chain management, more efficient

analysis of customer data, a more dynamic pricing

strategy and the possibility of innovative business

models and partnerships. (Kothandaraman & Wilson

2001)

Despite these advantages, micro-enterprises face

significant challenges in using digital platforms

effectively. Key issues include platform instability,

targeting difficulties, and intense competition

(Thrassou et al., 2020). Constant changes to platform

features can make it challenging for small companies

with limited resources to keep up. Additionally,

accurately targeting consumers requires a deep

understanding of the audience, which micro-

enterprises may lack due to limited resources and data

access. Finally, competition on service platforms is

intense, making it difficult for smaller players to

differentiate themselves. (Zeng et al., 2010)

2.3 The Non-Timber Forest Product

Sector

The non-timber forest products (NTFP) sector

encompasses activities related to natural products

such as wild berries, mushrooms, and other unique

forest products such as sap (Wacklin, 2021). The

Finnish definition of non-timber forest products

(NTFPs) differs from that in other countries; for

instance, some definitions exclude materials derived

from trees as NTFPs (Penn & James, 2008), while

others include game and fish as part of NTFPs

(Stanziani, 2008). The sector includes various

activities, from the harvesting of raw materials to

their processing, trade, and use in tourism and

wellness services (Wacklin 2021). In 2020,

approximately 770 companies were operating within

Finland's non-timber forest products sector. Of these,

72% were micro-enterprises with fewer than 10

employees, 23% were small enterprises, and only 5%

were medium or large enterprises with over 50

employees (Wacklin 2021).

The natural products sector's value chains remain

somewhat underdeveloped, creating challenges in

defining a comprehensive value network. This

underdevelopment is largely due to limited resources

for research and development (Wacklin 2022).

Despite this, several key aspects of customer value

have been identified within the sector. Customer

value in the natural products sector is based on

product sustainability, health benefits, and quality.

Consumers particularly value the purity, quality, and

domestic origin of natural products. Interest in

sustainability has grown in recent years as public

awareness of environmental and biodiversity

concerns has increased (Wacklin 2022).

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

204

3 RESEARCH DESIGN

This study follows a qualitative case study approach,

integrating various theories to form a synthesized

framework (Vilkka, 2023). The primary theories of

value networks and value creation are applied within

the context of the Finnish non-timber forest products

(NTFP) sector. The theoretical foundation was

developed through a comprehensive literature review,

which included both academic literature and annual

reports from the NTFP sector. This review prioritized

recent, relevant publications, along with industry-

specific standards and regulatory publications. The

inclusion of annual reports provided up-to-date

quantitative data and insights specific to the NTFP

sector.

Data collection was conducted through semi-

structured thematic interviews to ensure consistency

across interviews, covering core themes and

questions (Saunders et al., 2016). Interviews were

conducted with seven NTFP operators and one expert

to gain insights into sector dynamics, value creation

in micro-enterprises, and the role of digital platforms

in value generation. Selected companies represented

diverse roles in the supply chain—production, sales,

and processing—and were chosen using information-

oriented sampling (Flyvbjerg, 2011). Interviewed

companies also had extensive experience with natural

products.

