Modulating Cerebral Rhythms in Parkinson's Disease: Insights on

the Role of Auditory Stimulation

Pablo García-Peña

1a

, Juan M. López

2b

, Milagros Ramos

1,3,4 c

, Daniel González-Nieto

1,3,4 d

and Guillermo de Arcas

2,5,6 e

1

Center for Biomedical Technology (CTB), Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain

2

Instrumentation and Applied Acoustics Research Group (I2A2), Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain

3

Departamento de Tecnología Fotónica y Bioingeniería, ETSI Telecomunicaciones, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid,

Madrid, Spain

4

Biomedical Research Networking Center in Bioengineering Biomaterials and Nanomedicine (CIBER-BBN), Madrid, Spain

5

Departamento de Ingeniería Mecánica, ETSI Industriales, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain

6

Laboratorio de Neuroacústica, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain

Keywords: 40 Hz, Gamma Entrainment, C57BL/6, Electroencephalography, Slowing EEG.

Abstract: Parkinson's disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by a slowing of brain rhythms, leading

to cognitive and motor deficits. Auditory stimulation (AS) has proven to have great potential as a non-invasive

approach to modulate brain activity. Nevertheless, despite promising clinical and preclinical findings, optimal

AS parameters for its use in PD remain unclear. To investigate the potential therapeutic effects of AS in PD,

we aimed to establish an optimal preclinical model and stimulation protocol. Two mouse strains were

compared, CD1 and C57BL/6, and assessed their auditory sensitivity. 3-months C57BL/6 mice was selected

as the most suitable model for auditory studies. Two literature-based AS protocols were applied, a 10 kHz

carrier tone modulated with 40 Hz pulses and a 40 Hz amplitude-modulated tone. Our results demonstrate

that comparing pre- and post-stimulation periods, the 10 kHz/40 Hz protocol consistently induced a reduction

in delta power and an increase in gamma relative power, with persistent effects of the latter 24 hours post-

stimulation. These findings suggest that this specific AS protocol holds promise for targeting abnormal brain

rhythms associated with PD and may have potential therapeutic implications. Further research is needed to

explore the underlying mechanisms and optimize AS parameters for clinical translation.

1 INTRODUCTION

Parkinson's disease (PD), a neurodegenerative

disorder characterized by motor impairments

(tremors, rigidity and akinesia), hyposmia and

cognitive decline with sleep disorders, is a significant

global health burden. PD has been identified as the

fastest growing neurological condition affecting 11.8

million people globally in 2021, a 273.9% increase

since 1990 (Steinmetz et al., 2024). The pathological

hallmark of PD is the loss of dopaminergic neurons

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4928-0213

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7847-8707

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5798-9508

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2972-729X

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1699-7389

in the substantia nigra, leading to dysregulation of

neuronal circuits in the basal ganglia and impairment

of nigrostriatal pathway. This disruption results in

abnormal brain activity, including altered neuronal

oscillations.

Electroencephalography (EEG) studies in PD

patients have revealed a characteristic pattern of

abnormal brain waves, characterized by an early

increase in delta band activity (Caviness et al., 2015;

Chu et al., 2021). Additionally, there is a reduction in

gamma band activity (Ahveninen et al., 2000), which

752

García-Peña, P., López, J. M., Ramos, M., González-Nieto, D. and de Arcas, G.

Modulating Cerebral Rhythms in Parkinson’s Disease: Insights on the Role of Auditory Stimulation.

DOI: 10.5220/0013247800003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 1, pages 752-762

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

plays a crucial role in information processing and

cognitive functions. Taken together, these findings

suggest that a characteristic hallmark of PD is a

slowing cerebral rhythms, associated with cognitive

dysfunction (Bosboom et al., 2006; Soikkeli et al.,

1991) an impairment that highly correlates with

motor decline (Miladinović et al., 2021).

Efforts to develop novel therapeutic strategies for

PD have focused on restoring normal neuronal

activity and enhancing brain plasticity. While deep

brain stimulation (DBS) has shown some success, it

carries risks and may not be suitable for all patients

due to surgery risks (Zhang et al., 2017). Non-

invasive brain stimulation techniques, such as

transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and

transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), offer

alternative approaches to modulating brain activity,

however, further research optimizing stimulation

parameters is needed to enhance their clinical utility

(Benninger et al., 2010; Goodwill et al., 2017). There

are not pharmacological or non-pharmacological

therapies able to slow the progression of PD.

Auditory stimulation (AS) in the audible range

has emerged as a promising and non-invasive

approach for modulating neuronal activity. This

method involves using sound waves to modulate

brain activity by a mechanism called oscillatory

entrainment. This process occurs when neural

intrinsic oscillations synchronize with external

rhythmic stimulus (Henao et al., 2020; Ross & Lopez,

2020). This synchronization enhances neural activity

at the stimulus frequency by increasing signal

amplitude and/or by phase-locking, where phases of

neural oscillations align with specific phases of the

stimulus (Henao et al., 2020) By these

synchronizations, rhythmic stimuli can modulate

brain regions beyond sensory areas, reaching

supramodal regions and impacting higher-level

cognitive functions (Albouy et al., 2022) and

influence neuroprotection and neural plasticity

(Adaikkan & Tsai, 2020; Fujiki et al., 2020).

Specifically, neuronal entrainment has been

observed at different frequencies, but especially in the

beta-gamma range (13–44 Hz) (Will & Berg, 2007).

In animal models, direct microelectrode recordings

into the primary auditory cortex demonstrated an

entrainment of local field potential in response to 40-

click train stimuli (Li et al., 2018; Nakao &

Nakazawa, 2014) Several studies in mice model have

demonstrated AS potential to induce gamma

entrainment, as therapy approach in various

neurological diseases, including dementia (Chan et

al., 2022) ischemia (Zheng et al., 2020) and

Alzheimer's disease (AD) (Liu et al., 2022), were a 40

Hz audio-visual stimulation induced gamma

oscillation and reduced amyloid plaque promoting

glymphatic clearance (Iaccarino et al., 2016;

Martorell et al., 2019; Murdock et al., 2024). These

findings suggest that neuronal entrainment through

visual or auditory stimulation could not only mitigate

cognitive decline but also emerge as a potential

treatment for neurodegenerative diseases

characterized by the accumulation of pathogenic

proteins.

In PD, rhythmic auditory stimulation (RAS) is

often used in rehabilitation to engage alternative

motor networks or enhances basal ganglia function,

potentially improving gait, tremors and quality of life

(Benoit et al., 2014; Bukowska et al., 2015; Ye et al.,

2022). Our research group has previously conducted

clinical studies investigating the effects of Binaural

Beat Stimulation (BBs) in cognitive function and

brain activity in PD patients. The results suggest that

BBs can initially reduce theta power in the brain,

similar effect to the normalization seen with levodopa

treatment, which may lead to improvements in motor

function and cognition. However, this effect appears

to diminish over time due to habituation. While some

patients showed sustained benefits, others exhibited

variable responses, highlighting the need for further

research to optimize the timing and duration of BBs

to maximize therapeutic effects (Gálvez et al., 2018;

González et al., 2023).

