Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches for Early

Alzheimer’s Detection in Patients with Subjective Cognitive Decline:

A Systematic Literature Review

Zyad Taouil

a

, Nourhène Ben Rabah and Bénédicte Le Grand

Centre de Recherche en Informatique, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, Paris, France

Keywords: Machine Learning, Alzheimer's Disease, Subjective Cognitive Decline, Detection, Biomarker, Classification.

Abstract: This paper investigates the application of machine learning and deep learning techniques for the early

detection of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) in patients with Subjective Cognitive Decline (SCD), a preclinical

AD stage. Traditional diagnosis methods struggle to detect AD at this stage, making ML a promising

alternative for early intervention. A systematic literature review (SLR) was conducted to identify and analyze

the most effective ML models, data types, and preprocessing techniques for early AD detection. This review

highlights that Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), Random Forest, and logistic regression models,

particularly when applied to multimodal data (e.g., neuroimaging, genetic, and vocal features), showing high

diagnosis accuracy. Data preprocessing steps such as feature engineering and data augmentation significantly

enhance model performance. This paper also explores the practical implications of implementing ML models

in clinical settings and discusses system integration, clinician training, and ethical considerations surrounding

patient data. This research emphasizes the potential of ML to enhance early AD diagnosis.

1 INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is a progressive

neurodegenerative disorder that currently affects

millions of people worldwide, representing one of the

most significant public health challenges as

populations age. Traditionally, AD diagnosis relies

on clinical assessments and neuroimaging, but these

methods show limitations regarding the detection of

the disease at its earliest stages, particularly during

the preclinical phase known as Subjective Cognitive

Decline (SCD). SCD is characterized by self-reported

memory or cognitive issues (RABIN, 2017), and has

been recognized as a precursor to Mild Cognitive

Impairment and full-blown AD.

Despite the gravity of this global public health

challenge, the early diagnosis of AD remains

difficult. Many clinical tests are insufficiently

sensitive to mild changes in cognition, and advanced

imaging or biomarker analyses may not be accessible

in all healthcare settings. Consequently, there is a

critical unmet need for more cost-effective, scalable,

and accurate diagnostic methods to identify at-risk

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-1607-9872

individuals before irreversible neuronal damage

occurs. The potential benefits of such research are

substantial: earlier interventions may slow disease

progression, reduce healthcare costs, and improve

patients’ quality of life.

Moreover, detecting AD at this early stage could

be crucial for preventive treatments, thereby

mitigating the disease’s progression. In recent years,

Innovative applications of Machine Learning (ML)

and Deep Learning has shown great potential for

transforming medical diagnosis, particularly in areas

involving complex data such as neuroimaging,

genetic information, and cognitive assessments.

However, despite the progress made, the application

of ML to AD diagnosis in the preclinical stage,

specifically for individuals showing signs of SCD,

remains underexplored.

The central problem addressed in this study is how

machine learning and deep learning models can be

used to improve the early detection of AD in patients

with SCD, enhancing detection accuracy and

providing opportunities for earlier, more effective

interventions. Early diagnosis through ML and deep

598

Taouil, Z., Ben Rabah, N. and Grand, B. L.

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches for Early Alzheimer’s Detection in Patients with Subjective Cognitive Decline: A Systematic Literature Review.

DOI: 10.5220/0013247600003890

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART 2025) - Volume 2, pages 598-610

ISBN: 978-989-758-737-5; ISSN: 2184-433X

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

learning not only has the potential to improve the

identification of at-risk individuals based on slight

variations in biomarkers such as neuroimaging,

genetic markers, or behavioral data but also opens the

door to more targeted inclusion of individuals in

clinical trials aimed at slowing or preventing the

progression of the disease.

This paper aims to answer three key research

questions:

RQ1. What are the most effective ML models for

diagnosing AD at the preclinical stage?

RQ2. How do different types of data and

preprocessing techniques affect the performance

of these models?

RQ3. What are the practical implications of

integrating ML models into clinical settings for

early AD diagnosis?

To address these research questions, we

conducted a systematic literature review, focusing on

the application of ML techniques in the context of

Subjective Cognitive Decline and Alzheimer’s

Disease diagnosis. Then we examined the

performance of various ML models, the impact of

different data types and preparation techniques, and

the challenges involved in bringing these models into

clinical practice.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2

provides the background of the subject and critically

reviews prior literature reviews that have addressed

it. Section 3 describes in detail the methodology used

to conduct the systematic literature review. Section 4

presents the results, addressing the different research

questions: (RQ1) focuses on analyzing the most

effective ML models, (RQ2) explores the types of

data and preprocessing techniques identified, and

(RQ3) examines the practical implications of

integrating machine learning models into clinical

settings for the early diagnosis of Alzheimer's

disease. Section 5 discusses the challenges

encountered and the research gaps identified. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the study and suggests directions

for future work.

2 BACKGROUND AND

RELATED WORKS

In this section, we present the background of the

subject and review the literature reviews that have

addressed this topic in previous years. This

comparative analysis allows us to highlight the

originality of our systematic literature review by

showing how our approach differs from previous work

and providing new perspectives on the field of study.

2.1 Background

At the forefront of AD research and clinical practice

lies the preclinical stage of the disease. This stage is

characterized by “no impairment in cognition on

standard assessments and biomarker evidence for

AD” (JESSEN, 2014). Detecting AD at this stage

provides a critical opportunity for intervention, as

therapeutic treatments applied before significant

cognitive decline may delay or even prevent the

progression to symptomatic stages such as Mild

Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and full dementia.

This approach reflects a significant shift in AD

research, moving the focus from treating advanced

stages of the disease to identifying and intervening at

its earliest, asymptomatic phase.

Subjective Cognitive Decline as a Key

Indicator: Within the preclinical phase, Subjective

Cognitive Decline has emerged as a critical focus

area. Studies have shown that individuals with SCD

are at higher risk of developing AD-related cognitive

impairments in the future, as many of them already

exhibit biological changes associated with AD, such

as elevated levels of amyloid-beta and tau proteins,

two key biomarkers of the disease (RABIN, 2017).

Given the association between SCD and these

biomarkers, SCD represents a valuable early indicator

for AD research. Individuals reporting SCD may

serve as an ideal target population for preclinical

screening, as detecting biological markers before the

appearance of clinical symptoms could provide a

crucial window for therapeutic intervention.

Moreover, SCD provides a practical and cost-

effective approach to identifying at-risk individuals,

helping streamline clinical trials and the development

of targeted treatment strategies.

Machine Learning as a Detection Tool:

Traditional detection tools for AD, such as

neuroimaging and biomarker tests, often require

advanced medical facilities, making them costly and

inaccessible to a broader population. In response,

Machine Learning has emerged as a promising

solution. Indeed, ML algorithms excel in identifying

subtle patterns within complex datasets, such as those

generated from neuroimaging or biomarker analysis.

