Multiscale Entropy Analysis of Continuous Glucose Monitoring Data:

A Comparative Study of Diabetic and Healthy Populations

Cleber França Carvalho

a

, Thilini Savindya Karunarathna

b

and Zilu Liang

c

Ubiquitous and Personal Computing Lab, Kyoto University of Advanced Science (KUAS), Kyoto, Japan

Keywords: Continuous Glucose Monitoring, Multiscale Entropy, Diabetes, Prediabetes, Approximate Entropy,

Attention Entropy, Dispersion Entropy.

Abstract: The advent of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) has made it possible to measure glucose frequently in

daily life. This availability of glucose time series enables advanced analysis to uncover patterns in glycaemic

dynamics that were previously undetectable with traditional blood-sample-based measurements. One such

analytical method is multiscale entropy (MSE), which assesses the complexity of time series data across

varying time scales. In this study, we performed a comparative analysis of MSE across three cohorts:

individuals with type 1 diabetes (T1D), type 2 diabetes (T2D) and prediabetes (PRED). Our goal was to

identify potential differences in glucose dynamics across these groups. We applied three base entropies,

including approximate entropy (ApEn), attention entropy (AttnEn) and dispersion entropy (DispEn). We

found that AttnEn and DispEn were useful in distinguishing between individuals with diabetes (both T1D and

T2D) and those with prediabetes, whereas ApEn did not show significant discriminative power. Furthermore,

we observed no substantial differences between T1D and T2D in terms of their MSE profiles. These results

suggest that MSE, with appropriate base entropy measures, holds promise as a tool for developing biomarkers

to differentiate between diabetes and prediabetes. Future studies could explore additional base entropy

measures and analysing larger, more diverse datasets.

1 INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic condition

characterized by high glucose levels, which can lead

to several systemic complications, such as

cardiovascular diseases, nephropathy, stroke, and

others (Alam et al., 2014). According to the

International Diabetes Federation, 537 million adults

worldwide were living with diabetes in 2021, and this

number is projected to rise to 783 million by 2045,

which is considered a serious public health problem

(IDF Diabetes Atlas, 2021). Diabetes is commonly

classified into two types: Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) and

Type 2 Diabetes (T2D). T1D is a chronic autoimmune

condition that causes destruction of pancreatic beta-

cells, which are responsible for insulin production.

On the other hand, T2D is caused by insulin

resistance or deficiency in the production of insulin

(Kahn et al., 2006). Another emerging condition

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-3740-4355

b

https://orcid.org/0009-0002-4089-9500

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2328-5016

related to insulin malfunctioning is called prediabetes

(PRED), which can be characterized by high glucose

levels after meals but with normal fasting glucose

levels. It is estimated that there are 541 million people

in the world with this condition.

