Analysis of the Continuous Effects of Assertive Feedback from a Job

Interview Training Agent

Tomoko Koda

1,2 a

, Kota Yamauchi

2

, Nao Takeuchi

1b

and Miho Hotta

3c

1

Graduate School of Information Science and Technology, Osaka Institute of Technology, 1-79-1,

Kitayama, Hirakata-city, Osaka, Japan

2

Department of Information Science and Technology, Osaka Institute of Technology,

1-79-1, Kitayama, Hirakata-city, Osaka, Japan

3

Faculty of Applied Sociology, Kindai University, 3-4-1 Kowakae, Higashiosaka City, Osaka, Japan

Keywords: Assertive Communication, Job Interview, Virtual Agent, Nonverbal Behaviour, Multimodal Interaction, Gaze,

Posture, Facial Expression, Social Signal Processing, HAI, IVA.

Abstract: In this study, we developed an interview training agent system that identifies areas for improvement in

interviewees’ nonverbal behaviours (eye gaze, facial expression, and posture) and verified its effectiveness in

providing feedback using assertive communication in a series of experiments. Assertive communication is a

method of conveying one’s opinions and sentiments while respecting another person's position and opinions.

The effectiveness of the feedback was verified in two conditions: the assertive feedback condition, in which

the agent provided feedback while expressing its sentiments, in addition to identifying areas for improvement

and offering suggestions for improvement; and the control condition, in which the agent solely identified areas

for improvement. The preliminal results showed that assertive feedback was effective in improving the

acceptability and usefulness of the feedback and agents' interpersonal impressions. In addition, as a continuous

effect of the three interview practices, the agent's interpersonal impression improved as the number of times

the participants received assertive feedback increased.

1 INTRODUCTION

Interview training is useful for acquiring skills

through exposure to the content and flow of job

interviews, and can increase interviewees’

confidence. In recent years, social signal processing

techniques employing multimodal information have

been used for dialog analysis (

Vinciarelli,2009;

Burgoon, 2017; Okada, 2016) and have been applied

to AI-based interview systems (MIDAS

1

;

ZENKIGEN

2

; Naim, 2015; Rao, 2017) and interview

training systems (Goda, 2017; Barur, 2013; Smith,

2015; Tanaka, 2015). Some systems visualise the

nonverbal behaviour of the interviewee and provide

feedback on the interview (Anderson, 2013; Damian,

2015; Hoque, 2013; Langer, 2016), whereas others

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9999-1240

b

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-3964-7061

c

https://orcid.org/0009-0005-0688-4315

provide feedback through a virtual agent (Barur,

2013; Callejas, 2014; Gebhard, 2014).

Several studies have shown that practising

interviews with a virtual agent as an interviewer is

more effective in improving interviewee performance

than with human interviewers (Damian, 2015; Lucas,

2014; Lucas, 2017) and reduces interview anxiety

(Langer, 2016). However, these studies focused on

the effects of using virtual agents, and not on the

communication methods agents use during the

interviews. Our previous study showed that a virtual

agent providing rational feedback with numerical

evidence is rated as more reliable but less friendly

than non-rationalised feedback (Takeuchi, 2021).

In this study, we focused on assertive

communication and implemented it as a

communication method for virtual agents. Assertive

1

MIDAS Information Technology Co., Ltd., https://

www.inair.co.jp/ (6, January, 2025)

2

ZENKIGEN Co., Ltd., https://harutaka.jp/ (6, January,

2025)

Koda, T., Yamauchi, K., Takeuchi, N. and Hotta, M.

Analysis of the Continuous Effects of Assertive Feedback from a Job Interview Training Agent.

DOI: 10.5220/0013244000003890

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART 2025) - Volume 1, pages 531-536

ISBN: 978-989-758-737-5; ISSN: 2184-433X

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

531

communication is a method of expressing one's

opinions and sentiments in a way that the self-esteem

and the feelings of others are not affected, and has

been used in corporate training (Hotta, 2013; Niiya,

2015; Ilie, 2015). Therefore, we believe that assertive

communication is suitable for interview training, in

which negative opinions must be conveyed, as it

allows advisors to make their points respectfully.

