Corporate Venturing in Sustainability Transition: Conceptual

Framework

Diana Smite

a

Faculty of Engineering Economics and Management, Riga Technical University, 6 Kalnciema Street, Riga, Latvia

Keywords: Sustainability Transition, Sustainable Corporate Venturing, Sustainability Transformation, Corporate

Entrepreneurship, Corporate Venturing.

Abstract: Corporate venturing serves as a bridge between the innovative potential of startups and the scale and resources

of established corporations. Corporate venturing has become an increasingly important mechanism for

facilitating sustainability transitions, but its unique attributes in the sustainability context are yet to be

adequately addressed. In response, this study seeks to fill this gap by proposing a conceptual framework that

emerges from an integrative literature review and qualitative content analysis of 42 scholarly articles. The

five primary themes that emerged as essential are innovation, ecosystems, partnerships/networks,

transition/transformation, shared value creation, and new business models. The proposed framework

contributes to the theoretical conversations around sustainable corporate venturing and offers practical

insights for practitioners seeking to integrate corporate strategies with sustainability objectives. This study

lays a foundation for future empirical and theoretical research by synthesizing fragmented perspectives and

offering structured guidance.

1 INTRODUCTION

The urgent need to achieve climate neutrality by 2050

and meet the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals

(SDGs) has placed significant pressure on

corporations to transform their operations.

Regulatory frameworks such as the European

Union’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive

(CSRD), launched in January 2024, aim to enhance

corporate transparency and accountability, expanding

sustainability reporting requirements to over 50,000

companies. The European Commission emphasizes

the urgent need for a fundamental economic

transformation, with EU companies seen as pivotal in

driving this shift toward achieving climate neutrality

by 2050 (European Commission, 2021).

Despite this, global business progress in the

transition to sustainability has been stagnant for the

past three years, according to the UN Sustainable

Development Solutions Network (2024). While

corporations recognize the potential competitive

advantage of integrating SDGs into their strategies

(United Nations Global Compact, 2023), many still

face considerable challenges. In the meantime, the

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-0565-5119

overall sustainability transition of the global economy

has been slower than planned due to its

unprecedented complexity (McKinsey Global

Institute, 2022).

Corporate venturing (CV), a form of corporate

entrepreneurship, has emerged as a critical

mechanism for enabling corporate sustainability

transitions. CV bridges startups' innovative potential

and established corporations' scale and resources,

allowing businesses to pursue sustainability goals

with greater agility (Mac Clay et al.; 2024; Kolte et

al., 2023a). Corporate Venture Capital (CVC)

programs are increasingly being employed, with

companies allocating 10-15% of their capital to

investments in sustainable businesses (Döll et al.,

2022). However, despite growing interest in CV,

there is still a lack of cohesive frameworks on how it

can be optimally leveraged to drive sustainability

transitions across different industries and

geographies. Namely, there is limited empirical

evidence on the influence of sustainability on CV

(Laibach et al., 2023) and little understanding of

sustainability transition-related challenges (Wunder

& Maula, 2024; Tandon et al., 2024). The literature

38

Smite, D.

Corporate Venturing in Sustainability Transition: Conceptual Framework.

DOI: 10.5220/0013240000003956

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business (FEMIB 2025), pages 38-50

ISBN: 978-989-758-748-1; ISSN: 2184-5891

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

presents a range of competing frameworks for

managing these transitions (Wunder & Maula, 2024;

Yström et al., 2021; Contini & Peruzzini, 2022),

leading to fragmented understanding and inconsistent

application across industries (Ghobakhloo et al.,

2021; Salomaa & Juhola, 2020; Lahti et al., 2018).

Thus, the problem lies in the fragmented

understanding of how CV can be effectively

leveraged to facilitate the transition to sustainability

within businesses. To fill the gap, the current research

poses the following questions:

Q1. What are the characteristics of corporate

venturing in the transition to sustainability?

Q2. How can these concepts be categorized

according to content analysis in a conceptual

framework?

The research aims to conduct a literature review

and employ qualitative content analysis, resulting in

a conceptual framework. The literature review

follows an integrative approach, following the

perspective of Kraus et al. (2022), that a literature

review should synthesize essential insights and

propose fresh narratives and conceptual frameworks

(Breslin & Gatrell, 2020; van der Waldt, 2020).

The remainder of the paper is structured as

follows: After the introduction, Section 2 presents the

research methodology. Section 3 provides insights

into the key theoretical concepts. Section 4 discusses

the results obtained from the content analysis. Section

5 provides an analysis of the conceptual framework.

Finally, Section 6 delivers a discussion with

implications for future studies.

The key contribution of this research is a

systematic overview of key concept categories related

to corporate venturing in the transition to

sustainability, resulting in a conceptual framework

and thus providing a twofold relevance. For scholars,

it identifies future research areas; for practitioners, it

provides an overview of a conceptual framework.

2 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Given the increasing relevance of sustainability

transition and CV, this study employed a literature

review and content analysis to examine the existing

scientific evidence concerning CV characteristics in

the corporate transition to sustainability. resulting in

a conceptual framework.

The initial data collection and screening were

processed in August - September 2024, using Scopus

and Web of Science databases. The search equation

for Scopus was (TITLE-ABS-KEY (corporate AND

ventur*) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (corporate AND

entrepreneurship) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY

(sustainab* AND transformation) OR TITLE-ABS-

KEY (sustainab* AND transition) ). For Web of

Science, advanced search was used with the equation

(corporate ventur* or corporate entrepreneurship)

AND (sustainab* transformation or sustainab*

transition). The search protocol resulted in 103

records from Scopus and 115 records from Web of

Science. Following the screening stage, 46 remaining

records were assessed for eligibility, resulting in the

outcome of 22 records. Additionally, 20 handpicked

records using the snowballing technique were added,

resulting in a final outcome of 42 thoroughly

researched records published between 2010 and 2024.

The article selection process and criteria are described

in Table 1:

Table 1: Summary of the article selection process.

Identification Screening Inclusion

Records

identified by

applying the

search equation

157 records

were screened

for title and

58 records

were excluded

In the abstract

screening, 54

records were

excluded as

non-relevant to

the scope of

the research

46 records were

assessed for

eligibility –

research and

review articles,

and conference

papers with full

text available,

published in

English, were

kept

Scopus: 103

Web of Science:

115

Non duplicated

records: 157

Outcome: 46 Outcome: 22

Snowballing: 20

Total: 42

The content analysis was performed based on

inductive technique (Mayring, 2000) with the

assistance of ATLAS.ti, a widely used CAQDAS

employed by researchers in different fields (Soratto et

al., 2020; Friese, 2019). By applying Atlas.ti, version

24.2.0.32043, the author employed an iterative,

inductive process for the qualitative analysis. The

process began with open coding, where initial codes

were created directly from the data. These initial

codes were grouped into broader categories. The

outcome was 11 key categories arising from 44 codes

applied toward 530 units of analysis. The coding

process is depicted in Table 2:

Finally, a conceptual framework was proposed,

following Jabareen's (2009); Breslin & Gatrell (2020);

Van der Waldt (2020) approach to building conceptual

frameworks. This approach involves creating a

network of interlinked concepts that jointly offer a

comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon.