Since there is still no cure for diabetes, the best way

to manage the disease is to change lifestyle habits and

control blood glucose levels. In recent years,

continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) has become

popular as an effective tool for managing diabetes due

to its affordability and convenience (Battelino et al.,

2019). These sensors are attached to the skin,

continuously measuring interstitial glucose, providing

a view of glucose trends and fluctuations throughout

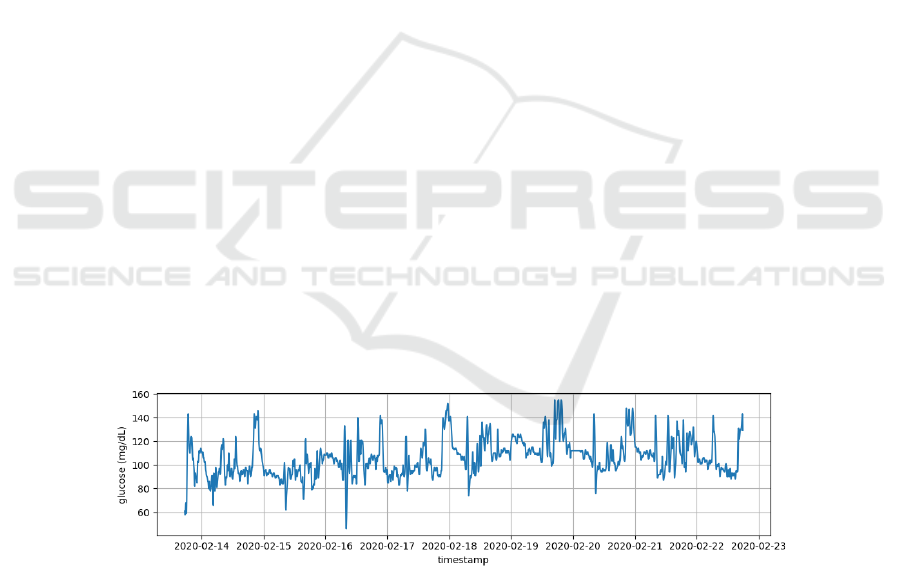

the day and generating a large amount of data (Rice and

Coursin, 2012). These data, as represented in Figure 1,

can be utilized to uncover insights into glycaemic

dynamics and other aspects of human physiology and

behaviour (Bertrand et al., 2021; Liang, 2022).

720

Carvalho, C. F., Karunarathna, T. S. and Liang, Z.

Multiscale Entropy Analysis of Continuous Glucose Monitoring Data: A Comparative Study of Diabetic and Healthy Populations.

DOI: 10.5220/0013257000003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 2: HEALTHINF, pages 720-726

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

CGM data is complex, containing a wealth of

information encoded in the temporal and spatial

patterns of glucose fluctuations. One approach to

characterize this information is through multiscale

entropy (MSE) analysis. MSE is based on the simple

observation that complex human physiological

signals often exhibit dynamics that fall between

perfect regularity and complete randomness. These

signals possess intricate structures that can be

observed at multiple spatial and temporal scales

(Costa et al., 2002). While many studies have

employed MSE to analyse the complexity of glucose

dynamics, most have focused only on a certain type

of entropy measure and usually comparing the

complexity of diabetics to that of healthy individuals.

There is a lack of understanding regarding the

comparative analysis of different entropy measures

across different types of diabetic and prediabetic

populations.

In this work, we analysed CGM time series from

three distinct diabetic populations with MSE, using

different base entropies: approximate entropy

(ApEn), attention entropy (AttnEn) and dispersion

entropy (DispEn). Our goal is to answer the following

research questions: (1) What are the characteristics of

these multiscale entropies of continuous glucose

data? and (2) Which entropy measures are most

effective at differentiating between the three

populations? This study makes two key contributions.

First, it provides new understanding of glycaemic

complexity by employing multiple entropy measures

to analyse glucose signal dynamics. Second, it offers

insights into how different entropy measures can

effectively differentiate between diabetic and

prediabetic populations. These findings have clinical

relevance, as they could lead to the development of

easy-to-measure biomarkers for early diagnosis.

2 RELATED WORKS

Multiscale entropy (MSE) analysis is a powerful

method to assess the complexity and irregularity of

a signal across multiple time scales or levels of a

system. By examining the temporal fluctuations of

the signal, MSE offers insights into the underlying

structure of the information encoded (Bar-Yam,

2004; Nawaz et at., 2024). MSE has been widely

applied to analyse the complexity of physical and

physiological signals, such as heart rate,

electroencephalogram (EEG) and blood oxygen

saturation (SpO2) (Busa et al., 2016; Chu et al.

