Analysis of Polymers for Additive Manufacturing: Based Contact

Pressure and Force Sensors

Tiziano Fapanni

1 a

, Jacopo Agnelli

2 b

, Raphael Rosa

3 c

, Giuseppe Rosace

3 d

,

Francesco Baldi

2 e

and Nicola Francesco Lopomo

4 f

1

Department of Information Engineering, University of Brescia, Brescia, Italy

2

Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, University of Brescia, Brescia, Italy

3

Department of Engineering and Applied Science, University of Bergamo, Bergamo, Italy

4

Department of Design, Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy

Keywords: Contact Pressure Sensors, Force Sensors, Additive Manufacturing.

Abstract: The rapid advancements in Industry 4.0 and wearable technology have heightened the demand for flexible,

robust, and sensitive sensors that can be integrated into diverse applications. This work investigates the

potential of various polymeric materials, processed through additive manufacturing techniques such as Fused

Deposition Modeling (FDM) and Stereolithography (SLA), to act as transducers in contact pressure and force

sensors. In this work, four possible polymeric materials were tested. Those materials were specifically

selected to present both capacitive and piezoresistive transduction principles, aiming to develop flexible and

highly sensitive sensors to pressure variations. In this frame, one of the key challenges is the hysteretic

behavior typical of polymeric materials, which affects both mechanical (16.9 % on average) and electrical

performance (20.7 % and 24.4% on average on capacitive and resistive devices, respectively). It must be

underlined that significant variations were noted between the filled materials and the microstructured one,

with the latter one being less stiff and able to withstand lower loads (up to 90 N) with an impressive 13-fold

increase in sensitivity compared to thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU). This novel approach seems to pave the

way for optimizable sensor performance in terms of sensitivity at low loads.

1 INTRODUCTION

Following to the Industry 4.0 paradigm, a new

technological era has emerged, thanks to the

integration of different digital tools such as Big Data,

Internet of Things (IoT), Additive Manufacturing

(AM) and Cloud Computing. These technologies

enable a synergistic relationship between humans and

Smart Objects (SOs), a set of interconnected devices

that compose smart systems (Kortuem et al., 2010;

Munirathinam, 2020). SOs are thus devices equipped

with sensors, microcontrollers, and AI-based

algorithms, that can monitor variations in physical

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5164-6907

b

https://orcid.org/0009-0003-8393-2654

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9744-9511

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0604-4453

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6174-4474

f

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5795-2606

parameters (e.g. temperature, humidity, mechanical

deformations, etc.). The real-time collection,

elaboration and transmission of this data allow for the

creation of a digital tread approach that, thanks to

advanced analytics, fosters new functionalities such

as real-time monitoring, automation, and preventive

maintenance in general, thus improving the

possibilities of each device and their production

process as well (Bianchini et al., 2024). The

flexibility of SOs can be seen across a wide range of

industries. For example, in sports, SOs can monitor

athletes’ health, suggest how to improve their

performances, reduce the risk of injuries, and foster

180

Fapanni, T., Agnelli, J., Rosa, R., Rosace, G., Baldi, F. and Lopomo, N. F.

Analysis of Polymers for Additive Manufacturing: Based Contact Pressure and Force Sensors.

DOI: 10.5220/0013257100003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 1, pages 180-187

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

engagement (Mendes et al., 2016). In industrial

settings, SOs provide the possibility to enhance

worker safety, as they can track physiological and

environmental conditions, detecting critical changes

such as temperature/humidity fluctuations or

hazardous pollutants levels (Podgórski et al., 2017);

these insights can help reduce accidents and improve

overall workplace safety and the overall quality of the

product (Borghetti et al., 2021; Saqlain et al., 2019).

In many applications, one of the key parameters to be

monitored is the contact pressure or the exchange

force at the mechanical interfaces, whose measure

requires custom sensors to be developed. These

sensors can detect and measure pressure variations,

which are vital for applications ranging from

wearable devices to robotics. Over the years, a variety

of pressure transducers have been explored, including

piezoresistive, piezoelectric, capacitive, and optical

(Laszczak et al., 2015; Mannsfeld et al., 2010; Pan et

al., 2014; Persano et al., 2013; Ramuz et al., 2012;