Corporate Venturing in Sustainability Transition: Conceptual Framework

39

Table 2: Summary of content analysis.

Coding Revision and

Finalization of

the Coding

Frame

Summarization

and Interpretation

Inductive

coding process

Re-reading

coded segments

and finalizing

the category

system,

ensuring it

accurately

reflects the data

Summarizing

findings in each

category

Drawing insights

Outcome: 44

codes out of

530 units of

analysis

Outcome: 11

categories

Outcome:

Findings applied

to the conceptual

framework

3 THEORETICAL FOUNDATION

OF KEY CONCEPTS

3.1 Corporate Venturing

The academic literature lacks a unified definition of

CV, though it is commonly used as a broad term for

entrepreneurial activities within established firms

(Schuh et al., 2022). Gutmann (2019); Döll et al.

(2022) characterize CV as a set of corporate

mechanisms designed to accelerate innovation and

new business creation, while Tandon et al. (2024);

Schuh et al. (2023) describe the entire corporate

entrepreneurship as a means for companies to

reconfigure existing businesses.

Laibach et al. (2023) conclude that a lack of well-

established scientific definitions and blurred

boundaries between various types of CV results in a

scattered and fragmented body of research.

Kolte et al. (2023b) position CV as a part of the

Venture Capital (VC) sector, while Laibach et al.

(2023) state that CV's objectives differ from VC

funds. As such, CV investors are often less financially

driven, instead focusing on aligning investments with

corporate strategies (Bianchini & Croce, 2022;

Wunder & Maula, 2024). Whereas VC involves

minority stakes with minimal integration, corporate

involvement is much higher, peaking in joint ventures

and acquisitions (Dall et al., 2024). CV is more likely

to invest in green ventures, as corporations are more

ready to conform to future environmental regulations

and standards (Wunder & Maula, 2024). Green

ventures generally take longer to reach profitability

than other sectors (Mrkajic et al., 2019).

CV space is characterized by a growing

heterogeneity of CV modes such as corporate

accelerators, incubators, corporate venture capital,

strategic partnerships with startups, venture-client

model, market-based and science-based

collaborations, start-up cooperation programs,

venture building, hackathons, open innovation

contest platforms, joint ventures, acquisitions,

alliances and spin-offs (Gutmann, 2019; Schönwälder

& Weber, 2023a; Zucchella et al., 2023; Haarmann et

al., 2023, Doll et al., 2022). Although these activities

differ, distinguishing between them can be difficult

due to their overlapping features (Doll et al., 2022).

Corporations may also use multiple mechanisms

simultaneously to achieve diverse goals.

Accelerators are organizations, either for-profit or

non-profit, that operate within entrepreneurial

ecosystems to develop ventures over a short span of

time (de Klerk et al., 2024; Woolley & MacGregor,

2021). They provide funding, mentorship, training,

and office space with a cohort-based learning

experience (Gutmann et al., 2019; de Klerk et al.,

2024).

Incubators play a crucial role by assisting startups

in refining their business models and strategies while

offering essential resources and access to valuable

networks (Martins de Souza et al., 2024).

Under the venture client model, the start-up’s

solutions get integrated into the incumbent's products,

processes, or business models (Haarmann et al.,

2023). Similarly, Zucchella et al. (2023) point out that

the incumbent acts as a commercial partner and client

of startups. Corvello et al. (2023) describe the

collaboration between incumbents and start-ups to

form dynamic ecosystems for value creation.

Corporate venture capital (CVC) is widely

recognized as the largest and most influential form of

CV. Röhm et al. (2020) define CVC units as wholly-

owned subsidiaries of non-financial corporations that

invest in start-ups on behalf of their parent company.

Since the 1990s, the significance of CVC has

steadily grown across all sectors, including the

circular economy, becoming a major driver of global

innovation (Kolte et al., 2023; Benkraiem et al.,

2023). Research shows that CVC boosts market

valuation and patent production, and contributes

positively to both innovation and financial outcomes

(Ceccagnoli et al., 2018).

2023 global CVC funding totalled around $102.4

billion (CB Insights, 2023). Major global investment

areas included artificial intelligence, biotechnology,

and renewable energy, while Europe strongly emphasi-

zed healthcare and sustainability-driven innovations

(CB Insights, 2023). This reflects the growing

FEMIB 2025 - 7th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

40

importance of sustainability in shaping investment

decisions and strategies within the CVC landscape.

The literature is not unanimous in providing a

clear-cut concept of CV across dimensions such as its

locus, composition, expected outcome, and return. CV

activities can be categorized based on various

contextual dimensions, such as objectives, technology

and financial sources, and the degree of dependence on

the parent company (Schuh et al., 2022).

There is a distinction between internal and

external CV, which Reihlen et al. (2022) believe must

be studied separately. Internal CV refers to the

origination of innovations within the organization. In

contrast, external CV focuses on supporting ideas

originating outside the organization (Gutmann et al.,

2019), such as CVC, corporate accelerators, corporate

innovation labs, and direct corporate minority

investments in the external CV ecosystem. The

advantage of external focus lies in accessing external

resources more rapidly (Döll et al., 2022).

There is also a distinction between domestic and

international venturing based on the geographical

locations of new business activities (Shu et al., 2020).

Compared to domestic ventures, international

venturing provides access to larger markets.

Both private and state-owned companies engage

in CV. The reasons for investing differ between large

investors and small to medium businesses, and

between government-owned and privately owned

corporate investors (Hegeman & Sørheim, 2021).

PricewaterhouseCoopers (2022) position the

industry as the primary determinant of the intensity of

CV value creation. According to Hegeman &

Sørheim (2021), large government-owned energy

companies are active in CV. The energy sector is one

of the leading sectors in the sustainable

transformation undergoing rapid change (Zucchella

et al., 2023; Livieratos & Lepeniotis, 2017).

According to Livieratos & Lepeniotis (2017); Surana

et.al. (2023), the fourth wave of CVC came from the

IT and financial industries and traditional industries

like energy, fossil fuel, transportation and automotive

sectors. CV follows a similar pattern to private

independent venture capital, primarily investing in

sectors with expected short to medium-term returns,

such as fintech and software, while showing less

interest in long-term deep tech and traditional sectors

such as the air industry, chemistry, and construction

(Compaño et al., 2022). Over the past three decades,

global agricultural value chains have undergone

significant structural transformations (Mac Clay et

al., 2024; Fairbairn & Reisman, 2024). Agri-food

incumbents increasingly rely on startups for

innovative technologies to sustain their market

dominance (Fairbairn & Reisman, 2024). Hegeman

and Sørheim (2021) emphasize that companies are

more inclined to pursue corporate venture capital

when it is prevalent within their industry.