2021; Chen et al., 2022; Liang, 2023). Regarding

human signals, researchers combined MSE with

Attention Entropy (AttnEn) and applied the method

to SpO2 signals to generate features and in

association with classification machine learning

models to detect sleep apnea (Liang, 2023). Machine

learning models were also used in combination with

MSE and gait force signals to classify

neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s

disease (Nam Nguyen et al., 2020). In the context

of glucose signal analysis, scientists usually apply

MSE and Sample entropy (SampEn). This

combination appears most frequently in the

literature, such when quantifying the complexity of

the temporal structure of the CGM time series in

non-diabetic and diabetic people, with findings

showing that the complexity of the signal is

significantly higher for the non-diabetic subjects

(Costa et al., 2014). In order to investigate

relationship between glucose complexity, glucose

variability and insulin resistance, Crenier et. al.,

applied SampEn and detrended fluctuations analysis

into CGM data. As the main results, they found that

SampEn was inversely correlated with insulin

resistance, body mass index and glucose variability

(Crenier et al., 2016). Another study carried out a

retrospective cross-sectional analysis to evaluate

and compare relationship between indices of non-

linear dynamics and traditional glycaemic

variability, including MSE with SampEn (Kohnert

et al., 2018). Researchers also studied the

comparison between SampEn and Fuzzy Entropy, in

the context of artifact blood glucose time series.

They found that both are sufficient robust to achieve

a significant classification performance (Cuesta-

Frau et al., 2018). Targeting in T2D pregnant

patients under treatment, researchers analysed the

complexity and fractality of glucose dynamics using

MSE and applying SampEn (Chen et al., 2019). Still

with the combination MSE and SampEn, this study

made a comparison of the complexity of CGM

signals between diabetics and control individuals.

They found that the complexity of glucose dynamics

fluctuation decreases in diabetes and MSE

complexity index could be used as a biomarker in

the monitoring of diabetes (Chen et al., 2014). In

other work, scientists applied Approximate Entropy

(ApEn) in glucose readings from T1D subjects, they

found an increase of glucose profile complexity due

to changes of insulin therapies (Lytrivi and Crenier,

2014). Previous studies did not address the use of

different entropies in signal complexity analysis and

considered only a single type of dataset. On the other

hand, this study contributes to the analysis of

different entropies in different datasets with distinct

conditions related to diabetes.

Multiscale Entropy Analysis of Continuous Glucose Monitoring Data: A Comparative Study of Diabetic and Healthy Populations

721

3 METHODOLOGIES

3.1 Datasets

In this study, CGM data from three databases were

retrospectively analyzed. The first dataset included 12

individuals with T1D, 58.3% of whom were women,

with a mean age of 50 years. These individuals were

undergoing treatment with Medtronic Enlite 530G or

630G insulin pumps. No glycated hemoglobin

(HbA1c) data was available for this cohort. Data

collection occurred over 8 weeks, which Medtronic

Enlite CGM sensors recorded blood glucose levels

every 5 minutes (Marling et al., 2020). The second

dataset contains time series blood glucose readings

from 100 individuals with T2D, 44% of whom are

women, with an average age of 60.1 years. These

participants wore FreeStyle Libre sensors for periods

ranging from 3 to 14 days, with glucose readings

automatically recorded every 15 minutes. After

removing duplicate and irregular data, a total of 92

individuals were included in the final analysis and

had an HbA1c average of 75.9 mmol/mol (Zhao et al.,

2023). The last dataset includes data from 16

prediabetic subjects, 56.2% of whom were female,

monitored using the Dexcom G6 device over a 10-day

period. Glucose levels were recorded at 5-minute

intervals, and the cohort's average HbA1c was 41.5

mmol/mol (Goldberger et al., 2000).

3.2 Multiscale Entropy Analysis

The MSE analysis involves a series of iterative steps

for each specified scale factor (τ): a coarse-graining

technique is applied to the signal, followed by the

calculation of the base entropy at each scale.

Regarding the coarse-graining process, the

glucose level signal is segmented into non-

overlapping sequences for different temporal scales.

Given a glucose signal 𝑥

(

𝑖

)

=

{

𝑥

(

1

)

,

𝑥

(

2

)

,…,𝑥

(

𝑁

)

}

,

(

𝑖 = 1,2,…,𝑁

)

, the coarse-grained

signal for scale factor τ

(

τϵℕ

)

represented as:

𝑥

(

𝑗

)

=𝑥

(

1

)

,𝑥

(

2

)

,…,𝑥

(

𝑁/𝜏

)

(1)

Assuming

𝑗=1,2,…,𝑁/𝜏, this signal can be

calculated by the mean of all data points within the j-

th window. When 𝜏=1, 𝑥

(

𝑗

)

is equivalent to the

initial signal. For 𝜏>1 the length of the coarse-

grained signal decreases progressively as the scale

factor τ increases.