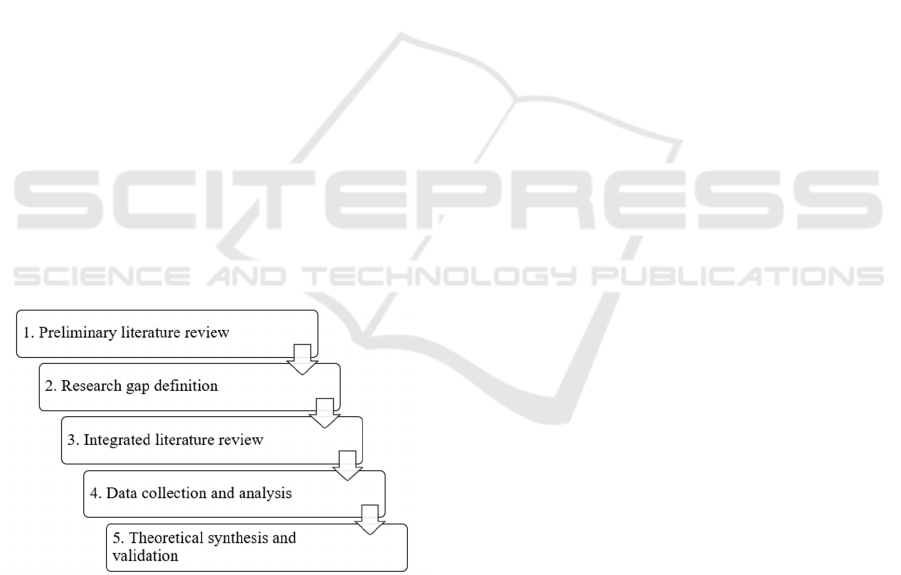

The research process consisted of the five stages

illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Research Process.

The process began with a preliminary literature

review to analyse prior research on value networks,

digital platforms, and micro-enterprises, followed by

the identification of a research gap. After establishing

the research gap, a deeper literature review was

conducted to build a theoretical foundation.

A pilot interview preceded the main data

collection to refine the thematic interview guide (Yin,

2003). The guide for operator interviews was

organized around three themes:

1. Operator Background and NTFP Usage:

Basic information about the business and products

used.

2. Value Creation: How the operator

generates value for customers.

3. Digital platform Use in Value Creation:

Operator's use of digital service platforms and how it

supports value creation.

The interviews with the expert followed similar

themes but took a more general approach, focusing on

value creation and digital platform use from a micro-

enterprise perspective. The expert, though not a

professional in NTFP, provided insights on platform

exploitation and value creation strategies.

The interviews lasted approximately 25-40

minutes each, were recorded with permission, and

subsequently transcribed. A thematic analysis was

then conducted following Naeem et al. (2023),

providing insights that align with the study's

objectives.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Defining the Value Network

Through the interviews, it was possible to identify the

different actors involved in the networks of

companies. However, the interviewed companies

operated with different business models and at

different stages of the value network which means

that not all of them have the same network members

and relationships with regards to the network

member.

The interviews revealed that operators in the non-

timber forest product sector have very different

relationships with different types of actors. As a

result, the value networks in the sector can vary

greatly and it was therefore useful to draw up two

different value networks for the non-timber forest

products sector according to whether the companies

used retailers to sell their products or whether they

sold their products by themselves. The first value

network (see Figure 2) describes the network of

actors most frequently encountered in the interviews,

i.e. the companies that sell themselves. The second,

wider value network (see Figure 3) describes the

network of actors who use retailers to sell their

products.

Digital Platform-Based Value Creation in Micro-Enterprise Networks

205

Figure 2: Narrow Value Network.

Figure 3. Wide Value Network.

Most of the companies interviewed had no

relations with other actors and ran their business

entirely on their own. The collection of the raw

material was handled by entrepreneurs themselves;

they were sold unprocessed or processed by the

entrepreneurs themselves, again without any member

of the network. As a rule, the entrepreneurs sold their

products themselves, which meant that there were no

operators involved in resale or distribution. However,

all the businesses interviewed did use some type of a

digital platform. Although the level of digital

platform usage varied greatly from one company to

another, the value network of each company

interviewed also included a service provider. Most of

the companies interviewed also had some form of

competitive relationship, which is why the value

network also includes competitors.

The value generated by the actors in a network of

non-timber forest product companies varies greatly

from one actor to another. Some actors provide only

physical products to the main actor of the network,

some only information and some actors do both. The

physical products vary from raw materials to finished

product and are passed around in the value chain

slightly differently according to the interviewees. In

the narrower value networks, where no suppliers or

distributors are used, the products pass exclusively

from the main company to the final customer. The

main company collects its natural products itself, so

that no raw materials are sourced from material

producers. In wider value networks, the raw materials

and the finished products move between the main

company, the material producers, the distributors, the

manufacturer and the final customer. Some of the

companies interviewed sold their products both

directly and through retailers. Information about

products also circulates between different actors.

The identified information that flows between the

interviewed companies and the different actors was

market information, competitive information,

strategic information, product information and

customer information. In the narrower value network,

market information flows only between the website

provider and the main company, and in a wider

network, market information can also be obtained

from retailers. In both networks, strategic and

competitive information flows between competitors

and the main company. Product information also

flows between the website provider, competitors and

the main company in both networks. In both

networks, customer information is provided by the

end customer. The platforms used by the interviewed

companies also provided a sales and ordering

channel.

