From Big Idea to Prototype: A Challenge-Based Learning Framework

for Hackathons in Higher Education

Efra

´

ın Ort

´

ız-Pab

´

on

1 a

, Lady Fern

´

andez-Mora

2 b

, Nestor Armando Nova-Ar

´

evalo

3 c

and Juan E. G

´

omez-Morantes

1 d

1

Facultad de Ingenier

´

ıa, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogot

´

a, Colombia

2

Instituto Tecnol

´

ogico de Costa Rica, CTEC Campus San Carlos, Alajuela, Costa Rica

3

Facultad de Comunicaci

´

on y Lenguaje, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogot

´

a, Colombia

Keywords:

Hackathon, Challenge-Based Learning, Prototyping, Minimum Viable Product, Digital Innovation, Tourism

4.0, Smart Tourism.

Abstract:

This paper introduces the Hack4CBL framework, which integrates Challenge-Based Learning (CBL) princi-

ples into hackathon design to enhance multidisciplinary education in higher education settings. By aligning

the stages of a hackathon—pre-hackathon, hackathon, and post-hackathon—with the CBL domains of engage,

investigate, act, and transfer, the framework fosters meaningful collaboration among students pursuing diverse

learning outcomes within the same project. We illustrate the effectiveness of Hack4CBL through a binational

hackathon centered on Tourism 4.0, involving over 200 undergraduate students from Colombia and Costa Rica

across disciplines like systems engineering, computer engineering, business administration, tourism manage-

ment, and data science. Students formed interdisciplinary teams to tackle real-world challenges provided

by industry professionals, leading to the development of Minimum Viable Products (MVPs) over two months.

Results indicate that integrating CBL into hackathons enhances collaboration, deepens domain-specific knowl-

edge, and accelerates professional skill development. The Hack4CBL framework offers a replicable model for

leveraging hackathons as powerful educational platforms closely aligned with professional realities.

1 INTRODUCTION

Hackathons are short, collaborative events where di-

verse stakeholders innovate, create solutions, and de-

velop working software or prototypes, typically over

one to three days (Komssi et al., 2015). Over time,

they have evolved in both format and duration, rang-

ing from strictly in-person to virtual events, with flex-

ible time frames depending on the project’s scope.

The complexity of the challenges, the team dy-

namics, and the logistical aspects of organizing these

events all contribute to the development of valu-

able skills in participants, such as problem-solving,

teamwork, communication, adaptability, and techni-

cal proficiency. Because of this, hackathons have in-

creasingly been used as an educational strategy for

undergraduate and graduate students (Paganini and

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2309-6880

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4985-5128

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2624-8314

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8107-4030

Gama, 2020). However, achieving these outcomes de-

mands careful planning, strong coordination, and ef-

fective communication tools to handle logistical com-

plexities.

The main challenge in large hackathons with stu-

dents from a wide range of disciplines, courses, and

abilities is addressing the different expectations, skill

levels, and learning outcomes. In these contexts, one-

dimensional or narrowly focused projects risk disen-

gagement and skill under-utilization. To counter this,

hackathon challenges should be complex and multi-

faceted, such as developing an app that streamlines

healthcare access for under-served populations, inte-

grating patient data, tele-medicine, social work, and

predictive analytics. This approach fosters collabora-

tion, leverages unique perspectives, and promotes in-

terdisciplinary skill development, enabling innovative

solutions to emerge.

To address these challenges, we propose a frame-

work for hackathon development based on challenge-

based learning (CBL) (Nichols and Karen, 2008),

which engages participants in solving real-world

670

Ortíz-Pabón, E., Fernández-Mora, L., Nova-Arévalo, N. A. and Gómez-Morantes, J. E.

From Big Idea to Prototype: A Challenge-Based Learning Framework for Hackathons in Higher Education.

DOI: 10.5220/0013233400003932

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2025) - Volume 2, pages 670-677

ISBN: 978-989-758-746-7; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

problems through collaborative, hands-on experi-

ences requiring critical thinking and creativity. CBL-

driven hackathons require multidisciplinary collabo-

ration because teams will be facing a real and com-

plex challenge with multiple perspectives–they de-

mand expertise in areas such as technology, social

impact, ethics, business, and domain-specific knowl-

edge. This approach allows participants to engage

with authentic issues while applying knowledge from

their respective fields. As a result, it enhances indi-

vidual learning outcomes while also fostering purpose

and commitment by addressing real-world needs.

