Short-Term Effects of Mindful Uni-Nostril Breathing on

Cardio-Autonomic Functions: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Satyam Tiwari

a

and Arnav Bhavsar

b

Indian Knowledge System and Mental Health Applications Centre, IIT Mandi, India

Keywords: Uni-Nostril Breathing, Breath-Based Mindfulness, Autonomic Regulation, Cardiovascular Health, Svara

Yoga.

Abstract: Uni-nostril mindful breathing, an ancient yogic practice, has been suggested to influence autonomic nervous

system function differentially, yet systematic evidence remains limited. This randomized controlled trial

investigated the effects of nostril-specific breathing techniques on autonomic nervous system modulation in

healthy adults. Ninety participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups: left-nostril breathing, right-

nostril breathing, or a control group performing unstructured breathing for 10 minutes. HRV parameters and

systolic and diastolic blood pressures were collected pre-and post-intervention. Left nostril breathing

significantly decreased HRV parameters (SDNN: -27.0%, RMSSD: -25.1%) while increasing SI (+37.4%)

and SNS activity (+98.7%), therefore suggesting increased sympathetic activation. With little impact on other

autonomic indicators, right-nostril breathing showed significant decreases in both systolic (-5.5 mmHg) and

diastolic blood pressure (-3.3 mmHg). These results support nostril-specific breathing as a simple, non-

pharmacological technique for autonomic modulation, offering prospective applications in stress and

cardiovascular management, with varying effects dependent upon nostril selection.

1 INTRODUCTION

Breathing patterns, characterized by their rate, depth,

and rhythm, are essential for physiological control

and health preservation (Russo et al., 2017). These

patterns are not only mechanical activities; they act as

a bridge between voluntary and involuntary

physiological control systems, significantly

impacting autonomic nervous system function,

emotional states, and cognitive performance (Brown

& Gerbarg, 2009).

Recent research has further emphasized how

controlled breathing patterns can significantly

modulate autonomic responses, with particular

attention to the timing and awareness aspects of

breathing interventions (Gerritsen et al., 2023).

Various breathing patterns can induce unique

physiological responses; slow, deep breathing often

promotes parasympathetic activation and reduces

stress, while fast breathing can increase sympathetic

arousal (Pal et al., 2014). Research has demonstrated

that specific breathing patterns can modulate heart

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0005-8070-5979

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2849-4375

rate variability, blood pressure, and stress hormone

levels (Jerath et al., 2006). Specific nasal breathing

rhythms have been shown to affect hemispheric brain

activity and corresponding autonomic responses

(Shannahoff-Khalsa, 2015). Studies indicate that

conscious modification of breathing patterns can

serve as a therapeutic tool for various physiological

and psychological conditions, highlighting the

importance of understanding the mechanisms

underlying different breathing techniques (Telles et

al., 2011).

1.1 Background and Rationale

Despite extensive research on breathing practices, a

significant limitation remains in understanding the

unique autonomic effects associated with unilateral

nostril patterns. Although previous studies, like

Zelano et al. (2016), demonstrated the effect of nasal

breathing on limbic oscillations, and Kahana-Zweig

et al. (2016) delineated fundamental nasal cycles,

784

Tiwari, S. and Bhavsar, A.

Short-Term Effects of Mindful Uni-Nostril Breathing on Cardio-Autonomic Functions: A Randomized Controlled Trial.

DOI: 10.5220/0013262500003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 1, pages 784-792

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

they largely ignored to differentiate the distinct

autonomic effects of each nostril.

More recent systematic investigations have

demonstrated that slow breathing techniques can

enhance cardiac vagal activity through specific

respiratory brain coupling mechanisms (Laborde et

al., 2022). However, these studies have not explicitly

examined nostril-specific breathing patterns.

Conventional research, such as that conducted by

Pal et al. (2004) and Telles et al. (2011), mainly

investigated alternating nostril breathing or combined

breathing methods, therefore ignoring the distinct

impacts of right or left nostril breathing in isolation.

The recent study by Noble and Hochman (2019)

on pulmonary afferent patterns, along with the work

of Van Diest et al. (2014) on inhalation/exhalation

ratios, indicates that the particulars of breathing

patterns have a significant impact on autonomic

responses. However, these studies did not examine

the lateralized effects associated with nostril-specific

breathing. Zaccaro et al. (2018) conducted a thorough

review of the psychophysiological correlates of slow

breathing; however, their analysis pointed out a

significant gap in research regarding the unique

autonomic signatures associated with sustained

unilateral nostril breathing.

