Electroencephalograph Based Emotion Estimation

Using Multidimensional Directed Coherence and Neural Networks

Under Noise

Haruka Torii

1,2 a

, Takamasa Shimada

3

, Osamu Sakata

4

and Tadanori Fukami

5

1

Tokyo Denki University, 5, Senjuasahi-cho, Adachi-ku, Tokyo, 120-0026 Japan

2

Oki Electric Industry Co., Ltd. 1-16-8, Chuo, Warabi-shi, Saitama, 335-8510 Japan

3

Tokyo Denki University, 5, Senjuasahi-cho, Adachi-ku, Tokyo, 120-0026 Japan

4

Tokyo University of Science 6-3-1 Niijuku, Katsushika-ku, Tokyo 125-8585 Japan

5

Yamagata University, 4-3-16 Jonan, Yonezawa-shi, Yamagata, 992-8510 Japan

Keywords: Emotion Estimation, Electroencephalography (EEG), Multidimensional Directed Coherence, Neural Network

(NN), White Noise, Pink Noise.

Abstract: In recent years, research focused on emotion based on brain activity has yielded significant insights into the

mechanisms of information processing in the brain. Leveraging this knowledge, studies have increasingly

examined the effects of various stimuli on human emotions, with applications progressing in fields such as

neuromarketing. However, existing methods for emotion estimation from EEG—such as those using power

spectra, correlations, or deep learning—face challenges in generalizability due to considerable individual

differences. In this study, we applied multidimensional directed coherence analysis, which can analyze the

flow of information in the brain, to the measured EEG data. Following this, we trained a neural network using

data augmented with noise to simulate individual differences, proposing a method capable of generalizable

emotion inference. As a result, we achieved an average accuracy rate of 99.91% on training data and 90.83%

on test data.

1 INTRODUCTION

Emotion plays a crucial role in human decision-

making and social behavior, drawing increasing

attention to the relationship between emotion and the

brain, particularly in neuroengineering. This topic is

considered highly significant, as understanding the

connection between emotion and brain activity is

expected to yield applications in fields such as brain-

computer interfaces (BCI) and neuromarketing.

The relationship between brain activity and

emotion has been explored extensively through fMRI

studies. For example, Papez et al. examined the link

between human emotions and hippocampal activity

(Papez, 1937). Irwin conducted functional magnetic

resonance imaging (fMRI) studies and documented

amygdala activation at both poles in response to

specific stimuli (Irwin et al., 1996). George used

positron emission tomography (PET) on individuals

experiencing sadness and happiness (George et al.,

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-6668-6075

1995). Findings indicated marked activation in the

limbic system and brainstem during sadness, while no

similar increase in brain activity was found during

happiness. Fisher identified the activation of the

amygdala and hippocampus when subjects viewed

faces depicting fear. These studies highlight the

association between certain brain regions and specific

emotions (Fischer et al., 2003). Another study

assessed brain activity across various emotional states

in response to diverse facial and background images

(Shimada et al., 2009). However, due to the high cost

of fMRI, it is challenging to apply it extensively in

emotion-related brain activity studies across various

fields.

Therefore, electroencephalography (EEG) is

widely used as a more economical approach for brain

activity measurement, particularly in areas such as

psychiatry. EEG thus offers significant advantages

for studying brain activity related to a range of

emotions.

Torii, H., Shimada, T., Sakata, O. and Fukami, T.

Electroencephalograph Based Emotion Estimation Using Multidimensional Directed Coherence and Neural Networks Under Noise.

DOI: 10.5220/0013256000003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 1, pages 647-654

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

647

If emotions can be estimated from brain waves,

this could lead to applications in neuromarketing,

such as product development based on consumers'

unconscious reactions, as well as in safe driving

assistance systems that monitor drivers' emotional

states to help prevent dangerous driving.

