Assessing Goal Disengagement Using a Digital, Card-Based Game:

A Proof of Concept Study

Sebastian Unger

a

, Hana Minařík and Thomas Ostermann

b

Department of Psychology and Psychotherapy, Witten/Herdecke University,

Alfred-Herrhausen-Str. 50, 58448 Witten, Germany

Keywords: Proof of Concept Study, Choice Behavior, Mental Processes, Experimental Game.

Abstract: The distinction between goal engagement (GE) and goal disengagement (GD) as central psychological

processes is supported by several theories of developmental regulation. However, although there has been

research on both, research on GD has been rather neglected, especially when it comes to behavioral methods

for its assessment. The objective of this paper, therefore, is to evaluate the feasibility of such a behavioral

method by placing a homogeneous group of participants in a situation where they need to distinguish whether

the effort to solve a digital, card-based game leads to successful goal achievement or to frustration. The data

from this group revealed no significant differences in the participants' behavior over the course of the game.

Nonetheless, some tendencies in the number of repetitions and the number of cards collected until the

occurrence of a GD could be found when differentiating between participants who adhered to their goals more

persistently and those who disengaged more frequently. Overall, the game may have potential for both

replacing previous assessment methods and identifying suitable individuals for long-term rehabilitation and

behavioral therapies, but further research is required for application in a clinical setting.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background

Several prominent theories of developmental

regulation across the life span distinguish between

goal engagement (GE) and goal disengagement (GD)

as key psychological processes (Haase et al., 2013).

Both have been associated with indicators of

successful aging, depending on individuals’

resources, and opportunity structures (Heckhausen et

al., 2010). However, while GE has been the subject of

extensive research, research on GD has been rather

neglected (Kappes & Schattke, 2022), despite

substantial evidence that GD plays a central role in

benefiting individuals’ well-being (Tomasik et al.,

2010; Wrosch et al., 2003).

Both GE and GD are usually assessed using self-

reports, with their inherent advantages and

disadvantages. Turning to more behavioral methods,

GE is typically assessed by indicators such as

persistence or aspiration level (e.g., DiCerbo, 2014).

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-6251-2923

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2695-0701

Few, if any, behavioral methods are available for

assessing GD. One exception is that of Rühs et al.

(2022), who tested how social rejection in a virtual

ball-tossing game would affect participants’ goal of

becoming a member of a group. However, it must be

pointed out that this method requires multiple

individuals for a measurement, who must also get to

know each other better beforehand to develop the

goal initially. A notable method applicable to single

individuals is that of Freund and Tomasik (2021). Its

focus lies on the process of prioritization by inducing

a goal conflict in a lab-based experiment, forcing

participants to let go of one induced goal in order to

pursue the other. This method, however, relies on the

notion of limited resources in a multiple goal scenario

and it is not clear whether it is useful for the

assessment of an individual’s propensity to disengage

from a single goal. For a single goal scenario, an

outstanding example is a method that analysed GD in

the context of social relationships (Thomsen et al.,

2017). Here, participants are asked to solve a puzzle

after observing a familiar person attempt the task.

698

Unger, S., Mina

ˇ

rík, H., Ostermann and T.

Assessing Goal Disengagement Using a Digital, Card-Based Game: A Proof of Concept Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0013254100003911

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 2: HEALTHINF, pages 698-704

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

However, because solving a puzzle requires a certain

degree of logical thinking, it could introduce

unwanted bias in individuals less proficient in this

skill through various conditions (Baldo et al., 2015;

Morris et al., 1995).

Taken together, the adaptive value of GD has

been shown to be prominent when a goal is

unattainable (Tomasik et al., 2010; Wrosch et al.,

2003). Hence, an individual needs to distinguish

between situations in which increased effort will turn

into successful goal attainment and situations in

which increased effort will only result in frustration.

As there is no all-encompassing method yet, there is

a need for an instrument that confronts individuals

with both types of situations to assess their

competence in distinguishing between them and

drawing appropriate behavioral consequences.