On the other hand, CV is no longer related solely

to a single sector or industry. Climate tech is an

example of how businesses use CVs to develop

cutting-edge technologies (Silicon Valley Bank,

2023) and confirms that corporates are exploring

avenues to address ESG goals. Recent trends in

manufacturing industries, such as digitalization and

sustainability, require companies to change their

products and processes (Schuh et al., 2023).

According to Kolte et al. (2023), the significance of

CV has been increasing in each sector to the extent of

becoming a major force of global innovation.

To demonstrate the rich CV scenery, the author

has summarized the CV modes in Figure 1:

Figure 1: Summary of CV modes (source: author’s created).

Corporate Venturing in Sustainability Transition: Conceptual Framework

41

Mutually beneficial collaboration between a

startup and an incumbent in CV occurs when the

incumbent seeks to drive innovation, increase agility,

or pursue a transformation while the startup gains

access to funding and support (Corvello et al., 2023;

Zucchella et al., 2023; Schuh et al., 2022). This

approach is a low-risk strategy for incumbents to

diversify their product portfolios by exploring new,

potentially profitable areas while leveraging their

competitive advantages (Urbano et al., 2022;

Compaño et al., 2022). Through alliance experience

and investment intensity, incumbents often

supplement a startup’s R&D efforts, with startups

driving early-stage discoveries and incumbents

scaling these innovations to mass markets (Lin, 2020;

Mac Clay et al., 2024).

Startups benefit from the incumbents' social and

material infrastructure, product expertise, proof-of-

concept validation, manufacturing capacity, legal

support, design, branding, established distribution

channels, and customer networks (Fairbairn &

Reisman, 2024; Zucchella et al., 2023). Corporations

gain new solutions to enter new markets, access

innovation, shift corporate culture, build startup

ecosystems, and gain insights into industry trends

(PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2022; Shin & Cho, 2020).

As a collaborative tool, CV is positioned as a more

efficient alternative to research-based spin-offs,

covering disciplines from product marketing to

management (Bendig et al., 2022a) while enhancing

incumbents' innovation efforts (Gutmann et al., 2019;

Zucchella et al., 2023). Additionally, CV accelerates

skill-building and resource acquisition, supported by

incumbents’ policies, infrastructure, industry

expertise, and technical assistance - contributing to

reduced costs and faster time-to-market for startups

(Shakeel & Juszczyk, 2019; Zucchella et al., 2023;

Kolte et al., 2023).

Effective CV depends on a strong fit between the

incumbent and the startup, expressed by trust,

commitment, shared enthusiasm, and professionalism

(Laibach et al., 2023). The incumbent’s reputation

and extensive customer base in both local and global

markets provide startups with new growth

opportunities, especially when products align with the

incumbent's long-term vision and add unique value

and growth prospects (Zucchella et al., 2023; Laibach

et al., 2023; Kolte et al., 2023). Several key principles

underlie successful venturing across industries: clear

goals, long-term commitment, alignment with core

business, operational autonomy, and achieving

critical mass (Livieratos & Lepeniotis, 2017).

Less successful CV is present when lacking a

clear strategy and objectives, encountering power

asymmetry, cultural clashes, or misaligned timelines,

as well as when startups collaborate with incumbents'

competitors (Jeon & Maula, 2022; Zucchella et al.,

2023; Leiting, 2020; Livieratos & Lepeniotis, 2017).

The complexity of CV investments further underlines

the need for a well-defined investment strategy

(Hegeman & Sørheim, 2021; Jeon & Maula, 2022).

To conclude, CV is a large space with diverse

mechanisms and modes across an increasing number

of industries. The blurred boundaries between CV

and traditional venture capital and its heterogeneity in

modes result in ongoing scientific research.

3.2 Sustainability Transition

Corporate sustainability has become a buzzword,

widely used across industries to signal a company's

commitment to transform its operations sustainably.

Sustainable corporate entrepreneurship, in particular,

is vital in driving economic growth under the

increasing climate change (Yasir et al., 2023), and

organizations must reconfigure their capabilities and

processes to achieve simultaneous economic returns

(Tandon et al., 2024).

However, the broad and sometimes ambiguous

usage of sustainability-related terms has diluted its

meaning. Without a universally accepted definition of

corporate sustainability, there is a need for a shared

understanding of sustainability criteria (Provasnek et

al., 2017).

Large companies are increasingly turning to CV

as a tool to contribute to the sustainability transition

(Hegeman & Sørheim, 2021). This approach is

crucial for companies transitioning to a

“sustainability upgrade” across their products,

processes, and organizational structures while

maintaining their competitive market positions

(Schaltegger et al., 2016).

Sustainability transitions are systemic and

complex, requiring the participation of a wide range

of stakeholders in a collaborative way (Ystrom et al.,

2021). The system perspective approach

acknowledges that sustainability challenges are

complex, interconnected, and span multiple scales

and actors. Sustainability transition entails

embedding environmental, social, and economic

objectives into an organization's core (Boons et al.,

2013). Sustainability transitions are non-linear

processes of systemic change (Loorbach et al., 2017)

demanding significant investments and the formation

of new partnerships and capabilities (Tandon et al.,

2024).

Given the complex and multidimensional nature

of the sustainability concept, the author identified the

FEMIB 2025 - 7th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

42

sustainability transition as the most suitable angle to

explore sustainable CV and effectively address the

research objectives.

4 CONTENT ANALYSIS

The 42 academic articles retrieved from the literature

review were used for the qualitative content analysis,

producing 530 units of analysis.

The units of analysis were then organized into 44

codes and consequently grouped into 11 categories

(see Table 3). The table provides an overview of

categories, descriptions based on established

definitions, an absolute count of codes per category,

and a relative frequency weight:

Table 3: Overview of categories (author’s created).

Category Description Count (n),

frequency

(%)

Innovation

Developing and

implementing new

products, solutions and

processes

146, 28

Ecosystems,

Partnerships and

Networks

Interconnected sectors,

organizations,

individuals, and

resources that interact

and co-evolve

98, 18

Transformation

and Transition

A fundamental or

evolutionary change in

a company's

operations, structure,

culture, or strategy to

improve performance

and adapt to emerging

market trends

64, 12

Shared Value Creating business

value by addressing

social, environmental

and economic matters

of the entire society

64, 12

New Business

Models

A new business model

is an innovative way to

create, deliver, and

capture value that

challenges traditional

practices

35, 7

Knowledge

Transfer

Sharing the individual

or collective

knowledge, skills, and

expertise from one

entity to another

32, 8

Financial

Returns

Monetary gains or

losses that an

investment or business

operation generates

over a certain period

27, 5

Culture and

Reputation

Certain organization’s

shared values, beliefs,

and norms resulting in

a company’s reputation

25, 5

Competitive

Advantage

The ability to

outperform the

organization’s

competitors by

offering distinctive

value to its customers

22, 4

Patents A government-granted

legal right that gives an

inventor exclusive

rights to make, use,

and sell their invention

for a set period in

return for publicly

disclosing the

invention

13, 2

Strategic

Renewal

Refreshing the

organization’s

operations through

strategies, capabilities,

and resources

6, 1

Among the 11 identified categories, Innovation,

Ecosystems, Partnerships, and Networks, and

Transformation and Transition emerged as the top

three, comprising 60% of the total weight.