Sun et al., 2020). Among these, capacitive pressure

sensors are particularly attractive due to their high

sensitivity, excellent repeatability, low power

consumption, and ability to function independently of

temperature variations (Chortos et al., 2016). On the

other hand, piezoresistive contact pressure sensors are

often easy to produce and use, require low power

consumption, and present a high sensitivity in the

low-pressure range (Gao et al., 2019). Both those

transduction principles can be explored and

developed on flexible and complex geometries using

additive manufacturing (AM). In fact, in recent years,

AM has emerged as a leading technology for

innovative fabrication and prototyping. Two of the

most commonly employed AM techniques are Fused

Deposition Modeling (FDM) and Stereolithography

(SLA). These techniques allow for the creation of

customized, complex geometries using a range of

polymeric materials, making them highly suitable for

the development of flexible and wearable pressure

sensors (José Horst & De Almeida Vieira, 2018). In

particular, FDM is a widely used 3D printing process

that involves the layer-by-layer deposition of

thermoplastic filament, to create a part both in

automotive, aviation and space (Wawryniuk et al.,

2024); this method is particularly useful for

producing robust and flexible components. On the

other hand, stereolithography (SLA) is a high-

resolution additive manufacturing technique that uses

ultraviolet (UV) light to cure photopolymer resins

layer-by-layer (Afridi et al., 2024); this process

allows for the creation of intricate and highly detailed

structures. In the development of contact pressure

sensors, SLA offers precision and flexibility, making

it a suitable choice for creating complex sensor

geometries. Moreover, SLA can be used with various

resins, including flexible materials, which are crucial

for wearable applications. This research aimed to

investigate various additive manufacturing polymers

for the development of contact pressure sensors with

potential applications in wearable devices, industrial

settings, and robotics. By exploring the properties of

different polymers and the advantages of both FDM

and SLA techniques, this work aimed to develop

highly customizable sensors that can adapt to the

specific needs of each application. The sensors

designed in this study are capacitive, meaning they

rely on the ability to measure changes in capacitance

when pressure is applied. In order to achieve resistive

behavior, two materials were selected to explore their

piezo-resistive capabilities. Moreover, a preliminary

microstructured device was fabricated using the SLA

resin to further enhance sensor performance,

particularly at low load levels.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Materials Selection

In this work, a set of different polymers were taken

into account to provide different possibilities for

contact pressure sensors. In order to explore both

resistive and capacitive sensors, both conductive and

dielectric materials were specifically selected.

According to this idea, a flexible resin (SuperFlex

Clear, 3DMaterials, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of

Korea) for stereolithography (SLA) was selected and

mixed with 1% of carbon black (CB) in order to

obtain a resistive material; the CB loading was

limited by its dark color which can block the UV light

properly to properly sinter the resin itself. A second

conductive material is a CB-loaded thermoplastic

elastometer (TPE) provided by ALLOD

(Burgbernheim, Germany) in the form of a slab.

Moreover, a thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU)

filament for fused deposition modelling (FDM)

machines was employed. To further provide devices

with reduced stiffness that can present good

sensitivity at low loads, the SLA mentioned above

resin was used out of the box to produce a set of

microstructured devices; those devices are composed

of a set of unitary cells that can be modeled in 3D as

the combination of four 3D pyramidal structures

(Fapanni et al., 2024).

Analysis of Polymers for Additive Manufacturing: Based Contact Pressure and Force Sensors

181

2.2 Sample Preparation

Each material was prepared in 20 x 20 mm samples

with a thickness ranging from 1.7 mm to 3 mm

according to the different production techniques used.

The samples produced with the superflex resin were

produced using a stereolithographic printer Photon

Mono M5s, by Anycubic. The devices in TPU were

printed with an FDM printer, while the TPE slab was

cut in shape using a laser cutter. Then, in order to

provide easy electrical contact, copper tape was used

to cover the two 20 x 20 mm samples completely.

The tape was then shaped to provide a simple wiring

line with a taper, to avoid sharp edges that could

introduce undesired stray effects.

