The Role of Self-Focusing During the Laser Microstructuring in the

Volume of Fused Silica

Anna V. Bogatskaya

1,2 a

, Ekaterina A. Volkova

3b

and Alexander M. Popov

1,2 c

1

Department of Physics, Lomonosov Moscow State University, 119991, Moscow, Russia

2

Lebedev Physical Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, 119991, Moscow, Russia

3

Skobeltsyn Institute of Nuclear Physics, Lomonosov Moscow State University, 119991, Moscow, Russia

Keywords: Laser Microstructuring in Dielectrics, Birefringent Nanolattices, Fused Silica,

Multiphoton Ionization of Dielectrics, Plasma Formation, Numerical Modelling, Wave Equation.

Abstract: In this study we perform 3D self-consistent numerical simulations of a focused laser pulse exposure in the

bulk of fused silica. The model combines the second-order wave equation in cylindrical coordinates with a

rate equation for the density of charge carriers in the conduction band. Our results indicate that a dense plasma

formation near the focal plane effectively scatters and reflects the laser pulse. The coherent interference

between the incident and scattered laser waves creates regions of intense field ionization, resulting in periodic

plasma nanostructures along both the ρ- and z-axes. We also examine the impact of nonlinear refractive index

effects, which lead to pulse self-focusing. We should note that similar subwavelength, divergent structures in

material modification regions have been observed in recent experiments conducted under comparable laser

focusing conditions.

1 INTRODUCTION

In recent years, substantial research has been

dedicated to investigating the complex, multi-level

processes that modify the physical characteristics of

materials subjected to tightly focused femtosecond

laser pulses (Gattass and Mazur, 2008; Taylor et al.,

2007; Bulgakova et al., 2015). State-of-the-art

ultrafast laser systems have revealed new

mechanisms in how electromagnetic fields, plasma,

and materials interact. These interactions drive

various structural changes in transparent dielectric

materials, such as the formation of micro- and

nanoscale voids, densification zones, micro-tracks

(Shimotsuma et al., 2005; Sun et al., 2007; Beresna et

al., 2011; Dai et al., 2016; Mizeikis et al., 2009), as

well as periodic refractive index shifts (Schaffer et al.,

2001; Wang et al., 2007; Mermillod-Blondin et al.,

2008) and other effects.

One of the most notable achievements has been

the development of periodic subwavelength

structures with high optical contrast between

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1538-3433

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4883-3349

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7300-3785

modified zones, which are particularly promising for

applications in optical memory, micro-photonic

crystals, optical couplers, binary storage, and other

fields (Musgraves et al., 2011; Tan et al., 2016).

Among these materials, fused silica glass has become

especially important since the groundbreaking work

of (Shimotsuma et al. 2003), which first introduced

the concept of birefringent volume nanogratings in

this medium. Subsequent research by various groups

(Desmarchelier et al., 2015; Bulgakova et al., 2013)

has highlighted key mechanisms involved in creating

these structures. These mechanisms include coupling

between electron plasma waves and incident light

(Shimotsuma et al., 2005; Shimotsuma et al., 2003),

the formation of nanoplasmas due to field localization

and their self-organization into nanoscale patterns

(Bhardwaj et al., 2006; Taylor et al., 2008), and the

confinement and clustering of exciton-polaritons

(Beresna et al., 2012). However, the lack of

comprehensive theoretical models to confirm each

proposed mechanism, as well as an incomplete

understanding of the necessary conditions, still

120

Bogatskaya, A. V., Volkova, E. A. and Popov, A. M.

The Role of Self-Focusing During the Laser Microstructuring in the Volume of Fused Silica.

DOI: 10.5220/0013248900003902

In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Photonics, Optics and Laser Technology (PHOTOPTICS 2025), pages 120-125

ISBN: 978-989-758-736-8; ISSN: 2184-4364

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

presents challenges to the controlled and precise laser

fabrication of these complex volume nanopatterns.