The value of 𝜏 is different and depends on the

type of dataset. For the T1D and PRED datasets,

which the glucose recording time is every 5 minutes,

the value of the scale factor is set to values 1 to 12,

corresponding to a time range of 5-60 minutes, which

means that 12 coarse-grained signals were

generated. For the T2D dataset, in which glucose

records are every 15 minutes, 𝜏 values were between

1 and 4, corresponding a time range 15-60 minutes

and generating 4 coarse-grained new signals.

3.3 Base Entropies

Three different entropy measures were utilized:

approximate entropy (ApEn), attention entropy

(AttnEn), and dispersion entropy (DispEn). Unlike

previous studies that typically relied on a single

entropy measure, often sample entropy, our approach

of using three base entropies allows us to capture a

broader range of characteristics in the CGM data.

ApEn has been widely used in various types of

signals, such as physiological and financial data

(Sabeti, 2009). DispEn was selected because it

addresses some limitations of the widely used sample

entropy, particularly in terms of computational cost

and its ability to capture amplitude patterns in signals

(Rostaghi et at., 2016). However, both entropy

measures require parameter tuning, which adds

complexity and uncertainly to analysis. To mitigate

this, we also performed analysis on AttnEn, which

has the advantage of being parameter-free and is

considered robust to variations in time-series length

(Yang, et al. 2020). In what follows we provide a

detailed description of each of these base entropies.

• Approximate Entropy (ApEn)

ApEn is a technique used to quantify the amount of

regularity and the unpredictability of fluctuations

over time-series data (Pincus, 1991). ApEn is

calculated with the following steps:

1. Define parameters: embedding dimension

(𝑚), tolerance threshold for similarity (𝑟).

2. Create 𝑚-dimensional vectors from CGM

time series 𝑥

(

𝑖

)

.

3. For each vector 𝑥

(

𝑖

)

, calculate the distance

between two vectors 𝑥

(

𝑖

)

and 𝑥

(

𝑗

)

as the

maximum absolute difference between their

corresponding components.

4. Define a function

𝐶

(

𝑟

)

that counts the

number of vectors 𝑥

(

𝑗

)

that are similar to 𝑥

(

𝑖

)

,

meaning the distance is less than equal to 𝑟.

5. Calculate Φ

(

𝑟

)

, the average of the

logarithms of 𝐶

(

𝑟

)

.

6. Increase the embedding dimension to 𝑚+1,

repeat the steps 2-5, and calculate Φ

(

𝑟

)

7. The formula of Approximate Entropy is:

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

722

ApEn

(

𝑚,𝑟,𝑁

)

=Φ

(

𝑟

)

−Φ

(

𝑟

)

• Attention Entropy (AttnEn)

AttnEn measures the distribution or spread of attention

across multiple inputs in a system. This method does

not need any parameter to tune, it is robust to the time-

series length and requires only linear time to compute

(Yang et al., 2020). Attention entropy is calculated

with the following four main steps:

1. Identify the peak points 𝑥

(𝑗), which can

be considered as local maxima or a local

minimum.

2. Define the key patterns ω in 𝛺.

3. Calculate the intervals 𝐼

(𝑗) between two

adjacent peak points for each pattern ω for

any given sub-series.