The framework is illustrated through a case study

involving a large-scale hackathon that engaged uni-

versity students from two countries and four dif-

ferent disciplines. This case study provides a de-

tailed analysis of the hackathon’s design, implemen-

tation, and outcomes, highlighting the effectiveness of

the CBL framework for hackathon design. Through

this approach, we aim to showcase the potential of

hackathons not only as tools for rapid prototyping

and problem-solving but also as powerful educational

platforms for developing interdisciplinary skills and

fostering a collaborative mindset.

After this introduction, section 2 discusses CBL

as a general pedagogical framework and its relevance

for the design of hackathons. Later, section 3 dis-

cusses hackathons as a general pedagogical strategy,

their potential, and limitations. Section 4 presents

the Hack4CBL framework for the development of

hackathons based on CBL principles, while section

5 presents how was this framework used to develop

a bi-national hackathon between Colombia and Costa

Rica centered on tourism 4.0. Finally, sections 6 and

7 discuss the main lessons from the hackathon and

conclude the paper.

2 CHALLENGE-BASED

LEARNING

Developing soft skills in engineering students is cru-

cial but challenging. With the modernization of en-

gineering education, many guidelines and pedagog-

ical systems have been created to enhance practi-

cal, business-focused, real-world, and entrepreneurial

training (Mart

´

ınez and Crusat, 2017). Experiential

learning (Kolb, 1983; Jamison et al., 2022), includ-

ing project-based and service learning (Chanin et al.,

2018), has traditionally addressed this need. This

work focuses on Challenge-Based learning (Nichols

and Karen, 2008).

CBL is an educational approach that engages stu-

dents in real, context-related problems by defining

a challenge and implementing a solution (Nichols

and Karen, 2008). Its emphasis on real-world prob-

lems, interdisciplinary collaboration, creativity, active

learning, and reflection has made it popular in STEM

education (Conde et al., 2021). In CBL, students, pro-

fessors, and other stakeholders collaborate to solve a

challenge in which creative and divergent thinking is

encouraged. Furthermore, the focus is not only on

the final deliverable but also on the entire process, as

students periodically reflect on the evolution of their

learning (Chanin et al., 2018).

The reference framework for the Challenge-Based

Learning process begins with a big idea and leads to

an essential question, a challenge, guiding questions,

activities, resources, solution determination and ar-

ticulation, action through solution, implementation,

reflection, evaluation, and publication (Nichols and

Karen, 2008). Table 1 describes these components.

The CBL framework is typically implemented

as either CBL courses or CBL projects (Doulougeri

et al., 2024). In CBL courses, a CBL component

promotes active learning of the course subject matter,

with the challenge and solution serving as a means

to that end. In contrast, CBL projects focus on the

challenge and its solution as the ultimate goal, of-

ten as graduation projects or extracurricular activi-

ties. Hackathons are a common form of extracurricu-

lar CBL projects (Doulougeri et al., 2024), but there

is limited guidance on adapting the CBL framework

to a hackathon format. This gap becomes apparent

in multidisciplinary hackathons within higher educa-

tion, where diverse student learning outcomes must

be addressed.

3 HACKATHONS

Hackathons are “events where computer program-

mers and others collaborate intensively over a short

period to develop software projects” (Komssi et al.,

2015, p.60). In CBL contexts, including non-

programmers like designers and domain experts en-

hances interdisciplinary collaboration and enriches

problem-solving.

