Sweat Quantification During Electrodermal Analysis

Combining Paper-Based Microfluidics with Printable Electrodes:

Design and Materials

Batoul Hosseinzadeh

1a

, Sarah Tonello

1b

, Nicola Francesco Lopomo

2c

and Emilio Sardini

1d

1

Department of Information Engineering, University of Brescia, Via Branze, 38, Brescia, Italy

2

Department of Design, Politecnico di Milano, Via Giovanni Durando, 10, Milano, Italy

Keywords: Electrodermal Activity, Paper-Based Microfluidics, Printable Electrodes, Microfluidic Systems.

Abstract: Significant challenges in Electrodermal Activity (EDA) are represented by poor wearability of commercial

electrodes and imprecise differentiation between alterations in skin conductivity due to nervous system

activities or sweat secretion in response to other stimuli. In this light, we propose a device that combines

paper-based microfluidic with printable electrodes to monitor EDA and sweat rate/volume simultaneously.

This setup not only refines wearability by implementing flexible, skin-compatible materials but also improves

quantification accuracy by distinguishing between baseline EDA conductivity and actual sweat output

providing a higher perception of the physiological state by harmonized sweat and EDA data. The preliminary

analysis reported was performed in a laboratory environment aiming at two main objectives: i) optimize the

design of paper-microfluidics pattern ii) compare different printable inks to select the most suitable one to

minimize contact impedance and achieve a sensitivity comparable to standard EDA electrodes. Results

obtained suggested the use of thick teeth design of microfluidics geometry to reduce variability in

measurements and Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS) as an optimal

coating material to provide superior sensitivity (3.07 μS/μl) and repeatability (average Relative Standard

Deviation (RSD) of 15%,) with a linearity range of 0-50 µl range while preserving low contact impedance

and trustworthy signals.

1 INTRODUCTION

Wearable technologies have increasingly become

popular, above all, in healthcare, since they allow to

empower individuals by tracking their lifestyle and

physiological conditions, timely (Iqbal, Mahgoub,

Du, Leavitt, & Asghar, 2021). While most devices

monitor physiological responses, such as pulse rate

oxygen level or body temperature, new investigations

concentrate on some valuable digital markers like

Electrodermal Activity (EDA) as it represents an

important tool in behavioral medicine, fulfilling as a

biosignal for individual emotional response (both

state and trait properties) (Chung et al., 2019; Kuo,

Wu, & Wang, 2022); in fact, it directly tracks stress-

related events on body activities and supports the

definition of possible strategies to recover

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0002-8172

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7325-7988

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5795-2606

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8629-7316

psychosomatic conditions through biofeedback.

Accurate EDA quantification is thus a crucial

characteristic in developing wearable technology

applicable in healthcare and occupational fields

In fact, EDA represents an effective solution in

acquiring emotional and stress-related conditions,

since its measurements is strictly related to complex

physiological processes. In particular, physiological

excitation is managed by a regulating interplay

between the sympathetic and parasympathetic sectors

of the autonomic nervous system (ANS); while the

parasympathetic system preserve energy, the

sympathetic part raises, metabolisms to tackle

external provocation, enhancing heart rate, arterial

pressure, and sweat secretion (Stanković, Adamec,

Kostić, & Habek, 2021). Sympathetic fibrils enclose

eccrine sweat secretors and their activation leads to

Hosseinzadeh, B., Tonello, S., Lopomo, N. F. and Sardini, E.

Sweat Quantification During Electrodermal Analysis Combining Paper-Based Microfluidics with Printable Electrodes: Design and Materials.

DOI: 10.5220/0013235900003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 1, pages 65-73

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

65

sweat production; as sweat penetrates the ducts, it

generates low-resistance routes that amplify skin

conductivity, detectable as electrodermal activity.

EDA, therefore, represents sympathetic nervous

functions and performs as a sensitive signal for

alteration in excitement correlated to emotion,

cognition, and awareness.

Clinically, EDA is tracked with an EDA sensor

transcribes this conductivity alteration into analytical

data (W. Boucsein, 2012). Although EDA

measurement has proceeded during the past century,

most research has been restricted to short-term

observation in labs or distinct surroundings. There is an

increasing demand for wearable technologies to track

EDA over a long-term period, as they enable seamless

and non-invasive data collection during daily activities

(Kappeler-Setz, Gravenhorst, Schumm, Arnrich, &

Tröster, 2013). This extended observation can disclose

sympathetic nervous system patterns on a long-lived

scale rather than short-term measurement, revealing

states formerly unnoticeable. Additionally, monitoring

EDA in “natural” and ecological conditions provides a

more accurate and reliable understanding of

physiological status than measurements in artificial

settings (Posada-Quintero & Chon, 2020). However, a

main challenge for pleasant long-term EDA recording

is the limited accessibility of reliable and faithful

flexible sensors. In fact, EDA measurement needs two

electrodes, which must be placed on the user's skin;

anyhow, present commercial silver/silver chloride

(Ag/AgCl) electrodes are based on bulk materials and

thence inflexible, and depend on gels and powerful

adhesives, which can inhibit wearability, above all,

whenever specific conditions are under analysis (W.