The website provider allows the interviewed

companies to access the sales and ordering channel.

The sales and ordering channels allow the main

company to get closer to its customers, which are

easier to reach using digital platforms. These

channels are present in both value networks and in

addition, orders are also received directly from

customers.

Based on the interviews, collaboration between

the various actors in the value network is limited. The

interviewees did not mention any research or

development being a part of their network activities.

The collaboration between the members in the value

network consists of information sharing and some

members also resale their products together. Some of

the actors in the field did not have any relationships

with other members in the value network. Those who

had felt like that information flows freely between

different parties, and that the relationships with other

members are close. Information sharing happens

mainly digitally, but also face to face.

The interviews revealed that the key values for

customers include sustainability, quality and purity of

the products. The customers are also keen on knowing

the origin of the products they are buying. The

companies interviewed didn’t have a particularly

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

206

strong brand image. There were no attempts made to

create communal activities with the customers and

that customers were not an active part of the R&D

processes. Customer feedback collection was not

facilitated even though the interviewees felt it was an

important part of operating the business.

4.2 Value Creation Using Digital

Platforms

The interviews explored the types of platforms that

companies use in their business. The assumption was

that companies would use several social media

platforms, as well as platforms familiar to the Finnish

non-timber forest product sector such as Kerääjä.fi,

which is a digital platform where companies and

collectors can meet each other (Kerääjä.fi, 2024).

When asked about digital platforms, companies

initially identified only social media platforms in their

own operations, but when asked more specific

questions, they also found platforms related to

internal operations. Companies had relatively few

service platforms in use, the most popular of which

was Facebook. In addition, many had their own

websites and some communication platforms. The

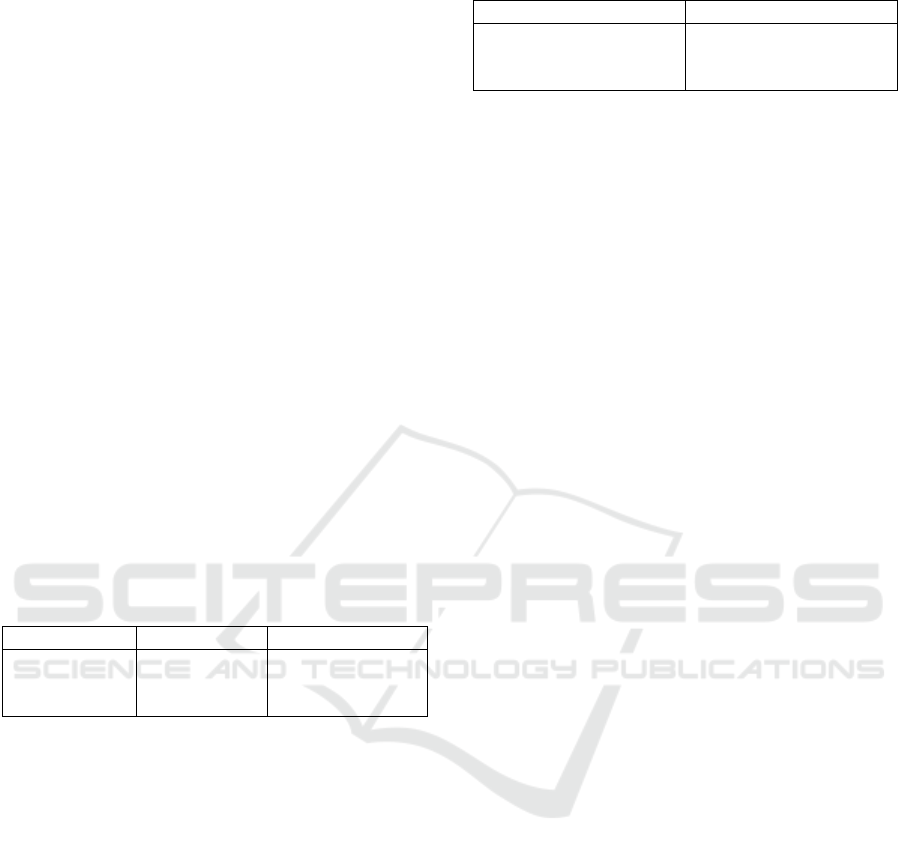

platforms used are presented in Table 2.