Despite these promising findings, the optimal

parameters for AS in PD remain elusive. A lack of

standardized AS protocols hinders cross-study

comparisons and clinical translation (Ingendoh et al.,

2023). Moreover, the potential therapeutic effects of

AS observed in AD are uncertain in the context of PD.

To fill this knowledge gap, a preclinical model of AS

in PD is essential to systematically investigate the

effects of different stimulation parameters, including

frequency, intensity, and modulation, and to identify

the most effective protocols for modulating neural

activity and improving motor and cognitive function.

To advance our research on this topic, this study

focused on examining the influence of AS on cerebral

rhythms in the unmodified mouse brain. The goal was

to determine whether an AS signal with defined

parameters (see methods) could optimally induce

persistent gamma entrainment and potentially

counteract EEG slowing, which could have

preclinical and clinical implications for the

application of AS paradigms in PD.

Modulating Cerebral Rhythms in Parkinson’s Disease: Insights on the Role of Auditory Stimulation

753

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Animals

Adult male mice CD1 (outbred strain; Charles River

Laboratories; RRID:MGI:5649524) and C57BL/6

Ola (inbred strain; Jackson Laboratory;

RRID:MGI:2162680), both aged 3 and 6 months

were used in these studies. All procedures were

conducted in compliance with national ethical and

legal standards and were authorized by the Ethical

Committee of the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid,

and the regional government of Madrid (authorization

code PROEX 108.0/20). The reporting of this

manuscript was conducted according to the Animal

Research Reporting In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE)

guidelines.

To minimize potential damage to the head-

mounted electrode caps, the mice were housed

individually in polycarbonate cages (267 × 208 mm).

The animals were provided with ad libitum access to

food and water, with cellulose bedding and cotton

enrichment for environmental stimulation. The

animals were maintained and monitored by a

veterinarian and qualified personnel at the Centre for

Biomedical Technology (Pozuelo de Alarcón, Spain).

The housing conditions were strictly controlled, with

a temperature of 21 ± 2°C, a relative humidity of 40-

60%, and a 12-hour light/dark cycle. All mice were

deemed healthy based on serological and PCR

testing, adhering to Federation of Laboratory Animal

Science Associations (FELASA) recommendations.

Daily routines were conducted between 7 AM and

4 PM, with consistent and qualified personnel

assigned to each experimental procedure. To

characterize auditory capacity, a preliminary test was

conducted with four groups of four mice each based

on both mouse strains and two ages (3 and 6 months)

to select the strain with optimal hearing for

subsequent AS protocols. To investigate the effect of

two AS protocols in EEG, two groups of five mice

each for both protocols were selected from the best

hearing condition.

2.2 Electrodes Implantation

Mice underwent surgery for chronic implantation of

electrodes in parietal-temporal areas to cortical

auditory evoked potentials (CAEPs). We also

implanted intracranial electrodes for

electroencephalography (iEEG) recordings. In both

procedures, the animals were anesthetized with

ketamine (Imalgene, 80 mg/kg, i.p.) and xylazine

(Rompun, 10 mg/kg, i.p.), and afterward by

iodopovidone (Betadine, Avrio Health). Alcohol

wipes were applied to the skin. Anaesthetic depth was

monitored every 5 minutes by assessing pedal

withdrawal reflex. Prior to surgery, mice were treated

with an ophthalmic solution to prevent eye drying.

The rectal temperature was maintained during

surgical procedures by a heating pad (RTC-1 Thermo

Controller Surgery Table, Cibertec) at a body

temperature of 37 ± 0.5 °C.

Craniotomies were performed at the electrode

locations specified below using a dental drill. Four

stainless-steel electrodes (P1 Technologies) were

implanted for CAEPs recordings on the right (AP -2.5

mm; L -4.3 mm; DV 0.0 mm, anatomic locations

from bregma) and left auditory cortices (AP -2.5 mm;

L +4.3 mm; DV 0.0 mm). Two additional electrodes

were implanted as reference (AP 1.5 mm; L +2.0 mm;

DV 0.0 mm from bregma) and ground (AP 1.5 mm;

L -2.0 mm; DV 0.0 mm). For intracranial EEG

(iEEG) recordings, the electrodes were implanted in

the right hemisphere in frontal (AP +1.0 mm; L +10

mm; DV 0.0 mm) and parietal cortex areas (AP -3.5

mm; L +1.0 mm; DV 0.0 mm), following the same

anatomic locations reported in a previous study (Lee

et al., 2018). Reference (AP -5.3 mm; L 0.0 mm; DV

0.0 mm from bregma) and ground (AP -2.0 mm; L

+1.5 mm; DV 0.0 mm) electrodes were also

implanted (Figure 1A).

Figure 1: Experimental Setup. (A) Electrode placement for

frontal and parietal intracranial EEG (iEEG) recording. (B)

Experimental setup for simultaneous auditory stimulation

and iEEG recording.

After the electrode’s implantation, the skull was

dried, the coated portions of the wires were secured

with gel glue (Henkel, Loctite 454) and covered with

dental cement (DuraLay, Inlay Pattern Resin Powder

and Liquid). A header (P1 Technologies) was

connected to the wires and angled upwards.

For pain management, buprenorphine (Buprex,

0.05 mg/kg) was administered subcutaneously before

and 8 hr after surgery. The animals were allowed to

recover for 1 hr in a warm environment before

returning to the standard housing environment.

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

754

2.3 CAEPs Recordings

Mice hearing thresholds and auditory discrimination

were study by CAEPs recordings following Mei et al.

(2021) and Martorell et al. (2019) methodologies and

our previous knowledge on evoked potentials

recordings (Barios et al., 2016; Fernández-García et

al., 2016, 2018; Fernández-Serra et al., 2022)

Animals recovered for at least 1 week after electrodes

implantation. For evoked potentials recordings, mice

were first anaesthetized with ketamine and xylazine

and treated with an ophthalmic solution to prevent

eye drying. During auditory stimulation, anaesthetic

depth and body temperature were maintained. Two

speakers (Logitech Multimedia Speakers Z200) were

place facing each other and 25 cm away from left and

right mice ears. Stimulus consisted of a series of 50

ms tones of 0.5 and 1 kHz with a stimulating rate of 1

Hz, from a level of sound pressure level (SLP; SC310

sound level meter, CESVA) of 100 dB decreasing in

10 dB steps until no response was detected (hearing

threshold) or sound intensity level reached the

ambient noise level (~54.3 dB). The recording time

window was 500 ms, starting 50 ms before the

beginning of the stimulation, with 4,096 Hz sampling

rate. The signal was bandpass filtered at 0.2–2000 Hz

and averaged 300 times. Signals were recorded in an

isolated chamber by using a portable

electromyography (EMG)-evoked potentials (EP)

device (Micromed, Italy) and SystemPLUS Evolution

software (v.1.4; Micromed). Peak amplitudes of the

main potential wave (N1 component) were measured

in relation to the first 50 s as baseline.