Boucsein, 2012).

As wearable technology is growing, there are

rising demands for flexible electrodes, requesting

scalable manufacturing protocols (Zheng et al.,

2014). Flexible and stretchable EDA sensors can be

fabricated employing printed electrodes to present a

novel technique that improves both the efficiency and

convenience of wearable devices. Indeed, printed

electrodes can be fabricated on flexible, and light

substrates such as paper or polymers via scalable

approaches such as inkjet or screen printing, which

are economical and authorized for faithful patterning

(Pang, Lee, & Suh, 2013). With printed electrodes,

EDA sensors can be effectively integrated into

wearable tools, embedded into clothing, or attached

directly to the skin, providing continuous and

seamless tracking of emotional and stress-related

states in real-world conditions. Moreover, printed

electrodes promote higher sensitivity and versatility,

necessary for recording narrow alterations in skin

conductivity associated with stress and excitement.

This development not only expands the

implementation of EDA measurement in health and

behavioral research but also assists the development

of effective and user-friendly wearable technology.

Additionally, EDA sensors clinically encounter

some restrictions due to their inability to precisely

differentiate between alterations in skin conductivity

related either to true sweat secretion or other

environmental parameters. These variations result in

inherent variability in EDA monitoring, specifically

during long-term tests, where evaporation and weak

adherence influence signal trustworthiness (Cui &

Schlessinger, 2006). Incorporating a microfluidic

system overcomes these limitations by transferring

sweat continually to the electrodes, preserving

acceptable skin contact and minimizing dehydration-

related attenuation. On the other hand, microfluidic

channels, been fabricated for this purpose, could

allow to obtain also accurate sweat rate and volume

measurements, acquired in parallel to EDA data, thus

serving to distinguish between baseline conductance

alterations and real sweat events (Ullah et al., 2023).

While conventional microfluidic devices require

complicated lithographic operations, hydrophilic

porous channels like filter paper turned up as an easier

substitute; in fact, the paper-based apparatus utilizes

natural capillary movement to instantly take in and

transfer sweat, enabling them efficient for constant,

skin-compatible observation (Silva-Neto et al., 2023).

In this study, we propose a novel integrated

solution able to simultaneously track the electrodermal

activity and sweat rate employing a unified electrode

design. The sensor under development combines a

paper-based microfluidic system with printed

electrodes to monitor both EDA and sweat

rate/volume. This multi-functional action can provide

accurate measuring of skin conduction alteration while

steadily collecting and evaluating sweat along the

microfluidic layer. The paper-based absorptive layer

conducts sweat instantly from the skin to the

electrodes, enabling immediate measuring of sweat

secretion rate and volume. This setup not only refines

wearability through the implementation of flexible,

and skin-compatible materials but also improves

quantification accuracy by distinguishing between

baseline EDA conductivity and actual sweat output

providing a higher perception of the physiological state

by harmonized sweat and EDA data. In this picture, the

present contribute reports a preliminary analysis of the

design in term of paper-microfluidics geometry and of

printable materials to maximize flexibility and to

minimize contact impedance.

BIODEVICES 2025 - 18th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

66

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

The materials employed for preparing the paper-

based microfluidic sensor included: Whatman filter

paper (Grade 1), chosen for fast fluid transportation

of 150 sec/100 ml, Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)

polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS) and single-

walled Carbon nanotube (CNT); phosphate buffer

solution (PBS) (pH: 7.4); all these materials were

purchased from Sigma Aldrich company. The

disposable Ag/AgCl conductive hydrogel EDA

Electrodes were obtained from Cardinal Health

TM

.

Silver nanoparticles based aqueous ink (JS-A426)

was obtained from Novacentrix.