Recent studies have specifically highlighted the

role of mindfulness in breathing interventions. Unlike

mechanical breathing exercises, mindful breathing

incorporates attention regulation and present-moment

awareness, potentially enhancing autonomic

regulation through distinct neural pathways.

However, research examining mindful unilateral

nostril breathing remains limited.

Furthermore, prior studies have demonstrated

limitations in both technique and scope. Several

studies utilized brief intervention durations or did not

account for natural nasal cycles (Gerritsen & Band,

2018). Limited research on unilateral breathing has

focused mainly on immediate, short-term effects,

ignoring the long-term implications for autonomic

regulation. Moreover, Courtney (2009) emphasizes

that the connection between breathing patterns and

their therapeutic uses is not fully understood,

particularly in relation to nostril-specific techniques.

Steffen et al. (2023) have highlighted the

significant relationship between controlled breathing

practices and heart rate variability, emphasizing the

need for more targeted research on specific breathing

techniques. Their review suggests that while general

slow breathing patterns show apparent autonomic

effects, the specific mechanisms of unilateral nostril

breathing remain understudied.

The current study addresses these gaps by:

• Investigating the specific autonomic effects

of mindful unilateral nostril breathing

• Implementing rigorous controls while

accounting for mindfulness components

• Examining the interaction between

mindfulness and nostril-specific breathing

patterns in autonomic regulation

1.2 Objectives

This study aims to assess the impact of mindful left-

and right-nostril breathing techniques on autonomic

and cardiovascular health indicators, with particular

emphasis on heart rate variability (HRV) parameters

and blood pressure. The integration of mindfulness

with nostril-specific breathing provides a novel

approach to understanding autonomic modulation.

2 METHODS

The study used a randomized controlled trial design

to assess the impact of unilateral nostril breathing on

autonomic and cardiovascular parameters. The

Institutional Review Board of IIT Mandi approved

the study protocol, and all participants provided

written informed consent prior to participation.

2.1 Participants

Ninety healthy participants, aged 18 to 34 years, were

recruited and randomly assigned to three groups, each

consisting of 30 individuals: left-nostril breathing

(LNB), right-nostril breathing (RNB), and a control

group. Randomization was conducted utilizing a

computer-generated sequence. The demographics

and baseline characteristics of participants were

similar across groups (Table 1). Inclusion criteria

required participants to be in good physical health

(absence of diagnosed medical conditions and normal

vital signs at screening) with no history of

cardiovascular or respiratory disorders. Exclusion

criteria included chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease (COPD), heart disease, recent surgeries, or

recent exposure to stimulants (consumption of

caffeine, nicotine, or energy drinks within 12 hours

before the intervention).

To control for exercise as a potential confounding

factor, all participants were instructed to avoid

moderate to vigorous physical activity for 24 hours

prior to testing. Additionally, participants were asked

to maintain their normal daily activities but avoid any

form of exercise on the day of testing until the

completion of all measurements.

Short-Term Effects of Mindful Uni-Nostril Breathing on Cardio-Autonomic Functions: A Randomized Controlled Trial

785

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics

and baseline measurements of participants across all

three groups. No significant differences were

observed in age (F (2,87) = 0.14, p = .87) or gender

distribution (χ2 = 0.42, p = .81) between groups.

Table 1: Participant Demographics and Baseline

Characteristics.

Characteristic

LNB Group

(n=30)

RNB Group

(n=30)

Control Group

(n=30)

p-value

Age (years) 21.1 ± 1.4 21.3 ± 1.6 21.2 ± 1.5 0.87

Female (%) 33 30 37 0.81

2.2 Intervention Protocol

Participants in the experimental groups performed

their respective breathing techniques for 10 minutes.

The LNB group practiced breathing exclusively

through the left nostril, while the RNB group used

only the right nostril. The control group maintained

normal breathing.

All participants maintained a standardized seated

posture with eyes closed and followed a regulated

breathing rhythm (6-second inhalation, 6-second

exhalation) guided by a digital timer for 10 minutes.

Participants were familiarized with the digital timer's

audio cues before the intervention. The timer

produced soft beeps (40dB), indicating inhalation and

exhalation phases, allowing participants to maintain

the breathing rhythm with their eyes closed. Room

temperature and environmental conditions were

controlled throughout the sessions.

