Detection of Arm Swing Limitations in Simulated Parkinson’s

Disease Gait Conditions: A Pilot Study

Carlos Polvorinos-Fernández

1

a

, Luis Sigcha

2

b

, María Centeno-Cerrato

1

c

,

Elena Muñoz-Bellido

1

, César Asensio

3

d

, Juan Manuel López

4

e

, Guillermo de Arcas

1

f

and Ignacio Pavón

1

g

1

Instrumentation and Applied Acoustics Research Group, Mechanical Engineering Department,

ETS Ingenieros Industriales, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain

2

Department of Physical Education and Sports Science, Health Research Institute, & Data-Driven Computer Engineering

(D2iCE) Group, University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland

3

Instrumentation and Applied Acoustics Research Group, Department of Audiovisual Engineering and Communications,

ETS. de Ingeniería y Sistemas de Telecomunicación, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain

4

Instrumentation and Applied Acoustics Research Group, Department of Physical Electronics, Electrical Engineering and

Applied Physics, ETS. de Ingeniería y Sistemas de Telecomunicación, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain

Keywords: Wearables, Gait, Machine Learning, Accelerometer, Gyroscope.

Abstract: Human gait is a biomechanical process vital to health, with abnormalities often linked to neurological

disorders like Parkinson's disease (PD). In PD patients, arm swing during walking becomes asymmetric and

reduced in amplitude, providing a potential biomarker for early diagnosis and monitoring disease progression.

This pilot study focuses on detecting variations in arm swing amplitude and asymmetry using data collected

from smartwatches worn by 24 participants under different gait conditions. Participants walked while carrying

progressively heavier loads (0 kg, 2 kg, and 4 kg) to simulate restricted arm swing. Machine learning models

were developed to classify these conditions using accelerometer and gyroscope data. Results showed that the

K-Nearest Neighbours algorithm performed best, achieving up to 94.3% accuracy. Although the models

effectively distinguished between load and no-load conditions, it was difficult to differentiate between

different load levels. These findings highlight the potential of wearable devices for PD gait analysis, though

further refinement and testing with PD patients are needed for clinical application.

1 INTRODUCTION

Human gait is the biomechanical process of

locomotion, characterized by the coordinated,

rhythmic alternation of weight-bearing between the

lower limbs, enabling forward movement while

maintaining an upright posture. Although the walking

process is unique to everyone, commonalities exist

that enable the definition of a characteristic and

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4594-9477

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9968-5024

c

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-0113-3007

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3265-3244

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7847-8707

f

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1699-7389

g

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0970-0452

standardized pattern for normal human gait (Braune

& Fischer, 1987).

During gait, the central nervous system generates

oscillation of the arms to stabilise gait, regain balance

and reduce energy expenditure. Due to the close

relationship between arm swing and gait, it is

common for gait estimations, such as step counting,

to be derived by monitoring arm swing movements

(Meyns et al., 2013).

Polvorinos-Fernández, C., Sigcha, L., Centeno-Cerrato, M., Muñoz-Bellido, E., Asensio, C., López, J. M., de Arcas, G. and Pavón, I.

Detection of Arm Swing Limitations in Simulated Parkinson’s Disease Gait Conditions: A Pilot Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0013231600003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 2: HEALTHINF, pages 1029-1036

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

1029

Gait biomechanics is fundamental to health, as

various diseases can disrupt the mechanical

interactions involved, leading to impaired movement,

instability, or mobility limitations. Many gait

abnormalities arise involuntarily and are primarily

linked to neurological, musculoskeletal, or systemic

disorders, further impacting an individual's functional

capacity (Cicirelli et al., 2022).

Festinating gait, characterized by an accelerated

and unsteady walking pattern with short, rapid steps

that seem to propel the individual forward, is one of

the most common motor symptoms observed in

patients with Parkinson’s Disease (PD).

PD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder

that affects the central nervous system, resulting in

both motor and non-motor symptoms. The condition

arises when dopamine-producing neurons in the brain

become deficient, leading to impaired motor control

and other systemic effects (Wirdefeldt et al., 2011).

Symptoms of PD usually manifest gradually, with

a barely perceptible tremor in one hand often being

the initial sign in most cases. While tremors are

common, the disorder may also cause muscle

stiffness and reduced movement. The movements

become reduced in amplitude, speed, and symmetry,

leading to increased fatigue and the adoption of

compensatory postures to maintain balance (Morris et

al., 2001).

These motor symptoms affect not only gait in the

lower limbs but also arm swing. Therefore, in PD

patients, the arm swing has a lower amplitude,

cadence and step width during gait. In addition, the

PD usually manifests with more pronounced effects

on one side of the body., which causes the effects on

gait to be reflected asymmetrically, both in the legs

and in the arm swing (Djaldetti et al., 2006).

Individuals with PD demonstrated significantly

greater asymmetry in arm swing compared to those

without gait pathology (Lewek et al., 2010).