4. Calculate Shannon entropy over

frequencies of all intervals by the equation

below:

AttnEn = −

1

4

𝑝(𝐼

(𝑘))log 𝑝(𝐼

(𝑘))

∈

• Dispersion Entropy (DispEn)

DispEn is a recently introduced entropy metric to

quantify the uncertainty of time series and is fast to

compute (Rostaghi et al., 2016). To calculate DispEn,

the followings steps are necessary:

1. The signal is mapped to c classes, labelled

from 1 to c. The normal cumulative

distribution function (NCDF) is used to map

𝑥

(

𝑗

)

into 𝑦

(

𝑗

)

. Next, the linear algorithm is

used to assign to an integer from 1 to c. For

each member, is converted to 𝑧

,

(

𝑗

)

=

𝑟𝑜𝑢𝑛𝑑(𝑐.𝑦

+0.5).

2. Each embedding vector 𝑧

,,

(

𝑗

)

=

{𝑧

,

(

𝑗

)

,𝑧

,

(

𝑗+𝑑

)

…,𝑧

,

(𝑗 + (𝑚 − 1)𝑑)} ,

with embedding dimension m and time delay

d, is mapped to a dispersion pattern

𝜋

…

(𝑗).

3. For each 𝑐

potential dispersion, relative

frequency is obtained as follows:

p

𝜋

…

(𝑗)

=

𝑁𝑢𝑚𝑏𝑒𝑟{𝑘|𝑘 ≤ 𝑁 −

(

𝑚−1

)

𝑑,𝑧

,,

(

𝑗

)

ℎ𝑎𝑠 𝑡𝑦𝑝𝑒 𝜋

…

(𝑗)}

𝑁 − (𝑚 − 1)𝑑

4. Based on Shannon’s definition of entropy, the

Dispersion Entropy is:

DispEn𝑥

,𝑚,𝑐,𝑑

=−𝑝(

𝜋

𝑣

0

𝑣

1

…𝑣

𝑚−1

𝜏

(𝑗))log 𝑝(𝜋

𝑣

0

𝑣

1

…𝑣

𝑚−1

𝜏

(𝑗))

