Evaluating the Impact on Usability and Acceptance of ECAs in

m-Health Applications for Older Adults

Raquel Lacuesta Gilaberte

1a

, Eva Cerezo Bagdasari

2b

and Javier Navarro-Alamán

3c

1

Department of Computer Science and Engineering of Systems, I3A (Institute of Engineering Research of Aragon),

EUPT/Universidad de Zaragoza, Spain

2

Department of Computer Science and Engineering of Systems, I3A (Institute of Engineering Research of Aragon),

EINA/Universidad de Zaragoza, Spain

3

Department of Computer Science and Engineering of Systems, EUPT/Universidad de Zaragoza, Spain

Keywords: ECAs, Avatars, m-Health, Older Adults.

Abstract: In the context of m-health applications, developing user-friendly interfaces to improve usability and

acceptance by older adults has become a prominent research topic. The use of embodied conversational agents

(ECAs) seems promising as they allow interacting through natural verbal and nonverbal communication.

However, analyses about the design and acceptance of embodied conversational agents embedded in m-health

applications for older adults are needed. In this paper, we present a study carried out to analyse the usability

and acceptance of ECAs interfaces in m-health applications, compared to traditional tactile text interfaces.

The study carried out has involved 23 users over 65 years old with promising results. The ECA interface was

positively assessed and its acceptance increased compared to the traditional one, but although the feelings

arisen are positive, users still claim for less complexity and a more careful design.

1 INTRODUCTION

Digital tools in clinical practice mean new tools for

clinicians to deliver care. One is the ability to collect

and store information about an individual's condition

and care delivery through interoperable online

systems. These systems may also be the only way to

approach older adults in isolated situations such as the

one caused by the COVID pandemic.

Within the technology field, there are different

approaches for monitoring older adults. This

monitoring can be done through different

methodologies such as surveys, interviews, forms,

tests… However, new methods are currently being

developed through technology, such as chatbots,

virtual assistants, or conversational agents. The use of

a chatbot could be complex if the older person cannot

read the screen because of problems (physical or

cognitive) related to age or the existence of illiterate

people who cannot write or read but can speak.

Virtual assistants allow appointments, messages to be

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4773-4904

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4424-0770

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3843-6796

sent, and calls to be made by voice, but they are not

designed to monitor people but rather to facilitate

specific tasks without the need to write.

ECAs (Embodied Conversational Agents) refer to

computer generated life-like characters that interact

with human users in face-to-face conversation

(Cassell & Bickmore, 2000). They can emulate some

human characteristics, using different types of

interactions such as speech, gaze, hand gestures, and

other nonverbal modalities (Wargnier et al., 2015).

This type of interaction, called multimodal communi-

cation, is of great utility in healthcare by providing

potential personal interfaces to interact with users in

healthcare settings (Turunen et al., 2011).

Conversational agents using dialogues will therefore

be a way to collect follow-up data from users.

However, it is worth noting the arousal of conflicts

when older adults use of technology, mainly due to

the digital exclusion they suffer. Digital exclusion

causes them different fears because it is unknown to

them, and they may even feel ashamed of not

Gilaberte, R. L., Bagdasari, E. C. and Navarro-Alamán, J.

Evaluating the Impact on Usability and Acceptance of ECAs in m-Health Applications for Older Adults.

DOI: 10.5220/0013216600003938

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2025), pages 35-45

ISBN: 978-989-758-743-6; ISSN: 2184-4984

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

35

knowing how to use it and may be hesitant to ask for

help (Nowakowska-Grunt et al., 2021). In addition,

there is another major issue, which is trust. Many

older people do not want to interact with

conversational agents because they do not have

confidence in them as they do not know what they can

understand. Embodied agents may make the elderly

feel more comfortable avoiding the feeling of talking

to "a machine". The challenge is to design them so

that they best suit the target users and enable seamless

interaction.

This paper focuses on the analysis of the use of

interfaces based on ECAs in m-health applications to

be used by older adults. In these environments, the

data collection process is especially critical: a proper

m-health app design and the use of well-designed

ECAs that generates acceptation may drive to a more

natural and accepted data entry. The aim of the study

carried out is to know if this kind of interfaces will

increase usability and acceptance of the apps,

compared to traditional ones.

The structure of the paper follows. First, in

section 2, we analyze the related work regarding

ECAs and their use in m-health applications. Then, in

section 3 we present an initial study carried out to

obtain information about the preferences of older

adults regarding ECAs design. In section 4 we present

the study done to compare an ECA-based interface

versus a tactile text interface, in the context of an m-

health app developed to retrieve information from

older adults in a day-to-day basis. In section 5 results

are presented, with special focus on the analysis of the

acceptance of the ECA interface. Section 6 is devoted

to conclusions.

2 RELATED WORK

In the scientific literature, numerous articles referring

to virtual agents focus on providing companionship to

older adults who suffer from social isolation and

loneliness, which harms both their physical and

mental health (Bérubé et al., 2021; Bravo et al., 2020;

Dai & Pan, 2021; Franco dos Reis Alves et al., 2021).

In these works an ECA provides companionship and

care by monitoring possible falls or assisting in

managing medication intake.