In a series of experiments, we examined the

continuous effectiveness of feedback incorporating

assertive communication from a virtual agent in terms

of the acceptability and usefulness of the feedback

and interpersonal impressions of the feedback agent.

2 JOB INTERVIEW TRAINING

SYSTEM

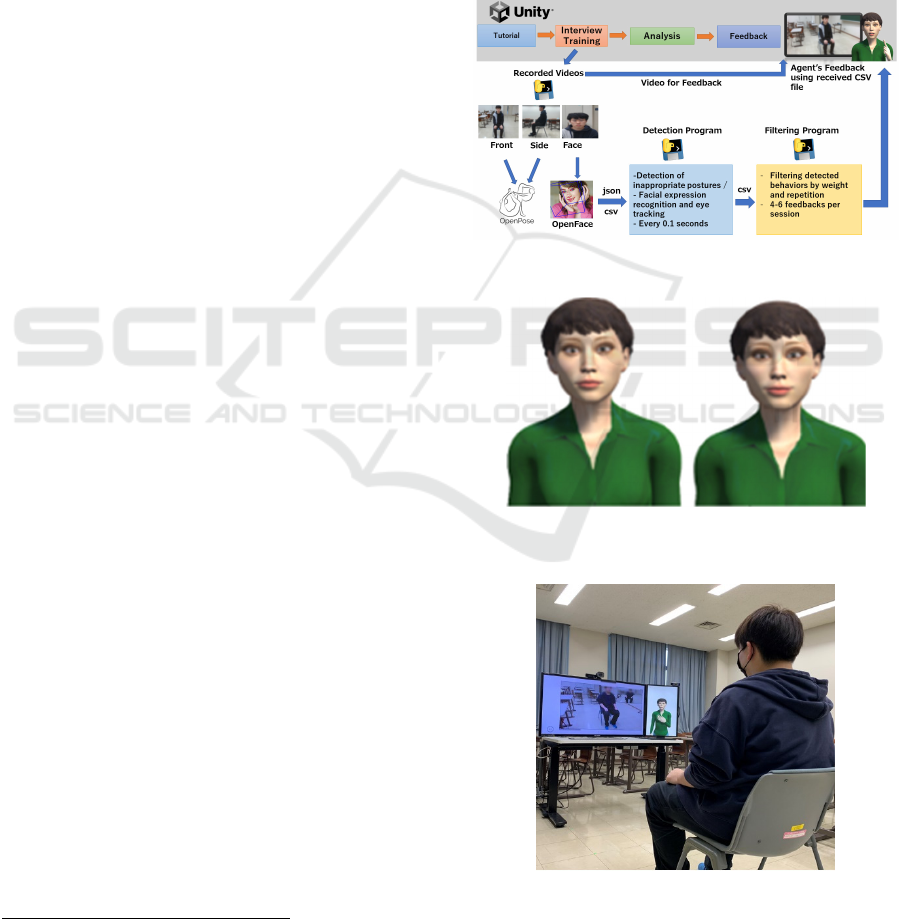

Our job interview training system (Takeuchi, 2021a;

Takeuchi, 2021b; Takeuchi, 2021c; Koda, 2023) has

been developed using Unity, Python, OpenFace

3

and

OpenPose

4

. The training procedure consisted of

interview, analysis, and feedback phases, as shown in

Figure 1. In the interview phase, participants

underwent a mock interview by providing a one-

minute self-presentation while sitting in front of a 40-

inch display. Three webcams were used to capture the

front, side, and face of the participants’ bodies.

During the analysis phase, the videos were analysed

using OpenPose and OpenFace, and the analysed data

were used to detect inappropriate nonverbal

behaviours. Inappropriate nonverbal behaviours were

detected by comparing the interviewees’ postures and

facial expressions with those of a professional

interview counsellor. In the feedback phase, the CG

agent (Figure 2) appeared on the display and provided

feedback on selected inappropriate behaviours while

playing and pausing the video. Figure 3 shows an

actual image of a participant taking part in the

experiment and being given a feedback from the CG

agent while watching his video playback.

