Segmentation of Intraoperative Glioblastoma Hyperspectral Images

Using Self-Supervised U-Net++

Marco Gazzoni

1 a

, Marco La Salvia

1 b

, Emanuele Torti

1 c

, Elisa Marenzi

1 d

, Raquel Leon

2 e

,

Samuel Ortega

3 f

, Beatriz Martinez

2 g

, Himar Fabelo

2,4 h

, Gustavo Callicò

2 i

and

Francesco Leporati

1 j

1

University of Pavia, Department of Electrical, Computer and Biomedical Engineering, Via Ferrata 5, Pavia I-27100, Italy

2

Research Institute for Applied Microelectronics, University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (ULPGC), 35017 Las Palmas

de Gran Canaria, Spain

3

Norwegian Institute of Food, Fisheries and Aquaculture Research, 9019 Tromsø, Norway

4

Fundación Canaria Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Canarias and the Research Unit, Hospital Universitario de

Gran Canaria Dr. Negrin, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain

Keywords: Brain Cancer, Computer-Aided Diagnosis, Deep Learning, Disease Diagnosis, Hyperspectral Imaging,

Self-Supervised Learning.

Abstract: Brain tumour resection yields many challenges for neurosurgeons and even though histopathological analysis

can help to complete tumour elimination, it is not feasible due to the extent of time and tissue demand for

margin inspection. This paper presents a novel attention-based self-supervised methodology to improve

current research on medical hyperspectral imaging as a tool for computer-aided diagnosis. We designed a

novel architecture comprising the U-Net++ and the attention mechanism on the spectral domain, trained in a

self-supervised framework to exploit contrastive learning capabilities and overcome dataset size problems

arising in medical scenarios. We operated fifteen hyperspectral images from the publicly available HELICoiD

dataset. Enhanced by extensive data augmentation, transfer-learning and self-supervision, we measured

accuracy, specificity and recall values above 90% in the automatic end-to-end segmentation of intraoperative

glioblastoma hyperspectral images. We evaluated our outcomes with the ground truths produced by the

HELICoiD project, obtaining results that are comparable concerning the gold-standard procedure.

1 INTRODUCTION

Brain and Central Nervous System (CNS) cancers are

ranked in the 12th position in terms of mortality,

concerning both genders, with 248,500 deaths

worldwide in 2022, according to the International

Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) of the World

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4213-8270

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3724-8213

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8437-8227

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4537-5618

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4287-3200

f

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7519-954X

g

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7835-9660

h

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9794-490X

i

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3784-5504

j

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2901-4935

Health Organization (WHO) (Bray et al., 2024).

Particularly, brain tumours represent the most

common CNS cancer type (Bray et al., 2024). The

WHO classifies such tumours into four grades (Louis

et al., 2021) and glioblastoma (GB - Grade 4) is the

deadliest one, with an age-standardized 5-year

Gazzoni, M., La Salvia, M., Torti, E., Marenzi, E., Leon, R., Ortega, S., Martinez, B., Fabelo, H., Callicò, G. and Leporati, F.

Segmentation of Intraoperative Glioblastoma Hyperspectral Images Using Self-Supervised U-Net++.

DOI: 10.5220/0013245900003912

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 20th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications (VISIGRAPP 2025) - Volume 3: VISAPP, pages

633-639

ISBN: 978-989-758-728-3; ISSN: 2184-4321

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

633

survival rate in the 2010-2014 period of 4% to 17%

(Girardi et al., 2023).

Currently, the standard treatment for GB tumours

is surgery, followed by radiotherapy or

chemotherapy. To achieve maximal tumour

resection, neurosurgeons use several intraoperative

tools (Fabelo et al., 2016, 2018; Florimbi et al., 2020)

which, nevertheless, exhibit several constraints,

mainly cost and time, and also do not precisely

outline tumour borders (Halicek et al., 2019).

Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI) is a non-invasive,

non-ionizing and label-free technique (Torti et al.,

2023), that is becoming more popular in the context

of cancer detection thanks to recent technological

advances (Kumar et al., 2021; Lu et al., 2014).

Moreover, several studies highlighted that tumour

cells present a unique molecular spectral signature

and reflectance characteristics (Florimbi et al., 2020;

Leon et al., 2021).

During the last decade, Machine and Deep

Learning (ML, DL) solutions emerged as innovative

tools to examine and cluster different cancer types

using HSI (Collins et al., 2021; Jansen-Winkeln et al.,

2021; La Salvia et al., 2023; Salvia et al., 2022).