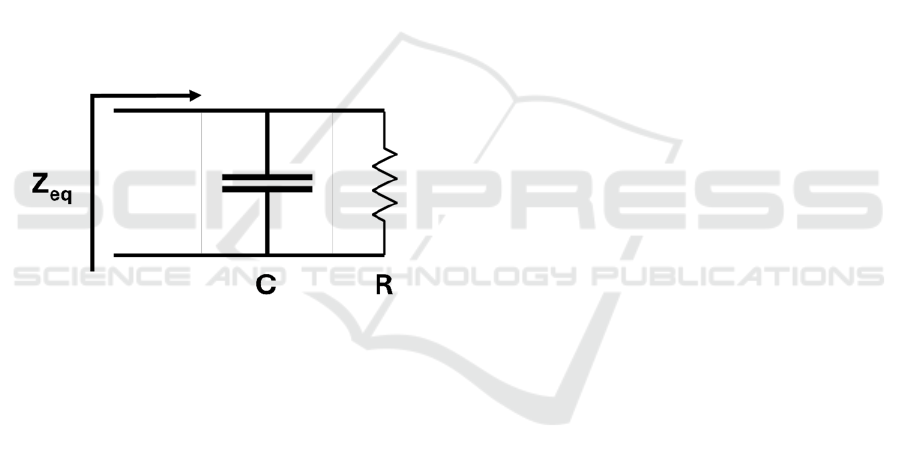

2.3 Sensor Electrical Model

From the electrical point of view, the devices can be

seen as a two-pole composed of a capacitor and a

resistor in parallel as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Electrical reference model for the DUTs.

Considering mainly capacitive devices, it is

possible to consider the capacitance C proportional to

the surface area A of the devices, the relative

permittivity of the insulating layer ɛ

r

and the vacuum

permittivity ɛ

0

, while it is inversely proportional to

the device thickness, d, according to the relationship

C = (ɛ

0

ɛ

r

A)/d

(1)

It is thus possible to modify the capacitance of the

device, by changing either the thickness of the device

(e.g. by applying a load to compress the device) or

changing the relative permittivity of the device due to

the applied load (Fapanni et al., 2024). On the other

hand, for CB-loaded materials, the resistance is

provided by creating an electrical path between the

plates thanks to the conductive CB particles (El

Hasnaoui et al., 2012). When the device is

compressed, the internal disposition of the CB-

particle network is modified, leading to variations in

the resulting resistance (Oh et al., 2022).

2.4 Experimental Setup

In order to characterize the devices as contact

pressure sensors, the experimental setup was

simplified by choosing to monitor the applied load,

which then needs to be converted into pressure by

considering the device surface area. According to

this, an Instron test system (model 3366) equipped

with a 10 kN load cell was used. The uniaxial

compression tests were performed at room

temperature with two planar compression platen with

a 8 cm diameter. A single load-unload cycle was

performed on a representative specimen for each

material. The crosshead speed was set at 0.2 mm/min.

For each material, the maximum load was selected

according to the outcome of preliminary tests. After

those, a single set of analysis were performed on each

material. For each test, the load vs crosshead

displacement curve and the electrical capacitance and

resistance signal were recorded over time. To

measure the relevant electrical components, an MFIA

500 kHz Impedance Analyzer (Zurich Instruments)

was interfaced with a laptop via a custom script. The

device was configured to sample the impedance of the

device at 10 kHz and to provide its equivalent

resistance and capacitance according to the model in

Figure 1.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The mechanical and electrical behavior of the systems

was evaluated by referring to the loading curves (load

vs displacement) and the calibration curves

(capacitance/resistance vs load), respectively. For

both approaches, the hysteresis parameter, calculated

as the ratio between the maximum difference on the

Y-axis between the loading and unloading path, and

the maximum variation on the Y-axis, was

determined. Further, the single-cycle residual

deformation at the very end of the unloading phase

was evaluated. This means that the medium-long time

viscoelastic response of the material was not taken

into account at this stage. Finally, for the electrical

calibration curves, an average sensitivity was

estimated, considering the slope of the second line

through the terminal points.