1.2 Objectives of the Paper

The main objective of this paper is to evaluate the

feasibility of a digital, card-based game developed to

assess GD in a situation where increased effort is

likely lead to frustration. To this end, the novel

assessment method and its fundamental parameters

are investigated using a small number of participants.

However, the paper is not solely intended to present

the research results, but also aims to determine

whether further research with this game is

worthwhile.

2 MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1 Participants

For this proof of concept study, a homogeneous group

of participants was recruited at the Witten/Herdecke

University. The group consisted of 50 psychology

students (41 women and 9 men), all of whom were

over 18 years old and had no limitations in hearing or

vision, nor acute or pre-existing mental health

conditions. The age of the participants ranged from

19 to 48 years with a mean age of 23.52 ± 5.63 years.

All participants had to sign an informed consent

form and received credit points for their studies as

compensation. At the start of the study, participants

were informed about the whole procedure, including

the course of the game. They were told that they could

earn points for completing the game’s task. However,

this was just a manipulation intended to encourage

participants to persist in solving the task for as long

as possible, as the game has no clear endpoint.

2.2 Game

2.2.1 Software

The game was developed with PsychoPy (version

2021.1.4), a free and open-source application for

creating experiments in behavioral science with the

programming language Python (Peirce et al., 2019).

For this experiment, PsychoPy was installed on a

Windows 10 operating system, which was used for

both development and game execution. The game

was built as a full-screen presentation, with most of it

created via PsychoPy’s integrated Builder interface.

The final game comprised six routines, containing

components such as buttons and text fields, and two

loops, repeating a single or multiple routines. Some

routines also included custom Python code to meet the

game’s specific requirements, e.g., measuring GD.

2.2.2 Course of the Game

The game consists of three phases: the introduction

(1), the game (2), and the ending (3). Phase 2 can be

further divided into two subphases: the collection task

(2a) and the follow-up questions (2b). The goal of the

game is to collect as many sextuples of cards as

possible, with no indication of the game’s duration or

number of rounds.

Phase 1 masks the start of the game. Here, the

game’s task and instructions (e.g., how to proceed or

collect a card) are presented. This phase was

implemented using three sequentially executed

routines displaying the instructions via text fields.

Participants could spend as much time as needed to

read these instructions, as each routine concludes

only upon pressing the space bar.