Concerning intraoperative GB segmentation of HS

images, this research mainly emerged within the

European project HELICoiD (HypErspectraL

Imaging Cancer Detection) (Fabelo et al., 2016).

Here, an in vivo human brain HS database was

created and several ML and basic DL pipelines were

developed (Florimbi et al., 2020). In this field, the

main challenge is retrieving a target ground truth to

supervise ML algorithms, as physicians can only

partially identify the tumour and its boundaries when

performing a diagnosis (Fabelo et al., 2019).

Therefore, HELICoiD-based ML studies comprised

supervised and unsupervised algorithms to overcome

this problem and perform automatic segmentation of

intraoperative-captured HS images.

Lately, self-supervised learning (SSL) is emerging

as a framework to operate small-sized datasets with

limited labelling (Wang et al., 2022; Yue et al., 2022;

Zhu et al., 2022). SSL algorithms work by distilling

representative characteristics from unlabelled and

unstructured data, learning shared and separate

features in a contrastive manner, surpassing supervised

architectures on many domains (Wang et al., 2022).

To the best of the authors' knowledge, no prior

work exists concerning medical brain tumour HS

images and SSL. Hence, here we propose a novel self-

supervised deep learning architecture, an attention-

based U-Net++, as a proof-of-concept to perform the

automatic end-to-end segmentation of fifteen

intraoperative GB HS images retained from the

HELICoiD database (Fabelo et al., 2019).

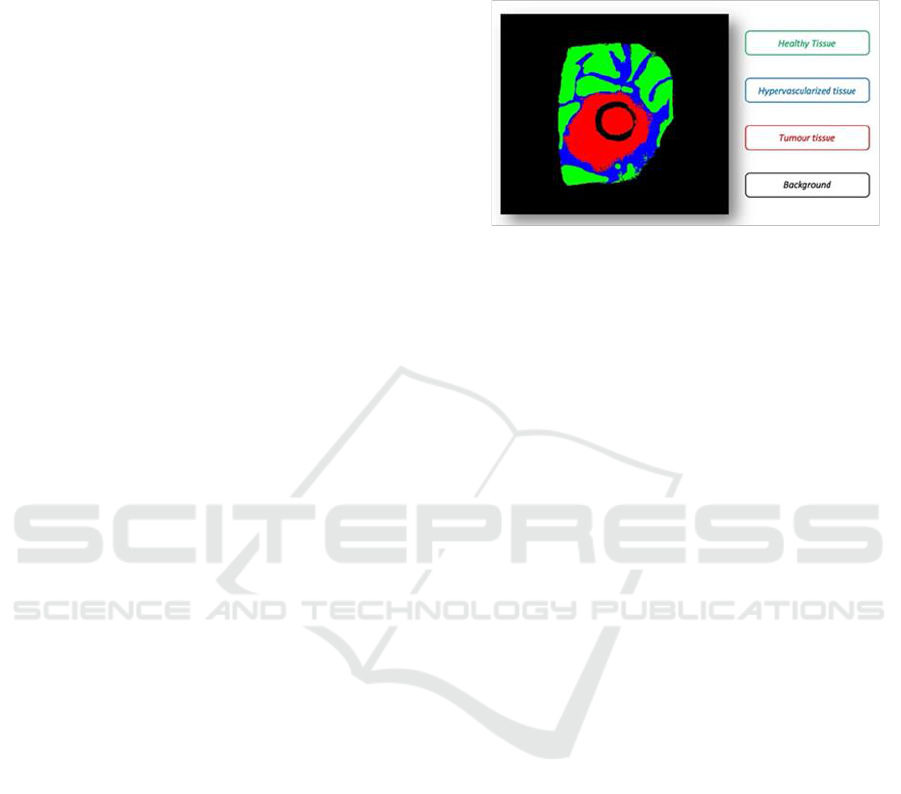

Figure 1: Taxonomy of intraoperative GB segmentation

ground truth derived by manually correcting HELICoiD

results to smoothen the borders.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 In-Vivo HS Human Brain Dataset

and Pre-Processing

We operated 27 GB HS images derived from the

HELICoiD database (Fabelo et al., 2016; Florimbi et

al., 2020). Data was captured using an intraoperative

HS acquisition system at The University Hospital

Doctor Negrin of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (Spain)

(Fabelo et al., 2018). The Comité Ético de

Investigación Clínica-Comité de Ética en la

Investigación (CEIC/CEI) of the University Hospital

Doctor Negrin approved the study and the informed

consent was signed by all participating patients.