Based on this premise, the present case study was

designed. The objective is to develop a restricted arm

swing classifier focused on detecting variations in

amplitude and asymmetry using machine learning

models. To achieve this, an experiment was

conducted in which participants wore a smartwatch

and were subjected to progressively restricted gait

conditions, from least to most constrained, to simulate

different levels of restricted arm swing.

Under these restrictions, the braking speed of arm

swing is expected to be affected in a manner that can

be detected by the smartwatch. To simulate this

effect, different loads (0 kg, 2 kg, and 4 kg) were used

during various gait measurements. As the load

increases, a reduction in the swing angle is

anticipated, recreating similar conditions to the

movement restrictions experienced by PD patients.

The asymmetry in arm swing may serve as a

valuable biomarker for the early diagnosis of PD and

for monitoring disease progression in its initial stages.

2 BACKGROUND

In recent years, numerous studies have investigated

the potential of wearable devices for healthcare

applications. Some research has concentrated on the

development of specialized devices, like STAT-ON®

(Rodríguez-Martín et al., 2019), while others have

utilized commercially available devices to assess PD

symptoms (Polvorinos-Fernández, et al., 2024;

Sigcha et al., 2023). Wearable devices allow the

definition of a wide range of digital biomarkers

related to PD motor symptoms such as tremor,

bradykinesia or gait disturbances (Polvorinos-

Fernández, et al., 2024).

A study conducted by (Warmerdam et al., 2020)

using a wrist-worn inertial sensor to compare the gait

patterns of a healthy individual with those of a PD

patient exhibiting gait impairments. The results

revealed that the gait of the PD patients was non-

cyclical, with numerous fluctuations and

irregularities, in contrast to the healthy individual's

gait, which displayed a repetitive and cyclical pattern.

(Takami et al., 2020) performed gait tests using a

accelerometer measurement device with healthy

individuals under varying conditions: normal gait,

gait with one arm restricted, both arms restricted, and

exaggerated arm swing in the Wernicke-Mann

position. The results showed that, compared to

normal gait, arm swing velocity significantly

decreased when participants performed gait exercises

with one arm restricted or with no arm movement.

(Siragy et al., 2020) studied how PD patients with

and without arm swing restriction walked over

different terrains. The arm-swing analysis revealed

that PD patients appropriately reduced their step

length as a compensatory mechanism for the

restricted arm swing.

The need for advanced tools to improve the

diagnosis and continuous monitoring PD is

increasingly evident. The use of smart technologies

for managing diseases like PD is gaining popularity,

with wearable technologies standing out due to their

low cost, long battery life, and non-invasive nature.

These features make them ideal for developing

continuous monitoring systems for PD.

In the case of gait observation, providing

objective, gait-based measurements, wearable sensor

WHC 2025 - Special Session on Wearable HealthCare

1030

systems allow clinicians to personalize rehabilitation,

therapeutic, or pharmacological interventions to meet

each patient’s specific needs. This personalized

approach enhances treatment efficacy and contributes

to more effective management of disease progression.

This pilot study presents a starting point for the

identification of abnormal gait patterns in patients

with PD. The proposed algorithm could be used for

early detection of movement disorders, with a

specific focus on analysing braking dynamics during

gait, based on data collected from a wearable device.

3 MATERIALS AND METHODS

3.1 Data Collection

The data used in this study were collected during the

BIOCLITE project, using a custom-designed m-

health wearable application, which utilized

smartwatches to track motor symptoms in PD

patients.

Data were collected from a group of 24

volunteers, with a balanced gender distribution and

ages ranging from 24 to 40 years, with no known gait

pathology (Polvorinos-Fernández, et al., 2024). All

participants were persons without known pathologies

and performed the three specific activities outlined in

the protocol of this work. Data collection covered a

period of two days in which, in five to ten minutes

interval, each participant performed the three

proposed activities.

3.2 Acquisition Device

The BIOCLITE project use a commercial smartwatch

for data collection. During each of the measurement

sessions the smartwatch was worn on each patient's

preferred wrist. This wearable device allows to

collect movement signals in the time domain using its

built-in inertial sensors. For this study, the

accelerometer and gyroscope (along three axes) were

used for data collection. The accelerometer measured

in m/s², while the gyroscope measured in rad/s.

In this work, the smartwatch used for data

collection has a dimension of 39.3×40.4×9.8 mm and

a weight of 28.7g. The smartwatch is equipped with

an LSM6DS0 package, which integrates a 3-axis

digital gyroscope and a 3-axis digital accelerometer.

The sampling frequency is configured at 50 Hz.

This frequency was chosen because it is well-suited

for the analysis of human movement, which typically

focuses on a frequency range of 0.8 to 1.5 Hz during

normal and abnormal gait (Winter, 2009).

3.3 Experimental Protocol

During the data collection sessions, each participant

performed a test under different conditions to

approximate several gait conditions.