Detectable nonverbal behaviours include postures

(i.e., hunched, leaning back, upright), feet positions

(i.e., forward, backward, dangling, vertical), neck

(i.e., upward, downward, straight), crossed legs, leg

spread (i.e., wider than shoulder width, gradually

opening), elbow extension, hands (position,

movement), facial expressions (i.e., tight lip corners),

and gaze orientations (upward, downward, left/right).

The assertive feedback used in this study was

based on the elements of assertive communication

3

OpenFace, https://github.com/TadasBaltrusaitis/

OpenFace (6, January, 2025)

(Hotta, 2013) and has the following structure: First,

“facts/problems (issues to be corrected)” are

communicated, then “sentiments” of the CG agent

toward the facts/problems are expressed, and finally

“suggestions” on how to improve the issues are given.

A concrete example is: “At this moment, you were

hunched over (fact/problem). I think it is a pity

because it makes you look unconfident, no matter

how good your speech is (sentiment). Therefore, you

should try to straighten your back with your chin

pulled back and put some strength in your lower

abdomen. Good posture improves your impression,

Figure 1: Interview and feedback procedure.

Figure 2: Examples of facial expressions of the CG agent

(left: neutral, right: smile).

Figure 3: Experiment scene.

4

OpenPose, https://github.com/CMU-Perceptual-

Computing-Lab/openpose (6, January, 2025)

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

532

and makes you look confident and persuasive

(suggestion).” In addition, we implemented eye and

face directions, facial expressions, and gestures as

nonverbal behaviours during agent feedback, as

shown in Figure 2.

3 EVALUATION EXPERIMENT

The purpose of the experiment was to verify the

effectiveness of assertive feedback in terms of “the

usefulness of feedback (acceptability and

usefulness)” and “the interpersonal impression of the

feedback agent (perceived friendliness and

aggressiveness)”. We compared the effectiveness of

two conditions: the assertive feedback condition (AF

condition), in which the CG agent gave feedback on

facts/problems and suggestions while expressing

their sentiments, and the control condition (CF

condition), in which the agent gave feedback on

facts/problems only.

The evaluation experiments were conducted

using a within-subject design, in which each

participant was interviewed three times for each

condition. The participants were given two mock

interviews and feedbacks on both conditions (order is

randomly assigned) per day. The experiment was

conducted three times on separate days. Twenty-three

university students (male: 23, female: 3; age range:

21–24 years old) participated in the experiment and

completed a questionnaire after each experiment. The

questions were on the acceptability of the feedback

(i.e., “I felt I could accept the agent's feedback.”),

usefulness of the feedback (i.e., “I would like to

continue practising interviews with the agent in this

system.”), perceived friendliness of the agent (i.e., “I

had a favourable impression of the agent.”), and

perceived aggressiveness of the agent (i.e., “I

perceived criticism from the agent.”).

The following four hypotheses were formulated

for this experiment:

H1: Assertive feedback improves feedback

usefulness (higher acceptability and usefulness

compared to the CF condition).

H2: Assertive feedback improves a feedback

agent's interpersonal impression (higher friendliness

and lower aggressiveness compared to the CF

condition).

H3: Continuous assertive feedback does not

decrease its usefulness (maintains a certain level of

acceptability and usefulness).

H4: Continuous assertive feedback improves the

feedback agent's interpersonal impressions (increased

friendliness and decreased aggressiveness).

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A one-factor analysis of variance was conducted for

the questionnaire answers with two levels of agent

factors (AF and CF conditions, repeated measures). A

two-factor analysis of variance was conducted on the

two levels of the agent factor and three levels of the

number of experimental factors (#1, #2, and #3).