Physicians labeled each spatial pixel according to

the taxonomy proposed in Fig. 1, employing a semi-

automatic labelling tool based on the Spectral Angle

Mapper (SAM) method (Fabelo et al., 2019). In this

way, a ground-truth map was generated for each HS

image, where the neurosurgeon selected reference

pixels from normal, tumor, hypervascularized and

background classes. Therefore, the SAM algorithm

clustered pixels that resulted similar to the reference

spectral signatures. The tumor tissue class was

assessed by histopathology.

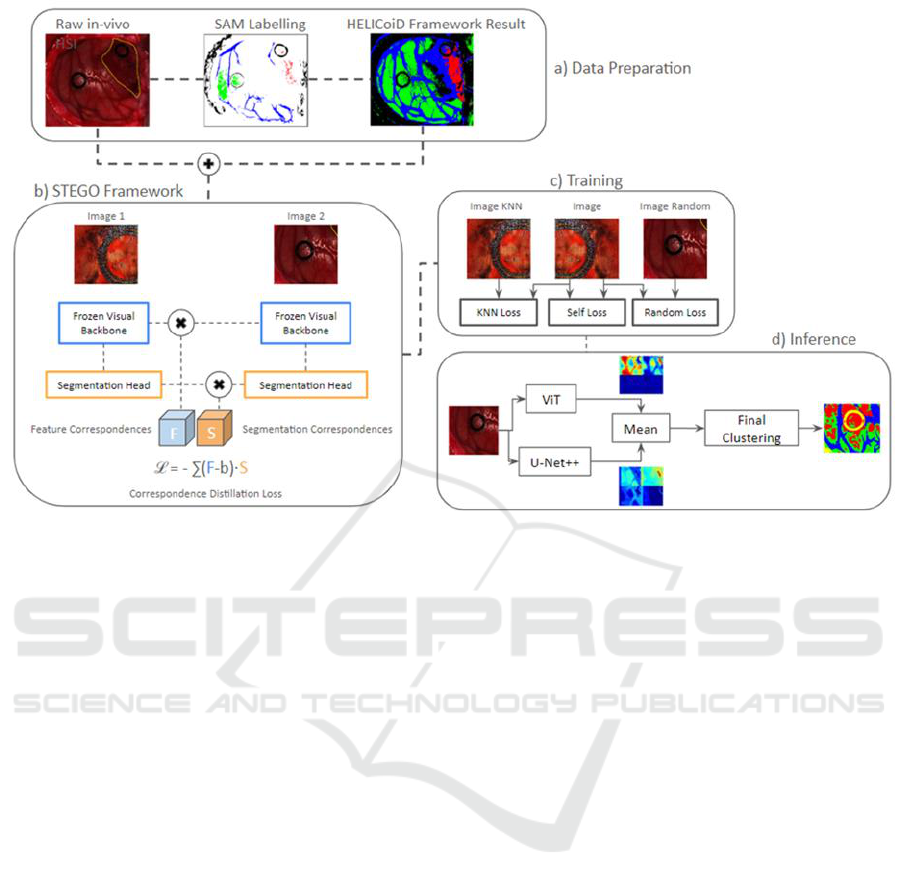

The HELICoiD ML framework starts by pre-

processing the raw HS images captured by the

intraoperative HS acquisition system and ends by

generating a four-color thematic map after

performing supervised and unsupervised

classification (Fig. 2).

The pre-processing chain applied to the HS image

is detailed in (Florimbi et al., 2020), reducing the

VISAPP 2025 - 20th International Conference on Computer Vision Theory and Applications

634

Figure 2: Data preparation, STEGO framework, training and inference resulting from SSL: the raw in-vivo HS images are

pre-processed (Florimbi et al., 2020) and cropped for homogeneity reasons. In addition, in section a), the SAM labelling is

performed only once during the Helicoid framework training to derive the resulting images shown on the right. These, the

pre-processed and the cropped images represent the input to the STEGO framework, in b), employed for segmentation

purposes using supervised learning with U-Net++ backbone network. c) presents the three unsupervised loss functions

adopted in the training phase and how they are combined, while d) details the inference process, using SSL through the

definition of a hybrid network obtained combining the outputs of the parallel execution of U-Net++ and ViT.

instrumentation noise and limiting the curse of data

dimensionality. After preprocessing, HS images

featured 128 spectral bands and cropped to equal

spatial dimensions. The raw HS images were

calibrated for dark noise correction, using a dark and

a white reference (Fabelo et al., 2016; Florimbi et al.,

2020). Moreover, the extreme noisy bands were

removed due to the low performance of the sensor,

obtaining an HS cube of 645 spectral bands. After

that, to avoid redundant information, the HS cube was

decimated to 128 spectral bands and normalized

between 0 and 1.