2.4 iEEG Recordings and Analysis

For recovery and habituation, the mice were moved

to the recording room, 1 week prior to the start of the

recording sessions. iEEG signals were acquired in

mice with freedom of movement in a 30 × 30 × 30 cm

cage during 3-hr sessions (Figure 1B), following

previous methodologies of our group (García-Peña et

al., 2023; Herrero et al., 2021)The header was

attached to a flexible cable (P1 Technologies) and

connected to single-channel AC amplifiers (Grass,

78D). The power line frequency was removed using

a 50 Hz notch filter. The cortex signals were

amplified by 8,000x, bandpass filtered (CyberAmp,

Axon Instruments, 380) at 0.3–100 Hz. Signals were

then digitally converted (National Instruments, BNC-

2090A) at a sampling frequency of 500 Hz and

recorded using the LabVIEW Biomedical Toolkit

software (v.2012; National Instruments;

RRID:SCR_014325).

For spectral analysis, the power in the range of 0–

100 Hz with a 1024-bin size was calculated using a

customized code from MATLAB software (version

2022b). EEG frequency bands were classified into

delta (δ; 0.5–4 Hz), theta (θ; 4–8 Hz), alpha (α; 8–12

Hz), beta (β; 14–30 Hz) and gamma (γ; 30–100 Hz).

Before (PRE) and after (POST) relative band power

change was calculated subtracting POST to PRE

relative power for each band power studied.

Spectrograms representing powers at frequencies

up to 100 Hz were obtained using a Hamming

window with a block size of 512 and 2048 for the 0.5-

4 Hz and the 30-100 Hz spectrograms, respectively,

calculated using Spike2 (v. 6.18, Cambridge

Electronic Design; RRID:SCR_000903).

2.5 Auditory Stimulation Experimental

Designs

All AS protocols were generated by custom-built

program under LabVIEW Virtual Instrument and

delivered via two opposite speakers (Logitech

Multimedia Speakers Z200) placed 20 cm above the

ground of the cage (Figure 1B).

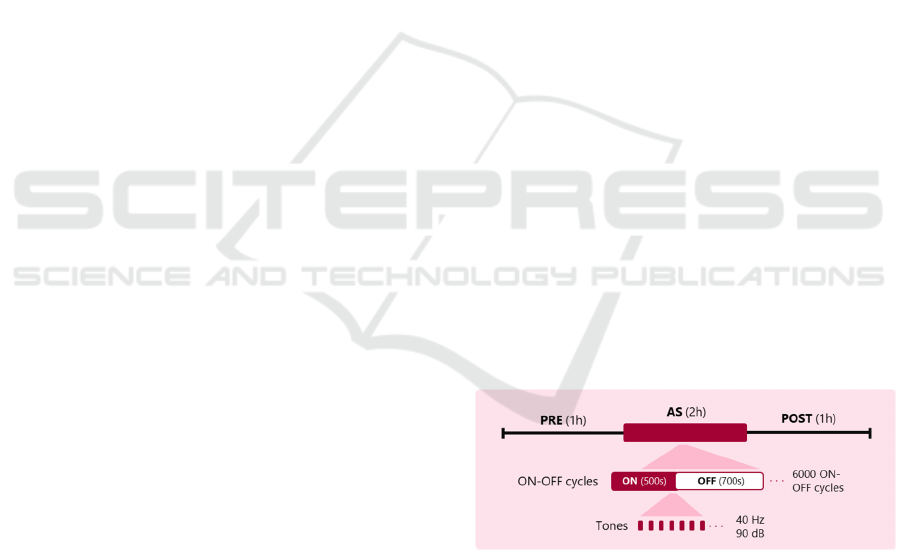

2.5.1 AS-Protocol 1

The proposed protocol adapts Lee et al. (2018)

auditory stimulation protocol. Briefly, mice

underwent a 1-day duration auditory stimulation of 1-

hr session accompanied by 1-hr iEEG recordings

immediately before (PRE) and after (POST)

stimulation. One day after starting the protocol (basal;

B; D0) and in non-stimulation days iEEG recordings

were performed but no stimulation (Figure 2).

Figure 2: AS-protocol 1 adapted from Lee et al. (2018). 2-

h auditory stimulation (AS) of 500-s ON (40 Hz tones) and

700-s OFF periods was preceded and followed by 1 h of

iEEG recordings, PRE and POST respectively.

Mice were exposed to tones of 40 Hz. 20 pulses

of 10 ms delivered at a SPL of 90 dB were played.

Animals were presented with 1.2-s cycles alternating

500 ms of audio stimulation (ON period) interleaved

with 700 ms of no tones (OFF period). Stimuli were

presented in this manner for 2-hr sessions for 7200

ON-OFF cycles according to protocol (Table 1).

Modulating Cerebral Rhythms in Parkinson’s Disease: Insights on the Role of Auditory Stimulation

755

Table 1: Comparison of AS protocols.

As-protocol 1 AS-protocol 2

Tones 40 Hz 10 kHz

Modulation None 40 Hz

Cycles

500 ms ON

700 ms OFF

10 s ON

10 s OFF

SLP 90 dB 90 dB

Sessions 2 h 1 h

Adapted

from

(Lee et al.,

2018)

Martorell et al.

(2019)

and Lee et al.

(2018)

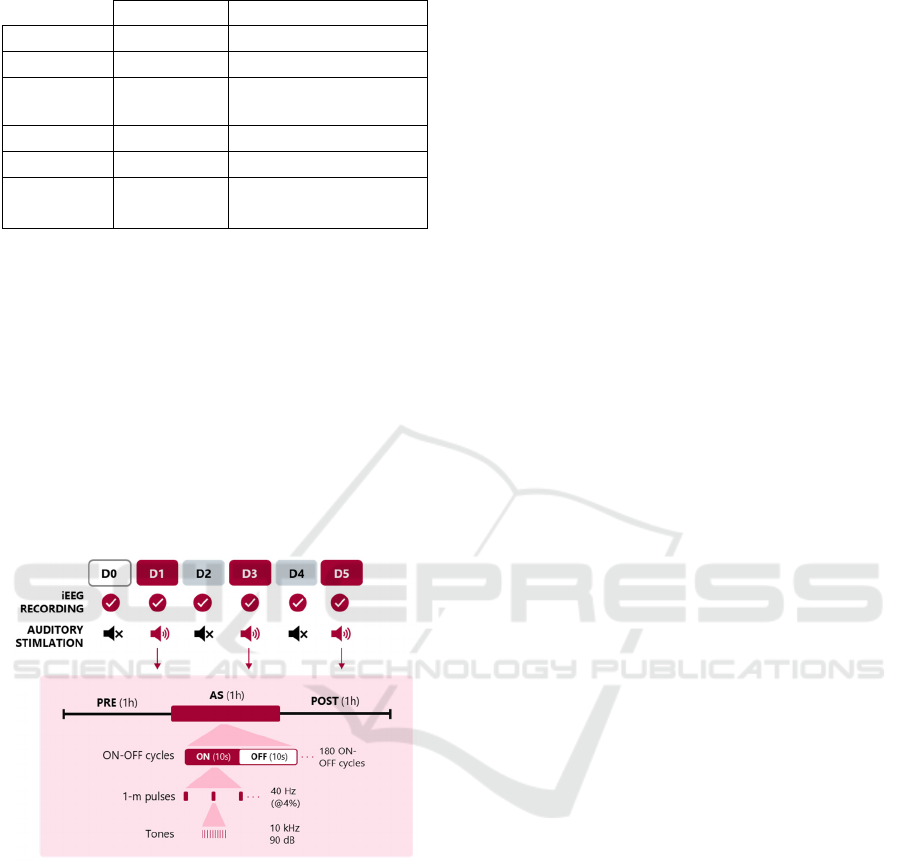

2.5.2 AS-Protocol 2

The proposed protocol adapts Martorell et al. (2019)

and Lee et al. (2018) auditory stimulation protocols.