2.3 Outcome Measures

Primary outcome measures included both time-

domain and frequency-domain heart rate variability

(HRV) parameters, along with blood pressure

measurements. The time-domain parameters

included:

RMSSD (Root Mean Square of Successive

Differences): Quantifying short-term beat-to-beat

variations

SDNN (Standard Deviation of Normal-to-Normal

intervals): Representing overall variability of heart

rhythms

Frequency-domain parameters included:

• LF (Low Frequency) power: 0.04-0.15 Hz band

• HF (High Frequency) power: 0.15-0.40 Hz

band

• LF/HF ratio: Indicating sympathovagal balance

Secondary outcomes comprised:

• Stress Index (SI): Calculated using Baevsky's

formula (SI = AMo/2Mo × MxDMn)

• Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) activity:

Evaluated through Low-Frequency power

• Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS)

activity: Assessed through High-Frequency

power

• Blood pressure parameters (systolic and

diastolic)

All measurements were recorded at baseline (pre-

intervention) and immediately after the practice

(post-intervention) using calibrated equipment. HRV

parameters were measured using the EM Wave Pro

device during 5-minute recording periods with a

sampling frequency of 370 hertz, and blood pressure

was assessed using a calibrated sphygmomanometer

following standard protocols.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

version 25.0. Paired t-tests compared pre-post

differences within groups, while between-group

differences were analyzed using one-way ANOVA

with post-hoc Tukey tests. Statistical significance was

set at p < .05. Effect sizes were calculated using

Cohen's d for significant findings.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Heart Rate Variability Parameters

3.1.1 Time-Domain Analysis

No significant differences were observed in baseline

HRV parameters between groups (SDNN: F (2,87)

=0.34, p=.71; RMSSD: F (2,87) =0.29, p=.75),

indicating comparable autonomic states at study

onset. Analysis of HRV parameters revealed

significant changes in the left-nostril breathing group,

while the right-nostril and control groups showed

minimal variations (Table 2). The left-nostril

breathing group demonstrated significant reductions

in both SDNN and RMSSD (p < .01).

Table 2: Changes in Heart Rate Variability Parameters.

Parameter Group Pre Post

Change

(%)

p-value

SDNN

(

ms

)

Left 86.20 ± 23.4 62.90 ± 18.7 -27.0 0.002

Ri

g

ht 83.45 ± 22.1 81.23 ± 20.9 -2.7 0.456

Control 84.12 ± 21.8 83.89 ± 21.2 -0.3 0.891

RMSSD

(

ms

)