By analyzing vast amounts of multimodal data, ML

algorithms have demonstrated remarkable potential

in distinguishing early-stage AD from healthy aging

with high accuracy. This has the potential to

revolutionize early diagnosis and treatment by

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches for Early Alzheimer’s Detection in Patients with Subjective Cognitive Decline: A

Systematic Literature Review

599

enabling personalized interventions that are more

precise and timelier.

ML models typically used in AD research include

classification and regression algorithms.

Classification models are designed to categorize data

into predefined classes, such as distinguishing

between individuals with AD and cognitively

unimpaired individuals (Kingsmore, 2021).

Regression models, on the other hand, analyze the

relationship between a dependent variable and one or

more independent variables and are used to predict

continuous outcomes (Horenko, 2023), such as the

progression of cognitive decline or biomarker levels.

Both types of models play a critical role in developing

more accurate detections.

2.1.1 Key Definitions

Preclinical Stage: The phase of Alzheimer’s Disease

where there is biomarker evidence for AD but no

detectable cognitive decline in standard clinical tests

(Jessen, 2014).

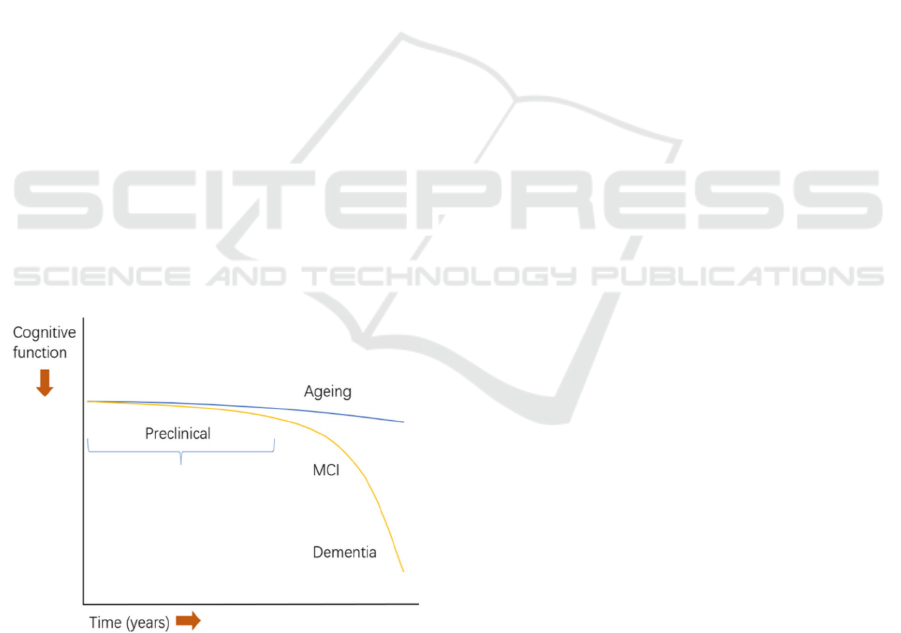

This curve illustrates the typical progression of

cognitive function over time about aging and the

onset of Alzheimer's Disease. AD is depicted with the

yellow line where it starts with the preclinical stage

which occurs before the MCI stage, “the symptomatic

predementia phase of AD” (Rabin, 2017), before

evolving, with a quick cognitive decline to dementia,

“a chronic and progressive deterioration disease

characterized by cognitive dysfunction and abnormal

mental behavior” (Shen, 2018).

Figure 1: Model of the cognitive function decline trajectory

of AD vs normal ageing (Huang, 2023).

Biomarkers: Biological indicators, such as

amyloid-beta and tau proteins, found in blood, brain

images, or cerebrospinal fluid, which provide

evidence of Alzheimer’s pathology before clinical

symptoms manifest. A “large number of clinical

studies very consistently show that these biomarkers

contribute with diagnostically relevant information,

also in the early disease stages”. (Blennow, 2018)

Single-Modal vs. Multimodal ML Approaches:

A key distinction in ML approaches for AD diagnosis

is between single-modal and multimodal data

analysis. Single-modal models analyze data from one

source, such as MRI scans, while multimodal models

integrate data from multiple sources (e.g.,

neuroimaging, biomarkers, and cognitive tests)

(REN, 2022).

2.2 Previous Literature Reviews

We identified two review papers that addressed

Alzheimer's disease (AD) diagnosis using machine

learning (ML) and deep learning techniques. We

presented these studies and highlighted the

contribution of our work in comparison to them.

2.2.1 Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis Using

Machine Learning: A Survey

(Dara, 2023)

This extensive survey reviews over 80 publications

from 2017 onwards, with a focus on "fundamental

machine learning architectures such as support vector

machines, decision trees, and ensemble models." The

study provides an overview of traditional ML models,

such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs), decision

trees, and ensemble methods, all of which have been

widely used in diagnosing AD by analyzing

neuroimaging and non-imaging biomarkers.

It highlights that deep learning models,

particularly CNN, have demonstrated superior

performance in handling complex neuroimaging data,

extracting features, and classifying AD with high

accuracy. Moreover, this survey highlights the need

for improved model interpretability, particularly for

deep learning models like CNN, which often function

as a "black box" in clinical contexts. The lack of

transparency in these models poses a significant

barrier to their widespread clinical adoption,

especially in the diagnosis of early-stage AD where

explainability is critical for clinician trust and

decision-making.

While this survey provides a broad overview of

ML technologies in AD diagnosis, it lacks a specific

focus on the preclinical stage of Alzheimer’s Disease.

The majority of the reviewed studies focus on

later stages of AD, such as MCI and fully developed

AD, which are symptomatic phases of the disease. As

a result, this survey does not fully capture the

potential of ML to detect AD at the preclinical stage,

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

600

when interventions could have the most significant

impact. Additionally, the review does not delve into

the technical steps of ML implementations, such as

data preprocessing, hyperparameter tuning, or the

challenges of working with different types of data.

These elements are crucial for understanding how ML

models can be optimized for early-stage AD

detection.

2.2.2 Systematic Review on Machine

Learning and Deep Learning

Techniques in the Effective Diagnosis

of Alzheimer’s Disease (Arya, 2023)

This systematic review focuses on the use of machine

learning methods, such as Random Forest (RF),

SVMs, and Logistic Regression, to classify patients

as cognitively normal or suffering from AD.

This review puts significant emphasis on imaging

modalities, particularly Positron Emission

Tomography (PET) and Magnetic Resonance

Imaging (MRI), for detecting AD-related changes in

the brain. The authors argue that deep learning

methods for feature extraction, combined with

traditional ML models like SVMs for classification,

are highly efficient in diagnosing AD.