Innovation, the most prominent category at 28%,

includes 13 codes ranging from broad innovation

concepts like new technologies, product, and process

innovations to specific sustainable innovation types

such as cleantech, eco, green, and environmental

innovation. Ecosystems, Partnerships, and Networks,

representing 18%, encompass 7 codes highlighting

collaboration among various actors within a system-

level, multilevel perspective, emphasizing a

shareholder-oriented approach. Transformation and

Transition, the third largest category at 12%, includes

4 distinct codes focused on transformations and

transitions at local, industry-wide, and global scales.

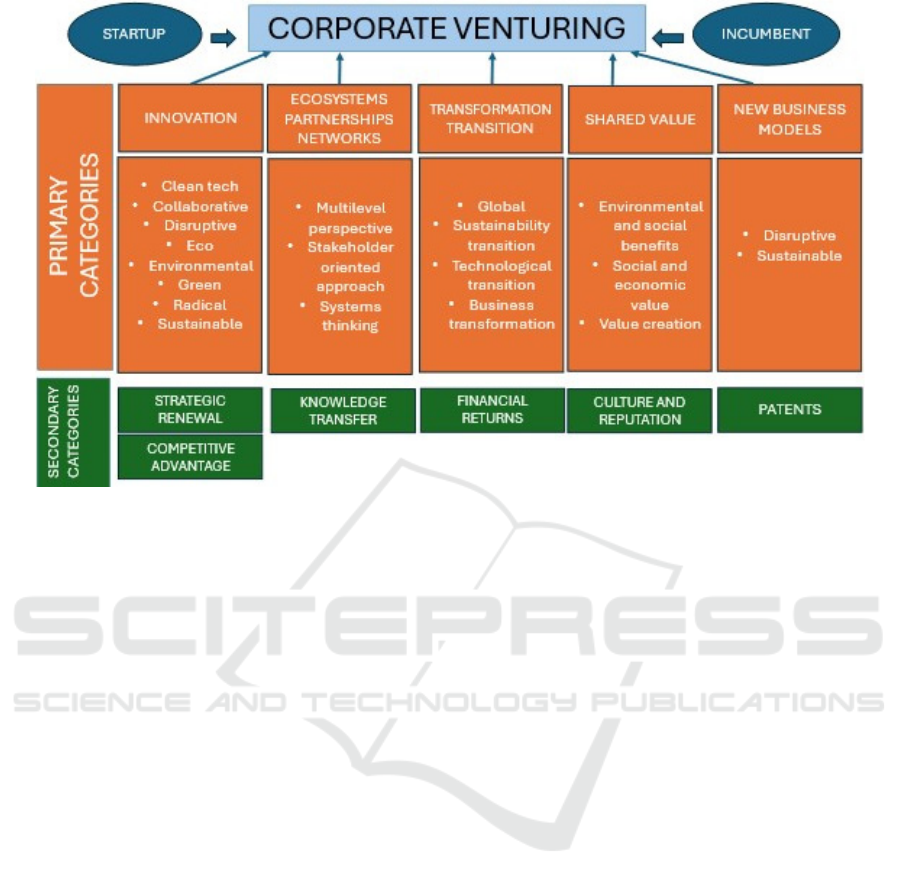

5 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

This section provides a detailed analysis of the

conceptual framework following the guidelines for

designing conceptual frameworks (Breslin & Gatrell,

2020; Van der Waldt, 2020; Jabareen, 2009). The

Corporate Venturing in Sustainability Transition: Conceptual Framework

43

proposed framework captures key features of CV in

its transition to sustainability and outlines primary

and secondary categories (Figure 3). Primary

categories represent fundamental elements of a

sustainability-focused CV, while secondary

categories may vary in presence and combination.

The framework suggests that CV transitioning to

sustainability is defined by its emphasis on

innovation, partnership networks and ecosystems,

transformative and transitional perspective, shared

value creation, and adopting new business models.

Innovation.

Innovation in the context of a sustainable CV exhibits

broad interpretation and characteristics.

Provasnek et al. (2017) call innovations as

changes introduced to the market that can be new,

incremental, radical, or disruptive.

CV provides access to the latest technologies from

AI, climate tech, and robotics (Silicon Valley Bank,

2023). Many incumbents are unfit to create radical

innovation since their capacity is optimized for

incremental innovations (Schuh et al., 2023). Reuter

and Krauspe (2023) consider CV a lever for corporate

innovation, while Kolte et al. (2023) call it a means

for incumbents to innovate in highly volatile

conditions. CV may also merge the capabilities of the

incumbent research units with those of their funded

start-ups (Benkraiem et al., 2023) or serve as an open

innovation platform (Pinkow & Iversen, 2020).

As the innovation hubs, CV are expected to

deliver radical innovations (Schuh et al., 2023) and

enhance company awareness of such trends as

sustainable and digital technologies

(PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2022; Laibach et al.,

2023).

Hockerts & Wüstenhagen (2010) and Bendig et al.

(2022) refer to green innovation as one of the key

factors in achieving a green transition. Green

innovation encompasses developing products,

services, and processes that support sustainable

development, often measured by the number of green

patents (Karimi Takalo et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2023;

Li, 2022). The study by Benkraiem et al. (2023)

indicates that incumbents are financially incentivized

to support green innovation while Wunder & Maula

(2024) note strategic objectives and dedicated focus

on sustainability as key drivers. In terms of

transformative innovations, different green

innovation types such as green energy and eco-

innovations in the renewable energy sector (Hegeman

& Sørheim, 2021; Provasnek et al., 2017); bio-based

and sustainable technologies (Laibach et al., 2023),

cleaner technologies to reduce GHG emissions

(Benkraiem et al., 2023) come up. Benkraiem et al.

(2023) attribute green innovation to radical

innovations, and Jing & Zhang (2023); Hegeman &

Sørheim (2021) position it as the means to achieve

sustainable growth and gain access to innovative

clean technologies.

The term "cleantech" is now widely recognized as

a significant investment category characterized by its

public good nature (Bianchini & Croce, 2022).

Radical cleantech, such as new energy technologies,

demands substantial capital in product development

and commercialization and long lead times

(Michelfelder et al., 2022; Hegeman & Sørheim,

2021; Benkraiem et al., 2023). Consequently, startups

need the financial investment coming out of CV, and

Mäkitie (2020) points out the significance of the vast

resources of established firms to potentially

accelerate sustainability transitions.