In this work, we carry out fully self-consistent 3D

numerical simulations of the propagation of an

intense, tightly focused Yb-doped fiber laser pulse

( 𝜆

=1030 nm) in fused silica, alongside the

dynamics of laser-induced solid-state plasma. The

simulations explore a range of pulse durations, peak

intensities, and focusing parameters. By including the

curvature of the incident laser pulse front and

considering scattering and diffraction effects in

cylindrical geometry, we identified a new mechanism

of plasma self-organization in conditions of tight laser

beam focusing. The findings reveal that dense plasma

formation near the focal area effectively scatters the

laser wave. Due to the interference between the

incident plane wave and the reflected, highly non-

planar wave in the pre-focal area, a detailed pattern of

laser field amplitude peaks and troughs emerges,

leading to a structured subwavelength plasma

distribution. It is important to note that such

mechanism of laser nanostructuring has not been

mentioned in previous studies, which certainly opens

up prospects for further progress in the area of

controlled laser writing in the volume of transparent

dielectrics. We also examine the effect of refractive

index nonlinearity which can lead to partial self-

focusing compensating the pulse defocusing by

plasma electrons.

2 MODELLING AND METHODS

Our modelling involves solving the second-order

wave equation for a focused linearly polarized laser

pulse moving through the fused silica in a cylindrical

geometry:

𝜌

+

=

с

+

. (1)

In this equation, 𝐸=𝐸(𝜌,𝑧,𝑡) denotes the electric

field strength of the laser pulse as it propagates in the

z-direction, 𝑛 is the fused silica refractive index

which includes both linear and nonlinear terms: 𝑛=

𝑛

+𝑛

𝐼. Here 𝑛

=1.45 is the linear part of the

refractive index, while the second term being

proportional to laser intensity 𝐼

(

𝜌,𝑧,𝑡

)

stands for the

cubic nonlinearity. According to (Vermeulen et al,

2023) we put 𝑛

=2.23×10

cm

2

/W. The second

term 𝑗(𝜌,𝑧,𝑡) in right part of equation (2) is the field

induced electron current. This current includes

contributions from both the polarization of charge

carriers within the conduction band and ionization

effects caused by transitions from the valence band to

the conduction band. Both of these currents depend

on the evolution of electron density 𝑛

(𝜌,𝑧,𝑡) within

the conduction band, governed by the following

equation:

𝜕𝑛

𝜕𝑡

=𝐷

1

𝜌

𝜕

𝜕𝜌

𝜌

𝜕𝑛

𝜕𝜌

+

𝜕

𝑛

𝜕𝑧

+𝑊

(

𝐼

)(

𝑁

−𝑛

)

+𝜈

(

𝐼

)

𝑛

1 −

𝑛

𝑁

−

𝑛

𝜏

(2)

Here 𝐷 ≈300 cm

2

/s is the electron diffusion

coefficient, 𝜏

=150 fs is the average electron

recombination time (Audebert, et. al., 1990), 𝑊

(

𝐼

)

and 𝜈

(𝐼) represent the rates of field-driven and

electron-impact ionization, 𝐼(𝜌,𝑧,𝑡) is the laser

radiation intensity, 𝑁

=2.1∙10

см

-3

is an atomic

density of fused silica. The laser intensity 𝐼

(

𝜌,𝑧,𝑡

)

is

derived from the electric field as follows: 𝐼

(

𝜌,𝑧,𝑡

)

=

〈

𝑛

𝐸

(

𝜌,𝑧,𝑡

)〉

, where brackets mean averaging

over the period of wave field oscillations. To

calculate the ionization probability we utilize the

general Keldysh formula (Keldysh, 1964;

Bogatskaya, et. al., 2023).

To account for the energy losses of the laser pulse

due to the field ionization process, we introduce an

ionization current 𝑗

(𝑧,𝑡) on the right side of Eq.