BIODEVICES 2025 - 18th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

182

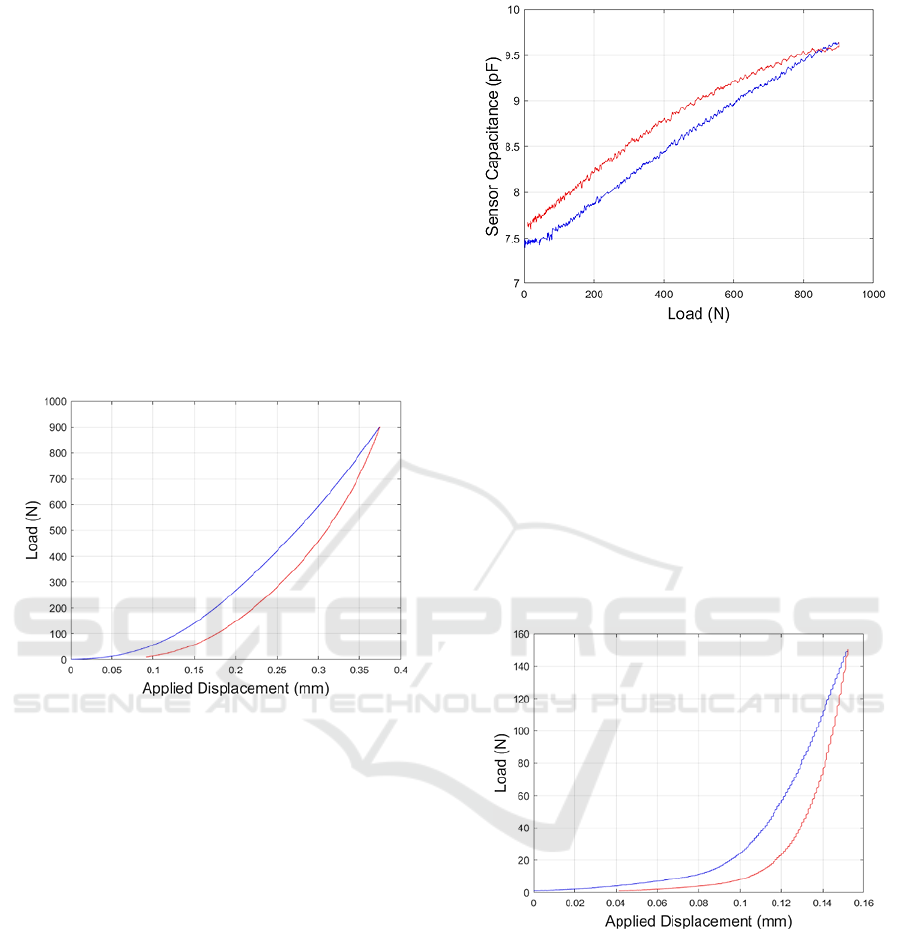

3.1 TPU

This first material that was taken into consideration

(TPU) was designed as purely dielectric solid. Thus,

no piezoresistive effect was expected. Thanks to

previous tests, a maximum load of 900 N was applied.

Considering the load-displacement curve (Figure 2),

the system shows a good linear elastic response, after

an initial transient region caused by imperfect

specimen-plate contact. In this sample, it is possible

to observe a 15.5% hysteresis between the loading

and the unloading path; this phenomenon can be

related to the viscoelastic nature of the material, as

well as to its structure (a set of stacking layers as a

result of the FDM process). The residual deformation

of the system resulted in 5.4 %.

Figure 2: Load – displacement curve of TPU-based sample.

The blue and red graph depict the loading and unloading

respectively.

The capacitance-load curve is shown in Figure 3. It

is possible to observe a general increase of the

capacitance of 26.6% (2 pF), with an average

sensitivity of 2.5 fF/N. A hysteresis value of 17.4%,

mostly related to the mechanical properties of the

dielectric material, was observed. As hinted before, the

resistance variation is irrelevant and presents no

correlation with the applied load (average value > 50

MΩ).

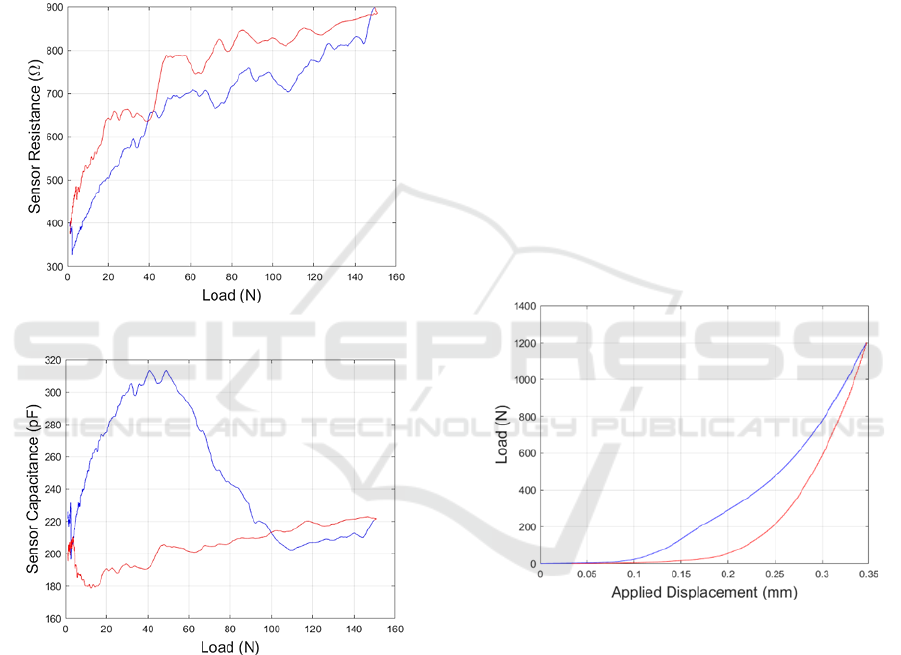

3.2 TPE

A TPE loaded with CB was studied. According to the

conductive behavior of CB, it is possible to achieve a

piezoresistive system since, while applying different

loads, the different conductive primary particles are

arranged so as to generate different conductive paths.