Each participant must walk in a straight line from

the starting point to a marked point, wait for 3 seconds

at that point, turn around to change the direction of

movement, wait another 3 seconds and walk back to

the starting point. Participants were instructed to

perform the test at their preferred walking speed,

repeating the process three times: once with no load,

a second time carrying a 2 kg weight, and a third time

carrying a 4 kg weight. This order was established to

try to avoid fatigue affecting the participants, even

though there was a rest period between each test.

For each participant and each performed test, a

researcher was responsible for starting the recording

of the data from the smartwatch, indicating to the

participants the start of the test, logging the exact time

at which the test had started, and, once the test had

been completed, stopping the measurement. In this

case, the activities were not recorded with a video

camera due to patient privacy issues.

The measurement track was a straight corridor

where the point of departure and return was marked

with a cross on the ground. The straight section is 30

metres long, and the corridor is more than 5 metres

wide, which allowed the measurement session to be

carried out without any problems.

For each participant and activity, a new file was

created. Therefore, considering that there were 24

participants and 3 different activities, a total of 72

data files were obtained.

3.4 Data Labelling

For data labelling, the name of the files generated

with the custom-designed m-health smartwatch

application was essential. This name identifies which

device was used (this information is not valid for this

study given that all the performed tests were carried

out with the same device) together with the date on

which it was created and the exact time at which the

recording was started.

Based on this date and time, each of the records

was assigned a person label (1 to 24) and an activity

label (1 for no load gait, 2 for 2 kg gait and 3 for 4 kg

gait), correlating with the manual registration made

by the person in charge of the trials, who takes notes

of which person carried out each activity as well as

the starting time. These labels were then reviewed by

viewing each file to ensure that they matched and

contained valid data records.

Detection of Arm Swing Limitations in Simulated Parkinson’s Disease Gait Conditions: A Pilot Study

1031

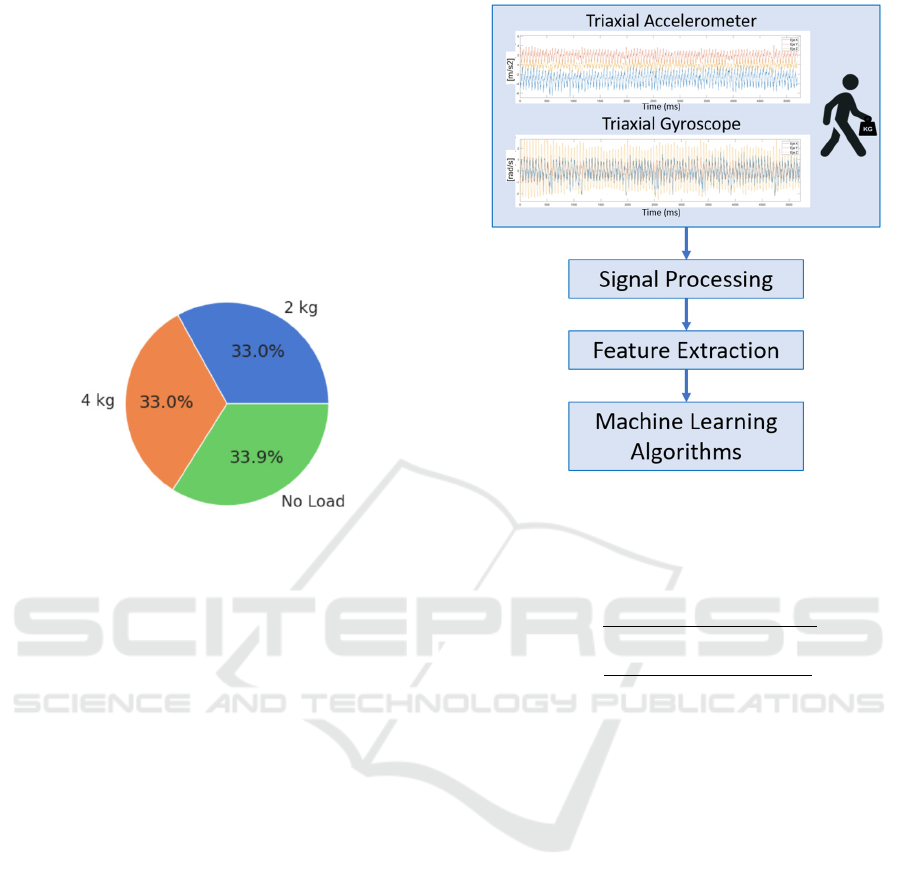

Figure 1 shows the distribution of data collected

according to the activity label. It can be observed that

the distribution is homogeneous among the 3 gait

conditions. The slight differences observed between

activities can be attributed to the fact that participants

were allowed to choose the speed at which they

performed each test. Consequently, variations in

walking speed among participants resulted in

differences in the number of samples collected, as the

sampling rate is the same for all the subjects. The

activity with the highest number of samples is the one

related to walking without loads.