4 RESULTS

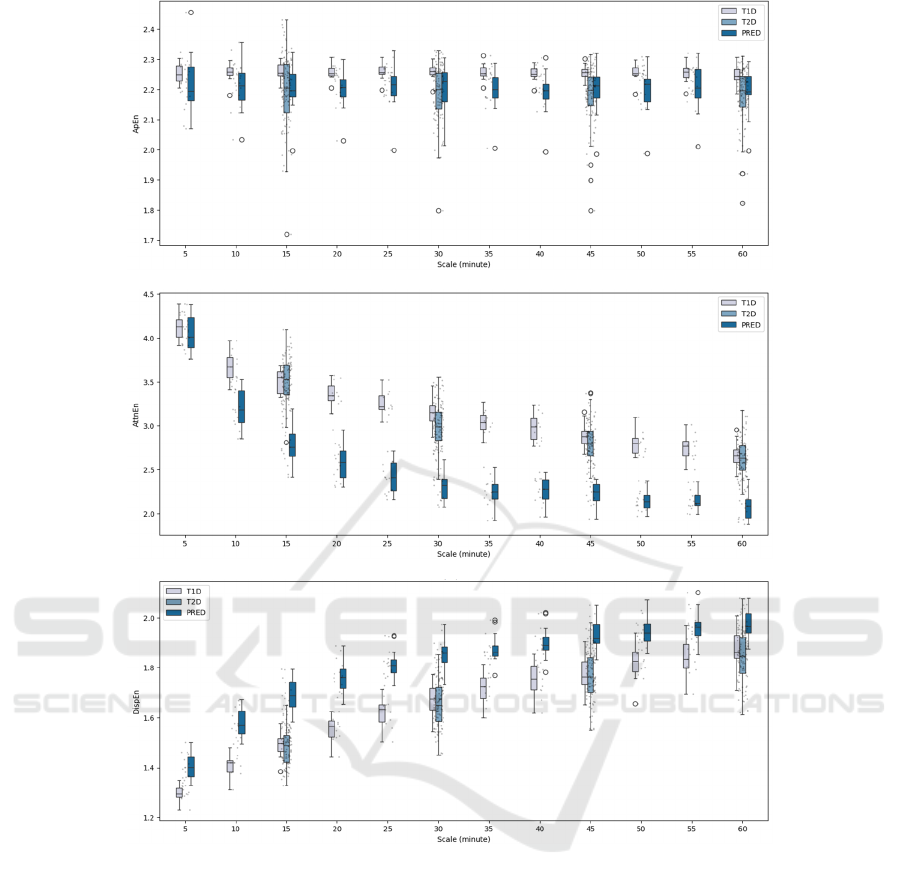

Figure 2 (a) shows the distribution of ApEn across the

time scales. This figure reveals that the entropy values

remain relatively stable, making it difficult to

differentiate between the various diabetic populations

and prediabetes. This suggests that ApEn is not a

useful metric for separating the different populations.

The distribution of AttnEn for three groups at each

time scale is shown in Figure 1 (b). As seen in the

figure, it is noticeable trend of entropy decreasing

over time, which allows for the distinction between

the T1D/T2D and prediabetic datasets from 10

minutes onward, continuing through to the time scale

of 60 minutes. Finally, Figure 1 (c) illustrates the

distribution of DispEn. From this figure, we observe

an increase in entropy values over the time scale, with

a clear separation between the diabetes groups and the

prediabetic group across the entire time scale. This

indicates that DispEn can effectively distinguish

between the CGM data of diabetic patients and

healthy people. Table 1 shows a summary of these

observations.

Table 1: Trends and utilities of three base entropies in MSE

analysis.

Entropy Trend Utility

ApEn Stable Not useful

AttnEn Decrease Useful when time

scale is between

10

–

60 minutes

DispEn Increase Useful

5 DISCUSSIONS

There are few studies related to CGM time series and

entropy analysis (Chen et al., 2019; Lytrivi and

Crenier, 2014). Furthermore, most studies do not

address other types of diabetes incidence, such as

prediabetes and their comparisons among all groups.

This study, we selected three base entropy

measures for analysis. Our analysis revealed that the

three base entropy measures exhibited distinct trends

as the time scale increased, and they showed

differences in their effectiveness at differentiating

between diabetic and the healthy population.

Different patterns among different populations of

diabetic and healthy individuals are expected due to

the characteristic blood glucose level behaviours of

everyone in these groups. Entropy algorithms

manipulate the analysed signal to detect patterns and

Multiscale Entropy Analysis of Continuous Glucose Monitoring Data: A Comparative Study of Diabetic and Healthy Populations

723

characteristics inherent to each analysed population.

We found that approximate entropy was not useful at

any time scale, attention entropy was effective when

the time scale ranged between 10 to 60 minutes, and

dispersion entropy was useful across the entire time

scale analysed. ApEn, despite being widely used in

previous studies on physiological signal analysis, did

not prove useful in distinguishing between the

diabetes and prediabetes cohorts in our study. This

suggests that popular and widely used methods are

not always the most effective for every problem. In

the case of glucose dynamics, ApEn may not capture

the dysfunction in the physiological systems

regulating blood glucose levels in individuals with

diabetes. In contrast, the other two entropy measures,

despite being rarely used in the literature, appear to

provide more relevant insights for our analysis. This

observation underscores the importance of exploring

a diverse range of entropy measures, especially those

that are not yet widely adopted in the literature. It is

also important to note that none of the base entropy

measures were able to differentiate between T1D and

T2D. The possible reasons for this include similarities

in glucose dynamics between T1D and T2D or

limitations in the datasets used.

It is necessary to interpret these results with

caution. The utility of the base entropy measures may

be context dependent. Since our analysis was limited

to three datasets, each homogeneous in terms of

subject demographics, it is important not to

overgeneralize these findings. Further research with

more diverse populations and additional datasets is

necessary to draw more definitive conclusions.

Nonetheless, this research broadens the scope of MSE

analysis applied to glucose signals, and our findings

provide valuable insights that can inspire future

hypotheses and research in this area.