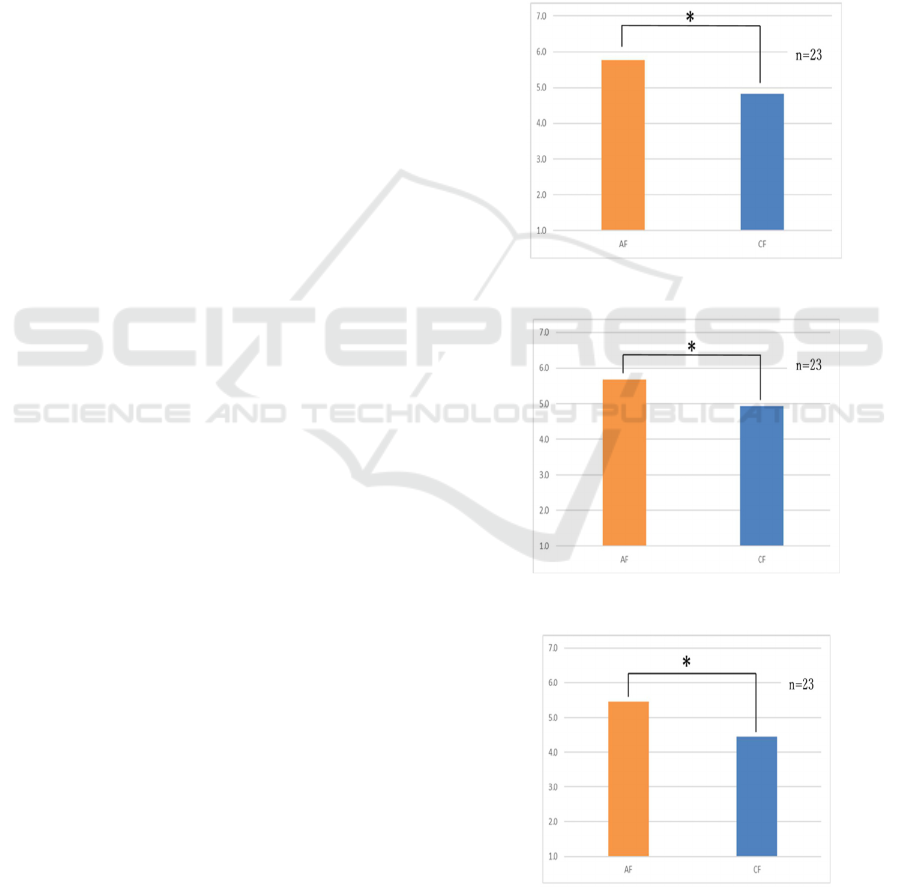

The usefulness of the feedback was evaluated by

comparing the acceptability and usefulness of each

condition. In the acceptability evaluation, the AF

condition was found to be significantly higher than

the CF condition (Figure 4, AF=5.8, CF=4.9,

F=43.177, p=0.000). The AF condition was evaluated

as significantly higher than the CF condition for

usefulness (Figure 5, AF=5.7, CF=4.9, F=43.240,

p=0.000). Thus, H1 is supported. This result suggests

that assertive feedback improves the usefulness of

feedback because feedback in the AF condition was

more specific than in the CF condition, conveying

specific points for improvement along with

sentiments.

In both the AF and CF conditions, there were no

significant differences in the acceptability ratings

based on the number of experimental factors.

Therefore, H3 is supported; although the usefulness

ratings in the AF condition were higher than those in

the CF condition, we believe that receiving feedback

had a continuous effect on usefulness ratings in both

conditions.

Next, we compared the interpersonal impression

ratings of the friendliness and aggressiveness of the

agent between the two conditions. The results showed

that the AF condition was rated significantly higher

than the CF condition in terms of friendliness (Figure

6, AF=5.5, CF=4.5, F=122.550, p=0.000). The CF

condition was rated significantly higher for

aggressiveness than the AF condition (Figure 7,

AF=1.5, CF=1.8, F=17.436, p=0.000). Thus, H2 is

supported. The reason the AF condition was rated

significantly higher than the CF condition on

friendliness and the AF condition was rated

significantly lower than the CF condition on

aggressiveness was thought to be due to the presence

of sentiments. These results suggest that assertive

feedback effectively improves the agents'

interpersonal impressions of friendliness and

aggressiveness.