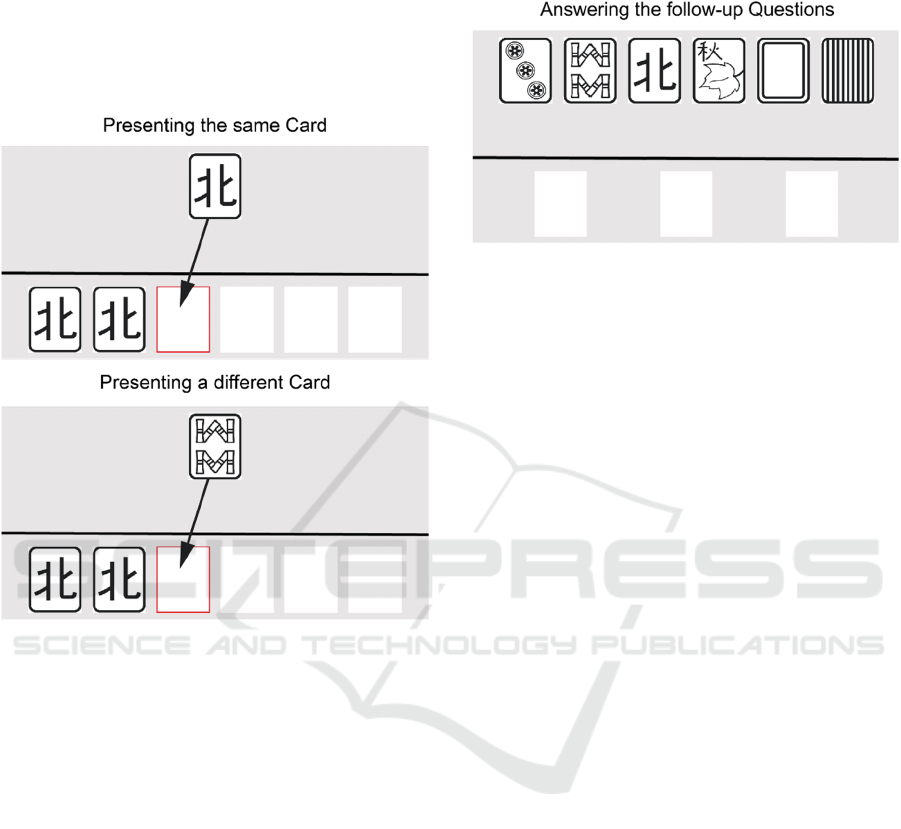

Following the introduction, Phase 2 begins

(specifically Phase 2a), during which participants

attempt to collect a sextuple of cards. This phase was

implemented using a single routine repeated 32 times

by a loop. The routine normally presents one of six

different cards, distinguished by symbols from the

board game Mahjong (i.e., bamboo, coins, leaf

(autumn), striped (reverse side), white (dragon), and

writing (north wind)). The card to be presented is

specified in a file in a fixed order and the participant

must decide for or against the given card. If a

participant decides to collect the card, it must be

moved into the empty field highlighted in the row

below. The next card is then presented upon pressing

the space bar. Alternatively, the participant can also

skip the card. In this case, the space bar must be

pressed without placing a card. This collection

process continues until a sextuple of cards is collected

Assessing Goal Disengagement Using a Digital, Card-Based Game: A Proof of Concept Study

699

or the 32

nd

repetition is completed. A part of this

procedure is presented in Figure 1. However, if a

participant disengages from the previously set goal by

placing a different card, all already placed cards are

removed and the collection process begins with the

newly chosen card. Such event is interpreted as GD

and is registered without the participant noticing.

Figure 1: Example of the collection process in Phase 2a,

highlighting the target field for card placement. On top,

placing the card would initiate the next routine with three

collected cards. On bottom, placing the card would initiate

the next routine with only the newly chosen card.

Each instance of Phase 2a is followed by Phase

2b, which also consists of a single routine. Here,

participants were asked three questions: “Which card

was the last one?”, “Which card was the most

frequent one?”, and “Which card will be the next

one?”. While the first two questions address short-

term memory, the third question requires participants

to make a prediction about the future. To answer the

questions, all six cards and three empty fields are

presented, as illustrated in Figure 2. As before,

participants must move a card into a field and end the

routine by pressing the space bar.

Using a second loop, Phase 2 is repeated between

six and 300 times. Beginning with the 6

th

repetition,

the loop terminates at the end of Phase 2b if at least

one GD was registered. During each repetition, Phase

2b remains unchanged, whereas Phase 2a changes

accordingly. The game is programmed such that the

task can only be solved in the 1

st

and 5

th

repetition,

because the 6

th

card of a sextuple cannot be found in

the other repetitions.

Figure 2: Illustration of Phase 2b, showing three empty

fields for answers. For clarity, the mapping of questions to

answer field has been omitted.

The final phase, Phase 3, has only the purpose of

signalizing the end of the game. Therefore, a single

routine displaying the message via a text field

sufficed. Pressing the space bar in this phase closes

the game completely.

2.2.3 Output Parameters

The game exports all parameters that PsychoPy’s

experiments provide by default. Additionally, there is

three numeric, self-implemented parameters: GD

count, collected cards, and repetitions. All three are

initialized with the value zero.

GD count is the number of GDs a participant

made during the game. The value is incremented by

one whenever a GD occurs, i.e., if a participant

disengages from collecting the chosen sextuple of

cards.

Collected cards is the number of cards collected

by a participant by the time a GD occurs. Since there

could be several GDs, this parameter represents the

mean. In case of the example in Figure 1 (bottom), the

value would be 2 if no other GD occurs.