6 CONCLUSION

In this study, we investigated the potential of MSE

analysis to distinguish between individuals with T1D,

T2D, and prediabetes using CGM data. Our findings

highlight the importance of selecting appropriate base

entropy measures. While ApEn, a widely used

measure in physiological signal analysis, proved

ineffective for distinguishing between the diabetes

and prediabetes cohorts, AttnEn and DispEn showed

promising results, especially in capturing dynamic

differences across time scales. In particular, DispEn

was useful across the entire time scale analysed,

suggesting its potential as a more robust marker. In

addition, DispEn entropy analysis showed results

similar to previous studies, in which the complexity

of CGM signals is greater for non-diabetic than for

diabetic subjects and that this technique can detect an

increased regularity in the pattern of glucose

fluctuations (Costa et al, 2014; Chen et al., 2014).

Overall, our work suggests that MSE analysis

holds promise for developing biomarkers to

distinguish between diabetes and prediabetes.

Although no significant differences were observed

between T1D and T2D cohorts, future studies with

larger and more diverse datasets may help clarify the

utility of MSE analysis in differentiating these two

groups. In the next step, we plan to explore additional

entropy measures to deepen our understanding of

glucose dynamics across different populations.

Figure 1: Time-series Continuous Glucose Monitoring.

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

724

(a)

(b)

(c)

Figure 2: Multiscale entropy analysis on CGM data for T1D, T2D, and prediabetes using different base entropy: (a)

Approximate entropy, (b) Attention entropy, (c) Dispersion entropy.

REFERENCES

Alam, U., Asghar, O., Azmi, S., & Malik, R. A. (2014).

General aspects of diabetes mellitus. Handbook of

clinical neurology, 126, 211–222.

Azami, H., Escudero, J. (2018). Amplitude- and

Fluctuation-Based Dispersion Entropy. Entropy;

20(3):210.

Bar-Yam, Y. (2004). Multiscale complexity/entropy. Adv.

Complex Syst, 7, 47–63.

Battelino, T., Danne, T., Bergenstal, RM. et al. (2019).

Clinical targets for continuous glucose monitoring data

interpretation: recommendations from the international

consensus on time in range. Diabetes Care, 42(8):1593-

1603.

Bertrand, L., Cleyet-Marrel, N., Liang, Z. (2021). The Role

of Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Automatic

Detection of Eating Activities.

10.1109/LifeTech52111.2021.9391849.

Busa, M. A., Jones, S. L., Hamill, J., & van Emmerik, R. E.

(2016). Multiscale entropy identifies differences in

complexity in postural control in women with multiple

sclerosis. Gait & posture, 45, 7–11.

Chen, J-L., Chen P-F., Wang H-M (2014). Decreased

complexity of glucose dynamics in diabetes: evidence

from multiscale entropy analysis of continuous glucose

Multiscale Entropy Analysis of Continuous Glucose Monitoring Data: A Comparative Study of Diabetic and Healthy Populations

725

monitoring system data. Am J Physiol Regul Integr

Comp Physiol 307: R179 –R183.

Chen, J.-L.; Shen, H.-S.; Peng, S.-Y.; Wang, H.-M. (2022).

Reduced System Complexity of Heart Rate Dynamics

in Patients with Hyperthyroidism: A Multiscale

Entropy Analysis. Entropy, 24, 258.

Chen, X. et al. (2019). Analyzing Complexity and Fractality

of Glucose Dynamics in a Pregnant Woman with Type

2 Diabetes under Treatment. International journal of

biological sciences. vol. 15,11 2373-2380.

Chu, Y. J., Chang, C. F., Weng, W. C., Fan, P. C., Shieh, J.

S., & Lee, W. T. (2021). Electroencephalography

complexity in infantile spasms and its association with

treatment response. Clinical neurophysiology: official

journal of the International Federation of Clinical

Neurophysiology, 132(2), 480–486.

Costa, M., Henriques, T., Munshi, M. N., Segal, A. R., &

Goldberger, A. L. (2014). Dynamical glucometry: use

of multiscale entropy analysis in diabetes. Chaos

(Woodbury, N.Y.), 24(3), 033139.