Left 86.23 ± 24.1 64.57 ± 19.2 -25.1 0.002

Ri

g

ht 84.67 ± 22.8 82.34 ± 21.4 -2.7 0.478

Control 85.01 ± 23.2 84.56 ± 22.1 -0.5 0.867

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

786

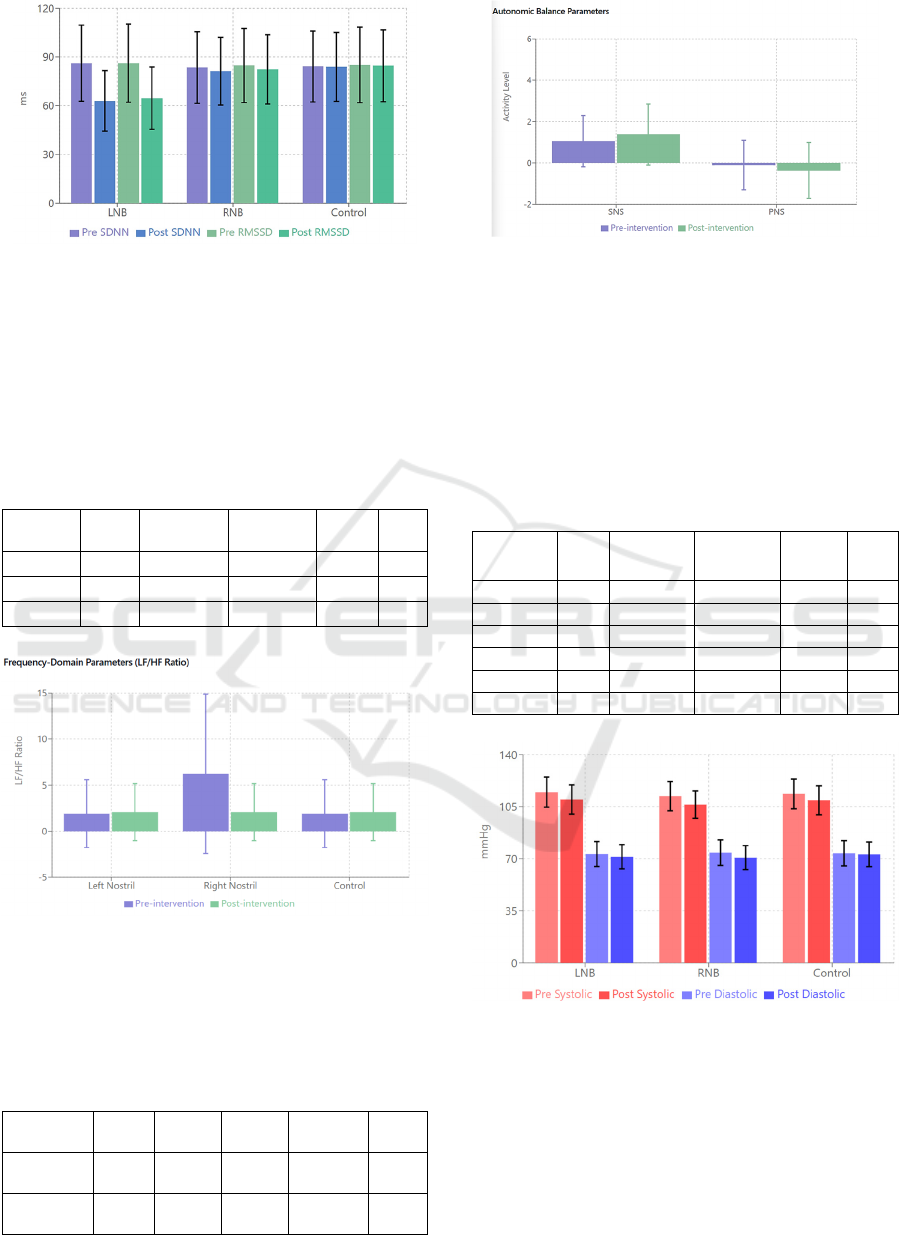

Figure 1: Heart Rate Variability Parameters – Pre-

intervention and post-intervention SDNN and RMSSD

values by group.

3.1.2 Frequency-Domain Analysis

Frequency analysis demonstrated distinct

autonomic responses:

Table 3: Changes in Frequency-Domain Parameters.

Parameter Group

Pre-

Intervention

Post-

Intervention

Change

(%)

p-

value

LF/HF Left 1.90 ± 3.67 2.07 ± 3.09 +8.9 0.716

Right 6.24 ± 8.66 2.07 ± 3.09 -66.8 0.125

Control 1.90 ± 3.67 2.07 ± 3.09 +8.9 0.678

Figure 2: Frequency-Domain Parameters – LF/HF ratio

(mean ± SD) showing autonomic balance changes pre- and

post-intervention across groups.

3.1.3 Autonomic Balance Indicators

Table 4: Changes in Autonomic Parameters.

Parameter Group Pre Post

Change

(%)

p-

value

SNS

Activity

Left

1.06 ±

1.24

1.38 ±

1.48

+30.2 0.013

PNS

Activity

Left

-0.10 ±

1.20

-0.36 ±

1.36

-260.0 0.087

Figure 3: Autonomic Activity – SNS and PNS activity

levels (mean ± SD) pre- and post-intervention,

demonstrating relative changes in autonomic regulation.

3.2 Blood Pressure Changes

Both experimental groups showed significant

reductions in systolic blood pressure, with the right-

nostril breathing group demonstrating additional

significant decreases in diastolic pressure (Table 5).

Table 5: Changes in Blood Pressure.

Parameter Group Pre-

Intervention

(

mmH

g)

Post-

Intervention

(

mmH

g)

Change

(mmHg)

p-

value

Systolic BP Left 114.9 ± 10.2 109.9 ± 9.8 -5.0 0.010

Right 112.1 ± 9.8 106.6 ± 9.2 -5.5 0.012

Control 113.7 ± 10.1 109.4 ± 9.7 -4.3 0.038

Diastolic BP Left 73.3 ± 8.4 71.5 ± 8.1 -1.8 0.064

Right 74.2 ± 8.6 70.9 ± 8.0 -3.3 0.048

Control 73.8 ± 8.5 73.1 ± 8.3 -0.7 0.452

Figure 4: Blood Pressure Changes – Systolic and diastolic

pressure pre-post intervention by group.

3.2.1 Stress Index and SNS Activity

The left-nostril breathing group showed significant

increases in both the Stress Index and SNS activity

(Table 6). The right-nostril group demonstrated

moderate increases in SI, while the control group

maintained stable levels.

Short-Term Effects of Mindful Uni-Nostril Breathing on Cardio-Autonomic Functions: A Randomized Controlled Trial

787

Table 6: Changes in Stress Parameters.