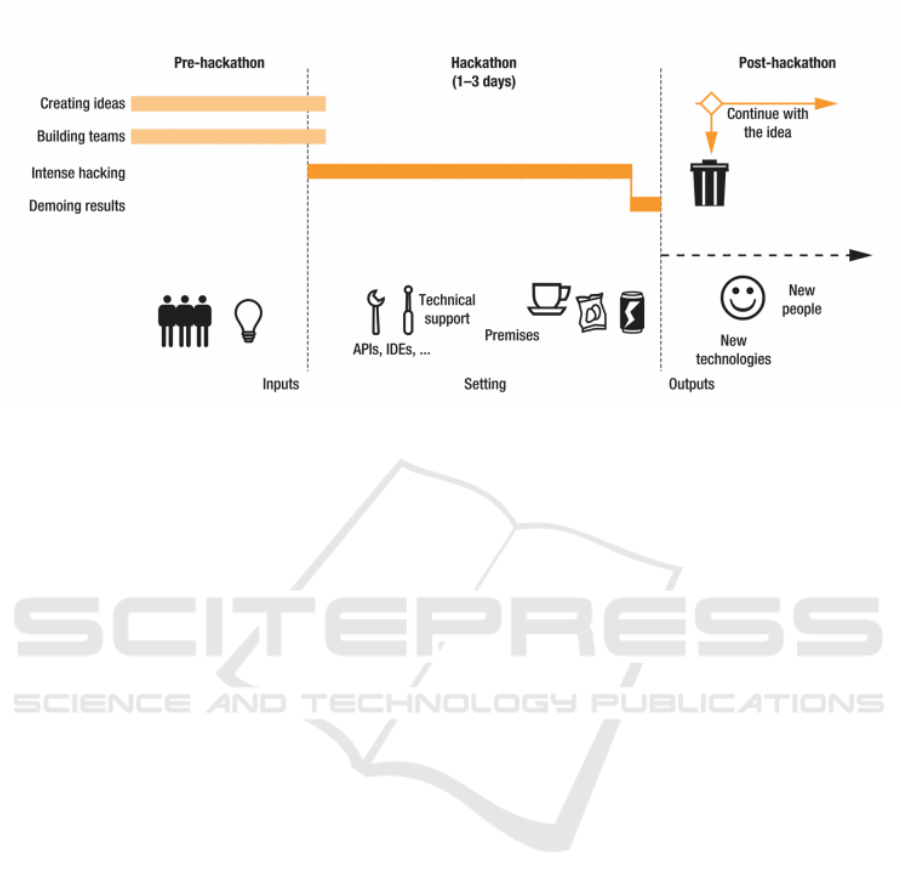

They follow a format that begins with team for-

mation and ideation (pre-hackathon or inputs), then

progresses to the actual hackathon, and then the post-

hackathon stage, where teams decide to continue or

discard the idea (Komssi et al., 2015). This is illus-

trated in Figure 1.

There is no universal or standardized form of

hackathon. Instead, the literature, as well as univer-

sity and corporate settings, display a range of vari-

ations depending on the anticipated outcomes (Por-

From Big Idea to Prototype: A Challenge-Based Learning Framework for Hackathons in Higher Education

671

Table 1: Components and Descriptions of Challenge-Based Learning. Source: (Nichols and Karen, 2008).

Component Description

Big Idea Broad concept that can be explored in multiple ways, has the quality of being ap-

pealing, and is important to the students and society at large. Examples of big ideas

include identity, sustainability, creativity, violence, peace, power, among others.

Essential

Question

Questions generated from the big idea. They should reflect the interests of the students

and the needs of the community. The essential questions identify what is important to

know about the big idea.

The Challenge A challenge is articulated from each essential question, asking students to create a

specific response or solution that can result in concrete and meaningful action.

Guiding Ques-

tions

Generated by the students, these questions represent the knowledge students need to

discover in order to successfully address the challenge.

Guiding Ac-

tivities

Lessons, simulations, games, and other types of activities that help students answer the

guiding questions and lay the foundation for them to develop innovative, insightful,

and realistic solutions.

Guiding Re-

sources

This focused set of resources may include sources, databases, experts, etc., that sup-

port the activities and help students develop a solution.

Solutions Each challenge is broad enough to allow for a variety of solutions. Each solution

should be thoughtful, concrete, viable, clearly articulated, and presented in a publish-

able multimedia format, such as an enhanced podcast or a short video.

Assessment The solution can be assessed based on its connection to the challenge, the accuracy

of the content, the clarity of communication, the applicability for implementation,

and the effectiveness of the idea, among other factors. In addition to the solution,

the process that individuals and teams went through to reach a solution can also be

evaluated, capturing the development of key skills or competencies.

Publication The challenge process provides multiple opportunities to document the experience

and publish it for a wider audience. Students are encouraged to publish their results

online and seek feedback. The idea is to expand the learning community and foster

discussion about solutions to challenges that are important to students.

ras et al., 2018). These events are often referred to

by different names, such as hackfests, code camps,

datathons (Anslow et al., 2016), or jams. It is worth

noting that jams do not necessarily require program-

ming; however, they may include it and are frequently

associated with specific disciplines, such as video

game design or service design (Komssi et al., 2015).

This variety calls for a unified framework to guide

the design and development of hackathon events in

higher education following the CBL framework. This

is tackled in the following section and is illustrated

with a case study in section 5.

4 METHODOLOGY

A unifying framework was created for this hackathon

by integrating the three hackathon stages (pre-,

hackathon, post-) shown in Figure 1, the CBL frame-

work (see Table 1), and the three domains from

(Chanin et al., 2018)–engage, investigate, act. A

fourth domain, ‘transfer,’ was added to ensure that

learning and outcomes extend beyond the event, fos-

tering long-term impact and knowledge sharing.