2.2 Data Partitioning

The dataset employed is composed of 27 images

partitioned at patient-level and divided in 3 subsets:

15 images together with their ground-truths are used

for the supervised training, 11 (without ground-

truths) for the unsupervised training and 1 for test.

Each image has been resized to obtain a spatial

dimension of 198x198; in this way, computational

performance is optimized by evaluating images of the

same dimensions.

2.3 Attention-Based U-Net++,

Self-Supervised STEGO

Framework and Segmentation

Vision Transformer

Here, we propose a novel DL architecture, namely the

attention-based U-Net++, comprising the attention

mechanism along the spectral dimension and the

well-known U-Net++ architecture along the spatial

frame. In recent years, transformer-based

architectures have proven themself worthy of

investigation in vision contexts (Shamshad et al.,

2023).

Following data preparation, we used the attention-

based U-Net++ inside the STEGO (Self-supervised

Transformer with Energy-based Graph

Optimization), a novel framework that distils

unsupervised features into high-quality discrete

semantic labels (Hamilton et al., 2022). We carefully

modified the algorithmic structure, developed from

scratch in MATLAB 2022a (MathWorks, CA, USA),

to receive the GB HS images as input. It extracts the

features from the backbone architecture, the U-Net++

path, and later retains the segmentation results

Segmentation of Intraoperative Glioblastoma Hyperspectral Images Using Self-Supervised U-Net++

635

corresponding to the selected image characteristics

(Fig. 2-b). After that, by adopting a contrastive

learning methodology, the network can learn feature

correspondences in an unsupervised fashion. In fact,

the STEGO core yields a novel contrastive loss

function (Fig. 2-b) designed to encourage features to

form compact clusters while preserving their

relationships across the entire dataset (Hamilton et al.,

2022). In the STEGO framework, the 15 images with

their ground truth have been used for training.

Successively, an unsupervised training has been

performed on the 11 HSI images without ground truth

to derive the loss function. In this phase, the resulting

loss is the summation of the loss output contributions

obtained from the KNN, self and Random loss

functions (Fig. 2-c).

The last step is the inference, where we modified

the U-Net++ standard architecture, designing an

additional parallel path to analyse the spectral

signatures of the HS image after a first pooling step,

set to reduce the networks' parameters (Fig. 2-d).

Hence, we merged the attention-based neural path

and the U-Net++, averaging their outcomes. More

specifically, we implemented a combination of U-

Net++ and a completely trainable vision transformer

(ViT), used to improve the backbone network’s

predictions (Fig. 2-d). Here, the self-supervised

learning to calculate the loss function extracts

features from both the U-Net++ backbone network

(invariant throughout the training phase, allowing to

obtain coherent characteristics even from diverse

images) and the segmentation, represented by the

entire hybrid network (Hamilton et al., 2022). In such

an application, the segmentation part keeps

parameters fixed only in the first step of the training

so that both networks can run in parallel without

affecting the previous training done with tagged

images. In this phase, the 15 ground-truth maps and

their corresponding HS images have been used (as

well as inputs to the STEGO framework).

The networks were trained using a desktop PC

with Windows 10 SO and Intel processor Core i9-

9900X with 3.5 GHz, 128 GB RAM DDR4 with 2667

MHz working frequency, 2 NVIDIA GPUs GeForce

RTX 2080, each with 8 GB of dedicated memory.

Fifteen images were employed for both STEGO

framework and inference, with dimensions of

198×198 pixels × 128 bands, because they showed

both ground-truth for all the classes and were

conformant with the synthetic RGB image. The

HELICoiD framework results were processed by

deleting wrong point classifications to smoothen the

areas. 11 additional HS images with the same

dimensions but without their ground truths have been

used for the unsupervised training, thus leaving one

image to test the entire method.

Since the available data (especially in terms of

pixels) is not sufficient to allow for a purely supervised

approach, data augmentation through the application of

an augmenter function has been done to perform

transformations able to generate additional images. In

particular, spectral noise, global salt and pepper noise,

affine transformations and spectral bands substitutions,

as well as their options management, were applied. In

this way, for each image a series of configurations are

provided together with their occurrence probability,

thus increasing data variability.