Table 2: Digital Platforms Used.

Webpa

g

es Social media Communication

Company

webpages

Kerää

j

ä.fi

Faceboo

k

Instagram

E-mail

WhatsApp

After mapping the digital platforms, the

interviews focused on the value-creating activities for

which the platforms were used. Companies used

platforms for both internal and external activities, but

there were significantly more external activities than

internal ones. The external activities for which

companies used platforms were marketing, REKO

rings and sales. REKO circles, also known as "rings",

offer consumers the opportunity to buy food produced

and prepared in close proximity directly from the

primary producer or manufacturer. The producer

presents their range in a closed Facebook group,

through which the consumer orders the products they

want. The exchange takes place at a time and place

agreed in advance by the district. (Aitomaaseutu.fi,

2024) The only internal activity identified was

communication with customers and other actors.

Table 3: External and Internal Activities.

External activities Internal activities

Marketing

REKO

Sales

Communication

Companies felt that the digital platforms helped

them to increase sales and better serve their customers

and that digital platforms are cost efficient and can be

widely used on business purposes. Marketing was the

most used activity by the interviewed companies on

the digital platforms and the main marketing activity

of the companies was to distribute company related

news. For example, the companies shared

information about their opening hours, new products

and participation in events. The interviewed

companies mainly marketed on Facebook, but also on

Instagram.

A few interviewees mentioned that they do not

spend any money on marketing. There was interest in

using digital platforms for marketing, but here again,

the situation was encountered that companies do not

have the time or resources to invest more in marketing

and that companies are currently selling at a sufficient

level. The companies interviewed did not consider

marketing to be a terribly important part of their

business, and did not seem to have any kind of

marketing plan, but instead took a relaxed approach

to it.

The only internal activities for which the

interviewed companies used digital platforms was

communication. Communication was done with

customers and other actors, and the interviews

revealed that many interviewees preferred to use e-

mail or phone calls to communicate with customers.

The interviews highlighted two different groups

of customers who have very different attitudes

towards the use of business platforms. These

customer groups were older and younger customers.

Based on the interviews, the older customers did not

seem to mind whether a company uses digital

platforms or not. This contrasts with younger

customers, who tend to measure a company's

credibility based on its presence and engagement on

digital platforms.

Although the interviews mainly highlighted the

opportunities for businesses created by the digital

platforms, the companies interviewed also identified

challenges. They felt that the digital platforms were

of some benefit to their business but could not really

identify any tangible benefits of using them. While

there are many different opportunities for digital

platforms, there is fierce competition for customers

and how to reach them, which poses challenges for

Digital Platform-Based Value Creation in Micro-Enterprise Networks

207

some of the companies interviewed. The main

challenges faced by the companies interviewed in

creating value were limited resources, coupled with a

lack of skills and a reluctance to develop. One of the

companies interviewed mentioned as a pre-cursor that

they do not have enough resources and as a result they

have not made any mark-to-market sales recently.

5 DISCUSSION

The companies surveyed had few network activities,

which means that the value networks do not include

many different actors. For micro-enterprises,

networking and being part of a network is important

for doing business. In small businesses, lack of

resources is a major challenge for business

development and, in some situations, for enabling

business (Konsti-Laakso et al. 2012), which is why

networking and building relationships is also

important for the business of small non-timber forest

product companies. The companies interviewed also

lacked resources and skills to further develop their

business through digital platforms which is a similar

finding with the research made by Zeng et al. (2010).

Micro-enterprises should focus on their

customers. Earlier, it emerged that the interviewees

are interested in customer feedback, but they do not

collect it in any way. They do not in any other way

map out the customer's wishes or needs. The idea of

value networking is to create value for the customer,

and therefore it is good to know what customers want

from digital platforms and which things create value

for them (Bovet & Martha, 2020). Collaboration in

the value network in turn leads to higher value

creation for the customer (Nielsen, 1988; Madhavan

et al., 1998).