Other articles focus on the use of the conversa-

3tional agent to register symptoms. Tanaka et al.

(Tanaka et al.,2017), focuse on detecting dementia by

employing a computer avatar, which performs spoken

queries and examines the mental state. The

conclusions obtained are that in addition to being able

to diagnose accurately, there was a finding that allows

more precise detection and reduces effort and time for

this diagnostic process. This work (Pacheco-Lorenzo

et al., 2021) focuses on whether the use intelligent

conversational agents can be used for the detection of

neuropsychiatric disorders. The conclusion is that this

is an emerging and promising field of research with

comprehensive coverage. However, they were not

subject to robust psychometric validation processes,

so they lacked a more rigorous validity. The last

article (Bérubé et al., 2021), focuses on preventing

and treating chronic and mental health conditions

using conversational agents. The conclusion reached

is that it is at a very early stage of research, where its

validity cannot yet be fully determined. Nevertheless,

it can be said that the results are encouraging in the

absence of conclusive evidence.

The following articles focus specifically on the

importance of the agents' design and the preferences

of older people about them. The article (Shaked,

2017) emphasizes the importance of designing

interfaces easy to use, attractive and allowing a

smooth interaction, especially for the elderly.

Developing avatars for the elderly is a challenge: they

review key features to be taken into account that

include visual, performance and environmental

aspects. as well as trust and entetainment aspects to

design helpful and friendly interfaces for the elderly.

The work of Salman et al (Salman et al., 2021a)

focuses on the addition of empathy in conversational

agents. For this purpose, a qualitative analys33is of

empathic dialogues in actual calls between a doctor

and a patient was carried out. The conclusions

reached are that empathic dialog is affected by

gender, age, demographics, and even by medical

history. The article (Cheong et al., 2011) explores the

use of embodied agents as virtual representations of

the older adults. After conducting a study with 24

people over 55, they visualized more than 20 avatars,

they concluded that elderly participants were unable

to identify with them. Nevertheless, results showed a

strong trust on child characters and an attraction

towards animal and object avatars. The race the avatar

appeared to play a role, as well as other characteristics

as height, clothing, facial hair, skin tones, or even the

brightness of the eyes.

In the articles (Esposito et al., 2018, 2019), in

addition to focusing on the agents' design, also

studied the preferred technological device for people

over 65 years of age based on their experiences. The

vast majority share that this is the smartphone since it

is the one they find easiest to use. Regarding the

agent, in the article (Esposito et al., 2019), an

empathic virtual coach is developed to improve the

well-being of the elderly. The results showed that

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

36

older people tended to prefer the female gender and

were more inclined to engage with it. However, it is

worth noting that individuals with some experience in

technology were not motivated and even perceived

the agents as neither captivating, exciting, nor

attractive.

The article (Esposito et al., 2018) conducts a

study with older adults to validate artificial agents.

From a sample of 45 adults over 65 years of age and

in good health, four avatars were visualized, 2 of the

male gender and 2 of the female gender, with

different personality traits (angry, depressed, cheerful

and practical). After passing them a questionnaire, the

results were the preference for a female agent and a

positive, cheerful and practical personality, without

considering the voice issue because the videos are

played without sound. This article (Thaler et al.,

2020) emphasizes the importance of visual

appearance, as it influences the perception and

acceptance of conversational agents. However,

greater humanization of the characters does not

necessarily lead to better acceptance, as it often

triggers uneasiness and rejection among people. In

fact, increased human-likeness correlates with

heightened perceived discomfort. These results were

consistent across all participants, regardless of

gender, age, or sex. This article (Thaler et al., 2020)

emphasizes the importance of visual appearance, as it

influences the perception and acceptance of

conversational agents. However, greater

humanization of the characters does not necessarily

lead to better acceptance, as it often triggers

uneasiness and rejection among people. In fact,

increased human-likeness correlates with heightened

perceived discomfort. These results were consistent

across all participants, regardless of gender, age, or

sex.

As we may see there are several studies that point

to the potentiality of ECAs in m-health applications

as well as to the importance of their design, but no

clear design or usability recommendations are given.

Therefore, we decided to do an initial study to get

direct information about the preference of older adults

regarding the design of the ECAs.

3 INITIAL ECA STUDY

In order to select the ECAs to be used and to make a

first assessment of their acceptance, a first

exploratory study was carried out with older adults in

a nursing home,

3.1 Instruments, Method and

Participants

8 possible ECAs (see Figure 1) were generated

modifying sex (men/woman) and age (kid, adult,

older adult).

Figure 1: Pool of initial possible ECAs.

First, the users were shown all of them and they

had to select just one based only on their appearance.

For that agent, a video showing the agent was

presented to the user, who was afterwards asked to

rate the following aspects:

- Appearance

- Voice

- Social interaction:

o Naturalness

o How

comfortable/uncomfortable

would they feel if they had to

interact with him/her

o Confidence transmitted

o Credibility

o Emotion expressed by the agent

(Yes/No,

positive/negative/neutral).

All of the aspects had to be valued by using a

Likert scale (from 1 to 7) except the last one. To

facilitate the process no questionnaire was given to

the users: the information was collected just talking

with them In fact, we were not so interested in the

quantitative measurements but in knowing the

general preferences of the users as well as their

reasons.