Briefly, mice underwent a 5-day duration with

alternating days auditory stimulation of 1-hr session

(AS; D1, D3 and D5) interleaved with non-

stimulating days (resting period; RP; D2 and D4)

accompanied by 1-hr iEEG recordings immediately

before (PRE) and after (POST) stimulation. One day

after starting the protocol (basal; B; D0) and in non-

stimulation days iEEG recordings were performed

but no stimulation (Figure 3).

Figure 3: AS-protocol 2 adapted from Martorell et al.

(2019) and Lee et al. (2018). 1-h auditory stimulation (AS)

of 10-s ON (40 Hz pulses modulating 10 kHz tones) and

10-s OFF periods was preceded and followed by 1 h of

iEEG recordings, PRE and POST respectively, in

alternating days (D1, D3 and D5). Basal day (D0) and

resting days (D2 and D4), iEEG recording was performed

but no stimulation was not.

Mice were exposed to 1-ms pulses of 10 kHz

tones presented at 40 Hz. Pulses were delivered at 25

ms intervals (40 Hz with a 4% duty cycle) and at SPL

of 90 dB. Animals were subjected to 20-s cycles

alternating between 10-s periods of audio stimulation

(ON periods) interleaved with 10-s periods without

stimulation (OFF periods). These stimuli were

presented during 1-hr sessions, each consisting of 180

ON-OFF cycles, administered on AS days in

accordance with the protocol (Table 1).

2.6 Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using

SigmaPlot v.12.0 (Systat, Germany). Unless

otherwise indicated, all statistical data are presented

as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Outliers

were detected and removed using the z-score method

with a threshold of 2.0. Removal of outliers had no

significant impact on the results of the analysis.

Shapiro-Wilk normality test and the test for equality

of variance were performed. For normally distributed

data, an analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA)

followed by Bonferroni multiple comparison post-

hoc test were applied to determine significant

differences in the POST–PRE relative band power.

For not-normally distributed data, Kruskal-Wallis H

test followed by Dunn multiple comparison post-hoc

test were applied. Statistical significance was defined

as a p-value less than .05 (p < .05). Statistical values

were expressed as: *, if .05 > p > .005; **, if .005 > p

> .001; and ***, if p > .001.

3 RESULTS

To establish optimal experimental conditions for

investigating auditory-evoked neuronal oscillations,

we first conducted a comparative analysis of the

auditory capacity in CD1 and C57BL/6 mice, to select

the more suitable mouse strain where to test the effect

of auditory stimulation on spontaneous EEG. The

choice of CD1 and C57BL/6 mice strains was based

on their distinct genetic profiles, allowing for a

comprehensive evaluation of AS efficacy across

diverse genetic backgrounds, thereby increasing the

generalizability of the findings to a broader

population.

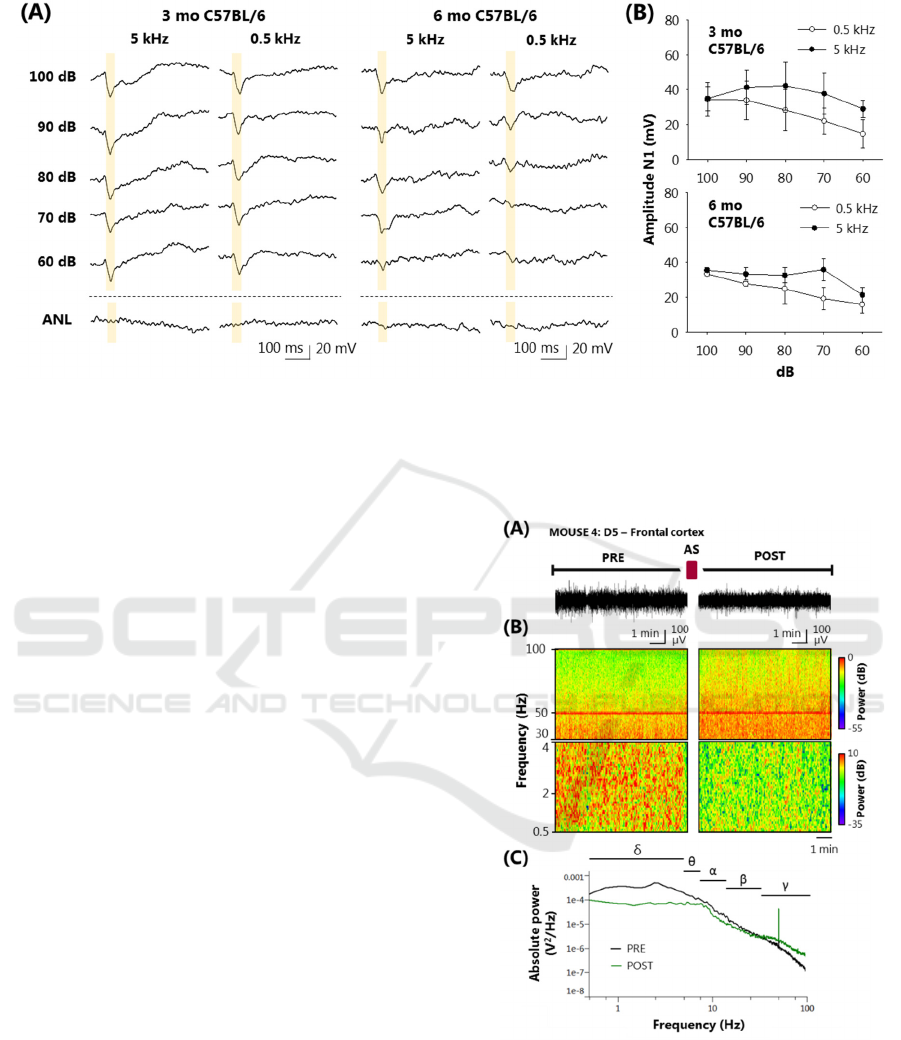

CAEPs recordings revealed a pronounced age-

dependent decline in hearing sensitivity in CD1 mice,

with complete auditory loss observed at 3 and 6

months of age at 0.5 and 5 kHz (0 of 8 CD1 mice of

both ages periods responded at the maximum of 100

dB; data not shown). In contrast, C57BL/6 mice aged

3 months maintained auditory function for 5 kHz

(41.57 ± 10.005 mV of N1 peak at 90 dB in the right

hemisphere) and 0.5 kHz (33.98 ± 9.067 mV) (Figure

4). Also, C57BL/6 exhibited a notable reduction in

hearing sensitivity at 6 months with no detectable

evoked responses in 2 of 4 mice studied at ~60 dB for

5 kHz and at ~70 dB for 0.5 kHz stimulation in the

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

756

Figure 4: C57BL/6 mice auditory capacity evaluation by CAEPs. (A) CAEPs recordings of 3 (3 mo) and 6 (6 mo) months old

C57BL/6 mice at 5 and 0.5 kHz stimuli from 100 to 60 dB SPL dB. ANL means ambient noise level. (B) N1-peak amplitude

from first 50-ms baseline of 3 (upper graph) and 6 months old (lower graph) C57BL/6 mice at 5 and 0.5 kHz. Recordings

without an identifiable N1-peak were removed from the mean. Data is shown as means ± SEM analysed from four recordings

from each condition. No statistical analysis was performed.

right hemisphere. Among 6-months C57BL/6

mice with a detected N1-wave, a reduction auditory

function at 5 kHz (33.52 ± 3.55 mV of N1 peak at 90

dB in the right hemisphere) and 0.5 kHz (27.70 ± 1.21

mV) was observed compared with 3-months

C57BL/6 (Figure 4). N1 amplitude showed no

significant differences between the left and right

hemispheres in CD-1 and C57BL/6 mice with all the

parameters studied. These findings indicate how

crucial is to select an adequate mouse strain in

auditory research and suggest that C57BL/6 mice at 3

months might represent an appropriate model for

studying auditory-driven neural activity.