Figure 1: Distribution of data collected according to the

activity label.

3.5 Algorithmic Approach

This paper presents machine learning models

designed to predict the level of hand movement

constraint (free, 2 kg or 4 kg) using data from

accelerometer and gyroscope. The development of

these models followed the schema shown in Figure 2.

To train and evaluate the proposed models, the

signal obtained from the smartwatch must be

processed to get better results.

First, the valid parts of each of the records were

selected, as the periods from the start of the recording

until the person starts walking, the standing period

before and after the turn, the turn itself, and the period

from the end of the activity until the end of the

recording were not used. As a result, since there are

two gait periods for each record (outward and return),

the final database of 144 valid records was defined.

On this basis, this study was performed using two

different databases. On the one hand, the

accelerometer and gyroscope signals from each of the

3 axes were used independently (6 signals in total).

On the other hand, the signal obtained from each of

the three axes of each sensor was combined into one

by means of Euclidean Norm according to equations

1 and 2 (2 signals in total). This is since the inertial

sensors embedded in the wearable device can have a

random orientation, so this combination has been

performed to avoid errors. In addition, during the

Figure 2: Algorithm approach diagram.

experimental phase, the participants placed the

smartwatch in different ways and the orientation of

the watch is different for the left and the right hand.

𝐴

𝑐𝑐𝑒𝑙

𝑎𝑐𝑐𝑒𝑙

𝑎𝑐𝑐𝑒𝑙

𝑎𝑐𝑐𝑒𝑙

(1)

𝐺𝑦𝑟𝑜

𝑔𝑦𝑟𝑜

𝑔𝑦𝑟𝑜

𝑔𝑦𝑟𝑜

(2)

After calculating the Eucliden norm, the

following steps to be explained apply both to the 3

axes separately and to the combination of these. The

signal was filtered using a 3-order Butterworth band-

pass filter in the frequency range between 0.5 and 10

Hz. This range is appropriate for human activity

recognition, in particular, human gait (Winter, 2009).

After adjusting the signal to the desired frequency

range, it was segmented into 128-sample windows

(2.56 seconds) with a 50% overlap. For the 144

records, 2454 windows were generated. This

combination of windowing and overlapping is

suitable for different PD motor symptoms analysis

(Patel et al., 2009; Sigcha et al., 2021). As the data is

divided by records and each one corresponds to a

different participant and activity, dividing each of

these records into windows did not create a problem

regarding labelling, as all the windows had the same

labels associated with their source records.

Then, the signal was converted to the frequency

domain using the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). This

was because it is expected that the dominant

WHC 2025 - Special Session on Wearable HealthCare

1032

frequencies of braking during walking will allow a

correct differentiation between individuals walking

freely and those carrying varying weights., so

bringing the data into the frequency domain can be a

key aspect to obtain good results. Since the sampling

frequency is defined as 50 Hz, the maximum

frequency for which data is available is 25 Hz (higher

than the usual frequency of human movement). In this

case, 65 spectral lines were calculated using the FFT,

each with a bandwidth of approximately 0.38 Hz.

For this work, the extracted features correspond to

the amplitude of each of the 65 spectral lines of each

signal. For the database formed by the original signals

in 3 axes, and for 2 sensors (accelerometer and

gyroscope), we will have 390 features. In the database

composed of the Euclidean signal of accelerometer

and gyroscope, 130 features will be calculated. In

both databases, all the proposed features were

calculated for the 2454 defined windows.

After the feature extraction process, machine

learning models were developed, trained, validated,

and analysed with the two databases independently to

evaluate their performance and effectiveness in

addressing the study objectives. For the training and

testing of the models, the windows defined for 21 of

the 24 participants were divided into 60% training

and 40% test, using Hold Out Validation. The 3

remaining participants (randomly selected) were used

to validate the trained models, with the aim of testing

the reliability of the models on data never seen before.

For this work, the variable to be predicted is the

one corresponding to the activity category, related to

whether, during the walk, the person was walking

without load (label 0), with 2 kg (label 1) or with 4 kg

(label 2). Since the target variable is categorical,

classification models were employed. The models

used in this study include Gradient Boosting (GB),

AdaBoost (ADAB), K-Nearest Neighbours (KNN),

Random Forest (RF), and Decision Tree (DT). The

models were evaluated using accuracy, recall,

specificity, precision, and F1-score metrics.

4 EXPERIMENTS AND RESULTS

This section presents the results obtained from the

study, which involved conducting various

experiments with different datasets. Section 4.1

details the results derived from the 3-axis signals of

the accelerometer and gyroscope. Section 4.2

presents the findings based on the Euclidean norm of

the combined signals from both sensors. In each

section, the model with the best performance was

identified, and validation of this model was carried

out using data from three randomly selected subjects.