Preliminary analyses on the material pointed out the

presence of the fully-developed linear elastic region

way before reaching 150 N, which was then selected

Figure 3: Capacitance – load curve of TPU-based sample.

The blue and red graph depict the loading and unloading

respectively.

as a threshold value for the tests. A hysteresis value

of 24.5% was observed. However, the increased value

concerning TPU did not result in a corresponding rise

in the residual deformation, which in turn decreased

to 2%. This means that 1) the hysteresis parameter

cannot be considered as an indicator of the dissipative

nature of the system; 2) the TPE is able to recover the

strain imposed better than the TPU immediately.

Figure 4: Load – displacement curve of TPE-based sample.

The blue and red graph depict the loading and unloading

respectively.

In Figure 5, the electrical behavior of the device

at different loads is shown. Considering the resistance

curve (Figure 5a), it is possible to observe its general

and non-linear increase from approximately 300 Ω up

to 900 Ω. In this frame, the device presents an average

3.8 Ω/N sensitivity that can allow only a simple

measurement of the applied load. However, it should

be noted that the behavior of the device is not

perfectly monotone. Thus, further inquiries should be

performed to gain a better understanding of the

Analysis of Polymers for Additive Manufacturing: Based Contact Pressure and Force Sensors

183

response and to determine whether it is related to the

material or the system and the experimental setup. In

these conditions, it is possible to observe a hysteresis

value of 26.1%. The device capacitance curve is

shown in Figure 5b. The response is highly non-

linear, with a non-monotone loading path. Thus, even

if the capacitance ranges approximately between 180

pF and 320 pF, the possibility of developing a

capacitance-based sensor is discarded, as a reliable

calibration line cannot be determined. For instance, it

presents hysteresis at up to 89.8%.

(a)

(b)

Figure 5: Resistance – load (a) and capacitance – load (b)

curves of the TPE-based sample. The blue and red graphs

depict the loading and unloading respectively.

3.3 SLA Resin with CB

The 1-cycle load-unload response of the SLA

superflex resin with CB is shown in Figure 6. The

mechanical response of the system presents some

deviations from the expected trend (see TPU and

TPE, for example), mainly due to the slope change at

around 200N. This is supposed to be related to the

complex nature of the system, characterized by

peculiar internal structuring due to the SLA

technique. A hysteresis value of 21.5% was

determined. The residual deformation at the end of

the smooth unloading phase proved to be 2.1%.

Considering electrical resistance (Figure 7a), it is

possible to observe a high average value over 10 MΩ.

This is related to the low (1%) loading of CB in the

material that the SLA production required. However,

it is possible to identify a satisfying trend that relates

the output resistance to the applied load with an

average sensitivity of -3.2 kΩ/N. It has to be noted

that the noisy nature of the signal could have

influenced the hysteresis value (42.9%). The electric

capacitance (Figure 7b) stays in the range between

12.4 pF to 14.1 pF, with an average sensitivity of 1.4

fF/N. Even though this sensitivity is relevant, it must

be noted that the achieved characteristics presents an

hysteresis value of 38.5% and that a great part of the

capacitance variation is presented at loads of less than

400 N, where the mechanical response is influenced

by system-related effects. According to these

observations the capacitive behavior of such device is

unfit for sensing applications.

Figure 6: Load-displacement curve of the sample produced

by the CB-loaded SLA resin. The blue and red graphs depict

the loading and unloading respectively.