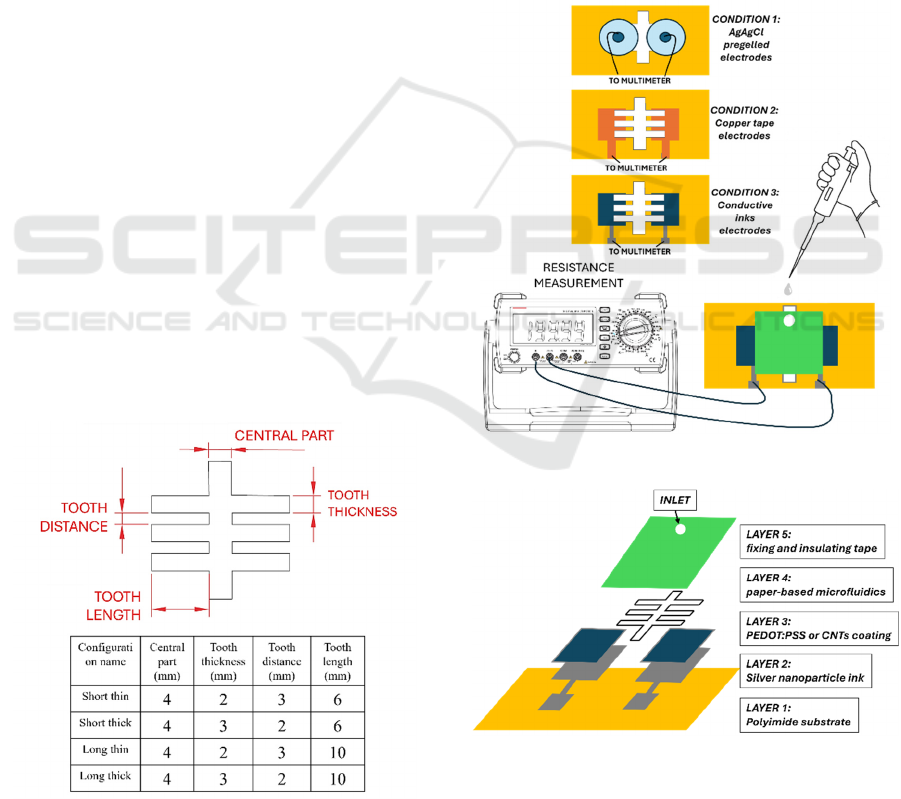

2.1 Layout Design

The geometry design of the microfluidic system is

important for effective sweat delivery and in line with

EDA signal recording. The patterns were designed

using a standard CAD software (Autocad) to

investigate the optimal route for fluid flow through

the Whatman paper by exploiting capillary action,

and to guarantee that liquid was delivered to the

electrodes without untimely dehydration. Each

structure concentrated on designing an adjusted,

small pathway to conduct liquid correctly from input

to the sensing electrodes. The branched pattern

structure was utilized to assess equal distribution,

which enhances the sensitivity and stability of the

signal. Thence, patterns in four different

configurations were designed, with dimensions of

central part, thickness tooth, distance, and length

tooth as detailed in figure 1.

Figure 1: Details of paper microfluidics patterns.

2.2 Laser-Cut Microfluidics Pattern

The preparation of the paper-based microfluidic

pattern was carried out by using a CO₂ laser cutting

system (FLUX Beambox instrument, 40 W laser and

1000 dpi resolution). Cutting parameters were

defined compatible with Whatman filter paper to

avoid extra heating buildup; specifically, the precise

defined designs were introduced into the cutter

software (Beam Studio) and critical parameters, such

as power, speed, and frequency, were attentively

calibrated to obtain clean, slight channels without

burning or damaging the paper edges. Eventually, a

medium power of 18 % of maximum output and a

mild cutting speed of 18 mm/s were set to keep the

paper’s structural unity and capillary features.

Figure 2: Experimental set up.

Figure 3: Detailed components of the devices combining

printed approach to realize EDA with microfluidics.

Sweat Quantification During Electrodermal Analysis Combining Paper-Based Microfluidics with Printable Electrodes: Design and Materials

67

2.3 Measurement Protocol

The protocol for characterizing electrodes exploited

the use of a controlled volume of a PBS solution to

induce measurable changes in the DC resistance,

from with changes in conductance can be then

calculated as the reciprocal of the values obtained.

The instrument employed to perform measurement

was a benchtop digital multimeter (6 1/2 digits,

Keysight) with a sampling rate of 2 Hz. This PBS

saline solution was selected to imitate sweat owing to

its comparable ionic constitution. The relation

between volume and resistance was obtained by

performing following standard addition of 10 µl

injected into the inlet part of the paper-based

microfluidic pattern. Three different types of

electrodes were compared. The traditional EDA

Ag/AgCl pre-gelled wet electrodes were examined

first to monitor their feedback to the conductive way

generated by the liquid (condition 1, fig. 2). Further,

two different configurations with dry electrodes were

tested: dry copper tape electrodes and dry electrodes

realized with different combinations of printable inks

(condition 2 and 3, fig. 2).

The copper electrodes, introduced as a first step to

simulate dry printed electrode configuration, were

obtained by cutting the conductive copper tape into

1.5 cm × 1.5 cm dimensions and located underneath

the paper-based microfluidic structure, setting up a

conductive medium for initial conduction measuring.

This copper-tape-based layout lets us evaluate a dry

electrode-based setup and improve the protocol.

A similar construction was assembled using the

printed electrode approach. A 1.5 cm × 1.5 cm area

was covered with a layer of silver ink to make a firm

and highly conductive foundation. To improve and

optimize signal sensitivity and reduce contact

impedance, a secondary conductive film was coated

on top of the silver base, made of either PEDOT:PSS

or CNT, materials well-known for their flexibility and

conductivity (figure 3). Every setup (copper tape,

Ag/PEDOT:PSS, and Ag/CNT was specifically

examined, by individually exploiting the same

procedure (figure 2). Variability and repeatability

ware evaluated by replicating the same measurements

in different conditions; repeatability, in particular,

was evaluated replicating each test for at least four

times for any electrode composition. Furthermore,

reproducibility was evaluated by preparing 3 identical

configurations for each material type and repeating

the test.