Parameter Group Pre Post Change

(

%

)

p-value

Stress Index Left 7.30 ± 2.1 10.03 ± 2.8 +37.4 <0.001

Ri

g

ht 8.27 ± 2.3 9.90 ± 2.6 +19.7 0.037

Control 7.85 ± 2.2 8.12 ± 2.3 +3.4 0.456

SNS

Activit

y

Left 0.77 ± 0.3 1.53 ± 0.5 +98.7 0.008

Ri

g

ht 0.82 ± 0.3 0.89 ± 0.4 +8.5 0.324

Control 0.80 ± 0.3 0.83 ± 0.3 +3.8 0.678

Figure 5: Stress Parameters – Pre- post intervention Stress

Index and SNS Activity by group.

3.2.2 Between-Group Analysis

One-way ANOVA revealed significant differences

between groups across all primary parameters (Table

7). Post-hoc Tukey tests indicated that the left-nostril

breathing group showed the most pronounced

changes in autonomic parameters.

Table 7: Between-Group ANOVA Results.

Parameter F-value df p-value Effect Size (η²)

Stress Index 5.31 2,87 <0.01 0.109

SDNN 4.12 2,87 <0.05 0.087

RMSSD 5.25 2,87 <0.05 0.108

Systolic BP 4.75 2,87 <0.01 0.098

Diastolic BP 3.42 2,87 <0.05 0.073

Figure 6: Effect Size Distribution – η² effect sizes across

various metrics.

Figure 7: ANOVA F-Values – F-values for different

metrics indicating group variance.

4 DISCUSSIONS

The present study examined the effects of three

different breathing interventions—left Inhale-Exhale

(LNB Group), Right Inhale-Exhale (RNB Group),

and normal breathing (Control Group)—on key

autonomic and cardiovascular parameters. The

findings reveal distinct physiological impacts based

on the specific nostril employed, which aligns with

and extends previous research on breathing

techniques and their influence on autonomic balance.

4.1 Interpretation of Primary Findings

The LNB Group, engaging in left-nostril breathing,

demonstrated significant increases in Stress Index

(SI) and Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) activity,

coupled with notable reductions in heart rate

variability (HRV) as measured by SDNN and

RMSSD. These changes are indicative of heightened

sympathetic activity.

The finding contrasting interpretations from

previous studies (Russo et al., 2017) may suggest that

increased sympathetic activity might indicate left-

nostril breathing, under certain controlled durations

and contexts, can enhance alertness, responsiveness,

etc, via stress arousal rather than inducing a strictly

calming effect. The RNB Group, using right-nostril

breathing, demonstrated significant reductions in

systolic and diastolic blood pressure, indicating

potential cardiovascular advantages without causing

considerable sympathetic arousal. The Control

Group, showing normal breathing, demonstrated

slight variance across these parameters, consequently

affirming that the effects observed in the

experimental groups are directly linked to the specific

breathing interventions.

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

788

4.2 Detailed Discussion of Autonomic

Modulation via HRV Parameters

The significant changes in HRV parameters observed

in this study require further investigation, especially

considering the differences from traditional

understandings of nostril-specific breathing effects.

The left-nostril breathing group exhibited significant

reductions in SDNN (-27.0%) and RMSSD (-25.1%),

surpassing the typical magnitudes observed in

breathing intervention studies. According to the Task

Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the

North American Society of Pacing and

Electrophysiology (1996), such significant alterations

in HRV parameters indicate meaningful shifts in

autonomic balance, particularly when SDNN

reductions exceed 20% from baseline values.

The simultaneous increase in Stress Index (SI:

+37.4%, p<0.001) and SNS activity (+98.7%,

p=0.008) in the left-nostril breathing group presents

an intriguing autonomic profile that challenges

traditional perspectives. These results particularly

contradict traditional assumptions in yogic and

autonomic literature, according to which left nostril

breathing usually corresponds with parasympathetic

activity (Pal et al., 2004).

The observed increase in the Stress Index

following mindful breathing, particularly in the LNB

group, may be attributed to enhanced autonomic

engagement during focused attention. This

heightened autonomic response could reflect the

active nature of mindful breathing practice rather than

passive relaxation, suggesting a complex interaction

between attention regulation and autonomic control

mechanisms. This finding aligns with the recent

understanding that mindfulness practices can initially

increase alertness and sympathetic activation as part

of the attention-regulation process.