To investigate the impact of 40 Hz auditory

stimulation on iEEG activity, studies in 3-month-old

C57BL/6 mice were conducted following AS-

protocol 1 and 2 detailed in 2.4 subsection of

Materials and Methods, that include frequencies

higher than 0.5 kHz and SPL above 60 dB.

AS-protocol 1 adapted from Lee et al. (2018) with

40 Hz auditory pulses without high-frequency carrier

tone, showed no effects of auditory stimulation in

EEG power (data not shown). No longitudinal study

was performed.

AS-protocol 2 adapted from Martorell et al.

(2019) and Lee et al. (2018) with 10 kHz carrier tone

modulated by 40 Hz auditory pulses, showed EEG

changes produced by AS (Figure 5). iEEG recordings

were stable during 1-hr recording and total power

showed no statistical differences between days (data

not shown). Baseline-day (B) recordings revealed no

significant differences in POST–PRE relative

Figure 5: Spectral analysis of pre- (PRE) and post- (POST)

stimulation periods at day 5 from AS-protocol 2. (A)

Representative 10-min intracranial electroencephalography

(iEEG) recordings of D5 PRE and POST periods. (B)

Spectrograms (0.5–4 Hz, delta, upper panel; 30–100 Hz,

gamma, lower panel) obtained from the two same PRE and

POST regions showed in panel A. (C) Absolute power

iEEG of same PRE and POST regions showed in panel A

showing delta (δ) and theta (θ), and alpha (α), beta (β), and

gamma (γ) bands.

Modulating Cerebral Rhythms in Parkinson’s Disease: Insights on the Role of Auditory Stimulation

757

Figure 6: Relative power bands difference between pre- (PRE) or post-stimulation (POST) during basal day (B), auditory

stimulation days (D1, D3 and D5) and resting period days (D2 and D4) obtained from iEEG recordings of five mice at AS-

protocol 2. Data is shown as means ± SEM analyzed from five mice. No statistical test were performed.

potentials and in all frequency bands studied (Figure

6). However, during AS, frontal cortex showed a

consistent increase in gamma POST–PRE relative

power (+1.31 ± 0.38 %) accompanied by a marked

reduction in delta POST–PRE relative power (-2.54 ±

0.25 %), compared to their basal. The parietal cortex

showed the same observations in delta and gamma

POST–PRE relative powers (data not shown).

A longitudinal analysis of the data revealed that

delta relative power decreased during the post-

stimulation period compared to the pre-stimulation

period (Figure 7). However, subsequent resting days

(D2 and D4) showed a recovery of delta power to

baseline levels. Gamma relative power, on the other

hand, was increased during the post-stimulation

period and this effect persisted for at least one day

post-stimulation, as indicated in resting days (D2 and

D4). However, the effect of gamma power

enhancement appeared to dissipate by the second

resting day, as the PRE period of the subsequent

stimulation day (D3-PRE and D5-PRE) returned to

baseline levels. There were not statistically

significant differences in one-way ANOVA analysis.

4 DISCUSSION

The present study aims to establish a preclinical

model of AS to investigate its potential to modulate

aberrant neural oscillations in PD. Despite promising

findings in human studies demonstrating the capacity

of AS to normalize EEG power and enhance

functional connectivity (Gálvez et al., 2018;

González et al., 2023) and promising mice studies in

AD (Lee et al., 2018; Martorell et al., 2019; Murdock

et al., 2024), the optimal parameters for AS in PD

remain elusive. A standardized preclinical model is

crucial to systematically explore the effects of various

stimulation parameters to ensure accurate,

reproducible, and translatable results into effective

clinical interventions. Even though PD mice models

do not fully replicate all features of human pathology,

PD mice models are useful for studying specific

aspects of the disease, performing moderate invasive

procedures or chronic recordings and stimulations

that are unfeasible in humans (Blandini & Armentero,

2012; Chesselet & Richter, 2011; Meredith &

Rademacher, 2011).

In this study, we compared two distinct

bibliography-based AS protocols into the best hearing

mouse strain. The choice of CD1 and C57BL/6 mice

was strategic, as these strains exhibit contrasting

genetic profiles. CD1 mice is a nonconsanguineous

mouse that aimed to mimic the genetic diversity of

the human population.

Despite of that, these distinct genetic

characteristics can influence auditory sensitivity as

CD1 mice exhibited an age-related decline in auditory

sensitivity that has also observed in some studies

(Shone et al., 1991; Wu & Marcus, 2003). On the

other hand, C57BL/6, which provides a more

homogenous genetic background, maintained their

auditory function until 6 months of age. These results

should be treated with caution as other studies have

found C57BL/6 to develops progressive age-related

sensorineural hearing loss (Walton et al., 1995;

Willott, 1986). Perhaps the normal hearing of

C57BL/6 reported in our hands is related to the

specific substrain used. The “Ola” C57BL/6 substrain

was studied in our work whereas, unfortunately, most

studies do not report the specific examined substrains,

which as we have demonstrated here, can influence

hearing outcomes (Mekada et al., 2009).

Our findings also underscore the critical

importance of considering age and strain-specific

differences in auditory processing when designing

preclinical studies. A comprehensive characterization

of mice using objective auditory tests, such as

CAEPs, prior to initiating any auditory stimulation

protocol is essential.

DELTA

BASRP

POST-PRE relative

power difference (%)

-10

0

10

20

THETA

BASRP

-8

-4

0

4

8

ALPHA

BASRP

-16

-12

-8

-4

0

4

8

BETA

BASRP

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

GAMMA

BASRP

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

758

Figure 7: Relative delta (left panel) and gamma (right panel) power at baseline day (D0), pre- (PRE) and post-stimulation

(POST) periods days (D1, D3 and D5) and resting days (D2 and D4) obtained from iEEG recordings of five mice at AS-

protocol 2. Vertical black lines represent auditory stimulation (AS) periods. Data is shown as means ± SEM analyzed from

five mice. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed.

Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy

of prolonged auditory stimulation protocols, lasting

up to two weeks, in inducing long-lasting changes in

brain oscillations (Lee et al., 2018). However, our

study provides a novel perspective by evaluating the

effects of a shorter, more focused stimulation

protocol. By focusing on a shorter stimulation period,

we have been able to determine whether a more

concise intervention is enough to induce the desired

neuronal entrainment. This strategy has several

significant advantages as it allows for a reduction in

the time of exposure to stimulation, minimizing the

risk of adverse effects and facilitating patient

adherence to long-term treatment.

Surprisingly, when faithfully replicating the AS

protocol described Lee et al. (2018) in a mouse model

of AD, we did not observe the same effects in

reducing gamma power in the short-term. In

particular, the claim that 40 Hz pulses were used to

stimulate the auditory system of mice raises

questions. Considering the auditory range of rodents,

stimuli of this frequency are likely not optimal for

inducing significant changes in neuronal activity

(Heffner & Heffner, 2007; Naff et al., 2007;

Ohlemiller et al., 2016). Previous studies have shown

that the use of tones within the auditory range of mice,

combined with frequency modulations, is a more

effective strategy for modulating neuronal activity

(Kilgard et al., 2001; Martorell et al., 2019).

Consequently, we modified AS-protocol 1 exploring

the use of audible tones following with the aim of

optimizing the efficacy of stimulation and replicating

the results reported in peer-reviewed publications.

In contrast, the AS-protocol 2, incorporating a 10

kHz tone presented in 40 Hz auditory pulses, induced

notable changes in EEG power. Specifically, we

observed a significant increase in gamma band power

and a decrease in delta band power that is consistent

with previous studies demonstrating the potential of

AS to enhance cortical excitability and promote

neural synchrony (Gálvez et al., 2018; González et

al., 2023).

The observed increase in gamma power is

particularly intriguing, as gamma oscillations are

implicated in cognitive processes, including

attention, memory, and sensory perception. The

enhancement of gamma power may counteract the

slowing of neural oscillations, a hallmark of PD

(Soikkeli et al., 1991) Furthermore, the persistence of

gamma power enhancement for at least one day post-

stimulation suggests a potential, although reversible,

long-lasting impact of AS on neural networks.

However, further longitudinal studies with

continuous AS are needed to fully elucidate the time

course of these effects and to determine the optimal

stimulation parameters for maximizing therapeutic

benefits.

The reduction in delta power because of AS and

its subsequent recovery to baseline levels is also

noteworthy. Increased delta band power has been

identified as a potential early PD biomarker (Caviness

et al., 2015; Chu et al., 2021) that also associates with

dementia in PD (Bosboom et al., 2006). A study from

Stanley et al. (2019) in rhesus macaque monkey

examined the influence of gamma (40 Hz) click trains

on delta transient response followed finding an

entrainment of gamma and suppression of delta. Also,

D0

D1-PRE

D1-POST

D2

D3-PRE

D3-POST

D4

D5-PRE

D5-POST

Relative delta power (%)

20

30

40

50

D0

D1-PRE

D1-POST

D2

D3-PRE

D3-POST

D4

D5-PRE

D5-POST

Relative gamma power (%)

0

5

10

15

Modulating Cerebral Rhythms in Parkinson’s Disease: Insights on the Role of Auditory Stimulation

759

a construction of a computational model determined

that long duration gamma-rhythmic input stimuli

induce a steady-state containing entrainment at

gamma, and suppression of delta oscillations. This

suppression is achieved in the model by an action

driven by the thalamus.

Several limitations in this study warrant careful

attention. First, SPL used in AS protocols may be

high. Consequently, assessing auditory thresholds

before starting AS will improve animal welfare.

Second, given the potential for distortion in

conventional audio equipment, future studies should

rigorously control frequency behavior. Future

research will also refine AS-protocol 2 and

investigate the neural mechanisms modulated by AS

during the ON period. Further investigation should

focus on the therapeutic potential of the AS protocol

in PD models, particularly targeting early

pathological EEG biomarkers for timely intervention.

In conclusion, while our findings offer compelling

evidence supporting the capacity of AS to modulate

neural oscillatory activity in a preclinical PD model,

additional studies are imperative to delineate the

specific neural dynamics induced by AS and to

evaluate its long-term therapeutic efficacy.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this study represents a significant step

in elucidating and detailing an effective AS protocol

for PD. Our findings demonstrate that AS with 10

kHz tones presented with 40 Hz pulses can induce a

reduction in delta power and an increase in gamma

power, in the unmodified brain. AS-based

technologies could theoretically counteract EEG

changes linked with injury and neurodegeneration.

Our results reinforce the pathway toward the

identification of specific, increasingly optimized AS

paradigms for the treatment of PD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Soledad Martinez for the excellent

technical assistance. This study was partially funded

by the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (PID2023-

152058OB-I00) funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/

501100011033), Comunidad de Madrid (MINA-CM-

S2022/BMD-7236 and PEJ-2023-AI/SAL-GL-

26815) and the European Union's EIC-Pathfinder

Program, under the project THOR (Grant Agreement

number 101099719).

REFERENCES

Adaikkan, C., & Tsai, L. (2020). Gamma entrainment:

Impact on neurocircuits, glia, and therapeutic

opportunities. Trends in Neurosciences, 43(1), 24–41.

10.1016/j.tins.2019.11.001

Ahveninen, J., Kähkönen, S., Tiitinen, H., Pekkonen, E.,

Huttunen, J., Kaakkola, S., Ilmoniemi, R. J., &

Jääskeläinen, I. P. (2000). Suppression of transient 40-

hz auditory response by haloperidol suggests

modulation of human selective attention by dopamine

D2 receptors. Neuroscience Letters, 292(1), 29–32.

10.1016/S0304-3940(00)01429-4

Albouy, P., Martinez-Moreno, Z. E., Hoyer, R. S., Zatorre,

R. J., & Baillet, S. (2022). Supramodality of neural

entrainment: Rhythmic visual stimulation causally

enhances auditory working memory performance.

Science Advances, 8(8), eabj9782. 10.1126/sciadv.

abj9782

Barios, J. A., Pisarchyk, L., Fernandez-Garcia, L., Barrio,

L. C., Ramos, M., Martinez-Murillo, R., & Gonzalez-

Nieto, D. (2016). Long-term dynamics of

somatosensory activity in a stroke model of distal

middle cerebral artery oclussion. Journal of Cerebral

Blood Flow and Metabolism: Official Journal of the

International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and

Metabolism, 36(3), 606–620. 10.1177/0271678X1560

6139

Benninger, D. H., Lomarev, M., Lopez, G., Wassermann,

E. M., Li, X., Considine, E., & Hallett, M. (2010).

Transcranial direct current stimulation for the treatment

of parkinson's disease. Journal of Neurology,

Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 81(10), 1105–1111.

10.1136/jnnp.2009.202556

Benoit, C., Dalla Bella, S., Farrugia, N., Obrig, H., Mainka,

S., & Kotz, S. A. (2014). Musically cued gait-training

improves both perceptual and motor timing in

parkinson's disease. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience,

8, 494. 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00494

Blandini, F., & Armentero, M. (2012). Animal models of

parkinson's disease. The FEBS Journal, 279(7), 1156–

1166. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08491.x

Bosboom, J. L. W., Stoffers, D., Stam, C. J., van Dijk, B.

W., Verbunt, J., Berendse, H. W., & Wolters, E. C.