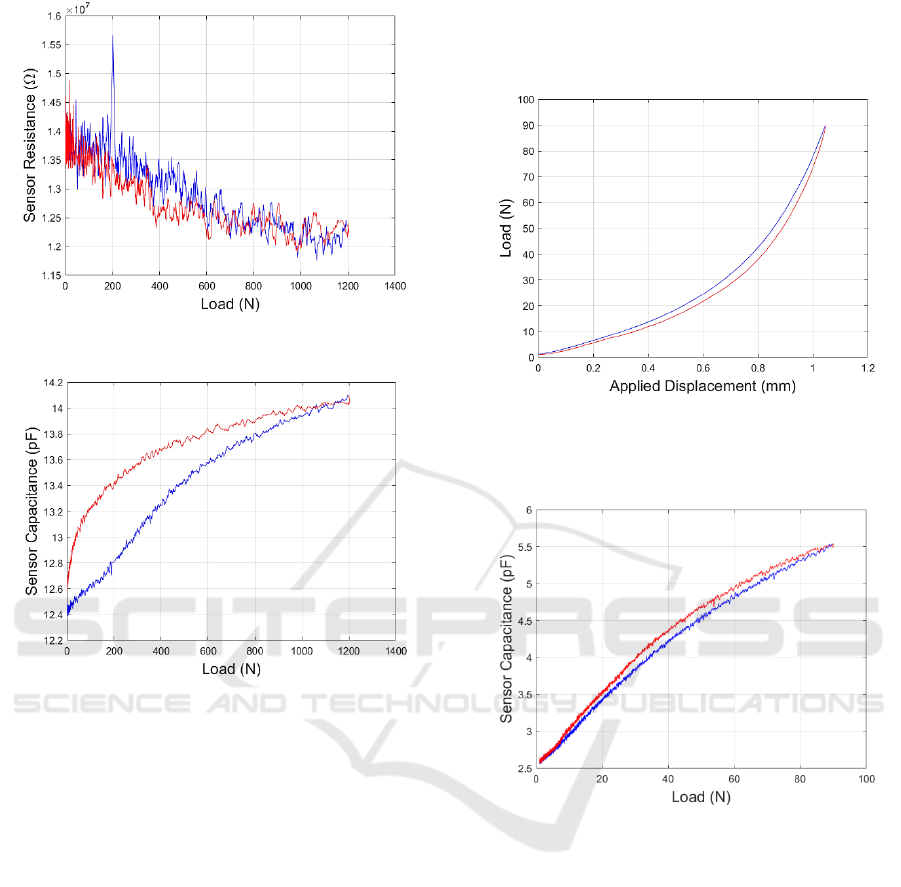

3.4 Microstructured SLA Resin

With the aim to focus on low load values (< 100 N),

specific highly-compliant microstructured resin (the

same type used for CB-loaded systems examined at

3.3), structures, manufactured via the SLA process,

were studied. The mechanical response (Figure 8) is

characterized by a smooth monotonic growth without

any sign of discontinuity during the process. A

maximum load of 90 N was applied, which was

considered suitable from preliminary tests.

BIODEVICES 2025 - 18th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

184

(a)

(b)

Figure 7: Resistance–load (a) and capacitance–load (b)

curves of the sample produced by the CB-loaded SLA resin.

The blue and red graphs depict the loading and unloading

respectively.

Interestingly, while being deformed to higher strains

(at least 3x, concerning the other materials), the

unloading phase is extremely similar to its loading

counterpart, leading to a small 6% hysteresis value.

Further, and even more interestingly, just 0.15% of

residual deformation was observed at the end of the

unloading path, suggesting the possibility for it to be

recovered at short times due to the viscoelastic nature

of the material. This suggests the possibility for this

system to be used in multi-cycle applications (at least

up to 90N). The capacitance (Figure 9) is in the order

of a few nF due to the reduced average relative

dielectric constant produced by the air-resin blend of

the dielectric. On the other hand, thanks to its

flexibility and reduced stiffness, the system is

characterized by a good sensitivity of 33.5 fF/N, with

a reduced hysteresis of 6.2%. Thus, the possibility of

fully recovering the deformation at low times and the

smooth capacitance calibration curve makes the

microstructured SLA resin a promising candidate for

low-load applications.

Figure 8: Load–displacement curve of the microstructured

sample. The blue and red graphs depict the loading and

unloading respectively.

Figure 9: Capacitance–load curve of the microstructured

sample. The blue and red graphs depict the loading and

unloading respectively.

4 CONCLUSIONS

In this work, a set of polymeric bulk and

microstructure materials were tested to inquire about

their capabilities to act as transducers in pressure and

force sensors. Among the possible ones, both

capacitive and piezoresistive transduction principles

were specifically examined. In general, it was

possible to underline a hysteretic behavior on all the

devices; this phenomenon is typical of polymeric

structures and was observed both on the mechanical

and the electrical characteristics. Interestingly, even

Analysis of Polymers for Additive Manufacturing: Based Contact Pressure and Force Sensors

185

though the hysteresis on the capacitance of the

devices has values slightly bigger (20.7% on average)

than the mechanical hysteresis (16.9 % on average),

the hysteresis of the resistance was generallly lower.