Evaluating the Impact on Usability and Acceptance of ECAs in m-Health Applications for Older Adults

37

After completing the first agent assessment, the

user was asked to choose another agent (second

favorite) and the process was repeated.

16 users participated in the study, 5 men and 11

women. Regarding their age, there was one user aged

between 60 and 69 years, 7 between 70 to 79 years,

five from 80 to 89, and 3 from 90 to 99. In terms of

their use of technology, less than 15% of them

connected to the Internet (once a month at most), and

about 45%. of them used it to find out about their

loved ones through calls or messages (from one day a

week to once a month). Regarding their abilities, they

had the typical visual, auditory and motor, reduced

abilities due to their age (see Figure 2), but no special

physical or cognitive impairment, and they were all

able to interact with a tablet (the device used in the

study).

3.2 Results

In the first election, the clear favorite was the adult

man (AV4), followed by the adult woman (AV3) and

finally the elderly man (AV1). The other agents were

not chosen. In the second vote, the girl (AV6) gets the

best vote, and then there are three tied avatars: adult

man (AV4), boy (AV5) and adult man 2 (AV8) with

the same number of people who have chosen them.

After, the elderly (AV1) and the adult woman (AV3);

the elderly woman (AV2) and the adult woman 2

(AV8) were not selected in any of the cases. We want

to emphasize that, the second selection was affected

by the first: if an agent had been voted for the first

time, it could not be repeated and many times, it

influenced the second choice: "in the first case, I have

taken a man, now I select a woman".

It can be concluded that, male characters with

young appearance and soft features were the

favourites. In general, attention was paid mainly to

their (pleasant) physical appearance. These results are

not aligned with other studies that reflect preference

for female characters (Esposito et al 2018). This may

be attributed to the medical context of the videos

(medical) and a social-gender issue that may have led

the participants prefer a (masculine) doctor character.

A similar issue was encountered with the age: the fact

of labeling the avatars as "elderly" or "child": a user

who did pay attention to this label presented a

comment of the type: "a child cannot be my doctor”.

Therefore our results should be considered within the

m-health application context. Other more general

issue were found: some users said to choose the agent

according to the resemblance to known persons. And

considering the emotions generated, the agent that is

best valued physically and at a social interaction level

is the one that generates the most positive emotions

in users.

Besides the selection, additional interesting issues

were detected:

- When we informed users about the study,

most users expressed their reluctance to use

technology. "I don't know how to do it" was

the common comments before even starting

to do anything. This highlights the critical

point of acceptance when developing apps

for the elderly.

- While the videos of the agents were being

viewed, except for a couple of users, all of

them tried to interact with them (despite the

fact that it was just a video): when the agents

greeted them, the users answered them, and

when they wished them a good day, the users

thanked them for those words. This may

show positive disposition towards an ECA

based interface. Nevertheless, these

interactions did not prevent them to give

them bad scores in the social interaction

questions.

- Participants felt reluctance to say negative

things about the agents ("I would not like to

give it a bad score") which may point out to

some kind of empathy or emotional liaison,

although later in the question linked to the

emotions they said he/she did not convey any

emotion

After this initial study, we decided to continue

adding a multimodal interface based on a young male

ECA to an m-health application being developed.

4 ECA INTERFACE

ASSESSMENT

After the initial study, an ECA based interface was

added to an m-health application designed to monitor

frail elderly people (Navarro-Alamán et al., 2021).

The app is aimed at the elderly population and its

main objective is to monitor users through surveys

but contains also different physical exercises

proposals, games to exercise memory and nutrition

advices. The initial interface was a traditional tactile

one. We decided to carry out an evaluation to assess

the impact of the ECA interface. In particular, we

wanted to answer the question:

Does ECAs help to improve usability and

acceptance of m-health applications by older adults?

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

38

(a) (b) (c)

Figure 2: Sample screens of the application without ECA (a) numeric insertion screen and (b) text insertion screen and of the

application with the ECA interface (c).

To carry out the assessment we created two

versions of the app: one with a traditional tactile

interface (Appv1) and other with an ECA-based

interface (Appv2) focusing in the daily surveys to be

completed by the users. In the first one (see Figure 2),

the users read the questions and introduce the answers

in a tactile/textual way. In the second version the

ECA-based interface allows the user to listen to the

questions answer them orally (giving a number, an

option or an open text, depending on the question).

The user has a button to hear again the question, to

ask for help and to dictate the answer.

A questionnaire was designed to carry out the

assessment; it is dived into four sections: (0) User

characterization, (1) Usability and acceptance, (2)

Agent’s rating (3) Users' app preference. User

characterization questions are aimed to determine

gender, use of technology and possible (hearing,

visual, mobility) impairing. In Table 1 the rest of the

questions are shown.

The test was performed by 23 users all of them

over 65 years of age with a mean age of about 72

years, (std deviation of 3.82), 13 participants were

female and 10 male. Regarding impairing, the most

frequent problems were vision problems, which affect

78% of the respondents, followed by hearing

problems and finger mobility with 39% both. All

participants had a cell phone, but Tablet ownership

drops to less than half (ten respondents). All of them

used phones just for making calls. 65% use it for

messaging (WhatsApp), and only three of them also

use them to view news.