Costa, M., Goldberger, A. L., Peng, C. K. (2002).

Multiscale entropy analysis of complex physiologic

time series. Physical review letters, 89(6), 068102.

Crenier, L. et al. (2016). Glucose Complexity Estimates

Insulin Resistance in Either Nondiabetic Individuals or

in Type 1 Diabetes. The Journal of clinical

endocrinology and metabolism vol. 101,4: 1490-7.

Cuesta-Frau, D. et al. (2018). Characterization of Artifact

Influence on the Classification of Glucose Time Series

Using Sample Entropy Statistics. Entropy 20, 871.

Goldberger, A. L., Amaral, L. A., Glass, L., Hausdorff, J.

M., Ivanov, P. C., Mark, R. G., Mietus, J. E., Moody,

G. B., Peng, C. K., & Stanley, H. E. (2000).

PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet:

components of a new research resource for complex

physiologic signals. Circulation, 101(23), E215–E220.

International Diabetes Federation. (2021). IDF Diabetes

Atlas, 10th edn. Brussels, Belgium: International

Diabetes Federation.

Kahn, S. E., Hull, R. L., Utzschneider, K. M. (2006).

Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and

type 2 diabetes. Nature 444, 840–846.

Kohnert, K-D. et al. (2018). Applications of Variability

Analysis Techniques for Continuous Glucose

Monitoring Derived Time Series in Diabetic Patients.

Frontiers in physiology vol. 9 1257.

Liang Z. (2022). Mining associations between glycemic

variability in awake-time and in-sleep among non-

diabetic adults. Frontiers in medical technology, 4,

1026830. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmedt.2022.1026830

Liang, Z. (2023). Novel method combining multiscale

attention entropy of overnight blood oxygen level and

machine learning for easy sleep apnea screening.

Digital Health. 9. 1-19. 10.1177/20552076231211550.

Lytrivi M, Crenier L. (2014). Glucose variability outcome

for type 1 diabetic patients switching to CSII: improved

complexity patterns beyond glucose dispersion

reduction. European Association for the Study of

Diabetes (EASD) 50th Ann Meeting

. Abstract, 1004.

Marling, C., Bunescu, R. (2020). The OhioT1DM Dataset

for Blood Glucose Level Prediction: Update 2020.

CEUR workshop proceedings, 2675, 71–74.

Nam Nguyen, Q.D., Liu, A.-B. & Lin, C.-W. (2021).

Development of a Neurodegenerative Disease Gait

Classification Algorithm Using Multiscale Sample

Entropy and Machine Learning Classifiers. Entropy, 22,

1340.

Nawaz S., Saleem M., Kusmartsev FV., Anjum DH. (2024).

Major Role of Multiscale Entropy Evolution in

Complex Systems and Data Science Entropy 26, no. 4:

330. https://doi.org/10.3390/e26040330

Pincus S. M. (1991). Approximate entropy as a measure of

system complexity. Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences of the United States of

America, 88(6), 2297–2301.

Rice, M. J., Coursin, D. B. (2012). Continuous

measurement of glucose: facts and challenges.

Anesthesiology, 116(1), 199–204.

Rostaghi, M. & Azami, H. (2016). Dispersion Entropy: A

Measure for Time Series Analysis. IEEE Signal

Processing Letters. 23. 1-1.

Sabeti, M. (2009). Entropy and complexity measures for

EEG signal classification of schizophrenic and control

participants. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine. 47 (3):

263–274.

Yang, J., Choudhary, G., Rahardja, S. (2020). Classification

of Interbeat Interval Time-Series Using Attention

Entropy. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing. 1.

10.1109/TAFFC.2020.3031004.

Zhao, Q., Zhu, J., Shen, X., Lin, C., Zhang, Y., Liang, Y.,

Cao, B., Li, J., Liu, X., Rao, W., & Wang, C. (2023).

Chinese diabetes datasets for data-driven machine

learning. Scientific data, 10(1), 35.

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

726