(1). This current can be expressed as

𝑗

(

𝜌,𝑧,𝑡

)

=

〈

〉

=

(3)

=

〈

〉

𝑊

𝐼

(

𝜌,𝑧,𝑡

)

(𝑁

−𝑛

(

𝜌,𝑧,𝑡

)

),

where 𝜕𝑛

𝜕𝑡

⁄

is the rate of electron density

production due to field ionization,

〈

𝐸

〉

is an averaged

over the period field

|

𝐸

(

𝜌,𝑧,𝑡

)|

. One should also

consider the polarization current 𝑗

(𝜌,𝑧,𝑡) of

electrons in the conduction band, which is induced by

the laser pulse. This current can be described via the

Drude model:

+𝜈

𝑗

=

∗

𝐸

(

𝜌,𝑧,𝑡

)

. (4)

Here 𝜈

≈2×10

s

-1

is the transport

collisional frequency. Total current in (1) reads

𝑗=𝑗

+𝑗

. (5)

The electron impact ionization is also included in

the right part of equation (2). The frequency of

electron impact ionization is expressed in terms

[Raizer. 1977]:

𝜈

(𝐼)=

(

,,

)

∗

. (6)

The Role of Self-Focusing During the Laser Microstructuring in the Volume of Fused Silica

121

Here 𝑚

∗

=0.5𝑚

is the effective mass of charge

carriers in fused silica, 𝜔 ≈1.83× 10

s

-1

is the

laser frequency corresponding to 𝜆

=1030 nm.

Our simulations use laser pulses with Gaussian

radial profiles at the focal plane 𝑧=0

( 𝐸~𝑒𝑥𝑝

(

−(𝜌 𝜌

⁄

)

)

and sin-squared temporal

envelope (𝐸~𝐸

𝑠𝑖𝑛

,𝑡∈(0,𝜏

)). To obtain

such pulse, the wave equation similar to (1) but

without the term of the electric current in the right-

hand part was integrated with zero initial conditions

for electric field strength and its derivative over time

and the boundary condition at 𝑧=0:

𝜕𝐸

(

𝜌,𝑧,𝑡

)

𝜕𝑧

=

𝜔𝑛

𝑐

𝐸

exp

(

−

(

𝜌𝜌

⁄)

)

𝑠𝑖𝑛

𝜋𝑡

𝜏

cos

(

𝜔𝑡

)

,

𝑡∈0

∗

,𝜏

(7)

𝜕𝐸

(

𝜌,𝑧= 0,𝑡

)

𝜕𝑧

=0, 𝑡>𝜏

The obtained pulse is considered to be the initial

one in further simulations. If one reverses the time

scale, this pulse will move back in negative direction

towards the focal plane 𝑧=0.

The focal spot radius varies from 𝜌

=1.7 to 3

mkm, while the pulse duration ranges from 𝜏

=12.5

to 75 fs. These parameters correspond to pulse

focusing within the fused silica volume with no initial

free charge carriers. The spatial pulse length falls

within ℓ

=

(

𝑐𝑛

⁄)

𝜏

~2.5 − 15 mkm. For pulses

with a 50 fs duration and focal radius 𝜌

=2.5 mkm

the energy range was set to 0.024 – 0.34 mkJ, yielding

peak intensities of approximately ~5 × 10

−7×

10

W/cm

2

at the focal plane (here we again neglect

the birth of electron density in the focal plane region

leading to the defocusing as a consequence, a decrease

in focal intensity). For considered pulse parameters, the

rate of field ionization dominates in comparison with

electron impact ionization (Bogatskaya et al, 2023).

Therefore, the electron avalanche, commonly seen in

breakdown processes in gases and solids over

microsecond and nanosecond timescales, does not

control the plasma dynamics in this case. The

equations (1) and (2) were solved jointly within the

spatial domain

𝜌,𝑧

=

0−𝜌

,0−𝐿

with 𝜌

=

30 mkm and, 𝐿=120 mkm. Initial pulse (𝑡=0) was

centered around 𝑧

≈105 µm and propagated in the

negative z-direction, achieving peak focus close to the

origin ( 𝑧=30 mkm). The numerical integration

approach for the second-order wave equation is briefly

described in (Bogatskaya et al, 2019).