4.1 Results of the Training Models

Using the 3-Axis Database

The classification models proposed in Section 3.5

were implemented and trained using the dataset of

390 features extracted from the frequency domain for

each triaxial signal of accelerometer and gyroscope.

First, it will be determined which of the models

proposed is the one that offers the best performance.

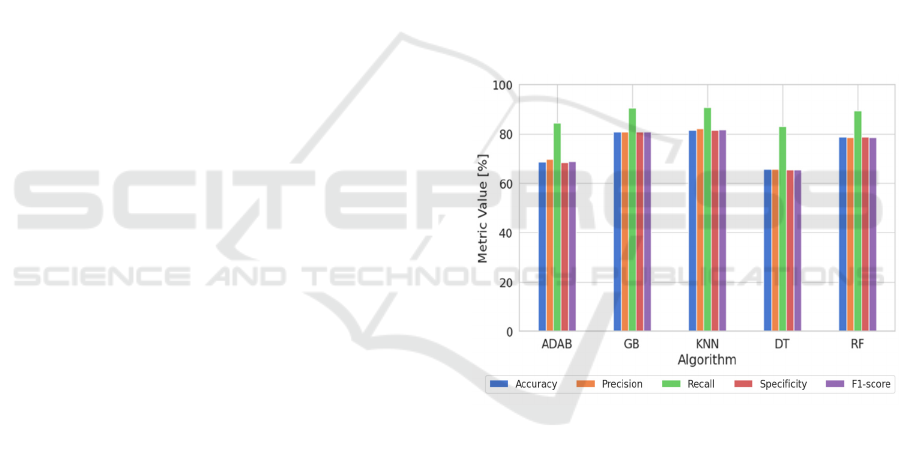

Figure 3 show the metrics obtained for each trained

machine learning model using the testing data.

It is noteworthy that recall values are high across

all models. This indicates that the models effectively

identify most of the true positive cases, i.e. the models

are less likely to miss relevant cases, which makes

them suitable for tasks where it is a priority to capture

all positive cases, such as in medical diagnosis, of

possible application in this study.

Figure 3: Metrics comparison for the proposed algorithm

using 3-axial accelerometer and gyroscope test data.

The analysis revealed that the KNN algorithm

demonstrated the best performance among the

evaluated models., with an accuracy of 81.5 %, a

precision of 82.0 %, a recall of 90.8 %, a specificity

of 81.4 % and a F1-score of 81.6 %. On the opposite

side, the worst model is the DT with 69.4 %, 69.3 %,

84.8 %, 69.2 % and 69.1 % in respective metrics.

Table 1 shows in detail the metrics obtained with the

test dataset for the best model.

It can be noticed that there is a trend towards

classification performance. For the identification of

no-load gait, related to the movement without loads,

the specificity, recall, precision and f1-score metrics

have a high performance, between 88,01 % to

98,42%. On the other hand, for observations related

Detection of Arm Swing Limitations in Simulated Parkinson’s Disease Gait Conditions: A Pilot Study

1033

to loaded movement, these metrics are relatively

lower, with values from 74,22% to 87,19 %.

However, the overall accuracy of the 3 categories is

81.51 %, which is quite high, considering that we are

working with a not very extensive database.

Table 1: Metrics obtained for KNN algorithm for the 3-axis

test dataset.