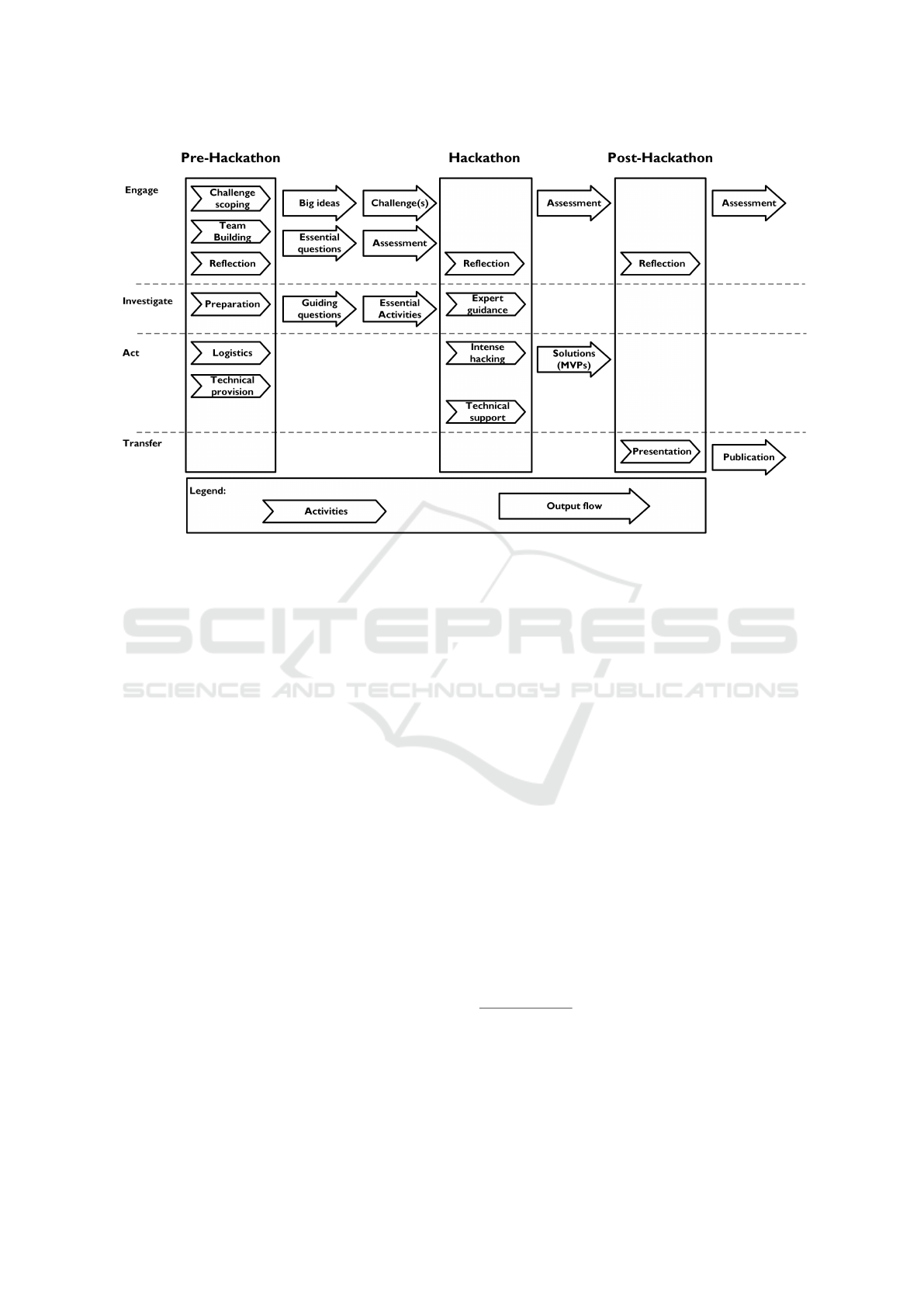

The Hack4CBL framework, shown in Figure 2,

structures hackathons for challenge-based learning in

three stages: pre-hackathon, hackathon, and post-

hackathon. Each stage includes activities in four do-

mains, which may be executed in any order, prefer-

ably in parallel. Once outputs of a stage are secured,

the team can move on, and multiple iterations may be

conducted at each stage as needed.

The main contribution of CBL to the Hack4CBL

framework is the opportunity for multi-learning-

outcome (multi-LO) processes. That is, learning pro-

cesses in which students from multiple disciplines

pursue different learning outcomes while participat-

ing in the same project (Nicolescu, 2014). With

its focus on real challenges, the CBL framework

emphasizes contextualized and validated solutions

for real-life complex problems, something hard to

achieve with traditional educational hackathons that

are bound to a classroom context, subject-matter, and

narrow learning outcomes. A natural consequence of

this focus is that teams have to be multidisciplinary,

combining knowledge and expertise in the domain of

the big question (in CBL terms) and the technologies

relevant for the challenges.

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

672

Figure 1: The typical hackathon process, in terms of essential activities, stages, and supporting elements. Source: (Komssi

et al., 2015).