Due to the different spatial dimensions between

the images in the database, a sub portion has been

selected as a trade-off between the amount of

information and hardware constraints. In the UNet++

architecture, a series of convolutions is performed:

the first has 128 filters, while successive blocks

employ, respectively, 64, 128, 256, 512 and 1024

convolutions. These are followed by an oversampling

that brings back the original spatial dimensions, with

the number of filters kept constant while their

execution order is inverted, and the last convolutional

layer has the same number of filters as the final

number of classes in the image, that is 4.

The drop out layer has always the same

probability value of 0.5 and the final part of the

network, represented by the combination of softmax

and classification layers.

The first sampling layer of ViT employs an 8×8

window, further changing spatial dimensions to 24×24,

while patches are extracted through a 1×1 window to

select single spectral signatures forcing the network to

focus on the spectral dimension. Such patches are then

projected to have an embedded dimension of 256

(twice the initial number of bands). Four transformer

encoding blocks were used with 8 heads by the

attention layer, whereas the MLP layer projects data

with double their dimensions, hence returning, as

output, the same dimensions of the input. Lastly, all

drop out layers have 0.4 as probability value.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

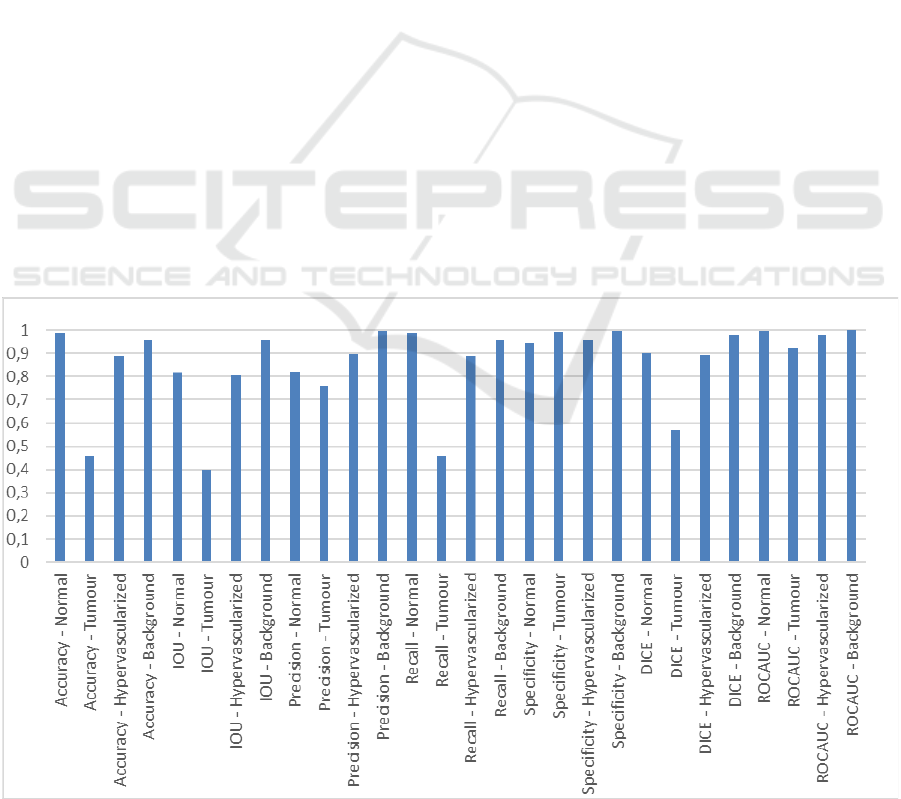

We evaluated the outcomes both quantitatively (as

shown in Fig. 3) and qualitatively concerning the

results retrieved from the HELICoiD dataset, since it

represents the safest and most honest way of

performance assessment. Fig. 3 exhibits the set of

evaluation metrics considered in this study.

Qualitatively, concerning the hypervascularized

tissue, the self-supervised architecture proposed in

VISAPP 2025 - 20th International Conference on Computer Vision Theory and Applications

636

this study can precisely outline this class. In addition,

although the attention-based U-Net++ retains suitable

specificity, recall and accuracy concerning the

tumour class, it yields improvable results for the

normal class. In fact, even though data augmentation

has been performed, the explanation of this

performance is due to the still small number of images

available, resulting in the architecture misclassifying

the background, or wrongly detecting normal

signatures as malignant ones. This issue will be

solved without changing the model architecture when

a bigger dataset is conceived.

Furthermore, we measured competitive inference

times compared to the standard CUDA environment

offered by MATLAB 2022a, hence without a custom

implementation, concerning the HELICoiD

processing times. HELICoiD’s fastest parallel and

best optimized version took 1.68 s to elaborate the

largest image of the database employing a GPU

(Florimbi et al., 2020), whilst our methodology

performs segmentation inference in 6.73 ± 2.58 s,

thoroughly satisfying the real-time constraint

imposed by the intraoperative HS acquisition system

used in the HELICoiD project, which acquired the

images in less than 80 s (Fabelo et al., 2018).