[%] No Load 2 kg 4 kg

Accuracy 81,5

Precision 96,6 74,2 75,2

Recall 88,0 75,5 80,8

Specificity 98,4 87,2 86,8

F1-score 92,1 74,9 77,9

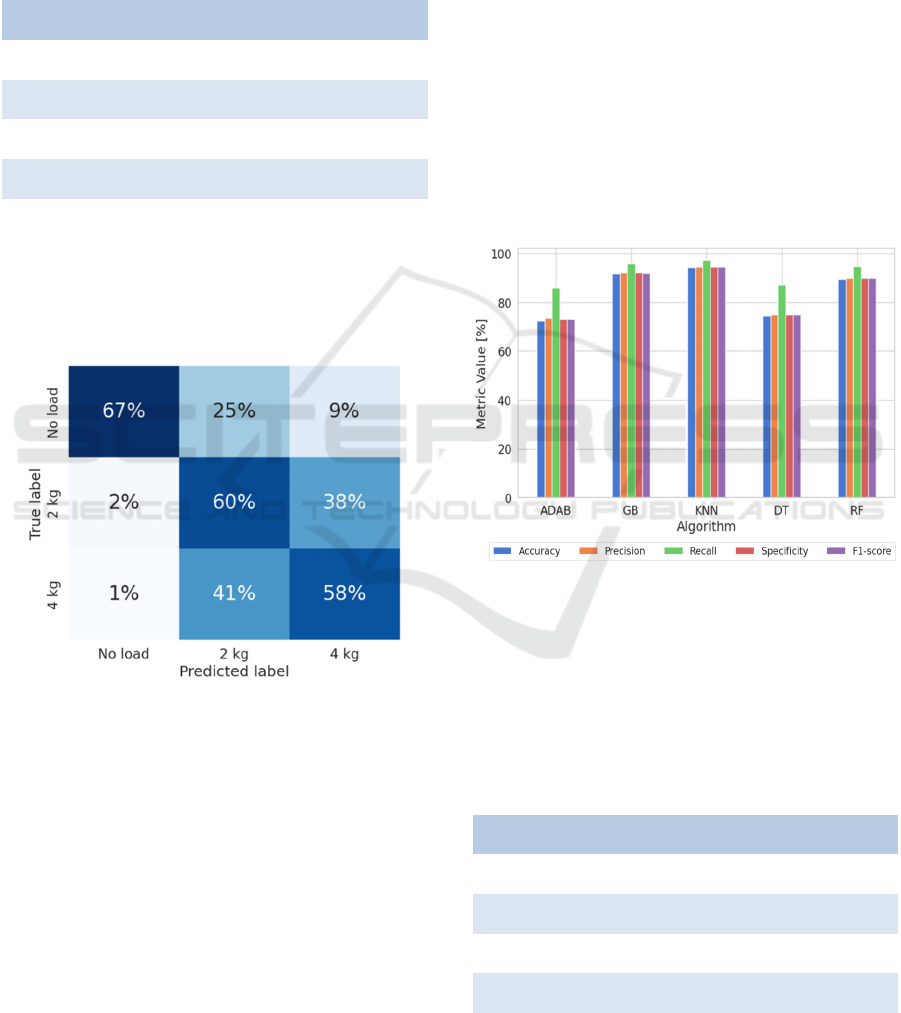

Once the best model has been determined, it will

be used for validation with the 3 randomly selected

subject data. The confusion matrix, shown in Figure

4, will be used for this purpose.

Figure 4: Normalized Confusion Matrix for the 3-axis

validation dataset.

It can be observed that the differentiation between

walking with loads and without loads can be done

relatively easily. Moreover, the algorithm is more

wrong predicting that it is loaded when it is free

(34%) than in interpreting that it is free when it is

loaded (3%). However, distinguishing between label

1 (2 kg load) and label 2 (4 kg load) is a challenging

task. The model misclassifies label 1 as 2 38% of the

windows and label 2 as 1 in 41% of cases.

4.2 Results of the Training Models

Using the Combined Signal

Database

In this section we will present the study proposed in

the previous section using a different database, the

one composed of the triaxial accelerometer and

gyroscope signals combined using the Euclidean

standard. In comparison with the previous case, it will

be moved from dealing with a signal of 6 different

channels to one with only 2.

Figure 5 shows the metrics obtained with the test

dataset associated to the trained models. It can be

noticed that the values obtained are higher than those

obtained in the previous section. While in section 4.1

the results were between 65% and 90%, those

calculated with the database of the combined signals

have obtained values between 72% and 98%.

Figure 5: Metrics comparison for the proposed algorithm

using combined accelerometer and gyroscope test data.

Again, the best performing model is the KNN

algorithm. The worst performer, meanwhile, is the

ADAB algorithm. Table 1 shows in detail the metrics

obtained for the best model with the test dataset.

Table 2: Metrics obtained for KNN algorithm for the

combined signal test dataset.

[%] No Load 2 kg 4 kg

Accuracy 94,30

Precision 99,63 91,50 92,28

Recall 99,83 95,34 96,15

Specificity 99,26 92,72 91,32

F1-score 99,44 92,11 91,79

WHC 2025 - Special Session on Wearable HealthCare

1034

The trend continues to be that label 1 is the one

with the best metrics, i.e. the one that is most

accurately identified. Accuracy, recall, specificity

and F1 score all have values around 99%. These

metrics for labels 2 and 3, corresponding to loaded

gait, are around 92%. The accuracy is around 94%,

higher than in the previous case.