Every user interacted with both versions (half of

them in one order and the other half in the reverse

order). The sessions were performed at users

locations supported by one researcher. First of all the

user filled the characterization questions (0) Then,

he/she tested (filling a questionnaire) one of the apps

(Appv1/Appv2), answered some questions, test the

second version (Appv2/Appv1) and answered some

questions. Finally, the user answered the preference

questions (3) –see Table 2-.

5 ASSESSMENT RESULTS

We will discuss the results in terms of agent’s rating,

general usability and acceptance impact.

5.1 Agent’s Rating

The agent’s physical appearance received an average

rating of 6.5 out of 10, while its credibility was rated

at 6.8 out of 10. Regarding the emotions conveyed,

70% of users stated that the agent successfully

transmitted emotions, and 86% of them described

Evaluating the Impact on Usability and Acceptance of ECAs in m-Health Applications for Older Adults

39

Table 1: Assessment questionnaire.

Cate

g

or

y

Dimension Question T

yp

e

1. Usability/

acce

p

tance

Perceived ease of use Q1. The application is effortless to use Yes/No/Maybe?

Perceived ease of use Q2. I find this a

pp

lication unnecessaril

y

com

p

lex Yes/No/Ma

y

be?

Perceived ease of use Q3.I needed to learn a lot of thin

g

s before I was able to use this a

pp

Yes/No/Ma

y

be?

Perceived ease of use Q4. I think I would need help from a tech savvy person to be able to

use this a

pp

lication

Yes/No/Maybe?

Perceived ease of use Q5. I imagine that most people would learn how to use this

a

pp

lication

q

uickl

y

Yes/No/Maybe??

Attitude towards use Q6. I am satisfied with this application Yes/No/Maybe??

Intention of use Q7. I would like to use this app to report other aspects of my health

to m

y

docto

r

Yes/No/Maybe??

Intention of use Q8. I would recommend that other a

pp

s I use be similar to this one Yes/No/Ma

y

be??

Attitude towards use Q9. The a

pp

is fun or entertainin

g

to use Yes/No/Ma

y

be??

Attitude towards use Q10. I felt confident in using this app Yes/No/Maybe??

2. Agent’s

rating

Physical appearance Q11. Assess its appearance Likert (1 to 7).

1 being not at all appropriate and 7 very

a

pp

ro

p

riate.

Credibility Q12 How much credibility does the agent give you? Likert (1 to 7).

1 being not at all credible and 7 being

ver

y

credible.

Emotion expression Q13. Has the agent transmitted any emotion?

If

y

es, how was the emotion transmitted?

Yes/No

Positive, Neutral or Ne

g

ative

3. Users' app

preference

Easier to use Q14. Which application do you find easier to use? Agent/ No agent

Easier to understand Q15.With what a

pp

lication do

y

ou understand the

q

uestions better? A

g

ent/ No a

g

ent

Feel better in the

interaction

p

rocess

Q16.With which application did you feel better in the interaction? Agent/ No agent

Feel more comfortable Q17.With which application did you feel more comfortable when

interactin

g

?

Agent/ No agent

Table 2: Groups of users and structure of their assessment sessions.

Users Group Group Questions First App Group Questions Second App Group Questions Group Questions

Group1 0 Appv1 1 Appv2 1,2 3

Group2 0 Appv2 1,2 Appv1 1 3

these emotions as positive or neutral. Overall, the

agents received a fairly positive evaluation, although

their physical characteristics could clearly be

improved with more time dedicated to their

development.