Although several studies have reported emotion

classification using EEG, many of them focused on

only 2 to 3 specific emotions (Alarcão & Fonseca,

2019). However, Plutchik previously reported that

human emotions can be expressed through a

combination of 8 basic emotions (Plutchik et al.,

1980). Thus, existing research using brainwave-based

emotion classification has not fully covered this

diverse range of emotions. This study aims to classify

four types of emotional states based on Plutchik's

eight basic emotions.

2 RELATED WORK

There are several challenges in using EEG for

emotion estimation. These include the fact that EEG

is a time-series signal with extensive information,

exhibits significant inter-individual variability, and

lacks clear patterns associated with specific

emotional states. Previous studies have attempted to

capture and classify emotional characteristics in EEG

through signal processing techniques. Common

approaches have relied on power spectral analysis and

electrode correlation information. More recently,

machine learning-based methods have been explored

to automatically extract previously unknown

emotion-related features from EEG signals.

Zheng proposed a method to estimate three

emotional states—positive, negative, and neutral—

using the GSCCA method, which identifies

correlations between electrodes and EEG frequencies

(Zheng, 2017). Li et al. proposed an estimation

method for quantifying happiness and sadness using

CSP and LinearSVM (Li & and Lu, 2009). In their

study, participants were shown facial images

representing specific emotions, and their EEG was

recorded. Emotion estimation with this classifier

achieved an average test accuracy of 93.5%. Saha

reports a method using CNN for emotion estimation

(Saha et al., 2022). However, because DNN-based

emotion estimation algorithms function as black

boxes, they cannot reliably estimate emotion based on

brain activity features identified in EEG and fMRI

studies. This limitation reduces the reliability of

EEG-based emotion estimation.

This study aims to analyze the relationship

between emotion and brain activity using EEG by

combining a signal processing method that visualizes

the correlation and direction of each frequency

between electrodes with a neural network (NN). In a

previous study, we proposed two method using

multidimensional directed coherence analysis to

visualize brain activity from EEG signals (Torii et al.,

2023; Torii et al., 2024). Multidimensional directed

coherence analysis tracks brain activity more

effectively than one-dimensional coherence and was

used to estimate joy, sadness, anger, and surprise.

With the exception of joy, multidimensional

coherence analysis achieved significantly higher

accuracy than one-dimensional coherence analysis,

which does not capture the multidimensional flow of

brain activity.

We extracted frequency and electrode

combinations that showed statistically significant

differences in the small/large relationship of

multidimensional directed coherence values across

emotions. These differences were used as rules for

emotion estimation, termed 'relative emotion rules,' as

detailed in Section 3.2. In the first method, each

extracted relative emotion rule was assigned equal

weight for emotion estimation. However, there are

varying levels of importance among these rules in

accurately estimating emotion.

We then explored a method to enhance accuracy

by focusing on relative emotion rules that are highly

effective for emotion estimation in the second

method. NNs are widely used in various fields to

provide optimal solutions by weighting data

appropriately. Previous research describes a method

for classifying the importance of relative emotion

rules across four emotions—joy, sadness, anger, and

surprise—using NNs.

This study also explored methods to classify four

emotional states—joy, sadness, anger, and surprise—

by combining multidimensional directed coherence

analysis, noise, and NNs. By incorporating noise, we

aimed to represent individual variability in EEG

signals, and by utilizing all values obtained from the

analysis—not just those used in the relative emotion

rule—we sought to extract features that, while not

statistically different, play a crucial role in accurate

emotion estimation.

The contributions of this study are as follows.

First, by combining multidimensional directed

coherence analysis with NNs, we achieved a higher

accuracy rate than previous methods in the test data.

Second, by analyzing the NN weights, we

demonstrated the potential to identify not only areas

with significant differences between emotions but

also subtle features that are important for emotion

classification. This approach, which leverages cost-

BIOINFORMATICS 2025 - 16th International Conference on Bioinformatics Models, Methods and Algorithms

648

effective and widely accessible EEG devices to

enable broader emotion classification, holds potential

for applications in diverse fields such as

neuromarketing, driver assistance, and robotic

collaboration through emotion state inference.