In the case of the hybrid network (combination of

ViT and U-Net++), a first training has been

performed to obtain baseline values, followed by the

self-supervised framework. The first part is divided

into four steps:

1. U-Net++ and ViT pre-training,

2. supervised training, through the adoption of the

STEGO framework, of the single nets for

segmentation purposes,

3. tumours’ segmentation by training of all

networks (through substitution of the last layer

with a weighted classification one to discriminate

the error contribution among all classes of the

entire dataset) and loss function calculus through

unsupervised learning combining the

contributions of KNN, self and random loss

functions,

4. self-supervised training of the attention-based U-

Net++.

Performance of the trained network has been

evaluated on the entire dataset of 27 images through

self-supervised learning and compared to statistical

metrics derived from the confusion matrix (Fig. 4):

accuracy, precision, recall, DICE similarity

coefficient, F1 score, Intersection over Union (IoU)

and ROC’s Area Under Curve (AUC).

4 CONCLUSIONS

In this work we investigated a novel DL methodology

targeting the end-to-end semantic segmentation of

hyperspectral images belonging to the HELICoiD

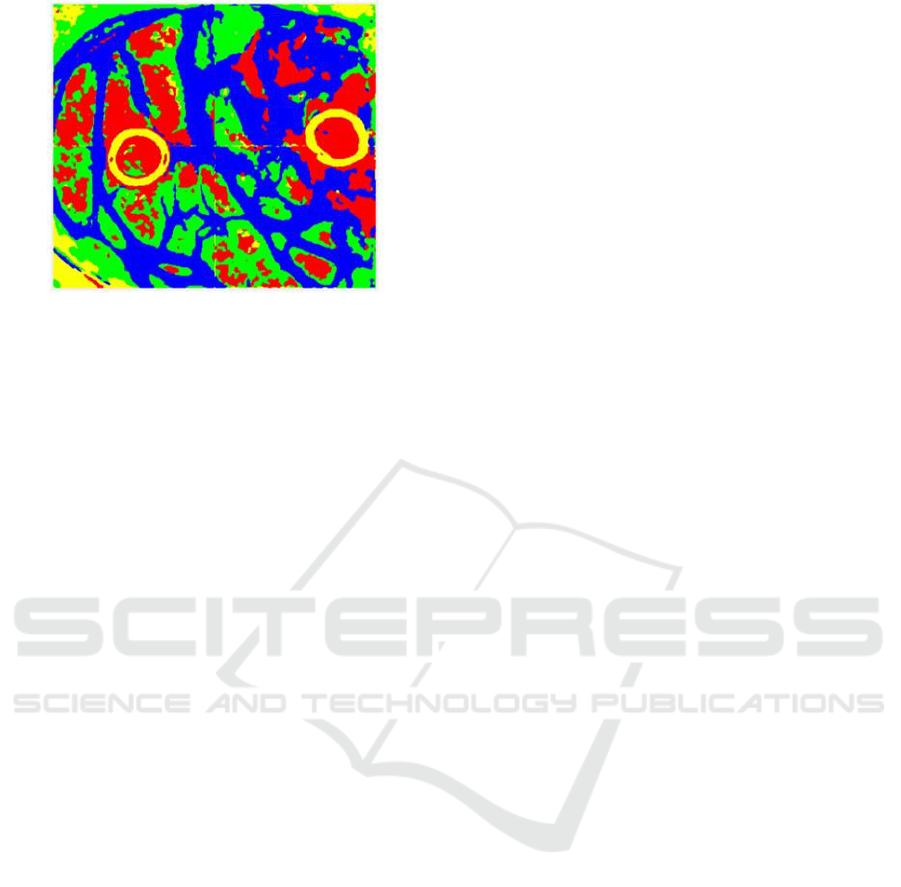

Figure 3: Hybrid network segmentation results.

Segmentation of Intraoperative Glioblastoma Hyperspectral Images Using Self-Supervised U-Net++

637

Figure 4: Example of the segmentation output for a test

image undergoing self-supervised learning. The tumour is

shown in red, while the background is in yellow.

Hypervascularized tissue is in blue and normal tissue is in

green.

dataset. Namely, we researched a self-supervised

algorithm to train an innovative segmentation

architecture. The proposed methodology allows the

end-to-end segmentation of such images, targeting

real-time processing to be employed during open

craniotomy in surgery.