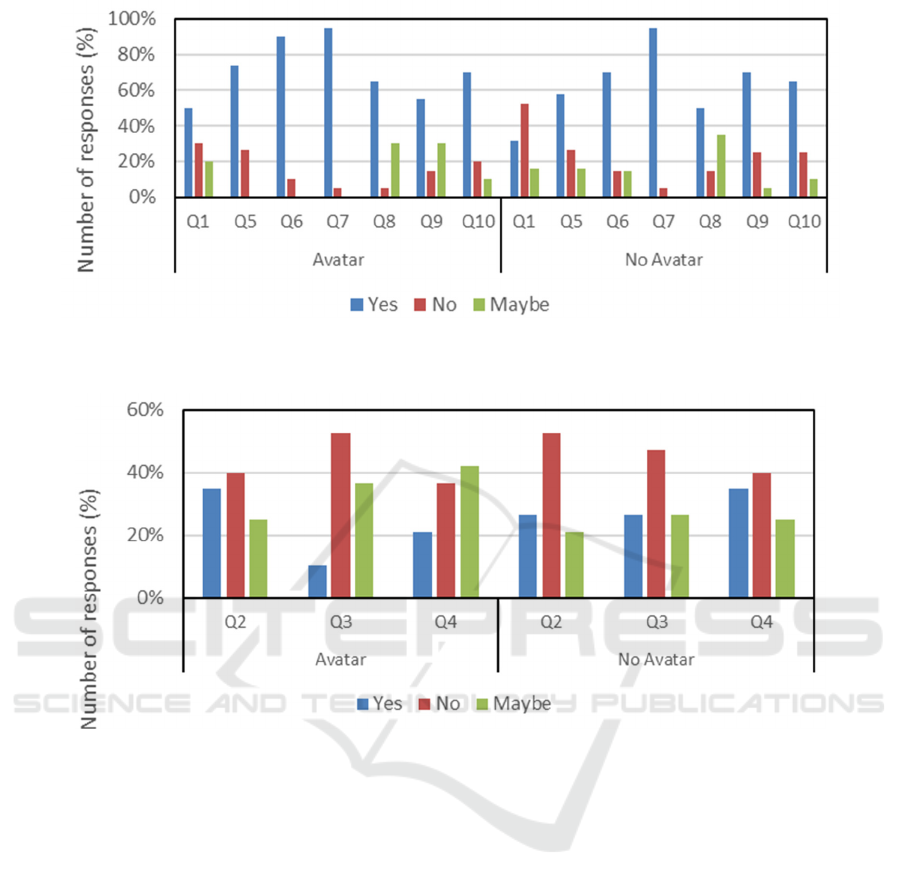

5.2 General Usability Analysis

We have divided, for a first general usability analysis,

the questions into two groups: those related to

positive aspects (Q1, Q5 to Q10) and those related to

negative ones (Q2, Q3, Q4).

Beginning with the questions on positive aspects

(see Figure 3), in all of them the application with ECA

is rated higher, both in those related to ease of

learning (Q1, Q5) and satisfaction with the

application (Q6, Q8, 10). In Q7. (“I would like to use

this app to report other aspects of my health to my

doctor”) the result with and without ECA is similar

and very positive (95%) which shows the very

positive overall rating of the app and its usefulness.

Only in Q9 (“The app is fun or entertaining to use”)

does it go from 70% (no ECA) to 55% (ECA). This

result may be connected with the perceived

complexity of the ECA version shown, as we will see

in the results of question Q2.

As for the negative questions, (Figure 4) although

in question Q2 ECA results are worse than non-ECA

ones, in Q3 and Q4, the results are better, i.e. although

users find the application with ECA complex they do

not think they would need to learn a lot of things or

get help to use it. This aspect is analyzed with more

detail in the next section when considering

acceptance.

5.3 Acceptance Analysis

In older adults, technology acceptance is a key

factor to be considered. This is why we were

interested in comparing the acceptance of both

interfaces. The Technology Acceptance Model

(TAM) is a commonly utilized paradigm for

understanding and predicting technology uptake.

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

40

Figure 3: Responses (Avatar/ECA, No avatar/ECA)to usability positive questions (greater affirmative percentage, better

result). Questions shown in Table 1.

Figure 4: Responses (Avatar/ECA, No avatar/ECA) to usability negative questions (lower affirmative percentage, better

result).

TAM was developed in the 1980s by Fred Davis

(Davis, 1989) and has since become a prominent

conceptual framework in the field of technological

adoption research. TAM focuses on four dimensions:

perceived utility, perceived ease of use, perceived

attitude towards use, and perceived intent to use. As

the aim of the evaluation was to compare both

interfaces (without and with ECA) we have focused

on three of them: perceived ease of use, attitude

towards use and intention to use, grouping the

questions (Q1 to Q10) around those three dimensions

for the acceptance comparative analysis.