(2006). Resting state oscillatory brain dynamics in

parkinson's disease: An MEG study. Clinical

Neurophysiology: Official Journal of the International

Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology, 117(11),

2521–2531. 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.06.720

Bukowska, A. A., Krężałek, P., Mirek, E., Bujas, P., &

Marchewka, A. (2015). Neurologic music therapy

training for mobility and stability rehabilitation with

parkinson's disease - A pilot study. Frontiers in Human

Neuroscience, 9, 710. 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00710

Caviness, J. N., Hentz, J. G., Belden, C. M., Shill, H. A.,

Driver-Dunckley, E. D., Sabbagh, M. N., Powell, J. J.,

& Adler, C. H. (2015). Longitudinal EEG changes

correlate with cognitive measure deterioration in

parkinson's disease. Journal of Parkinson's Disease,

5(1), 117–124. 10.3233/JPD-140480

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

760

Chan, D., Suk, H., Jackson, B. L., Milman, N. P., Stark, D.,

Klerman, E. B., Kitchener, E., Fernandez Avalos, V. S.,

de Weck, G., Banerjee, A., Beach, S. D., Blanchard, J.,

Stearns, C., Boes, A. D., Uitermarkt, B., Gander, P.,

Howard, M., Sternberg, E. J., Nieto-Castanon, A., . . .

Tsai, L. (2022). Gamma frequency sensory stimulation

in mild probable alzheimer's dementia patients: Results

of feasibility and pilot studies. PloS One, 17(12),

e0278412. 10.1371/journal.pone.0278412

Chesselet, M., & Richter, F. (2011). Modelling of

parkinson's disease in mice. The Lancet. Neurology,

10(12), 1108–1118. 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70227-7

Chu, C., Zhang, Z., Wang, J., Liu, S., Wang, F., Sun, Y.,

Han, X., Li, Z., Zhu, X., & Liu, C. (2021). Deep

learning reveals personalized spatial spectral

abnormalities of high delta and low alpha bands in EEG

of patients with early parkinson’s disease. Journal of

Neural Engineering, 18(6), 066036. 10.1088/1741-

2552/ac40a0

Fernández-García, L., Marí-Buyé, N., Barios, J. A.,

Madurga, R., Elices, M., Pérez-Rigueiro, J., Ramos, M.,

Guinea, G. V., & González-Nieto, D. (2016). Safety

and tolerability of silk fibroin hydrogels implanted into

the mouse brain. Acta Biomaterialia, 45, 262–275.

10.1016/j.actbio.2016.09.003

Fernández-García, L., Pérez-Rigueiro, J., Martinez-

Murillo, R., Panetsos, F., Ramos, M., Guinea, G. V., &

González-Nieto, D. (2018). Cortical reshaping and

functional recovery induced by silk fibroin hydrogels-

encapsulated stem cells implanted in stroke animals.

Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 12, 296.

10.3389/fncel.2018.00296

Fernández-Serra, R., Martínez-Alonso, E., Alcázar, A.,

Chioua, M., Marco-Contelles, J., Martínez-Murillo, R.,

Ramos, M., Guinea, G. V., & González-Nieto, D.

(2022). Postischemic neuroprotection of

aminoethoxydiphenyl borate associates shortening of

peri-infarct depolarizations. International Journal of

Molecular Sciences, 23(13), 7449.

10.3390/ijms23137449

Fujiki, M., Yee, K. M., & Steward, O. (2020). Non-invasive

high frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic

stimulation (hfrTMS) robustly activates molecular

pathways implicated in neuronal growth and synaptic

plasticity in select populations of neurons. Frontiers in

Neuroscience, 14, 558. 10.3389/fnins.2020.00558

Gálvez, G., Recuero, M., Canuet, L., & Del-Pozo, F.

(2018). Short-term effects of binaural beats on EEG

power, functional connectivity, cognition, gait and

anxiety in parkinson's disease. International Journal of

Neural Systems, 28(5), 1750055. 10.1142/S01290657

17500551

García-Peña, P., Ramos, M., López, J. M., Martinez-

Murillo, R., de Arcas, G., & Gonzalez-Nieto, D. (2023).

Preclinical examination of early-onset thalamic-cortical

seizures after hemispheric stroke. Epilepsia, 64(9),

2499–2514. 10.1111/epi.17675

González, D., Bruña, R., Martínez-Castrillo, J. C., López, J.

M., & de Arcas, G. (2023). First longitudinal study

using binaural beats on parkinson disease. International

Journal of Neural Systems, 33(6), 2350027.

10.1142/S0129065723500272

Goodwill, A. M., Lum, J. A. G., Hendy, A. M., Muthalib,

M., Johnson, L., Albein-Urios, N., & Teo, W. (2017).

Using non-invasive transcranial stimulation to improve

motor and cognitive function in parkinson's disease: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific

Reports, 7(1), 14840. 10.1038/s41598-017-13260-z

Heffner, H. E., & Heffner, R. S. (2007). Hearing ranges of

laboratory animals. Journal of the American

Association for Laboratory Animal Science: JAALAS,

46(1), 20–22.

Henao, D., Navarrete, M., Valderrama, M., & Le Van

Quyen, M. (2020). Entrainment and synchronization of

brain oscillations to auditory stimulations.

Neuroscience Research, 156, 271–278. 10.1016/j.neur

es.2020.03.004

Herrero, M. A., Gallego, R., Ramos, M., Lopez, J. M., de

Arcas, G., & Gonzalez-Nieto, D. (2021). Sleep-wake

cycle and EEG-based biomarkers during late neonate to

adult transition. Brain Sciences, 11(3), 298.

10.3390/brainsci11030298

Iaccarino, H. F., Singer, A. C., Martorell, A. J., Rudenko,

A., Gao, F., Gillingham, T. Z., Mathys, H., Seo, J.,

Kritskiy, O., Abdurrob, F., Adaikkan, C., Canter, R. G.,

Rueda, R., Brown, E. N., Boyden, E. S., & Tsai, L.

(2016). Gamma frequency entrainment attenuates

amyloid load and modifies microglia. Nature,

540(7632), 230–235. 10.1038/nature20587

Ingendoh, R. M., Posny, E. S., & Heine, A. (2023). Binaural

beats to entrain the brain? A systematic review of the

effects of binaural beat stimulation on brain oscillatory

activity, and the implications for psychological research

and intervention. Plos One, 18(5), e0286023.

10.1371/journal.pone.0286023

Kilgard, M. P., Pandya, P. K., Vazquez, J., Gehi, A.,

Schreiner, C. E., & Merzenich, M. M. (2001). Sensory

input directs spatial and temporal plasticity in primary

auditory cortex. Journal of Neurophysiology, 86(1),

326–338. 10.1152/jn.2001.86.1.326

Lee, J., Ryu, S., Kim, H., Jung, J., Lee, B., & Kim, T.

(2018). 40 hz acoustic stimulation decreases amyloid

beta and modulates brain rhythms in a mouse model of

alzheimer’s disease.10.1101/390302

Li, S., Ma, L., Wang, Y., Wang, X., Li, Y., & Qin, L.