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

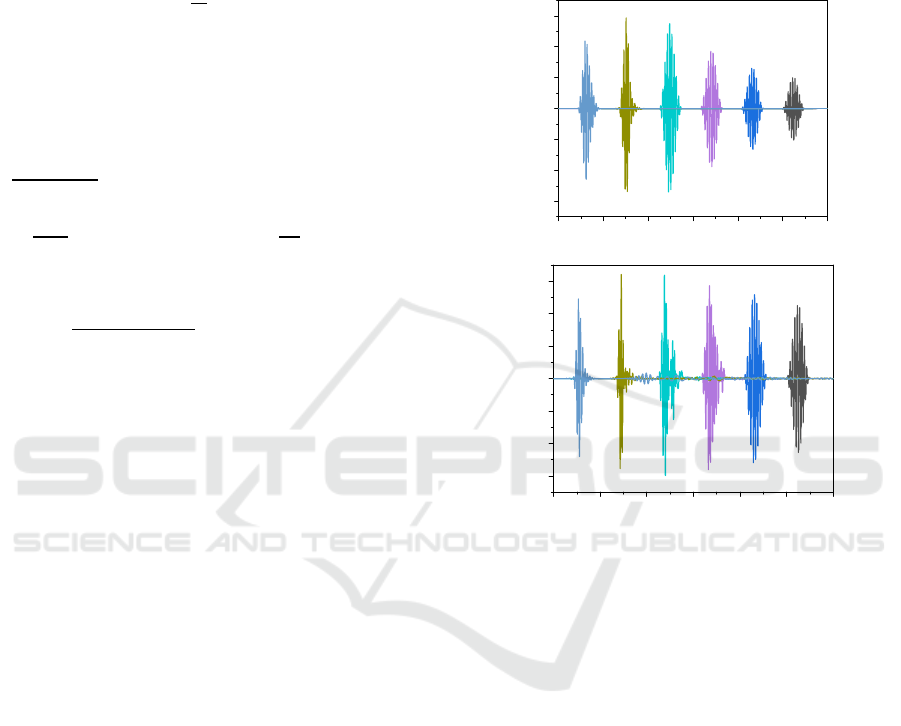

We start our analysis with the data on pulse focusing

during the propagation in the bulk of fused silica. In

Fig.1 we perform the simulations of on-axis field

distributions for two values of laser peak intensity.

0 20 40 60 80 100 120

-1.0

-0.7

-0.3

0.0

0.3

0.7

1.0

E(z,t,

1

=0), arb.un.

z, mkm

a

020406080100120

-1.0

-0.7

-0.3

0.0

0.3

0.7

1.0

E(z,t,

−

=0), arb.un.

z

, mkm

b

Figure 1: On-axis electric field distributions for different

instants of time (intervals between time points ~ 0.1 ps).

The pulse moves from right to left and focuses at point 𝑧=

30 mkm. Pulse peak intensity is 10

W/cm

2

(a), 5·10

W/cm

2

(b). Focal spot radius is 𝜌

=2.5 mkm, pulse

duration is 50 fs.

One can see that for more intense laser pulse

strong defocusing takes place due to the formation of

dense plasma near the focal area. Indeed, the

distributions of electron concentration for the

intensity 5·10

W/cm

2

(see Fig.2) indicate the

values of electron density more than 10

cm

-3

. In

this case plasma electrons significantly defocuses and

reflects laser radiation, which results in appearing

rather regular structures both in the 𝜌- and z-axis

direction. The formation of such patterns can be

attributed to the coherent interference between a

nearly planar incident wave in the pre-focal region

and a significantly non-planar (almost spherical)

wave scattered by a dense plasma burst [Bogatskaya,

et al, 2024].

PHOTOPTICS 2025 - 13th International Conference on Photonics, Optics and Laser Technology

122

Figure 2: Profiles of electron density in the volume of fused silica formed by the 50-fs laser pulse with the peak intensity

5·10^13 W/cm2 (pulse energy is 0.24 mkJ). Graph (a) represents data in the absence of self-focusing effect, (b) – accounting

the self-focusing effect. Focal spot radius is ρ_0=2.5 mkm, the position of focal plane is 30 mkm.