Though the study provides valuable insights into

the application of ML for AD diagnosis, its focus

remains largely on symptomatic patients rather than

those in the preclinical stage. The omission of SCD

as a critical marker for early detection leaves a gap in

understanding how ML can be applied to detect AD

before a significant cognitive decline occurs.

Furthermore, the study is heavily focused on

neuroimaging, particularly PET and MRI scans,

which, while important, do not fully capture the range

of potential detection tools and data types. Other non-

invasive biomarkers, such as vocal features, genetic

data, or cognitive test results, are underexplored in

this review.

2.2.3 Contribution of Our Work

The research gaps identified in the studies underscore

the importance of focusing on the preclinical stage of

Alzheimer’s Disease AD, when early intervention

may be most effective. Unlike these broad reviews,

our research specifically targets the preclinical stage,

aiming to harness ML techniques to detect the earliest

signs of cognitive decline, particularly in individuals

reporting SCD. By focusing on this critical phase of

the disease, we aim to contribute to the growing body

of work that seeks to enable early diagnosis and

intervention through Machine Learning. Our work

also distinguishes itself by incorporating a more

detailed computer science perspective. We provide a

deeper analysis of the ML implementations, including

the specificities of different algorithms, their data

dependencies, and the importance of data

preprocessing. In fact, preprocessing techniques, such

as feature selection, data augmentation, and handling

of missing data, are often overlooked but are crucial

to the performance of ML models in medical

diagnostics. By addressing these technical aspects,

we offer a comprehensive understanding of how ML

can be effectively integrated into the early detection

process for Alzheimer’s Disease.

Moreover, our study explores the use of

multimodal data, integrating neuroimaging, genetic,

speech and linguistic data to improve the performance

of ML models. While previous studies have primarily

focused on single-modal approaches (e.g., MRI or

PET scans), our research investigates the synergistic

effects of combining multiple data types to enhance

diagnostic accuracy and reliability. This approach is

particularly important for detecting early-stage AD,

where symptoms are minimal, and a single data

source may not provide sufficient information for an

accurate diagnosis.

Furthermore, we emphasize the need for

explainable AI (XAI) models in clinical settings,

ensuring that machine learning models not only

perform well statistically but also provide actionable

insights that clinicians can trust and implement in

their decision-making processes. By focusing on the

explainability of ML models, our work aims to bridge

the gap between technological advancements and

clinical applicability, ensuring that the developed

models can be realistically integrated into healthcare

settings.

3 METHODOLOGY

To conduct this research, we followed the

Kitchenham methodology, formally known as the

"Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature

Reviews in Software Engineering" (KITCHENHAM,

2007). This framework, originally developed for

software engineering research, is highly suitable for a

review involving ML technologies applied to medical

diagnosis. We also refer to Kitchenham's

complementary work, "Procedures for Performing

Systematic Reviews" (Kitchenham, 2004), for

detailed guidance on each step of the methodology.

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches for Early Alzheimer’s Detection in Patients with Subjective Cognitive Decline: A

Systematic Literature Review

601

3.1 Planning

3.1.1 PICOC Framework

We employed the PICOC (Population, Intervention,

Comparison, Outcome, Context) criteria to formulate

the research questions:

Population (P). Cognitively unimpaired

individuals diagnosed as healthy controls (HC)

or with SCD.

Intervention (I). Application of ML and/or DL

techniques to detect early AD.

Comparison (C). Various ML models tested

Outcome (O). Diagnosis performance metrics

like accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, F1-score,

and AUC-ROC.

Context (C). Academic research environments

utilizing diverse datasets (e.g., neuroimaging,

genetic, clinical records).

3.1.2 Research Questions

Using the PICOC framework, we formulated the

three research questions outlined in the introduction.

3.1.3 Keywords and Search String

This search string allowed us to collect 81 articles in

February 2024.

“("Machine learning" OR "machine-learning" OR

"Deep learning" OR "deep-learning") AND

"Alzheimer" AND (diagnosis OR detect OR predict)

AND (preclinical OR "Subjective Cognitive Decline"

OR "Subjective Cognitive Impairment" OR

"Subjective Memory Disorder")”

3.1.4 Sources

We sourced the literature primarily from Scopus,

accessing a variety of publications, including

PubMed, IEEE Xplore, and ScienceDirect.

3.1.5 Inclusion/ Exclusion Criteria

We then applied inclusion and exclusion criteria to

retain only the relevant papers.

Inclusion criteria:

- Studies focusing on ML applications in

diagnosing AD at the preclinical stage.

- Experimental research involving diverse

populations and biomarkers.

- Studies published after 2021 to reflect the most

recent advancements.

Exclusion criteria:

- Studies not written in English.

- Studies focusing on later stages of AD (MCI or

dementia) or that did not use ML models.

3.2 Conducting

3.2.1 Study Selection

After running the query, we filtered the articles using

the inclusion/exclusion criteria resulting in 38 papers,

where at last 28 were selected, after complete reading

of the articles.

3.2.2 Data Extraction

A data extraction table was used to synthesize

relevant data across studies. Key elements included:

- ML Algorithms: Specific algorithms used (e.g.,

SVM, CNN).

- Data Types: Neuroimaging, biomarker data,

cognitive tests.

- Preprocessing: Techniques like data cleaning,

scaling, feature selection.

- Performance Metrics: Accuracy, sensitivity,

specificity, F1-score.

This structured approach provided a basis for

quantitative and qualitative analysis.

3.3 Tools

We used Parsifal for systematic review management

(Parsifal) and Zotero (Zotero) to organize articles by

tags and track citation metrics, publication dates, and

references.

By employing this structured methodology, we

ensured that our review covered the most relevant and

high-quality studies on ML applications for

diagnosing Alzheimer's Disease at the preclinical

stage, focusing particularly on SCD.

4 RESULTS

Figure 2 shows the number of papers from the SLR

that are used to answer our three research questions.

Figure 2: Usage of papers throughout SLR.

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

602

4.1 What Are the Most Effective

Machine Learning Models for

Diagnosing Alzheimer's Disease at

the Preclinical Stage? (RQ1)

All selected studies (28) contributed to answering our

first research question, highlighting the following key

ML models: Convolutional Neural Network

(CNN), Random Forest (RF), Logistic Regression

(LR), and Support Vector Machines (SVM). Each

algorithm's specific characteristics and their

performance in AD diagnosis are discussed below.