Repetitions is the duration by the time a GD

occurs. As with the collected cards, it represents the

mean. A characteristic of this parameter is that its

value is only incremented by one during the

initialization of the routine from phase (2a) if the first

card was already collected. Otherwise, the value

remains at zero.

2.3 Statistical Analysis

The analysis of the output parameters was conducted

using the programming language R (version 4.4.1).

Next to some basic functions, the investigation of

parameters’ primary characteristics required

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

700

functions of the ggplot2 package. To visualize the

correlations between parameters in a 3-dimensional

space, the scatterplot3d package that is built for

multivariate data (Ligges & Maechler, 2003) was

employed.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Key Results

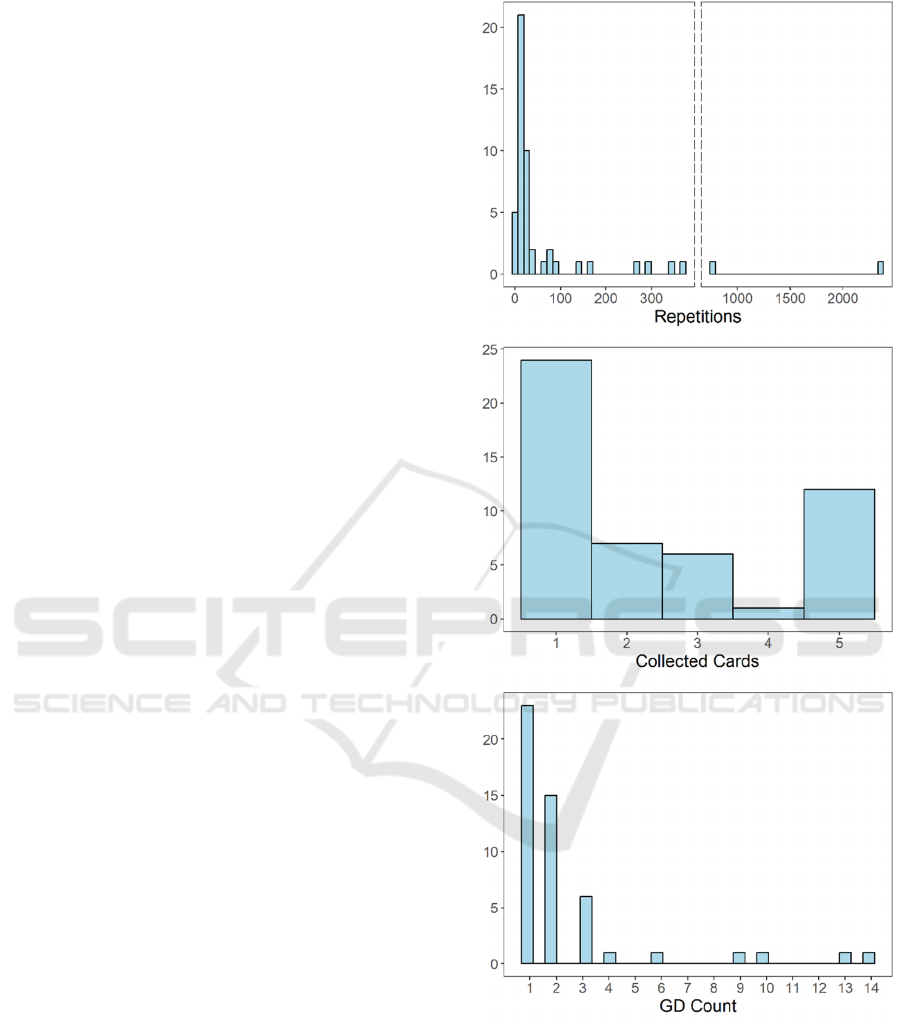

The frequency distributions of the three outcome

parameters in the form of histograms are illustrated in

Figure 3. The top histogram indicates that most of the

GDs occurred mainly within 100 repetitions. Other

than that, there were only a few participants that

disengage later, resulting in a mean of

113.57 ± 353.77 repetitions. One participant was

particularly persistent in reaching the goal. It was not

until the 2378 repetition that this participant changed

to a different card.