With over 200 students from two countries and

three different study programs participating (see Sec-

tion 5.1 for details), the event offered a unique

real-life learning opportunity since it was student-

organized. A dedicated group of students managed

the event logistics and served as project managers for

the hackathon teams, gaining hands-on experience in

both coordination and leadership. The organizational

structure behind this setup is discussed in the follow-

ing section.

5 CASE STUDY AND RESULTS

This section presents how the Hack4CBL frame-

work was used for the development of a binational

hackathon with challenges centered on the big idea of

tourism 4.0. Several iterations were conducted within

each step of the framework to refine results and move

to the next block.

5.1 Pre-Hackathon

While the hackathon stage receives the most attention,

the pre-hackathon stage does all the heavy-lifting

needed for the event to succeed. This stage is charged

with setting up the hackathon, scoping the challenges,

and doing the necessary team-building exercises prior

to the event. The participants also need to prepare for

the hackathon.

As mentioned earlier, the big idea of this

hackathon was the concept of Tourism 4.0. Digital

transformation has led the tourism sector to engage in

various innovations, giving rise to terms like Tourism

4.0 or Smart Tourism. Tourism 4.0 is defined as the

new tourism value ecosystem based on the high-tech

service production paradigm characterized by adopt-

ing the basic principles of Industry 4.0 (Pencarelli,

2020): interoperability, virtualization, decentraliza-

tion, service orientation, data analytics, and modular-

ity.

The concept of Tourism 4.0 focuses on the inten-

sive use of digital technologies, such as specialized

interactive systems; IoT; big data and data analytics;

artificial intelligence; blockchain; virtual, augmented,

and hybrid reality; among others. This approach has

driven full automation in the production and deliv-

ery of tourism goods and services, potentially caus-

ing technological disruptions in the sector (Ivanov,

2020). Digital technologies are not limited to basic

automation; they have the potential to reshape service

strategies and customer experiences, enhancing effi-

ciency, scalability, and reliability while enabling rapid

responses to customer needs (Zaki, 2019).

Following this big idea, it was decided to include

two countries in this hackathon: Colombia and Costa

Rica. These countries were selected because their

tourism sectors significantly contribute to the national

GDP–2.3% and 8%, respectively (UN Tourism, 2024;

Ort

´

ız-Pab

´

on et al., 2024)–and because they are in a

similar time zone and have no language or cultural

barriers. Finally, the university leading the hackathon

is located in Colombia.

A total of 210 undergraduate students from the

Pontificia Universidad Javeriana in Colombia and the

Instituto Tecnol

´

ogico de Costa Rica, Campus San

Carlos, participated in this hackathon. They were di-

vided into 27 interdisciplinary teams, with each team

From Big Idea to Prototype: A Challenge-Based Learning Framework for Hackathons in Higher Education

673

Figure 2: The Hack4CBL framework.

comprising six to seven members. The students rep-

resented various fields, including systems engineering

(Colombia), computer engineering (Costa Rica), busi-

ness administration (Colombia), tourism management

(Costa Rica), and data science (Colombia). Team for-

mation was overseen by a project management team

formed by students.

A panel of tourism industry professionals and en-

trepreneurs from both countries were charged with

coming up with the essential questions and a total of

17 specific challenges to tackle during the hackathon

stage. Each team selected the most attractive chal-

lenge, implying that some challenges were selected

by more than one team, while others were not selected

by any team.

Each team was provided with ample documen-

tation about tourism 4.0 for preparation, and a

workspace in Microsoft Teams for file management

and communication.

As preparation for the hackathon stage, teams in-

vested six weeks analyzing the tourism sector in gen-

eral, gaining specific knowledge about Tourism 4.0.

In this preparation, students developed skills for prob-

lem contextualization and alignment with the specif

socio-economic contexts of the tourism sectors in

Colombia and Costa Rica. This involved a combina-

tion of virtual and in-person modes. These were used

for teamwork, validations, and interactions with aca-

demics and tourism industry professionals from both

countries.

During this preparation, crucial support was pro-

vided to ensure the successful development of the

exercise. A space was created for interaction with

tourism industry experts (entrepreneurs, consultants,

and academics) through bi-weekly webinar sessions

in which teams were able to deepen their knowledge

of the tourism sector and integrate agile feedback into

their workflow. These bi-weekly webinar continued

into the hackathon stage. The interaction with experts

led to the emergence of a broad set of guiding ques-

tions, guiding activities, guiding resources, and the

drafting of solutions.

The logistics and technical provision aspects of

the project were handled by five teams of five stu-

dents, each responsible for project management and

coordination of different aspects of the hackathon.