4.1.1 Most Used Machine Learning

Algorithms

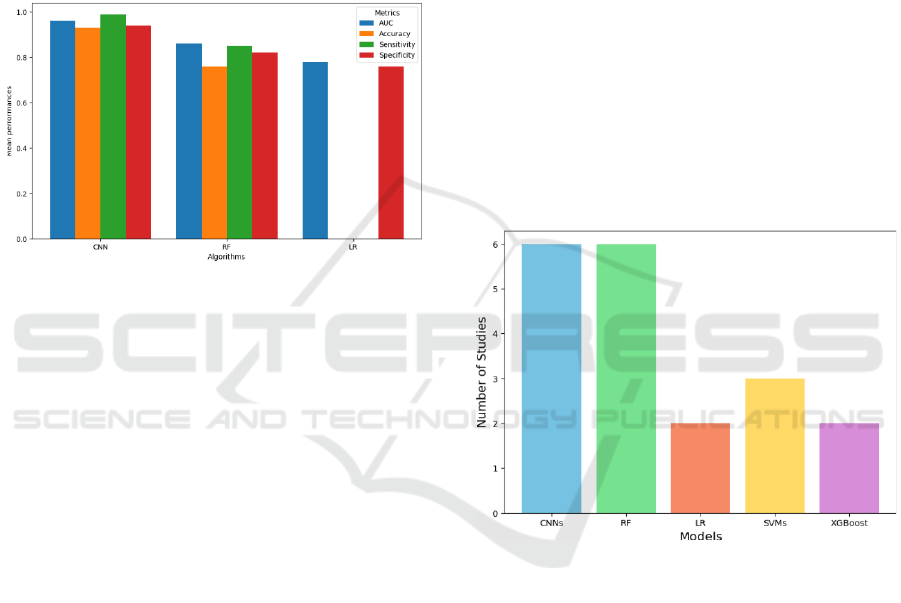

As depicted in Figure 3, CNN emerged as the most

frequently used algorithm, appearing in 12 studies.

CNN are highly effective for neuroimaging tasks

(e.g., MRI, and PET scans) due to its ability to extract

spatial features from high-dimensional image data

(SONG, 2020). However, CNN lacks explainability

(Mattia, 2021) and requires high computational

resources (Logan, 2021), which can limit its clinical

applicability.

Figure 3: Most used ML algorithms in AD classification.

RF appeared 11 times and is characterized by its

robustness to overfitting and its ability to handle

multimodal data (neuroimaging, cognitive, and

genetic) (Sarica, 2017). RF models are particularly

useful in scenarios where diverse datasets need to be

integrated. However, like CNN, RF models suffer from

low interpretability, though tools like SHAP values can

partially mitigate this issue (Avraam, 2023).

LR, used in 8 studies, is appreciated for its

simplicity and transparency, making it suitable for

binary classification tasks (e.g., disease vs. no

disease). Despite its interpretability, LR has

limitations in handling high-dimensional data and

complex relationships, which are common in AD-

related datasets (Menezes, 2017).

SVM used in 5 studies, is robust for high-

dimensional data (CHEN, 2011) and offer

explainability through kernel functions (Mandhala,

2014). However, SVM can be computationally

intensive and sensitive to parameter selection (Land,

2002).

Table 1: Used Algorithms in Literature.

Al

g

orithms References

Convolutional Neural

Network (CNN)

(MOHI UD DIN DAR,

2023), (ODUSAMI,

2022), (OKTAVIAN,

2022), (ANGKOSO,

2022), (FU’ADAH,

2021), (EBRAHIMI,

2021), (MURUGAN,

2021), (SHAMRAT,

2023),

(KIM N. H., 2023)

Random Forest (RF) (BOHN, 2023), (KIM N.

H., 2023), (CHIU, 2022),

(REN Y. S., 2023),

(SCHEIJBELER E. P.,

2022), (BAYAT, 2021),

(JANG, 2021),

(GAUBERT, 2021),

(GOUW, 2021), (KIM J.

L., 2021

)

Logistic Regression (LR) (KIM N. H., 2023),

(HAJJAR, 2023),

(JIANG, 2022), (JANG,

2021), (GAUBERT,

2021), (SHIMODA,

2021), (SCHEIJBELER

E. P., 2022

)

Support Vector Machine

(SVM)

(KIM N. H., 2023),

(CHIU, 2022), (JIANG,

2022), (GAUBERT,

2021

)

Multitask Learnin

g

(

LEI, 2021

)

XGBoost (KIM N. H., 2023),

(

SHIMODA, 2021

)

Artificial Neural Network

(ANN)

(HAJJAR, 2023)

Recurrent Neural Network

(

RNN

)

(EBRAHIMI, 2021)

K-Nearest Neighbor

(

KNN

)

(KIM N. H., 2023)

Transforme

r

(

SIBILANO, 2023

)

Extra Trees (TER HUURNE, 2023)

AdaBoost (KIM N. H., 2023)

Generative Adversial

Network

(

GAN

)

(HWANG, 2023)

Gradient Boosting

Machine

(

GBM

)

(KIM N. H., 2023)

Naïve Ba

y

es

(

KIM N. H., 2023

)

Other ensemble methods, such as AdaBoost,

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches for Early Alzheimer’s Detection in Patients with Subjective Cognitive Decline: A

Systematic Literature Review

603

XGBoost, and Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM),

appeared less frequently but holds promising results

in combining multiple weak learners (Mandhala,

2014) to improve prediction accuracy.

4.1.2 Global Performance of Algorithms

To evaluate the global performance of the 3 most

popular ML algorithms from the previous question,

namely CNN, RF and LR, we analyzed in figure 4

their mean metrics across studies, including AUC,

accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity.

Figure 4: Mean performance metrics (AUC, accuracy,

sensitivity, specificity) for CNN, RF, and LR.

In fact, in the context of classification of AD stages,

the performance of ML algorithms is typically

assessed using various metrics such as:

Accuracy which in this context “refers to the total

percentage of participants who were correctly

classified as either CU or as belonging to the targeted

clinical cohort (i.e., the fraction of true positives and

true negatives over all model classifications)”

(BOHN, 2023).

Sensitivity (or recall) “reflects the percentage of

participants from the target clinical cohort who were

correctly classified as such (calculated as true

positives / (true positives + false negatives))”

(BOHN, 2023).

Specificity (or precision) “which represents the

percentage of participants who were correctly

classified into the target clinical cohort (calculated as

true positives / (true positives + false positives))”

(BOHN, 2023).

Area Under the Curve (AUC) is “a summary

measure of the model’s ability to distinguish between

CU and the targeted clinical cohorts” (BOHN, 2023).

In the various studies reviewed, we found that

CNN, RF, and LR are the most used models. CNN

consistently outperformed other models, with a mean

AUC of 0.964 and an accuracy of 0.931 in imaging

tasks (e.g., MRI). CNN's superior image processing

capabilities make them ideal for detecting subtle

changes in brain structure at the preclinical stage. RF

achieved a mean AUC of 0.856, with strong

performance in multimodal data settings (AUC up to

0.89 (BOHN, 2023)). Indeed, RF showed good

performance across different data types, including

neuroimaging and vocal features. LR demonstrated

lower performance, with an average AUC of 0.775.