To effectively communicate to customers and to

build up customer base, the easiest way is to use

digital platforms so that information can be

distributed to the widest audience possible (Ohlsbom

et al., 2024). The effective use of digital platforms

such as social media together with the customers of

the non-timber forest product sector could therefore

have the potential to create both customer value and

satisfaction. The usage of digital platforms could also

be utilized to collect customer feedback, an activity

which was seemingly lacking in the companies

interviewed.

The main activity that digital platforms were

utilized in the companies interviewed was marketing,

but this wasn’t seen as such an important activity. As

learning marketing is seen as one of the most

important needs for micro-enterprises (Kuismanen et

al. 2019) it would likely be beneficial for the

companies in the non-timber forest product sector to

create solid marketing strategies and to learn

marketing skills.

Finally, it’s important to note that business owners

do have different motivations for running their

business. For some, it isn’t done out of the need for

monetary funds, but out of the pure joy of providing

fresh produce to local communities. If everything

gathered is sold and the owner of the business is

happy with the result, it doesn’t force the owner to

allocate resources to boost the sales even more. This

is especially true if the new activity requires the

owner to sacrifice their time and perhaps money to

learn a new skill which might seem trivial to them.

6 CONCLUSION

This study aimed to explore the relevance of

cooperation with stakeholders for micro-enterprises.

As the most important needs for business

development learning marketing and sales and

networking were identified. Micro-enterprises

suffered from lack of expertise, resources and

innovation capacity, which were a major constraint to

innovation and business development. For micro-

enterprises the most efficient way to grow their

customer base and marketing audience is to apply

digital platforms. In doing this, the social media

platforms have also gained popularity. However,

micro-enterprises face various challenges in

leveraging the use of digital platforms in their

business including the constant changes in digital

platforms, targeting consumers and competition in the

markets. The digital platforms used by the companies

interviewed included various websites, social media

platforms and communication platforms. The most

popular of these platforms were Facebook and email.

The companies did not use websites for non-timber

forest products operators. The use of different digital

platforms was very limited some organizations do not

utilize any digital platforms.

This study provides a limited perspective due to

its case-study approach. Future studies should explore

ways to develop micro-enterprise networks to support

collaboration and to find ways to tackle the issues

micro-enterprises have with digital platforms.

REFERENCES

Aitomaaseutu.fi. (2024). REKO-lähiruokapiirit.

[Webpage]. [Referenced 29.10.2024]. Available:

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

208

https://www.aitomaaseutu.fi/lahiruokaa/keski-suomen-

rekolahiruokapiirit#:~:text=REKO%20on%20l%C3%

A4hiruoan%20myynti%2D%20ja,elintarvikkeita%20s

uoraan%20alkutuottajalta%20tai%20%2Dvalmistajalt

a.

Allee, V. (2008). Value network analysis and value

conversion of tangible and intangible as-sets. Journal of

Intellectual Capital. Vol. 9. No. 1. s. 5-24.

Bovet, D. & Martha, J. (2000). Value Nets: reinventing the

rusty supply chain for competitive advantage. Strategy

& Leadership, 28.4.2000. s. 21-26.

Drummond, C., McGrath, H. & O’Toole, T. (2023).

Beyond the platform: Social media as a multi-faceted

resource in value creation for entrepreneurial firms in a

collaborative network. Vol. 158.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2011). Case study. The Sage Handbook of

Qualitative Research, 4, 301–316.

Herrala, M. & Pakkala, P. (2009). Value-creating networks

– A conceptual model and analysis. [Report].

[Referenced 26.2.2024] Available:

https://institute.eib.org/wp-con-

tent/uploads/2016/04/Final_Report_2009_Value-

creating_networks_-_a_conceptual_mo-

del_and_analysis.pdf

Kerääjä.fi. (2024). Front page. [Webpage]. [Referenced

29.10.2024]. Available: https://www.keraaja.fi

Konsti-Laakso, S., Pihkala, T. & Kraus, S. (2012).

Facilitating SME Innovation Capability through

Business Networking. Creativity and innovation

management. Vol. 21. s. 93–105.

Koponen, J. (2019). Alustatalous ja uudet

liiketoimintamallit: Kuinka muodonmuutos tehdään.

Alma Talent. Helsinki

Kothandaraman, P. & Wilson, D. (2001). The Future of

Competition – Value Creating Networks: Industrial

Marketing Management. Vol. 30. s. 379–389.