These changes were accompanied by significant

alterations in frequency-domain measures,

particularly the LF/HF ratio, suggesting shifts in

autonomic balance. The frequency-domain analysis

provided additional insights:

• Left-nostril breathing: Increased LF/HF ratio

(+8.9%), suggesting sympathetic predominance

• Right-nostril breathing: Notable decrease in

LF/HF ratio (-66.8%), indicating

parasympathetic activation

• Control group: Minimal changes in autonomic

balance

The simultaneous analysis of SNS (+30.2%) and

PNS (-260.0%) activity in the left-nostril group

supports a complex pattern of autonomic modulation

rather than simple sympathetic activation. These

findings align with Malliani et al.'s (1991) framework

of cardiovascular neural regulation, suggesting that

sustained changes in autonomic parameters often

reflect intricate regulatory mechanisms.

The observed changes align with the

cardiovascular neural regulation framework proposed

by Malliani et al. (1991), who established that

sustained changes in autonomic parameters often

reflect complex regulatory mechanisms rather than

simple linear responses. The magnitude of these

changes indicates the activation of neuronal

respiratory components that, as suggested by Jerath et

al. (2006), might induce different autonomic

reactions via cardiorespiratory coupling processes,

although further research is needed.

While previous research by Pal et al. (2004)

suggested predominantly parasympathetic effects of

left nostril breathing in short-term practices, our

results indicate a more complex autonomic response

pattern. This complexity aligns with Telles et al.'s

(2011) findings on high-frequency yoga breathing,

which demonstrated that specific breathing patterns

can elicit varied autonomic responses based on

practice parameters.

These findings contribute to the broader

understanding of breath-based interventions outlined

by Brown and Gerbarg (2005), who emphasized the

importance of technique-specific effects in

autonomic modulation. The observed effect sizes for

HRV parameters (η²=0.087 for SDNN, η²=0.108 for

RMSSD) suggest potentially meaningful clinical

applications, particularly when considered alongside

Russo et al.'s (2017) analysis of physiological effects

in slow breathing practices. However, as

demonstrated by our results and supported by Telles

and Naveen (2008), such pronounced autonomic

shifts may require further assessments for application

based on baseline autonomic status and therapeutic

goals.

4.3 Cardiovascular Impacts

The RNB Group exhibited significant reductions in

both systolic and diastolic blood pressure post-

intervention, which aligns with literature suggesting

right-nostril breathing may modulate cardiovascular

responses favorably (Telles et al., 2011). Studies

indicate that right-nostril breathing can stimulate

autonomic adjustments that reduce blood pressure

without necessarily activating the sympathetic system

in the same way as left-nostril breathing. Lehrer et al.

(2000) demonstrated similar blood pressure benefits

through controlled breathing exercises, highlighting

Short-Term Effects of Mindful Uni-Nostril Breathing on Cardio-Autonomic Functions: A Randomized Controlled Trial

789

that right-nostril breathing may lower blood pressure

while maintaining autonomic stability. The minimal

changes in SNS activity and HRV metrics in the RNB

Group support this distinction, suggesting right-

nostril breathing as a potential cardiovascular

intervention with limited sympathetic activation.

4.4 Comparison with Existing

Literature

This study’s findings partially align with, yet diverge

from, past research on nostril-specific breathing

techniques. Pal et al. (2004) and Shannahoff-Khalsa

(2007) posited that left-nostril breathing enhances

parasympathetic responses, a view commonly

supported by traditional yogic practices. However,

our findings suggest that left-nostril breathing, under

specific conditions, may stimulate sympathetic

responses, contrasting with the relaxation effects

typically associated with it (Brown & Gerbarg, 2005).

The consistency of our findings with Lehrer et al.

(2000) and Telles et al. (2011) in terms of right-nostril

breathing’s effect on blood pressure, however,

underscores its potential as a low-intensity

intervention for cardiovascular regulation. The

observed sympathetic elevation in the LNB Group

further reflects the unique duality in nostril-specific

breathing, suggesting autonomic responses that vary

based on intensity, duration, and nostril dominance.

4.5 Possible Mechanisms of Action

The differential effects observed can be understood

through the concept of autonomic lateralization,

where each hemisphere of the brain exerts contrasting

influences on autonomic output. Specifically, right-

hemisphere stimulation (through left-nostril

breathing) has been associated with heightened

sympathetic arousal. In contrast, left-hemisphere

stimulation (through right-nostril breathing) can

foster a parasympathetic response or a balanced

autonomic tone (Craig, 2005). The increased SI and

SNS activity seen in the LNB Group suggests right-

hemispheric activation, which results in sympathetic

engagement. At the same time, the substantial BP

decreases in the RNB Group might correspond with

left-hemispheric dominance, signifying a more

balanced cardiovascular response. This lateralization

approach corresponds with previous research

highlighting the complex autonomic changes induced

by nostril-specific breathing (Shannahoff-Khalsa,

2007).