However, its simplicity and interpretability make it a

good baseline model, particularly for studies with

smaller datasets.

4.1.3 Effect of Model Tuning

14 out of the 28 studies employed model tuning (see

repartition in Figure 5), which had significant impact

on the performance of ML algorithms, especially for

Random Forest and CNN models, showing

substantial improvements when optimized through

techniques like Grid Search used in 62.5% of articles

using model tuning, Bayesian Optimization (25%)

and Incremental tuning (12.5%).

Figure 5: Repartition of algorithms using Model Tuning.

4.2 How Do Different Data Types and

Preprocessing Techniques Impact

the Performance of Machine

Learning Models in Early

Diagnosis of Alzheimer's Disease?

(RQ2)

Different types of data have been employed in the

diagnosis of AD at the preclinical stage, including

neuroimaging biomarkers, EEG, cognitive tests, and

demographic data. In the following section, we

explore the most frequent combinations of data

types with ML algorithms, the impact of data

preparation and compare standalone and multimodal

data.

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

604

4.2.1 Evaluation of Data Types

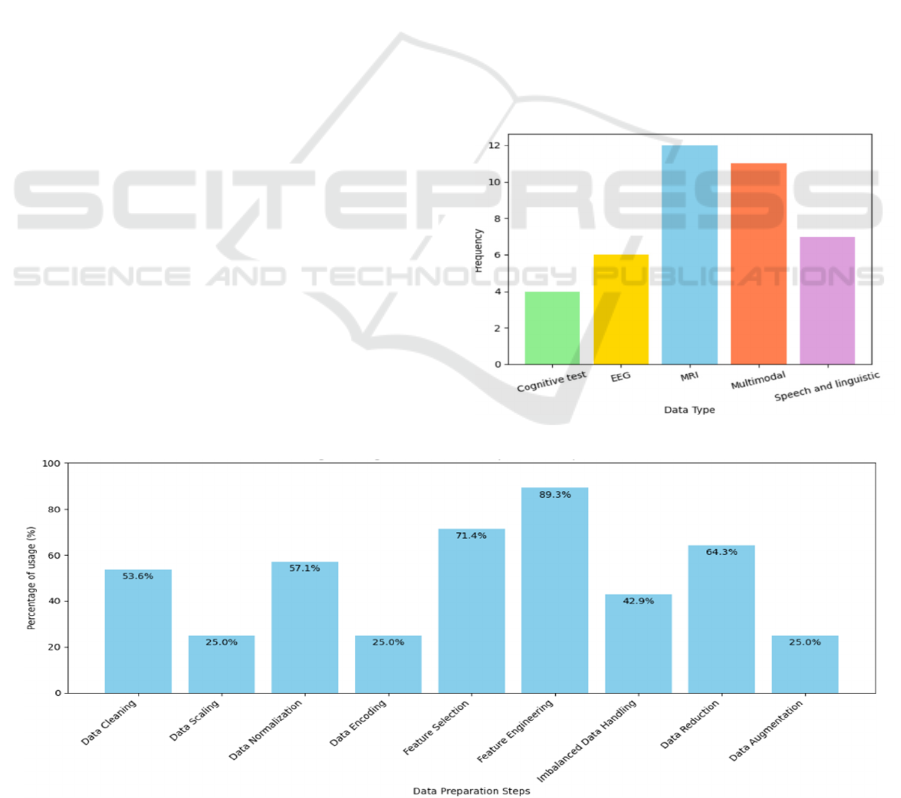

Among the reviewed papers as shown in figure 6, MRI

data stands out as the most frequently used, appearing

in 12 studies, particularly from the ADNI dataset, the

most used dataset across the papers (9 times). This

reliance on well-curated, clinical datasets like MRI

shows a preference for high-resolution imaging despite

potential limitations in generalizability to real-world,

noisier data.

Other clinical data such as EEG data (6 times) and

cognitive tests (4 times) are also used but to a lesser

extent, suggesting that although these data types are

valuable, they may lack the detailed imaging

capabilities of MRI and available open-source

datasets such as ADNI.

Multimodal approaches, which combine both

clinical and non-clinical data types, were used in 11

studies, indicating a growing interest in integrating

diverse data sources for a more comprehensive view

of early AD indicators.

Non-clinical data such as speech and linguistic

features, though explored in a few studies (5

instances), remain less common, likely due to the

challenges in data preprocessing and standardization.

4.2.2 Impact of Data Preparation and Data

Quality on Machine Learning Model

Performance

Data preparation is a crucial step in machine learning

pipelines that involves transforming raw data into a

format suitable for model training, which can

significantly impact model performance. This process

includes cleaning the data by removing or correcting

inaccuracies, handling missing values, normalizing or

scaling features to ensure consistency across

variables, and selecting or transforming relevant

features to reduce noise.

In Figure 10, we can see that the most used data

preparation steps are feature engineering (89.3%) and

feature selection (71.4%), both of which help identify

the most relevant features for improving model

performance. Data normalization (57.1%) and data

cleaning (53.6%) are also frequently employed, to

ensure that the data is consistent and error-free.

Furthermore, a comparison of two studies using

CNN with MRI data from the ADNI dataset

illustrates the importance of comprehensive data

preparation. Indeed, in (MOHI UD DIN DAR,

2023), thorough data preparation led to an accuracy

of 0.966 for a 5-class classification task, while

(FU’ADAH, 2021), with limited data preparation

achieved a lower accuracy of 0.95 for a 4-class task.

This demonstrates the importance of data cleaning,

normalization, and augmentation in improving

model performance.

4.2.3 Clinical, Non-Clinical vs. Mixed Data

Using mixed data sources allows machine learning

models to capture multiple dimensions of Alzheimer's

Figure 6: Frequency of data types used in the literature.

Figure 7: Percentage of usage for each data preparation step.

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches for Early Alzheimer’s Detection in Patients with Subjective Cognitive Decline: A

Systematic Literature Review

605

disease, ultimately aiding in more accurate diagnoses.

For instance, integrating structural MRI and PET

scans offers anatomical information along with

amyloid deposition patterns, leading to more sensitive

and accurate identification of preclinical AD

(HWANG, 2023). Studies have demonstrated the

superior performance of multimodal data. Integrating

functional and structural neuroimaging data achieved

high diagnostic accuracy across multiple stages of

cognitive impairment (LEI, 2021). In contrast, relying

solely on unimodal data, whether clinical (e.g.,

MRI) or non-clinical (e.g., voice biomarkers), often

fails to capture AD's complex pathology, resulting in

more limited diagnostic accuracy (HWANG, 2023).