They formed an organizational structure guided by

functional areas and roles (Figure 3). This respon-

sibility was assigned to a Strategic IT Management

class

1

, which was in charge of managing the project

called “Smart Tourism 4.0 Hackathon, Colombia –

Costa Rica.”

2

A parallel organizational structure was

replicated to oversee project management, which was

1

Strategic IT Management is a core course in the Sys-

tems Engineering program at the Pontificia Universidad

Javeriana. Two classes, each with 20 students, took the

course during the first semester of 2023; one class was re-

sponsible for project management, while the other focused

on overseeing the management.

2

https://ingenieria.javeriana.edu.co/hackathon

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

674

Figure 3: Organizational structure for the management of

the project.

responsible for monitoring the project, controlling

schedules, reviewing results, ensuring the quality of

documented evidence, and addressing team needs.

5.2 Hackathon

This stage lasted two months, which was longer than

typical hackathons, to allow for multiple iterations,

enough interaction with industry experts, and deeper

domain-specific learning. Additionally, since the

hackathon was conducted alongside other academic

duties, students required more time to integrate this

into their schedules without risking burnout or disen-

gagement.

The hackathon stage was divided into two parts.

The first part was dedicated to requirement definition,

while the second part focused on prototype design

(mockups), user validations, business modeling, and

the construction of the first two versions of Minimum

Viable Products (MVPs).

This stage began with the preliminary research

conducted by each participant team during the pre-

hackathon, which led to the contextualization of the

problem or family of problems related to the selected

challenge. From there, each team constructed its

own scenario, selected the necessary reference frame-

works, and chose the most appropriate tools and soft-

ware development frameworks. They also secured the

necessary application programming interfaces (APIs)

and prepared their collaborative work environment.

In this stage of the hackathon, the teams con-

ducted several iterations of design, development, and

validation of their MVPs, incorporating structured

feedback sessions from professors and industry ex-

perts to refine their solutions. This iterative process

led to continuous improvement of the MVPs and al-

lowed teams to adapt their approaches based on the

feedback received. This was done with a combination

of remote and in-person work sessions.

Each team created three MVP versions. Version

0.0 defined the problem context, introduced the ini-

tial business model, and prioritized solution require-

ments (both functional and non-functional). Version

1.0 included final functionalities, a validated business

model, and significant progress in design and devel-

opment. Version 2.0 delivered fully developed, tested

functionalities and additional validations, backed by

a business profile with revenue projections, market

analysis, and financial estimates.

5.3 Post-Hackathon

The final stage focused on presenting results, evalu-

ation, and delivering the MVPs in their 2.0 version.

Based on this 2.0 version of the MVP, participants

developed a short video (between three and five min-

utes) featuring a pitch and a short demo.

With these MVP versions and their respective doc-

umentary supports, the results were evaluated by a

panel of entrepreneurs from both countries. In two

rounds of evaluation, the entrepreneurs reviewed the

solutions and rendered their verdict on the best ones.

The first round selected the top 10 solutions that, in

the entrepreneurs’ judgment, best addressed the chal-

lenge they were tackling. The second round of eval-

uation was conducted through a simulated investment

process. Each evaluating entrepreneur was fictitiously

allocated $150,000, which they had to invest in three

of the solutions from the first round. Each evaluator

was required to invest the full amount in the propor-

tions they considered most appropriate. At the end of

the exercise, the three finalists with the highest invest-

ments were identified (first, second, and third place).

The results were published on the hackathon web-

site (https://ingenieria.javeriana.edu.co/hackathon),

which was created by the management team as

a communication tool and to track the project’s

progress. It also served as a platform for each team to

present themselves through a short video.

Regarding the transfer of results, a meeting was

scheduled to hold the award ceremony for the win-

ners, attended by entrepreneurs (Figure 4). In this set-

ting, the corresponding awards were presented, and

an interaction space was created between hackathon

teams and entrepreneurs, aimed at generating mecha-

nisms for continuing the development of the winning

ideas.

6 DISCUSSION

In this paper, we propose the Hack4CBL frame-

work for the development of hackathons as an edu-

cational strategy for multidisciplinary teams with di-

verse learning outcomes. This framework was illus-

trated with a case study of a bi-national hackthon

between Colombia and Costa Rica. The hackathon

served not only as a space for technological inno-

vation but also as a valuable pedagogical experi-

From Big Idea to Prototype: A Challenge-Based Learning Framework for Hackathons in Higher Education

675

Figure 4: Hackathon award ceremony.

ment in multidisciplinary challenge-based learning.

This aligns with prior research by (Adinda et al.,

2024), which highlights the benefits of educational

hackathons on collaboration skills and the influence

of student characteristics and team composition on

performance.