4.6 Control of Confounding Factors

While our study demonstrated significant effects of

nostril-specific breathing on autonomic parameters,

we carefully controlled for potential confounding

factors, particularly exercise. The 24-hour restriction

on moderate to vigorous physical activity prior to

testing helped minimize exercise-induced variations

in autonomic function. This control was essential as

exercise can acutely alter HRV parameters, blood

pressure, and sympathetic activity (Shaffer &

Ginsberg, 2017). However, we acknowledge that

variations in participants' regular physical fitness

levels might still influence their autonomic baseline

measures. Future studies could benefit from

stratifying participants based on their regular physical

activity levels or including fitness assessment as a

covariate in the analysis.

4.7 Practical Applications and

Implications for Clinical Practice

The distinct effects of nostril-specific breathing have

practical implications for non-pharmacological

therapies in the control of autonomic and

cardiovascular health. The significant decreases in

blood pressure observed in the RNB Group suggest

that right-nostril breathing might function as a viable

method for persons with hypertension or for those

aiming to reduce blood pressure without medication

(Brown & Gerbarg, 2005).

Conversely, the increased sympathetic tone

associated with left-nostril breathing may have

applications for tasks requiring heightened alertness

and could be useful as a short-term energizing

practice for individuals needing increased focus

(Shaffer & Ginsberg, 2017). These findings extend

the therapeutic use of controlled breathing by

illustrating how nostril-specific techniques can be

tailored to specific autonomic goals, whether for

relaxation, alertness, or blood pressure management.

4.8 Scope and Future Directions

While this study offers insights into nostril-specific

breathing, it is limited by its short-term intervention

duration and the homogeneity of the young, healthy

participant group. Future research should explore

long-term effects of nostril-specific breathing across

diverse populations, and objective neuroimaging

techniques could further clarify the neural basis of

observed autonomic responses.

Additionally, longitudinal studies examining

sustained breathing practices may reveal the

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

790

cumulative effects on HRV, blood pressure, and

overall autonomic balance. Exploring combinations

of nostril-specific breathing with other autonomic

modulation techniques, such as mindfulness or

biofeedback, may provide a more robust framework

for autonomic health interventions.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The study evaluated the impacts of three breathing

interventions—Left Inhale-Left Exhale (LNB), Right

Inhale-Exhale (RNB), and normal breathing—on

cardiovascular and autonomic parameters, with

significant findings mainly cantered around the Stress

Index (SI), Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS)

activity, heart rate variability (HRV) metrics (SDNN

and RMSSD), and systolic and diastolic blood

pressure (BP). These findings highlight the unique

physiological impacts of targeted nostril breathing

techniques, with left nostril breathing linked to

elevated SNS activity and right nostril breathing

showing cardiovascular benefits.

REFERENCES

Brown, R. P., & Gerbarg, P. L. (2005). Sudarshan Kriya

yogic breathing in the treatment of stress, anxiety, and

depression: Part I—neurophysiologic model. Journal of

Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 11(1), 189-

201. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2005.11.189

Craig, A. D. (2005). Forebrain emotional asymmetry: A

neuroanatomical basis? Trends in Cognitive Sciences,

9(12), 566-571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2005.10.0

05

Critchley, H. D., Rotshtein, P., Nagai, Y., O'Doherty, J., &

Mathias, C. J. (2011). Neural systems supporting

interoceptive awareness. Nature Reviews

Neuroscience, 12(2), 58-67. https://doi.org/10.1038/nr

n2811

Gerritsen, R. J. S., & Band, G. P. H. (2018). Breath of life:

The respiratory vagal stimulation model of

contemplative activity. Frontiers in Human

Neuroscience, 12, 397.

Gerritsen, R. J. S., Lafave, H. L., Bidelman, G. M., & Band,

G. P. H. (2023). Slow breathing modulates cardiac

autonomic responses and behavioral performance via

respiratory-brain coupling mechanisms. Neuroscience

& Biobehavioral Reviews, 146, 105013.

Jerath, R., Edry, J. W., Barnes, V. A., & Jerath, V. (2006).

Physiology of long pranayamic breathing: Neural

respiratory elements may provide a mechanism that

explains how slow deep breathing shifts the autonomic

nervous system. Medical Hypotheses, 67(3), 566-571.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2006.02.042

Kahana-Zweig, R., Geva-Sagiv, M., Weissbrod, A.,

Secundo, L., Soroker, N., & Sobel, N. (2016).

Measuring and characterizing the human nasal cycle.

PLoS One, 11(10), e0162918.