4.3 What Are the Practical

Implications of Implementing

Machine Learning Models for

Early Diagnosis of Alzheimer's

Disease in Clinical Settings? (RQ3)

Our review shows that implementing ML models for

early Alzheimer’s detection in clinical settings is

promising but presents practical and ethical

challenges. This section covers three main aspects:

the requirements for clinical integration, ethical

considerations around patient data, and the potential

for cost-effective, non-invasive screening. These

subparts highlight the primary factors impacting the

feasibility, safety, and accessibility of ML in clinical

AD diagnostics, offering insights into what is needed

for successful adoption.

4.3.1 Challenges and Requirements for

Integrating ML Models into Clinical

Workflows

Integrating ML models for AD diagnosis into clinical

settings involves addressing numerous challenges:

a. Population Diversity and Generalizability.

4 studies ((BOHN, 2023), (BAYAT, 2021), (REN Y.

S., 2023) and (HAJJAR, 2023)) suffer from limited

population diversity, focusing predominantly on non-

Hispanic White participants. This narrow

demographic scope can restrict the generalizability of

ML models, as models trained on homogenous data

may not perform well across diverse populations. In

particular, (BOHN, 2023) and (BAYAT, 2021)

emphasize the need for more inclusive datasets to

ensure broader applicability.

b. Sample Size. 12 studies ((KIM, 2023),

(HWANG, 2023), (CHIU, 2022), (REN Y. S., 2023),

(JANG, 2021), (SHIMODA, 2021), (KIM J. L.,

2021), (SCHEIJBELER E. P., 2022), (MURUGAN,

2021), (ANGKOSO, 2022), (OKTAVIAN, 2022) and

(MOHI UD DIN DAR, 2023)) had small sample

sizes. Small datasets limit the robustness of findings

and can lead to biased or unreliable predictions as

they imply overfitting (KIM, 2023).

c. Model and Data Complexity: Some ML

models, particularly deep learning approaches,

require significant computational resources to

perform well. The studies ((SIBILANO, 2023),

(JIANG, 2022), (KIM, 2023), (HWANG, 2023),

(ODUSAMI, 2022) and (ANGKOSO, 2022))

highlight the challenges raised by complex data types

and high dimensional datasets which often require

specialized hardware, making it difficult for settings

with limited resources to implement these models

effectively.

d. Data Quality and Preprocessing: The

quality of data directly impacts model performance.

Inconsistent data quality, especially in custom

datasets, can introduce noise, as seen in the studies

((KIM, 2023), (JANG, 2021), (SHIMODA, 2021),

(KIM J. L., 2021) and (MURUGAN, 2021)).

e. Cross-Validation and External Validation:

For robust performance, machine learning models

must be validated on independent datasets. (CHIU,

2022) and (SCHEIJBELER E. P., 2022) emphasize

the importance of external validation, which helps to

ensure the model's generalizability and reliability.

f. Feature Representation and Selection:

Selecting and representing relevant features is a

complex task, as highlighted by (LIU, 2022), (LEI,

2021), (SHIMODA, 2021) and (KIM J. L., 2021).

Choosing appropriate features directly impacts model

interpretability and performance, as irrelevant or

redundant features can reduce accuracy.

g. Model Interpretability: Complex models,

such as CNN, often lack transparency as

demonstrated in the studies (HWANG, 2023) and

(GAUBERT, 2021), which stress the need for

interpretable models that provide insight into their

decision-making processes, crucial for clinical

adoption.

h. Technological and Methodological

Constraints: 5 studies ((KIM, 2023), (BAYAT,

2021), (GOUW, 2021), (ANGKOSO, 2022) and

(ODUSAMI, 2022)), most of them using EEG,

underline the reliance on specific tools or platforms

limiting the model's applicability and scalability.

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

606

4.3.2 Ethical Concerns in Patient Data Usage

The integration of ML models into clinical practice

raises significant ethical concerns regarding patient

privacy, data security, and informed consent.

Compliance with regulations such as HIPAA in the

U.S. and GDPR in Europe is critical. Several studies

demonstrate rigorous adherence to ethical standards:

(BOHN, 2023) and (HAJJAR, 2023) highlight the

importance of informed consent and strict ethical

oversight to protect patient data. Similarly,

(SIBILANO, 2023) received institutional review

board (IRB) approval, ensuring ethical compliance.

Although datasets like ADNI come with

standardized ethical guidelines and transparency in

data collection, not all studies disclose their adherence

to ethical approval and data governance frameworks.

For instance, (SHAMRAT, 2023) does not mention

regulatory approval despite using ADNI, highlighting

the need for researchers to be transparent about their

specific practices for handling patient data.

4.3.3 Cost-Effective, Non-Invasive,

and Accessible Early Screening

ML models have the potential to revolutionize early

AD diagnosis by leveraging non-invasive and cost-

effective biomarkers. Several studies have explored

innovative approaches that could be integrated into

routine healthcare: (KIM, 2023) achieved high

accuracy using affordable EEG features, providing a

non-invasive screening option. Digital voice

biomarkers (HAJJAR, 2023) and eye-tracking

technologies (JANG, 2021) have demonstrated

efficacy in early AD detection, offering non-invasive

alternatives to traditional neuroimaging or

cerebrospinal fluid analysis.

Additionally, solutions like mobile health

applications and telemedicine platforms can increase

accessibility in low-resource areas. For instance, the

use of GPS driving data to monitor cognitive decline

offers a novel, non-invasive screening method that

could be implemented remotely (BAYAT, 2021).

5 DISCUSSION

5.1 Interpretation of Findings

This systematic literature review demonstrated that

CNN and RF models are the most effective ML

algorithms for diagnosing AD at the preclinical stage.

CNN excels with neuroimaging data such as MRI

(SONG, 2020), while RF models are versatile across

multimodal inputs (BOHN, 2023). Despite their high

accuracy, both face interpretability challenges and

computational demands, highlighting the need for

explainable AI methods and resource-efficient

architectures.

Key Takeaways:

• Model Tuning: Fine-tuning hyperparameters

significantly enhances diagnostic accuracy,

demonstrating that even well-performing models

need thorough optimization.

• Data Types: MRI was the most used and

reliable source, yet multimodal strategies

(integrating neuroimaging, biomarkers, and

cognitive tests) typically yielded higher

accuracy and stronger robustness.

• Data Preparation: Rigorous approaches to

feature engineering, selection, and

augmentation were closely tied to improved

performance, underscoring the importance of

standardized preprocessing protocols.

Challenges:

• Clinical Integration: Barriers include model

interpretability deficits, the variability in data

quality, and the generalizability of findings to

diverse patient populations.