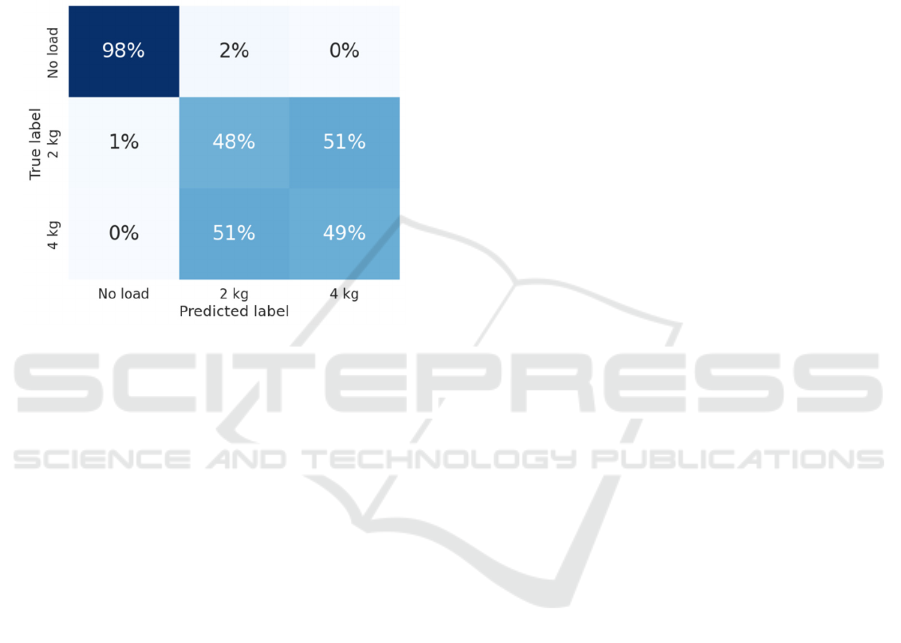

With the best model identified, it will be validated

using data from the 3 randomly selected subjects. The

confusion matrix, shown in Figure 5, will be utilized.

Figure 6: Normalized Confusion Matrix for the combined

signal validation dataset.

In this case, the trend mentioned in the previous

analysis becomes more pronounced as it is very

accurate in identifying the unloaded gait with a 98%

accuracy rate. On the other hand, when dealing with

the loaded gait data, the predictions are not at all

accurate, as it is only 50% correct to differentiate

between 2 and 4 kg. In fact, it predicts as 4 kg when

it is really 2 kg in 51% of the cases and the same

happens in the opposite case, interpreting that it is 2

kg when it is really 4 kg.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study developed and evaluated machine learning

models for detecting arm swing constraints in

simulated gait conditions, trying to be like the gait

patterns of PD patients.

By utilizing accelerometer and gyroscope data

from smartwatches, the machine learning models

were able to classify participants walking under three

conditions: no load, 2 kg load, and 4 kg load.

KNN model demonstrated the highest accuracy in

both the 3-axis and Euclidean norm-based datasets,

proving effective in distinguishing between loaded

and unloaded gait patterns. However, while the

models performed well in detecting the presence of a

load, they encountered difficulties differentiating

between the 2 kg and 4 kg weights, indicating that

further refinement is needed for more nuanced

classification.

One possible explanation is that

walking without a load, as opposed to carrying any

load, induces significant changes in body posture,

stride, and movement dynamics that can be

effectively captured by the signals employed.

However, when differentiating between loads, these

differences may not be as pronounced.

Using the 3-axis dataset with the validation data

set, it manages to differentiate the no load cases 67%

of the time, the 2kg load cases 60% of the time and

the 4kg load cases 58% of the time. For the combined

signal dataset, on the other hand, this distribution

changes, as the no load cases are matched 98% of the

time while the 2 and 4 kg load cases are matched

around 50% of the time.

This evaluation highlights the potential utility of

each dataset employed in the analysis. The combined

signal could be used to distinguish load and no-load

cases while the 3-axial signal could be used to

distinguish between different load situations.

It is important to acknowledge that this study has

certain limitations that should be addressed in future

research studies. The database consists of

measurements from 24 healthy patients with no

known gait pathology. In addition, no real PD patients

have been involved, which would be interesting

especially for the validation of the models.

Future work should focus on exploring the

applicability of this type of test in PD patients to

evaluate its practical utility, expanding the database

by increasing the number of participants and

incorporating diverse settings, such as varying

loading conditions or extended durations, to study

variability. Furthermore, it would be valuable to

investigate additional machine learning algorithms,

including traditional and recent advancements, such

as deep learning, to enhance performance.

In practical implementation, several

considerations must be addressed to transition this

approach to real-world applications effectively.

Smartwatches offer a non-intrusive platform for long-

term monitoring; however, ensuring usability and

fostering patient compliance remain crucial

challenges. Validation of the system with PD patients

across diverse daily living scenarios is necessary to

establish model robustness and reliability under real-

world conditions. Additionally, implementing secure

and efficient data transmission mechanisms is

essential to safeguard patient privacy and ensure

reliability in remote monitoring applications.

Detection of Arm Swing Limitations in Simulated Parkinson’s Disease Gait Conditions: A Pilot Study

1035

Addressing these factors will significantly enhance

the practical utility and scalability of this approach.

The findings of this study suggest that wearable

sensor data combined with machine learning

techniques offer valuable potential for gait analysis,

with applications in the early diagnosis and

monitoring of movement disorders such as PD.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research has been possible thanks to the

financing of the project BIOCLITE: PID2021-

123708OB-I00, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/

501100011033/ FEDER, EU.

REFERENCES

Braune, W., & Fischer, O. (1987). The Human Gait.

Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-70326-3

Cicirelli, G., Impedovo, D., Dentamaro, V., Marani, R.,

Pirlo, G., & D’Orazio, T. R. (2022). Human Gait

Analysis in Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Review.

IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics,

26(1), 229–242. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and

Health Informatics.

https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2021.3092875

Djaldetti, R., Ziv, I., & Melamed, E. (2006). The mystery

of motor asymmetry in Parkinson’s disease. The Lancet

Neurology, 5(9), 796–802.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70549-X

Lewek, M. D., Poole, R., Johnson, J., Halawa, O., & Huang,

X. (2010). Arm swing magnitude and asymmetry

during gait in the early stages of Parkinson’s disease.

Gait & Posture, 31(2), 256–260.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2009.10.013

Meyns, P., Bruijn, S. M., & Duysens, J. (2013). The how

and why of arm swing during human walking. Gait &

Posture, 38(4), 555–562.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2013.02.006

Morris, M. E., Huxham, F., McGinley, J., Dodd, K., &

Iansek, R. (2001). The biomechanics and motor control

of gait in Parkinson disease. Clinical Biomechanics,

16(6), 459–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0268-

0033(01)00035-3

Patel, S., Lorincz, K., Hughes, R., Huggins, N., Growdon,

J., Standaert, D., Akay, M., Dy, J., Welsh, M., &

Bonato, P. (2009). Monitoring motor fluctuations in

patients with Parkinson’s disease using wearable

sensors. IEEE Transactions on Information Technology

in Biomedicine: A Publication of the IEEE Engineering

in Medicine and Biology Society, 13(6), 864–873.

https://doi.org/10.1109/TITB.2009.2033471

Polvorinos-Fernández, C., Pavón, I., & Sigcha, L. (2024).

Smartwatch gait dataset in simulated Parkinson’s

disease restricted arm swing conditions (Version V1.0)

[Dataset]. Zenodo.

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13884808

Polvorinos-Fernández, C., Sigcha, L., Borzì, L., Olmo, G.,

Asensio, C., López, J. M., de Arcas, G., & Pavón, .

(2024). Evaluating Motor Symptoms in Parkinson’s

Disease Through Wearable Sensors: A Systematic

Review of Digital Biomarkers. Applied Sciences,

14(22), Article 22.

https://doi.org/10.3390/app142210189

Polvorinos-Fernández, C., Sigcha, L., Pablo, L. P. de,

Borzí, L., Cardoso, P., Costa, N., Costa, S., López, J.

M., Arcas, G. de, & Pavón, I. (2024). Evaluation of the

Performance of Wearables’ Inertial Sensors for the

Diagnosis of Resting Tremor in Parkinson’s Disease. 2,

820–827. https://doi.org/10.5220/0012571600003657

Rodríguez-Martín, D., Pérez, C., Samà Monsonís, A.,

Català, A., Cabestany, J., & Rodríguez-Molinero, A.

(2019). STAT-ON: A Wearable Inertial System to

Objectively Evaluate Motor Symptoms in Parkinson’s

Disease.

Sigcha, L., Pavón, I., Costa, N., Costa, S., Gago, M.,

Arezes, P., López, J. M., & Arcas, G. D. (2021).

Automatic Resting Tremor Assessment in Parkinson’s

Disease Using Smartwatches and Multitask

Convolutional Neural Networks. Sensors (Basel,

Switzerland), 21(1), 291.

https://doi.org/10.3390/s21010291

Sigcha, L., Polvorinos-Fernández, C., Costa, N., Costa, S.,

Arezes, P., Gago, M., Lee, C., López, J. M., de Arcas,

G., & Pavón, I. (2023). Monipar: Movement data

collection tool to monitor motor symptoms in

Parkinson’s disease using smartwatches and

smartphones. Frontiers in Neurology, 14.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2023.1326640

Siragy, T., MacDonald, M.-E., & Nantel, J. (2020).

Restricted Arm Swing in People With Parkinson’s

Disease Decreases Step Length and Time on

Destabilizing Surfaces. Frontiers in Neurology, 11,

873. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.00873

Takami, A., Cavan, S., & Makino, M. (2020). Effects of

arm swing on walking abilities in healthy adults

restricted in the Wernicke-Mann’s limb position.

Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 32(8), 502–505.

https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.32.502

Warmerdam, E., Romijnders, R., Welzel, J., Hansen, C.,

Schmidt, G., & Maetzler, W. (2020). Quantification of

Arm Swing during Walking in Healthy Adults and

Parkinson’s Disease Patients: Wearable Sensor-Based

Algorithm Development and Validation. Sensors

(Basel, Switzerland), 20(20), 5963.

https://doi.org/10.3390/s20205963

Winter, D. A. (2009). Biomechanics and Motor Control of

Human Movement. Wiley. 10.1002/9780470549148

Wirdefeldt, K., Adami, H.-O., Cole, P., Trichopoulos, D.,

& Mandel, J. (2011). Epidemiology and etiology of

Parkinson’s disease: A review of the evidence.

European Journal of Epidemiology, 26 Suppl 1, S1-58.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-011-9581-6

WHC 2025 - Special Session on Wearable HealthCare

1036