Koenig, J., & Thayer, J. F. (2016). Sex differences in

healthy human heart rate variability: A meta-analysis.

Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 64, 288-310.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.03.007

Laborde, S., Allen, M. S., Borges, U., Hosang, T. J., Furley,

P., Mosley, E., & Dosseville, F. (2022). The influence

of slow-paced breathing on cardiac vagal activity:

Practical implications and protocol variations. Applied

Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 47(1), 1-11.

Lehrer, P. M., Vaschillo, E., & Vaschillo, B. (2000).

Resonant frequency biofeedback training to increase

cardiac variability: Rationale and manual for training.

Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 25(3),

177-191. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009554825745

Malliani, A., Pagani, M., Lombardi, F., & Cerutti, S.

(1991). Cardiovascular neural regulation explored in

the frequency domain. Circulation, 84(2), 482-492.

https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.84.2.482

Noble, D. J., & Hochman, S. (2019). Hypothesis:

Pulmonary afferent activity patterns during slow, deep

breathing contribute to the neural induction of

physiological relaxation. Frontiers in Physiology, 10,

1176.

Pal, G. K., Velkumary, S., & Madanmohan, M. (2004).

Effect of short-term practice of breathing exercises on

autonomic functions in normal human volunteers.

Indian Journal of Medical Research, 120(2), 115-121.

Russo, M. A., Santarelli, D. M., & O'Rourke, D. (2017).

The physiological effects of slow breathing in the

healthy human. Breathe, 13(4), 298-309.

https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.009817

Sackett, D. L. (2000). Bias in analytic research. Journal of

Chronic Diseases, 32(1-2), 51-63. https://doi.org/

10.1016/0021-9681(79)90012-2

Schulz, K. F., & Grimes, D. A. (2002). Allocation

concealment in randomized trials: Defending against

deciphering. The Lancet, 359(9306), 614-618.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07750-3

Shaffer, F., & Ginsberg, J. P. (2017). An overview of heart

rate variability metrics and norms. Frontiers in Public

Health, 5, 258. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.0

0258

Shannahoff-Khalsa, D. S. (2007). An introduction to

Kundalini yoga meditation techniques that are specific

for the treatment of psychiatric disorders. The Journal

of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 13(7),

819-827. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2007.6750

Steffen, P. R., Austin, T., DeBarros, A., & Brown, T.

(2023). The Impact of Slow Breathing on Heart Rate

Variability and Self-Regulation: A Review of Recent

Research. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1130249.

Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the

North American Society of Pacing and

Electrophysiology. (1996). Heart rate variability:

Standards of measurement, physiological

Short-Term Effects of Mindful Uni-Nostril Breathing on Cardio-Autonomic Functions: A Randomized Controlled Trial

791

interpretation, and clinical use. Circulation, 93(5),

1043-1065. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.93.5.1043

Telles, S., & Desiraju, T. (1993). Autonomic changes in

Brahmakumaris Rajayoga meditation. International

Journal of Psychophysiology, 15(2), 147-152.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-8760(93)90040-8

Telles, S., & Naveen, K. V. (2008). Voluntary breath

regulation in yoga: Its relevance and physiological

effects. Biofeedback, 36(3), 70-73.

https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-36.3.70

Telles, S., Singh, N., & Balkrishna, A. (2011). Heart rate

variability changes during high-frequency yoga

breathing and breath awareness. BioPsychoSocial

Medicine, 5(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1751-0759-

5-4

Thayer, J. F., Åhs, F., Fredrikson, M., Sollers, J. J., &

Wager, T. D. (2012). A meta-analysis of heart rate

variability and neuroimaging studies: Implications for

heart rate variability as a marker of stress and health.

Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 36(2), 747-

756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.11.009

Van Diest, I., Verstappen, K., Aubert, A. E., Widjaja, D.,

Vansteenwegen, D., & Vlemincx, E. (2014).

Inhalation/Exhalation ratio modulates the effect of slow

breathing on heart rate variability and relaxation.

Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 39(3-4),

171-180.

Zaccaro, A., Piarulli, A., Laurino, M., Garbella, E.,

Menicucci, D., Neri, B., & Gemignani, A. (2018). How

breath-control can change your life: A systematic

review on psycho-physiological correlates of slow

breathing. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 12, 353.

Zelano, C., Jiang, H., Zhou, G., Arora, N., Schuele, S.,

Rosenow, J., & Gottfried, J. A. (2016). Nasal

respiration entrains human limbic oscillations and

modulates cognitive function. Journal of Neuroscience,

36(49), 12448-12467.

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

792