(2018). Auditory steady-state responses in primary and

non-primary regions of the auditory cortex in neonatal

ventral hippocampal lesion rats. PloS One, 13(2),

e0192103. 10.1371/journal.pone.0192103

Liu, S., Lei, Q., Liu, Y., Zhang, X., & Li, Z. (2022).

Acoustic stimulation improves memory and reverses

the contribution of chronic sleep deprivation to

pathology in 3xTgAD mice. Brain Sciences, 12(11),

1509. 10.3390/brainsci12111509

Martorell, A. J., Paulson, A. L., Suk, H., Abdurrob, F.,

Drummond, G. T., Guan, W., Young, J. Z., Kim, D. N.,

Kritskiy, O., Barker, S. J., Mangena, V., Prince, S. M.,

Brown, E. N., Chung, K., Boyden, E. S., Singer, A. C.,

& Tsai, L. (2019). Multi-sensory gamma stimulation

ameliorates alzheimer's-associated pathology and

Modulating Cerebral Rhythms in Parkinson’s Disease: Insights on the Role of Auditory Stimulation

761

improves cognition. Cell, 177(2), 256–271.e22.

10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.014

Mei, L., Liu, L., Chen, K., & Zhao, H. (2021). Early

functional and cognitive declines measured by

auditory-evoked cortical potentials in mice with

alzheimer's disease. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience,

13, 710317. 10.3389/fnagi.2021.710317

Mekada, K., Abe, K., Murakami, A., Nakamura, S., Nakata,

H., Moriwaki, K., Obata, Y., & Yoshiki, A. (2009).

Genetic differences among C57BL/6 substrains.

Experimental Animals, 58(2), 141–149. 10.1538/expani

m.58.141

Meredith, G. E., & Rademacher, D. J. (2011). MPTP mouse

models of parkinson's disease: An update. Journal of

Parkinson's Disease, 1(1), 19–33. 10.3233/JPD-2011-

11023

Miladinović, A., Ajčević, M., Busan, P., Jarmolowska, J.,

Deodato, M., Mezzarobba, S., Battaglini, P. P., &

Accardo, A. (2021). EEG changes and motor deficits in

parkinson’s disease patients: Correlation of motor

scales and EEG power bands. Procedia Computer

Science, 192, 2616–2623. 10.1016/j.procs.2021.09.031

Murdock, M. H., Yang, C., Sun, N., Pao, P., Blanco-Duque,

C., Kahn, M. C., Kim, T., Lavoie, N. S., Victor, M. B.,

Islam, M. R., Galiana, F., Leary, N., Wang, S., Bubnys,

A., Ma, E., Akay, L. A., Sneve, M., Qian, Y., Lai, C., .

. . Tsai, L. (2024). Multisensory gamma stimulation

promotes glymphatic clearance of amyloid. Nature,

627(8002), 149–156. 10.1038/s41586-024-07132-6

Naff, K. A., Riva, C. M., Craig, S. L., & Gray, K. N. (2007).

Noise produced by vacuuming exceeds the hearing

thresholds of C57Bl/6 and CD1 mice. Journal of the

American Association for Laboratory Animal Science:

JAALAS, 46(1), 52–57.

Nakao, K., & Nakazawa, K. (2014). Brain state-dependent

abnormal LFP activity in the auditory cortex of a

schizophrenia mouse model. Frontiers in

Neuroscience, 8, 168. 10.3389/fnins.2014.00168

Ohlemiller, K. K., Jones, S. M., & Johnson, K. R. (2016).

Application of mouse models to research in hearing and

balance. JARO: Journal of the Association for Research

in Otolaryngology, 17(6), 493. 10.1007/s10162-016-

0589-1

Ross, B., & Lopez, M. D. (2020). 40-hz binaural beats

enhance training to mitigate the attentional blink.

Scientific Reports, 10(1), 7002. 10.1038/s41598-020-

63980-y

Shone, G., Raphael, Y., & Miller, J. M. (1991). Hereditary

deafness occurring in cd/1 mice. Hearing Research,

57(1), 153–156. 10.1016/0378-5955(91)90084-m

Soikkeli, R., Partanen, J., Soininen, H., Pääkkönen, A., &

Riekkinen, P. (1991). Slowing of EEG in parkinson's

disease. Electroencephalography and Clinical

Neurophysiology, 79(3), 159–165. 10.1016/0013-

4694(91)90134-P

Stanley, D. A., Falchier, A. Y., Pittman-Polletta, B. R.,

Lakatos, P., Whittington, M. A., Schroeder, C. E., &

Kopell, N. J. (2019, October 22). Flexible reset and

entrainment of delta oscillations in primate primary

auditory cortex: Modeling and experiment., 812024.

Steinmetz, J. D., Seeher, K. M., Schiess, N., Nichols, E.,

Cao, B., Servili, C., Cavallera, V., Cousin, E., Hagins,

H., Moberg, M. E., Mehlman, M. L., Abate, Y. H.,

Abbas, J., Abbasi, M. A., Abbasian, M., Abbastabar,

H., Abdelmasseh, M., Abdollahi, M., Abdollahi, M., . .

. Dua, T. (2024). Global, regional, and national burden

of disorders affecting the nervous system, 1990–2021:

A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease

study 2021. The Lancet Neurology, 23(4), 344–381.

10.1016/S1474-4422(24)00038-3

Walton, J. P., Frisina, R. D., & Meierhans, L. R. (1995).

Sensorineural hearing loss alters recovery from short-

term adaptation in the C57BL/6 mouse. Hearing

Research, 88(1-2), 19–26. 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00

093-j

Will, U., & Berg, E. (2007). Brain wave synchronization

and entrainment to periodic acoustic stimuli.

Neuroscience Letters, 424(1), 55–60.

10.1016/j.neulet.2007.07.036

Willott, J. F. (1986). Effects of aging, hearing loss, and

anatomical location on thresholds of inferior colliculus

neurons in C57BL/6 and CBA mice. Journal of

Neurophysiology, 56(2), 391–408.

10.1152/jn.1986.56.2.391

Wu, T., & Marcus, D. C. (2003). Age-related changes in

cochlear endolymphatic potassium and potential in CD-

1 and CBA/CaJ mice. Journal of the Association for

Research in Otolaryngology: JARO, 4(3), 353–362.

10.1007/s10162-002-3026-6

Ye, X., Li, L., He, R., Jia, Y., & Poon, W. (2022). Rhythmic

auditory stimulation promotes gait recovery in

parkinson's patients: A systematic review and meta-

analysis. Frontiers in Neurology, 13, 940419.

10.3389/fneur.2022.940419

Zhang, J., Wang, T., Zhang, C., Zeljic, K., Zhan, S., Sun,

B., & Li, D. (2017). The safety issues and hardware-

related complications of deep brain stimulation therapy:

A single-center retrospective analysis of 478 patients

with parkinson’s disease. Clinical Interventions in

Aging, 12, 923. 10.2147/CIA.S130882

Zheng, L., Yu, M., Lin, R., Wang, Y., Zhuo, Z., Cheng, N.,

Wang, M., Tang, Y., Wang, L., & Hou, S. (2020).

Rhythmic light flicker rescues hippocampal low

gamma and protects ischemic neurons by enhancing

presynaptic plasticity. Nature Communications, 11(1),

3012. 10.1038/s41467-020-16826-0

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

762