Throughout the hackathon development, we ob-

served that students not only developed technical

skills but also competencies in project management,

communication, and teamwork. This experience was

further enriched by interactions with industry experts,

who provided valuable and realistic feedback. The fo-

cus on creating functional minimum viable products

(MVPs) allowed students to experience the full cy-

cle of product development, from ideation to imple-

mentation and evaluation. Additionally, the organiza-

tional structure (run by students) emulated a corpo-

rate environment, adding another dimension of learn-

ing for those involved in this structure. These findings

are consistent with numerous studies that emphasize

how collaboration in the workplace enhances innova-

tion and successful outcomes (Granados and Pareja-

Eastaway, 2019; Fanousse et al., 2021; Rosell et al.,

2014). Similarly, Adinda et al. (Adinda et al., 2024)

observe that collaborative leadership within an orga-

nizational structure has a strong impact on collabora-

tive competency and performance.

The active participation of entrepreneurs in the

evaluation of projects and the opportunity to receive

simulated funding for their projects provided addi-

tional motivation and a real-world market experience.

However, our observations also revealed emotional

challenges faced by students during the hackathon,

notably frustration and difficulties that led to conflicts.

As Kazemitabar et al. (Kazemitabar et al., 2023)

highlight, these conflicts can be internal–relating to

personal deficiencies and teamwork incompetence–or

external–pertaining to task or team dynamics. Addi-

tionally, cultural dimensions, particularly in terms of

ways of thinking and solutions as proposed by Hu et

al. (Hu et al., 2022), can influence students’ commu-

nication, collaboration, and innovation. These find-

ings suggest a need to integrate more explicit instruc-

tional and collaborative guidance, especially for first-

year students.

In summary, the hackathon proved to be an effec-

tive tool for practical training and the strengthening of

soft skills in an academic context, with a positive im-

pact on students’ preparedness for entrepreneurship

environments or the labor market.

7 CONCLUSION

In this paper, we presented the Hack4CBL frame-

work, a hackathon developmnent framework for ed-

ucational purposes based con the CBL framework. A

case study of a bi-national hackathon between Colom-

bia and Costa Rica centered on tourism 4.0, and de-

veloped with the Hack4CBL framework, was also

presented.

As a mechanism for action that brings together

different stakeholders around the development of so-

lutions in an MVP format, hackathons help accelerate

students’ professional learning processes by achiev-

ing learning outcomes that closely align with the re-

alities they will encounter in their professional lives.

For students coming from digital disciplines (i.e., sys-

tems engineering, computer engineering, data sci-

ence), the main lesson on this regard is that technol-

ogy does not happen, nor is it developed, in isolation.

Students from other disciplines (i.e., business admin-

istration, tourism management) got a deeper under-

standing on how digital technology can impact their

respective fields. Furthermore, when combined with

CBL principles, hackathons are an effective pedagog-

ical strategy to tackle a wide range of learning out-

comes. This implies that, even while participating

in the same team, students can be pursuing differ-

ent learning outcomes with their participation in the

hackathon. This is an ideal context for multidisci-

plinary learning, one that is seldom achieved with

other pedagogical strategies.

While we highlight the immediate educational

benefits of hackathons in this paper, more work is

needed on their long-term effects through longitudinal

studies, focusing on their influence on participants’

professional trajectories and career development.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We sincerely thank all stakeholders–students, pro-

fessors, and industry experts–for their role in this

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

676

project’s success. Special thanks to Pontificia Univer-

sidad Javeriana (Colombia) and Instituto Tecnol

´

ogico

de Costa Rica for their support and to the student

organizers for their project management efforts. Fi-

nally, we acknowledge the contributions of the GPT-

4o LLM by OpenAI in the editing of the paper, which

assisted with grammar, spelling, and readability im-

provements, without any influence on the ideas, struc-

ture, or arguments presented here.

REFERENCES

Adinda, D., Gettliffe, N., and Mohib, N. (2024). Educa-

tional hackathon: preparing students for collaborative

competency. Educational Studies, pages 1–19.

Anslow, C., Brosz, J., Maurer, F., and Boyes, M. (2016).

Datathons: An Experience Report of Data Hackathons

for Data Science Education. In Proceedings of the

47th ACM Technical Symposium on Computing Sci-

ence Education, SIGCSE ’16, pages 615–620. Asso-

ciation for Computing Machinery.

Chanin, R., Sales, A., Santos, A., Pompermaier, L., and

Prikladnicki, R. (2018). A collaborative approach to

teaching software startups: findings from a study us-

ing challenge based learning. In CHASE ’18: Pro-

ceedings of the 11th International Workshop on Coop-

erative and Human Aspects of Software Engineering,

pages 9–12.