The middle histogram of Figure 3 clearly shows

that when participants disengaged from the goal, they

did so preferably after the 1

st

or after the 5

th

collected

card. Only one participant changed after collecting

the 4

th

card. As a result, the participants collected

2.45 ± 2.9 cards on average.

When examining the bottom histogram of

Figure 3, it is noticeable that there are similarities

with the frequency distribution of the top histogram.

On the one hand, the number of GDs a participant

made tends to be in the lower spectrum. On the other

hand, only a minority of participants disengaged more

than five times, with one participant having 14 GDs

forming the end of the spectrum. On average,

participants made 2.54 ± 2.9 GDs during the game.

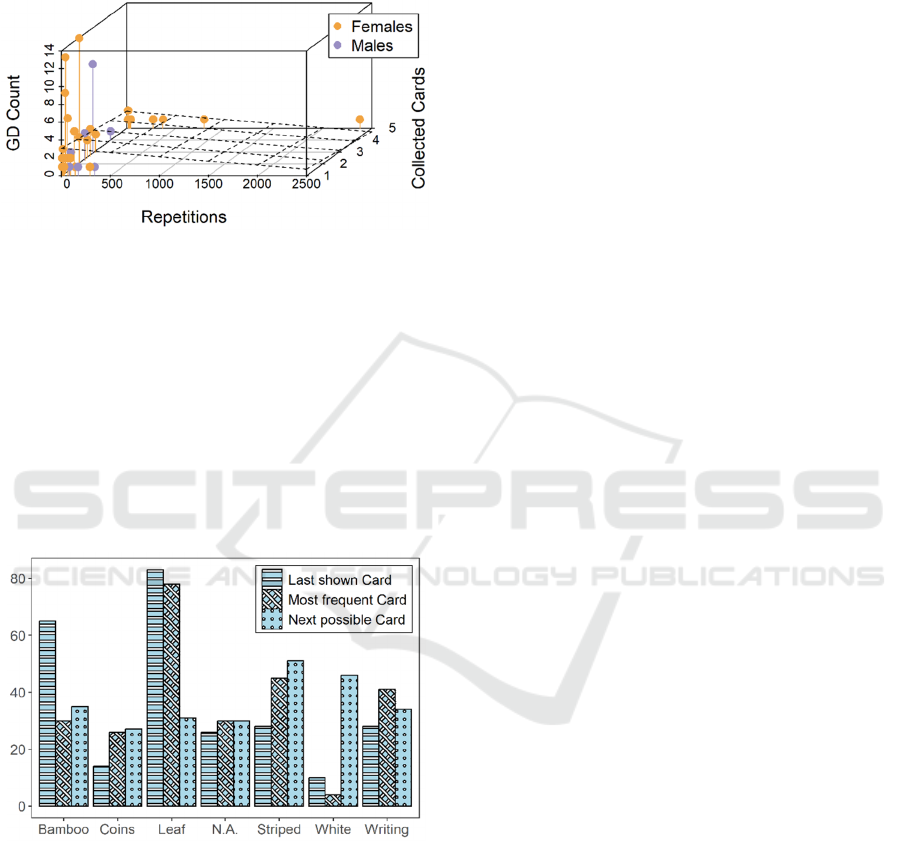

The correlations between the parameters are

presented in Figure 4, with no obvious differences

observed between females and males. When viewed

together, it appears that two clusters have formed in

the lower spectrum of GD count: a larger cluster in

relation to a few collected cards (up to three) and a

smaller cluster in relation to many collected cards

(more than three).

The regression plane provides further information

about the relationships between parameters. Based on

the assumption that GD count is the predictor, the

plane is a visual representation of the formula:

0a∗xb∗

y

c∗zd (1)

The regression plane has an intercept of 3.35.