In Fig.2 we also analyze the effect of refractive index

nonlinearity on the plasma microstructures formation.

In particular, Fig 2b presents simulations accounting

𝑛

. Simulations have shown that in the absence of

electrons the threshold of self-focusing in fused silica

is about 6 MW. However, due to the strong

defocusing of plasma electrons, the presence of self-

focusing induced by the nonlinear refractive index

has little effect on the overall picture of plasma

formations. Thus, in Figure 2b one can observe that

considering nonlinearity leads to a slight increase in

the electron concentration in the paraxial zone near

the focus.

The effect of electrons on the laser beam focusing

can be clearly observed in Figure 3, which shows the

dependence of the mean radius of the laser pulse

during its propagation for different pulse intensities.

We calculate this radius, using the following formula:

〈

𝜌(𝑡)

〉

=

(,,)

(,,)

. (7)

At the initial instant of time the pulse is located at the

point 𝑧=105 mkm and moves from right to left

towards the focal plane at 𝑧=30 mkm. Curve 1

corresponds to the low energy pulse propagation in

the absence of ionization. It can be seen that an

increase of pulse energy leads to an increase in the

observed beam size and a shift in the position the

focal plane (minimum value of

〈

𝜌

〉

). An increase in

the focal spot size leads to a decrease in the peak

intensity of the beam, as a result, ionization saturation

occurs in the sample volume. This effect has been

repeatedly mentioned in a number of works on

focused radiation exposure in solid dielectrics

(Zheltikov, 2009; Rudenko, et al, 2023).

0.0

2.0x10

-13

4.0x10

-13

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

2

3

<ρ>, mkm

propagation time, s

1

Figure 3: The radial size of the pulse

〈

𝜌

〉

during its

propagation for different pulse intensities: 1 – weak pulse,

no plasma formation, 2 - 10

W/cm

2

, 3 - 6·10

W/cm

2

.

Plasma-free focal spot radius is 𝜌

=2.5 mkm, pulse

duration is 50 fs.

This study focuses on the consideration of linear

polarization of the laser pulse, however, the influence

of polarization on the femtosecond laser writing

20 40 60 80

0.00025

0.00056

0.00088

z, mkm

ρ, mkm

0.0

3.0x10

19

6.0x10

19

9.0x10

19

1.2x10

20

1.5x10

20

n

e

, cm

-3

a

20 40 60 80

0.00025

0.00056

0.00088

z, mkm

ρ

, mkm

0.0

3.0x10

19

6.0x10

19

9.0x10

19

1.2x10

20

1.5x10

20

n

e

, cm

-3

b

The Role of Self-Focusing During the Laser Microstructuring in the Volume of Fused Silica

123

process has been investigated in several experimental

studies. For example, in (Lei et al, 2023) they showed

that, contrary to intuitive expectations, ultrafast laser

direct writing with elliptical polarization in silica

glass results in birefringence approximately twice as

large as that observed with linearly polarized light,

although nonlinear absorption in the case of elliptical

polarization is about 2.5 times weaker. Moreover, the

use of laser pulses with different polarizations allows

for the creation of more complex nanostructure

topologies. However, the lack of theoretical studies at

present complicates the possibility of controlled

polarization-dependent laser writing of

nanostructures.

4 CONCLUSIONS

We performed the numerical study of the effect of

dense plasma formation in the volume of fused silica

exposed by intense tightly focused femtosecond IR

laser pulse. It was demonstrated that the plasma

object with electron density at a level ~1 − 2 × 10

cm

-3

arises in the pre-focal plane under the conditions

of tight focusing. The formed plasma effectively

scatters the incident femtosecond laser pulse

producing the region of effective wave interference.

As a result, the spatial distribution of the electron

production rate is characterized by rather sharp

maxima located in the bunches of the standing wave.