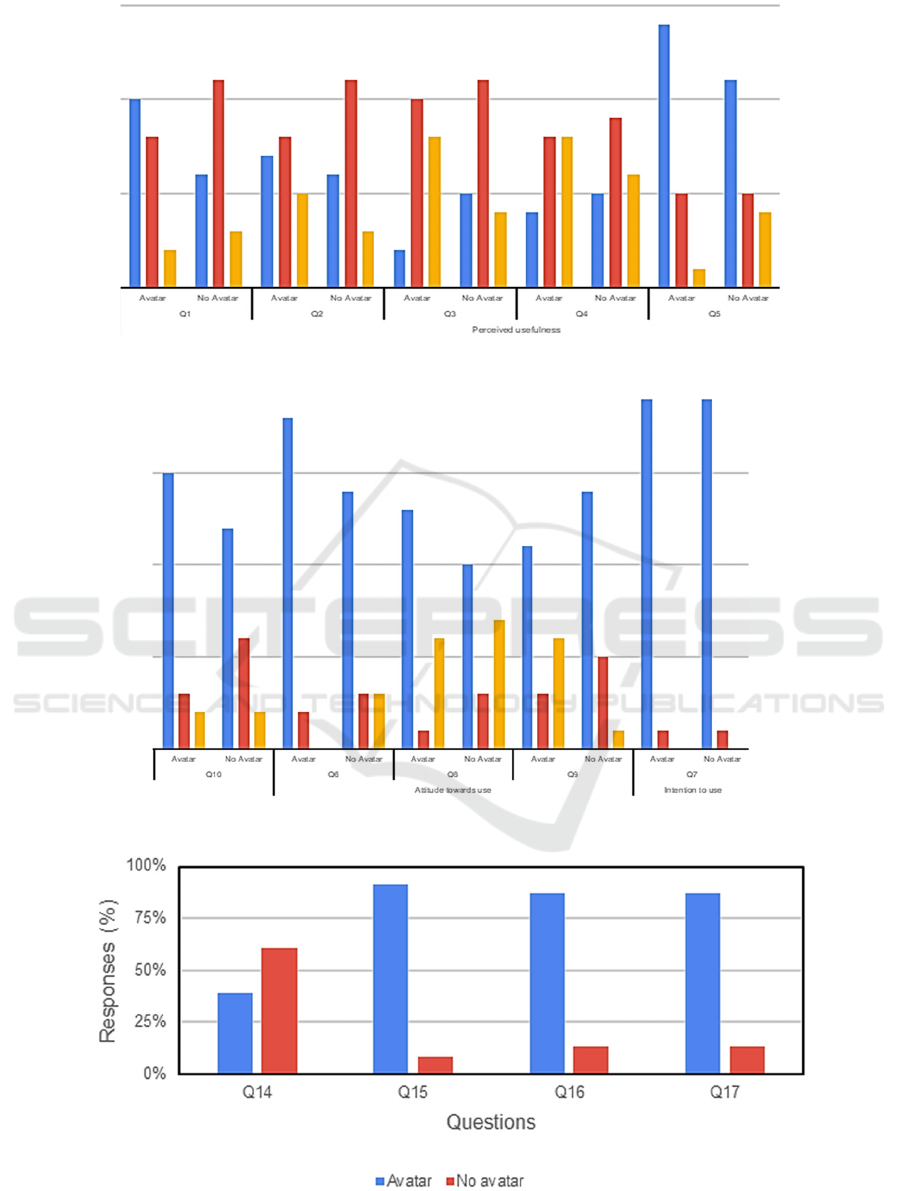

Perceived Ease of Use: This element is related to the

perceived ease of use of the application (see Figure

5). The questions Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4 and Q5 delve into

various relayed aspects.

Question Q1, "Using the application is effortless,"

highlights the importance of usability in the user

experience. An application that is perceived as easy

to use may generate a more positive and engaging

experience for users. On the other hand, an

application that is perceived as requiring effort can

generate frustration and affect overall user

satisfaction. About 50% of users with an ECA and

30% of users without an ECA responded

affirmatively, indicating that they perceive that using

the application does not require effort. Fifty-five

percent of users without an ECA responded

negatively, indicating that they find using the

application requires effort.

Question Q2, "I find this application

unnecessarily complex," highlights the importance of

simplicity in application design and functionality. An

app that is considered unnecessarily complex can be

confusing and discourage users from adoption and

continued use. As commented before, about 35% of

users with ECA and 30% of users without ECA

Evaluating the Impact on Usability and Acceptance of ECAs in m-Health Applications for Older Adults

41

responded affirmatively, indicating that they find the

application unnecessarily complex. Fifty-five percent

of users without an ECA responded negatively, while

only 40% of users with an ECA did so. We think that

this result is due to the need in the ECA version to

press buttons to hear the content and also to introduce

the voice answers, what was found difficult by the

Question Q3, "I needed to learn a lot of things before

I was able to use this application," provides us with

information about the participants' perception of the

learning curve required to use the application. Only

10% of users with an ECA and 25% of users without

an ECA responded affirmatively, indicating that they

perceived that they needed to learn many things

before being able to use the application. On the other

hand, 50% of users with ECA and 55% of users

without ECA responded negatively, indicating that

they did not have that perception.

Question Q4, "I think I would need help from a

person with technical knowledge to be able to use this

application," provides us with information about the

participants' perception of the need for technical

assistance to use the application. Only 20% of users

with an ECA and 25% of users without an ECA

responded affirmatively. Forty-five percent of users

without an ECA responded negatively, while 40% of

users with an ECA responded negatively.

Question Q5, "I imagine most people would learn

to use this application quickly," highlights the

importance of an application being intuitive and easy

to learn for most users. Participants who used the

application with ECA, 70 %, considered it easy to use

compared to those, 55%, who used the application

without ECA. As for the "No" response, there was an

equal proportion of 25% in both groups. However,

there was a notable difference in the "Maybe"

response, with only 5% of participants who used the

app with ECA showing doubts about the perceived

ease of use, compared to 20% of those who used the

app without ECA.

Summarizing, although the percentage of users

that found the application complex was a little higher

in the ECA case (35% compared to 30% in the non-

ECA interface) only 10% of users thought they would

have to learn a lot of things before using it (compared

to 25% in the tactile version), only 20% (compared to

25%) stated the think they would need help to use it

and 70% (compared to 55%) thought most people

would learn to use it quickly.

Attitude Towards Use: This element is related to

participants' attitudes toward application use (see

Figure 6). The questions Q6, Q8, Q9 and Q10 delve

into various aspects of it.

The question Q6, "I'm satisfied with this

application," highlights the significance of the user's

satisfaction as a key indicator of the application's

quality. The majority of users, both those with ECAs

and those without, demonstrated their satisfaction

with the application. 70% of users without ECAs and

90% of ECA users said "yes" to the question.

The question Q8, "Recommend that other

applications I use be comparable to this one,"

emphasizes the significance of the application's

perceived satisfaction and utility. Over half of users

without ECAs (50%) and the majority of ECA-using

users (65%) answered "yes." Although both groups

shown a willingness to recommend similar

applications, users without ECAs displayed a slightly

higher proportion of negative responses (15%)

compared to users with ECAs (5%).