3 PROPOSED METHOD

We have previously reported on methods for

estimating emotion using EEG with

multidimensional directed coherence. In the initial

study, we applied multidimensional directed

coherence analysis to EEG data representing specific

emotional states, extracting statistically distinct

features for each frequency and electrode

combination. These features were termed 'relative

emotion rules, and unknown emotional states were

identified by comparing them with these rules and

employing a majority voting principle.

In the subsequent research, we suggested a

method for evaluating the importance of relative

emotion rules by applying weighting based on a NN,

rather than treating all rules as equal.

In this paper proposes an inference method that

directly applies a NN to the values obtained from

multidimensional directed coherence analysis

without using relative emotion rules. By

incorporating noise to represent individual variability,

we achieved high accuracy.

3.1 Multidimensional Directed

Coherence

First, multidimensional directed coherence analysis is

described (Sakata et al., 1998). Studies using fMRI on

emotion have reported that activity in specific regions

of the brain is associated with specific emotions

(Fischer et al., 2003). Therefore, in this study, a

multidimensional directed coherence analysis was

conducted to visualize information flow, as

considering the source of EEG signals is essential for

accurate emotion estimation. Other analytical

methods do not consider for information flow.

The coherence analysis method in signal

processing explains the level of coherence between

two time-series signals x(t) and y(t) (whether they are

in phase or correlated). Furthermore, the directed

coherence analysis method can be used to determine

the direction of coherence.

Multidimensional directed coherence analysis is

an extension of directed coherence analysis.

Multidimensional directed coherence analysis

estimates the direction of signal propagation at a

specific frequency between electrodes, assuming both

immediate, delay-free signals from sources near the

electrode where the EEG is measured and delayed,

attenuated signals from sources near other electrodes.

Directed coherence analysis, which takes into account

only signal propagation between two electrodes, can

incorrectly indicate apparent signal flow, such as a 10

Hz flow between electrodes x

and x

, as illustrated

in

Figure 1

(Kamitake et al., 1982). In contrast,

multidimensional directed coherence analysis can

eliminate this apparent signal flow by using phase

information across all electrodes and accounting for

the temporal relationship between them.

Figure 1: Instances of misinterpretation that may arise when

employing directed coherence analysis.

The formula for multidimensional directed

coherence analysis was derived in a previous study

(Sakata et al., 1998). Multidimensional directed

coherence analysis can not only detect the coherency

components that conventional coherence analysis

could detect, but also the temporal backward/forward

relationship among them. This relationship is

interpreted as information flow. Multidimensional

directed coherence is calculated with

multidimensional autoregressive (AR) model

estimation. An AR model regresses the current values

using historical data. Assume that the EEG time series

𝑥

𝑛 is represented by an AR model in Equation (1).

Here, 𝛼 is the AR coefficient, 𝛽 is the disturbance,

and 𝑀 is the AR order.

𝑥

𝛼

𝑥

𝛽𝜔

(1)

Let 𝐴

and 𝑏

be the AR coefficients for the

signal between electrodes 𝑖 and 𝑗 obtained by Fourier

transforming both sides of equation (1) and predictive

residual, respectively. Let the number of electrodes

for measuring EEG be k, frequency be f, white noise

with zero means and one variance be 𝜔

, power

spectrum at electrode 𝑖 be 𝑃

𝑓

, and cross-spectrum

between signals obtained from electrodes 𝑖 and 𝑗 be

𝑃

𝑓

. In this study, γ

𝑓 is the multidimensional

directed cross-spectrum and is defined in equation

(2). Furthermore, the multidimensional directed

Electroencephalograph Based Emotion Estimation Using Multidimensional Directed Coherence and Neural Networks Under Noise

649

coherence between measurement electrodes i and j

can be expressed as γ

𝑓

, where the direction of

information flow indicated by the multidimensional

directed coherence is 𝑥

→𝑥

.

𝛾

𝑓

𝑃

𝑓

𝑃

𝑓

⋅𝑃

A

𝑓

⋅𝑏

𝑃

𝑓

𝑖,

𝑗

1,2,⋅⋅⋅ ,𝑘

(2)

3.2 Relative Emotion Rules

For the selected EEG, the multidimensional directed

coherence analysis described in 3.1 was applied to

obtain the correlation and direction of information

flow (information flow in the brain) for each

combination of electrodes and each frequency.