These maxima lead to the formation of periodic

subwavelength regions of dense plasma both in ρ- and

z-directions. It is important to note that the identified

mechanism of volumetric self-organization is

associated with a strong curvature of the front of the

reflected from plasma laser wave. It was shown that

due to strong beam defocusing by plasma electrons

the effect of pulse self-focusing is negligible.

Importantly, that the obtained profiles of plasma

nanostructures are found to be in good agreement

with SEM images of nanomodifications inscribed in

bulk fused and crystal silica accumulation regime

under the multi-pulse exposure (Zhang et al, 2019;

Gulina et al, 2024). Thus, in the work (Zhang et al,

2019), the formation of periodicity in a quartz crystal

was studied under the exposure of tightly focused

laser pulses with wavelengths of 1030 and 800 nm at

different pulse energies. The results of the experiment

demonstrated the formation of extended quasi-

periodic nanostructures, the spatial dimensions of

which increase with increasing energy input. The

similarity of the formed structures with the structures

written in the volume of fused silica under the

relatively equal laser focusing conditions, given in the

work of (Gulina et al, 2024), indicates the similarity

of the mechanisms of the initial (plasma) stage of the

nanostructuring, but later stages associated with the

formation of various defects and melting zones may

depend on a specific material, which requires further

analysis.

In summary, the importance of understanding the

process of fabrication of such periodic nanopatterns

is determined by their extensive application across

various fields, including optical polarizing elements

and devices, light waveguides, micro-photonic

crystals, binary storage components, and more (Tan

et al., 2016).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was funded by the Russian Science

Foundation (project no. 22-72-10076).

REFERENCES

Audebert, P.; Daguzan, Ph.; Dos Santos, A.; Gauthier, J. C.;

Geindre, J. P.; Guizard, S.; Hamoniaux, G.; Krastev, K.;

Martin, P.; Petite, G.; and Antonetti, A. (1994). Phys.

Rev. Lett., 73 (14), 1990.

Beresna, M.; Gecevičius, M.; Bulgakova, N. M.; Kazansky,

P. G. (2011). Opt. Express, 19, 18989.

Beresna, M.; Gecevičius, M.; Kazansky, P. G.; Taylor, T.;

Kavokin, A. (2012). Appl. Phys. Lett., 101, 053120.

Bhardwaj, V. R.; Simova, E.; Rajeev, P. P.; Hnatovsky, C.;

Taylor, R. S.; Rayner, D. M.; Corkum, P.B. (2006).

Phys. Rev. Lett., 96, 057404.

Bogatskaya, A. V.; Volkova, E. A.; Popov, A. M., (2019).

Laser Phys., 29, 086002.

Bogatskaya, A.; Gulina, Yu.; Smirnov, N.; Gritsenko, I.;

Kudryashov, S.; Popov, A. (2023). Photonics, 10, 515.

Bogatskaya, A. V.; Volkova, E. A.; Popov, A. M., (2024).

EPL, 147 (3), 35001.

Bulgakova, N. M.; Zhukov, V. P.; Meshcheryakov, Yu. P.

(2013). Appl. Phys. B, 113(3), 437-449.

Bulgakova, N. M.; Zhukov, V. P.; Sonina, S. V.;

Meshcheryakov, Y.P. (2015). J. Appl. Phys., 118 (23),

233108.

Dai, Y.; Patel, A.; Song, J.; Beresna, M.; and Kazansky, P.

G. (2016). Opt. Express, 24, 19344

Desmarchelier, R.; Poumellec, B.; Brisset, F.; Mazerat, S.

and Lancry, M. (2015). World Journal of Nano Science

and Engineering, 5, 115-125.

Gattass, R. R. and Mazur, E. (2008). Nature Photonics, 2,

219-225.

Gulina, Yu.; Rupasov, A.; Krasin, G.; Busleev, N.;

Gritsenko, I.; Bogatskaya, A.; Kudryashov, S. (2024).

JETP Lett., 119 (9), 638 – 644.