However, it is important to notice that between each

material considered, there were wide differences

ranging between the mechanical hysteresis of TPE

(24.5%) to one of the micro-structured devices

(5.9%). Considering the maximum available load, the

filled materials could withstand higher loads of up to

1200 N in general. On the other hand, the micro-

structured one was less stiff and could withstand up

to 90 N, with a stunning 13x increase in sensitivity

concerning TPU. This outcome suggests the

possibility of tuning the device stiffness and its

equivalent relative dielectric constant. Considering

these factors, it may be possible in future works to

produce specific devices with an increased sensitivity

even at low loads. Finally, the full recovery of the

deformation guaranteed by the microstructured

system makes it a promising candidate for multiple-

cycle applications, where this requirement is

mandatory. Even though some of these results are

already reported in the literature, the use of fully 3D

printed structures is still fairly uncommon (Sharma et

al., 2022; Zong et al., 2025). It is also relevant that the

achieved results in terms of sensitivity and working

range seems comparable to the ones reported in the

literature (Li et al., 2024; Zong et al., 2025), even

though further research is needed in order to fully

exploit the capabilities and flexibility of the proposed

approach.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was carried out within the MICS (Made in

Italy – Circular and Sustainable) Extended

Partnership and received funding from the European

Union Next-GenerationEU (PIANO NAZIONALE

DI RIPRESA E RESILIENZA (PNRR) – MISSIONE

4 COMPONENTE 2, INVESTIMENTO 1.3 – D.D.

1551.11-10-2022, PE00000004). This manuscript

reflects only the authors’ views and opinions, neither

the European Union nor the European Commission

can be considered responsible for them.

REFERENCES

Afridi, A., Al Rashid, A., & Koç, M. (2024). Recent

advances in the development of stereolithography-

based additive manufacturing processes: A review of

applications and challenges. Bioprinting, 43, e00360.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bprint.2024.e00360

Bianchini, D., Fapanni, T., Garda, M., Leotta, F., Mecella,

M., Rula, A., & Sardini, E. (2024). Digital Thread for

Smart Products: A Survey on Technologies,

Challenges and Opportunities in Service-Oriented

Supply Chains. IEEE Access.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3454375

Borghetti, M., Cantu, E., Sardini, E., & Serpelloni, M.

(2021). Printed Sensors for Smart Objects in Industry

4.0. 6th International Forum on Research and

Technology for Society and Industry, RTSI 2021 -

Proceedings, 57–62.

https://doi.org/10.1109/RTSI50628.2021.9597209

Chortos, A., Liu, J., & Bao, Z. (2016). Pursuing prosthetic

electronic skin. Nature Materials, 15(9), 937–950.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat4671

El Hasnaoui, M., Triki, A., Graça, M. P. F., Achour, M. E.,

Costa, L. C., & Arous, M. (2012). Electrical

conductivity studies on carbon black loaded ethylene

butylacrylate polymer composites. Journal of Non-

Crystalline Solids, 358(20), 2810–2815.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2012.07.008

Fapanni, T., Rosa, R., Cantù, E., Agazzi, F., Lopomo, N.,

Rosace, G., & Sardini, E. (2024). Overall Additive

Manufacturing of Capacitive Sensors Integrated into

Textiles: A Preliminary Analysis on Contact Pressure

Estimation. Proceedings of the 17th International

Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems

and Technologies, 195–200.

https://doi.org/10.5220/0012597000003657

Gao, L., Zhu, C., Li, L., Zhang, C., Liu, J., Yu, H.-D., &

Huang, W. (2019). All Paper-Based Flexible and

Wearable Piezoresistive Pressure Sensor. ACS Applied

Materials & Interfaces, 11(28), 25034–25042.

https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.9b07465

José Horst, D., & De Almeida Vieira, R. (2018). Additive

Manufacturing at Industry 4.0: a Review. In

International Journal of Engineering and Technical

Research (Issue 8). www.erpublication.org

Kortuem, G., Kawsar, F., Fitton, D., & Sundramoorthy, V.

(2010). Internet of Things Track Smart Objects as

Building Blocks for the Internet of Things.

www.computer.org/internet/

Laszczak, P., Jiang, L., Bader, D. L., Moser, D., & Zahedi,

S. (2015). Development and validation of a 3D-printed

interfacial stress sensor for prosthetic applications.