2.4 Data Analysis

Data obtained from each resistance measurement

against time were converted in conductivity values by

calculating the reciprocal of the DC resistance. After

that, data were filtered with a moving-average filter

(window of 20 samples), to remove high-frequency

noise before proceeding with the calculation of

metrological parameters. Further, median filters were

exploited to remove spikes due to external

interference during the following injections.

Conductivity values used to build the calibration

plot were sampled from the measured curve against

time exploiting a thresholding of the first derivative

of the signal. In detail, injection times were

recognized on the plot as the instants corresponding

to the values overcoming a defined threshold; the

threshold was adapted depending on the full-scale

range measured in each test. Once the injection times

were identified, sampling times were detected adding

30 s to each injection time, and the conductivity value

corresponding to that instant was sampled and

exploited to build the calibration curve. The 30 s

delay of the sampling time respect to the injection

time allow us to properly sample conductivity values

after that transient behavior occurring at every

injection. This transient instability observed for the

first seconds after each injection represents a well-

known challenge when coupling electrodes with

microfluidics (Arantes & Paixão, 2022; Lai, Lim,

Lee, & Huang, 2021) and it is due to the perturbation

of the complex interaction between paper-based

microfluidics surface and conductive electrodes

taking place when the newly injected liquid is filling

the porous microfluidics, thus they should not be

considered since in those instants the proportionality

between liquid volume and conductivity does not

appear well defined.

Sensitivity was calculated as the slope of the

calibration curve obtained by fitting the current

values corresponding to each concentration. Relative

Standard Deviation (RSD) was also calculated as the

ratio between the standard deviation and the average

value of repetitive measurements.