There is a slight negative slope of ~ -0.001 along the

x-axis and a slight negative slope of -0.29 along the

y-axis, suggesting that participants who adhered their

Figure 3: Histograms showing the frequency of output

parameters across the curse of the game. The top one shows

the repetitions until a GD occurred, the middle one the

collected cards until a GD occurred, and the bottom one the

number of GDs made during the game.

goals were slightly more willing to perform more

repetitions and tended to collect more cards than

those who disengaged more frequently. However, the

correlations are not significant (F(2, 47) = 1.21,

Assessing Goal Disengagement Using a Digital, Card-Based Game: A Proof of Concept Study

701

p = 0.31). This also becomes clear when looking at

Figure 4. The slope along the x-axis is only visible

due to the broad spectrum covered by the parameter

and the slope along the y-axis, even it is greater than

the other one, is barely recognizable.

Figure 4: 3-Dimensional point cloud showing the

relationships between repetitions (x-axis), collected cards

(y-axis), and GD count (z-axis). For reference, a regression

plane (dotted grid) is provided.

3.2 Secondary Results

The entire game, including the loading time of

PsychoPy, took 9.73 ± 10.12 minutes on average. The

fastest participant finished in 5.27 minutes, whereas

the slowest participant, which was also the one with

the most repetitions, took 1 hour and 14.55 minutes

(74.55 minutes).

Figure 5: Histogram of responses to the follow-up

questions. Since participants were allowed to skip the

questions, a category for no answer (N.A.) is included.

When answering the follow-up questions about

the last shown card and the most frequently occurring

card, participants predominantly chose the card with

the leaf symbol, as presented in Figure 5. Especially

for the latter question, this card was chosen much

more frequently than any other card. When asked

which card would be shown next, the participants'

responses varied considerably. Instead of having a

preference, they choose each card almost equally

often, except for the card with the coins, which was

chosen far less frequently.

4 DISCUSSION

The results indicate that the participants generally

exhibited homogeneous behavior in terms of both

solving the game’s task and answering the follow-up

questions. In particular, no significant differences

were found in behavior when solving the game's task.

The two main clusters in the lower spectrum of GD

count and the slopes of the regression plane could still

reveal some interesting behavioral patterns. It appears

that there are slight tendencies among the participants

who adhered to their goals more persistently and the

participants who disengaged more quickly and more

frequently. Perhaps, participants who disengaged

before collecting the 4

th

card needed a short

orientation phase, while participants who collected

more than three cards approached the task in a

systematic and profit-oriented manner. Overall, the

adaptive value of GD under the circumstance that the

goal is unattainable (Tomasik et al., 2010; Wrosch et

al., 2003) appears to have been recognized either

intuitively or intentionally. Only one participant

demonstrated enormous persistence toward achieving

the goal, which might have caused a similarly

negative effect as a goal conflict, as the hope of

achieving the goal could still have existed (Freund

and Tomasik, 2021).

In the follow-up questions, it is particularly

noticeable that the answers to the two questions on

short-term memory were similar in the sense that the

participants preferred to select a specific card. In

contrast, there was no clear preference for the

question on predicting the future, which in turn could

reflect the group's individualism.

Regarding similar games, homogeneous behavior

within homogeneous groups is to be expected. An

example is the Iowa Gambling Task, a card-based

game for decision-making (Bechara et al., 1994). An

investigation of this game by Steingroever et al.

(2013), testing the performance of a homogeneous

group of healthy participants, demonstrated that

although the participants showed individual behavior,

they also shared a common characteristic: taking

smaller risks during the course of the game. A study

on another game for decision-making (Franckenstein

et al., 2022) could also supports the feasibility of the

novel assessment method presented here. In that

study, a homogeneous group (students and staff from

the same university) was first divided into two

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

702

subgroups by manipulating the task. Thus, the

common characteristic that the control group was

more likely to use a safe strategy could be observed.

In technical respect, the implementation of the

game via PsychoPy (Peirce et al., 2019) was quick

and smooth. Except for a few features, the integrated

Builder interface was sufficient for the

implementation, so that the game could be rebuilt

with little prior knowledge. The game’s simplicity

makes it even realistic to build the game with other

applications or programming languages, which

should increase its acceptance.