Kuismanen, M., Malinen, P. & Seppänen, S. (2019).

Yksinyrittäjäbarometri syksy 2019. Suomen yrittäjät.

Madhavan, R., Koka, B. & Prescott, J. (1998). Network in

transition: How industry events (re) shape interfirm

relationships. Strategic Management Journal. Vol. 19.

No. 5. s. 439–459.

Naeem, M., Ozuem, W., Howell, K., & Ranfagni, S. (2023).

A Step-by-Step Process of Thematic Analysis to

Develop a Conceptual Model in Qualitative Research.

International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 22.

https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069231205789

Nielsen, R. (1988). Cooperative Strategy. Strategic

Management Journal. Vol. 9. No. 5. s. 475-492.

Ohlsbom, R., Malinen, P. & Nyroos, M. (2024). PK-

yritysbarometri kevät 2024. Suomen yrittäjät.

Park, J. (2018). Business Architecture Strategy and

Platform-Based Ecosystems. Springer Singapore. Web.

Penn, J. & James, W. (2008). Non-Timber Forest Products

in Peruvian Amazonia: Changing Patterns of Economic

Exploitation. The American Geographical Society’s

focus on geogra-phy. Vol. 51. s. 18-25.

Peppard, J. & Rylander, A. (2006). From Value Chain to

Value Network. European Management Journal. Vol.

24. s. 128-141.

Rashidirad, M. & Salimian, H. (2020). SME's dynamic

capabilities and value creation: the mediating role of

competitive strategy. Vol. 32. No. 4. s. 591-613.

Saunders, M., Lewis, P. and Thornhill, A. (2016). Research

Methods for Business Students. 7th Edition, Pearson,

Harlow.

Stanziani, A. (2008). Defining “natural product” between

public health and business, 17th to 21st centuries. Vol.

51. s. 15-17.

Stone, M., Aravopoulou, E., Gerardi, G., Todeva, E.,

Weinzierl, L., Laughlin, P. & Stott, R. (2017). How

Platforms Are Transforming Customer Information

Management. The Bottom line (New York). Vol. 30. s.

216–235

Thrassou, A., Uzunboylu, N., Vrontis, D. & Christofi, M.

(2020). Digitalization of SMEs: A review of

Opportunities and Challenges. The Changing Role of

SMEs in Global Business. s. 179-200.

Viitanen, J., Paajanen, R., Loikkanen, V. & Koivistoinen,

A. (2017). Digitaalisen alustatalouden tiekartasto. Työ-

ja elinkeinoministeriö. [WWW-document].

[Referenced 9.5.2024] Available:

https://www.businessfinland.fi/globalassets/julkaisut/a

lustatalouden_tiekar-tasto_web_x.pdf

Vilkka, H. (2023). Kirjallisuuskatsaus metodina,

opinnäytetyön osana ja tekstilajina. Helsinki: Art

House. Print.

Wacklin, S. (2021). Tulevaisuuden luonnontuoteala. TEM

toimialaraportit 2021:6. [WWW-document].

[Referenced 20.2.2024] Available:

https://julkaisut.valtioneu-

vosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/163669/TEM_2021_6

.pdf

Wacklin, S. (2022). Arvoketjuja vahvistamalla volyymia

luonnontuotealalle. TEM toimialaraportit 2022:5.

[WWW-document]. [Referenced 21.2.2024] Available:

https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/handle/10024/16443

3

Webb, S. & Roberts, S. (2016). Communication and Social

Media Approaches in Small Businesses. Journal of

marketing development and competitiveness. Vol. 10.

s. 66.

Wincent, J. (2005). Does Size Matter? A Study of Firm

Behavior and Outcomes in Strategic SME Networks.

Journal of small business and enterprise development.

Vol. 12. s. 437-453.

Yin, R. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods.

Third edition. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage

Publications.

Zeng, S., Xie, X. & Tam, C. (2010). Relationship between

Cooperation Networks and Innovation Performance of

SMEs. Technovation. Vol. 30. s. 181-194.

Zhao, L. & Aram, J. (1995). Networking and Growth of

Young Technology-Intensive Ventures in China.

Journal of business venturing. Vol. 10. s. 349–370.

Digital Platform-Based Value Creation in Micro-Enterprise Networks

209