• Ethical and Regulatory Compliance:

Ensuring data privacy and adhering to

frameworks such as GDPR is critical for

clinician and patient trust.

• Accessibility: Cost-effective and non-invasive

methods (e.g., voice biomarkers, EEG, GPS-

driving data) show promise in democratizing

early screening to broader populations,

especially in remote or underserved areas, but

require more robust validation.

5.2 Research Gaps

Despite encouraging progress, several gaps persist in

ML-based early detection of AD:

• Population Diversity: Models used in the

literature are often trained on homogenous

cohorts, limiting generalizability. Larger, more

diverse datasets are needed to ensure equitable

performance across different ethnic and

socioeconomic groups.

• Underexplored Non-Invasive Tools: Voice

biomarkers, EEG, and other low-cost

approaches could enhance accessibility but

remain underexamined relatively compared to

expensive neuroimaging methods.

• Lack of Explainability: Neural networks,

especially CNNs, lack interpretability,

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches for Early Alzheimer’s Detection in Patients with Subjective Cognitive Decline: A

Systematic Literature Review

607

hindering clinical adoption. XAI techniques

are needed to improve transparency and

clinician trust.

• Inconsistent Data Preparation: Varying

preprocessing steps reduce reproducibility,

highlighting a need for standardized

protocols and external validation strategies.

• Ethical and Privacy Concerns: As data

types diversify, stronger frameworks are

needed to protect patient confidentiality.

6 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORKS

This systematic literature review contributes with a

focused analysis of machine learning and deep

learning applications specifically targeting the

preclinical stage of AD, emphasizing the early

detection of cognitive decline marked by SCD.

Unlike broader studies that address AD across

multiple stages, our work narrows in on this critical

early stage, identifying CNN and Random Forest as

top-performing models when combined with

multimodal data and rigorous data preprocessing

methods. By incorporating a computer science

perspective, we provide a detailed examination of ML

and deep learning implementation, particularly in

terms of data preprocessing and model performance,

and offer insights into how these algorithms can be

optimized for early AD diagnosis.

Future research should address several key

limitations identified in this review. First, while

promising, the current ML models lack

explainability, especially with complex models such

as CNN, posing a barrier to clinical adoption.

Integrating XAI techniques into AD diagnostic

models is essential to enhance model transparency

and build clinician trust.

Additionally, this review reveals a need for more

studies leveraging multimodal data that combines

both clinical and non-clinical sources. The integration

of data types such as neuroimaging, voice

biomarkers, and demographic information could

provide a richer, more comprehensive understanding

of early AD indicators and improve model

robustness.

While preprocessing techniques are crucial for

reliable ML outcomes, there is limited

standardization across studies. Future work should

establish consistent preprocessing protocols and

conduct rigorous external validation to ensure model

generalizability and reliability in diverse clinical

settings. By addressing these areas, future research

can advance ML-based AD diagnostics and bring

these technologies closer to practical application,

ultimately benefiting early detection and intervention

efforts in Alzheimer’s Disease.

Moreover, Longitudinal studies following

individuals over extended periods could further

clarify whether early identification of mild cognitive

deficits via ML actually delays the onset or slows the

progression of clinical AD. Such longitudinal data

would also help refine predictive models by

accounting for dynamic changes in cognition and

pathology over time.

Finally, to expedite the adoption of these

frameworks, researchers should collaborate closely

with clinicians, data scientists, ethicists, and

regulatory authorities to ensure patient safety and

meet compliance requirements. Engaging these

stakeholders early in the research cycle can align

technical development with clinical priorities and

facilitate regulatory approvals.

REFERENCES

ANGKOSO, C. V. (2022). Multiplane Convolutional

Neural Network (Mp-CNN) for Alzheimer’s Disease

Classification. In International Journal of Intelligent

Engineering & Systems , vol. 15, no 1.

ARYA, A. D. (2023). A systematic review on machine

learning and deep learning techniques in the effective

diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. In Brain Informatics.

vol. 10, no 1, p. 17.

AVRAAM, B. N. (2023). Local Interpretability of Random

Forests for Multi-Target Regression. arXiv preprint

arXiv:2303.16506.

BAYAT, S. B. (2021). GPS driving: a digital biomarker for

preclinical Alzheimer disease. In Alzheimer's Research

& Therapy, vol. 13, no 1, p. 115.

BLENNOW, K. e. (2018). Biomarkers for Alzheimer's

disease: current status and prospects for the future. In

Journal of internal medicine, vol. 284, no 6, p. 643-663.

BOHN, L. D. (2023). Machine learning analyses identify

multi-modal frailty factors that selectively discriminate

four cohorts in the Alzheimer’s disease spectrum: a

COMPASS-ND study. In BMC geriatrics, vol. 23, no

1, p. 837.

CHEN, S. e. (2011). A novel support vector classifier for

longitudinal high‐dimensional data and its application

to neuroimaging data. In Statistical Analysis and Data

Mining: The ASA Data Science Journal, vol. 4, no 6, p.

604-611.

CHIU, S.-I. F.-Y.-H. (2022). Machine learning-based

classification of subjective cognitive decline, mild

cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s dementia using

neuroimage and plasma biomarkers. In ACS Chemical

Neuroscience, vol. 13, no 23, p. 3263-3270.

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

608

DARA, O. A.-G. (2023). Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis

Using Machine Learning: A Survey. Applied Sciences.

vol. 13, no 14, p. 8298.

EBRAHIMI, A. L. (2021). Convolutional neural networks

for Alzheimer’s disease detection on MRI images. In

Journal of Medical Imaging, p. 024503-024503 vol. 8

no 2.

FU’ADAH, Y. N. (2021). Automated classification of

Alzheimer’s disease based on MRI image processing

using convolutional neural network (CNN) with

AlexNet architecture. In Journal of physics: conference

series. IOP Publishing, p. 012020.

GAUBERT, S. H. (2021). A machine learning approach to

screen for preclinical Alzheimer's disease. In

Neurobiology of Aging, vol. 105, p. 205-216.

GOUW, A. A. (2021). Routine magnetoencephalography in

memory clinic patients: A machine learning approach.

In Alzheimer's & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment &

Disease Monitoring, vol. 13, no 1, p. e12227.

HAJJAR, I. O. (2023). Development of digital voice

biomarkers and associations with cognition,

cerebrospinal biomarkers, and neural representation in

early Alzheimer's disease. In Alzheimer's & Dementia:

Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring,, vol. 15,

no 1, p. e12393.

HORENKO, I. V. (2023). On cheap entropy-sparsified

regression learning. In Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences, vol. 120, no 1, p. e2214972120.