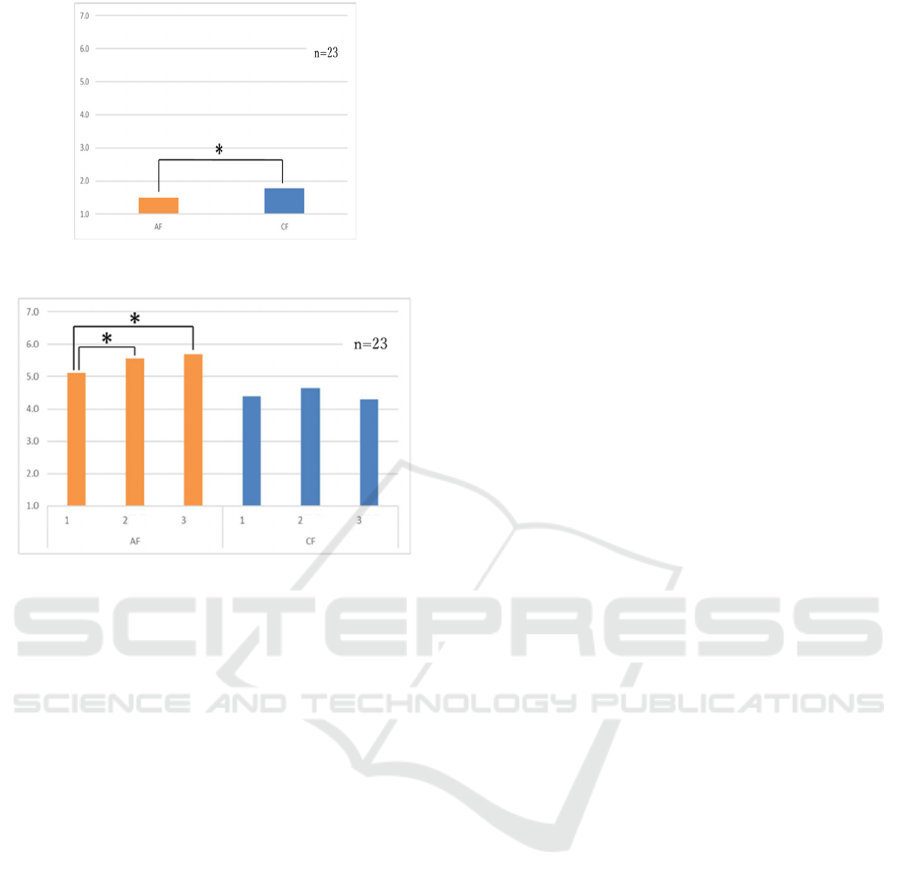

Regarding friendliness, the second and third

experiments were rated significantly higher than the

first in terms of the number of experimental factors

(#1=4.8, #2=5.1, #3=5.0, F=9.205, p=0.000,

p=0.004). Furthermore, an interaction between the

agent factor and the number of experimental factors

Analysis of the Continuous Effects of Assertive Feedback from a Job Interview Training Agent

533

was observed, indicating that the agent’s friendliness

in the second and third experiments was rated

significantly higher than that in the first experiment

in the AF condition. However, the friendliness ratings

in the CF condition did not change during the three

experiments (Figure 8, F=7.907, p=0.000, p=0.000).

Aggressiveness ratings did not differ significantly

with the number of experiments. Thus, H4 is partially

supported in terms of friendliness. This indicates that

the continued effect of assertive feedback is likely to

manifest as an improvement in an agent’s

friendliness.

Although the preliminal results suggest positive

effects on the assertive feedback, this study is limited

in that it compared the condition in which the agent

solely identified areas for improvement with the

assertive condition. It is necessary to dissect the

elements of assertive communication

(facts/problems, suggestions, sentiments) to identify

their individual contributions on the evaluation of

usefulness and interpersonal impressions.

Specifically, four conditions should be prepared: one

in which only facts/problems are fed back, one in

which facts/problems and suggestions are fed back,

one in which facts/problems and sentiments are fed

back, and one in which facts/problems, suggestions,

and sentiments are fed back.