Medical Engineering & Physics, 37(1), 132–137.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medengphy.2014.10.002

Li, P., Zhang, Y., Li, C., Chen, X., Gou, X., Zhou, Y.,

Yang, J., & Xie, L. (2024). From materials to

structures: a holistic examination of achieving linearity

in flexible pressure sensors. In Nanotechnology (Vol.

36, Issue 4). https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-

6528/ad8750

Mannsfeld, S. C. B., Tee, B. C.-K., Stoltenberg, R. M.,

Chen, C. V. H.-H., Barman, S., Muir, B. V. O.,

Sokolov, A. N., Reese, C., & Bao, Z. (2010). Highly

sensitive flexible pressure sensors with

microstructured rubber dielectric layers. Nature

BIODEVICES 2025 - 18th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

186

Materials, 9(10), 859–864.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat2834

Mendes, J. J. A., Vieira, M. E. M., Pires, M. B., & Stevan,

S. L. (2016). Sensor fusion and smart sensor in sports

and biomedical applications. In Sensors (Switzerland)

(Vol. 16, Issue 10). MDPI AG.

https://doi.org/10.3390/s16101569

Munirathinam, S. (2020). Industry 4.0: Industrial Internet

of Things (IIOT) (pp. 129–164).

https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.adcom.2019.10.010

Oh, J., Kim, D.-Y., Kim, H., Hur, O.-N., & Park, S.-H.

(2022). Comparative Study of Carbon Nanotube

Composites as Capacitive and Piezoresistive Pressure

Sensors under Varying Conditions. Materials, 15(21),

7637. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15217637

Pan, L., Chortos, A., Yu, G., Wang, Y., Isaacson, S., Allen,

R., Shi, Y., Dauskardt, R., & Bao, Z. (2014). An ultra-

sensitive resistive pressure sensor based on hollow-

sphere microstructure induced elasticity in conducting

polymer film. Nature Communications, 5.

https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4002

Persano, L., Dagdeviren, C., Su, Y., Zhang, Y., Girardo,

S., Pisignano, D., Huang, Y., & Rogers, J. A. (2013).

High performance piezoelectric devices based on

aligned arrays of nanofibers of

poly(vinylidenefluoride-co-trifluoroethylene). Nature

Communications, 4.

https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2639

Podgórski, D., Majchrzycka, K., Dąbrowska, A.,

Gralewicz, G., & Okrasa, M. (2017). Towards a

conceptual framework of OSH risk management in

smart working environments based on smart PPE,

ambient intelligence and the Internet of Things

technologies. International Journal of Occupational

Safety and Ergonomics, 23(1), 1–20.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2016.1214431

Ramuz, M., Tee, B. C. K., Tok, J. B. H., & Bao, Z. (2012).

Transparent, optical, pressure-sensitive artificial skin

for large-area stretchable electronics. Advanced

Materials, 24(24), 3223–3227.

https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201200523

Saqlain, M., Piao, M., Shim, Y., & Lee, J. Y. (2019).

Framework of an IoT-based Industrial Data

Management for Smart Manufacturing. Journal of

Sensor and Actuator Networks, 8(2), 25.

https://doi.org/10.3390/jsan8020025

Sharma, A., Ansari, M. Z., & Cho, C. (2022).

Ultrasensitive flexible wearable pressure/strain

sensors: Parameters, materials, mechanisms and

applications. In Sensors and Actuators A: Physical

(Vol. 347). Elsevier B.V.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sna.2022.113934

Sun, L., Jiang, S., Xiao, Y., & Zhang, W. (2020).

Realization of flexible pressure sensor based on

conductive polymer composite via using electrical

impedance tomography. Smart Materials and

Structures, 29(5), 055004.

https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-665X/ab75a3

Wawryniuk, Z., Brancewicz-Steinmetz, E., & Sawicki, J.

(2024). Revolutionizing transportation: an overview of

3D printing in aviation, automotive, and space

industries. The International Journal of Advanced

Manufacturing Technology.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-024-14226-y

Zong, X., Zhang, N., Ma, X., Wang, J., & Zhang, C.

(2025). Polymer-based flexible piezoresistive pressure

sensors based on various micro/nanostructures array.

Composites Part A: Applied Science and

Manufacturing, 190, 108648.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesa.2024.108648

Analysis of Polymers for Additive Manufacturing: Based Contact Pressure and Force Sensors

187