Sometimes innovations coming out of CV can

result in sustainable mass market transformation

(Hübel et al., 2022), described as radical

sustainability innovations (Olteanu & Fichter, 2022)

and transformative innovations (Hörisch, 2018),

while often they are just niche innovations

(Schönwälder & Weber, 2023). One of the reasons for

that is related to ownership rights, as startups often

maintain ownership of their product or service

(Zucchella et al., 2023). However, on occasion, small

isolated innovations can result in indirect

transformative influence on mass markets, such as

business model replication by other players in the

market (Schaltegger et al., 2016).

Ecosystems, Partnerships and Networks.

The reconfiguration of the incumbent’s capabilities

and processes to concurrently achieve economic

returns and social and environmental value requires

the development of new partnerships and capabilities

(Tandon et al., 2024). Effectively, it results in a long-

term structural change within the stakeholder setup

and networks. They can even involve the

coevolutionary interaction between competitors in a

market (Schaltegger et al., 2016) and actor

constellations for the coevolution of the business

environment (Stöhr & Herzig, 2022). Hörisch (2018)

emphasizes that forming multiple alliances and

partnerships increases the incumbent’s likelihood of

finding matching sustainability partners.

Sustainability requires changes across different

ecosystems. According to Leiting (2020), ecosystems

vary in size and can be interconnected or nested in

larger meta-ecosystems. However, collaboration with

FEMIB 2025 - 7th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

44

stakeholders in these ecosystems can present

significant challenges. Tandon et al. (2024) note

diverse interpretations of sustainability transitions

due to disparate goals. On the one hand, sustainability

being cross-functional brings different actors together

to generate profitable ideas (Dhanda & Shrotryia,

2021); on the other hand, they need to align on joint

and shared measurements and metrics. Di Vaio et al.

(2022) believe that sustainability transition is

effective when the perspectives of both internal and

external stakeholders are aligned. The government as

a stakeholder can get involved through a regulatory

framework such as policies, carbon credit markets

subsidies, and feed-in tariffs (Hegeman & Sørheim,

2021). A study by Westman et al. (2022) revealed that

sustainable entrepreneurs encounter significant

constraints when trying to contribute individually to

sustainability transitions; hence, the role of

partnerships and ecosystems is notable.

Transition and Transformation

Over the last few years, CV has become an enabler of

sustainability transformation, with 57% of all newly

founded European companies in the consumer goods

sector being green startups (Sheppard et al., 2023).

The growing focus on ESG issues is transforming

global business, making sustainability a critical

priority and a competitive advantage (Martins de

Souza et al., 2024). Sustainability transformation

refers to a systemic change within a company

resulting in sustainable business models, effective

sustainability measures, and ecological and socially

sustainable markets (Schaltegger et al., 2023;

Dijkstra-Silva et al., 2022); thus, being a holistic and

stakeholder-driven approach. The interaction

between startups and incumbents drives industry

sustainability transformations (Hockerts &

Wüstenhagen, 2010).

Sustainability transitions offer strategic

opportunities for businesses (Schaltegger et al.,

2023). CV plays a significant role in this transition

and acts as a catalyst to improve environmental

performance and pursue green innovation as part of

incumbents’ corporate performance strategies and

incumbents’ strategic renewal (Benkraiem et al.,

2023; Laibach et al., 2023; Yang, 2019; Shin & Cho,

2020; Tandon et al., 2024).

Shared Value

The hyper-transformation requires the entire business

world to restructure its way of working (Dhanda &

Shrotryia, 2021). According to Schaltegger et al.

(2016), a business that contributes to sustainable

development must create value for all stakeholders.

As a result, companies pursuing sustainable

models must account for a broader range of values

and stakeholder interests (Magnusson & Werner,

2023).

Various studies show that CV has the prevalence

of strategic objectives over financial ones, which seek

to generate measurable social or environmental

impact or shared value (Döll et al., 2022; Laibach et

al., 2023; Kolte et al., 2023). This dual focus is a new

business value creation paradigm. CV programs

allow the achievement of sustainability-related

objectives either voluntarily or imposed by legislation

(Battisti et al., 2022). However, Di Vaio et al. (2022)

consider the sustainable enterprise's intention to

create long-term social impact to be the key factor.

Tandon et al. (2024) stress the importance of

integrating sustainability into a firm's core strategy,

as delivering shared value also improves incumbents'

image and reputation (Gutmann et al., 2019; Kolte et

al., 2023).

New Business Models

Laibach et al. (2023) claim new disruptive business

models to improve the incumbent’s capabilities,

while Dhanda & Shrotryia (2021) note a fundamental

shift from traditional business models to new ones.

A sustainable business model contains the

company's sustainable value proposition to

stakeholders and generates, distributes and captures

economic value while preserving or regenerating

natural, social, and economic capital (Schaltegger et

al., 2016; di Vaio et al., 2022), addresses the needs of

all stakeholders and integrates both systems-level and

firm-level perspectives (Dhanda & Shrotryia, 2021)

and has a long-term horizon (Geissdoerfer, 2019).

According to Neumeyer & Santos (2018) its

development requires a supportive entrepreneurial

ecosystem due to its complexity. The circular

business model is somewhat similar and is designed

to create and capture value under an ideal resource

usage state (Lahti et al., 2018). George &

Schillebeeckx (2022) consider the development of

circular and regenerative business models as an

economic value multiplier.

Corporate Venturing in Sustainability Transition: Conceptual Framework

45

Figure 2: Summary of CV modes (source: author’s created).

6 CONCLUSIONS AND

IMPLICATIONS FOR FUTURE

STUDIES

This study analyzed 42 articles on sustainable

corporate venturing, identifying key concepts in the

literature, providing categorization and a conceptual

framework. The framework suggests that CV

transitioning to sustainability is defined by its

emphasis on innovation, partnership networks and

ecosystems, transformative and transitional

perspective, shared value creation, and the adoption

of new business models. The five key categories can

be claimed as “compulsory” categories of a

sustainable CV. The remaining 6 categories can

supplement key categories in different combinations

and weights. This framework fills a key gap in the

literature by systematically categorizing the core and

supplementary aspects of sustainable corporate

venturing. These elements complement and broaden

the systemic approach to sustainability transitions,

highlighting interconnectedness and collaboration

across multiple stakeholders.

Each of the five key categories is more

dimensional and complex than those typical of a

conventional CV.

Under the innovation category, next to generic

product and process innovation, radical, disruptive,

and transformative innovations impact entire

industries and create new ones.

Sustainable CV differs from conventional

ventures in forming more complex networks, aligning

stakeholders from competitors to social

organizations, and fostering collaborative ecosystems

to achieve long-term sustainability impact.

A meaningful sustainability transition can happen

at the meso and macro levels. CV emerges as a

significant catalyst in this transformation, shifting

broader ecosystems such as industries, consumer

societies, supply chains, and regulatory frameworks

towards sustainable development.