The question Q9, "The application is fun or

entertaining to use," highlights the significance of

providing a user experience that is appealing in terms

of fun or entertainment. The majority of users, 55%

of those with ECAs and 70% of those without,

responded positively, indicating that they thought

using the application was fun or entertaining. The

usability problems commented before may explain

these differences.

Question Q10, "I felt confident in using this

application," highlights the importance of building

user confidence in using the application. A higher

percentage of participants who used the application

with ECA, 75%, felt confident in its use, compared to

60% of those who used the application without ECA.

In addition, a significant difference was observed in

the "No" response, with 15% of participants with

ECA indicating lack of confidence, in contrast to 30%

in the group without ECA. The "Maybe" response

was similar in both groups, with 10% of participants

selecting this option in both cases.

Intention to Use: This aspect refers to the

participants' intention to use the application (see

Figure 6).

The question Q7, "I would like to use this

application to inform my doctor about other aspects

of my health," is related to the use-intention factor. It

can be shown that in both cases, 95% of participants

indicated they intended to use the application to use it

in relation to their health's ongoing monitoring, while

only 5% indicated they did not want to do so.

As can be seen, the acceptance of the ECA

interfaces is higher (in the case of the perceived ease

of use an d attitude towards use dimensions) and

equal in the intention to use dimension.

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

42

Figure 5: Analysing perceived ease of use (Q1-Q5, Avatar/ECA, No avatar/ECA). Questions shown in Table 1.

Figure 6: Analysing attitude towards use (Q6, Q8, Q9, Q10) and Intent to use (Q7). Questions shown in Table 1.

Figure 7: Users’ preferences regarding type of interface (Avatar/ECA, No avatar/ECA). Questions shown in Table 1.

Evaluating the Impact on Usability and Acceptance of ECAs in m-Health Applications for Older Adults

43

The results of this study highlight the advantages

of integrating Embodied Conversational Agents

(ECAs) into applications aimed at older adults. The

ECA interfaces demonstrated higher acceptance in

the dimensions of perceived ease of use and attitude

towards use, suggesting that the interactive and

engaging nature of ECAs contributes positively to

user acceptance. Although some participants found

the ECA interface slightly more complex to navigate,

the majority appreciated its intuitiveness and reported

a reduced learning curve compared to the non-ECA

interface. Furthermore, the equal levels of intention to

use across both interfaces indicate that the perceived

utility of the application remains consistent,

regardless of interface type.

5.4 User App Preference

Questions Q14 to Q17 are intended to detect users’ app

preference, and their results are shown in Figure 7.

Question Q14, "Which application do you find

easier to use?," compares facility of use: 61% of the

participant considered the Non-ECA version (tactile)

easier to use, only 39% of them thought the ECA

interface was easier. This results is consistent with the

analysis of complexity done in relation to question Q2.

Question Q15, "With what application do you

understand the questions better?" compares facility of

use: 91% of the participants selected the ECA

version, only 9% the tactile/text interface.

Questions Q16 and Q17 focus on users’ feelings

during the interaction. In Q16 "With which

application did you feel better in the interaction?” the

ECA version was clearly favoured, as 87% chose it

and only13&% chose the non-ECA interface. Same

percentages were obtained in question Q17 “With

which application did you feel more comfortable

when interacting?”.

As it can be seen, the agent helps older adults to

feel more comfortable in the use of the applications,

during the interaction and led to a better

understanding of the questions. Nevertheless, they do

not find it easy to use.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Due to the aging population and the growing need to

closely monitor frail older adults, it becomes essential

to integrate technology into their environments and

contexts of use. Designing interfaces for this group

presents significant challenges, as many older adults

are reluctant or, at best, unmotivated to engage with

technology. Additionally, a considerable number face

vision, hearing, or cognitive impairments, and some

experience literacy difficulties.

ECAs interfaces support multimodal interaction,

may facilitate the transmission of emotions and at the

end may increase confidence and adherence. In this

paper, we present a study to analyse the use of this

kind of interfaces in m-health applications aimed to

older adults focusing in their usability and acceptance

by its users.

Our results show that with the use of ECAs, the

acceptance of m-health applications increases

compared to only tactile text-based interfaces. This is

true in two dimensions: perceived ease of use and

attitude towards use, being even in the intention to use

dimension. Moreover, older adults feel better and

more comfortable with the ECA interface (with a

preference for male characters with mild appearance)

and think they help them to answer the questions.

Nevertheless, this kind of interfaces are not seen

easier to use or funnier than traditional ones if they

are not carefully designed.

After the promising results obtained in this initial

work, other issues such as the study of agent’s

credibility, trustworthiness and its impact on user’s

adherence to the app have to be studied in next works.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Partially funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science

and Innovation through contract PID2022-

136779OB-C31. T60_23R Research Group in

Advanced Interfaces (AffectiveLab), Government of

Aragón. Research grant program 2024.