Figure

2

displays the shape of analyzed data. The vertical

axis represents a combination of electrodes, and the

horizontal axis represents frequencies from 0 to 40.48

Hz. The number of subjects is represented in the

depth direction. Analysis data is obtained for all

subjects and each emotion. These data were divided

into training data to create an emotion estimation

algorithm and test data to verify the accuracy of

emotion estimation.

In the context of two emotions, if Welch’s t-test

at a significance level of 5% reveals a significant

difference in the mean values of multidimensional

directed coherence for each emotion at a certain

frequency for a specific combination of electrodes,

then a significant difference can occur in the amount

of information flow within the brain between the two

emotions for that electrode combination and

frequency.

We used this difference in significant information

flow between emotions (relative emotion rule) for

estimating emotions. All emotion combinations,

electrode combinations, and frequency patterns were

examined to obtain relative emotion rules.

3.3 Proposed Method

This section explains the conventional emotion

estimation method based on the relative emotion rules

established in Section 3.2, and compares it with the

proposed method, which does not rely on relative

emotion rules.

First, we describe the conventional method. Using

the EEG of a specific emotion in the training data, we

obtained the distribution of values of multi-

Figure 2: Shape of analyzed data using multidimensional

directed coherence.

dimensional directed coherence for a specific

combination of electrodes at a specific frequency,

which was approximated by a normal distribution.

Next, when estimating the emotion, the normal

distribution was compared with the test data for

which the emotion was unknown. When the value

obtained by integrating the probability density

function of the normal distribution from ∞ to the

value of multidimensional directed coherence of the

test data was larger than a predetermined smaller

percentage (discrimination threshold), the value is

determined to be considerably larger than the

distribution of directed coherence values of the

specific emotion. By, contrast, when the value

obtained by integrating the probability density

function of the normal distribution from -∞ to the

value of multidimensional directed coherence of the

test data was smaller than the discrimination

threshold, the value is determined to be considerably

smaller than the distribution of directed coherence

values of the specific emotion.

Based on the large/small relationship with the

specific emotion of the obtained training data, a

relative emotion rule was extracted for which this

large/small relationship was consistent. The relative

emotion rule indicates the large/small relationship of

values between two emotions, one of which was set

to a specific emotion of the training data such that the

other emotion can be inferred to be the emotion of the

test data. This procedure was performed for all

electrode combinations and frequencies, and the

emotion of the test data inferred from all extracted

relative emotion rules was used to determine the most

plausible emotion based on the principle of majority

rule voting, resulting in the final emotion estimation.

Figure 3 displays the flow of emotion estimation as

“Previous Method 1”.

The second method is shown as "Previous Method

2" in Figure 3. This method based on the large/small

relationship obtained by comparing testing data and

discrimination threshold, 1 was set when this

large/small relationship matched the relative emotion

BIOINFORMATICS 2025 - 16th International Conference on Bioinformatics Models, Methods and Algorithms

650

Figure 3: Estimation process of the two preceding methods and the proposed method.

rule and 0 when this condition was not satisfied.These

results were used as input data to estimate the

emotions using a NN. Using an NN, the rules are not

treated in the same rank when estimating each

emotion. However, the values are adjusted using the

weight coefficients. Larger coefficients can be

applied to rules that are more important for estimating

emotion, and smaller coefficients can be applied to

less important rules, allowing estimation to be

performed with sorting of rules.

The proposed method is shown in Figure 3 as

"Proposed Method". Two types of data are prepared:

data obtained after multidimensional directed

coherence analysis and data with added noise post-

analysis. These two datasets are shuffled and divided

into training and test data. Next, the two-dimensional

post-analysis data are converted into one-dimensional

data, and all values obtained from the analysis are

used as input data for the NN.