Despite all the positive aspects, some limitations

must be mentioned. First, the number of participants

was far too small to provide conclusive findings with

this study. And second, the game requires testing on

a heterogeneous group. While clearer generalizability

can be achieved with a homogeneous group compared

to a heterogeneous group, the results cannot be

generalized to the entire population (Jager et al.,

2017). Additionally, the group consists of psychology

students who may have been aware of the concept of

GD and thus may have influenced the results. A

heterogeneous group is therefore needed to capture

sufficient characteristic differences that may be

helpful in a clinical setting, e.g., for the diagnosis of

conditions such as pathological gambling or for the

selection of rehabilitation and behavioral therapies.

While in the diagnosis of gambling, high repetitions

and a low GD count may indicate risky gambling

behavior, in the selection of rehabilitation and

behavioral therapy, these same values could represent

an individual’s persistence, suggesting the suitability

of long-term therapies.

Altogether, future research should focus on an

external validation of this game to strengthen the

results of this study. The Risk Tolerance

Questionnaire, the Arnett Inventory of Sensation

Seeking, or the Sensation Seeking Scale, with which

pathological gamblers achieve demonstrably high

values (Powell et al., 1999), seem quite useful for this

purpose in the form of a linear regression analysis,

with one of these questionnaires as the predictor.

Alternatively, this game could be compared to similar

behavioral, gambling-related methods, for example,

to the long-established Iowa Gambling Task (Bechara

et al., 1994) or the recently published dice-based

game for decision-making (Franckenstein et al.,

2022). Such comparisons may help to identify the

differences and similarities, allowing for more

efficient application of these games and a better

understanding of how they capture various aspects of

decision-making and GD.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This proof of concept study aimed to evaluate the

feasibility of a digital game for GD based on

collecting a sextuple of cards. The results revealed

that the behavior of the participants with regard to GD

is comparatively similar. Only in the number of

repetitions and the number of collected cards,

participants seem to have had some different, albeit

minor, tendencies at the time of a GD. In addition,

there was no preference in response to the question

about predicting the future, which in turn could reflect

the group's individualism.

Due to its simplicity, the game is not only easy to

replicate, but also easy to understand in its

application. In addition, it is unaffected by external

influences and could therefore serve as an alternative

assessment method to previous ones, such as those

relying on solving a puzzle (Thomsen et al., 2017) or

becoming a member of a group (Rühs et al., 2022).

However, it is recommended to investigate the

assessment method in further studies with a more

heterogeneous group or external validation using

methods such as questionnaires or similar games. The

final version of this game should provide a scoring

system that uses GD to rate patient behavior. Such a

score could help predict the potential success of long-

term rehabilitation and behavioral therapies that

depend on individual’s persistence, such as therapies

for Parkinson's disease (Pellecchia et al., 2004) or

after a stroke (Dam et al., 1993).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We extend our gratitude to Martin J. Tomasik

(Institute of Education, University of Zurich) for his

advice on the development of the game and on an

earlier draft of this paper.

REFERENCES

Baldo, J. V., Paulraj, S. R., Curran, B. C., & Dronkers, N.

F. (2015). Impaired reasoning and problem-solving in

individuals with language impairment due to aphasia or

language delay. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1523.

Bechara, A., Damasio, A. R., Damasio, H., & Anderson, S.

W. (1994). Insensitivity to future consequences

following damage to human prefrontal cortex.

Cognition, 50(1-3), 7-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-

0277(94)90018-3

Dam, M., Tonin, P., Casson, S., Ermani, M., Pizzolato, G.,

Iaia, V., & Battistin, L. (1993). The effects of long-term

Assessing Goal Disengagement Using a Digital, Card-Based Game: A Proof of Concept Study

703

rehabilitation therapy on poststroke hemiplegic

patients. Stroke, 24(8), 1186-1191. https://doi.org/10.