Conde, M. A., Rodr

´

ıguez-Sedano, F. J., Fern

´

andez-Llamas,

C., Gonc¸alves, J., Lima, J., and Garc

´

ıa-Pe

˜

nalvo, F. J.

(2021). Fostering STEAM through challenge-based

learning, robotics, and physical devices: A systematic

mapping literature review. Computer Applications in

Engineering Education, 29(1):46–65.

Doulougeri, K., Vermunt, J. D., Bombaerts, G., and Bots,

M. (2024). Challenge-based learning implementa-

tion in engineering education: A systematic liter-

ature review. Journal of Engineering Education,

113(4):1076–1106.

Fanousse, R. I., Nakandala, D., and Lan, Y.-C. (2021).

Reducing uncertainties in innovation projects through

intra-organisational collaboration: a systematic lit-

erature review. International Journal of Managing

Projects in Business, 14(6):1335–1358.

Granados, C. and Pareja-Eastaway, M. (2019). How do col-

laborative practices contribute to innovation in large

organisations? The case of hackathons. Innovation,

21(4):487–505.

Hu, H., Yu, G., Xiong, X., Guo, L., and Huang, J. (2022).

Cultural diversity and innovation: An empirical study

from dialect. Technology in Society, 69(101939):1–

10.

Ivanov, S. (2020). The impact of automation on tourism and

hospitality jobs. Information Technology & Tourism,

22(2):205–215.

Jamison, C. S. E., Fuher, J., Wang, A., and Huang-Saad,

A. (2022). Experiential learning implementation in

undergraduate engineering education: A systematic

search and review. European Journal of Engineering

Education, 47(6):1356–1379.

Kazemitabar, M., Lajoie, S. P., and Doleck, T. (2023).

Emotion regulation in teamwork during a challeng-

ing hackathon: Comparison of best and worst teams.

Journal of Computers in Education, 11(3):879–899.

Kolb, D. A. (1983). Experiential Learning: Experience as

the Source of Learning and Development. Prentice

Hall, 1st edition edition.

Komssi, M., Pichlis, D., Raatikainen, M., Kindstr

¨

om, K.,

and J

¨

arvinen, J. (2015). What are Hackathons for?

IEEE Software, 32(5):60–67.

Mart

´

ınez, M. and Crusat, X. (2017). Work in progress:

The innovation journey: A challenge-based learn-

ing methodology that introduces innovation and en-

trepreneurship in engineering through competition

and real-life challenges. In 2017 IEEE Global En-

gineering Education Conference (EDUCON), pages

39–43.

Nichols, M. H. and Karen, C. (2008). Challenge based

learning: Take action and make a difference. Tech-

nical report, Apple.

Nicolescu, B. (2014). Multidisciplinarity, Interdisciplinar-

ity, Indisciplinarity, and Transdisciplinarity: Similari-

ties and Differences. RCC Perspectives, (2):19–26.

Ort

´

ız-Pab

´

on, E., Fern

´

andez-Mora, L., Nova-Ar

´

evalo, N.,

and Gonz

´

alez, R. (2024). Desaf

´

ıos digitales: An

´

alisis

de la madurez digital de un cl

´

uster tur

´

ıstico en seis

cantones de alajuela, costa rica. Revista Ib

´

erica de

Sistemas e Tecnologias de Informac¸

˜

ao, e68:57–74.

Paganini, L. and Gama, K. (2020). Female participa-

tion in hackathons: A case study about gender is-

sues in application development marathons. IEEE Re-

vista Iberoamericana de Tecnologias del Aprendizaje,

15(4):326–335.

Pencarelli, T. (2020). The digital revolution in the travel and

tourism industry. Information Technology & Tourism,

22(3):455–476.

Porras, J., Khakurel, J., Ikonen, J., Happonen, A., Knutas,

A., Herala, A., and Dr

¨

ogehorn, O. (2018). Hackathons

in software engineering education: Lessons learned

from a decade of events. In Proceedings of the 2nd

International Workshop on Software Engineering Ed-

ucation for Millennials, SEEM ’18, pages 40–47. As-

sociation for Computing Machinery.

Rosell, B., Kumar, S., and Shepherd, J. (2014). Unleashing

innovation through internal hackathons. In 2014 IEEE

Innovations in Technology Conference, pages 1–8.

UN Tourism (2024). Un tourism data dashboar. Technical

report, UN Tourism.

Zaki, M. (2019). Digital transformation: harnessing digital

technologies for the next generation of services. Jour-

nal of Services Marketing, 33(4):429–435.

From Big Idea to Prototype: A Challenge-Based Learning Framework for Hackathons in Higher Education

677