The NNs used in both the previous method 2 and

the proposed method were simple, consisting of only

two layers: an input layer and an output layer. We

used stochastic gradient descent (SGD) as the

optimizer, Softmax as the activation function, and

CrossEntropyLoss as the loss function. We stopped

the training when the loss stopped decreasing to avoid

overfitting.

4 EXPERIMENTS

The proposed method in this paper aims to evaluate a

broader range of emotions based on Plutchik's basic

emotions. Publicly available datasets did not include

emotions comparable to those targeted by this

method; therefore, specific emotional states were

generated using images based on techniques from

previous studies. (Torii, 2023).

Informed consent was obtained from the

participants regarding the purpose of the experiment

and the risks associated with participation in the

experiment by procedures approved by the Bioethics

Committee for Human Life at Tokyo Denki

University. Furthermore, their written consent was

obtained for participation.

EEG measurements were performed within 1 min

of image presentation. The electrode arrangement

was based on the international 10–20 method, and the

unipolar derivation method was used with the average

of the two earlobe electrodes as the reference

electrode. The measured data were digitized and

recorded at a sampling frequency of 200 Hz. The

measured EEG data were pre-processed using a high-

pass filter with a cutoff frequency of 0.5 Hz, and a

low-pass filter with a cutoff frequency of 60 Hz. EEG

data was measured at Fp1, Fp2, F3, F4, P3, P4, T3,

T4, O1, and O2 using the average potential of

earlobes A1 and A2 as a reference. During the

measurements, the participants were instructed to

minimize body movements and blinking. However, if

a significant artifact was detected, the measurements

were repeated. The subjects included 30 healthy

individuals, comprising 23 males and 7 females, with

an average age of 21.9 years (±1.57).

EEG data from the subsequent 20 s (from the 40th

to the 60th second) of the 1 min of the measured data

were used as EEG data.

In the analysis, 8096 frequencies, from 0 to 40.48

Hz at 0.005 Hz intervals were used. Two electrodes

were selected from 10 electrodes. Then, a total of 90

combinations of electrodes were evaluated.

Electroencephalograph Based Emotion Estimation Using Multidimensional Directed Coherence and Neural Networks Under Noise

651

To validate the proposed method, we compared

emotion estimation using relative emotion rules with

a method that generates relative emotion rules

through coherence analysis, which visualizes the

actual correlations between electrodes, rather than

using multidimensional directed coherence analysis.

The data used to create the relative emotion rules

and train the NN were designated as training data, and

the data that were not used were designated as test

data.

5 RESULTS

The dataset for training the neural networks (NNs)

was split into training (90%) and test (10%) sets,

using 10-fold cross-validation. Emotion estimation

was performed on both sets in each fold, and the

average accuracy was computed over 10 folds.