This innovative approach improves the gold-

standard HELICoiD pipeline and it offers competitive

results in terms of classification. We measured

competitive inference results for the identification of

unhealthy tissue, namely exceeding 90% in

specificity and recall. Nonetheless, the framework

exhibits poor performance when the architecture

classifies normal and background image portions as

tumour.

On the other hand, this is an open research topic

which we aim to improve and clarify in further works.

We believe the proposed SSL methodology could

refine medical HS image segmentation, thus brushing

up state of the art computer-aided diagnostic systems.

A further improvement will be the evaluation of our

approach considering broader datasets, including a

higher number of images, potentially coming from

different brain tumours, thus obtaining a general

diagnostic tool.

The proposed methodology could enhance

medical hyperspectral research overcoming labelling

and dataset size challenges.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by the Spanish

Government and European Union (FEDER funds) in

the context of TALENT-HExPERIA project, under

the contract PID2020-116417RB-C42

AEI/10.13039/501100011033.

REFERENCES

Bray, F., Laversanne, M., Sung, H., Ferlay, J., Siegel, R.

L., Soerjomataram, I., & Jemal, A. (2024). Global

cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of

incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in

185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians,

74(3), 229–263. doi: 10.3322/caac.21834

Collins, T., Maktabi, M., Barberio, M., Bencteux, V.,

Jansen-Winkeln, B., Chalopin, C., Marescaux, J.,

Hostettler, A., Diana, M., & Gockel, I. (2021).

Automatic Recognition of Colon and Esophagogastric

Cancer with Machine Learning and Hyperspectral

Imaging. Diagnostics, 11(10), 1810. doi:

10.3390/diagnostics11101810

Fabelo, H., Ortega, S., Kabwama, S., Callico, G. M.,

Bulters, D., Szolna, A., Pineiro, J. F., & Sarmiento, R.

(2016). HELICoiD project: a new use of hyperspectral

imaging for brain cancer detection in real-time during

neurosurgical operations (D. P. Bannon, Ed.; p.

986002). doi: 10.1117/12.2223075

Fabelo, H., Ortega, S., Lazcano, R., Madroñal, D., M.

Callicó, G., Juárez, E., Salvador, R., Bulters, D.,

Bulstrode, H., Szolna, A., Piñeiro, J., Sosa, C., J.

O’Shanahan, A., Bisshopp, S., Hernández, M., Morera,

J., Ravi, D., Kiran, B., Vega, A., … Sarmiento, R.

(2018). An Intraoperative Visualization System Using

Hyperspectral Imaging to Aid in Brain Tumor

Delineation. Sensors, 18(2), 430. doi:

10.3390/s18020430

Fabelo, H., Ortega, S., Szolna, A., Bulters, D., Pineiro, J.

F., Kabwama, S., J-O’Shanahan, A., Bulstrode, H.,

Bisshopp, S., Kiran, B. R., Ravi, D., Lazcano, R.,

Madronal, D., Sosa, C., Espino, C., Marquez, M., De

La Luz Plaza, M., Camacho, R., Carrera, D., …

Sarmiento, R. (2019). In-Vivo Hyperspectral Human

Brain Image Database for Brain Cancer Detection.

IEEE Access, 7, 39098–39116. doi:

10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2904788

Florimbi, G., Fabelo, H., Torti, E., Ortega, S., Marrero-

Martin, M., Callico, G. M., Danese, G., & Leporati, F.

(2020). Towards Real-Time Computing of

Intraoperative Hyperspectral Imaging for Brain Cancer

Detection Using Multi-GPU Platforms. IEEE Access,

8, 8485–8501. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2963939

Girardi, F., Matz, M., Stiller, C., You, H., Marcos Gragera,

R., Valkov, M. Y., Bulliard, J.-L., De, P., Morrison, D.,

Wanner, M., O’Brian, D. K., Saint-Jacques, N.,

Coleman, M. P., Allemani, C., Bouzbid, S., Hamdi-

Chérif, M., Kara, L., Meguenni, K., Regagba, D., …

Lewis, C. (2023). Global survival trends for brain

tumors, by histology: analysis of individual records for

556,237 adults diagnosed in 59 countries during 2000–

2014 (CONCORD-3). Neuro-Oncology, 25(3), 580–

592. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noac217

VISAPP 2025 - 20th International Conference on Computer Vision Theory and Applications

638

Halicek, M., Fabelo, H., Ortega, S., Callico, G. M., & Fei,

B. (2019). In-Vivo and Ex-Vivo Tissue Analysis

through Hyperspectral Imaging Techniques: Revealing

the Invisible Features of Cancer. Cancers, 11(6), 756.

doi: 10.3390/cancers11060756

Hamilton, M., Zhang, Z., Hariharan, B., Snavely, N., &

Freeman, W. T. (2022). Unsupervised Semantic

Segmentation by Distilling Feature Correspondences.