3 RESULTS

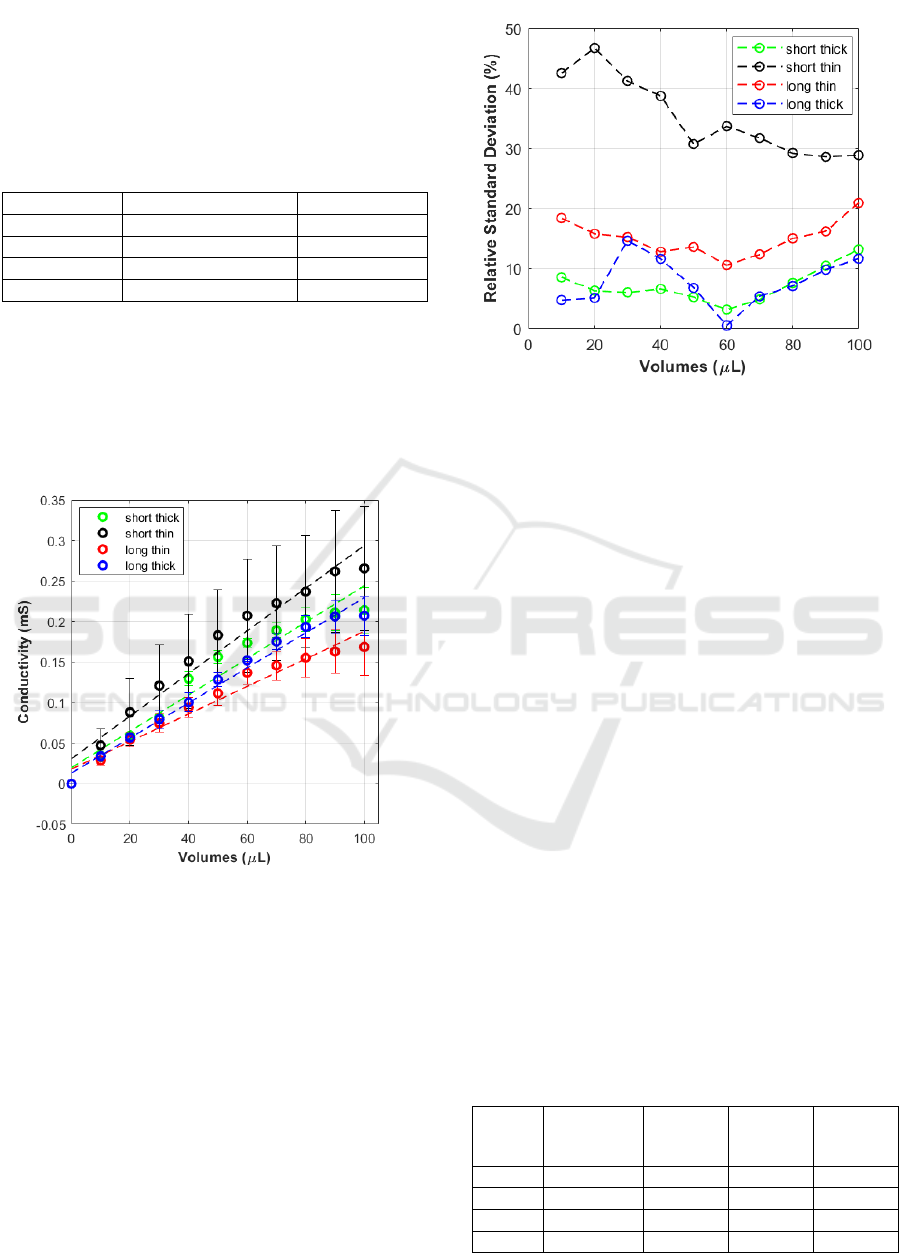

3.1 Geometries Comparison

Results obtained from experiments carried out using

wet electrodes to compare different geometries of the

laser-cut paper-based layouts showed no significant

differences in terms of sensitivities, as summarized in

BIODEVICES 2025 - 18th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

68

Table 1 and displayed graphically in figure 4. Thus,

despite the short-thin-teeth geometry showed the

highest average sensitivity, the high RSD associated

made this approach worst compared with other

geometries.

Table 1: Average sensitivities in μS/μL obtained for each

geometry, and corresponding RSD in %.

Geometr

y

Sensitivit

y

(

μ

S/

μ

l

)

Max RSD

(

%

)

Short Thin 2.629 46%

Long Thin 1.699 21%

Short Thic

k

2.241 13%

Lon

g

Thic

k

2.162 15%

Significant differences can be observed in terms

of variabilities. Thin-teeth geometries in particular

showed relative standard deviations higher than 30%

for short and 15% for long teeth. On the contrary,

thick teeth both long and short, showed comparable

variabilities, lower than 15% for all the volumes of

PBS tested (figure 5).

Figure 4: Comparison among calibration curves obtained

combining pre-gelled Ag-AgCl electrodes with different

paper-based laser cut designs.

This difference should probably be due to the most

stable contact area created between the pattern and

electrodes in the case of thicker than thinner teeth.

Further, the higher available surface provides an

increased absorption capacity during the different

steps. Considering these results, since lower RSD in

the studies indicates a higher reliable measurement

system, crucial for accurate process improvement,

thick teeth geometries were selected as the most

reliable for further tests.

Figure 5: Comparison among RSD obtained combining pre-

gelled AgAgCl electrodes with different paper-based laser

cut designs.

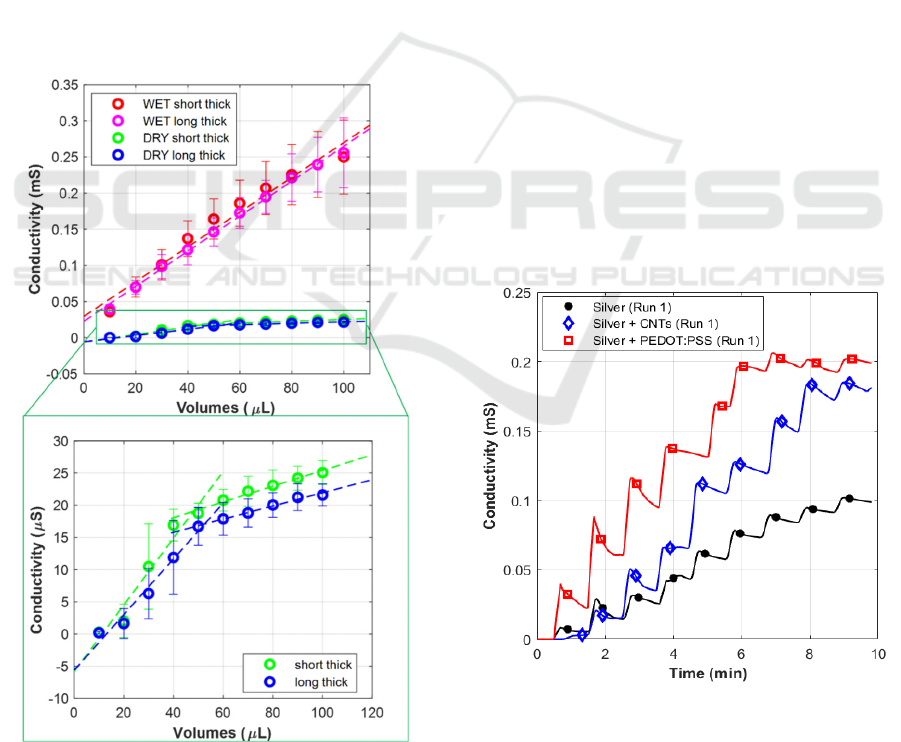

3.2 Wet and Dry Electrodes

Comparison

Significant differences can be observed comparing

the traditional pre-gelled wet electrodes in Ag/AgCl

with the dry copper electrodes, with no significant

differences between the geometry with long teeth and

the one with short teeth. The similarity observed

between long and short teeth represents an interesting

finding that provides the opportunity to adapt the

length of the teeth in future works targeting

simultaneous sweat volume and EDA measurements.

The teeth length can therefore be optimized

depending on the distance between the electrodes that

can ensure the most suitable EDA measurements.