1161/01.STR.24.8.1186

DiCerbo, K. E. (2014). Game-based assessment of

persistence. Journal of Educational Technology &

Society, 17(1), 17-28.

Franckenstein, S., Appelbaum, S., & Ostermann, T. (2022).

Implementation and Feasibility Analysis of a

Javascript-based Gambling Tool Device for Online

Decision Making Task under Risk in Psychological and

Health Services Research. In Proceedings of the 15th

International Joint Conference on Biomedical

Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC

2022) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF (pp. 469-474).

https://doi.org/10.5220/0010826700003123

Freund, A. M., & Tomasik, M. J. (2021). Managing

conflicting goals through prioritization? The role of

age and relative goal importance. Plos one,

16(2), e0247047. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.

0247047

Haase, C. M., Heckhausen, J., & Wrosch, C. (2013).

Developmental regulation across the life span: toward a

new synthesis. Developmental Psychology, 49(5), 964-

972. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029231

Heckhausen, J., Wrosch, C., & Schulz, R. (2010). A

motivational theory of life-span development.

Psychological Review, 117(1), 32-60. https://doi.

org/10.1037/a0017668

Jager, J., Putnick, D. L., & Bornstein, M. H. (2017). II.

More than just convenient: The scientific merits of

homogeneous convenience samples. Monographs of

the Society for Research in Child Development, 82(2),

13-30. https://doi.org/10.1111/mono.12296

Kappes, C., & Schattke, K. (2022). You have to let go

sometimes: Advances in understanding goal

disengagement. Motivation and Emotion, 46(6), 735-

751. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-022-09980-z

Ligges, U., Maechler, M. (2003). Scatterplot3d - An R

Package for Visualizing Multivariate Data. Journal of

Statistical Software, 8(11), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.

18637/jss.v008.i11

Morris, R. G., Rushe, T., Woodruffe, P. W. R., & Murray,

R. M. (1995). Problem solving in schizophrenia: a

specific deficit in planning ability. Schizophrenia

research, 14(3), 235-246.

Pellecchia, M. T., Grasso, A., Biancardi, L. G., Squillante,

M., Bonavita, V., & Barone, P. (2004). Physical therapy

in Parkinson’s disease: an open long-term rehabilitation

trial. Journal of Neurology, 251, 595-598.

Peirce, J., Gray, J. R., Simpson, S., MacAskill, M.,

Höchenberger, R., Sogo, H., Kastman, E., & Lindeløv,

J. K. (2019). PsychoPy2: Experiments in behavior

made easy. Behavior Research Methods, 51, 195-203.

https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-018-01193-y

Powell, J., Hardoon, K., Derevensky, J. L., & Gupta, R.

(1999). Gambling and Risk-Taking Behavior among

University Students. Substance Use & Misuse, 34(8),

1167-1184. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826089909039402

Rühs, F., Greve, W., & Kappes, C. (2022). Inducing and

blocking the goal to belong in an experimental setting:

Goal disengagement research using Cyberball.

Motivation and Emotion, 46(6), 806-824.

Steingroever, H., Wetzels, R., Horstmann, A., Neumann, J.,

& Wagenmakers, E. J. (2013). Performance of healthy

participants on the Iowa Gambling Task. Psychological

Assessment, 25(1), 180-193. https://doi.org/10.

1037/a0029929

Thomsen, T., Kappes, C., Schwerdt, L., Sander, J., &

Poller, C. (2017). Modelling goal adjustment in social

relationships: Two experimental studies with children

and adults. British Journal of Developmental

Psychology, 35(2), 267-287. https://doi.org/10.

1111/bjdp.12162

Tomasik, M. J., Silbereisen, R. K., & Heckhausen, J. (2010).

Is it adaptive to disengage from demands of social

change? Adjustment to developmental barriers in

opportunity-deprived regions. Motivation and Emotion,

34, 384-398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-010-9177-6

Wrosch, C., Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Schulz, R.

(2003). The importance of goal disengagement in

adaptive self-regulation: When giving up is beneficial.

Self and Identity, 2(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.

1080/15298860309021.

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

704