In addition to the subjective evaluations

conducted in this study, an objective evaluation of

assertive feedback by comparing the number of

detected nonverbal behaviours for improvement over

time is necessary. Furthermore, based on the

comments from the participants in the experiment

(i.e., "It's okay to start with the AF condition, but I’d

prefer to move on to the CF condition as I practice

interviews" and "I want to use the CF condition

during the period of repeated practice and the AF

condition when there is a sense of urgency, such as

right before a real job interview"), we need to develop

a job interview training agent that changes the

feedback method according to the context of job

search activities.

In terms of applying our interview training system

for practical use, we shoud modify the critaria for

detecting the inappropriate behaviors. The detection

of the inappropriate posture, eye gaze, and facial

expressions in our interview practice system was

based on the criteria for judgment during interviews

with newly graduated students in Japan. In Japan,

there are strict standards for non-verbal behaviours

during interviews, particularly with regard to posture:

the upper body should be upright and the hands

should be on the knees. However, in other countries,

a more relaxed posture is considered acceptable.

Therefore, if this system is to be applied outside of

Japan, the criteria should be modified to match the

standards of that country.

It is also necessary to compare usefulness and

interpersonal impressions when the same assertive

feedback is given by a human interviewer and a CG

agent, as the impression between the human and the

agent giving the feedback may change. We would like

to further verify the effectiveness of the feedback by

changing the gender and appearance of the agent and

by comparing the effectiveness of assertive feedback

across cultures.

Figure 4: Acceptability of the feedback.

Figure 5: Usefulness of the feedback.

Figure 6: Friendliness of the agent.

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

534

Figure 7: Aggressiveness of the agent.

Figure 8: Friendliness of the agent compared by the number

of experiments.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we evaluated the continuous effects of

assertive feedback in terms of its usefulness and the

interpersonal impression of the feedback agent in a

series of interview training experiments. The results

showed that assertive feedback was evaluated higher

in terms of usefulness and interpersonal impression

than the condition in which the agent simply

suggested points to be improved, and that the

evaluation did not decrease over time; that is, the

effect of assertive feedback was sustained. The results

also suggest that assertive feedback continuously

improves the agents’ perceived friendliness.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A part of this work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for

Scientific Research "KAKENHI (C) 20K11926".

REFERENCES

Anderson, K., Andre, E., Baur, T., Bernardini, S., Chollet, M.,

Chryssafidou, E., Damian, I., Ennis, C., Egges, A.,

Gebhard, P., Jones, H., Ochs, M., Pelachaud, C., Porayska-

Pomsta, K., Rizzo, P., and Sabouret, N. (2013). The

TARDIS framework: Intelligent virtual agents for social

coaching in job interviews. In ACE’13, 476–491.

Barur, T., Damian, I., Gebhard, P., Porayska-Pomsta, K., and

Andre, E. (2013). A Job Interview Simulation: Social Cue-

Based Interaction with A Virtual Character. In IEEE

International Conference on Social Computing

(SocialCom2013), 220–227.

Burgoon, J. K., Magnenat-Thalmann, N., Pantic, M. and

Vinciarelli, A. (2017). Social Signal Processing,

Cambridge University Press.

Callejas, Z., Ravenet, B., Ochs, M., and Pelachaud, C. (2014).

A computational model of social attitudes for a virtual

recruiter. In AAMAS’14, 93–100.

Damian, I., Baur, T., Lugrin, B., Gebhard, P., Mehlmann, G.,

and Andre, E. (2015). Games are better than books: In-situ

comparison of an interactive job interview game with

conventional training. In AIED’15, 84–94.

Gebhard, P., Baur, T., Damian, I., Mehlmann, G., Wagner, J.,

and Andre, E. (2014). Exploring interaction strategies for

virtual ´ characters to induce stress in simulated job

interviews. In AAMAS’14, 661–668.

Goda, N., Ishihara, K., and Kojiri, T. (2017). Job Interview

Support System Based on Analysis of Nonverbal

Behavior. In IEICE Technical Report, 116(517), ET2016-

98, 25-30.