Considering that, from literature, the most common

distances between EDA electrodes is between 10 and

20 mm, long teeth geometry appears as the most

promising and thus the experiments performed

employing printable inks were performed relying on

this geometry. Results obtained in terms of

sensitivities, linear ranges, and RSD are summarized

in Table 2 and graphically shown in figure 6.

Table 2: Average sensitivities in μS/μL obtained for the two

different electrode types (wet and dry), and corresponding

RSD in %.

Electrod

e type

Geometry Range

linearity

(

μ

l)

Sensitivity

(μS/μl)

Max RSD

(%)

WET Short Thic

k

0-100 2.403 21%

WET Lon

g

Thic

k

0-100 2.420 18%

DRY Short Thic

k

0-50 0.518 50%

DRY Long Thic

k

0-50 0.433 50%

Sweat Quantification During Electrodermal Analysis Combining Paper-Based Microfluidics with Printable Electrodes: Design and Materials

69

In particular, regarding the sensitivities, wet

electrodes showed an average sensitivity of

almost 5

fold respect to dry copper electrodes, in the range 0-

50 μl, and of almost 25-fold in the range 50-100 μl

where the dry electrodes showed a saturation

behaviour, with a sensitivity of 0.1 ± 0.01 μS/μl.

Regarding variability, the largest variability was

observed in the range 0-50 μl, where dry electrodes

showed RSD higher than 50%. This behaviour could

be related to a limited interface between the dry

electrode surface and the paper surface poorly soaked

in PBS. The RSD appears to decrease, reaching

values comparable with the wet-gelled electrodes for

volumes in the range 50-100 μl, where probably a

higher surface interaction is obtained due to the

increased soaking of the paper fluidics. Differently

from dry electrodes, wet electrodes showed similar

RSD (< 20 %) for all the volumes of PBS injected,

regardless of the range tested, confirming that the

gelled surfaces of the electrodes ensure a lower

contact impedance and a stable interface with the

Figure 6: Comparison among calibration curves obtained

employing wet and dry electrodes combined with thick-

teeth pattern geometries.

paper fluidics no matter the level of paper soaking.

The significant differences observed in this

comparison, in terms of both sensitivity and

variability, raise relevant discussion points regarding

the type of material that needs to be used to guarantee

low contact impedance and stable interface between

paper and electrode. Following several literature

evidence, the choice of the material was thus

addressed to nanomaterials and conductive polymers

(e.g. PEDOT:PSS) both well-known to improve

contact impedance issues traditionally emerging

when dealing with dry electrodes.