Keldysh, L.V. (1964). JETP, 20, 1307–1314.

PHOTOPTICS 2025 - 13th International Conference on Photonics, Optics and Laser Technology

124

Kudryashov, S. I.; Danilov, P. A.; Smaev, M. P.; Rupasov,

A. E.; Zolot’ko, A. S.; Ionin A. A.; Zakoldaev, R. A.

(2021). JETP Lett., 113, 493-497.

Kudryashov, S.; Rupasov, A.; Kosobokov, M.;

Akhmatkhanov, A.; Krasin, G.; Danilov, P.; Lisjikh, B.;

Abramov, A.; Greshnyakov, E.; Kuzmin, E.; et al.

(2022). Nanomaterials, 12, 4303.

Kudryashov, S.; Rupasov, A.; Smayev, M.; Danilov, P.;

Kuzmin, E.; Mushkarina, I.; Gorevoy, A.; Bogatskaya,

A.; and Zolot’ko, A. (2023) Nanomaterials, 13(6),

1133.

Lei, Y., Shayeganrad, G., Wang, H. Sakakura, M., Yu, Y.,

Wang, L., Kliukin, D., Skuja, L., Svirko. Y., Kazansky,

P. (2023). Light Sci Appl, 12, 74.

Mazur, E. (2008). Nature Photon, 2, 219–225.

Mermillod-Blondin, A.; Burakov, I. M.; Meshcheryakov,

Y. P.; Bulgakova, N. M.; Audouard, E.; Rosenfeld, A.;

Husakou, A.; Hertel, I. V.; Stoian, R. (2008). Phys. Rev.

B, 77, 104205.

Mizeikis, V.; Juodkazis, S.; Balciunas, T.; Misawa, H.;

Kudryashov, S.I.; Ionin, A.A.; Zvorykin, V.D. (2009).

J. Appl. Phys., 105, 123106.

Musgraves, J.; Richardson, K.; Jain, H. (2011). Opt. Mater.

Express, 1, 921-935.

Raizer. Yu. P. (1977). Laser induced discharge phenomena

(Consultants Bureau, New York)

Rudenko, A.; Moloney, J. M.; and Polynkin, P. (2023).

Phys. Rev. Applied 20, 064035.

Schaffer, C. B.; Brodeur, A.; García, J. F.; Mazur, E.

(2001). Opt. Lett., 26, 93.

Shimotsuma, Y.; Kazansky, P. G.; Qiu, J. R.; Hirao, K.

(2003). Phys. Rev. Lett., 91, 247405.

Shimotsuma, Y.; Hirao, K.; Qiu, J. R.; Kazansky, P. G.

(2005). Modern Phys. Lett. B, 19, 225.

Sun, H.Y.; Song, J.; Li, C.B.; Xu, J.; Wang, X. S.; Cheng,

Y.; Xu, Z. Z.; Qiu, J. R.; Jia, T. (2007). Appl. Phys. A,

88, 285.

Tan, D.; Sharafudeen, K.N.; Yue, Y.; Qiu, J. (2016).

Progress in Materials Science, 76, 154-228.

Taylor, R. S., Hnatovsky, C., Simova, E., Pattathilet, R.

(2007). Optics Letters, 32 (19), 2888-2890.

Taylor, R.; Hnatovsky, C.; Simova, E. (2008). Laser

Photonics Rev., 2, 26.

Vermeulen, N.; Espinosa, D.; Ball, A. et al (2023).

J. Phys.

Photonics, 5, 035001.

Wang, Z.; Sugioka, K.; Hanada, Y.; Midorikawa, K.

(2007). Appl. Phys. A, 88, 699.

Zhang, F.; Nie, Z.; Huang, H.; Ma, L.; Tang, H.; Hao, M.;

Qiu, J. (2019), Opt. Express, 27, 6442-6450.

Zheltikov. A. M. (2009). JETP Lett., 90, 90–95.

The Role of Self-Focusing During the Laser Microstructuring in the Volume of Fused Silica

125