Hoque, M. E., Courgeon, M., Martin, J.-C., Mutlu, B., and

Picard, R. W. (2013). MACH: My automated conversation

coach. In UBICOMP’13, 697–706.

Hotta, M. (2013). Issues in assertiveness training effectiveness

research. Journal of Educational Psychology, 61, 412-424.

Ilie, O. and Metea, I. (2015). Empathic And Assertive

Communication. Efficient Communication

Developments. In Procs. of International conference

Knowledge-based Organization, 21 (1), 214-217.

Koda, T., Takeuchi, N., and Hotta, M. (2023). Analysis of the

Effects of Assertive Feedback from a Job Interview

Training Agent. In Procs. of 11th International Conference

on Human-Agent Interaction (HAI’23), 384-386. DOI:

10.1145/3623809.3623933.

Langer, M., Konig, C. J., Gebhard, and P., Andre, E. (2016).

Dear computer, teach me manners: Testing virtual

employment interview training. In International Journal of

Selection and Assessment, 24 (4), 312–323.

Lucas, G.M., Gratch, J., King, A., and Morency, L.P. (2014).

It’s only a computer: Virtual humans increase willingness

to disclose. In Computers in Human Behavior, 37, 94-100.

Lucas, G.M., Rizzo, A., Gratch, J., Scherer, S., Stratou, G.,

Boberg, J., and Morency, L.P. (2017). Reporting Mental

Health Symptoms: Breaking Down Barriers to Care with

Virtual Human Interviewers. In Frontiers in Robotics and

AI, 4, 51.

Naim, I., Tanveer, M. I., Gildea, D., and Hoque, M. E. (2015).

Automated prediction and analysis of job interview

Analysis of the Continuous Effects of Assertive Feedback from a Job Interview Training Agent

535

performance: The role of what you say and how you say it,

In IEEE FG’15.

Niiya, Y., and Crocker, J. (2015). Acquiring Knowledge and

Learning from Failure: Theory, Measurement, and

Validation of Two Learning Goals. In GIS journal: the

Hosei journal of global and interdisciplinary studies, 1, 67-

112.

Okada, S., Matsugi, Y., Nakano, Y., Hayashi, Y., Huang, H.,

Takase, Y., and Nitta, K. (2016). Estimating

Communication Skills based on Multimodal Information

in Group Discussions. In Journal of the Japanese Society

for Artificial Intelligence, Vol.31, No.6, A130-E.

Rao S. B, P., Rasipuram, S. and Das, R., Jayagopi, D. B.

(2017). Automatic assessment of communication skill

innon-conventional interview settings: A comparative

study, In ICMI’17, 221–229.

Smith, M., Humm, L. et al. (2015). Virtual Reality Job

Interview Training for Veterans with Posttraumatic Stress

Disorder. In Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 42, 271–

279.

Tanaka, H., Sakti, S., Neubig, G., Toda, T., Negoro H.,

Iwasawa H., and Nakamura. S. (2015). Automated Social

Skills Trainer. In Procs. of the 20th International

Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces (IUI’15), 17–27.

Takeuchi, N., and Koda, T. (2021a). Impression of a Job

Interview training agent that gives rationalized feedback: -

Should Virtual Agent Give Advice with Rationale? -. In

Procs. of ACM Multimedia Asia (MMASIA’21), 1-5.

DOI: 10.1145/3469877.3493598

Takeuchi, N., and Koda, T. (2021b). Job Interview Training

System using Multimodal Behavior Analysis. In Procs. of

9th International Conference on Affective Computing &

Intelligent Interaction (ACIIW), 1-3. DOI:

10.1109/ACIIW52867.2021.9666270.

Takeuchi, N., and Koda, T. (2021c). Initial Assessment of Job

Interview Training System using Multimodal Behavior

Analysis. In Procs. of 9th International Conference on

Human-Agent Interaction (HAI2021), 407-411. DOI:

10.1145/3472307.3484688

Vinciarelli, A., Pantic, M. and Bourlard, H. (2009). Social

signal processing: Survey of an emerging domain. In

Image and Vision Computing, 27, 12, 1743-1759.

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

536