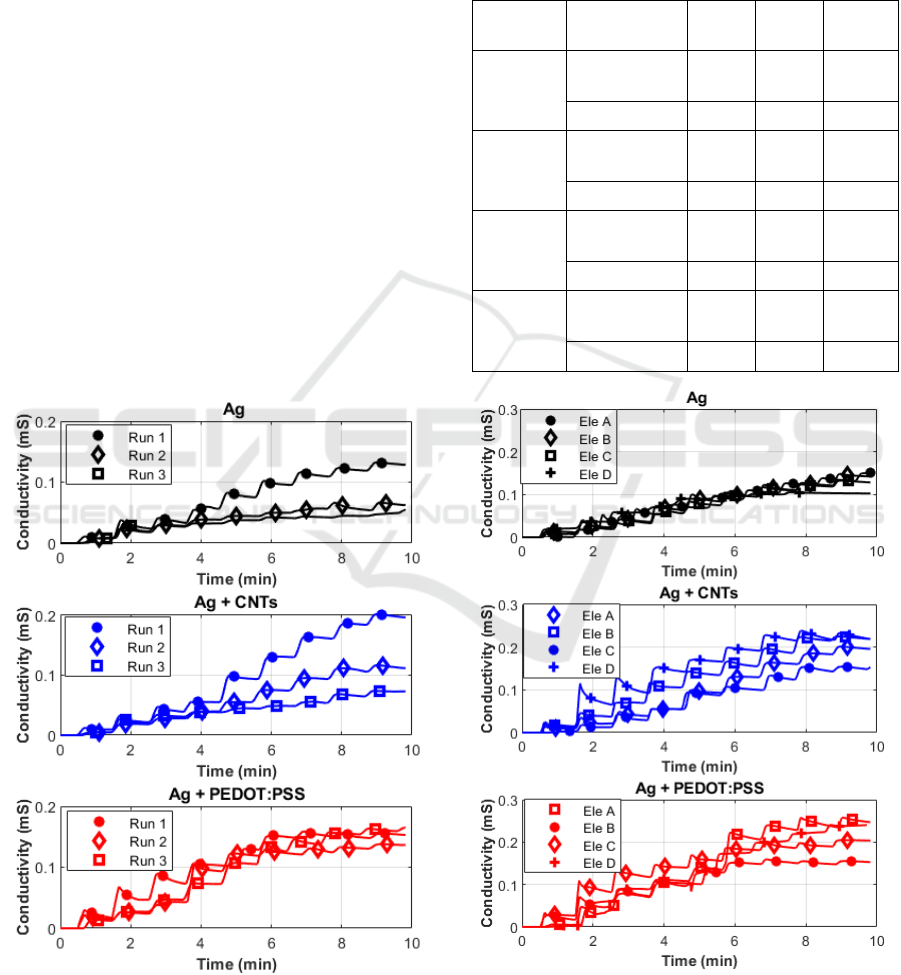

3.3 Ink Combinations Comparison

A significant increase in terms of sensitivity could be

obtained by relying on both CNT and PEDOT:PSS

coatings, with respect to bare silver electrodes, as it

can be observed from the comparison among the

measured curves reported in Figure 7. Examples of

measurements obtained during repeatability and

reproducibility tests are reported in Figures 8 and 9.

A summary of sensitivity and RSD in each single run

and the averaged values across different electrodes

(reproducibility test) and different repetitions of the

measurements on the same electrodes (repeatability

tests) can be summarized in Tables 3 and 4. Results

reported focus only on the range 0-50 μl to exclude

higher volume for which both CNTs and PEDOT:PSS

coated electrodes showed saturation.

Figure 7: Comparison among conductivity measurements

obtained combining long-thick-teeth pattern geometry with

three different combinations: silver, silver + CNTs, silver +

PEDOT:PSS.

BIODEVICES 2025 - 18th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

70

For all the conditions tested during the

repeatability test, measurements performed after the

first showed a decrease in sensitivity, consequent to

changes in the surface contact interface happening

after the first contact between PBS, paper, and

the conductive surface of the electrode. Electrodes

realized using silver coated with PEDOT:PSS

however showed a higher repeatability compared to

silver and silver coated with carbon nanotubes, with

an RSD ranging from 6 to 14 %. As a negative aspect,

as it can be observed from Figure 5, PEDOT:PSS

showed a smaller linearity range, with a saturation

after 50 μl. This result should be kept under

consideration especially if targeting applications with

high sweat rates; in this specific case, a solution might

be to employ a paper with a higher absorption

capacity to extend the linearity range of

measurements. Regarding the reproducibility test,

silver electrodes showed the best results, with RSD

lower than 10 %. The higher RSD obtained for coated

electrodes (<30% for CNTS and <22% for

PEDOT:PSS) can be explained by considering the

variability of the additional layer of ink deposited on

top of silver. Similarly to the measurements reported

for the repeatability test, even in Figure 6, it can be

Figure 8: Examples of repeatability tests on different ink

combinations: on each electrode couple the same

measurement was repeated three times.

appreciated that PEDOT:PSS performs better than the

other only in the range 0-50 μl, showing worse

reproducibility outside that range.

Table 3: Summary of the results from the repeatability test,

given as average sensitivities in μS/μl and RSD in %

obtained for each replicate of the electrodes (A, B, C, D) on

three repeated measurements on the same electrodes.

Electrodes

Metrological

characteristics

Ag

Ag +

CNTs

Ag +

PEDOT

ELE A

sensitivity

(μS/μl)

1.14 1.40 3.57

RSD % 56 41 6

ELE B

sensitivity

(μS/μl)

1.21 1.77 2.59

RSD % 53 67 9

ELE C

sensitivity

(μS/μl)

1.08 1.33 3.24

RSD % 54 58 5

ELE D

sensitivity

(μS/μl)

1.10 2.11 2.76

RSD % 53 74 14

Figure 9: Examples of reproducibility tests on different ink

combinations: the same measurement was performed on

four different replicates of electrode couples.

Sweat Quantification During Electrodermal Analysis Combining Paper-Based Microfluidics with Printable Electrodes: Design and Materials

71

Table 4: Summary of the results from the reproducibility

test, given as average sensitivities in μS/μl and RSD in %

obtained for each run on four different replicates of the

EDA conductive electrodes combined with microfluidic

path.

Run

Number

Metrological

characteristics

Ag

Ag +

CNTs

Ag +

PEDOT

RUN 1

sensitivity

(μS/μl)

1.82 2.80 3.07

RSD (%) 5 30 11

RUN 2

sensitivity

(μS/μl)

0.89 1.29 3.14

RSD (%) 8 25 16

RUN 3

sensitivity

(μS/μl)

0.68 0.87 2.91

RSD (%) 10 9 22

Overall, considering a trade-off among sensitivity,

repeatability, and reproducibility PEDOT:PSS appear

as the most suitable material to realize electrodes for

electrodermal activity combined with paper-based

microfluidics to monitor sweat volume. The

sensitivity obtained for PEDOT:PSS coated silver

electrodes, with an average of 3.07 μS/μl and an

average RSD of 15%, represents high promising

results if compared with the one obtained with

standard pre-gelled wet electrodes, with an average of

2.4 μS/μl and an average RSD of 20%.