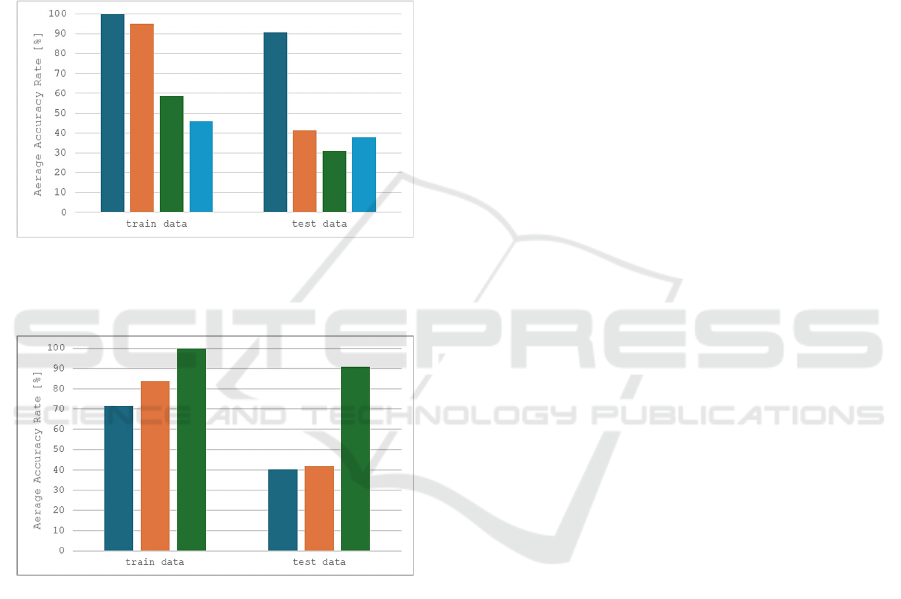

Figure

4

shows results of NN training and inference using

noiseless data from multidimensional directed

coherence analysis of EEG signals, as well as results

when combining this data with noise-augmented data.

White noise (mean: 0, variance: 1) was used as the

noise source. Training with only noiseless data

achieved average accuracies of 75.68% (±10.16) for

training and 28.33% (±10.67) for test sets. When

noiseless data was combined with noise-augmented

data, accuracies improved to 99.82% (±0.41) for

training and 71.67% (±5.20) for test sets, showing

noise addition enhances test accuracy.

Subsequently, different types of noise were

introduced to examine their effects on training and

inference performance. Unlike white noise, which has

a uniform power spectrum across all frequencies,

pink noise has higher power in low-frequency

components, with power spectral density decreasing

as frequency increases. The noise types used are as

follows:

White Noise (mean: 0, variance: 0.1)

White Noise (mean: 0, variance: 0.01)

Pink Noise

Figure 5

shows the results of adding these noise

types to the training data. With white noise (variance

0.1), the average accuracy was 99.49% (±0.73) for

training and 75.42% (±5.09) for test data. For white

noise (variance 0.01), training accuracy increased to

99.73% (±0.46), while test accuracy dropped to

68.33% (±6.77). Pink noise achieved the highest

accuracy rates, with 99.91% (±0.18) for training data

and 90.83% (±4.86) for test data. Among the tested

noise types, pink noise provided the best overall

performance.

Figure 4: Average accuracy rate of the proposed method

with noise and noiseless conditions.

Figure 5: Comparison using pink noise and white noise with

varying levels of variance is presented as follows: Blue:

pink noise, Orange: white noise with a variance of 0.01,

Green: white noise with a variance of 0.1, Cyan: white noise

with a variance of 1.

To confirm whether the proposed method

captures essential features for emotion representation

better than statistically significant relative emotion

rules, we compared several approaches: using only

the relative emotion rule (previous method 1),

combining the rule with NNs (previous method 2),

and coherence-based methods without considering

multidimensional flow.

Figure 6

shows the estimation

results. For the proposed method, we used pink noise,

as it demonstrated the highest accuracy rate.

The average accuracy rates for the previous

method 2 were 95.06% (±2.77) for training and

41.44% (±3.98) for test data, while for previous

method 1, they were 58.51% (±4.86) and 31.07%

(±3.42), respectively. The conventional coherence

analysis method with relative emotion rules yielded

accuracies of 45.95% (±2.81) for training and 37.98%

(±3.42) for test data.

Previous method 2 uses binary values (1 or 0) for

inference, whereas the proposed method incorporates

correlation values from multidimensional directed

coherence analysis. To examine the impact of input

data flexibility, we compared results using only

relative emotion rules with those using correlation

BIOINFORMATICS 2025 - 16th International Conference on Bioinformatics Models, Methods and Algorithms

652

values post-analysis. For matches with the rules, the

correlation values were retained; for mismatches, the

values were set to 0.

Figure 7

shows the results. Using correlation

values for unknown emotions from all electrode

combinations and frequencies in the relative emotion

rules, the average accuracy was 71.31% (±19.13) for

training and 40.12% (±2.25) for test data. When

retaining correlation values for matches with the rules

and setting mismatches to 0, the training accuracy

was 83.57% (±7.78), and the test accuracy was

41.79% (±2.58).

Figure 6: Average accuracy rate: Blue: Proposed method

(pink noise), Orange: Previous method 2, Green: Previous

method 1, Cyan: Using coherence method

Figure 7: Comparison of the average accuracy rates: Blue:

using 0 or correlation values from multidimensional

directed coherence, Orange: using the correlation values

specified in the relative emotion rules, Green: using all the

correlation values.