Shared value has become a new business value-

creation paradigm and is paramount to repositioning

companies as responsible players in the market. Thus,

they can meet evolving regulatory and societal

expectations and ensure the lasting success of their

businesses.

Finally, new business models focusing on

sustainability represent both an ethical obligation and

a strategic necessity for modern corporations.

This framework provides practitioners with a

practical guide for leveraging CV to drive

sustainability transitions. Organizations can apply

this framework to assess and refine their CV

strategies, ensuring they align with long-term

sustainability objectives.

Future research could validate the proposed

conceptual framework to confirm its relevance

FEMIB 2025 - 7th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

46

beyond the researcher’s perspective. Employment of

longitudinal analysis across diverse industries could

assess how the identified framework categories

evolve over time and influence various sustainability

metrics. Additionally, comparative studies across

different corporate sectors and geographical regions

could provide insights into contextual variations.

Finally, investigating the interdependencies between

these categories and other organizational factors, such

as leadership, could offer a more comprehensive view

of the mechanisms driving successful sustainability-

oriented transition enabled by CV.

While the research offers a thorough

understanding of a sustainable CV framework, some

limitations exist. First, the study was limited to

English-language articles indexed in Scopus and Web

of Science, potentially overlooking relevant research

in other languages or databases. Second, the analysis

focused on studies from 2010 onwards, which might

have missed important historical research. Third,

relying on qualitative methods may limit the

generalizability of findings to other contexts. Next,

the content analysis carries inherent subjectivity that

could influence the analysis. Lastly, the conceptual

framework possesses a subjective interpretation by

the researcher and lacks empirical evidence.

In conclusion, this research highlights the

importance of adopting a sustainable CV as a

potential strategic approach to achieving corporate

sustainability goals. By connecting innovative

startups with established companies, CV can drive

industry-wide shifts toward sustainable practices,

supporting global efforts to combat climate change.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Supported by the EU RRF within project No

5.2.1.1.i.0/2/24/I/CFLA/003 academic career

doctoral grant, ID 1036.

REFERENCES

Battisti, E., Nirino, N., Leonidou, E., & Thrassou, A. (2022).

Corporate venture capital and CSR performance: An

extended resource based view’s perspective. Journal of

Business Research, 139, 1058–1066. https://doi.org/

10.1016/J.JBUSRES.2021.10.054

Bendig, D., Kleine-Stegemann, L., Schulz, C., & Eckardt, D.

(2022b). The effect of green startup investments on

incumbents’ green innovation output. Journal of Cleaner

Production, 376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.1

34316

Benkraiem, R., Dubocage, E., Lelong, Y., & Shuwaikh, F.

(2023). The effects of environmental performance and

green innovation on corporate venture capital. Ecological

Economics, 210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.20

23.107860

Bianchini, R., & Croce, A. (2022). The Role of

Environmental Policies in Promoting Venture Capital

Investments in Cleantech Companies. https://doi.org/

10.1561/114.00000024_app

Boons, F., Montalvo, C., Quist, J., & Wagner, M. (2013).

Sustainable innovation, business models and economic

performance: An overview. Journal of Cleaner

Production, 45, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.20

12.08.013

Breslin, D., & Gatrell, C. (2023). Theorizing Through

Literature Reviews: The Miner-Prospector Continuum.

Organizational Research Methods, 26(1), 139-167.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428120943288

CB Insights. (2023). State of Corporate Venture Capital

(CVC) 2023 Report. CB Insights.

Ceccagnoli, M., Higgins, M. J., & Kang, H. D. (2018).

Corporate venture capital as a real option in the markets

for technology. Strategic Management Journal, 39(13),

3355–3381. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2950

Contini, G., & Peruzzini, M. (2022). Sustainability and

Industry 4.0: Definition of a Set of Key Performance

Indicators for Manufacturing Companies. In

Sustainability (Switzerland) (Vol. 14, Issue 17). MDPI.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su141711004

Compaño, R., Napolitano, L., Rentocchini, F., Domnick, C.,

Santoleri, P., Tübke, A., & Mccutcheon, P. (2022).

Summary report of the 6th GLORIA virtual workshop.

https://ec.europa.eu/jrc

Corvello, V., Cimino, A., & Felicetti, A. M. (2023). Building

start-up acceleration capability: A dynamic capability

framework for collaboration with start-ups. Journal of

Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity,

9(3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joitmc.2023.100104

de Klerk, S., Miles, M. P., & Bliemel, M. (2024). A life cycle

perspective of startup accelerators. International

Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 20(1), 327–

343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-023-00933-7

Dhanda, U., & Shrotryia, V. K. (2021). Corporate

sustainability: the new organizational reality. In

Qualitative Research in Organizations and

Management: An International Journal (Vol. 16, Issues

3–4, pp. 464–487). Emerald Group Holdings Ltd.

https://doi.org/10.1108/QROM-01-2020-1886

Di Vaio, A., Hassan, R., Chhabra, M., Arrigo, E., &

Palladino, R. (2022). Sustainable entrepreneurship

impact and entrepreneurial venture life cycle: A

systematic literature review. Journal of Cleaner

Production, 378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.20

22.134469

Dijkstra-Silva, S., Schaltegger, S., & Beske-Janssen, P.

(2022). Understanding positive contributions to

sustainability. A systematic review. In Journal of

Environmental Management (Vol. 320). Academic

Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115802

Corporate Venturing in Sustainability Transition: Conceptual Framework

47

Döll, L. M., Ulloa, M. I. C., Zammar, A., Prado, G. F. do, &

Piekarski, C. M. (2022). Corporate Venture Capital and

Sustainability. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology,

Market, and Complexity, 8(3), 132. https://doi.org/

10.3390/JOITMC8030132

European Commission. (2021). A European green deal:

Striving to be the first climate-neutral continent.

European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/clima/eu-

action/european-green-deal_en

Fairbairn, M., & Reisman, E. (2024). The incumbent

advantage: corporate power in agri-food tech. Journal of

Peasant Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.20

24.2310146

Friese, S. (2019). Qualitative Data Analysis with Atlas.ti (3rd

ed.). SAGE Publications.

Geissdoerfer, M. (2019). Sustainable business model

innovation: Process, challenges and implementation.

https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.39596

George, G., & Schillebeeckx, S. J. D. (2022). Digital

transformation, sustainability, and purpose in the

multinational enterprise. In Journal of World Business

(Vol. 57, Issue 3). Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.10

16/j.jwb.2022.101326

Ghobakhloo, M., Fathi, M., Iranmanesh, M., Maroufkhani,

P., & Morales, M. E. (2021). Industry 4.0 ten years on: A

bibliometric and systematic review of concepts,

sustainability value drivers, and success determinants.

Journal of Cleaner Production, 302, Article 127052.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127052

Gutmann, T. (2019). Harmonizing corporate venturing

modes: an integrative review and research agenda.