4 CONCLUSIONS

This study focused on microfluidic pattern design and

electrode materials selection for EDA and sweat rate

monitoring and highlighted the need for performance

trade-offs. The thick-teeth geometry demonstrated

the most faithful structure for paper-based

microfluidics, certifying lower variability through

stable electrode contact. To reduce the gap between

wet and dry electrodes and surpass the limitations of

the dry electrode in terms of sensitivity and

consistency PEDOT:PSS electrodes provided better

results than the other studied materials since it

displayed superior sensitivity and repeatability within

the 0-50 µl range while preserving low-contact

impedance and trustworthy signals. Future works

may concentrate on the evaluation of different

printing techniques to realize the overall device and

on the enhancement of absorption volume to increase

linearity and establish powerful performance across a

wide range of various conditions (e.g. volume and

rate ranges).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was carried out within the MICS (Made in

Italy – Circular and Sustainable) Extended

Partnership and received funding from Next-

GenerationEU (Italian PNRR – M4 C2, Invest 1.3 –

D.D. 1551.11-10-2022, PE00000004 CUP

D73C22001250001).

REFERENCES

Arantes, I. V. S., & Paixão, T. R. L. C. (2022). Couple

batch-injection analysis and microfluidic paper-based

analytical device: A simple and disposable alternative

to conventional BIA apparatus. Talanta, 240, 123201.

doi:10.1016/j.talanta.2021.123201

Chung, H. U., Kim, B. H., Lee, J. Y., Lee, J., Xie, Z., Ibler,

E. M., … Rogers, J. A. (2019). Binodal, wireless

epidermal electronic systems with in-sensor analytics

for neonatal intensive care. Science, 363(6430).

doi:10.1126/science.aau0780

Cui, C.-Y., & Schlessinger, D. (2006). EDA Signaling and

Skin Appendage Development. Cell Cycle, 5(21),

2477–2483. doi:10.4161/cc.5.21.3403

Iqbal, S. M. A., Mahgoub, I., Du, E., Leavitt, M. A., &

Asghar, W. (2021). Advances in healthcare wearable

devices. Npj Flexible Electronics, 5(1), 9.

doi:10.1038/s41528-021-00107-x

Kappeler-Setz, C., Gravenhorst, F., Schumm, J., Arnrich,

B., & Tröster, G. (2013). Towards long term monitoring

of electrodermal activity in daily life. Personal and

Ubiquitous Computing, 17(2), 261–271.

doi:10.1007/s00779-011-0463-4

Kuo, W.-C., Wu, T.-C., & Wang, J.-S. (2022). Design and

Application of a Flexible Blood Oxygen Sensing Array

for Wearable Devices. Micromachines, 13(10), 1742.

doi:10.3390/mi13101742

Lai, Y.-H., Lim, J.-C., Lee, Y.-C., & Huang, J.-J. (2021).

Analysis of the Biochemical Reaction Status by Real-

Time Monitoring Molecular Diffusion Behaviors Using

a Transistor Biosensor Integrated with a Microfluidic

Channel. ACS Omega, 6(18), 11911–11917.

doi:10.1021/acsomega.1c00222

Pang, C., Lee, C., & Suh, K. (2013). Recent advances in

flexible sensors for wearable and implantable devices.

Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 130(3), 1429–

1441. doi:10.1002/app.39461

Posada-Quintero, H. F., & Chon, K. H. (2020). Innovations

in Electrodermal Activity Data Collection and Signal

Processing: A Systematic Review. Sensors, 20(2), 479.

doi:10.3390/s20020479

Silva-Neto, H. A., Arantes, I. V. S., Ferreira, A. L., do

Nascimento, G. H. M., Meloni, G. N., de Araujo, W. R.,

… Coltro, W. K. T. (2023). Recent advances on paper-

based microfluidic devices for bioanalysis. TrAC

Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 158, 116893.

doi:10.1016/j.trac.2022.116893

BIODEVICES 2025 - 18th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

72

Stanković, I., Adamec, I., Kostić, V., & Habek, M. (2021).

Autonomic nervous system—Anatomy, physiology,

biochemistry (pp. 1–17). doi:10.1016/bs.irmvd.2021

.07.006

Ullah, H., Shoaib, F., Zahid, S. D., Mahmood, M. I., Ali,

M., Ali, M., … Jafry, A. T. (2023). Design and

Fabrication of Digital Microfluidics device for Lab-on-

a-Chip Applications. In ICAME 2023 (p. 7). Basel

Switzerland: MDPI. doi:10.3390/engproc2023045007

W. Boucsein. (2012). Electrodermal Activity.

USA:Springer,.

Zheng, Y.-L., Ding, X.-R., Poon, C. C. Y., Lo, B. P. L.,

Zhang, H., Zhou, X.-L., … Zhang, Y.-T. (2014).

Unobtrusive Sensing and Wearable Devices for Health

Informatics. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical

Engineering, 61(5), 1538–1554. doi:10.1109/TBME.20

14.2309951

Sweat Quantification During Electrodermal Analysis Combining Paper-Based Microfluidics with Printable Electrodes: Design and Materials

73