6 DISCUSSIONS

Comparing the results of applying all correlation

values from multidimensional directed coherence

analysis to the NN showed that adding noise to the

data improved accuracy for both training and test sets

compared to using noiseless data. This improvement

likely stems from the inclusion of noise-augmented

data in the training set, which enhances learning by

better reproducing regions with significant individual

differences.

Among the four noise types tested, including

white noise with a mean of 0 and variance of 1, no

notable differences were observed in training

accuracy. However, in the test data, pink noise

improved accuracy by approximately 10% compared

to white noise conditions. This suggests that

individual differences are more concentrated in low-

frequency components than distributed across the

frequency spectrum.

In addition to pink and white noise, other colored

noises such as brown, blue, and violet noise were also

evaluated. Their definitions are based on Beran et al.

(2013) and Kasdin and N.J. (1995). When applied,

these noises resulted in lower test accuracies than

white noise.

Blue and violet noise increase power in high-

frequency components, which do not effectively

represent individual differences occurring in lower

frequencies. Brown noise, while similar to pink noise

in emphasizing low-frequency components, exhibits

a steep power decline at higher frequencies, limiting

its ability to retain necessary high-frequency

information. This limitation likely explains why

brown noise did not achieve the same performance as

pink noise.

These findings suggest that low-frequency noise

is critical for reproducing individual differences and

improving test accuracy, while specific high-

frequency components are also necessary. Pink noise,

which satisfies both conditions, is particularly

effective in capturing individual variability.

A comparison between the proposed method and

three conventional methods based on the relative

emotion rule showed that the proposed method

achieved the highest accuracy for both training and test

data. This suggests that incorporating noise during

training not only replicates individual differences but

also highlights subtle, non-statistically distinct features

essential for emotion differentiation.

Additionally, the proposed method was compared

to two other cases: one using only values from the

conditions recorded in the relative emotion rule, and

another assigning a value of 0 when the rule

conditions did not match the test data. The proposed

method, which used all correlation values,

outperformed both, achieving the highest accuracy

for training and test data. This result suggest that

using correlation values enhances the NN's flexibility

during training and enables the extraction of features

that, while not recorded in the relative emotion rule

or statistically distinct, are crucial for accurate

emotion estimation.

Electroencephalograph Based Emotion Estimation Using Multidimensional Directed Coherence and Neural Networks Under Noise

653

7 CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we propose an EEG-based method for

emotion estimation, where EEG data with and

without added noise are processed through

multidimensional directed coherence analysis and

then used to train a NN. Conventional methods have

relied on features with statistically significant

differences among emotions for estimation. In

contrast, our proposed method utilizes all data from

the coherence analysis, allowing the NN to identify

important features for emotion estimation even if

statistical differences between emotions are absent.

By incorporating noise to account for individual

differences, we aimed to capture more generalized

features.

The results show that training with noise-added

data achieved higher accuracy than methods without

noise or those based solely on the relative emotion

rule. Among the four noise types tested, pink noise

yielded the highest accuracy, suggesting its

effectiveness in representing individual differences.

Future work will focus on understanding the

relationship between brain activity and emotion by

analyzing information flow and frequency between

electrodes through NN weight analysis. This will help

identify key features for emotion discrimination, even

in the absence of statistical differences. Additionally,

comparisons with other NN-based methods will be

conducted to further evaluate the effectiveness of the

proposed approach.