HUANG, G. L. (2023). Multimodal learning of clinically

accessible tests to aid diagnosis of neurodegenerative

disorders: a scoping review. In Health Information

Science and Systems, vol. 11, no 1, p. 32.

HWANG, U. K.-W. (2023). Real-world prediction of

preclinical Alzheimer’s disease with a deep generative

model. In Artificial Intelligence in Medicine, vol. 144,

p. 102654.

JANG, H. S. (2021). Classification of Alzheimer’s disease

leveraging multi-task machine learning analysis of

speech and eye-movement data. In Frontiers in Human

Neuroscience, vol. 15, p. 716670.

JESSEN, F. A. (2014). A conceptual framework for

research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical

Alzheimer's disease. In Alzheimer's & dementia, vol.

10, no 6, p. 844-852.

JIANG, Z. S. (2022). Automated analysis of facial emotions

in subjects with cognitive impairment. In Plos one, vol.

17, no 1, p. e0262527.

KIM, J. L. (2021). Development of random forest algorithm

based prediction model of Alzheimer’s disease using

neurodegeneration pattern. In Psychiatry Investigation

, vol. 18, no 1, p. 69.

KIM, N. H. (2023). PET-validated EEG-machine learning

algorithm predicts brain amyloid pathology in pre-

dementia Alzheimer’s disease. In Scientific Reports,

vol. 13, no 1, p. 10299.

KINGSMORE, K. M. (2021). An introduction to machine

learning and analysis of its use in rheumatic diseases. In

Nature Reviews Rheumatology, vol. 17, no 12, p. 710-

730.

KITCHENHAM, B. (2004). Procedures for Performing

Systematic Reviews.

KITCHENHAM, B. (2007). Guidelines for performing

Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering

(Kitchenham).

Land, W. A. (2002). Application of support vector

machines to breast cancer screening using mammogram

and history data. In Medical Imaging 2002: Image

Processing, SPIE, 2002. p. 636-642.

LEI, B. C. (2021). Auto-weighted centralised multi-task

learning via integrating functional and structural

connectivity for subjective cognitive decline diagnosis.

In Medical Image Analysis, vol. 74, p. 102248.

LIU, Y. Y. (2022). Assessing clinical progression from

subjective cognitive decline to mild cognitive

impairment with incomplete multi-modal neuroimages.

In Medical image analysis, vol. 75, p. 102266.

LOGAN, R. W. (2021). Deep Convolutional Neural

Networks With Ensemble Learning and Generative

Adversarial Networks for Alzheimer’s Disease Image

Data Classification, In Frontiers in aging neuroscience,

vol. 13, p. 720226.

MANDHALA, V. S. (2014). Scene classification using

support vector machines. In IEEE International

Conference on Advanced Communications, Control

and Computing Technologies, 1807-1810.

MATTIA, G. V. (2021). Neurodegenerative Traits Detected

via 3D CNNs Trained with Simulated Brain MRI:

Prediction Supported by Visualization of Discriminant

Voxels. In IEEE International Conference on

Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM) (pp. 1437-

1442).

MENEZES, F. L. (2017). Data classification with binary

response through the Boosting algorithm and logistic

regression. In Expert Syst. Appl., 69, 62-73.

MOHI UD DIN DAR, G. B. (2023). A novel framework for

classification of different Alzheimer’s disease stages

using CNN model. In Electronics, vol. 12, no 2, p. 469.

MURUGAN, S. V. (2021). DEMNET: A deep learning

model for early diagnosis of Alzheimer diseases and

dementia from MR images. In Ieee Access, vol. 9, p.

90319-90329.

ODUSAMI, M. M. (2022). An intelligent system for early

recognition of Alzheimer’s disease using

neuroimaging. In Sensors, vol. 22, no 3, p. 740.

OKTAVIAN, M. W. (2022). Classification of Alzheimer's

disease using the Convolutional Neural Network

(CNN) with transfer learning and weighted loss. arXiv

preprint arXiv:2207.01584.

PARSIFAL. (n.d.). Parsifal. https://parsif.al/about/

RABIN, L. A. (2017). Subjective cognitive decline in

preclinical Alzheimer's disease. In Annual review of

clinical psychology, vol. 13, p. 369-396.

REN, Y. S. (2023). Improving clinical efficiency in

screening for cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's.

In Alzheimer's & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment &

Disease Monitoring, vol. 15, no 4, p. e12494.

REN, Y. X. (2022). Label distribution for multimodal

machine learning. In Frontiers of Computer Science,

vol. 16, p. 1-11.

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches for Early Alzheimer’s Detection in Patients with Subjective Cognitive Decline: A

Systematic Literature Review

609

SÁEZ, C. R. (2021). Potential limitations in COVID-19

machine learning due to data source variability: A case

study in the nCov2019 dataset. In Journal of the

American Medical Informatics Association, vol. 28, no

2, p. 360-364.

SARICA, A. C. (2017). Random Forest Algorithm for the

Classification of Neuroimaging Data in Alzheimer's

Disease: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Aging

Neuroscience, vol. 9, p. 329.

SCHEIJBELER, E. P. (2022). Network-level permutation

entropy of resting-state MEG recordings: A novel

biomarker for early-stage Alzheimer’s disease? In

Network Neuroscience, vol. 6 (no 2), p. 382-400.

SCHEIJBELER, E. P. (2022). Generating diagnostic

profiles of cognitive decline and dementia using

magnetoencephalography. In Neurobiology of aging,

vol. 111, p. 82-94.

SHAMRAT, F. J. (2023). AlzheimerNet: An effective deep

learning based proposition for alzheimer’s disease

stages classification from functional brain changes in

magnetic resonance images. In IEEE Access, vol. 11, p.

16376-16395.

SHEN, Y. Y. (2018). Cognitive decline, dementia,

Alzheimer’s disease and presbycusis: examination of

the possible molecular mechanism. In Frontiers in

neuroscience, vol. 12, p. 327937.

SHIMODA, A. L. (2021). Dementia risks identified by

vocal features via telephone conversations: A novel

machine learning prediction model. In PloS one, vol.

16, no 7, p. e0253988.

SIBILANO, E. B. (2023). An attention-based deep learning

approach for the classification of subjective cognitive

decline and mild cognitive impairment using resting-

state EEG. In Journal of Neural Engineering, vol. 20,

no 1, p. 016048.

SONG, T.-A. C. (2020). Super-resolution PET imaging

using convolutional neural networks. In IEEE

transactions on computational imaging, vol. 6, p. 518-

528.

TER HUURNE, D. R. (2023). The Accuracy of Speech and

Linguistic Analysis in Early Diagnostics of

Neurocognitive Disorders in a Memory Clinic Setting.

In Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, vol. 38, no 5,

p. 667-676.

ZOTERO. (n.d.). Zotero. https://www.zotero.org/.

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

610