REFERENCES

Bérubé C, Schachner T, Keller R, Fleisch E, V

Wangenheim F, Barata F, Kowatsch T. (2021). Voice-

Based Conversational Agents for the Prevention and

Management of Chronic and Mental Health Conditions:

Systematic Literature Review. J Med Internet Res. Vol

23(3):e25933. doi: 10.2196/25933.

Bravo, S.L., Herrera, C. J., Valdez, E. C., Poliquit, K. J.

Ureta, J., Cu, J., Azcarraga, J.J., Rivera, J.P. (2020).

CATE: An Embodied Conversational Agent for the

Elderly. In Proc. of the 12th International Conference

on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART 2020),

vol 2, pp.941-948, doi: 10.5220/0009174009410948.

Cassell, J., & Bickmore, T. (2000). External manifestations

of trustworthiness in the interface. Communications of

the ACM, 43, pp. 50–56 http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/355

112.355123.

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

44

Cheong, W. L., Jung, Y. and Theng, Y.L. (2011) Avatar: a

virtual face for the elderly. In Proc. of the 10th

International Conference on Virtual Reality Continuum

and Its Applications in Industry, pp. 491-498. doi:

10.1145/2087756.2087850.

Dai, R. & Pan, Z. (2021). A virtual companion empty-nest

elderly dining system based on virtual avatars. In Proc.

IEEE 7th International Conference on Virtual Reality

(ICVR), pp. 446-451, doi: 10.1109/ICVR51878.2021.9

483852.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Technology acceptance model: TAM.

Al-Suqri, MN, Al-Aufi, AS: Information Seeking

Behavior and Technology Adoption, pp. 205, 219.

Esposito, A. et al. (2019). Seniors’ Acceptance of Virtual

Humanoid Agents. In Ambient Assisted Living, Cham,

pp. 429-443.

Esposito, A. et al. (2018) .Seniors’ sensing of agents’

personality from facial expressions. In Computers

Helping People with Special Needs, Cham, pp. 438-

442.

Franco dos Reis Alves, S. , Uribe Quevedo, A., Chen, D.,

Morris, J. and Radmard, S. (2021). Leveraging

Simulation and Virtual Reality for a Long Term Care

Facility Service Robot During COVID-19. In Proc.

Symposium on Virtual and Augmented Reality, pp. 187-

191. doi: 10.1145/3488162.3488185.

Navarro-Alamán, J., Gilaberte, R. L., & Bagdasari, E. C.

(2021). A proposal for the initial characterization of the

elderly to develop adaptive interfaces (in Spanish).

Revista de la Asociación Interacción Persona

Ordenador (AIPO), vol. 2(2), pp.34-41.

Nowakowska-Grunt, J., Dziadkiewicz, M., Olejniczak-

Szuster, K. & Starostka-Patyk, M.(2021). Quality of

service in local government units and digital exclusion

of elderly people - example from implementing the

avatar project. Pol. J. Manag. Stud., vol. 23, pp. 335-

352, doi: 10.17512/pjms.2021.23.2.20.

Pacheco-Lorenzo, M. R., Valladares-Rodríguez, S. M.,

Anido-Rifón, L. E. and Fernández-Iglesias, M. J.

(2021). Smart conversational agents for the detection of

neuropsychiatric disorders: A systematic review. J.

Biomed. Inform, vol. 113, p. 103632, doi:

10.1016/j.jbi.2020.103632.

Salman, S., Richards, D. and Caldwell, P. (2021). Analysis

of empathic dialogue in actual doctor-patient calls and

implications for design of embodied conversational

agents, IJCoL Ital. J. Comput. Linguist., vol. 7 (1|2),

doi: 10.4000/ijcol.862.

Shaked, N. A. (2017). Avatars and virtual agents –

relationship interfaces for the elderly. Healthc. Technol.

Lett., vol. 4(3), pp. 83-87, doi: 10.1049/htl.2017.0009.

Tanaka, H., et al. (2017). Detecting dementia through

interactive computer avatars. IEEE J. Transl. Eng.

Health Med., vol. 5, pp. 1-11, doi: 10.1109/JTEHM.

2017.2752152.

Thaler, M., Schlögl, S., and Groth, A. (2020) Agent vs.

Avatar: comparing embodied conversational agents

concerning characteristics of the Uncanny Valley. In

Proc. IEEE International Conference on Human-

Machine Systems (ICHMS 2020), pp. 1-6. doi:

10.1109/ICHMS49158.2020.9209539.

Turunen, M., Hakulinen, J., Ståhl, O., Gambäck, B.,

Hansen, P., Rodríguez-Gancedo, M.C., Santos de la

Cámara, R., Smith, C., Charlton, D., Cavazza,

M.(2011). Multimodal and Mobile Conversational

Health and Fitness Companions. Comput. Speech

Lang., vol. 25 (2), pp. 192-209, abr. 2011, doi:

10.1016/j.csl.2010.04.004.

Wargnier, P. et al.(2015). Towards attention monitoring of

older adults with cognitive impairment during

interaction with an Embodied Conversational Agent. In

Proc. IEEE VR International Workshop on Virtual and

Augmented Assistive Technology (VAAT 2015), pp. 23-

28, doi: 10.1109/VAAT.2015.7155406.

Evaluating the Impact on Usability and Acceptance of ECAs in m-Health Applications for Older Adults

45