Management Review Quarterly, 69(2), 121–157.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-018-0148-4

Gutmann, T., Kanbach, D., & Seltman, S. (2019). Exploring

the benefits of corporate accelerators: Investigating the

SAP Industry 4.0 Startup program. Problems and

Perspectives in Management, 17(3), 218–232.

https://doi.org/10.21511/ppm.17(3).2019.18

Haarmann, L., Machon, F., Rabe, M., Asmar, L., &

Dumitrescu, R. (2023). Venture client model: A

systematic literature review. Proceedings of the 18th

European Conference on Innovation and Entrepre-

neurship, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.34190/ecie.18.1.1790

Hegeman, P. D., & Sørheim, R. (2021). Why do they do it?

Corporate venture capital investments in cleantech

startups. Journal of Cleaner Production, 294.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126315

Hockerts, K., & Wüstenhagen, R. (2010). Greening Goliaths

versus emerging Davids - Theorizing about the role of

incumbents and new entrants in sustainable

entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(5),

481–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.07.005

Hörisch, J. (2018). How business actors can contribute to

sustainability transitions: A case study on the ongoing

animal welfare transition in the German egg industry.

Journal of Cleaner Production, 201, 1155–1165.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.031

Hübel, C., Weissbrod, I., & Schaltegger, S. (2022). Strategic

alliances for corporate sustainability innovation: The

‘how’ and ‘when’ of learning processes. Long Range

Planning, 55(6). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2022.1022

00

Jabareen, Y. (2009). Building a conceptual framework:

Philosophy, definitions, and procedure. International

Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(4), 49–62.

https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690900800406

Jeon, E., & Maula, M. (2022). Progress toward understanding

tensions in corporate venture capital: A systematic

review. Journal of Business Venturing, 37(4).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2022.106226

Jing, L., & Zhang, H. (2023). Venture Capital, Compensation

Incentive, and Corporate Sustainable Development.

Sustainability (Switzerland), 15(7). https://doi.org/10.33

90/su15075899

Karimi Takalo, S., Sayyadi Tooranloo, H., & Shahabaldini

Parizi, Z. (2021). Green innovation: A systematic

literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 279,

122474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122474

Kolte, A., Festa, G., Ciampi, F., Meissner, D., & Rossi, M.

(2023a). Exploring corporate venture capital investments

in clean energy—a focus on the Asia-Pacific region.

Applied Energy, 334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.

2023.120677

Kraus, S., Breier, M., Jones, P., & Hughes, M. (2022).

Literature reviews as independent studies: Guidelines for

academic practice. Review of Managerial Science.

Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/

s11846-022-00588-8

McKinsey Global Institute (2022). The net-zero transition:

What it would cost, what it could bring (Report).

McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/

~/media/mckinsey/business%20functions/sustainability/

our%20insights/the%20net%20zero%20transition%20w

hat%20it%20would%20cost%20what%20it%20could%

20bring/the-net-zero-transition-what-it-would-cost-and-

what-it-could-bring-final.pdf

Lahti, T., Wincent, J., & Parida, V. (2018). A definition and

theoretical review of the circular economy, value

creation, and sustainable business models: Where are we

now and where should research move in the future? In

Sustainability (Switzerland) (Vol. 10, Issue 8). MDPI.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082799

Laibach, N., Kamrath, C., Bröring, S., & Brandt, L. (2023).

Startup selection criteria for corporate venturing: what

matters for incumbents. International Journal of

Entrepreneurial Venturing, 15(4). https://doi.org/10.15

04/ijev.2023.10058682

Leiting, A.-K. (2020). Internal corporate venturing as vehicle

for organizational transformation: Different perspectives

on how incumbent firms adopt entrepreneurial practices

(Doctoral dissertation, ETH Zurich). https://doi.org/

10.3929/ethz-b-000487269

Lin, J. Y. (2020). What affects new venture firm’s innovation

more in corporate venture capital? European

Management Journal, 38(4), 646–660. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.emj.2020.01.004

Livieratos, A. D., & Lepeniotis, P. (2017a). Corporate

venture capital programs of European electric utilities:

Motives, trends, strategies and challenges. Electricity

FEMIB 2025 - 7th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

48

Journal, 30(2), 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tej.201

7.01.006

Loorbach, D., Frantzeskaki, N., & Avelino, F. (2017).

Sustainability transitions research: Transforming science

and practice for societal change. Annual Review of

Environment and Resources, 42(1), 599–626.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102014-

021340

Mac Clay, P., Feeney, R., & Sellare, J. (2024). Technology-

driven transformations in agri-food global value chains:

The role of incumbent firms from a corporate venture

capital perspective. Food Policy, 127. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.foodpol.2024.102684

Magnusson, T., & Werner, V. (2023). Conceptualisations of

incumbent firms in sustainability transitions: Insights

from organisation theory and a systematic literature

review. Business Strategy and the Environment, 32(2),

903–919. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3081

Mäkitie, T. (2020). Corporate entrepreneurship and

sustainability transitions: resource redeployment of oil

and gas industry firms in floating wind power.

Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 32(4),

474–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2019.1668

553

Martins de Souza, A., Puglieri, F. N., & de Francisco, A. C.

(2024). Competitive Advantages of Sustainable Startups:

Systematic Literature Review and Future Research

Directions. Sustainability, 16(17), 7665. https://doi.org/

10.3390/su16177665

Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative content analysis. Forum:

Qualitative Social Research, 1(2). http://dx.doi.org/10.17

169/fqs-1.2.1089

Michelfelder, I., Kant, M., Gonzalez, S., & Jay, J. (2022).

Attracting venture capital to help early-stage, radical

cleantech ventures bridge the valley of death: 27 levers

to influence the investor perceived risk-return ratio.

Journal of Cleaner Production, 376. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.133983

Mrkajic, B., Murtinu, S., & Scalera, V. G. (2019). Is green

the new gold? Venture capital and green

entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 52(4),

929–950. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9943-x

Neumeyer, X., & Santos, S. C. (2018). Sustainable business

models, venture typologies, and entrepreneurial

ecosystems: A social network perspective. Journal of

Cleaner Production, 172, 4565–4579. https://doi.org/

10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2017.08.216

Olteanu, Y., & Fichter, K. (2022). Startups as sustainability

transformers: A new empirically derived taxonomy and

its policy implications. Business Strategy and the

Environment, 31(7), 3083–3099. https://doi.org/10.1002/

bse.3065

Pinkow, F., & Iversen, J. (2020). Strategic objectives of

corporate venture capital as a tool for open innovation.

Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and

Complexity, 6(4), 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc60

40157

PricewaterhouseCoopers. (2022). European Corporate

Venture Capital Value Impact Study. https://www.pwc.

de/en/deals/corporate-venture-capital-value-impact-stud

y.html

Provasnek, A. K., Sentic, A., & Schmid, E. (2017).

Integrating Eco-Innovations and Stakeholder

Engagement for Sustainable Development and a Social

License to Operate. In Corporate Social Responsibility

and Environmental Management (Vol. 24, Issue 3, pp.