REFERENCES

J. W. Papez (1937). A proposed mechanism of emotion.

Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry. 79. 217-224.

doi:/10.1001/archneurpsyc.1937.02260220069003

W. Irwin, R. J. Davidson, M. J. Lowe, B. J. Mock, J. A.

Sorenson, and P. A. Turski (1996). Human amygdala

activation detected with echo-planar functional

magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroreport, 7. 1765–

1769. doi:/10.1097/00001756-199607290-00014

M. S. George, T. A. Ketter, P. I. Parekh, B. Horwitz, P.

Herscovitch, and R. M. Post (1995). Brain activation

during transient sadness and happiness in healthy

women. Am. J. Psychiatr, 152, 341-351.

doi:10.1176/ajp.152.3.341

H. Fischer, C. L. Wright, P. J. Whalen, S. C. Mclnerney, L.

M. Shin, and S. L. Rauch (2003). Brain habituation

during repeated exposure to fearful and neutral faces: a

functional MRI study. Brain Res. Bull. 59. 387-392.

doi:10.1016/s0361-9230(02)00940-1

T. Shimada, T. Fukami, and Y. Saito (2009), Brain

activation in response to face images with backgrounds.

Int. J. Innov. Comput. Inf. Control. 5(3). 589-600.

doi:10.1007/978-3-540-36841-0_640

Soraia M. Alarcão and Manuel J. Fonseca (2019). Emotions

Recognition Using EEG Signals: A Survey. IEEE

Transaztions on Affective Computing. 10(3). July-

September. doi:10.1109/TAFFC.2017.2714671

R. Plutchik and H. Kellerman (1980). EMOTION Theory.

Research. and Experience. 3-33, ACADEMIC PRESS.

https://www.amazon.co.jp/Emotion-Research-

Experience-Robert-Plutchik/dp/0125587015

W.Zheng (2017). Multichannel EEG-Based Emotion

Recognition via Group Sparse Canonical Correlation

Analysis. IEEE Transactions on Cognitive and

Developmental Systems. 9(3). 281-290. doi:10.1109/

TCDS.2016.2587290

M. Li and B.-L. Lu (2009). Emotion classification based on

gamma band EEG. Proc. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng.

Med. Biology Soc.. 1223-1226, Minneapolis.

doi:10.1109/IEMBS.2009.5334139

O. Saha, M.S. Mahmud, S.A. Fattah, M. Saquib (2022).

Automatic Emotion Recognition from Multi-Band EEG

Data Based on a Deep Learning Scheme with Effective

Channel Attention. IEEE Access. doi:10.1109/

ACCESS.2022.3224725

H. Torii, T. Shimada, O. Sakata, and T. Fukami (2023).

Emotion estimation by EEG using multidimensional

directed coherence analysis. Inst. Electron. Inform.

Comm. Eng.. J-106-D(6). 401-408. https://search.ieice.

org/bin/summary.php?id=j106-d_6_401&category=D

&year=2023&lang=2&abst=j

H. Torii, T. Shimada, O. Sakata, and T. Fukami (2024).

Emotion Estimation Using Signal Processing and

Neural Network by EEG. In The International Council

on Electrical Engineering Conference 2024.

Kitakyushu. https://orbit-cs.net/icee2024/detailedprogr

am.pdf

O. Sakata, N. Imanishi, T. Shimada, T. Shiina, and Y. Saito

(1998). Causality analysis of alpha activities by

multidimensional directed coherence. Inst. Electrical

Eng. Jpn C. 118. 1016-1025. doi: 10.1541/ieejeiss198

7.118.7-8_1016

T. Kamitake, H. Harashima, H. Miyakawa and Y. Saito

(1982). Directed Coherence Analysis of Time Series

and Its Application to Biological Signal Processing.

Inst. Electron. Inform. Comm. Eng.. J-65-A(8). 779-786

https://search.ieice.org/bin/summary.php?id=j65-a_8_

779

Beran, J., Y. Feng, S. Ghosh, and R. Kulik (2013). Long-

Memory Processes: Probabilistic Properties and

Statistical Methods. NewYork: Springer. doi:

10.1007/978-3-642-35512-7

Kasdin, N.J. (1995). Discrete Simulation of Colored Noise

and Stochastic Processes and 1/fα Power Law Noise

Generation. Proceedings of the IEEE. 83(5). 802-827.

doi: 10.1109/5.381848

BIOINFORMATICS 2025 - 16th International Conference on Bioinformatics Models, Methods and Algorithms

654