Jansen-Winkeln, B., Barberio, M., Chalopin, C., Schierle,

K., Diana, M., Köhler, H., Gockel, I., & Maktabi, M.

(2021). Feedforward Artificial Neural Network-Based

Colorectal Cancer Detection Using Hyperspectral

Imaging: A Step towards Automatic Optical Biopsy.

Cancers, 13(5), 967. doi: 10.3390/cancers13050967

Kumar, D., & Kumar, D. (2021). Hyperspectral Image

Classification Using Deep Learning Models: A

Review. Journal of Physics: Conference Series,

1950(1), 012087. doi: 10.1088/1742-

6596/1950/1/012087

La Salvia, M., Torti, E., Gazzoni, M., Marenzi, E., Leon,

R., Ortega, S., Fabelo, H., Callicó, G., & Leporati, F.

(2023). AI-based segmentation of intraoperative

glioblastoma hyperspectral images. N. J. Barnett, A. A.

Gowen, & H. Liang (Eds.), Hyperspectral Imaging and

Applications II (p. 12). SPIE. doi: 10.1117/12.2646782

Leon, R., Fabelo, H., Ortega, S., Piñeiro, J. F., Szolna, A.,

Hernandez, M., Espino, C., O’Shanahan, A. J.,

Carrera, D., Bisshopp, S., Sosa, C., Marquez, M.,

Morera, J., Clavo, B., & Callico, G. M. (2021). VNIR–

NIR hyperspectral imaging fusion targeting

intraoperative brain cancer detection. Scientific

Reports, 11(1), 19696. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-

99220-0

Louis, D. N., Perry, A., Wesseling, P., Brat, D. J., Cree, I.

A., Figarella-Branger, D., Hawkins, C., Ng, H. K.,

Pfister, S. M., Reifenberger, G., Soffietti, R., von

Deimling, A., & Ellison, D. W. (2021). The 2021

WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous

System: a summary. Neuro-Oncology, 23(8), 1231–

1251. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noab106

Lu, G., & Fei, B. (2014). Medical hyperspectral imaging:

a review. Journal of Biomedical Optics, 19(1), 010901.

doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.19.1.010901

Salvia, M. La, Torti, E., Gazzoni, M., Marenzi, E., Leon,

R., Ortega, S., Fabelo, H., Callico, G. M., & Leporati,

F. (2022). Attention-based Skin Cancer Classification

Through Hyperspectral Imaging. 2022 25th Euromicro

Conference on Digital System Design (DSD), 871–

876. doi: 10.1109/DSD57027.2022.00122

Shamshad, F., Khan, S., Zamir, S. W., Khan, M. H., Hayat,

M., Khan, F. S., & Fu, H. (2023). Transformers in

medical imaging: A survey. Medical Image Analysis,

88, 102802. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2023.102802

Torti, E., Gazzoni, M., Marenzi, E., Leon, R., Callicò, G.

M., Danese, G., & Leporati, F. (2023). An Attention-

Based Parallel Algorithm for Hyperspectral Skin

Cancer Classification on Low-Power GPUs. 2023 26th

Euromicro Conference on Digital System Design

(DSD), 111–116. doi:

10.1109/DSD60849.2023.00025

Wang, Y., Albrecht, C. M., Braham, N. A. A., Mou, L., &

Zhu, X. X. (2022). Self-Supervised Learning in

Remote Sensing: A review. IEEE Geoscience and

Remote Sensing Magazine, 10(4), 213–247. doi:

10.1109/MGRS.2022.3198244

Yue, J., Fang, L., Rahmani, H., & Ghamisi, P. (2022). Self-

Supervised Learning With Adaptive Distillation for

Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE

Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 60,

1–13. doi: 10.1109/TGRS.2021.3057768

Zhu, M., Fan, J., Yang, Q., & Chen, T. (2022). SC-

EADNet: A Self-Supervised Contrastive Efficient

Asymmetric Dilated Network for Hyperspectral Image

Classification. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and

Remote Sensing, 60, 1–17. doi:

10.1109/TGRS.2021.3131152

Segmentation of Intraoperative Glioblastoma Hyperspectral Images Using Self-Supervised U-Net++

639