173–185). John Wiley and Sons Ltd. https://doi.org/

10.1002/csr.1406

Reihlen, M., Schlapfner, J. F., Seeger, M., & Trittin-Ulbrich,

H. (2022). Strategic Venturing as Legitimacy Creation:

The Case of Sustainability. Journal of Management

Studies, 59(2), 417–459. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.

12745

Reuter, E., & Krauspe, T. (2023). Business Models for

Sustainable Technology: Strategic Re-Framing and

Business Model Schema Change in Internal Corporate

Venturing. Organization and Environment, 36(2), 282–

314. https://doi.org/10.1177/10860266221107645

Röhm, P., Merz, M., & Kuckertz, A. (2020). Identifying

corporate venture capital investors – A data-cleaning

procedure. Finance Research Letters, 32. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.frl.2019.01.004

Salomaa, A., & Juhola, S. (2020). How to assess

sustainability transformations: A review. Global

Sustainability, 3. https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2020.17

Schaltegger, S., Loorbach, D., & Hörisch, J. (2023).

Managing entrepreneurial and corporate contributions to

sustainability transitions. In Business Strategy and the

Environment (Vol. 32, Issue 2, pp. 891–902). John Wiley

and Sons Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3080

Schaltegger, S., Lüdeke-Freund, F., & Hansen, E. G. (2016).

Business Models for Sustainability: A Co-Evolutionary

Analysis of Sustainable Entrepreneurship, Innovation,

and Transformation. Organization and Environment,

29(3), 264–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026616633

272

Sheppard, L., Smith, J., & Brown, A. (2023). Corporate

venture capital as a driver of sustainability in the

consumer goods sector. Journal of Sustainable Business

Practices, 15(2), 123-145. https://doi.org/10.1016/jsbp.

2023.02.001

Schönwälder, J., & Weber, A. (2023). Maturity levels of

sustainable corporate entrepreneurship: The role of

collaboration between a firm’s corporate venture and

corporate sustainability departments. Business Strategy

and the Environment, 32(2), 976–990. https://doi.org/

10.1002/bse.3085

Schuh, G., Budweiser, L., & Lademann, F. (2023). Journal

of Production Systems and Logistics Performance

Management of Corporate Venturing Activities in

Manufacturing Companies: An Exploratory Study.

https://doi.org/10.15488/15764

Shakeel, S. R., & Juszczyk, O. (2019). The Role of Venture

Capital in the Commercialization of Cleantech

Companies. Management, 14(4), 325–339.

https://doi.org/10.26493/1854-4231.14.325-339

Shin, B. Y., & Cho, K. T. (2020). The evolutionary model of

corporate entrepreneurship: A case study of samsung

Corporate Venturing in Sustainability Transition: Conceptual Framework

49

creative-lab. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(21), 1–23.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219042

Shu, C., Liu, J., Zhao, M., & Davidsson, P. (2020). Proactive

environmental strategy and firm performance: The

moderating role of corporate venturing. International

Small Business Journal, 38(7), 654-676.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242620923897

Silicon Valley Bank. (2023). State of CVC. Silicon Valley

Bank. https://www.svb.com/trends-insights/reports/state

-of-cvc/

Soratto, J., de Pires, D. E. P., & Friese, S. (2020). Thematic

content analysis using ATLAS.ti software: Potentialities

for researchs in health. Revista Brasileira de

Enfermagem, 73(3). https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-

2019-0250

Stöhr, J., & Herzig, C. (2022). Organic pioneers and the

sustainability transformation of the German food market:

a politically structuring actor perspective. British Food

Journal, 124(7), 2321–2342. https://doi.org/10.1108/

BFJ-08-2021-0953

Surana, K., Edwards, M. R., Kennedy, K. M., Borrero, M. A.,

Clarke, L., Fedorchak, R., Hultman, N. E., McJeon, H.,

Thomas, Z., & Williams, E. D. (2023). The role of

corporate investment in start-ups for climate-tech

innovation. In Joule (Version 1). Zenodo. https://doi.org/

10.5281/zenodo.7643737

Sustainable Development Solutions Network. (2024). The

sustainable development report 2024. https://www.

unsdsn.org/resources/the-sustainable-development-repor

t-2024/

Tandon, A., Chaudhary, S., Nijjer, S., Vilamová, Š., Tekelas,

F., & Kaur, P. (2024). Challenges in sustainability

transitions in B2B firms and the role of corporate

entrepreneurship in responding to crises created by the

pandemic. Industrial Marketing Management, 118, 93–

109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2024.01.019

Tang, M., Liu, Y., Hu, F., & Wu, B. (2022). Effect of digital

economy development on enterprises’ green innovation:

Empirical evidence from listed companies in China.

SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4302335

United Nations Global Compact. (2023). European private

sector SDG stocktake. United Nations Global Compact.

https://info.unglobalcompact.org/sdg-stocktake

Urbano, D., Turro, A., Wright, M., & Zahra, S. (2022).

Corporate entrepreneurship: a systematic literature

review and future research agenda. Small Business

Economics, 59(4), 1541–1565. https://doi.org/10.1007/

s11187-021-00590-6

Van der Waldt, G., 2020, ‘Constructing conceptual

frameworks in social science research’, The Journal for

Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa 16(1),

a758. https://doi.org/10.4102/td.v16i1.758

Westman, L., Luederitz, C., Kundurpi, A., Mercado, A., &

Burch, S. (2022). Market transformations as

collaborative change: Institutional coevolution through

small business entrepreneurship. Business Strategy and

the Environment, 32(2), 936–957.

Woolley, J. L., & MacGregor, N. (2022). The Influence of

Incubator and Accelerator Participation on

Nanotechnology Venture Success. Entrepreneurship

Theory and Practice, 46(6), 1717-1755. https://doi.org/

10.1177/10422587211024510

World Intellectual Property Organization. (2020). What is a

patent? Retrieved from https://www.wipo.int/patents/en/

Wunder, D., & Maula, M. (2024). Harvesting or nurturing?

Corporate venture capital and startup green innovation.

Academy of Management Proceedings, 2024(1).

https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2024.1790

Yasir, N., Babar, M., Mehmood, H. S., Xie, R., & Guo, G.

(2023). The Environmental Values Play a Role in the

Development of Green Entrepreneurship to Achieve

Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intention. Sustainability

(Switzerland), 15(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086

451

Ystrom, A., Agogue, M., & Rampa, R. (2021). Preparing an

Organization for Sustainability Transitions-The Making

of Boundary Spanners through Design Training.

SUSTAINABILITY, 13(14). https://doi.org/10.3390/su

13148073

Zucchella, A., Sanguineti, F., & Contino, F. (2023).

Collaborations between MNEs and entrepreneurial

ventures. A study on Open Innovability in the energy

sector. International Business Review. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.ibusrev.2023.102228

FEMIB 2025 - 7th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

50